Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de fitopatología

On-line version ISSN 2007-8080Print version ISSN 0185-3309

Rev. mex. fitopatol vol.38 n.1 Texcoco Jan. 2020 Epub Nov 27, 2020

https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.1909-2

Scientific articles

Morphological and genetic characterization of Corynespora cassiicola isolates obtained from roselle and associated weeds

1Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias y Ambientales, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero, Periférico Poniente s/n. CP 40020. Iguala de la Independencia, Guerrero, México;

2 Posgrado en Fitosanidad-Fitopatología, Colegio de Postgraduados, Carretera México-Texcoco Km 36.5, Montecillo, CP 56230, Texcoco, Estado de México, México;

Several Corynespora cassiicola isolates obtained from roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) and nine associated weeds to this crop were morphological and phylogenetically analyzed. The fungal isolates were divided into two groups: group one included 37 isolates obtained from H. sabdariffa and eight obtained from other host plants including Solanum lycopersicum, Chromolaena odorata, Senna alata, Eugenia oerstediana, Passiflora viridiflora, Momordica charantia, Ricinus communis and Gossypium hirsutum; in this case, the predominant colonies were gray, dense texture and polygonal in shape. Group two included two isolates obtained from H. sabdariffa and one from Hyptis suaveolens; in this group the colonies were mainly cream and pale brown, dense and round. Comparative analysis with isolates of C. cassiicola from other countries showed that group one isolates were mainly associated with those isolated from the Solanaceae family, while those from group two were related to those of the Cucurbitaceae family. To our knowledge, this is the first study on the morphological and genetic characterization of C. cassiicola in Mexico.

Key words: Hibiscus sabdariffa; leaf spot; phylogenetic analysis

Se analizaron morfológica y filogenéticamente diferentes aislados de Corynespora cassiicola obtenidos de jamaica (Hibiscus sabdariffa) y nueve malezas asociadas al cultivo. Los aislados fúngicos se dividieron en dos grupos: el grupo uno incluyó 37 aislados obtenidos de H. sabdariffa y ocho obtenidos de otros hospedantes como Solanum lycopersicum, Chromolaena odorata, Senna alata, Eugenia oerstediana, Passiflora viridiflora, Momordica charantia, Ricinus communis y Gossypium hirsutum; en este caso, las colonias predominantes fueron de color gris, textura densa y forma poligonal. El grupo dos, incluyó a dos aislados obtenidos de H. sabdariffa y uno de Hyptis suaveolens; en este grupo, las colonias fueron principalmente de color crema y café pálido, densas y redondeadas. El análisis comparativo con aislados de C. cassiicola de otros países mostró que los aislados del grupo uno referidos anteriormente se asociaron principalmente con aquellos aislados de la familia Solanaceae, mientras que los del grupo dos se relacionaron con los de la familia Cucurbitaceae. Para nuestro conocimiento este es el primer estudio sobre la caracterización morfológica y genética de C. cassiicola en México.

Palabras clave: Hibiscus sabdariffa; mancha foliar; análisis filogenético

Corynespora cassiicola is a plant pathogenic fungus that causes foliar spots in economically important crops such as squash (Cucurbita pepo), cucumber (Cucumis sativus), soybean (Glycine max), rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis), papaya (Carica papaya) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), among others (Silva et al., 2003; Dixon et al., 2009; Qi et al. 2011; Paz et al., 2018). In addition to leaves, the pathogen infects other plant organs, including stems, roots, flowers and fruits (Deon et al., 2014); it is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical regions of many countries (Dixon et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009).

In Mexico, roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) is a crop of great economic value with an annual area sown of 20,061 ha, mainly in the state of Guerrero, where over than 70% of dehydrated calyxes are produced (SIAP, 2016). In this state, roselle leaf and calix spots caused by C. cassiicola have become the most important crop disease in the last years (Ortega et al., 2015; Hernández et al., 2018).

The genetic characterization of C. cassiicola has been evaluated using different techniques, including RAPD, ISSR, AFLP, iPBS and phylogeny (Silva et al., 2003; Dixon et al., 2009; Qi et al., 2011; Deon et al., 2014; Oktavia et al., 2017; Silva et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019). In the case of phylogeny, partial regions of the β-tubulin gene, 1-α elongation factor (EF-1α), calmodulin and actin have been amplified, as well as internal transcribed spacers (Shimomoto et al., 2011; Oktavia et al., 2017). The analysis of variability of the fungus has been used in ecological and epidemiological studies and for developing management strategies (Qi et al., 2011; Oktavia et al., 2017; Sumabat et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2018). Since there are no studies about the characterization of this fungus in Mexico, the objective of this study was to characterize morphological and genetically several C. cassiicola isolates obtained from roselle leaves and calyxes, as well as weeds associated with the crop in the state of Guerrero.

Materials And Methods

Fungi isolation. From 2013 to 2015, roselle leaves and calyxes, as well as leaves of weeds associated with the crop showing necrotic lesions, were collected in different sites of the state of Guerrero. Foliar tissue sections were taken from the area in which the lesion was growing, disinfested with 1% sodium hypochlorite and cultured on Petri dishes containing a potato-dextrose-agar (PDA) medium. The obtained colonies were purified using the monosporic culture technique.

Morphology and growth rate of colonies. Using 5-day-old monosporic cultures, fragments of 0.5 cm in diameter were taken from the edge of the colonies (Qi et al., 2011), placed at the center of new Petri dishes with PDA and incubated at 28 °C (three replications per isolate) (Onesirosan et al., 1974). The diameter of the colonies was measured every 24 h for five days considering the average length of two right-angle diameters (Qi et al., 2011). Based on these data, the growth rate was calculated using the following formula: Growth rate = (Df-Di)/(Tf-Ti), where: Df = Final diameter of growth; Di= Initial diameter of growth; Tf=Final time; Ti= Initial time.

Morphology of conidia. Digital images of conidia obtained from each 5-day-old monosporic isolate were taken using an AmScope® MU 1000 camera attached to an Eclipse Ci optical microscope (Nikon®, Japan). The length and width of 50 conidia were measured, and their forms registered. Measurements were taken using a micrometric ruler with which the ImageTool® v3.0 image analyzer was calibrated. (Hernández et al., 2005). Data on conidia growth rate, size and morphology were tabulated and subjected to an analysis of variance and mean separation (Duncan, α=0.01) using SAS 9.4 version software.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing. For this purpose, the protocol described by Sambrook and Rusell (2001) was followed, using mycelium from 12-day-old monosporic colonies that were kept at 28 °C on Petri dishes with PDA. A segment of the EF-1α gene was amplified with EF1-728F/EF1-986R primers (Carbone and Kohn, 1999). The PCR reaction mixture was prepared with 2 µL of IX PCR buffer, 0.6 µL of MgCl2 2.0 μM, 0.2 µL of dNTP´s 0.2 mM, 0.6 µL of each primer (10 µM), 0.1 µL of Taq DNA polymerase 0.5 U (Promega®, USA) and 10 ng of DNA extracted from the fungus. The final mixture was adjusted by adding sterile ultra-pure water at a 10 μL final volume and amplified in a thermocycler (Techne-TC-512®, USA), according to the program described by Shimomoto et al. (2011). The obtained amplicons were purified with Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega®, USA) and sequenced in both directions in Macrogen Inc®.

Phylogenetic analysis. The sequences obtained from each isolate were edited and aligned using the SeqMan Pro module of the DNASTAR LaserGene® program to generate a consensus sequence. The phylogenetic tree was built following the Neighbour-joining (NJ) method (Saitou and Nei, 1987), using the genetic distances that were calculated according to the two-parameter model (Kimura, 1980) with the MEGA version 7.0 program. To re-construct the phylogenetic tree, the partial sequence of the EF-1α gene of Corynespora smithii available in the GenBank (Access number AB539437) was used as an organism external to the group. The sequences obtained from C. cassiicola isolates in this study were deposited in the GenBank with access numbers MF000841-MF000888, and compared to other sequences available for this species (AB539285, AB539271, AB539291, AB539301, AB539235, AB539260, KY082897, KY290565, KP735616, KP834309, KP834310, AB539270, AB539283 and AB539269).

Results

A total of 48 C. cassiicola isolates were obtained, 39 of roselle plants and 9 of weeds associated with the crop distributed in 4 municipalities and 15 sites across the state of Guerrero (Table 1).

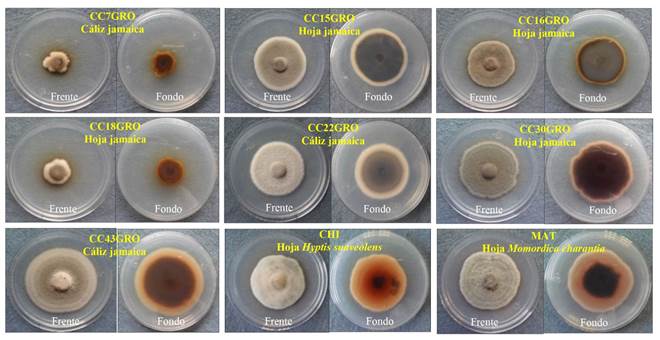

Morphology and growth rate of the colonies. The colonies grown in PDA had uniform growth, developed an abundant aerial mycelium, and their morphology showed variation among isolates (Figure 1). The front side of the colonies was white, gray or green in color, while the center was white, brown, light brown, gray or dark gray. The texture in the front side varied from thin to thick, and the growth form from round to polygonal (Table 2). The average grown rates and size of the colonies showed significant differences among isolates (Table 3). The CC33GRO isolate had the highest growth rate with 0.67 centimeter/day (cm/d), and the greatest average diameter (5.07 cm) compared to those of CC07GRO and CC36GRO isolates, which had the lowest growth rate and lowest average diameter of colony (Table 3).

Table 1. Corynespora cassiicola isolates obtained from roselle plants and weeds associated with the crop in the state of Guerrero, Mexico.

| Municipio | Aislado | Hospedante | Familia | Tejido |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tecoanapa | CC1GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC3GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC4GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC5GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC6GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Tecoanapa | CC7GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Tecoanapa | CC9GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Tecoanapa | CC10GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC11GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC12GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC13GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC14GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC15GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC16GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC17GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC18GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC19GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | CC21GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CC22GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Ayutla | CC26GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | CC27GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | CC29GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Ayutla | CC30GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | CC32GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Ayutla | CC33GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | CC34GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | CC36GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | CC38GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | CC40GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| San Marcos | CC42GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Xochistlahuaca | CC43GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Tecoanapa | CC44GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Tecoanapa | CC45GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Tecoanapa | CC46GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Tecoanapa | CC47GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Tecoanapa | CC48GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Tecoanapa | CC49GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Ayutla | CC50GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Cáliz |

| Ayutla | CC51GRO | H. sabdariffa | Malvaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | JIT | Solanum lycopersicum | Solanaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | M26 | Chromolaena odorata | Asteraceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | GUG | Senna alata | Fabaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | CHI | Hyptis suaveolens. | Lamiaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | CAP | Eugenia oerstediana | Myrtaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | PAS | Passiflora viridiflora | Passifloraceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | MAT | Momordica charantia | Cucurbitaceae | Hoja |

| Tecoanapa | HGA | Ricinus communis | Euphorbeaceae | Hoja |

| Ayutla | ALG | Gossypium hirsutum | Malvaceae | Hoja |

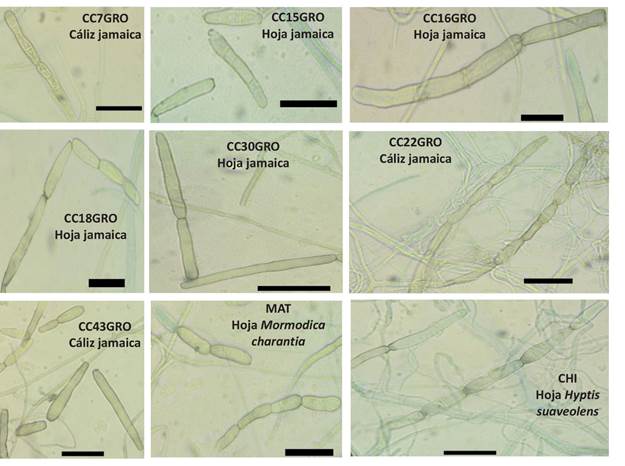

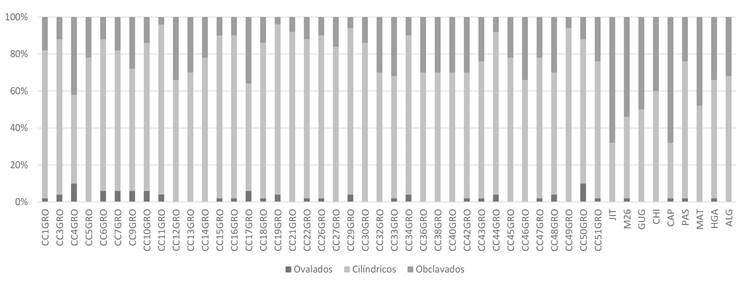

Morphology of conidia. A significant level of morphological difference was observed in conidia of the different isolates that were analyzed. The observed forms of conidia were oval, obclavate and cylindrical with straight or curve contours (Table 3, Figures 2, 4 and 5). The maximum and minimum average size ranged from 8.4-305.4 µm x 2.9-23.0 µm (length x width, respectively); the number of pseudosepta was 0 to 15. Significant statistical differences among isolates (Table 3) were found. Conidia with cylindrical form prevailed (73%) followed by obclavate (24.75%) and oval conidia (2.25%) (Figure 5). The CC9GRO isolate had the greatest mean conidial size (111.68 µm), while the CC17 (8.38 µm) had the highest average width. The smallest average length was observed in CC21GRO and CC50GRO isolates (28.31 µm and 28.39 µm, respectively) and the JIT isolate had the conidia with the lowest average width (5.12 µm). The CAP isolate had the greatest average number of pseudosepta (5 pseudosepta), and PAS had the lowest average number of pseudosepta (0.62) (Table 3).

Phylogenetic analysis. The 48 C. cassiicola isolates used in this study were divided into two groups: group 1 formed by 37 isolates obtained from roselle, and 8 isolates from weeds associated with the crop; group 2 formed by 2 isolates obtained from roselle and 1 from weed associated with the crop (Figure 3).

Discussion

Among the different C. cassiicola isolates that were analyzed, a significant level of differences was observed in colony color, texture, form and size, as well as in the form, size, contour and number of conidia pseudosepta (Tables 2 and 3, Figures 2, 4 and 5), which coincides with reports published by other authors (Onesirosan et al., 1974; Nghia et al., 2008; Qi et al., 2011). Genetic differences were also observed considering the analysis of a segment of the EF-1a gene, which was reported in Japan by Shimomoto et al. (2011) in C. cassiicola isolates obtained from Cucumis sativus, Solanum lycopersicun, Capsicum annuum, among other plant species. The comparative analysis of the isolate sequences obtained in the present study, along with other that were available in the GenBank, showed that the isolates from group 1 were associated with those obtained from species of the Apocynaceae (14%), Ericaceae (29%) and Solanaceae (57%) families from Japan, USA and India, while the isolates of group 2 were associated with those obtained from species of the Ericaceae (14%), Lamiaceae (14%), Asteraceae (29%) and Cucurbitaceae (43%) families from China, Japan, USA and the Netherlands. These results indicate that the Mexican C. cassiicola isolates belonging to group 1 are more related to those obtained from plants of the Solanaceae family, while the isolates of group 2 are more associated with species of the Cucurbitaceae family. On the other hand, within group 1, there was a tendency to form a subgroup of isolates collected from weeds associated with the roselle crop in Mexico (Hernández et al., 2018): JIT (Solanum lycopersicum (in wild form), M26 (Chromolaena odorata), PAS (Pasiflora viridiflora), MAT (Momordica charantia) and CAP (Eugenia oerstediana). The isolates of group 1 were collected in the municipalities of Ayutla, Tecoanapa, Xochistlahuaca and San Marcos, and those of group 2 were collected in the municipality of Ayutla (Figure 3; Table1). In this regard, it was observed that this group had a certain relationship with the place of origin, a fact that was reported by other authors (Silva et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2009). Dixon et al. (2009) analyzed diverse C. cassiicola isolates from 68 plant species collected in American Samoa, Brazil, Malaysia, Micronesia and USA, and determined that those geographically different but obtained from the same plant species were very similar at the genetic level, which suggested a certain level of specialization with the host (Sumabat et al., 2018). The specificity of C. cassiicola isolates with their host has also been suggested in the case of papaya, tomato and cucumber (Silva et al., 2018).

Figure 1 Morphological diversity of Corynespora cassiicola isolates obtained from roselle plants (Hibiscus sabdariffa) and weeds associated with the crop.

Tabla 2. Color, texture, form, growth rate and size of colonies of Corynespora cassiicola isolated from roselle and weeds associated with the crop five days after incubation.

| Aislado | Color | Textura | Forma | Tasa de crecimiento (cm/d)¶ | Tamaño (cm)¶ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parte Superior | Fondo | Promedio±SE | Promedio±SE | |||

| CC1GRO | Gris | Negro | Densa | Polígono | 0.40hijk±0.03 | 3.45hijkl±0.15 |

| CC3GRO | Café pálido | Gris claro | Densa | Redonda | 0.45cdefghij±006 | 3.93defghi±0.37 |

| CC4GRO | Gris | Café pálido | Ligera | Polígono | 0.34jklm±0.01 | 3.38hijkl±0.03 |

| CC5GRO | Café pálido | Blanca | Densa | Redonda | 0.58abcdef±0.03 | 4.68abcd±0.11 |

| CC6GRO | Gris | Gris oscuro | Ligera | Polígono | 0.43fghijk±0.03 | 3.60fghijk±0.13 |

| CC7GRO | Café claro | Café oscuro | Ligera | Polígono | 0.10o±0.02 | 1.88op±0.09 |

| CC9GRO | Gris | Café pálido | Densa | Polígono | 0.31jklm±0.02 | 2.90klm±0.06 |

| CC10GRO | Verde | Gris | Densa | Polígono | 0.31jklm±0.03 | 3.18ijkl±0.11 |

| CC11GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Polígono | 0.34jklm±0.01 | 3.10jklm±0.05 |

| CC12GRO | Crema | Gris | Densa | Redonda | 0.52abcdefgh±0.06 | 3.92efghi±0.26 |

| CC13GRO | Naranja ligero | Café pálido | Densa | Polígono | 0.22lmno±0.00 | 2.57mno±0.03 |

| CC14GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Polígono | 0.29klmn±0.06 | 2.83lmn±0.19 |

| CC15GRO | Gris | Oscuro | Ligera | Redonda | 0.62ab±0.02 | 4.28bcdefg±0.07 |

| CC16GRO | Crema | Gris | Ligera | Polígono | 0.44defghijk±0.02 | 3.70efghij±0.10 |

| CC17GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Polígono | 0.29klmn±0.01 | 2.55mno±0.03 |

| CC18GRO | Gris | Café pálido | Ligera | Polígono | 0.19mno±0.01 | 2.15nop±0.05 |

| CC19GRO | Gris claro | Gris | Ligera | Redonda | 0.44defghijk±0.01 | 3.67efghij±0.04 |

| CC21GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Redonda | 0.59abcde±0.02 | 4.43abcde±0.02 |

| CC22GRO | Crema | Gris | Densa | Redonda | 0.55abcdefgh±0.01 | 4.43abcde±0.01 |

| CC26GRO | Gris | Oscuro | Densa | Polígono | 0.23lmno±0.01 | 2.53mno±0.07 |

| CC27GRO | Gris | Café oscuro | Densa | Polígono | 0.22lmno±0.03 | 2.48mno±0.20 |

| CC29GRO | Verde | Negro | Densa | Polígono | 0.42fghijk±0.01 | 3.97defgh±0.02 |

| CC30GRO | Verde | Café oscuro | Densa | Polígono | 0.53abcdefgh ±0.02 | 4.33abcdef±009 |

| CC32GRO | Gris claro | Gris | Densa | Redonda | 0.57abcdefg±0.04 | 4.43abcde±0.15 |

| CC33GRO | Gris | Negro | Densa | Redonda | 0.67a±0.02 | 5.07a±0.04 |

| CC34GRO | Gris | Gris oscuro | Densa | Redonda | 0.54abcdefgh±0.03 | 4.25bcdefg±0.15 |

| CC36GRO | Gris | Café oscuro | Densa | Polígono | 0.13o±0.01 | 1.73p±0.06 |

| CC38GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Polígono | 0.36ijkl±0.03 | 3.17jklm±0.09 |

| CC40GRO | Naranja ligero | Café pálido | Densa | Polígono | 0.40hijk±0.05 | 3.57ghijkl±0.22 |

| CC42GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Redonda | 0.59abcd±0.02 | 4.35abcdef±0.12 |

| CC43GRO | Crema | Naranja ligero | Densa | Redonda | 0.62ab±0.05 | 4.97ab±0.24 |

| CC44GRO | Crema | Café oscuro | Ligera | Polígono | 0.24lmn ±0.01 | 2.88klm±0.03 |

| CC45GRO | Café pálido | Café claro | Ligera | Polígono | 0.15no±0.00 | 1.87op±0.02 |

| CC46GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Redonda | 0.53abcdefgh±0.04 | 3.95defgh±0.28 |

| CC47GRO | Crema | Gris Claro | Densa | Polígono | 0.50bcdefghi±0.05 | 3.98defgh±0.22 |

| CC48GRO | Crema | Gris | Densa | Redondo | 0.42ghijk±0.05 | 3.78efghij±0.26 |

| CC49GRO | Gris | Crema | Densa | Redonda | 0.45cdefghij±0.07 | 3.85efghij±0.33 |

| CC50GRO | Crema | Crema | Densa | Redonda | 0.45defghijk±0.02 | 3.93defghi±0.10 |

| CC51GRO | Gris | Negro | Densa | Redonda | 0.46cdefghij±0.05 | 3.83efghij±0.22 |

| JIT | Gris | Crema | Ligera | Polígono | 0.42ghijk±0.02 | 3.57ghijkl±0.07 |

| M26 | Gris | Café pálido | Ligera | Polígono | 0.41ghijk±0.02 | 3.37hijkl±0.11 |

| GUG | Gris | Café pálido | Densa | Redonda | 0.65ab±0.01 | 4.83abc±0.17 |

| CHI | Gris | Café pálido | Densa | Redonda | 0.61abc±0.10 | 4.75abc±0.51 |

| CAP | Gris claro | Gris | Ligera | Redonda | 0.53abcdefgh±0.05 | 4.10cdefgh±0.20 |

| PAS | Verde | Café pálido | Densa | Redonda | 0.53abcdefgh±0.00 | 4.35abcdef±0.03 |

| MAT | Gris | Café pálido | Densa | Polígono | 0.55abcdefgh±0.05 | 4.25bcdefg±0.28 |

| HGA | Naranja ligero | Café pálido | Densa | Polígono | 0.32jklm±0.02 | 3.10jklm±0.10 |

| ALG | Gris | Café claro | Densa | Polígono | 0.43efghijk±0.03 | 3.82efghij±0.11 |

¶ Data are the average of three replications. Means with the same letter in the same column are not significantly different (P=0.01) based on Duncan’s multiple range test.

Table 3. Conidia size and number of pseudosepta of Corynespora cassiicola isolates from roselle and weeds associated with the crop (average of 50 conidia/isolate).

| Aislado | Color | Textura | Forma | Tasa de crecimiento (cm/d)¶ | Tamaño (cm)¶ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parte Superior | Fondo | Promedio±SE | Promedio±SE | |||

| CC1GRO | Gris | Negro | Densa | Polígono | 0.40hijk±0.03 | 3.45hijkl±0.15 |

| CC3GRO | Café pálido | Gris claro | Densa | Redonda | 0.45cdefghij±006 | 3.93defghi±0.37 |

| CC4GRO | Gris | Café pálido | Ligera | Polígono | 0.34jklm±0.01 | 3.38hijkl±0.03 |

| CC5GRO | Café pálido | Blanca | Densa | Redonda | 0.58abcdef±0.03 | 4.68abcd±0.11 |

| CC6GRO | Gris | Gris oscuro | Ligera | Polígono | 0.43fghijk±0.03 | 3.60fghijk±0.13 |

| CC7GRO | Café claro | Café oscuro | Ligera | Polígono | 0.10o±0.02 | 1.88op±0.09 |

| CC9GRO | Gris | Café pálido | Densa | Polígono | 0.31jklm±0.02 | 2.90klm±0.06 |

| CC10GRO | Verde | Gris | Densa | Polígono | 0.31jklm±0.03 | 3.18ijkl±0.11 |

| CC11GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Polígono | 0.34jklm±0.01 | 3.10jklm±0.05 |

| CC12GRO | Crema | Gris | Densa | Redonda | 0.52abcdefgh±0.06 | 3.92efghi±0.26 |

| CC13GRO | Naranja ligero | Café pálido | Densa | Polígono | 0.22lmno±0.00 | 2.57mno±0.03 |

| CC14GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Polígono | 0.29klmn±0.06 | 2.83lmn±0.19 |

| CC15GRO | Gris | Oscuro | Ligera | Redonda | 0.62ab±0.02 | 4.28bcdefg±0.07 |

| CC16GRO | Crema | Gris | Ligera | Polígono | 0.44defghijk±0.02 | 3.70efghij±0.10 |

| CC17GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Polígono | 0.29klmn±0.01 | 2.55mno±0.03 |

| CC18GRO | Gris | Café pálido | Ligera | Polígono | 0.19mno±0.01 | 2.15nop±0.05 |

| CC19GRO | Gris claro | Gris | Ligera | Redonda | 0.44defghijk±0.01 | 3.67efghij±0.04 |

| CC21GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Redonda | 0.59abcde±0.02 | 4.43abcde±0.02 |

| CC22GRO | Crema | Gris | Densa | Redonda | 0.55abcdefgh±0.01 | 4.43abcde±0.01 |

| CC26GRO | Gris | Oscuro | Densa | Polígono | 0.23lmno±0.01 | 2.53mno±0.07 |

| CC27GRO | Gris | Café oscuro | Densa | Polígono | 0.22lmno±0.03 | 2.48mno±0.20 |

| CC29GRO | Verde | Negro | Densa | Polígono | 0.42fghijk±0.01 | 3.97defgh±0.02 |

| CC30GRO | Verde | Café oscuro | Densa | Polígono | 0.53abcdefgh ±0.02 | 4.33abcdef±009 |

| CC32GRO | Gris claro | Gris | Densa | Redonda | 0.57abcdefg±0.04 | 4.43abcde±0.15 |

| CC33GRO | Gris | Negro | Densa | Redonda | 0.67a±0.02 | 5.07a±0.04 |

| CC34GRO | Gris | Gris oscuro | Densa | Redonda | 0.54abcdefgh±0.03 | 4.25bcdefg±0.15 |

| CC36GRO | Gris | Café oscuro | Densa | Polígono | 0.13o±0.01 | 1.73p±0.06 |

| CC38GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Polígono | 0.36ijkl±0.03 | 3.17jklm±0.09 |

| CC40GRO | Naranja ligero | Café pálido | Densa | Polígono | 0.40hijk±0.05 | 3.57ghijkl±0.22 |

| CC42GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Redonda | 0.59abcd±0.02 | 4.35abcdef±0.12 |

| CC43GRO | Crema | Naranja ligero | Densa | Redonda | 0.62ab±0.05 | 4.97ab±0.24 |

| CC44GRO | Crema | Café oscuro | Ligera | Polígono | 0.24lmn ±0.01 | 2.88klm±0.03 |

| CC45GRO | Café pálido | Café claro | Ligera | Polígono | 0.15no±0.00 | 1.87op±0.02 |

| CC46GRO | Gris | Gris | Ligera | Redonda | 0.53abcdefgh±0.04 | 3.95defgh±0.28 |

| CC47GRO | Crema | Gris Claro | Densa | Polígono | 0.50bcdefghi±0.05 | 3.98defgh±0.22 |

| CC48GRO | Crema | Gris | Densa | Redondo | 0.42ghijk±0.05 | 3.78efghij±0.26 |

| CC49GRO | Gris | Crema | Densa | Redonda | 0.45cdefghij±0.07 | 3.85efghij±0.33 |

| CC50GRO | Crema | Crema | Densa | Redonda | 0.45defghijk±0.02 | 3.93defghi±0.10 |

| CC51GRO | Gris | Negro | Densa | Redonda | 0.46cdefghij±0.05 | 3.83efghij±0.22 |

| JIT | Gris | Crema | Ligera | Polígono | 0.42ghijk±0.02 | 3.57ghijkl±0.07 |

| M26 | Gris | Café pálido | Ligera | Polígono | 0.41ghijk±0.02 | 3.37hijkl±0.11 |

| GUG | Gris | Café pálido | Densa | Redonda | 0.65ab±0.01 | 4.83abc±0.17 |

| CHI | Gris | Café pálido | Densa | Redonda | 0.61abc±0.10 | 4.75abc±0.51 |

| CAP | Gris claro | Gris | Ligera | Redonda | 0.53abcdefgh±0.05 | 4.10cdefgh±0.20 |

| PAS | Verde | Café pálido | Densa | Redonda | 0.53abcdefgh±0.00 | 4.35abcdef±0.03 |

| MAT | Gris | Café pálido | Densa | Polígono | 0.55abcdefgh±0.05 | 4.25bcdefg±0.28 |

| HGA | Naranja ligero | Café pálido | Densa | Polígono | 0.32jklm±0.02 | 3.10jklm±0.10 |

| ALG | Gris | Café claro | Densa | Polígono | 0.43efghijk±0.03 | 3.82efghij±0.11 |

¶ Means with the same letter in the same column are not significantly different (P=0.01) based on Duncan’s multiple range test.

Figure 2 Morphological diversity of conidia of C. cassiicola isolates obtained from roselle and weeds associated with the crop. Bars=30 µm.

Figure 4 Distribution in percentage of contours of conidia of C. cassiicola isolates obtained from roselle and weeds associated with the crop.

Figure 5 Distribution in percentage of the form of conidia of C. cassiicola isolates obtained from roselle and weeds associated with the crop.

Figure 3. Phylogenetic tree of Corynespora cassiicola isolates obtained from roselle and weeds associated with the crop based on partial sequences of the EF-1a gene. Corynespora smithii was used as an organism external to the group.

However, so far, it has not been possible to definitely establish an association of C. cassiicola phylogenetic groups with their geographical origin or hosts (Deon et al., 2014). In addition to the latter, subsequent studies could be focused on exploring the pathogenic variability of C. cassiicola in the formed groups considering the amplification of other regions, such as β-tubulin, calmodulin and actin, or the analysis of iPBS markers in order to determine if there is a relationship between the level of pathogenicity with the groups and subgroups formed in the present study and their host.

Conclusions

The results of the morphological and phylogenetic analyses showed significant differences among the C. cassiicola isolates collected from roselle plants and weeds associated with the crop, which are related to isolates from other countries that were obtained mainly from plant species of the Solanaceae and Cucurbitaceae families.

Literatura Citada

Carbone, I. and Kohn, LM. 1999. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 91: 553-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.1999.12061051 [ Links ]

Deon, M., Fumanal, B., Gimenez, S., Bieysse, D., Oliveira, RR. and Shuib, SS. 2014. Diversity of the cassiicolin gene in Corynespora cassiicola and relation with the pathogenicity in Hevea brasiliensis. Fungal Biology 118: 32-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2013.10.011 [ Links ]

Dixon, LJ., Schlub, RL., Pernezny, K. and Datnoff, LE. 2009. Host specialization and phylogenetic diversity of Corynespora cassiicola. Phytopathology 99:1015-1027. https://doi.org/10.1094/phyto-99-9-1015 [ Links ]

Hernández, MJ., Ochoa, MDL., Ortega, ASÁ. and Vega, MR. 2018. Survey on alternative hosts of Corynespora cassiicola, the cause of the leaf and calyx spot, in the surroundings of roselle fields in Mexico. Tropical Plant Pathology 43: 263-270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40858-017-0206-9 [ Links ]

Hernández, LRA., Llanderal, CC., Castillo, MLE., Valdez, CJ. and Nieto, HR. 2005. Identification of larval instars of Comadia redtenbacheri (Hamm) (Lepidoptera: cossidae). Agrociencia 39:539-544. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=30239507 [ Links ]

Kimura, M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. Journal of Molecular Evolution 16: 11l-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01731581 [ Links ]

Nghia, NA., Kadir, J., Sunderasan, E., Abdullah, PM., Malik, A. and Napis, S. 2008. Morphological and inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers analyses of Corynespora cassiicola isolates from rubber plantations in Malaysia. Mycopathologia 166:189-201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-008-9138-8 [ Links ]

Oktavia, F., Kuswanhadi, Widodo, Dinarti, D. and Sudarsono. 2017. Pathogenicity and RDNA-ITS sequence analysis of the Corynespora cassiicola isolates from rubber plantations in Indonesia. Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture 29(11): 872-83. https://doi.org/10.9755/ejfa.2017.v29.i11.1497 [ Links ]

Onesirosan, PT., Arny, DC. and Durbin, RD. 1974. Hostspecificity of Nigerian and North American isolates of Corynespora cassiicola. Phytopathology 64:1364-1367. https://doi.org/10.1094/phyto-64-1364 [ Links ]

Ortega, ASÁ., Hernández, MJ., Ochoa, MDL. and Ayala, EV. 2015. First report of Corynespora cassiicola causing leaf and calyx spot on roselle in Mexico. Plant Disease 99:1041. https://doi.org/10.1094/pdis-04-14-0438-pdn [ Links ]

Paz, DS., Gusmão, JAR., Costa, AA., Silva, EKC. and Diniz, NB. 2018. Reaction of papaya genotypes to target spot and activity of plant extracts and Bacillus spp. on Corynespora cassiicola. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura. 40(1): (e-098). https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-29452018927 [ Links ]

Qi, Y-X., Zhang, X., J-J, P., Liu, X-M., Lu, Y., Zhang, H., Hui-Qiang, Z., YanChao, L. and Yi-Xian, X. 2011. Morphological and molecular analysis of genetic variability within isolates of Corynespora cassiicola from different hosts. European Journal of Plant Pathology 130:83-95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-010-9734-6 [ Links ]

Saitou, N. and Nei, M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 4(4):406-425. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454 [ Links ]

Sambrook, J. and Russel, D. 2001. Rapid isolation of yeast DNA. In: Molecular cloning, a laboratory manual 3th Ed. (Green MR and Sambrook J, eds.). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, New York, pp. 3.17-3.32. [ Links ]

Shimomoto, Y., Sato, T., Hojo, H., Morita, Y., Takeuchi, S., Mizumoto, H., Kiba, A. and Hikichi, Y. 2011. Pathogenic and genetic variation among isolates of Corynespora cassiicola in Japan. Plant Pathology 60:253-260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02374.x [ Links ]

SIAP. 2016. Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. (Consulta, febrero 2019). [ Links ]

Silva, WPK., Karunanayake, EH., Wijesundera, RLC. and Priyanka, UMS. 2003. Genetic variation in Corynespora cassiicola: A possible relationship between host origin and virulence. Mycologial Research 107:567-571. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0953756203007755 [ Links ]

Silva, B. JL., Galúcio, S. FM., Gomes, L. MT., Ferreira, V. MS., Almeida, FV. and Reboucas, D. LC. 2018. Genetic variability if Corynespora cassiicola isolates from Amazonas, Brazil. Arquivos do Instituto Biológico 85:1-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1808-1657000992017 [ Links ]

Smith, LJ., Datnoff, LE., Pernezny, K. and Schlub, RL. 2009. Phylogenetic and pathogenic characterization of Corynespora cassiicola isolates. Acta Horticulturae 808: 51-56. https://doi.org/10.17660/actahortic.2009.808.6 [ Links ]

Sumabat, L., Robert, CK.., and Brewer, TM. 2018. Phylogenetic diversity and host specialization of Corynespora cassiicola responsible for emerging target spot disease of cotton and other crops in the southeastern United States. Phytopathology 108: 892-901. https://doi.org/10.1094/phyto-12-17-0407-r [ Links ]

Wu, J., Xie, X., Shi, Y., Chai, A., Wang, Q. and Li, B. 2019. Analysis of pathogenic and genetic variability of Corynespora cassiicola based on iPBS retrotransposons. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 41(1):76-86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07060661.2018.1516239. [ Links ]

Received: September 27, 2019; Accepted: December 04, 2019

text in

text in