Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de fitopatología

On-line version ISSN 2007-8080Print version ISSN 0185-3309

Rev. mex. fitopatol vol.39 n.2 Texcoco May. 2021 Epub Nov 03, 2021

https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.2011-1

Phytopathological notes

Fungi associated with common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) wilt in Costa Rica

1 Centro de Investigación en Protección de Cultivos y Centro de Investigaciones en Estructuras Microscópicas, Escuela de Agronomía, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San José, Costa Rica;

2 Programa de Leguminosas, Estación Experimental Agrícola Fabio Baudrit, Universidad de Costa Rica. 183-4050 Alajuela, Costa Rica;

3 Centro de Investigaciones en Productos Naturales (CIPRONA) y Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, 11501-2060, San José, Costa Rica y Department of Plant Sciences and Landscape Architecture, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, 20742, U.S.A.;

4 Instituto Nacional de Innovación y Transferencia en Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA), 382-1007 Centro Colón, Costa Rica;

Root rot limits the performance of beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), and although they are frequent in Costa Rica, the identity of the fungi associated with them is uncertain. The objective of this research was to molecularly identify the fungi associated with root rot and wilt of beans in the two main producing areas of the country. Between 2017 and 2020, 120 plants were collected in 20 farms in the Huetar Norte and Brunca regions. Experimental lines (IBC 302-29 and ALS 0536-6) and commercial varieties (Brunca, Cabécar, Chánguena, Guaymí, Nambí and Tayní) were sampled. The symptoms observed in the field were described and isolates were made on chloramphenicol bengal rose water agar, then pure hypha-tip cultures on water agar, which were transferred to potato dextrose agar to determine morphotypes with the use of taxonomic keys. Isolated fungi were also identified by sequencing the ITS region of ribosomal nuclear DNA. The percentage of relative frequency of morphotypes was calculated. The most frequent were Macrophomina phaseolina (26.7%), Fusarium oxysporum (13.6%) and Athelia rolfsii (5.6%). From the wilt symptoms observed in the field, the fungi commonly described in beans for these pathologies were isolated. It is necessary to perform pathogenicity tests to confirm that they are the cause of the infections.

Key words: Soil-borne pathogens; Fusarium oxysporum; Macrophomina phaseolina; Athelia rolfsii

Las pudriciones radicales limitan el rendimiento del frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris), y aunque en Costa Rica son frecuentes, la identidad de los hongos asociados a ellas es incierta. El objetivo de esta investigación fue identificar molecularmente los hongos asociados a las pudriciones radicales y marchitez del frijol en las dos principales zonas productoras del país. Entre 2017 y 2020, se recolectaron 120 plantas en 20 fincas de las regiones Huetar Norte y Brunca. Se muestrearon líneas experimentales (IBC 302-29 y ALS 0536-6) y variedades comerciales (Brunca, Cabécar, Chánguena, Guaymí, Nambí y Tayní). Se describieron los síntomas observados en campo y se efectuaron aislamientos en agar agua rosa de bengala cloranfenicol, luego cultivos puros de punta de hifa en agar agua, que se trasfirieron a papa dextrosa agar para determinar morfotipos con el uso de claves taxonómicas. Los hongos aislados también se identificaron mediante secuenciación de la región ITS del ADN nuclear ribosomal. Se calculó el porcentaje de frecuencia relativa de morfotipos. Los más frecuentes fueron Macrophomina phaseolina (26.7%), Fusarium oxysporum (13.6%) y Athelia rolfsii (5.6%). A partir de los síntomas de marchitez observados en campo se aislaron los hongos comúnmente descritos en frijol para esas patologías. Es necesario realizar pruebas de patogenicidad para confirmar que son los agentes causales.

Palabras clave: Patógenos de la raíz; Fusarium oxysporum; Macrophomina phaseolina; Athelia rolfsii

Beans are consumed by 97% of the Costa Rican population, and are a crucial grain for food and nutritional security, and its production is mainly in the hands of small-scale farmers (<5 ha) (Hernández-Fonseca, 2009; Rodríguez-González and Fernández-Rojas, 2015). The crop faces a series of limitations, such as diseases, which may reduce its productivity significantly (Schoonhoven and Voysest, 1994). Among these diseases, root pathogens such as Macrophomina phaseolina, Rhizoctonia solani, Fusarium sp. and Pythium sp. have the potential to produce losses of 80 to 100% of the yield (Singh and Schwartz, 2010; Méndez-Aguilar et al., 2013).

The most efficient way to manage pathological problems, and particularly soil diseases, is trough the of resistant cultivars (Mendes et al., 2019). Since 1995, in Costa Rica the methodology of participative plant breeding has been used, helping generate varieties with a greater resistance to biotic and abiotic problems, higher productivity and better adapted to conditions of small-scale farming (Hernández et al., 2018).

The change in the use of commercial varieties, climate change and the incorporation of new production areas have benefitted the progress of root rot epidemics in Costa Rica related mainly to Fusarium solani f. sp. phaseoli, Athelia rolfsii (sin. Sclerotium rolfsii) and Macrophomina phaseolina (Araya and Hernández, 2003; Araya and Hernández, 2006). However, the presence of such causal agents has not been proven and existing publications are based only on the comparison of field symptoms with those reported in literature; there are no references of isolations or identification at a molecular level. Due to this, the aim of the present investigation was to identify, both morphologically and molecularly, the fungi associated with root rot and wilting of common bean plants in the main production areas of Costa Rica.

For this investigation, 120 plants in different phenological stages were sampled (from seedlings to plants in filling of pods), distributed into eight farms of the region of Brunca (2017 and 2018) in southeastern Costa Rica, and 12 from the region of Norte (2019 and 2020), in the north of the country. Samples were taken in fields of the experimental lines ALS 0536-6 and IBC 302-29, as well as of the commercial varieties Brunca, Cabécar, Chánguena, Guaymí, Nambí and Tayní (Hernández-Fonseca and Araya-Villalobos, 2009; Hernández-Fonseca and Chaves-Barrantes, 2016).

Three plants with symptoms and three asymptomatic plants were taken from each farm. Asymptomatic plants were collected to isolate endophytic fungi with possible antagonistic abilities. Sections of tissue were taken and washed with soap and water, and were later disinfected with alcohol at 70% for 1 min and isolations were performed with chloramphenicol bengal rose water agar culture medium, and incubated for seven days in the dark, between 23 and 25 °C. This was followed by pure hypha-tip cultures on water agar 30 g L-1 (3%), and the identification of morphotypes in potato-dextrose-agar (PDA), following descriptions by Leslie and Summerell (2006) and Seifert et al. (2011). Using these data, the percentage of relative frequency (%FR) was calculated following Mueller et al. (2004), using the formula: %FR = (number of isolations of each species/total number of species) x 100. The most frequent were selected to carry out molecular identification.

The DNA was extracted using the Prepman Ultra kit and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out using primers ITS-5 (GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG) and ITS-4 (TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) of the region of the internal transcribed spacer of the nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA ITS) (Schoch et al., 2012). A PCR reaction (25 µL) was prepared following White et al. (1990), and the products were sent to Macrogen (USA) for purification and sequencing. The sequences obtained were edited and aligned with the use of Geneious, version 10.2.3 and compared with those available in the GenBank using the algorithm BLASTn. A species identification was considered as positive when the sequences had a similarity of 100 %, as a possible species if it obtained 99% (suffix cf. was written), and as a related species if it obtained 96 to 98% (suffix aff. was written) (Hofstetter et al., 2019). For the range of the genus, a similarity of 97% was considered (López et al., 2017).

The 155 isolations recovered from symptomatic and asymptomatic plants were classified into nine morphotypes (Figure 1). The fungi with the highest percentage of relative frequency were M. phaseolina (26.7), F. oxysporum (13.6) and A. rolfsii (5.6).

The recovered fungi varied according to the year and region of sampling. For example, A. rolfsii was recovered on all four years of sampling in both regions, whereas M. phaseolina was only isolated in 2019 in the region of Huetar Norte (Table 1).

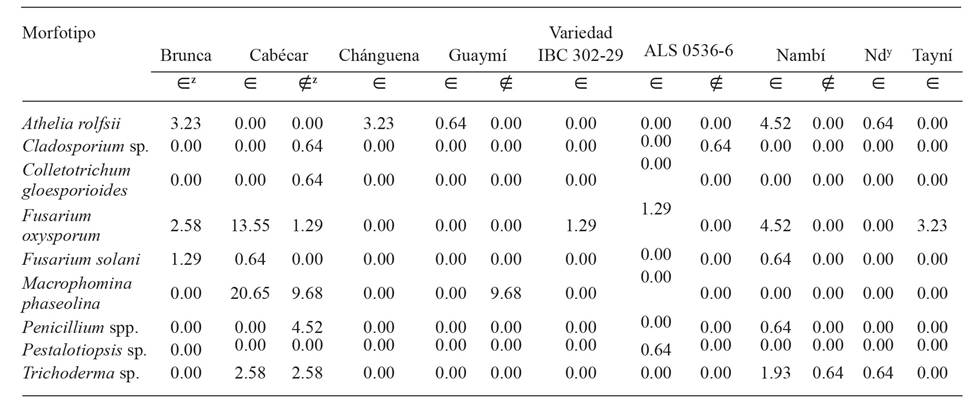

In plants with symptoms of wilting, M. phaseolina and F. oxysporum were isolated more frequently in the variety Cabécar, while A. rolfsii was found most often in the varieties Nambí, Brunca and Chánguena (Table 2). In general, F. oxysporum, F. solani and A. rolfsii were found as fungi related to plants with problems of wilting in almost all commercial varieties and experimental lines sampled.

The sequencing of the ITS region showed that the Fusarium morphotypes were located in the operative taxonomic units F. fujikuroi, F. solani and F. oxysporum. The fungus classified preliminarily as M. phaseolina had a percentage of similarity of 100%. The isolations tentatively defined as Penicillium spp. were classified as P. crustosum, P. simplicissimum, Penicillium sp. and Talaromyces pinophilus (Table 3). No DNA from A. rolfsii was sequenced, since its morphological characteristics were enough to identify it, and they coincided with those described by Kamil et al. (2020): cottonlike white mycelium with clamp connections in both plant and PDA culture medium and the development of spherical sclerotia, approximately 1 mm in size, colored white at the beginning and light brown at maturity.

Figure 1 Relative frequency (%) of morphotypes of fungi isolated from common bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris) in the regions of Huetar Norte and Brunca, Costa Rica during the years 2017-2020.

x Region of production; y Year; z∈ : plants with symptoms, ∉ : symptomatic plants

Table 1 Relative frequency (%) of morphotypes by region of production, year collected and state (with symp toms/asymptomatic) of the common bean plant (Phaseolus vulgaris). Costa Rica. Year 2017-2020.

z∈ : plants with symptoms, ∉ : asymptomatic plants, Nd: no data, the variety is not know.

Table 2 Relative frequency (%) of morphotypes by variety of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), recovered from plants with and without symptoms of wilting. Regions of Huetar Norte and Brunca, Costa Rica. Years 2017-2020.

The species with the highest frequency of isolation, M. phaseolina, F. oxysporum and A. rolfsii (Figure 1), are related to root rot and vascular wilting in common bean plants worldwide (Xue et al., 2015; Yesil and Bastas, 2016; Al-Jaradi et al., 2018; Sendi et al., 2019). In Costa Rica they were reported previously (Echandi, 1967; Araya and Hernández, 2003; Villalobos et al., 2009); however, in no previous investigation was there a morphological identification or any molecular analysis to confirm the identity of the pathogenic agent related to the damage described.

Table 3 Molecular identification, percentage of similarity, accession and length of the ITS sequence of morphotypes recov ered from common bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris) with and without symptoms of wilting, depending on the region of production and the variety. Regions of Huetar Norte and Brunca, Costa Rica. 2017-2020.

| Identificación | % de similitud | Secuencias de referencia disponibles en GenBank | # accesión en GenBank | Longitud de la secuencia (pares de bases) | Región productora | Variedad | Estado de la planta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fusarium cf. fujikuroi | 99.8 | KT192406 | MW449097 | 514 | Brunca | IBC302-29 | Con síntoma |

| Fusarium cf. oxysporum | 99.5 | MK156682 | MW449096 | 503 | Brunca | ALS 0536-6 | Con síntoma |

| Fusarium cf. solani | 99.9 | MK817031 | MW449094 | 503 | Brunca | Cabécar | Con síntoma |

| Macrophomina phaseolina | 100.0 | MK968305 | MW449091 | 536 | Huetar Norte | Guaymí | Con síntoma |

| Colletotrichum sp. | 99.6 | KX721643 | MW449095 | 515 | Brunca | Cabécar | Sin síntoma |

| Penicillium aff. crustosum | 98.3 | KF938410 | MW449099 | 489 | Brunca | Cabécar | Sin síntoma |

| Penicillium cf. simplicissimum | 99.7 | KM104597 | MW449100 | 490 | Brunca | Cabécar | Sin síntoma |

| Penicillium sp. | 100.0 | KY552262 | MW449093 | 537 | Brunca | Nambí | Sin síntoma |

| Talaromyces cf. pinophilus | 99.5 | CP017345 | MW449092 | 527 | Brunca | Cabécar | Sin síntoma |

| Trichoderma cf. harzianum | 99.7 | MK387946 | MW449098 | 550 | Brunca | Nambí | Sin síntoma |

The symptoms observed on the field for symptoms of carbon rot caused by M. phaseolina coincided with those reported for Sun et al. (2019) for this pathology and included chlorosis, wilting and the death of adult plants with completely dehydrated leaves attached to the stem (Figure 2 A and D), as well as discoloration and rotting on the base of the stem. According to Araya and Hernández (2003), this species is commonly found in the region of Huetar Norte, but not in the region of Brunca, a behavior which was also displayed in this study (Table 1).

During the 2019 productive cycle, the region of Huetar had drought conditions and high temperatures, typical of a year under the influence of El Niño (Fernández and Ramírez, 1991; Alvarado, 2019), which favored or predisposed infection with M. phaseolina (Dhingra and Chagas, 1981), due to the physiological alterations undergone by the host, such as a reduction in the transpiration rate and stomatal conductance (Mayek-Pérez et al., 2002). These conditions would explain why, in that year alone, it was possible to recover this pathogen from wilted plants in the region and in the other sampling years it was not isolated. In this regard, 2018 had rain conditions, typical of a year under the influence of the La Niña phenomenon (Fernández and Ramírez, 1991; Alvarado, 2018) and 2017 and 2020 were neutral years, according to the National Weather Institute of Costa Rica (Alvarado, 2017; Alvarado, 2020).

On the other hand, F. oxysporum was isolated from seedlings and adult plants with long and sunken lesions and reddish in color (Figure 2 B and E). The symptoms on the field were distributed in patches, although they were occasionally found at random. The damages observed agreed with those indicated for wilting by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli (Fop) in several investigations: plants with delayed growth, gradual yellowing, defoliation and discoloration of vascular tissues in roots and stems (Kendrick and Snyder, 1942; Schwartz, 1989; Saremi et al., 2011; Edel-Hermann and Lecomte, 2019). Wilting by Fop is considered one of the main diseases in common bean plants worldwide (Xue et al., 2015).

Figure 2 Common bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris) with signs of wilting, from which A) and D) Macrophomina phaseolina; B) and E) Fusarium oxysporum; C) and F) Athelia rolfsii were isolated. Regions of Brunca and Huetar Norte, Costa Rica. 2018-2020.

Both Macrophomina and Fusarium can be transmitted by seeds. The latter can be found on the surface and underneath it, particularly in the cotyledons (Kendrick, 1934; Singh and Schwartz, 2010; Marcenaro and Valkonen, 2016). In this study, these pathogens were isolated from asymptomatic plants, which may indicate that they are latent in the seeds, as in findings by Parsa et al. (2016), who found both fungi in an endophytic form in healthy and disinfected seeds.

The diseased caused by Athelia rolfsii in the bean plant is known worldwide as southern blight, and its symptoms include wilting and lesions on the base of the plant, which gradually dry it out. Additionally, a development of thick, white, cottonlike mycelia frequently appears in the lesion, along with brown, spherical sclerotia (Abawi and Pastor-Corrales, 1990; Mahadevakumar et al., 2015), all of which are symptoms and signs observed in this investigation (Figure 2 C and F). Athelia rolfsii was only obtained from adult plants with a complete collapse and, as in the case of Fusarium, it displayed aggregated distribution.

From the symptoms observed on the field, we isolated the fungi described in beans for those pathologies. However, pathogenicity tests must be performed to confirm that they are the cause of the infections. In addition, a more accurate molecular identification is necessary, with markers such as EF-1α, rpb2 and the gene of β-tubulin, especially in the genera Fusarium, Trichoderma and Talaromyces, to find exactly what species or special forms are present. This is particularly true when considering the findings by Marcenaro and Valkonen (2016), Edel-Hermann and Lecomte (2019) and Guido-Monge (2020), who reported the presence of other species of Fusarium related to the common bean; as well as reports by Otadoh (2011), Carvalho et al. (2014) and Abdel-Rahim and Abo-Elyousr (2018), who point out that Trichoderma and Talaromyces may be biocontrol agents.

The advanced commercial varieties and experimental lines sampled were susceptible to these pathogens. Due to their potential to cause losses in yields (Singh and Schwartz, 2010), the genetic breeding program for bean in Costa Rica must pay more attention to these pathologies.

This investigation corroborated, through isolation and molecular identification based on ITS, the identity of the fungi related to the wilting of bean plants in the main areas of production in Costa Rica, which helps develop better strategies to manage these pathogens. We suggest performing pathogenicity tests and molecular identification with markers such as EF-1α, rpb2 and the β-tubulin gene.

Acknowledgements

To the Foundation for the Promotion of Research and Transfer of Agricultural Technology of Costa Rica (FITTACORI), project F14-17, and the Vice-rectory of Research of the University of Costa Rica (UCR), project B7514, for the partial funding of this investigation; to the Research Center in Crops Protection (UCR) for allowing the use of the Phytopathology Laboratory facilities, and to Ing. Álvaro Ulate Hernández of the National Seed Office, for his help in the recollection of samples.

REFERENCES

Abawi GS and Pastor-Corrales MA. 1990. Root rots of beans in Latin America and Africa: diagnosis, research methodologies, and management strategies. CIAT. Cali, Colombia. 114 p. https://books.google.ca/books?id=YxGqzlSYtcMC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&hl=es#v=onepage&q&f=false [ Links ]

Abdel-Rahim IR and Abo-Elyousr KAM. 2018. Talaromyces pinophilus strain AUN-1 as a novel mycoparasite of Botrytis cinerea, the pathogen of onion scape and umbel blights. Microbiological Research 212-213:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2018.04.004 [ Links ]

Al-Jaradi A, Al-Mahmooli I, Janke R, Maharachchikumbura S, Al-Saady N and Al-Sadi AM. 2018. Isolation and identification of pathogenic fungi and oomycetes associated with beans and cowpea root diseases in Oman. PeerJ-Life and Environment 6: e6064. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6064 [ Links ]

Alvarado, LF. 2017. Informe 10. Boletín del ENOS No. 101. Fase actual: Neutra. Instituto Meteorológico Nacional de Costa Rica (IMN). San José, Costa Rica. 2p. https://www.imn.ac.cr/documents/10179/431236/%23%20101 [ Links ]

Alvarado, LF. 2018. Informe 3. Boletín del ENOS No. 112. Fase actual: La Niña. Instituto Meteorológico Nacional de Costa Rica (IMN). San José, Costa Rica. 4p. https://www.imn.ac.cr/documents/10179/450551/%23%20112 [ Links ]

Alvarado, LF. 2019. Informe 10. Boletín del ENOS No. 119. Fase actual: El Niño. Instituto Meteorológico Nacional de Costa Rica (IMN). San José, Costa Rica. 5p. https://www.imn.ac.cr/documents/10179/470467/%23119 [ Links ]

Alvarado, LF. 2020. Informe marzo 2020. Boletín del ENOS No. 129. Fase actual: Neutra. Instituto Meteorológico Nacional de Costa Rica (IMN). San José, Costa Rica . 2p. https://www.imn.ac.cr/documents/10179/486374/%23129 [ Links ]

Araya CM y Hernández JC. 2003. Distribución agroecológica de enfermedades del frijol en Costa Rica. Manejo Integrado de Plagas y Agroecología (Costa Rica) 68: 26-33. http://hdl.handle.net/11554/6067 [ Links ]

Araya CM y Hernández JC. 2006. Guía para la identificación de las enfermedades del frijol más comunes en Costa Rica. Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería (MAG). San José, Costa Rica. 44p. http://www.mag.go.cr/bibliotecavirtual/H20-5247.pdf [ Links ]

Carvalho DC, Lobo-Junior M, Martins I, Inglis PW and Mello SCM. 2014. Biological control of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli by Trichoderma harzianum and its use for common bean seed treatment. Tropical Plant Pathology 39(5): 384-391. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1982-56762014000500005 [ Links ]

Dhingra OD and Chagas D. 1981. Effect of soil temperature, moisture, and nitrogen on competitive saprophytic ability of Macrophomina phaseolina. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 77(1): 15-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0007-1536(81)80173-8 [ Links ]

Echandi E. 1967. Amarillamiento del frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) provocado por Fusarium oxysporum f. phaseoli. Turrialba 17(4): 409-411. [ Links ]

Edel-Hermann V and Lecomte C. 2019. Current status of Fusarium oxysporum formae speciales and races. Phytopathology 109(4): 512-530. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-08-18-0320-RVW [ Links ]

Fernández W y Ramírez P. 1991. El Niño, la Oscilación del Sur y sus efectos en Costa Rica: una revisión. Tecnología en Marcha 11(1): 3-10. https://revistas.tec.ac.cr/index.php/tec_marcha/article/view/2631 [ Links ]

Guido-Monge, AZ. 2020. Prevalencia de especies micotoxigénicas de Fusarium en frijol negro producido en Costa Rica y determinación de su capacidad toxigénica. [Tesis de Licenciatura sin publicar]. Universidad de Costa Rica. [ Links ]

Hernández-Fonseca JC. 2009. Zonas de cultivo y épocas de siembra. Pp:18. In: Hernández JC y Ramírez L (eds.). Cultivo de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris). Manual de recomendaciones técnicas para el cultivo de frijol. Instituto Nacional de Innovación y Transferencia en Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA). San José, Costa Rica. 80p. http://www.mag.go.cr/bibliotecavirtual/F01-9533.pdf [ Links ]

Hernández-Fonseca JC y Araya-Villalobos R. 2009. Cultivo. Pp:19-26. In: Hernández JC y Ramírez L (eds.). Cultivo de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris). Manual de recomendaciones técnicas para el cultivo de frijol. Instituto Nacional de Innovación y Transferencia en Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA). San José, Costa Rica. 80p. http://www.mag.go.cr/bibliotecavirtual/F01-9533.pdf [ Links ]

Hernández-Fonseca JC y Chaves-Barrantes N. 2016. Nambí. Variedad de frijol resistente a la sequía terminal. Instituto Nacional de Innovación y Transferencia en Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA) y Estación Experimental Agrícola Fabio Baudrit Moreno, Universidad de Costa. Alajuela, Costa Rica. Plegable. 6p. [ Links ]

Hernández JC, Chaves NF, Araya R y Beebe S. 2018. “Diquís”, variedad de frijol común rojo brillante. Agronomía Costarricense 42(1): 127-136. http://www.mag.go.cr/rev_agr/v42n01_127.pdf [ Links ]

Hofstetter V, Buyck B, Eyssartier G, Schnee S and Gindro K. 2019. The unbearable lightness of sequenced-based identification. Fungal Diversity 96: 243-284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-019-00428-3 [ Links ]

Kamil D, Bahadur A, Debnath P, Kumari A, Choudhary SP and Prameeladevi T. 2020. First report of Athelia rolfsii causing stem rot disease on Vasaka (Justicia adhatoda). Australasian Plant Disease Notes 15(1): 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13314-020-00402-y [ Links ]

Kendrick JB. 1934. Seed transmition of fusarium yellows of beans. Phytopathology 24(10): 1139. [ Links ]

Kendrick JB and Snyder WC. 1942. Fusarium yellows of beans. Phytopathology 32(11): 1010-1014. [ Links ]

Leslie JF and Summerell BA. 2006. Morphological characters. Pp:111-119. In: Leslie JF and Summerell BA. (eds.). The Fusarium laboratory manual. Blackwell Publishing. Iowa, USA. 388p. [ Links ]

López R, Gómez S, De la Rosa S and Garrido E. 2017. The age of lima bean leaves influences the richness and diversity of the endophytic fungal community, but not the antagonistic effect of endophytes against Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. Fungal Ecology 26: 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funeco.2016.11.004 [ Links ]

Mahadevakumar S, Tejaswini GS, Janardhana GR and Yadav V. 2015. First report of Sclerotium rolfsii causing southern blight and leaf spot on common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) in India. Plant Disease 99(9): 1280-1280. https://doi.org/10.1094/pdis-01-15-0125-pdn [ Links ]

Marcenaro D and Valkonen JPT. 2016. Seedborne pathogenic fungi in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris cv. INTA Rojo) in Nicaragua. PLOS ONE 11(12): e0168662. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168662 [ Links ]

Mayek-Pérez N, García-Espinosa R, López-Castañeda C, Acosta-Gallegos JA and Simpson J. 2002. Water relations, histopathology and growth of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) during pathogenesis of Macrophomina phaseolina under drought stress. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 60(4): 185-195. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmpp.2001.0388 [ Links ]

Mendes LW, de Chaves MG, Fonseca MC, Mendes R, Raaijmakers JM and Tsai SM. 2019. Resistance breeding of common bean shapes the physiology of the rhizosphere microbiome. Frontiers in Microbiology 10: 2252. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02252 [ Links ]

Méndez-Aguilar R, Reyes-Valdés MH y Mayek-Pérez N. 2013. Avances y perspectivas sobre el mapeo genético de la resistencia a las pudriciones de la raíz en frijol común. Phyton 82:215-226.http://www.revistaphyton.fund-romuloraggio.org.ar/vol82/MENDEZ_AGUILAR.pdf [ Links ]

Mueller G, Bills G and Foster M. 2004. Biodiversity of fungi. Inventory and monitoring methods. Elsevier Academic Press. London, UK. 777p. [ Links ]

Otadoh JA, Okoth SA, Ochanda J and Kahindi JP. 2011. Assessment of Trichoderma isolates for virulence efficacy on Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli. Tropical and subtropical agroecosystems 13(1): 99-107. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/tsa/v13n1/v13n1a15.pdf [ Links ]

Parsa S, García-Lemos AM, Castillo K, Ortiz V, López-Lavalle LAB, Braun J and Vega FE. 2016. Fungal endophytes in germinated seeds of the common bean, Phaseolus vulgaris. Fungal Biology 120(5): 783-790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2016.01.017 [ Links ]

Rodríguez-González S y Fernández-Rojas SE. 2015. Prácticas culinarias asociadas al consumo de frijoles en familias costarricenses. Agronomía Mesoamericana 26(1): 145-151. https://doi.org/10.15517/am.v26i1.16937 [ Links ]

Saremi H, Amiri ME and Ashrafi J. 2011. Epidemiological aspects of bean decline disease caused by Fusarium species and evaluation of the bean resistant cultivars to disease in Northwest Iran. African Journal of Biotechnology 10(66): 14954-14961. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB11.258 [ Links ]

Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Huhndorf S, Robert V, Spouge JL, Levesque CA, Chen W and Fungal Barcoding Consoirtium. 2012. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(16): 6241-6246. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117018109 [ Links ]

Schoonhoven A y Voysest O. 1994. El frijol común en América Latina y sus limitaciones. Pp:39-66. In: Pastor-Corrales M y Schwartz HF (eds.). Problemas de producción del frijol en los trópicos. 2 ed. Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT). Cali, Colombia. 805p. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/132664941.pdf [ Links ]

Seifert K, Morgan-Jones G, Gams W and Kendrick B. 2011. The genera of Hyphomycetes. CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre. Utrecht, The Netherlands. 997 p. [ Links ]

Sendi Y, Romdhane SB, Mhamdi R and Mrabet M. 2019. Diversity and geographic distribution of fungal strains infecting field-grown common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Tunisia. European Journal of Plant Pathology 153(3):947-955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-018-01612-y [ Links ]

Singh SP and Schwartz HF. 2010 Breeding common bean for resistance to diseases: a review. Crop Science 50:2199-2223. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2009.03.0163 [ Links ]

Sun SL, Zhu ZD, Duan CX, Zhao P, Sun F, Deng D and He YH. 2019. First report of charcoal rot caused by Macrophomina phaseolina on faba bean in China. Plant Disease 103(6): 1415. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-09-18-1660-PDN [ Links ]

Schwartz HF. 1989. Occurrence of fusarium wilt of beans in Colorado. Plant Disease 73(6): 518. https://doi.org/10.1094/PD-73-0518D. [ Links ]

Villalobos JL, Cárdenas FA y Cordero JM. 2009. Lista de enfermedades de los cultivos agrícolas y forestales de Costa Rica. Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería. Servicio Fitosanitario del Estado. Diagnóstico Fitosanitario. San José, Costa Rica. 118 p. [ Links ]

White T, Bruns S y Taylor J. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. Pp: 315-322. In: Innis M, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ y White TJ (eds) PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press, Inc., New York. 482p. [ Links ]

Xue R, Wu J, Zhu Z, Wang L, Wang X, Wang S and Blair MW. 2015. Differentially expressed genes in resistant and susceptible common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes in response to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli. PLOS ONE 10(6): e0127698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127698 [ Links ]

Yesil S and Bastas KK. 2016. Genetic variability of Macrophomina phaseolina isolates from dry beans in Turkey. Turkish Journal of Agriculture - Food Science and Technology 4(4):305. https://doi.org/10.24925/turjaf.v4i4.305-312.572 [ Links ]

Received: November 11, 2020; Accepted: February 17, 2021

text in

text in