Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Salud mental

Print version ISSN 0185-3325

Salud Ment vol.33 n.1 México Jan./Feb. 2010

Artículo original

Body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressures: gender and age differences

Insatisfacción corporal y presión sociocultural percibida: diferencias asociadas al sexo y a la edad

Igor Esnaola,1 * Arantzazu Rodríguez,1 Alfredo Goñi1

1 Faculty of Philosophy and Educational Sciences. University of the Basque Country, Spain

*Address:

Igor Esnaola. Avda. Tolosa, 70.

San Sebastián, 20018, Spain.

Tel: 94501 4037

E–mail: igor.esnaola@ehu.es

Recibido primera versión: 22 de julio de 2008.

Segunda versión: 17 de febrero de 2009.

Tercera versión: 29 de mayo de 2009.

Aceptado: 8 de julio de 2009.

Abstract

One important area of research that has emerged in recent years is the assessment of factors that contribute to the development of body image problems and, more concretely, to the development of body dissatisfaction. The female sociocultural beauty ideal, a constant object of research for over three decades now, is so ultra–thin that it is both unattainable and unhealthy. Likewise, the male beauty ideal of a lean yet muscular body is becoming an important issue for men, with poor body image sometimes leading to the adoption of numerous health–threatening behaviors, such as the use of steroids, ephedrine and deleterious dieting strategies.

Body image has been related with self–esteem, depressed mood, social anxiety and disordered eating. In recent years, physical self–perceptions are also studied from the parallel perspective of physical self–concept.

In general, women report much higher body dissatisfaction than men at all moments of life, from pre–adolescence to third age, although gender differences in adulthood and in the old age are less important than in adolescence. In the other hand, although women's dissatisfaction with their bodies remains fairly stable across the whole life span, the importance attached to physical appearance, specifically body size and weight, decreases with age.

The sociocultural framework has become the most empirically validated of all body image theories and this theory conceptualizes perceived sociocultural pressures as the principal cause of body dissatisfaction. Mass media, peer groups, and family are the three factors which have evolved as the most frequently assessed sociocultural perceived pressures of body dissatisfaction.

Previous research has paid considerable attention to gender and age differences in body dissatisfaction, but certain gaps still remain: a) more precise knowledge is required regarding men's body dissatisfaction; b) a comparative perspective of gender differences, in both body dissatisfaction and perceived pressure throughout the different stages of the lifecycle, is lacking; c) more information is required on the interpersonal variations involved in the relationship between body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressure; and d) a better understanding of the nature of sociocultural influences needs to be gained.

This research examines gender and age differences on body image –responses to the Garner's Eating Disorders Inventory–2 (EDI–2)– and perceived sociocultural pressures regarding body ideals –responses to the Questionnaire of Sociocultural Influences on the Aesthetic Body Shape Model (CIMEC–26), by Toro, Salamero, and Martínez–Mallén.

The sample group comprised 1259 participants: 627 adolescents, 271 young adults, 248 midlife adults, and 112 over 55's.

Results indicate that: a) body dissatisfaction is closely related to perceived sociocultural pressure; b) female participants show higher body dissatisfaction and perceive themselves more affected by sociocultural factors than their male counterparts; c) gender differences (in body dissatisfaction as in perceived sociocultural pressures) are greater for younger age groups than older; d) gender is a better predictor of body dissatisfaction and sociocultural perceived influences than age.

The results obtained provide a more comprehensive view of the relationship between body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressure during the different stages of the lifecycle, highlighting a number of close parallels between both variables. The new data also enables us to identify the young female population as the most susceptible to body dissatisfaction problems and the most vulnerable to sociocultural pressure, with the group of older women emerging as the one best able to cope with these problems. The study also identifies a number of themes which deserve further, more in–depth attention in the future. Tw o especially are worth noting: 1) this study analyses age differences (which may represent generational differences affected by cohort effects), rather than changes associated with age, since the inter–group differences observed correspond to people of different ages, but each separate group also represents a specific age at a specific moment in history; 2) it is important to continue exploring the different pressures exerted by different sociocultural factors (both perceived pressure and objective data on the influence of these factors), as well as the psychological mechanisms that enable some people to cope with these pressures better than others.

Key words: Body image, perceived socio–cultural pressures, body dissatisfaction, life span.

Resumen

Despierta gran interés teórico y social en nuestros días la identificación y medida de los factores que contribuyen al desarrollo de alteraciones de la imagen corporal y más concretamente al desarrollo de la insatisfacción corporal. El prototipo femenino de belleza dominante desde hace tres décadas en nuestra cultura propone una delgadez tan extrema que resulta no sólo inalcanzable, sino además muy poco saludable. El ideal masculino de belleza, por otro lado, demanda un cuerpo delgado, pero musculado, y éste ha adquirido gran importancia, por lo que con frecuencia se adoptan, a fin de mejorar la propia imagen, numerosas conductas peligrosas para la salud, como el consumo de esteroides, efedrina y dietas alimentarias dañinas.

La imagen corporal, conformada por las autopercepciones físicas de cada persona, ha sido objeto de numerosas investigaciones durante las últimas décadas en relación con rasgos psicológicos tan importantes como la autoestima, la depresión, la ansiedad o los trastornos alimentarios y, muy en especial, con la insatisfacción corporal. Está comprobado que, en general, las mujeres manifiestan mayor insatisfacción corporal que los hombres en todas las épocas de su vida, desde la preadolescencia hasta la tercera edad, si bien las diferencias de sexo en la edad adulta y en la tercera edad son menores que en la adolescencia. Por otro lado, aun cuando la insatisfacción de las mujeres con su cuerpo tiende a mantenerse estable a lo largo de todo el ciclo vital, es digno de señalar que la importancia conferida a la apariencia física y, más en concreto, al tamaño y peso corporal, decrece con la edad.

La presión sociocultural percibida aparece como principal causa de la insatisfacción corporal. Desde el enfoque sociocultural se señala, en concreto, a los medios masivos de comunicación, al entorno social próximo y a la familia como los tres elementos clave de dicha presión: cuanto más altos son los niveles de presión percibida con respecto a una imagen corporal idealizada, más se incrementa la preocupación por la imagen y por las estrategias de cambio corporal.

La investigación previa ha prestado considerable atención a las diferencias de sexo y de edad en cuanto a la insatisfacción corporal, pero se echan en falta: a) conocimientos más precisos sobre la insatisfacción corporal de los hombres; b) una perspectiva comparativa de las diferencias de sexo tanto en insatisfacción corporal como en presión percibida a lo largo de las distintas etapas del ciclo vital; c) mayor información sobre las variaciones interpersonales en la relación entre la insatisfacción corporal y la presión sociocultural percibida, y d) una mejor comprensión de la naturaleza de las influencias socioculturales.

Esta investigación trata de contribuir a la superación de estas carencias planteándose las siguientes hipótesis: 1) La insatisfacción corporal guarda estrecha relación con la presión sociocultural percibida; 2) las mujeres participantes, en todos los grupos de edad, muestran más insatisfacción corporal e indican sentirse más influidas por factores socioculturales que los hombres; 3) las diferencias de sexo (tanto en insatisfacción corporal como en presión sociocultural percibida) son mayores en los grupos de menor edad que en los de más edad; 4) el sexo resulta ser un mejor predictor de la insatisfacción corporal y de los influjos socioculturales percibidos que la edad.

Participaron en el estudio 1259 personas: 627 adolescentes, 271 adultos jóvenes, 248 adultos y 112 sujetos mayores de 55 años, quienes respondieron el Eating Disorders Inventory–2 (EDI–2), de Garner, que permite identificar la insatisfacción corporal, así como el Cuestionario de Influencias sobre el Modelo Estético Corporal (CIMEC), de Toro, Salamero y Martínez–Mallén.

Los resultados obtenidos proporcionan una visión más completa que la hasta ahora disponible acerca de las relaciones entre la insatisfacción corporal y la presión sociocultural percibida en las distintas etapas del ciclo vital: ambas variables guardan estrechos paralelismos; permiten, asimismo, identificar la población femenina joven como la más sensible a los problemas de insatisfacción corporal y de vulnerabilidad a la presión sociocultural, en tanto que el grupo de mujeres de más edad aparece como el que mejor sabe reaccionar ante los mismos.

Por otro lado, han permitido identificar temáticas, especialmente dos, que merecen seguir investigándose: 1) aquí se han analizado diferencias de edad (que bien pueden representar diferencias generacionales afectadas por efectos de cohorte) y no cambios asociados con la edad, ya que las diferencias intergrupales observadas corresponden a personas de diferentes edades, pero cada uno de dichos grupos tiene además la misma edad en un mismo momento histórico; 2) es preciso seguir indagando sobre la presión diferencial que ejercen unos y otros factores socioculturales (tanto la presión percibida como datos objetivos de influencia a unos u otros factores), así como sobre los mecanismos psicológicos que permiten a unas personas afrontar mejor que otras estas presiones.

Palabras clave: Imagen corporal, presión sociocultural percibida, insatisfacción corporal, ciclo vital.

INTRODUCTION

Society's conceptualization of the <<ideal>> female body, as reflected in massmedia, may influence women's body–image assessment. The female sociocultural beauty ideal, which has been pervasive for over three decades now,1,2 is so ultra–thin that it is both unattainable and unhealthy.3 Likewise, attention to men is increasing, and a recent review4 identified the male beauty ideal of a lean yet muscular body as becoming an important issue for men, with poor body image sometimes leading to the adoption of numerous health–threatening behaviors, such as the use of steroids, ephedrine, and deleterious dieting strategies.

Body image can be conceptualized as a multidimensional construct that represents how individuals <<think, feel, and behave with regard to their own physical attributes>>5 and has been the object of increasing scientific study over the past few decades for its relation with self–esteem, depressed mood, social anxiety, and disordered eating.6,7 Recently, physical self–perceptions have also been studied from the parallel perspective of physical self–concept.8–11

Women report much greater body dissatisfaction than men at all ages.12 Women's dissatisfaction with their bodies remains fairly stable across the life span,13 although importance attached to physical appearance, specifically body size and weight, decreases with age:6 older women reported greater <<cognitive control>> (reappraisal and lowering of expectations) over their bodies than younger women.14 Less well–documented than among women, it appears that men and boys are also increasingly reporting body dissatisfaction, but gender differences in adulthood are less important than in adolescence15 and in the old age.16

One important area of research that has emerged in recent years is the assessment of factors that contribute to the development of body image problems. From the sociocultural framework, the most empirically validated of all body image theories,17 the perceived sociocultural pressures are the principal cause of body dissatisfaction.18 Various factors have been implicated in the development of body image dissatisfaction. Awareness, internalization, and perceived pressures (massmedia, peer groups and family) are the three factors which have evolved as the most frequently assessed sociocultural factors.4 Perceived pressures are closely associated with body image; higher levels of perceived pressure are associated with greater body image concerns and body change strategies but men are not affected as much as women.12

Halliwell and Dittmar3 point out that the current increase in sociocultural emphasis on men's physical appearance affects young men much more than adult men. For men, age has negative connotations because it is related to the diminution of physical abilities, with changes in appearance being less important. Women, on the other hand, focus mainly on appearance and equate aging with reduced attractiveness. Older women are less affected by sociocultural pressure, so they tend to perceive themselves with less body dissatisfaction and are happier. Although physical appearance is important in adulthood for both men and women, the latter are specifically more worried about maintaining a youthful appearance as an indicator of their value and attractiveness and tend to engage in negative health behaviors, such as cosmetic surgery and diets.19 Men are less worried about changes in their physical appearance.20

Although previous research suggests that age is a significant variable and the association between sociocultural influences and body image decreases with age, Cafri et al.4 did not find that age was a significant moderator. Finally, in a study focusing on women aged between 63 and 75, Tunaley, Walsh and Nicolson21 found that older women resisted sociocultural precepts about attractiveness and thought that, because of their age, they should stop worrying about their physical appearance. It seems that the older age groups are least strongly influenced by massmedia.22 Overall, results support the tentative conclusion that the influence of exposure to media images regarding body image is weaker for men and boys than for women and girls.23

Previous research has focused on gender and age differences in body dissatisfaction; it has also studied the real or perceived influence of various sociocultural factors on body dissatisfaction, especially among women. However, further research is required: a) on body dissatisfaction in men; b) to gain a comparative perspective of gender differences throughout the different stages of the lifecycle; c) to identify interpersonal variations in the relationship between body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressure; and d) to gain a better understanding of the nature of sociocultural influences.

This research project aims to contribute to filling in these gaps in our current knowledge, by establishing the following hypotheses: 1) body dissatisfaction is closely related to perceived socio–cultural pressure; 2) female participants will report more body dissatisfaction and more perceived sociocultural pressure than men; 3) the older age groups (both women and men) will report less body dissatisfaction and less perceived sociocultural pressures than their younger counterparts; and 4) gender is a better predictor of body dissatisfaction and sociocultural perceived influences than age.

METHOD

Participants

The sample group comprised 1259 participants from the Basque Country (Spain), divided into four groups: adolescents (12–18 years old), young adults (19–30 years old), midlife adults (31–49 years old) and over 55's. The distribution is shown in table 1.

Instruments

Two questionnaires were used in this study:

• Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI–2):24 In our work, we used four scales: drive for thinness, bulimia, body dissatisfaction, and ineffectiveness feelings. However, in this paper we report only data related to the body dissatisfaction scale.

• Cuestionario de Influencias sobre el Modelo Estético Corporal (CIMEC).25 The Questionnaire of Sociocultural Influences on the Aesthetic Body Shape Model (CIMEC) was designed to measure the influence of the agents and situations that transmit the current body ideal. The validation was carried out with 118 young Spanish women: 59 anorectics and 59 non–anorectics, matched by age and social class. The questionnaire showed satisfactory internal consistency26,27 and appropriate sensitivity and specificity as a sound instrument for screening due to its relation to anorexia nervosa and sociocultural influences. An investigation on the differences corresponding to each of the 40 items in the original questionnaire enabled the researchers to isolate 26 items whose differences were statistically significant. These 26 items made up the definitive questionnaire (CIMEC–26). The factorial analysis revealed five factors:

1. Distress due to body image: this includes all the items that reveal anxiety when faced with situations that question the body itself, or envy of systematic and obvious social models. It is interesting that the same factors include the practice of dieting by the subject (example item: Does the arrival of summer distress him/her since it means wearing lighter clothes or a bathing costume?).

2. Influence of advertising: this includes all items related to the interest aroused by advertisements (example item: Do you feel the desire to consume low–calorie drinks when you hear or see an advertisement dedicated to them?).

3. Influence of verbal messages: this includes items dealing with the interest aroused by articles, reports, books and conversations (example item: Do conversations or comments about weight, calories, or figure, etc., attract you?).

4. Influence of social models: this includes items related to the interest aroused by the bodies of actresses/ actors, fashion models and passers–by (example item: When you see a movie, do you look at the actors or actresses, noticing specially whether they are fat or thin?).

5. Influence of social situations: this includes items dealing with the subjective social pressure experienced in eating situations, and items in which social acceptance is attributed to body ideals (example item: If you are invited to a restaurant or you eat in a group situation, do you worry about the amount of food you may be forced to eat?).

In our study we applied the reduced version (CIMEC–26), re–writing the items that originally could only be answered by women so that they could be answered equally by both women and men. Internal consistency, measured using Cronbach's alpha, was satisfactory (α =.82 for men and α =.90 for women). We did not use the first factor: <<distress due to body image>>, since we used the EDI questionnaire to measure body dissatisfaction.

Procedure

Questionnaires were administered by the authors of this study in collaboration with the research group members, and instructions were provided on how to complete them. Participation was voluntary, and participants were clearly informed that they could withdraw from the process at any moment. All participants were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity, in order to reduce social desirability. The questionnaires were administered collectively, and a random inter–group equiponderation was carried out to control the test threat. For the adolescent sample, the questionnaires were administered in three public and three private secondary schools. The young adult sample was made up mostly by students from the University of the Basque Country (Spain). In order to find the adult and older age groups, we contacted civic centers, gymnasiums, handicraft groups, retired persons' clubs, etc., so as to put together a heterogeneous sample.

All participants were selected by means of a stratified random sampling design: firstly, schools/social centers from various towns were selected randomly; and secondly, classes/groups from the schools/social centers were selected (also randomly) within the study's target age range).

In this cross–sectional study, statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS 11.5 program for Windows. Specific analyses were carried out to test for parameter conditions; results showed that the scales met these parametric conditions. To examine the effects of gender and age, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out, alongside a Tukey post–hoc test to determine differences between the groups. Similarly, the univariate general linear model and the multiple regression analysis were used to analyze the size of the effect and to determine whether gender or age was the best predictor of body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressures.

RESULTS

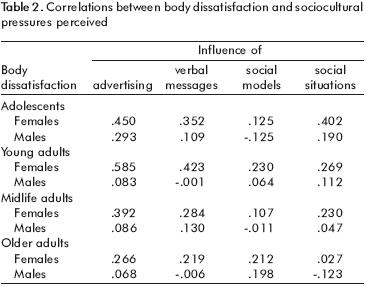

Table 2 shows the Pearson correlations between body dissatisfaction and perceived pressures.

Among women, correlations between body dissatisfaction and the CIMEC scales were significant, especially in adolescents and young adults. In the midlife adult group, significant correlations were found in three out of four scales (influence of advertising p=.001, influence of verbal messages p = .001 and influence of social situations p=.005), and finally, in the over 55 age group, significant correlations were found between body dissatisfaction and influence of advertising (p=.031). Out of the four sociocultural factors, the one which correlated highest with body dissatisfaction in the female sample was the influence of advertising in all ages.

Among men, significant correlations were found in adolescents between body dissatisfaction and influence of advertising (p=.001), as well as between body dissatisfaction and influence of social situations (p=.003). Out of the four sociocultural factors, the one which correlated highest with body dissatisfaction in the male sample was different for each group. For adolescents, it was the influence of advertising; for young adults, it was the influence of social situations; for midlife adults, the influence of verbal messages; and for older adults, the influence of social models. However, only in the case of adolescents was the correlation significant.

These results provide empirical evidence of that postulated in the first hypothesis (the close relationship between body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressure); and support the third hypothesis, which postulated that the older age groups (in both women and men) would report less body dissatisfaction and less perceived sociocultural pressures than their younger counterparts.

The results presented in table 3 attest to what was postulated in hypotheses two and three.

Women reported greater body dissatisfaction than men across all age groups (adolescents t(624)=8.998, p=.001; young adults t(269) = 4.190, p = .001; midlife adults t(243)=5.222, p=.001; and older adults t(107)=2.789, p=.006). In relation to sociocultural influences, women are more affected than men by the influence of advertising (t(624)=7.602, p=.001), influence of verbal messages (t(624)=10.566, p=.001), influence of social models (t(624)=3.478, p=.001) and influence of social situations (t(624)=2.334, p=.020) in the adolescent group; by influence of advertising (t(269)=5.928, p=.001) and influence of verbal messages (t(269)=3.026, p=.003) in the young adult group; by influence of advertising (t(245)=6.879, p=.001), influence of verbal messages (t(245)=4.134, p=.001) and influence of social models (t(245)=2.664, p=.008) in the midlife adult group; and by influence of verbal messages (t(107)=2.484, p=.015) in the older adult group. These results confirm the second hypothesis, which postulated that women would report greater body dissatisfaction and greater perceived sociocultural pressures than men.

Among women, the body dissatisfaction (F(3, 697)=4.831, p=.002), influence of advertising (F(3, 697)=4.000, p=.008), and influence of social models (F(3, 697)=15.258, p=.001) scales decrease over the life span, from adolescence to old age; in other words, female adolescents report greater body dissatisfaction and are more affected by advertising and social models than their older counterparts. On the other hand, women over the age of 55 report the least body dissatisfaction and are least affected by advertising and social models. These results confirm the third hypothesis: that the older age groups would report less body dissatisfaction and less perceived sociocultural pressures than the younger ones.

Given that differences were found between the groups, Tukey multiple comparison tests were used to determine which specific groups were statistically different. The results show that, in body dissatisfaction, there were significant differences between the adolescent and midlife adult groups (p=.006); whereas in influence of advertising, variations were found between the adolescent and older adult groups (p=.012). Finally, in influence of social models, significant differences were found between the adolescent and midlife adult groups (p=.001), the adolescent and older adult groups (over 55's) (p=.001), the young adult and midlife adult groups (p=.002), and the young adult and older adult groups (p=.001).

Among men, significant differences were found regarding age in influence of advertising (F(3,552)=3.325, p=.020), influence of verbal messages (F(3,552)=4.388, p=.005), and influence of social models (F(3,552)=11.568, p=.001). The development is not linear in any scale. Surprisingly, the over 55 group is the most affected by influence of advertising. However, the group of young adults is the most affected by verbal messages and social models. Among men, the results are not completely concordant with the third hypothesis, which predicted that older age groups would exhibit less body dissatisfaction and less perceived sociocultural pressures than their younger counterparts.

Given that differences were found between the groups, Tukey multiple comparison tests were used to determine which specific groups were statistically different. Results show that in influence of advertising, significant differences were found between the midlife adult and over 55 groups (p=.028). In influence of verbal messages differences were found between adolescents and young adults (p=.003). And finally, in influence of social models significant statistical differences were found between the adolescents and midlife adults (p=.003), adolescents and older adults (p=.002), young adults and midlife adults (p=.001), and young adults and older adults (p=.001).

Likewise, a multivariate regression was performed with gender, age, and the interaction between the two, in order to determine which of the variables was the best predictor of body dissatisfaction and sociocultural pressures. Results are shown in table 4.

The multiple regression analysis enables us to estimate the weight or influence of the gender and age factors in the different scales applied and, therefore, to predict results in accordance with said factors.

These data confirm that men manifest less body dissatisfaction and perceive themselves as less influenced by aesthetic corporal models than women. Furthermore, both body dissatisfaction and perception of the influence of different sociocultural factors decrease in older age groups, although in some cases this decrease is only very minor. Consequently, the gender variable is, in general, more significant than age when explaining the differences observed in the different scales.

At the same time, a univariate general linear analysis was also conducted to observe the influence of the factors analyzed, i.e. gender, age and the interaction between them. Results are shown in table 5.

As is evident in the table, gender has a greater capacity, or explains a greater proportion of variability in scores on the body dissatisfaction, influence of advertising and influence of verbal messages scales. In the influence of social models and influence of social situations scales, age explains a greater proportion of variability, although in the latter scale the difference is minimal.

Therefore, as stated above, gender has a greater capacity than age to explain the differences observed in the scales analyzed, thus confirming the fourth hypothesis.

DISCUSSION

The adoption of the thin ideal (for women) or a muscular body (for men) for oneself is, in fact, quite sensible in a society which values appearance so much and in which being attractive does confer considerable social advantage.

Research, however, continues to focus on younger populations such as children, adolescents and young adults, neglecting to examine body image in adult populations. Therefore, the goal of this study was to examine the relation of sex and age with body image and perceived sociocultural pressures regarding body ideals from adolescence through old age. Results supported the idea of sex as a significant variable, extending previous studies,12,15,20,28,29 since women scored worse than men in the adolescent (in four out of five scales), young adult (in three out of five scales) and midlife adult groups (in four out of five scales): in other words, body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressures regarding body ideals are higher in women. As a number of authors have pointed out,3,19 women are specifically more worried about maintaining a youthful appearance as an indicator of their value and attractiveness; men are less worried about changes in their physical appearance. In the over 55 age group, we only found significant differences in the influence of verbal messages scale. Therefore, it seems that sex differences decrease with age.

With regard to age, among women, the body dissatisfaction, influence of advertising and influence of social models scales decrease significantly from adolescence to the over 55 age group; in other words, the worst body image and the strongest influence of advertising and social models appear during adolescence and then decrease gradually until the later stages of life. These results are consistent with previous empirical studies reporting that body dissatisfaction and the influence of sociocultural pressures are higher in ages like adolescence or young adulthood than in older adults.30 This finding is consistent with those studies2,6,26 which indicate that the importance attached to physical appearance decreases with age. We agree with some authors14,31 that say that there is a greater acceptance of age–related changes in appearance; it seems that older women reported greater <<cognitive control>> (reappraisal and lowering of expectations) over their bodies than younger women. Older women are less affected by sociocultural pressure, so they tend to perceive themselves with less body dissatisfaction and are happier. It was also found21 that older women resisted sociocultural prescriptions about attractiveness and thought that, because of their age, they should stop worrying about their physical appearance.

However, this does not mean that the association between body dissatisfaction and the pressure of sociocultural factors disappears in more advanced ages. In midlife and older adults, strong associations exist between body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressures, although they are weaker than in younger adults.

Among men, the development of body perception and the pressure of sociocultural factors is not linear, as it is for women. The results vary according to the scale analyzed, although we should add that the young adult group is the one most affected by influence of verbal messages and social models. This means that, in contrast to women, among whom the group with the worst self–perception is the adolescent one, for men, this social pressure is perceived more acutely during young adulthood. For men, age has negative connotations because it is related to the diminution of physical abilities, with changes in appearance being less important.3

When the correlations were analyzed, the results showed that the association between body image and the pressure of sociocultural factors was higher among women than among men. Stronger associations were found between body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressures in women than in men, a finding which coincides with previous studies,31 and which indicates that the influence of sociocultural factors is a powerful predictor of body dissatisfaction, especially in women. Likewise, in women particularly, the association between body dissatisfaction and sociocultural influences decreases with age.

In relation to perceived sociocultural pressures, we wanted to analyze the relative importance of various socio–cultural influences perceived on body dissatisfaction. In most age groups, the influence of advertising appears to be a more important factor than verbal messages, social situations, or social models. That is consistent with previous studies in which these are also found positively correlated with body dissatisfaction factors as: the quantity of magazines read;32 the total time spent viewing soap operas on television;33 the thin media images34 and media broadcasts;35 the viewing of fashion magazines,36 and advertisements about beauty ideals.37

This study has contributed to gaining a more comprehensive view of the relationship between body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressure, with close parallels being highlighted between the two variables. It also identifies the young female population as the most susceptible to these types of problems, with the group of older women emerging as the one best able to cope with them.

Furthermore, the study also identifies a number of themes which deserve further, more in–depth attention in the future. Three are worth noting especially: 1) this study analyses age differences (which may represent generational differences affected by cohort effects), rather than changes associated with age, since the inter–group differences observed correspond to people of different ages, but each separate group also represents a specific age at a specific moment in history; 2) it is important to continue exploring the different pressures exerted by different sociocultural factors (both perceived pressure and objective data on the influence of said factors), as well as the psychological mechanisms that enable some people to cope with these pressures better than others; 3) the relationship between body image and physical self–concept, a related construct studied fairly extensively over the last two decades.10,11

The results obtained could be used for the design of prevention and intervention programs, basically for women since they are the most affected. One of the main purposes of any program must be to make women aware of the enormous pressure they are under, and the negative influence that this pressure exerts over their body perception. Thus, it would be extremely useful and beneficial for both their physical and psychological health to learn to compare themselves with real models and understand that it is necessary to change the present situation because the ideal body for women is becoming more and more unreal. This model poses a serious health risk because women are constantly striving for an ideal body shape that is practically unattainable. If we are to take the task of alleviating negative body image seriously, thus reducing the occurrence of consequent clinical problems, it may be necessary to focus on preventing the internalization of unrealistic sociocultural body ideals and detrimental appearance beliefs.18 The healthiest advice, both from a physical and psychological point of view, would be to offer women criteria and reference values on which to consolidate their self–esteem, criteria closer to psychological and human qualities, and further removed from a physical image which allows too little room for maneuver and which, at the end of the day, only reflects the more external and superficial part of a person. As regards men, further research is still required.

The two principal achievements of the study are as follows: a) it provides further information about the association between body dissatisfaction and sociocultural pressure; and b) it identifies a number of important themes which deserve more in–depth investigation in the future. Nevertheless, it is important to see whether these results are confirmed by other models of sociocultural pressure. Here, in accordance with Toro et al. (1994), it was assumed that perceived cultural pressure could be internally divided into four factors: influence of advertising, influence of verbal messages, influence of social models, and influence of social situations. However, some reviews of this model10 indicate that finer distinctions may provide better results. If these finer distinctions were to be applied, they would lend greater complexity and nuance to the results outlined in this report.

REFERENCES

1. Berscheid E, Walster E, Bohrnstedt G. Body image: The happy American body, a survey report. Psycho Today 1973;11:99–131. [ Links ]

2. Thompson JK. Handbook of eating disorders and obesity. New York: Wiley; 2004. [ Links ]

3. Halliwell E, Dittmar H. A qualitative investigation of women's and men's body image concerns and their attitudes toward aging. Sex Roles 2003;49:675–684. [ Links ]

4. Cafri G, Yamamiya Y, Brannick M, Thompson K. The influence of sociocultural factors on body image: a meta–analysis. Clin Psych Science Prac 2005;12(4):421–433. [ Links ]

5. Muth JL, Cash TF. Body image attitudes: what difference does gender make? J Community Appl Soc Psych 1997;27:1438–1452. [ Links ]

6. Tiggemann M. Body image across the adult life span: stability and change. Body Image 2004;1:29–41. [ Links ]

7. Lora–Cortez CI, Saucedo–Molina T. Conductas alimentarias e imagen corporal de acuerdo al índice de masa corporal en una muestra de mujeres adultas de la ciudad de México. Salud Mental 2006;29(3):60–67. [ Links ]

8. Goñi A, Rodríguez A. Variables associated with the risk of eating disorders in adolescence. Salud Mental 2007;30(4):16–23. [ Links ]

9. Infante G, Goñi E. Actividad físico–deportiva y autoconcepto físico en la edad adulta. Rev Psicodidáctica 2009;14(1):49–62. [ Links ]

10. Goñi A (Coord.). El autoconcepto físico: psicología y educación. Madrid: Pirámide. [ Links ]

11. Esnaola I, Goñi A, Madariaga JM. El autoconcepto: perspectivas de investigación. Rev Psicodidáctica 2008;13(1):69–96. [ Links ]

12. Mccabe MP, Ricciardelli LA. Body image dissatisfaction among males across the life span. A review of past literature. J Psychosom Res 2004;56:675–685. [ Links ]

13. Montepare JM. An assessment of adult's perceptions of their psychological, physical and social age. J Clin Gerops 1996;2:117–128. [ Links ]

14. Webster J, Tiggemann M. The relationship between women's body dissatisfaction and self–image across the life span: the role of cognitive control. J Genet Psychology 2003;164:241–251. [ Links ]

15. Feingold A, Mazzela R. Gender differences in body image are increasing. Psychol Sci 1998;9:190–195. [ Links ]

16. Janelli LM. Are there body image differences between older men and women? West J Nurs Res 1993;15:327–339. [ Links ]

17. Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta–analytic review. Psychol Bull 2002;128:825–848. [ Links ]

18. Dittmar H. Vulnerability factors and processes linking sociocultural pressures and body dissatisfaction. J Soc Clin Psy 2005;24(8):1081–1087. [ Links ]

19. Vignoles V, Deas C. Appearance–related negative health behaviours and identity motives. Paper presented at the meeting of the British Psychological Society, Social Psychology Section Annual Conference. Huddersfield, UK; 2002. [ Links ]

20. Rozin P, Fallon A. Body image, attitudes to weight and misperceptions of figure preferences of the opposite sex: a comparison of men and women in two generations. J Abnorm Psychol 1988;97:342–345. [ Links ]

21. Tunaley JR, Walsh S, Nicolson P. <<I'm not bad for my age:>> the meaning of body size and eating in the lives of older women. Aging Soc 1999;19:741–759. [ Links ]

22. Warren CS, Gleaves DH, Cepeda–Benito A, Fernández MC, Rodríguez–Ruiz S. Ethnicity as a protective factor against internalization of a thin ideal and body dissatisfaction. Int J Eat Dis 2005;37(3):241–249. [ Links ]

23. Harrison K. The body electric: thin–ideal media, self–discrepancies, and eating disorder symptomatology in adolescents. J Soc and Clin Psyc 2000;20:289–323. [ Links ]

24. Garner DM. EDI–2. Eating Disorder Inventory–2. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources. (Spanish translation S Corral, M González, J Pereña, N Seisdedos). Madrid: TEA; 1990. [ Links ]

25. Toro J, Salamero M, Martínez–Mallén E. Assessment of sociocultural influences on the aesthetic body shape model in anorexia nervosa. Act Psych Scandic 1994;89:147–151. [ Links ]

26. Tiggemann M. Body–size dissatisfaction: individual differences in age and gender, and relationship with self–esteem. Person In Diff 1992;13:39–43. [ Links ]

27. Vázquez R, Álvarez G, Mancilla JM. Consistencia interna y estructura factorial del Cuestionario de Influencia de los Modelos Estéticos Corporales (CIMEC) en población mexicana. Salud Mental 2000;23(6):18–24. [ Links ]

28. Altabe M, Thompson, JK. Body Image Changes During Early Adulthood. Int J Eat Disord 1993;13(3):323–328. [ Links ]

29. Garner DM. The 1997 body image survey results. Psycho Today 1997;30:30–46. [ Links ]

30. Thompson SC, Thomas C, Rickabaugh CA, Tantamjarik P, Otsuki T et al. Primary and secondary control over age–related changes in physical appearance. J Pers 998;66:583–605. [ Links ]

31. Palladino–Green S, Pritchard ME. Predictors of body image dissatisfaction in adult men and women. Soc Beh Pers 2003;31(3):215–222. [ Links ]

32. Tiggemann M. Media exposure, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: television and magazines are not the same. Eur Eat Dis Rev 2003;11(5):418–430. [ Links ]

33. Tiggemann M, Pickering AS. Role of television in adolescent women's body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. Int J Eat Dis 1996;20:199–203. [ Links ]

34. Groesz LM, Levine MP, Murnen SK. The effects of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: a meta–analytic review. Int J Eat Dis 2002;31(1):1–16. [ Links ]

35. Harrison K, Cantor J. The relationship between media consumption and eating disorders. J Commun 1997;47:40–67. [ Links ]

36. Levine MP, Smolak L, Hayden H. The relation of sociocultural factors to eating attitudes and behaviors among middle school girls. J Early Adolesc 1994;14(4):471–490. [ Links ]

37. Agliata D, Tantleff–Dunn S. The impact of media exposure on males body image. J Soc Clin Psych 2004;23(1):7–22. [ Links ]