Introduction

People using opioids such as heroin, a substance that usually involves intravenous injection, not only face serious health risks, but are one of the most deprived, marginalized, and stigmatized group of people who use drugs (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC], 2018).

To treat these patients, the use of opioid replacement therapies has been recommended as the first-line choice (Bruneau et al., 2018; World Health Organization, 2009), of which methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) has been recognized as one of the most cost-effective interventions in managing dependence (Mattick, Breen, Kimber, & Davoli, 2009).

Since its inception, MMT has been evaluated in terms of pharmacological safety and medical benefits (Joseph, Stancliff, & Langrod, 2000). In this respect, it is known that MMT reduces the morbi-mortality attributable to the use of opioids, the costs derived from the associated crime, and the transmission of infectious-contagious diseases such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and hepatitis C (Harris et al., 2006), thus contributing to improve the social functioning and quality of life of patients (Khalatbari-mohseni et al., 2019; Fernández Miranda, 2005).

MMT has been successfully implemented in various clinical settings (Harris et al., 2006) and typically incorporates some form of psychological intervention designed to promote the rehabilitation and social reintegration of patients (Brands, Blake, & Marsh, 2003). It has been emphasized that the incorporation of such elements for social reintegration should be an integral component of addiction treatment (Verster & Solberg, 2003), in order to address the social precariousness that affects people using drugs in general and intravenous heroin in particular (Solal & Schneider, 1996).

Although it has been documented the process of social reintegration is linked to various factors associated with greater therapeutic adherence, such as patients characteristics, individual needs, expectations, and satisfaction with treatment effects (Singh, Shrestha, & Bhandari, 2014). The aim of this paper is to contribute to the understanding of the process through an emic analysis of the forms of discursive expression whereby patients with heroin dependency problems who participate in an MMT describe and signify their experience.

Method

Study design

Qualitative study of multiple cases, through which we seek to obtain an ideographic understanding of the topic of study based on the experience and meanings given by the participants (Creswell, 2007). We assume a constructionist perspective which presupposes that the way members of a society interpret the reality in which they live contributes decisively to shaping this reality.

This study was conducted in 2012 as part of an evaluation of the Methadone Maintenance and Detoxification Treatment (MMDT) given at a Heroin Treatment Center (HTC) of Centros de Integración Juvenil, in the city of Tijuana.

Participants

Study participants included patients of both sexes who were receiving maintenance treatment with methadone, who were over 18 years old and who agreed to participate in the study.

The sample was integrated by convenience but sufficient to get theoretical saturation.

Sites

The MMDT offered an opioid replacement alternative for people using injected heroin in hospital or outpatient treatment, seeking to reduce the damage associated with use and improve the living conditions of patients. It consisted of three components: 1) detoxification, designed to stop opioid poisoning through safe medication with methadone; 2) maintenance, consisting of stabilization with methadone to prolong abstinence; and 3) rehabilitation, aimed at promoting the reintegration of patients into the family and social environment, for which it incorporated psychotherapeutic interventions focused on preventing relapses and developing social skills, through individual, group and family inter ventions. These activities were voluntary and made available to patients on a regular basis.

Procedure

Interviews were conducted at the HTC treatment facilities, individually, face to face, and audio-recorded. Identification data were recorded, including age, sex, and pseudonyms selected by the respondents. The interview guide was designed to explore the experience of patients in the program, the process of heroin substitution, implications for their health and psychological state, the situation regarding their family and social integration, and the perceived quality of the service. To this end, open questions were formulated: What has your experience of the program been like? What changes have you experienced in the treatment? How have you felt?, and so on. The interviews were conducted by two researchers with field experience, according to general technical guidelines previously agreed upon, with the necessary conditions of silence, privacy, and safety. The interviews lasted between 40 and 60 minutes and were conducted in a single session.

Most were transcribed with a naturalistic approach, with an intermediate level of editing (Farías & Montero, 2005), following the grammatical conventions of Spanish, but with respect for idiosyncratic expressions, phrases, and other characteristics of spoken language. However, one case could only be retrieved through an interview report prepared as a content report. With regards this English version, we could say that even when many idiosyncratic linguistic twists and connotations were lost in translation, it sufficiently reflects the denotative content of the speech.

The “textualization” of the interview segments included in this paper was undertaken with strict adherence to the recovered transcripts, although occasionally, when the content allowed, we took the liberty of incorporating fragments from different moments of the interview or making adjustments to ensure the consistency and congruence of the material or simplify its presentation, eliminating interpolations or excessive repetitions.

Following the review of the transcribed interviews, two cases that failed to offer adequate discursive density were discarded, as a result of which the sample compiled 12 interviews of heroin-dependent patients, 11 men and one woman (Nicté), with the next characteristics (Table 1):

Table 1. Patients characteristics

| Age of drug | Age of heroin | Methadone | Methadone | Lapse in metha- | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | use onset | use onset | Substances used | initial dose | stabilization | done maintenance | |

| Case (pseudonym) | (years) | (years) | (years) | in last 30 days | (mg) | dose (mg) | treatment |

| Ozzy | 22 | * | * | TB, MJ, MTH, HR, | * | * | 1 week |

| Nicté | 28 | 12 | 16 | TB, HR | 40 | 40 | 2 years |

| Águila | 31 | 11 | 20 | ** | 80 | 120 | 6 months |

| Ángel | 33 | * | * | TB | * | * | 6 months |

| Smiley | 33 | 12 | 18 | ** | 110 | 110 | 7 weeks |

| Juan | 36 | 10 | 22 | ** | 80 | 80 | 2 years |

| Johny | 39 | 17 | 26 | TB, MJ, HR | 50 | 50 | 2 months |

| Matus | 41 | 12 | 16 | TB | 60 | 100 | 2 years, 10 months |

| Junior | 42 | 10 | 23 | MJ, MTH, BZ, HR | 130 | 100 | 2 years |

| Memo | 45 | 10 | 19 | MJ, HR | 40 | 40 | 1 year, 6 months |

| Meño | 45 | 12 | 22 | HR | 100 | 100 | 6 months |

| Rogelio | 45 | 15 | 26 | TB | 80 | 90 | 2 years |

Notes:

*(no information avialable),

**(no consumption reported).

TB: tobacco; MJ: marijuana; MTH: metanphetamines; HR: heroin; BZ: benzodiazepines. All participants reported injecting heroin.

Data analysis

The materials were analyzed in two steps, through narrative and thematic analysis methods. First, we selected –on the basis of the criterion of narrative density– an interview segment as an example that would make it possible to establish a first “diagram” of the discursive contents of interest. According to Agamben (2010), an “example” or “paradigm” is a singular element of a class of objects that it, while being subtracted as example, contributes to constitute. When taken as an example, a specific case allows to define, in its singularity, the intelligibility, structure, and conditions of existence of the whole class (Castro, 2012).

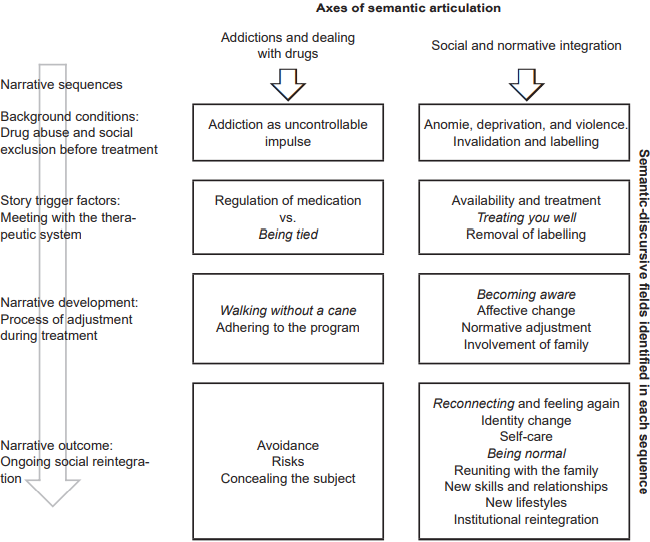

From the analysis of this segment, and according to the logic of real life events depicted in narration (Bal & Van Boheemen, 2009), we identified four clearly differentiated narrative sequences: a) drug abuse and social exclusion before treatment, b) construction of the relationship with the therapeutic system, c) therapeutic process, and d) ongoing social reintegration. We also constructed, through standard coding procedures (Coffey & Atkinson, 2003), a first set of thematic categories, including two dimensions of global semantic articulation, related to how to deal with drugs, and to the expected social reintegration.

Subsequently, as the core phase of analysis, we proceeded, through thematic analysis (Aronson, 1995; Braun & Clarke, 2006; Mieles Barrera, Tonon, & Alvarado Salgado, 2012), to identify patterns of meaning that would provide an understanding of the corpus of study, and would allow us to corroborate, expand, and adjust the initial system, of codes and categories. This led us to a last set of semantic-discursive units, i.e., significant elements that share common spheres of meaning and maintain relationships of implication, causality, contradiction, complementarity, and so on. These discursive units distributed distinctly throughout the four narrative sequences, and according to the two transversal axes of discursive and semantic articulation (Figure 1). A sample of these discursive units is presented in the tables.

Figure 1. Structuring of discursive elements in the narration of the adjustment and social reintegration process by patients participating in a maintenance and detoxification program with methadone.

The joint analysis of materials, the comparison of reviews carried out separately, and a constant discussion of the categories in development enabled us to achieve a reasonable level of “theoretical saturation”, with enough iterations and variations of discursive enunciates within our two main thematic axes. The analysis was performed using a text processor.

Results

Paradigm for reading and first categories system

The following is an excerpt from the interview with Matus, a 41-year-old patient who had a criminal record for attempted murder and possession of weapons used by the army, who had lived for years in poverty, and had been in MMDT for two years, participating in individual and group psychotherapy:

“My experience here has been very good; they have helped me. When I arrived, I was in a r eally bad state ... The first twelve months I spent here I was in a bad state ... because I used methadone, I used pills, I used crystal, in other words, I used a hotchpotch of things. In my individual therapies, even Dr. V. once said to me: Why do you come here? Because I used to fall asleep. She used to tell me: Because you’re just taking up a place ... And there are people who really want to get better. And I think it was the disease itself, I was in a bad state. But she was patient with me, she guided me, she started giving me books ... to read, very good books, she told me: This can motivate you. And, for some reason, she hit the nail on the head.

Then there was Dr. T., who gave me the group sessions, and was also very patient with me. I remember once, I dunno, he said ... I got up very angrily, I was annoyed by something he said, and he calmly replied: No, look, it’s your illness that makes you react like that, and that made me think: Why ... if I’m so rude, do they keep treating me well? And that’s when I started to pay more attention, and I said: There’s no way they can be more worried more about me than I am. They told me things, you know, because... they said: Look, you’re gap toothed ..., and that happened to me because I wasn’t clean, I did not bathe, I was always dirty. I thought they were just saying that to annoy me, but ... I began to understand people’s facial expressions and I saw that they weren’t saying that because of discrimination, they were telling me that because they cared.

So, I started to take time, and... I do not know if it was because they repeated it to me so often... I started to get my teeth fixed and then I began ... And the doctor, who saw I liked to read, said: Why don’t you go to school? I hadn’t finished middle school, I have just completed it ... Now I look cleaner and my family is more respectful to me…”

In this fragment, we can identify elements of a typical narrative structure that links moments or sequences of a process which, beginning with an initial condition, is oriented through a series of episodes and actions as a result of achieving a new state of things. It is a structure of achievement and improvement in which substance abuse is postulated as the initial condition: “When I arrived, I was in a really bad state ... The first twelve months I spent here frankly I was in a bad state... because I used methadone, pills, crystal...,” with a negative connotation: “I used a hotchpotch of things.” This starting point is altered by two factors of change, resulting from the intervention of the therapeutic system, which refer to elements of a clearly normative nature. First, a call to take responsibility: “... Dr. V. once said to me: ‘Why do you come here?’ …. She used to tell me: “Because you’re just taking up a place... And there are people who really want to get out of the disease.” Second, the fact that the interviewee did not receive the discriminatory treatment and rejection he expected: “But she was patient with me, she guided me, and started giving me books,” “Dr. T. was also very patient with me.”

As a result of the “trigger” effect of these two factors, the story takes place through various elements of action:

Becoming aware: “I was in a bad way.”

Giving oneself time: “Then I started to spend time on myself.”

Assuming responsibility: “I started paying more attention to things…”

Becoming aware of the acceptance of the therapeutic team: “There’s no way they can be more worried about me than I am; I began to understand facial features; I understood that they weren’t saying this to me out of discrimination.”

Change of self-image: From: “If I’m so rude” or “I did not bathe,” “I was always dirty,” to: “Now I’m cleaner.”

This set of actions would eventually lead to outcome conditions, related to: a) returning to a school setting: “She said: ‘Why do not you go to school?’ I hadn’t completed middle school; I have just finished it...;” b) self-care: “I began to get my teeth fixed ...;” and a possible change in family relationships: “And my family is more respectful to me …”

This yielded four narrative sequences (background, triggers, narrative action, and outcome) referring to four distinct phases in the treatment and reintegration process:

Background conditions of participation in the MMDT that include an initial state with negative connotations (in the case of Matus, an explicit reference to substance abuse), which is therefore expected to change.

Story trigger factors, which in this case allude to the first and subsequent meetings with the members of the therapeutic system.

Process of adjustment throughout the treatment, comprising a range of actions and measures taken to achieve change.

Social reintegration, which includes, as an outcome, a redefinition of self-image and the relationship with drugs, environment, and agencies of conventional normative society.

Thematic analysis

In the course of the interviews, the four sequences identified do not necessarily unfold in a linear and clearly differentiated way, but may be confused, inverted, repeated, and so on. In any case, they offer a logical framework that allows for the analysis of the remaining cases according to a typical articulation of a dominant social discourse.

Background conditions

The conditions described before participation in the MMDT point in two directions. First, a topic related to addiction, around which an initial semantic and discursive field is formed defining addiction as being related to submission to a compulsive, irrepressible need (Table 2, segments 2.1.1, 2.1.3). It also refers to an idea of an exceeding, overflowing use, with a combination of various “hard” drugs (2.1.5). At the same time, meanings of insensitivity, anesthesia, or lethargy are attributed to it: “Being in a bubble” (2.1.1, 2.1.2, 2.1.4) and a disturbing effect of “nerves” and “cold turkey” (5.2.3 and 5.2.8). It is also associated with images of “getting hooked”, signified as impotence (2.1.4); and of heroin as a “cane” enabling one to walk; of the addict as a “drowsy” subject, “enthralled” by the drug (2.1.3, 2.1.4); and of “reaching rock bottom” as a profound moral and spiritual collapse (2.1.6). Lastly, addiction is linked to relapses, attributed to depression, family and personal problems (2.1.7) and, above all, to the influence of other addicts (5.1.3, 5.1.4).

Table 2. Segments related to conditions prior to treatment

At the same time, it is possible to distinguish, also as an antecedent, social deprivation, including violence and anomie. This involves the prevalence of situations of extreme precariousness and destitution (2.2.1, 2.2.2), discrimination (2.2.3), and violence that goes from the family (2.2.4) to criminal behavior (2.2.5). However, the most frequently observed elements, constituting a central semantic field, refer to invalidation and labeling, with situations such as discredit within the family (2.2.6) and police harassment (2.2.7), whose reiteration affects the internalization of rejection and the production of a profound regulatory gap (2.2.8). Both discursive fields: deprivation and social stigma, share the same sense of exclusion, so they can be assigned to a common thematic axis. Thus, from the same background of treatment, it is possible to infer two axes of thematic articulation which, as will be seen below, are valid in the description of the three remaining phases of the process. The first refers to addiction and dealing with substances; the second, to integration into conventional normative society. Consequently, the analysis of the following phases of the process is carried out considering its link with these two thematic categories, which would therefore operate as transversal axes.

Relationship with the therapeutic system

The second sequence comprises the initial contact with the MMDT and refers to the way the interviewees define the relationship they establish with the therapeutic system.

From the perspective of addiction and substance handling, two opposing discursive fields are formulated. The first involves the question of medication and the pharmacological effects of methadone (“something that touches your brain”), which are given positive connotations and postulate a relationship between taking drugs in regulated doses and obtaining positive results: “being well,” “going out looking clean” (Table 3, segments 3.1.1 to 3.1.5); the second raises the problem of being “tied” to the program (3.1.6) and of developing an addiction to methadone (3.1.7), including the expectation of reducing the dose in order to be “independent” (3.1.8).

Table 3. Segments associated with the relationship with the therapeutic system

With regard to the axis of normative integration, one can also see the formation of two semantic-discursive fields, in this case of a complementary nature. In the first place, there is a description of the availability of the service in terms of “open doors” and “feeling attended” (3.2.1), as well as the characterization of the treatment received in terms of adjectives such as “professional,” “disinterested,” “decent,” “humane,” “kind,” and “respectful” (3.2.2 to 3.2.4). This positive evaluation of the relations established in the therapeutic context intersects with a second domain, of “undoing labeling,” through notions such as “acceptance,” “support,” and “tolerance” that define the attitude adopted by the therapeutic team (3.2.5) and contrast with the previous experience of rejection, thus reversing the fear of being once again subject to stigmatization (3.2.6 and 3.2.7). The effect attributed to undoing labeling is associated with feelings of understanding and trust (3.2.8).

On the other hand, an expectation of guidance was also recorded, expressed explicitly by one of the participants and denoting the establishment of a relationship of dependency on the therapeutic system (3.2.9).

Adjustment process in the treatment environment

Based on the relationship established with the therapeutic system, various issues associated with the actions and measures adopted are displayed, as part of the treatment process, to achieve change.

Regarding the issue of addiction and substance use, the main effects of methadone are cited as being on subjective well-being and adjustment capacity (Table 4, segment 4.1.1), which seem to be attributed, without any mediation, to the effectiveness of the medication alone. However, they are also linked to the need to learn and to develop skills to “be able to walk without a cane” (4.1.2), which could be associated with the expectation of guidance. Other elements include the need to strictly adhere to methadone administration and the benefits of participating in other components of the program: individual psychotherapy and group and family therapy (4.1.3 to 4.1.5). According to the respondents, participating in the program, without restricting themselves to taking the medication, provides the possibility of understanding the meaning of the treatment (4.1.6).

Table 4. Adjustment process in the treatment environment

The effort made in the treatment to achieve the purposes of social reintegration encompasses several other thematic fields or spheres of action. A first action that could be considered a point of support for the development of this sequence is “giving oneself time” or “giving the process” time. This triggers a triple process of cognitive change (“realizing”), affective change (“internal work”) and normative adjustment (which can be summarized as “learning to control oneself”). The field of meanings of “realizing” includes, first of all, becoming aware, the perception of having a problem, and the aim of informing oneself about the process of change (4.2.1) to achieve understanding (4.2.2). and 4.2.3); “understanding” the implications of heroin use, the reasons for beginning to use it, the meaning of treatment, and recognizing the true intentions of the family in encouraging the interviewees to seek treatment, and “things about myself,” affects and fears, “grudges and bad thoughts” (4.2.3).

Affective change includes an effort to undertake internal work (4.2.4) which, following the catharsis, “shogging off many things about myself”, can lead to an affective change primarily identified as the achievement of peace of mind, motivation to change and enhanced self-esteem (4.2.4 to 4.2.6). Likewise, emotional work or that involving “internal complexes” is associated with the modification of attitudes and the building of new skills (4.2.7).

Third, adjustment in the context of treatment implies the possibility of learning to control oneself and to function, presumably within conventional society (4.2.8). It also means reconsidering and assuming responsibility, in a broad sense that implies reciprocity to others, as well as restoring balance, mainly in the family, by adjusting habits and lifestyles, all of which contributes to the possibility of new identity definitions (4.2.9).

In the same way, it expresses the possibility of thinking about the future, which is projected in the expectation of joining the conventional spheres of work and family (4.2.10), which, in some cases, invites them to recover lost values, learned in the family, useful for normative adjustment (4.2.11), or for developing adaptive skills to reverse the effects of exclusion, which show the main role that language and communication skills could have in the process (4.2.12).

Finally, the treatment process also involves the family, both in the sense of bringing it closer to the patient’s problem (4.2.13) and in bringing the latter to new forms of rapprochement (4.2.14).

Social reintegration

This phase points to the outcome of the process. The emphasis is on the conditions of the external environment, which, however, reflect the efforts and attempts to change made within the therapeutic process.

Concerning addiction and dealing with drugs, the main issue is the redefinition of the relationship with them, a field in which respondents specifically raise the issue of avoidance. First of all, they mention avoiding drug abuse networks and areas where drugs are available, which is linked to the search for new friendships and the formation of new support networks within normative society, or confinement in the domestic sphere and social isolation (Table 5, segments 5.1.1 to 5.1.3). This is due to the certainty of the risk of relapse (5.1.4), and the reduction of the risk of contagion (5.1.5). Silence around the issue of drugs in the family is also mentioned. (5.1.6 and 5.1.7).

Table 5. Segments related to the process of social reintegration

Regarding the issue of incorporation into the normative environment, a couple of expressions are proposed as guiding ideas: leading a life like that of “normal” people and taking responsibility, with a clear imperative connotation (5.2.1). However, one of the issues that is consistently identified is coming out of anesthesia, “reconnecting” and “feeling again.” It is not only a question of recovering the ability to enjoy and experience affects (5.2.2) but also of recovering the sensitivity of the body and opening up to the world and others. This experience refers to a new state of well-being (5.2.3) and tranquility (5.2.4). Concomitantly, there is a perception of improvement (5.2.5) that refers to both the ability to reinsert oneself into an institutional setting, and to establish significant interpersonal relationships. All these can be linked to the adoption of positive attitudes (5.2.6) and normative expectations.

Among the factors pointing to change, the respondents cited health care and its effects: “Cleaning up the body,” “Waking up without feeling nervous” (5.2.7, 5.2.8), changing their physical appearance and body image (5.2.9, 5.2.10), as well as changing their habits and lifestyles (5.2.11). At the same time, there is a recognition of a change in attitudes among people around (5.2.12, 5.2.13) which in some way, lends continuity, in the external environment, to the undoing of labels. The perception of this change (“being seen differently”) reinforces feelings of acceptance, validation, and support. Finally, there is a development or recovery of social and communication skills, which permits rapprochement with representatives of the dominant society. It also involves the basic interaction skills required to chat up a girl (5.2.14), take part in a job interview, or engage in conversation with people regarded as being from a higher class.

With regards the social spaces in which the reintegration process takes place, the first thing is the importance given to the family, with which a re-encounter takes place, allowing the re-establishment of acceptance, trust, and mutual care (5.2.15 to 5.2.17). The work sphere also plays an important role in the process of the “normalization” and development of regulatory mechanisms (5.2.18 to 5.2.20), as does going back to school and joining religious groups.

Discussion and conclusion

The analysis undertaken reveals the predominance of narratives with a typical structure that coincide with those identified some time ago by structural analysis (Barthes et al., 1972) and sociology (Labov, 1972). This narrative structure makes it possible to give a pattern, shape, and meaning to the experience of normative adjustment, tracing an upward trajectory characteristic of a progressive narrative of achievement and improvement (Gergen, 2007), with a strong psychosocial content.

Accordingly, this paper allows an approach to “emic” elements of experience (Albertín Carbó, 2000) that yields thematic spheres referring to a process of social and normative adjustment. Without being exhaustive, we can highlight the following:

The problem of drug use and the relationship with substances. Despite being in a process of reconfiguration, this issue is not necessarily resolved, leading to avoidance and concealment strategies with a high psychosocial cost. These aspects have been highlighted by López Torrecillas, Peralta, Muñoz Rivas, and Godoy (2003) and Rodríguez Kuri, Córdova Alcaráz, and Fernández Cáceres (2015).

The social rejection, outcasting, and precariousness, which place the heroin addict in a particular condition of vulnerability. Regardless of whether social exclusion is considered an antecedent or a consequence of drug consumption, it involves a complex combination of interrelated problems such as unemployment, low economic income, loss of skills, the erosion of support networks, exposure to violence, and the breaking of balance in family and other institutions (March, Oviedo-Joekes, & Romero, 2006; Epele, 2010). In Mexico, Fleiz and collaborators have documented factors of this nature associated with exclusion (Fleiz et al., 2019). Disaffiliation and social exclusion combine the effects of psychosocial deprivation, invalidation and rupture of primary integration networks, which lead to the loss of a socially recognized place (Castel, 1997).

The experience of undoing labeling and gaining acceptance and recognition, to which, according to the testimonials of the respondents, we must grant a central place at the beginning of the treatment and process of change. It implies putting the incidence of relational and interpersonal factors in first place, in accordance with Rubio Arribas (2001) and Pascual Mollá and Pascual Pastor, (2017).

The importance given to the experience of “reconnecting” and “feeling again” which, from a subjective perspective, allows to attribute meaning to the reestablishment of a place in the world, enabling the subject to aspire to recognize himself as a human being with full rights, with the capacity for self-observation, becoming closer to others, and having agency over reality (Krause et al., 2006).

Self-care and the development of “lifestyles” and skills for interaction as a twofold strategy of normative adjustment within the dominant framework of normality, including, in particular, linguistic and communication skills for interaction with representatives of the conventional society. That is to say, work with and on oneself, which has been considered the foundation of the ethical subject (Foucault, 1984).

The naturalization of a stereotyped representation of the family and of the means of adjustment (incorporation into educational, work, or religious institutions), which reflects the dominance of relatively rigid conventional adaptation imperatives (Rodríguez-Kuri & Fernández Cáceres, 2014; Osuna Díaz, 2013).

Based on these findings, we can emphasize the advisability of making the treatment approach more flexible, in order to accompany and reinforce the reintegration process without providing scope for the reproduction, from the therapeutic system, of new forms of dependence or abuse (Albertín Carbó, 2000). Our study shows the importance of incorporating psychotherapeutic components that offer integral adjustment alternatives and encourage the broad participation of patients.

Within the therapeutic context, it is worth mentioning the suitability of alternative approaches aimed at the person and not exclusively focused on the addictive process (Brands, Blake, & Marsh, 2003), adapted to the particular needs of each patient, strengthening the socially validated effect of acceptance and recognition that seems to be a central aspect of the patients’ experience.

It is also advisable to develop care strategies that permit closer links between the therapeutic system and the environment, in order to more effectively remove the mechanisms of exclusion and stigma that usually continue operating, as well as to reverse the “deviant” affiliation of those affected (Singh et al., 2014; Verster et al., 2003).

It is also possible to recommend the development of follow-up or accompaniment strategies that will enable the process of change in the external environment to continue, in order to address the relationship between exclusion and relapse conditions. In this respect, it should be noted that the lack of knowledge of both the relational dimensions of reintegration and the suffering associated with exclusion can play a decisive role in the persistence of substance use (Harris et al., 2006; March et al., 2006; Verster et al., 2003).

It is also possible to implement harm reduction programs that imply a different perception of the patient and their needs, such as safe injection rooms, the provision of naltrexone or naloxone to cope with an overdose crisis, and the distribution of methadone for external administration (Priest et al., 2019; Brands et al., 2003; Gutwinski et al., 2013).

Moreover, the implementation of programs must be based on the development of public policies that not only consider the problem of poverty and social and economic precariousness (Verster et al., 2003), including aspects such as access to employment, housing, and dignified salary, but also aspects such as the response of structures in normative society to addicts’ attempts at reintegration.

From a methodological point of view, all of the above results point to the advisability of using indicators sensitive to the various components of the reintegration process in the evaluation of programs, beyond a purely functionalist vision focused on aspects such as obtaining employment or a reduction of antisocial behavior (March et al., 2006).

To conclude, we point out some limitations of this paper. As any exercise of elucidation of the meaning of experience, the one carried out in this work does not constitute but a set of conjectural hypotheses of a material that, from other angles and at other moments, could undoubtedly offer other reading perspectives. Limitations also include those of a qualitative design, which limits the generalization of findings or refers to the specific characteristics of the population segment from which the sample was drawn. One aspect that warrants further exploration, for instance, is the conditions of acute disaffiliation and exclusion that are likely to affect social groups such as women addicts, HIV patients, migrants, and ex-convicts (Joseph et al., 2000; UNODC, 2018).

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)