INTRODUCTION

British zoologist Guy Colborn Robson described the Caribbean reef octopus, Octopus briareus, in 1929 (Robson 1929a). Like other cephalopods, this species is capable of changing its color to instantly mimic its surroundings, although its natural coloration is speculated to be a combination of colors between blue and green with brown spots (Snyderman and Wiseman 1996). The species has large prominent eyes, usually surrounded by very dark rings, and very long arms equivalent in length to 5 times that of the mantle (Kaplan 1999). Males and females are similar in appearance, but males have a modified arm (hectocotylus) that is essential for reproduction (Hanlon and Messenger 1996).

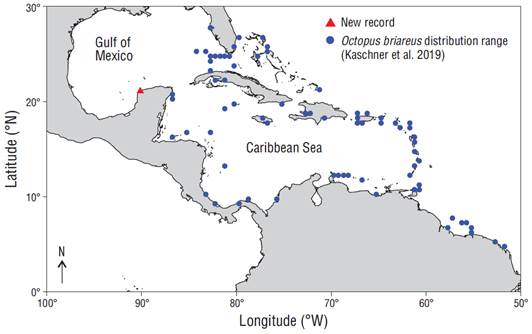

Current knowledge concerning the biological and ecological aspects of O. briareus is very limited, but the spatial distribution of this species is known to extend from southern Florida (USA) and the West Indies (Central America) to the northern coast of South America (Aronson 1986, Cervigón et al. 1992, Jereb et al. 2014, Kaschner et al. 2019) (Fig. 1). It has been suggested that the O. briareus distribution range could include the southern Gulf of Mexico (Robson 1929b, Pickford 1945, Hanlon 1983, Voss et al. 1998), but there is no formal record of the presence of this species there to date.

Figure 1 Octopus briareus distribution (Kaschner et al. 2019) along the Caribbean Sea and the northern coast of South America and location of the new recording off Port Sisal, Yucatan, Mexico.

Since the early 2000s, the Caribbean Basin and the Atlantic Ocean (typical distribution areas for O. briareus) have shown increasing trends in sea surface temperatura (SST) (Nurse and Charlery 2016). Sheppard and Rioja-Nieto (2005) estimated an upward trend in SST for the Caribbean that is consistent with global trends. Jury (2011) described a positive trend for SST off the Antilles, suggesting accelerated warming in recent years, and Lluch-Cota et al. (2013) reported an average increasing trend in the range of 0.05-0.27 ºC per decade for SST in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico and the western Caribbean Sea. Warming trends are likely to affect marine organisms in different ways (migration, gametogenesis, spawning) (Chollett et al. 2012). Changes in the phenology and distribution of marine species, including cephalopods, in response to recent changes in temperature have already been reported in different parts of the world (Philippart et al. 2003, Weishampel et al. 2004, Poloczanska et al. 2016).

Here, we describe the first record of a female Caribbean reef octopus, O. briareus, in the southern Gulf of Mexico (Yucatán Peninsula), formally expanding the species’ known distribution on the American continent. We also discuss the possible cause of the movement of the species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

The Gulf of Mexico (Fig. 1) is a small, semiclosed ocean basin with tropical marine currents that occupies 1.5 million square kilometers (Bryant et al. 1991, Salvador 1991). It is part of the circulation of the Atlantic Ocean channeling the transport of heat, salt, nutrients, and biological material from the Caribbean Sea to the North Atlantic. It also plays an important role in defining the weather and climate of Central America, the United States of America, and the Caribbean Sea (Muller-Karger et al. 2015). Clear and warm surface waters from the Caribbean Sea enter the basin via the Yucatán Current, forming the Loop Current and the rings that derive from it (Candela et al. 2003, Schmitz et al. 2005, Smith et al. 2014). Six bodies of water have been detected in the Gulf of Mexico, four of external origin, stemming from the inherent relationship with the Atlantic Ocean and introduced into the Gulf of Mexico by the Yucatán-Lazo current system (Vidal et al. 1991), and two known as the 18 ºC wáter mass, detected in the northern subtropical region of the Gulf of Mexico, and the common gulf water, detected throughout practically the entire gulf.

Specimen collection

The O. briareus specimen was collected on 8 August, 2019, at 12:20 PM, in a location 14 km out from Port Sisal, Yucatán, Mexico (21º13.263´N, 90º10.045´W) (Fig. 1). The discovery was made by scientific divers performing routine work at underwater facilities located in the area. Following its collection, the organism was transferred alive to the cephalopod culture laboratory in the Unidad Multidisciplinaria de Docencia e Investigación at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, at Sisal, in a termal container with 20 L of seawater. Since there was no oxygenation equipment, and to avoid stressing the animal, the seawater in the container was changed twice during the trip. The octopus was identified following the method proposed by Robson (1929b). The trip to the laboratory was made in a 14-m long boat with two 115-hp outboard motors; approximate trip time is 28 min under optimal navigation conditions.

RESULTS

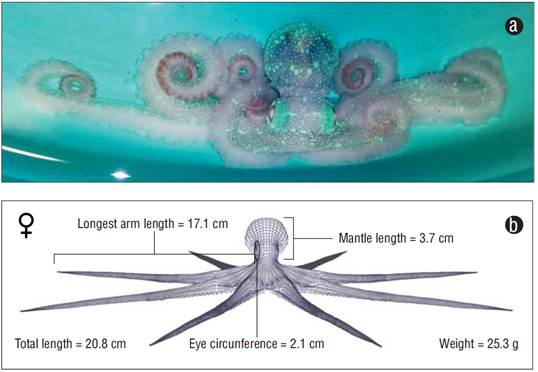

An O. briareus specimen was collected off Port Sisal, Yucatán, Mexico. The organism was an adult female with the following morphometrics: weight = 25.3 g, total length = 20.8 cm, mantle length = 3.7 cm, length of longest arm = 17.1 cm, and eye circumference = 2.1 cm (Fig. 2). The Discovery was made in an area with depth down to 9.7 m, temperatura of 24.0 ºC and visibility up to 12.0 m; the ocean floor in this location was mainly composed of brown algae and medium sand.

Figure 2 (a) Photograph of the Octopus briareus (Robson 1929) specimen captured off Port Sisal, Yucatan, Mexico. (b) Three-dimensional representation and main morphometric characters of the captured specimen.

DISCUSSION

The discovery of this O. briareus specimen is interesting because it suggests that the species could be expanding its westernmost distribution range to areas in the Gulf of Mexico. We could put forward 2 hypotheses. The first is that given the tolerance of O. briareus embryos to high temperaturas (unpublished data) and the climatic changes that have occurred in the area, the species has expanded its distribution because environmental conditions have been favorable. This distribution expansion may have been induced by SST anomalies in the Caribbean, which have been of greater intensity in recent years (Foltz et al. 2018, Varela et al. 2018, Jury 2019). The geographical expansion of various cephalopod species around the world has been documented, with changes in SST being suggested as possible causes (Table 1). Increased SST is also known to be related to coral bleaching and ocean acidification (Nurse and Charlery 2016), and these phenomena could cause massive habitat loss for this and other species. Allcock and Headlam (2018) suggested that even with its wide distribution range, O. briareus could be at risk given the long-term future theoretical threat from global warming. This species, like many other cephalopods, is very sensitive to environmental changes and is thus considered a good indicator of the present oceanographic conditions (Puerta et al. 2015, Zaragoza et al. 2015). The second hypothesis is that the species has always inhabited the area, but given its low abundance, it had never been seen before. A combination of both hypotheses could be that O. briareus abundance is increasing and its distribution is expanding westward into the Gulf of Mexico because environmental conditions could now be favorable.

Table 1 Geographical expansions of cephalopods associated with changes in sea temperature.

| Order | Scientific name | Geographical location of new record |

Possible cause of geographical expansion |

Reference |

| Octopoda | Muusoctopus eureka | 052º853.4′ S, 060º802.2′ W | Temperature increases in

the epipelagic and mesopelagic layers in the southern hemisphere |

Laptikhovsky et al. (2011) |

| Decapoda | Ommastrephes bartramii | 36º0′1″ N, 25º4′15″ E | Association between the

distribution of the species and the circulation of the warm intermediate waters of the Levan- tine Sea. |

Lefkaditou et al. (2011) |

| Octopoda | Octopus hubbsorum | 24º37′ N, 112º07′ W | The species could possess

physiological adaptations that allow it to optimally ex- plore temperate regions. |

Domínguez-Contreras et al. (2013) |

| Decapoda | Thysanoteuthis rhombus | 16.103º N, 95.278º W | Waters with high seasonal

productivity and low temperature, associated with an upwelling zone in eastern Pacific waters off Mexico. |

Alejo-Plata and Urbano-Alonso (2018) |

| Octopoda | Hapalochlaena fasciata | 33º30'34.99" N 126º31'18.98" E | The

temperature increase in the Sea of Japan has contributed to a slow north- ward change in the distribution. |

Kim et al. (2012, 2018) |

Octopus briareus is an organism that does not have larval stages and has accelerated growth rate, early sexual maturation, and a short life cycle (Robaina 1983). Furthermore, given its nocturnal habits, it is probably not a competing species for the Mexican four-eyed octopus, Octopus maya, an endemic species that is homogeneously distributed along the northern and western continental shelf of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico (Gamboa-Álvarez et al. 2015).

In addition to our record, octopi in the genus Tremoctopus, deep-water animals never before sighted by local people, have reportedly been caught recently by multiple artesanal fishermen in the northeastern Yucatán Peninsula. We therefore suggest that cephalopod biodiversity studies be conducted on the coasts of Yucatán and Campeche, Mexico, in order to update the lists of species inhabiting these areas. We also suggest sampling artisanal catches to assess whether these types of captures are incidental or indicate a change in species composition on the continental shelf of the Yucatán Peninsula.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)