Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de fitopatología

versão On-line ISSN 2007-8080versão impressa ISSN 0185-3309

Rev. mex. fitopatol vol.38 no.2 Texcoco Mai. 2020 Epub 27-Nov-2020

https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.2002-4

Scientific Articles

Pathogenic fungi associated to commercial seed of mexican varieties of Bouteloua curtipendula

1 Colegio de Postgraduados, Km 36.5 Carretera México-Texcoco, Montecillo, Estado de México, México. CP 56230;

2 Servicio Nacional de Sanidad, Inocuidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria-SENASICA, Km 37.5 Carretera México-Pachuca, Tecámac, Estado de México, México. CP 55740;

Plant seeds represent a main source for pathogen dissemination; in order to determine pathogens associated with propagules of five varieties of sideoats gramma: NdeM-La Zarca, NdeM-303, NdeM-5, NdeM-Zenith, NdeM-La resolana, three different kind of propagules were analyzed, from seed (spikelets) available from commercial production fields located at Valle del Mezquital, Hidalgo: spikelets (caryopsis + accessory bracts; M1), caryopsis + lemma (M2) and pure caryopsis (M3). Seed was harvested during 2017. In order to promote the expression of fungus growth already present on the propagule, spikelets (M1) were sown within a humidity chamber; while M2 and M3, sown on PDA culture media (five propagules per Petri dish, 60 dishes per variety); growth material was later sown on specific media for identification. Isolated results were identified through growth traits on culture media, morphology traits and molecular markers. Alternaria alternata y A. tenuissima was observed for 67% of the samples, Fusarium scirpi and F. incarnatum, at 24%, and Bipolaris cynodontis, in 9%. To date, none of these pathogenic species have been reported in Mexico for commercial seed of B. curtipendula. These findings open a wide spectrum for sanitary management of produced seed for this plant species.

Key words: sideoats gramma; seed health; seed quality

La semilla es una importante forma de diseminación de patógenos; para determinar aquellos asociados a semilla comercial de variedades de pasto Banderita: NdeM-La Zarca, NdeM-303, NdeM-5, NdeM-Zenith, NdeM-La resolana, se analizaron tres tipos de propágulo: espiguillas completas (cariópside + brácteas accesorias; M1), cariópside únicamente con lemas (M2) y cariópsides limpios (M3), provenientes de lotes del Valle del Mezquital, Hidalgo, cosechados en 2017. Para promover el desarrollo de hongos, se sembraron espiguillas (M1) en cámara de humedad; mientras que M2 y M3 fueron sembradas en medio PDA (cinco propágulos por caja Petri y 60 cajas por variedad); posteriormente, los crecimientos se aislaron en medios selectivos. Los aislados se identificaron por características del cultivo, morfológicas y moleculares. Se obtuvieron 51 aislamientos en los tres tipos de propágulo y variedades; los cuales, se asociaron a Alternaria alternata y A. tenuissima (67% de frecuencia), Fusarium scirpi y F. incarnatum (24%) y Bipolaris cynodontis (9%). Ninguna de estas especies ha sido reportada anteriormente en México para semilla comercial de B. curtipendula. Con lo anterior, se abre un panorama de opciones para futuros estudios de patogenicidad de los hongos aislados y en consecuencia el manejo sanitario de la semilla producida.

Palabras clave: Banderita; calidad de semilla; sanidad de semilla

Seed is the major form (sexual and asexual) of crop dissemination. Seeds carry genetic and morphological traits that are essential for livestock and agricultural production. However, seeds can also carry pathogenic organisms, which can affect production efficiency (Arriagada, 2012; Lamichhane et al., 2020). The negative effect of the seed-pathogen association can limit plant density, raw materials, food, and seriously affect both human and animal health (Afzal et al., 2019). Seed inspection and analysis allow the timely detection of the causal pathogens thus providing the opportunity to take management measures. Among the pathogens associated with seed of fodder grass species, fungi are the most important because, in addition to affecting plant density at establishment and yield due to diseases, they also alter crop parameters, including stem lignification, lower digestibility, free amino acid content in roots and leaves of the affected plants, mycotoxins that cause livestock diseases, among other problems (Pirelli et al., 2016). Plant health along with other variables (viability, germination, purity and vigor) determine the quality of a seed lot. Most of the specialized literature indicates that fungi genera such as Alternaria, Aspergillus, Botrytis, Cladosporium, Curvularia, Doratomyces, Fusarium, Helminthosporium, Macrophomina, Nigrospora, Penicillium, Chaetomium, Pestalotia and Rhizopus, include species associated with seed, in the field and in the warehouse (Lezcano et al., 2007). The benefits of seed with good sanitary control against airborne and soil pathogens include better emergence, plant height and vigor, as well as greater aerial and root biomass (Lamichhane et al., 2020).

In Mexico, nearly 90% of fodder grass species seeds is imported (Quero et al., 2017). The need for national genetic resources for forage species that guarantee quality, high persistence and adaptation to specific regional conditions (Quero et al., 2007), makes it necessary to conduct studies on seed produced in Mexico to assure sanitary, genetic and commercial quality, and to promote the recovery of the national market with seed of best quality. The establishment of high-risk prairies under semiarid rainfed areas implies management with high uncertainty due to the climate and where the biological and sanitary quality of seed is, most of the time, the only component that can be managed with certainty (Quero-Carrillo et al., 2014). Sideoats gramma (Bouteloua curtipendula) is a species native to Mexico’s arid and semiarid areas showing good palatability for grazing cattle, has high nutritional quality and is in high demand for reseeding prairies and pasturelands in arid and semiarid areas (Morales et al., 2009). Therefore, the objective of the present study was to identify pathogenic fungi associated with sideoats gramma seed that is commercially produced in Valle del Mezquital, Hidalgo.

Materials And Methods

Genetic material. The evaluated varieties correspond to five apomictic genetic materials of sideoats gramma registered by Colegio de Postgraduados in 2017 and 2018, available for research at the Forages area of the Livestock Program. These novel varieties were evaluated for which information about their sanitary quality is not available: 1) “NdeM-La Zarca”; 2) “NdeM-303”; 3) “NdeM-5”; 4) “NdeM-Zenith”; and 5) “NdeM-La Resolana”. The seed was manually harvested (Autumn, 2017) in the middle of plots that are used only for commercial seed production and are irrigated with water from the Tula River, where no cattle are grazed, in sites that were established at least one year ago, with surfaces of one (NdeM-5, NdeM-Zenith; NdeM-La Resolana) and 10 ha (NdeM-La Zarca, NdeM-303), located in Valle del Mezquital, Hidalgo. Valle del Mezquital is located at 2000 masl and surrounded by northern and northeastern mountain ranges that keep humid air masses from the Gulf of Mexico from entering the valley. The weather is dry with summer rains classified as BSkwg and BShwg type. Annual rainfall is 500-600 mm. The minimum temperature is -10 °C in winter and the maximum 39.5 °C in summer (CONAGUA, 2018).

Fungi isolation and purification. The study was conducted in the Phytosanitary-Phytopathology Department of Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo-Texcoco Campus, State of Mexico, in 2018. The seeds of each variety were separated into three types of samples or propagules: M1-spikelets (accessory bracts + caryopses), M2-caryopsis with lemmas and clean M3-caryopsis (without accessory bracts). Each type of propagule (M1, M2 y M3) and variety was placed in 60 Petri dishes. The isolates were obtained: M1, not disinfested, using the blotting paper and freezing method (Warham et al., 1998). M2 and M3 were disinfested in a 1.5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 2 min, rinsed three times with sterile distilled water, dried with sterile absorbent paper, and five propagules per Petri dish were sown in Bioxon® PDA culture medium (potato-dextrose-agar; Crous et al., 2009). The Petri dishes were incubated at 24 ± 2 °C for 8 days or until structures were formed. Later, the necessary sub-cultivations were performed in PDA culture medium in order to proceed with the purification process using the hyphal tip and monosporic technique (Gilchrist et al., 2005). The following equation was used to calculate the isolation frequency per genus and type of sample: Frequency (%) = (Number of isolates of the identified genus/total of isolates analyzed by type of sample) *100 (Mariscal et al., 2017).

Morphological characterization. The obtained isolates were then sown in selective culture media according to the possible genera obtained by sowing the propagules. The Alternaria genus isolates were sown in petri dishes with PDA culture medium, V8 (Agar-vegetable juice®) and PCA (Potato-Carrot-Agar); the isolates of the Fusarium genus were sown in PDA culture medium, CLA (Carnation Agar) and SNA (Spezieller Nährstoffarmer-Agar); and, finally, isolates of the Bipolaris genus were sown in PDA culture medium only. The Petri dishes were incubated at 24 ± 2 °C temperature with 12 cycles of light/darkness for 14 days. Morphological identification was done based on the color of the colony, and the shape and size of the conidiophores and conidia. For Fusarium and Bipolaris, semi-permanent preparations were made in 50% glycerol. The sample size used for these measurements consisted of 50 specimens per genus (Crous et al., 2009) that were documented using a compound microscope with a Motic Images Plus 2.0 camera (Software Motic 580 ver.5.0.) and a Carl Zeiss® Imager D2 microscope with a camera (Axioncam 503 color). Identification was made based on taxonomic keys (Warham et al., 1998; Barnett and Hunter, 1972; Gilchrist et al., 2005; Leslie and Summerell, 2006; Manamgoda et al., 2014).

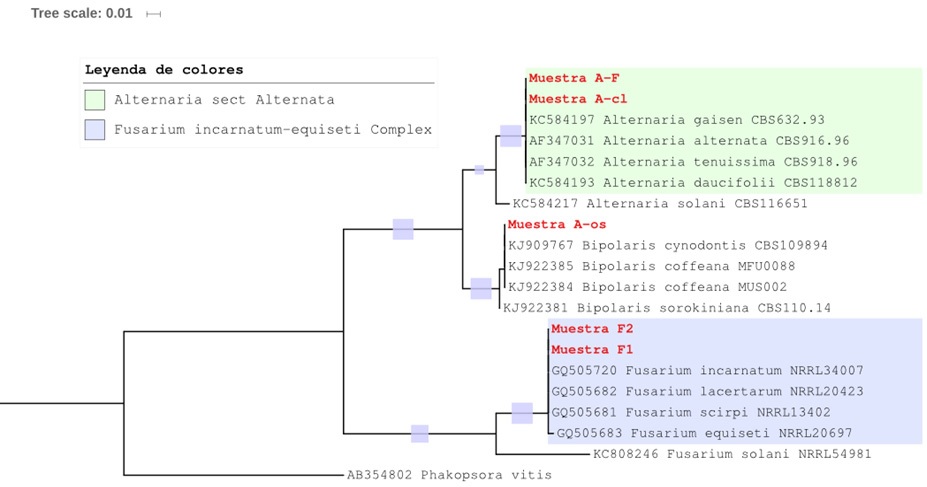

Molecular identification, sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis. To molecularly confirm the fungal species, genomic DNA was extracted using the alkaline phosphatase method (AP) (Sambrook and Russell, 2001) and its quality was evaluated using a Nanodrop. Then, samples were sent to Macrogen® Inc., Korea, for purification and DNA amplification through polymerase chain reaction (PCR). To do this, the ITS region of the ITS4 ribosomal DNA was amplified using the primer 5´-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3´ for Alternaria spp. and Bipolaris spp., which amplified a 550 bp fragment (White et al., 1990). For Fusarium spp., the ITS4 ribosomal DNA was used with the primer EF1-983F (5´- GCYCCYGGHCAYCGTGAYTTYAT-3´; Kidd et al., 2019) which amplified a 900-1,200 bp fragment. Both primers are considered universal and in the public domain. The sequences were edited and manually aligned with the BioEdit 7.2.5 software (Hall, 1999), and individually compared in the Gene Bank of the National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI), USA, using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) program with the pre-established parameters. The phylogenetic analysis of the multiple sequences was done using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA 7) software and the reference sequences reported by Woudenberg et al. (2013) for the genus Alternaria; by O´Donnell et al. (2009) for Fusarium, and by Manamgoda et al. 2014 for Bipolaris. All the sequences were aligned with the CLUSTAL-W algorithm and analyzed using the Neighbor-joining method (NJ) (Saitou and Nei, 1987). One thousand (1000) replications of support values (Bootstrap) were used to obtain a consensus tree with 70% majority rule (Tamura et al., 2004). The Phakopsora vitis basidiomycete was used as a root node, external to the group.

Results And Discussion

Among the 900 sowings of each variety (300 per type of propagule), the genera Alternaria, Bipolaris and Fusarium were the main fungi isolated from sideoats gramma propagules with variable incidence, depending on the type of propagule and variety. The Alternaria genus was identified with the greatest frequency (67%) among the five varieties and the three types of propagule, except for M3 (clean caryopse) of the NdeM-5 variety, from which this genus was not isolated because of the physical protection provided by the accessory bracts of this species, which delay or prevent pathogen penetration. At some stage of seed development, the bracts (glumes, lemma and palea) are solid and impermeable enough to keep the pathogen from reaching the caryopse. This fungus is widely distributed and present in the environment and can, from the soil, infest the seeds before and after harvest (Pavón et al., 2012). The seed can also be infested by coming in contact with contaminated bracts and/or because of poor seed management. This is important for seedling survival after sowing and not necessarily for fodder quality in perennial species such as sideoats gramma.

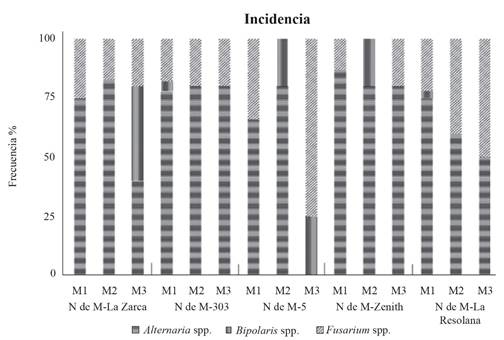

The Fusarium genus had 24% incidence and was found in the five varieties, with variable frequency among them; the fungus was isolated most frequently from M2 and M3, which indicates that the benefit to the caryopse improves the propagule’s health. The presence of Fusarium can be caused by its biological cycles, since, in areas with low environmental moisture, for example, the arid regions where sideoats gramma grows naturally, the infection is almost exclusively produced by the inoculum present in the soil, which invades and penetrates the stems and root base; for this reason, the chemical or biological protective agents added to the seed avoid seedling infestation, either from the accessory bracts or from the soil (Cook, 2010) and infect the whole plant. Finally, the Bipolaris genus, with 9% incidence, had the lowest number of isolates in the five varieties, of which NdeM-La Zarca in M3 had the greatest frequency (Figure 1). The Alternaria, Bipolaris and Fusarium genera are associated with leaf, stem and root diseases in grain crops, as well as the production of mycotoxins that negatively affect animal health (Sainz et al., 2012). Diseases like Damping-off and grain black point can be caused by Alternaria spp., Fusarium spp. and Bipolaris spp. (Rodríguez et al., 2009).

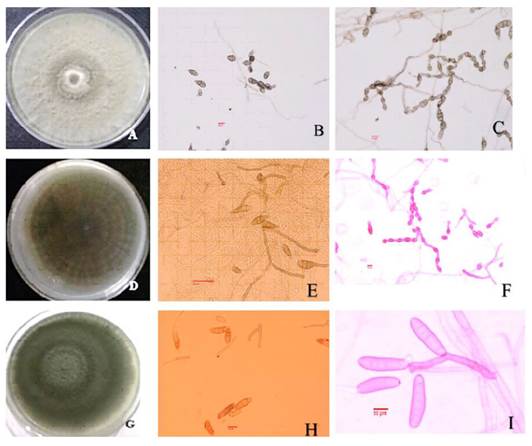

Morphological identification. Although no symptoms were observed on the seed, the presence of fungi that affect seedling development is important during sowing, since it will define the seedlings’ competitive capacity in a naturally challenging environment as well as their density in the prairie. Fifty-one (51) isolates of the three types of sample (M1, M2, M3) were obtained and five morphospecies were identified: Alternaria F and Alternaria-cl, Bipolaris-os, Fusarium 1 and Fusarium 2. Based on the taxonomic keys for each genus, the following species were identified: Alternaria-cl: colony gray in color in PCA culture medium, with rough-dotted ornamentation, obclavate, wall-like conidia, transversal septation of 1-6 and longitudinal septation with 0-3 septa, conidia size 15-34 x 6.3-13.5 µm, and primary conidiophores 12-46 x 3.8-5.4 µm in size. The catenulation can have 5-15 conidia, has secondary ramification, characteristics which, according to Simmons’ keys (1995), correspond to A. tenuissima (Figure 2A-2C). Alternaria F: colony gray-olive in color in PCA culture medium, obclavate, wall-like conidia with rough-dotted ornamentation, transversal septation of 1-6 and longitudinal septation of 0-3, conidia size 10.5-42 x 6.4-12.7 µm, and primary conidiophores 34.1- 44.8 x 3.1- 4.6 µm in size. The catenulation can have 5-10 conidia, abundant secondary ramification, which are characteristics that correspond to A. alternata (Simmons, 1995) (Figure 2D-2F). In this species, spores survive on the seed or in the mycelium inside the seed, and high humidity and temperatures of 20-25 °C favor their development. The A. alternata fungus has been isolated from wheat seeds (Bautista et al., 2011), and Leucaena (Lezcano et al., 2010); it causes leaf blight on oats (García et al., 2013), rot in fruit trees (Mariscal et al., 2017; Ruiz et al, 2017) and vegetables (Fraire et al., 2010). The effect of many fungi on perennial grasses can be pathogenic (Kononenko et al., 2015; Masi et al., 2017) and/or reinforce their resistance to diverse environmental pressures (Ali et al., 2017). Alternaria tenuissinna is present in wheat crops (Perello et al., 2015). These species produce mycotoxins that can be present in products such as flour, concentrates and processed foods, and can seriously affect human and animal health (Pavón et al., 2012).

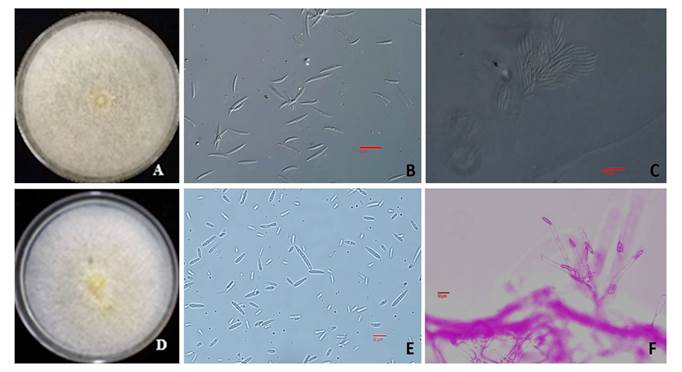

For the Fusarium 1 genus: the colony was beige in color with white mycelium that became brown as it grew older in PDA culture medium and spore masses were formed. The sporodochia observed were salmon-orange in color with thin macronidia showing a dorsiventral curve of 26-38.5 x 3-4.9 µm with 5-6 septa, needle-like apical cell, and foot-like basal cell. Ellipsoid microconidia measured 8.9-17.5 x 2.5-4.2 µm with 0-3 septa and short polyphialides, characteristics that correspond to F. scirpi (Leslie and Summerell, 2006) (Figure 3A-3C). This species is common in temperate, arid y semiarid regions (Summerell, 2019), grasslands and farmlands. It is considered a secondary pathogen but can cause legume root rot. Fusarium 2: the colony was pale orange-salmon in color in PDA culture medium, with abundant cottony mycelium, semi-straight and slightly curved macronidia of 27-36 x 3-4.5 µm with 3-5 septa, foot-like basal cell, sharp and curved apical cell, with abundant mesoconidia with 1-3 septa. These characteristics match those of F. incarnatun (Leslie and Summerell, 2006) (Figure 3D-3F). This fungus is present in the soil and in a wide range of tropical-desert environments considered of minor economic importance and is associated with pearl millet seed (Pennisetun americanum) (Wilson, 2002), soybean (Chiotta et al., 2015) and sorghum. Similarly, the presence of mycotoxins is often recognized in fodder with high moisture content and poor management: hay, silo and hay-silo. The presence of a great number of fungal metabolites (over 100, including mycotoxins, antibiotics and others whose action is not known) has been reported in cultivated fodder (Ramírez et al., 2014) and grassland species. However, many of their effects on grazing cattle are unknown (Nichea et al., 2015). Species belonging to the F. incarnatum-equiseti complex have been associated with diseases of grasses and mycotoxin production (Salvat et al., 2013).

Finally, the Bipolaris B-os genus: in PDA culture medium it produced colonies olive-brown in color with aerial mycelium, individual conidiophores with no ramification, that measured 43-160 x 4-6 µm, were septate and geniculated in the upper part, brown in color; and 21.5-49 x 10.5-15.8 µm conidia, smooth or slightly curved, cylindrical, brown in color with 2-6 septa, characteristics that correspond to B. cynodontis (Manamgoda et al., 2014) (Figure 2G-2I). This fungus was reported for the first time on Cynodon dactylon in 1909. It is considered a secondary saprophyte pathogen and can invade a wide range of hosts within the grasses (Poaceae). It is considered of low economic importance and has been reported as a pathogen in various grass species (González et al., 2006). For example, it induces foliar spots in Chloris gayana and C. dactylon (Hagan, 2005; Rodríguez, 2011).

Figure 1. Frequency of Alternaria, Bipolaris and Fusarium genera isolates of five commercial varieties of sideoats gramma (Bouteloua curtipendula) from spikelets, caryopses with lemmas and clean caryopses. M1: full spikelet; M2: caryopses with lemma; M3: clean caryopse.

Figure 2. Cultural and morphological characteristics of fungi associated with seed of sideoats gramma from Valle del Mezquital, Hidalgo. Fungi morphology. A-C) Alternaria tenuissima, A) Colony on PCA, B) Conidia, C) Conidia chain. D-F) Alternaria tenuissima, A) Colony on PCA, B) Conidia, F) Conidia chain. G-I) Bipolaris cyndontis, G) Colony on PDA, H) Conidia, I) Conidiophore.

Figure 3. Cultural and morphological characteristics of fungi associated with seed of sideoats gramma from Valle del Mezquital, Hidalgo. A-C) Fusarium scirpi, A) Colony on PDA, B) Macroconidia, C) Sporodochium. D-F) Fusarium incarnatum, D) Colony on PDA, E) Micro- and mesoconidia, F) Phialides.

Identification and molecular phylogeny. Based on the morphological identification, three DNA samples of the genera were sent to Macrogen® Inc., Korea. The DNA sequences obtained from the isolates were covered and identified by ≥99% as being different species of each genus of Alternaria, Bipolaris and Fusarium, which confirmed the previous identification of the genera based on morphological traits. Molecular phylogeny was used to determine the identity of each isolate (Figure 4). The sequences corresponding to the Alternaria genus were grouped in the clade that includes 10 species that form the A. alternata complex (Woudenberg et al., 2013). There is little molecular variation, and to determine the specific morphotypes, three or more genes must be sequenced (Woudenberg et al., 2015). However, based on their morphology (Simmons, 1995), it was corroborated that Alternaria F was A. alternata, and Alternaria-cl was A. tenuissima. Bipolaris-os sequencing was aligned with the clade that includes B. coffeana and B. cynodontis (Manamgoda et al., 2014), both of which are phylogenetically related. Based on the morphology and the description of Manamgoda et al. (2014), it corresponds to B. cynodontis. The Fusarium sequences were aligned with the incarnatum-equiseti complex that includes four species: F. incarnatum, F. equiseti, F. lacertarum and F. scirpi. The rDNA and EF1 ITS region did not show enough polymorphism to separate the four phylogenetically related species, which is in agreement with the results reported by O´Donnell et al. (2009). According to the morphology, F1 was identified as F. scirpi and F2 as F. incarnatum.

Conclusions

The evaluated seeds had low phytosanitary quality because of the incidence of Alternaria spp. (67%), Fusarium spp. (24%) and Bipolaris spp. (9%) in the five varieties and the three types of propagule. The species A. alternata, A. tenuissinna, F. incarnatum, F. scirpi and B. cynodontis were identified through morphological and molecular characterization and phylogeny as the main fungi associated with commercial seed of sideoats gramma (Bouteloua curtipendula) from Valle del Mezquital, Hidalgo. In Mexico, there are no previous studies about the presence of fungi in seed of native sideoats gramma, which is of great importance to recover grasslands. Based on this information, conducting further studies to determine the pathogenicity of the fungi isolated from seed is recommended, as well as epidemiological studies in the field in order to develop assertive strategies to promote higher sanitary quality of seed and improve the probability of establishing high-risk prairies under semiarid rainfed conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) for its support through the proposal of Problemas Nacionales 2014 (248252): “Colecta, salvaguarda y evaluación de forrajeras (Poaceae) para pastoreo extensivo, nativas de México semiárido”(Collection, safeguarding and evaluation of fodder crops (Poaceae) for extensive grazing, native to semiarid Mexico) and for the financial support it provided for conducting research through the Masters in Science scholarship granted to the second author of this study

REFERENCES

Afzal, I., R. Shabir and S. Rauf. 2019. Seed production technologies of some major field crops. In: Hasanuzzaman M. (ed.) Agronomic Crops. Springer, Singapore. pp. 655-678. [ Links ]

Ali, S., TC. Charles, BR. Glick. 2017. Endophytic phytohormones and their role in plant growth promotion. In: Doty, S (ed.) Functional Importance of the Plant Microbioma. Springer. Chap. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65897-1_6 [ Links ]

Arriagada, RV. 2012. Semillas. Inspección, análisis, tratamiento y legislación. Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura (IICA-O.E.A.) 115 p. http:// repiica.iica.int/docs/bv/agrin/b/f03/XL2000600205.pdf (consulta, diciembre 2018). [ Links ]

Barnett, HL. and Hunter, BB. 1972. Ilustred Genera of Imperfect Fungi. Burgess Publishing Company. Minnesota, USA. 241 p. [ Links ]

Bautista, EE., Leyva, MG., Villaseñor, ME., Huerta, EJ. y Mariscal, AA. 2011. Hongos asociados al grano de trigo sembrado en áreas del centro de México. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 29(2):175-177. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/rmfi/v29n2/v29n2a11.pdf [ Links ]

Chiotta, ML., Chulze, S. y Barros, G. 2015. Fuentes de inóculo de especies de Fusarium potenciales productoras de micotoxinas en el agroecosistema soja. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, 47(2):171-184. https://doi.org/10.19137/qs.v7i0.687 [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional del Agua (CONAGUA). 2018. Actualización de la disponibilidad media anual de agua en el acuífero Ixmiquilpan (1312), Estado de Hidalgo. Subdirección General Técnica. Gerencia de Aguas Subterráneas. Subgerencia de Evaluación y Ordenamiento de Acuíferos. Diario Oficial de la Federación. Enero 4, 2018. 34 p. [ Links ]

Cook,, RJ. 2010. Fusarium root, crown, and foot rots and associated seedling diseases. In: Compendium of wheat diseases and pests. In: W.W. Bockus, R. Bowden, R. Hunger, W. Morrill, T. Murray, and R. Smiley (eds.). 3rd. Ed. The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, USA. p. 37-39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496505. 2011.564100 [ Links ]

Crous, PW., Verkley, GJ., Groenewald, JZ., and Samson, RA. 2009. Fungal Biodiversity. CBS Laboratory Manual Series. Centraalbureau voor Schimmecultures, Utrecht, Netherlands. 269 p. [ Links ]

Fraire, CL., Nieto, AD., Cárdenas, SE., Gutiérrez, AG., Bujanos, MR. y Vaquera, HH. 2010. Alternaria tenuissima, A. alternata y Fusarium oxysporum hongos causantes de la pudrición del florete de brócoli. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 28(1):25-33. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-33092010000100003 [ Links ]

García, LE., Leyva, MG., Villaseñor, ME., Rodríguez, GF. y Tovar, PM. 2013. Identificación e incidencia de tres hongos fitopatógenos de reporte nuevo en avena (Avena sativa L.), en la meseta central de México. Agrociencia 47(8):815-827. https://doi.org/10.29312/ remexca.v0i8.1090 [ Links ]

Gilchrist, SL., Fuentes, GC., Martínez, CA., López, RE., Duveiller, PS., Henry, MI. y García, A. 2005. Guía práctica para la identificación de algunas enfermedades de trigo y cebada. Segunda Ed. 68 p. México. CIMMYT. (Consulta, mayo 2018). https://repository. cimmyt.org/ xmlui/handle/10883/1272 [ Links ]

González, AG., López, MM., Novo, A., Estrada, ZV., López, GM., Bernal, DA., Granda, BA., Rodríguez, AG., Figueredo, GG., Pupo, LZ., Ramos, AD., González, M., Ruiz, MG., Pérez, MG., Nápoles, IA., García, CR., Sánchez, GC., Buchillón, R. y López, CM. 2006. Fitopatógenos en los cultivos de pastos y forrajes en Cuba. Fitosanidad 10(1):11-18. http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2091/209116158002.pdf [ Links ]

Hagan, A. 2005. Leaf spot and rust diseases of turf grasses. Alabama Cooperative. Extension System. https://ssl.acesag.auburn.edu/pubs/docs/A/ ANR-0621/ANR-0621-archive.pdf (consulta, diciembre 2018). [ Links ]

Hall, TA. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Oxford University Press. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 41: 95-98. http://brownlab.mbio.ncsu.edu/JWB/papers/1999Hall1.pdf (consulta, junio de 2019) [ Links ]

Kidd, SE., Sharon, C., Chen, A., Meyer, W., Halliday, CL. 2019. A new age in molecular diagnostics for invasive fungal disease: are we ready? Frot. Microbiol. 10: 2903. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02903 [ Links ]

Kononenko, GP., Burkin, AA., Gavrilova, OP., Gagkaeva, TY. 2015. Fungal species and multiple mycotoxin contamination of cultivated grasses and legumes crops. Agricultural and Food Science. 24:323-330. https://doi.org/10.23986/afsci.52313 [ Links ]

Lamichhane, JR., You, MP., Laudinot, V., Barbette, MJ., and Aubertot, JN. 2020. Revisiting sustainability of fungicide seed treatments for field crops. Plant Disease 104:610-623. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-06-19-1157-FE [ Links ]

Leslie, JF. and Summerell, BA. 2006. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual. Blackwell Publishing. United States of America. 388 p. ISBN/ISNN: 978-0-8138-1919-8 [ Links ]

Lezcano, JC., Martínez, B. y Alonso, O. 2010. Caracterización cultural y morfológica e identificación de 12 aislamientos fungosos de semillas de Leucaena leucocephala cv. Perú. Pastos y Forrajes 33(1):1-14 pp. http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/pyf/v33n1/pyf04110.pdf [ Links ]

Lezcano, JC., Navarro, M., González, Y. y Alonso, O. 2007. Determinación de la calidad de las semillas de Leucaena leucocephala cv. Perú almacenadas al ambiente. Pastos y Forrajes 30(1):107-118. http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/pyf/v30n1/pyf06107.pdf [ Links ]

Manamgoda, DS., Rossman, A., Castlebury, LA., Crous, PW., Madrid, H., Chukeatirote, E., and Hyde, KD. 2014. The genus Bipolaris. Studies in Micology 79:221-228. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.10.002. [ Links ]

Mariscal, AL., Rivera, YA., Dávalos, GP. y Ávila, MD. 2017. Situación actual de hongos asociados a la secadera de la fresa (Fragaria x Ananassa Duch.) en Guanajuato, México. Agrociencia 51(6): 673-681. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/agro/v51n6/1405-3195-agro-51-06-00673-en.pdf [ Links ]

Masi, M., Meyer, S., Pescitelli, G., Cimmino, A., Clement, S., Peacock, B., and Evidente, A. 2017. Phytotoxic activity against Bromus tectorum for secondary metabolites of a seed-pathogenic Fusarium strain belonging to the F. trincinctum species complex. Natural Product Res. 31(23):2768-2777. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2017.1297445 [ Links ]

Morales, NC., Quero, CA., Melgoza, AC., Martínez, SM. y Jurado, GP. 2009. Diversidad forrajera del pasto Banderita [Bouteloua curtipendula (Michx.) Torr.], en poblaciones de zonas áridas y semiáridas de México. Técnica Pecuaria México 47(3):231-244. https://doi.org/10.22319/rmcp.v7i2.4174 [ Links ]

Nichea, MJ., Cendoya, E., Zachetti, VGL., Chiacchiera, SM., Sulyok, M., Krska, R., Torres, AM., Chulze, SN., and Ramírez, ML. 2015. Mycotoxin profile of Fusarium armeniacum isolated from natural grasses intended for cattle feed. World Mycotoxin Journal 8(4): 451-457. https://doi.org/10.3920/WMJ2014.1770 [ Links ]

O´Donnell, K., Sutton, DA., Rinaldi, MG., Gueidan, C., Crous, PW., and Geiser, DM. 2009. Novel multilocus sequence typing scheme reveals high genetic diversity of human pathogenic members of the Fusarium incarnatum-F. equiseti and F. chlamydosporum species complexes within the United States. J Clinical Microbiology 47(12):3851-3861. https//:doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01616-09 [ Links ]

Pavón, MM., González, AI., Martín, SR. y García, LT. 2012. Importancia del género Alternaria como productor de micotoxinas y agente causal de enfermedades humanas. Nutrición Hospitalaria 27(6):1772-1781. http://dx.doi.org/10.3305/nh.20 12. 27.6.6017 [ Links ]

Perello, AE., Aulicino, MB., Martinelli, C., Regueira, M., Moreno, MV. y Stenglein, S. 2015. Caracterización morfocultural de nuevos grupos taxonómicos de Alternaria, asociados a enfermedades del trigo en Argentina. Revista Ciencias Morfológicas 17(1):1-15. https://doi.org/10.35537/10915/53343 [ Links ]

Pirelli, GJ., Anderson, NP., Craig, AM., and Young, CA. 2016. Endophyte toxins in grass and other feed sources. Risk to Livestock. EM-9156. Oregon State University. 10 p. http://oregonstate.edu/endophyte-lab/files/ext-pub-nov-2016.pdf (Consulta, marzo, 2020). [ Links ]

Quero, CAR., Enríquez, QJF. y Miranda, JL. 2007. Evaluación de especies forrajeras en América tropical, avances o status quo. Interciencia 32(8):566-571. http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0378-18442007000800014 [ Links ]

Quero, CA., Miranda, J. L., Villanueva, Á. J. F. 2017. Recursos genéticos de gramíneas para el pastoreo extensivo. Condición actual y urgencia de su conservación ante el cambio climático. Avances en Investigación Agropecuaria. 3:63-85. [ Links ]

Quero-Carrillo, AR., Miranda-Jiménez, L., Hernández-Guzmán, F. y FA Rubio, A. 2014. Mejora del establecimiento de praderas de temporal. Folleto Técnico. Colegio de Postgraduados. ISBN: 978-607-715-213-2 31p. http//doi.org:10.13140/2.1.5101.2161 [ Links ]

Ramírez, ML., Chulze, SN., Torres, MA., Zachetti, GV., Nichea, JM., Cendova, E. y Palacios, AS. 2014. Variación estacional de la presencia de micotoxinas en pasturas naturales destinadas a la alimentación bovina. SNS (Argentina) 4:49-54. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, G. 2011. Patógenos fungosos que afectan a gramíneas procedentes de la Estación Experimental de Pastos y Forrajes “Las Tunas”. Unidad Experimental “Indio Hatuey”, Universidad de Matanzas “Camilo Cienfuegos” Cuba. https://biblioteca.ihatuey.cu/link/tesis/tesism/gisellerodriguez.pdf (consulta, septiembre 2018). [ Links ]

Rodríguez, CG, Iglesias C, Nieto TM y Palmero, D. 2009. La enfermedad de la punta negra del trigo. Agricultura. Revista Agropecuaria 195:118-121. ISSN 0002-1334. (consultada, mayo 2019). http://oa.upm.es/15517/ [ Links ]

Ruiz CF, Ríos VC, Berlanga RD, Ornelas PJ, Acosta MC, Romo CA, Zamudio FP, Pérez CD, Salas MM, Ibarra RJ y Fernández PS. 2017. Incidencia y agentes causales de enfermedades de raíz y sus antagonistas en manzanos de Chihuahua, México. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 35(3):437-462. https://dx.doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.1704-3 [ Links ]

Sainz MJ, Aguin O, Bande MJ, Pintos C y Mansilla JP. 2012. Biodiversidad de especies de Fusarium en tallos de maíz forrajero en Galicia. Pastos 42(1):51-56. [ Links ]

Saitou N and Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 4(4):406-425. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454 [ Links ]

Salvat A, Balbuena O, Ricca A, Comerio R, Rosello BJ, Rojas D, Berretta M, Delssin E, Bedascarrasbure E y Salerno J. 2013. Presencia de zearalenona en pasturas del Este del Chaco. Revista de Investigaciones Agropecuarias 39(1):31-36. [ Links ]

Sambrook J and Russel DW. 2001. Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory Manual. Third edition. New York. Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press 1:1. 32-1. 34 p. [ Links ]

Simmons, EG. 1995. Alternaria themes and variations (112-144). Mycotaxon. 55:55-163. [ Links ]

Summerell, BA. 2019. Resolving Fusarium: Current status of the genus. Ann Rev. of Phytopatology. 57:323-339. https://doi.org/10.1146/annualvev-phyto-082718-100204. [ Links ]

Tamura K, Nei M, and Kumar S. 2004. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101: 11030-11035. https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0404206101 [ Links ]

Warham E.J., Butler L. y Sutton B. 1998. Ensayos para la Semilla de Maíz y de Trigo. Manual de Laboratorio. Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo. México. 64 p. [ Links ]

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, and Taylor J. 1990. Amplification and Direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis, MA., Gelfand, DA., Sninsky, JJ., White, TJ. (eds.) PCR Protocols. A Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press, CA, USA p. 315-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-372180-8.5002-1 [ Links ]

Wilson, JP. 2002. Fungi associated with the stalk rot complex of pearl millet. Plant Disease 86:833-839. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS.2002.86.8.833 [ Links ]

Woudenberg, JH., Groenewald, JZ., Binder, M., and Crous, PW. 2013. Alternaria redefined. Studies in Mycology 75(1):171-212. https://doi.org/10.3114/sim0015 [ Links ]

Woudenberg, JH., Seidl, MF., Groenewald, JZ., Vries, M., Stielow, JB., Thomma, BP., and Crous, PW. 2015. Alternaria section Alternaria: Species, formae speciales or pathotypes? Studies in Mycology 82:1-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simyco.2015.07.001 [ Links ]

Received: February 06, 2020; Accepted: April 18, 2020

texto em

texto em