Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Salud mental

versión impresa ISSN 0185-3325

Salud Ment vol.36 no.2 México mar./abr. 2013

Artículo original

Psychophysiological consequences arising from the stress of everyday life and work activities

Consecuencias psicofisiológicas derivadas del estrés de las actividades cotidianas de la vida y el trabajo

Vaneila Ferreira Martins,1 Vania Moraes Ferreira,1 Dirce Guilhem1

1 School of Health Sciences, University of Brasilia (UnB), Brazil.

Corresponce:

Vaneila Ferreira Martins, MSc.

Universidade de Brasília (UnB).

Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde,

Campus Universitario Darcy Ribeiro

(Asa Norte) 70910-900 Brasília, DF, Brazil.

Phone: (+55-62) 8134-8755.

E-mail: vmmf@yahoo.com

First version: May 21, 2012.

Accepted: December 18, 2012.

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Stress is a common phenomenon among nursing professionals and has received special attention, particularly in relation to the lifestyle characteristic of the contemporary world, which promotes various diseases due to an organic imbalance.

Objective and method

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the psychophysiological consequences of activities in the workplace and everyday life in 408 nursing professionals and to identify ways to improve personal and occupational well-being. A quantitative-qualitative, descriptive and exploratory population-based study was performed.

Results

The results showed that the majority of the sample worked double shifts and viewed themselves as "sometimes stressed". A significant proportion of the professionals experienced verified illnesses, including many chronic-degenerative diseases and neuropathies. Pharmacotherapy was the main treatment used to alleviate the psychophysiological problems and most professionals never used alternative therapies (e.g., psychotherapy) as a way to reduce their stress.

Conclusions

The results suggest that the professionals studied demonstrated psychophysiological alterations resulting from stressors that arise in the workplace and in everyday life. The response to these stressors, although it was frequently not perceived, culminates in several chronic diseases. To cope with these stressful events, individuals must increase their self-esteem and cultivate a more harmonious and balanced work and personal life.

Key words: Behaviour, health care, nursing, professional practice, quality of life, physiological stress.

RESUMEN

Introducción

El estrés es un fenómeno común entre los profesionales de enfermería. Ha recibido especial atención, especialmente en lo que se relaciona con las características del estilo de vida del mundo contemporáneo, que pueden generar distintas enfermedades resultantes del desequilibrio orgánico.

Objetivo y método

El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar las consecuencias psicofisiológicas de las actividades realizadas en el lugar de trabajo y en la vida cotidiana. Fueron entrevistados 408 profesionales de enfermería para identificar posibilidades de promover el bienestar personal y ocupacional. Fue realizado un estudio cualitativo-cuantitativo, descriptivo y exploratorio de base poblacional.

Resultados

Los resultados demostraron que la mayoría de los entrevistados tenían doble jornada de trabajo y se consideraban "algunas veces estresados." Una proporción significativa de los profesionales desarrolló enfermedades, incluidas algunas enfermedades crónico-degenerativas y neuropatías. El tratamiento medicamentoso fue la principal alternativa para aliviar los problemas psicofisiológicos. La mayoría de los profesionales jamás hicieron uso de terapias alternativas (por ej., la psicoterapia) como estrategia para reducir su tensión.

Conclusiones

Los resultados sugieren que los profesionales entrevistados desarrollarán alteraciones psicofisiológicas resultantes del estrés proveniente del lugar de trabajo y de la vida cotidiana. Para hacer frente a estos acontecimientos agotadores, los profesionales deben aumentar su amor propio y cultivar un trabajo más armonioso y una vida personal más equilibrada.

Palabras clave: Conducta, enfermería, práctica profesional, calidad de vida, estrés psicológico.

INTRODUCTION

Stress, often called the "disease of the century", is a topic of interest among researchers and it is well known to interfere with institutional, social and personal activities. Sources of stress are influenced by each individual's thoughts, beliefs and interpretations of the world and by general events, although much about its influence remains unclear.1,2

Potential factors of stress (environmental, organisational, and individual) and the particular way that each individual manages stress manifest as physiological and/or psychological symptoms, all of which are consequences of a main source.2,3 This scenario infers that a given stimulus will or will not be a stressor, depending on how one experiences it from the point of view or the meaning one attributes to it. Sometimes, an event becomes stressful due to the manner in which it is interpreted. Thus, a stress source can be positive or negative according how one adjusts to and interprets it.2,4

Stressor stimuli include challenging external and internal events in response to which individuals must generate adaptation strategies to preserve their life and welfare. When an individual fails to adapt to a stressor, behavioural and psychological effects will occur due to this breakdown of homeostasis.5,6 An individual under stress can have various diseases due to decreased immunity and may also be less productive as a result of a decreased ability to concentrate and think coherently.7-9 To re-establish homeostasis, we must understand the manifestations of stressor agents in organisations and their members. Because individuals' emotions can affect their quality of life and that of the people around them, a basic understanding of the signs, symptoms and consequences of stress is essential for providing effective therapy in both personal and professional spheres of life.10

Unfortunately, individuals in contemporary society are constantly vulnerable to stress and are increasingly developing psychophysiological diseases. There is vast literature on general illnesses linked to stress and on stress-related decreases in work productivity. Thus, education in stress management should become a necessary part of healthcare in societies where stress-related disorders have important impacts.11 To promote the safety and health of at-risk workers, these illnesses should be considered among the everyday activities12 and the occupational risks (physical, chemical and biological) that management monitors in addition to ergonomic and psychosocial factors.11

Nurses, for example, are one of the largest healthcare workforces in the world, and they provide individual, family and community care.13 The nursing profession can be stressful because of the organisational structure of nurses' work and its psychological demands. Nurses' activities include disease prevention, health promotion, recovery and rehabilitation in addition to administrative activities.14,15 Studies of occupational stress in nurses have not yet established whether any specific function or specialty of the profession is more stressful than others. Nurses' sources of stress vary, although some stressors are common to nurses working in any position or environment. Due to this problem, these professionals spend most of their time with patients and have little time to take care of themselves. While trying to meet the demands of their stressful occupation, they often fail to recognise the influence of stress on their own health.

To address this problem, this study analysed the psychophysiological consequences of stressors from work and everyday life in nursing professionals, describing ways in which they can improve their personal and occupational well-being.

METHODS

Type of study: The study was a descriptive, exploratory and population-based study that followed a quantitative and qualitative approach and analysed the profile of everyday and organisational behaviour related to the stress of nursing professionals in a public hospital.

Characterisation of the work location: The study location was a public university hospital in the state of Goias, Brazil. The unit is certified by the Ministries of Health and Education as a teaching hospital and offers services exclusively to the Unified Health System. The hospital is considered a reference for several medical specialties in Goias, Brazil.

Population and sample: The participants were members of the nursing staff of the hospital and were active and assigned to several units. The professionals were informed of the objectives and characteristics of the study and those nurses who agreed to participate were asked to sign an Informed Consent Form (ICF).The inclusion criteria required that they were active nursing professionals, that they consented to participate in the study and that they had a minimum of one year of experience in the hospital. The participants also required to have work activities consistent with their profession and the associated employment relationship with the institution, including convened links. The exclusion criteria prohibited the following individuals from being included in the study sample of 408 professionals: temporary workers (volunteers and fellows), inactive workers, active professionals who refused to participate in the study, nurses with less than one year of experience in the hospital, nurses whose work tasks deviated from nursing activities and whose work responsibilities were in other fields, nurses who were in the service of other university organisations and nurses who participated in validating the instrument for data collection.

Ethical aspects and strategies for data collection: The study was conducted in accordance with Resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council (Ministry of Health, 1996) and approved by the Ethics in Human and Animal Medical Research (CEPMHA) of the studied hospital according to protocol number 005/2010.

The procedures for data collection involved two phases. Phase 1 involved an administrative survey of the nursing staff in the institution's directory, which was conducted by the institution's personnel department. This survey identified the nursing professionals, their positions and their respective work fields as well as professionals who were on leave or who had moved to other departments. Phase 2 was a self-administered form containing both open-ended and close-ended questions that was delivered together with the ICF. Both documents were given to the participants to fill out at their convenience and were retrieved at the participants' request.

Design of the data collection instrument: Research on stress in the nursing profession has only used scales that measure occupation-related stress. To achieve the objectives of the study related to the behavioural changes resulting from the stress of working and everyday life among nursing professionals, the data collection form was divided into two sections. The first section used close-ended questions to collect the following sociodemographic data: gender, marital status, education, complementary study activities, employment and position held and work experience as a nurse in the studied hospital. The second section of the form used both open- and closed-ended questions to collect the following data related to stress, work and everyday life: the respondent's view of stress, personal manifestations of stress, stimuli and stressful demands, illnesses and the use of medications and other therapeutic resources.

Statistical analysis: The following two-stage approach was used to improve the analysis of the data obtained through the questionnaire:

Stage 1 - Qualitative: This stage used content analysis for the open-ended questions, whose three proposed steps were employed:

a. Pre-analysis: reading and detailed description of the responses and the development of indicators to support the creation of categories (e.g., stress is a disease, stress can lead to disease, stress is a set of diseases).

b. Exploration of the material: data grouping by similarities and the consolidation of the content into the identified categories.

c. Inference: the classification of the categories into numerical units to create a raw data file and to establish the basis for the quantitative study.

Stage 2 - Quantitative: A raw data file was prepared as an Excel spreadsheet from the numeric values inferred from the qualitative data and obtained from both the objective and the subjective questions (categorised by similarity). Consistency tables, descriptive statistics and nonparametric tests were constructed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAEG), version 7.1. Chi-square tests were used to assess the statistical significance of differences (p<0.05), allowing for a comprehensive study of the population.

RESULTS

This study involved 408 nursing professionals who completed a self-evaluation about stress and stress-related behaviour. The participants were asked whether they perceived themselves as stressed. Among the 408 nursing professionals surveyed, 357 (87.5%) were female and 257 (63.0%) were married. The largest proportion, 141 (34.5%) participants, was middle-aged (41-50 years).

A statistically significant (p=0.001) relationship was observed between the number of employment contracts and stress. Of the 408 professionals analysed, 205 (50.3%) were bound by two employment contracts; of these, most of them described themselves as "sometimes stressed". Two participants (0.4%) each had four employment contracts (table 1).

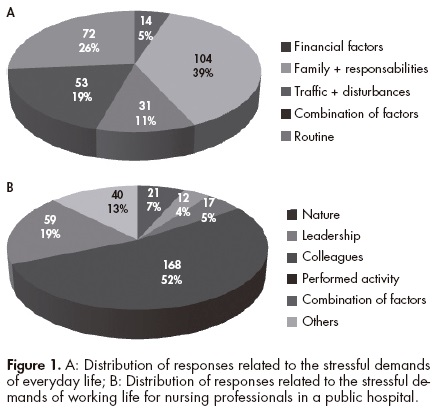

Respondents were also asked which factors caused the most stress. Of those professionals who reported sources of stress in everyday life, 104 (39%) named family and responsibilities as a stressor stimulus. The daily routine was named by 72 (26%) as a focus of stress. In addition, 53 (19%) reported that the stress of everyday life had several contributors, including family (especially child care), the reconciliation of roles at home and in the workplace, finances, lack of leisure time and relocation for work. This group is denoted in figure 1A as "Combination of stressors". In addition, 31 (11%) professionals reported transit and traffic disturbances as stressors. Another 14 (5%) respondents viewed financial concerns as a specific cause of stress in their everyday lives. The frequencies of everyday stressors in the sample were statistically analysed and p=0.001 was found, thus indicating referential significance (figure 1A).

A similar approach was used to analyse the demands of work-related stress (figure 1B). More than half of the respondents, 168 (52%), emphasised that the main stress factor was the activities involved in nursing. Another 59 (19%) reported multiple stressors (work responsibilities, colleagues, leadership, nursing activities, among others) denoted in figure 1B as "Combination of factors." Another 12 (4%) respondents named hospital leadership as a stressor stimulus. It is important to note that the 40 subjects (13%) who responded "other", referring to other stress factors at work, reported that these issues were related to infrastructural, human and material deficits; these responses also included complaints about the healthcare system. In the content analysis, these responses are included in the "performed activity" category because they capture activities involved in the nursing profession.

Next, 106 (62.6%) of 169 professionals who reported having an illness perceived themselves as "sometimes stressed", 45 (26.8%) reported feeling "stressed" and only 18 (10.6%) claimed that they were "not stressed." Of 55 (32.4%) professionals affected by chronic-degenerative diseases, 29 (17.1%) perceived themselves as "sometimes stressed" and 19 (11.2%) as "stressed". No professional with a neurological ailment, immune disorder (leukopenia, lupus, allergies, or herpes), rheumatological disorder (fibromyalgia or arthritis), dermatological condition (psoriasis) or pulmonary condition (asthma) rated him- or herself as "not stressed". Of the 169 professionals who reported having a disease, 85.5% used some kind of medicine. Among the professionals who reported chronic diseases and neurological diseases 54 (32%) and 30 (18%), respectively, used medication as part of their treatment. Pharmacotherapy was the most common approach to treating medical conditions in this sample. A highly statistically significant relationship was observed (p=0.001) between illnesses and the perception of stress (table 2).

Practices related to the use of music, walking, sports, leisure activities and other therapies (yoga, psychotherapy, occupational therapy, auriculotherapy, among others) may be included in strategies for coping with stress and illness. Most professionals in the sample did not include these non-pharmacological treatments as part of their coping strategies. Data from the questionnaires indicate that many respondents preferred sitting in silence, sleeping or watching television to alleviate their stress (table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study focused on self-perceived stress in nursing professionals. The results suggest that most of them perceive themselves as at least somewhat stressed, indicating that they acknowledge the effect of stress in their lives. The workers were affected by several types of diseases, probably because of organic imbalances caused by chronic stress. Pharmacotherapy was the main strategy used to alleviate their psychophysiological problems and most professionals never used alternative therapies (e.g., psychotherapy) as a way to combat their stress.

Respondents were able to reflect on their stress level before rating it. The ability to reflect is seen as a positive aspect of the research given the stressful conditions of the nursing work environment and the double and triple work shifts that some respondents reported. These factors predisposed the nursing professionals to neglect their own healthcare, failing to take steps for the prevention or early detection of diseases that may be related to occupational activities or working conditions.

The results concerning the respondents' state of stress were consistent across sociodemographic profiles. The prevalence of females (87.5%) in the study sample is common in research involving the nursing and related to the feminisation of the profession. In nursing, reports of greater stress for females should be analysed in a more comprehensive way to account for the burden of multiple roles (wife, mother, worker) and work shifts in addition to other direct effects on physical and mental health.

The description "sometimes stressed", reported by 262 workers (64%), makes sense; no one can live in a constant state of stress, as it would soon result in death as a consequence of excess organic wastage. The proportion of responses in this category did not vary with gender. Furthermore, a group of 205 (50.3%) of the nursing professionals had two employment contracts and more than half of the nurses in this group described themselves as "sometimes stressed". The characterisation of insufficient finances as a manifestation of everyday life stress explains the 158 workers (38.7%) who reported stress in their lives despite having only one job. Many possibilities for number of contracts and stress' analysis are reported and the results are in line with the findings of other researchers. However, individual differences are also noted, even in responses to the same stressful stimulus.

It is well known that nursing professionals have begun taking double, triple and more shifts to achieve a reasonable financial situation. A single employment contract does not reflect the overall reality and may not be an option given the general difficulties of finding positions in the competitive nursing job market.16 Long work hours in multiple jobs, together with a lack of time for family and for taking care of oneself, causes nursing professionals to become fatigued and stressed.

Stress-related diseases develop due to an imbalance in the harmony between body and mind. A key step in the treatment of these diseases is to increase knowledge about the relationship between stress and disease. Currently, science indicates that stress of excessive intensity and/or duration can produce psychophysiological changes in the body at any psychoneuroimmunology level.6,17,18 In an analysis of behavioural changes as prevalent pathologies, 169 professionals claimed to suffer from an illness. Chronic-degenerative, neurological and endocrine diseases were reported frequently, as were heart, gastric and rheumatic diseases. For chronic-degenerative diseases, 55 cases (32.4%) were identified and only seven of these professionals (4.1%) characterised themselves as "not stressed". Among the diseases triggered by stress from psychosocial burdens, depression was grouped with the neuropathies for analysis, as were anxiety, panic, migraine and others. The data indicated that 33 professionals (19.6%) were affected and of these none rated themselves as "not stressed".

Several studies in the stress management literature emphasise the harmful behavioural aspects, including morbidity and mortality,19,20 and note the existence of research that proposes ways of controlling the negative aspects of stressful work and daily life situations.17,21 The maintenance of life depends on the capacity of the organism to prepare the body for "fight or flight" when confronting stressors in the environment.18,22 We highlight depression because it is an important effect of stress that may increase suffering and reduce welfare for affected individuals. Depression may also aggravate existing diseases or facilitate the appearance of new medical conditions to which the individual is predisposed.23-25

Dermatological diseases are also aggravated by stress. The emotional stress of patients with skin diseases may be associated with the embarrassment of having visible lesions. Psoriasis, for example, involves an imbalance of the immune system, genetic predisposition and triggering factors, including stress.26 This problem was reported by three professionals (1.8%).

The main characteristic of the rheumatic diseases reported in the sample (fibromyalgia and arthritis) is intense pain and any painful stimulus can activate the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis that regulates stress reactions.27 Five professionals (3.0%) reported having one of these conditions, all of whom described themselves as "sometimes stressed". Some pathologies, however, still receive little attention from researchers, such as systemic erythematosus lupus, a multi-systemic autoimmune disease that is considered a rheumatic disease,28 but in our study it is included in immunopathies (lupus, herpes, leukopenia and allergies). Nine cases (5.3%) were identified among the investigated workers, five of whom (1.2%) had more than one job and none regarded themselves as "not stressed". Given these considerations, the emergence of pathological cases involving the endocrine system in 29 professionals (17.2%) is not surprising (the endocrine system is activated by stress). Note that these cases do not include diabetes, which was included in the category of chronic-degenerative diseases.

A vast body of research in a number of fields has investigated how illnesses are exacerbated by the influence of psychological stress. This change occurs because stress provides the trigger for predisposing factors or, through immune system disturbance, allows for the emergence of opportunistic infections.6,7,9 The use of drug therapy was widespread among professionals who reported having a medical condition. It is well known that for greater therapeutic effectiveness, non-pharmacological therapies must be incorporated into treatment. So, we asked the nurses about walking, music, sports, leisure and complementary therapies as potential ways of dealing with stressful situations. Most reported that they "rarely" or "never" enjoy these benefits. In general, these responses seemed to be related to the overload that nurses suffer in the workplace. Such behaviour, however, is contradictory for healthcare professionals who know the benefits of health and quality of life related to adequate nutrition and self-care.

The commitment to maintain the control of one's pathology and make changes in one's lifestyle is a great challenge for these professionals. They devote so much time to work and family and sometimes to the events of everyday life that they neglect their own health. The double shifts that half of the sample reported increase fatigue and ultimately reduce the amount of time devoted to self-care.

Overall, as previously observed, stress is a dynamic process that may be either aggravated or reversed depending on the coping techniques that an individual uses. To reduce stress, an individual must use specific stress management techniques. Strategies to promote health in workers in large hospitals have been the topic of intense discussions. Mental health is particularly important to monitor because it is the first area to be affected, whereas physical health problems merely reflect the consequences of the stress response.21,29,30

Without the use of stress management strategies, it is likely that stress-related illnesses will increase in severity, weakening the immune system and consequently increasing exposure to disease.7,18,31 When a coping strategy focuses on the problem, individuals try to deal directly with the stressful situation itself and test several strategies to ameliorate it. When coping is focused on emotion, individuals employ emotional or cognitive strategies that change their perception of the stressful situation; these strategies tend to alleviate the problem or cause the individual to avoid it.29,32,33

Overall, several attempts have been made to apply the recommendations of studies on stress in the workplace and to instruct workers in coping mechanisms and multidisciplinary partnerships. A proper intervention should focus on solutions that involve the active participation of institutional employers. Workers who do not exercise regularly generally have higher levels of stress. Physical activity is also associated with psychosocial benefits; for example, the social interaction and interpersonal communication that take place during exercise can serve as strategies for coping with stressful situations. If nothing is done to alleviate stressors, workers' clinical conditions may emerge or worsen. Overwork may make appropriate periodic medical monitoring difficult. Many diseases may result from the effects of stress and lack of an adequate clinical follow-up. Although the worker may not realise it, the body responds to a lack of care through the emergence of chronic diseases, which could be prevented or detected earlier through medical monitoring and changes in behaviour and lifestyle.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Isabel Dias Carvalho from the University of Rio Verde (Goiás-Brazil) for contributions to the statistical analysis of this study. We also thank all of the professionals from the nursing staff who contributed to this study.

REFERENCES

1. Backé EM, Seidler A, Latza U, Rossnagel K et al. The role of psychosocial stress at work for the development of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2012;85:67-79. [ Links ]

2. Campeau S, Liberzon I, Morilak D, Ressler K. Stress modulation of cognitive and affective processes. Stress 2011;14:503-519. [ Links ]

3. Gates DM, Gillespie GL, Succop P. Violence against nurses and its impact on stress and productivity. Nurs Econ 2011;29:59-66. [ Links ]

4. Lai MC, Huang LT. Effects of early life stress on neuroendocrine and neurobehavior: mechanisms and implications. Pediatr Neonatol 2011;52:122-129. [ Links ]

5. O'Connor TG, Spagnola ME. Early stress exposure: concepts, findings, and implications, with particular emphasis on attachment disturbances. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2009;3:24. [ Links ]

6. Vedhara K, Fox JD, Wang EC. The measurement of stress-related immune dysfunction in psychoneuroimmunology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1999;23:699-715. [ Links ]

7. Kang DH, Rice M, Park NJ, Turner-Henson A et al. Stress and inflammation: a biobehavioral approach for nursing research. Western J Nurs Res 2010;32:730-760. [ Links ]

8. Lie JA, Kjuus H, Zienolddiny S, Haugen A et al. Night work and breast cancer risk among Norwegian nurses: assessment by different exposure metrics. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:1272-1279. [ Links ]

9. Rath E, Haller D. Inflammation and cellular stress: a mechanistic link between immune-mediated and metabolically driven pathologies. Eur J Nutr 2011;50:219-233. [ Links ]

10. Vagharseyyedin SA, Vanaki Z, Mohammadi E. The nature nursing quality of work life: an integrative review of literature. West J Nurs Res 2011;33:786-804. [ Links ]

11. Balch CM, Shanafelt T. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin 2011;21:417-430. [ Links ]

12. Farias SM, Teixeira OL, Moreira W, Oliveira MA et al. Characterization of the physical symptoms of stress in the emergency health care team. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2011;45:722-729. [ Links ]

13. Takeuchi T, Yamazaki Y. Relationship between work-family conflict and a sense of coherence among Japanese registered nurses. Jpn J Nurs Sci 2010;7:158-168. [ Links ]

14. Beck CT. Secondary traumatic stress in nurses: a systematic review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2011;25:1-10. [ Links ]

15. Diiorio C, Hinkle JL, Stuifbergen A, Algase D et al. Updated Research Priorities for Neuroscience Nursing. J Neurosci Nurs 2011;43:149-155. [ Links ]

16. Puschel VA, Inacio MP, Pucci PP. Insertion of USP nursing graduates into the job market: facilities and difficulties. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2009;43:535-542. [ Links ]

17. Dragos D, Tanasescu MD. The effect of stress on the defense systems. J Med Life 2010;3:10-18. [ Links ]

18. Vermes I, Beishuizen A. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to critical illness. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;15:495-511. [ Links ]

19. Abrams TE, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal GE. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on surgical mortality. Arch Surg 2010;145:947-953. [ Links ]

20. Rao U. Comorbidity between depressive and addictive disorders in adolescents: role of stress and HPA activity. US Psyc 2010;3:39-43. [ Links ]

21. LaMontagne AD, Keegel T, Vallance D. Protecting and promoting mental health in the workplace: developing a systems approach to job stress. Health Promot J Aust 2007;18:221-228. [ Links ]

22. Goligorsky MS. The concept of cellular "fight-or-flight" reaction to stress. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol 2001;280:F551-561. [ Links ]

23. Brown AD, Barton DA, Lambert GW. Cardiovascular abnormalities in patients with major depressive disorder: autonomic mechanisms and implications for treatment. CNS Drugs 2009:23:583-602. [ Links ]

24. Montazeri A, Jarvandi S, Ebrahimi M, Haghighat S et al. The role of depression in the development of breast cancer: analysis of registry data from a single institute. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2004;5:316-319. [ Links ]

25. Schulz M, Damkröger A, Voltmer E, Löwe B et al. Work-related behaviour and experience pattern in nurses: impact on physical and mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2011;18:411-417. [ Links ]

26. Zmijewski MA, Slominski AT. Neuroendocrinology of the skin: An overview and selective analysis. Dermatoendocrinol 2011;3:3-10. [ Links ]

27. Imrich R, Rovensky J. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2010;36:721-727. [ Links ]

28. Shah D, Wanchu A, Bhatnagar A. Interaction between oxidative stress and chemokines: Possible pathogenic role in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Immunobiology 2011;216:1010-1017. [ Links ]

29. Faragher EB, Cass M, Cooper CL. The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med 2005;62:105-112. [ Links ]

30. Murgia C, Sansoni J. Stress and nursing: study to evaluation the level of satisfaction in nurses. Prof Inferm 2011;64:33-44. [ Links ]

31. Galbraith ND, Brown KE. Assessing intervention effectiveness for reducing stress in student nurses: quantitative systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:709-721. [ Links ]

32. Hayes B, Bonnet A. Job satisfaction, stress and burnout associated with haemodialysis nursing: a review of literature. J Ren Care 2010;36:174-179. [ Links ]

33. Hassink-Franke LJ, van Weel-Baumgarten EM, Wierda E, Engelen MW et al. Effectiveness of problem-solving treatment by general practice registrars for patients with emotional symptoms. J Prim Health Care 2011;3:181-189. [ Links ]