Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de fitopatología

versão On-line ISSN 2007-8080versão impressa ISSN 0185-3309

Rev. mex. fitopatol vol.37 no.2 Texcoco Mai. 2019 Epub 30-Set-2020

https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.1810-4

Scientific Articles

Efficacy of indigenous and commercial Simplicillium and Lecanicillium strains for controlling Hemileia vastatrix

1 Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Campo Experimental Delicias. Carretera Delicias-Rosales Km 2.5. Delicias, Chihuahua, México, CP. 33000 México;

2 Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International, Turrialba, Cartago, Costa Rica, CP. 30501 Costa Rica.

The aim of this research was to select an indigenous strain of Simplicillium with a high degree of virulence, as well as to assess the efficacy of commercial strains of mycoparasites for the control of H. vastatrix in Costa Rica. The study included eight strains of fungi, five of them were isolated from the coffee region of Turrialba, which were identified as Simplicillium lanosoniveum and three biopesticides recommended to control coffee rust in Costa Rica. The EC strain showed to be the most effective, by colonizing coffee rust pustules in a shorter time. This strain was compared with commercial formulations after two successive passes in PDA and after been stored on filter paper. The indigenous isolates showed a greater degree of specificity than the rest of the strains. This is the first report pointing out Simplicillium as the main natural enemy of H. vastatrix in Costa Rica.

Key words: indigenous isolates; colonization rate; mycoparasites

La roya es la enfermedad del café de mayor importancia económica, puede ocasionar pérdidas de producción superiores a 50%. La información sobre prácticas de control biológico aplicado para controlar la roya del café en Costa Rica es limitada. El estudio tuvo por objetivo seleccionar una cepa local de Simplicillium con alto grado de virulencia, así como evaluar la eficiencia de cepas comerciales de micoparásitos destinados al control de H. vastatrix en Costa Rica. El estudio comprendió ocho cepas de hongos, cinco de ellas fueron aisladas de la zona cafetalera de Turrialba e identificadas como Simplicillium lanosoniveum y tres biofungicidas comerciales recomendados para combatir la roya en cafetales de Costa Rica. La cepa EC mostró ser la más efectiva al colonizar en menor tiempo las pústulas de roya. Esta cepa fue comparada con formulados comerciales después de dos pases sucesivos en PDA y de haberla almacenado en papel filtro. Los aislamientos locales presentaron un mayor grado de especificidad que el resto de las cepas. Estos son los primeros resultados que anteponen a Simplicillium como principal agente de control biológico de H. vastatrix en Costa Rica.

Palabras clave: aislamientos locales; porcentaje de colonización; micoparásitos

Within the complex of diseases that attack coffee crops, rust (Hemileia vastatrix Berk. and Broome) is one of the most important, since it can cause losses in production higher than 50% (Haddad et al., 2009; Suresh et al., 2012). The most harmful outbreak of rust in Central America occurred in the 2012-2013 cycle, when losses were estimated in over US$499 million, leading several countries to consider the event as a national emergency (Promecafe e IICA, 2013).

When a mycoparasite is regulating a phytopathogen in a natural way, it must be isolated and evaluated as a control agent (Campbell, 1990). Such is the case of the fungus, with a cotton-like appearance, that frequently parasites the coffee rust and that is cited as Lecanicillium lecanii Zimm. (Monzón, 1992; Canjura et al., 2002; Vandermeer et al., 2009; Rivillas, 2015; Pérez, 2015). It has recently been proven that, in coffee plantations in the region of Turrialba, Cartago, Costa Rica, the main natural enemy of H. vastatrix is the fungus Simplicillium Gams and Zare (García, 2018), a taxon related with Lecanicillium (Zare and Gams, 2001). So once the correct identification is carried out, it is necessary to carry out an evaluation in vitro to select strains of greater virulence up to H. vastatrix.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the biological control of H. vastatrix can be a feasible and environmentally safe technique for the control of the disease; Monzón (1992), when evaluating Verticillium Nees for the control of rust in the laboratory, showed that the germination of uredospores is reduced. Vélez and Rosillo (1995), using a strain of V. lecanii (= Lecanicillium), also recorded a delay in the incubation period of H. vastatrix and in the reduction of the total incidence of the disease per plant. Likewise, Haddad et al., (2009) documented the use of bacteria as a promising technique for the biological control of H. vastatrix.

Currently, the control of rust in Costa Rica is focused on the use of protector (copper-based) and systemic fungicides that belong to the family of triazols, mainly (the undesireable effects of these control actions are well-known), along with cultural practices such as pruning, the use of shade and the use of resistant varieties (Avelino et al., 2004; Barquero, 2013). Although the use of resistant varieties is a promising practice for the mitigation of the disease, the genetic variety of rust reduces the time of initial resistance (Gouveia et al., 2005). On the other hand, there are natural enemies of H. vastatrix that regulate its incidence and severity (Guharay et al., 2001), such as the fungi L. lecanii and Cladosporium hemileiae (=Digitopodium hemileiae Steyaert). It is also common to find larvae of Mycodiplosis Rüb. feeding of rust pustules (Virginio Filho, 2017). Unfortunately, the information on applied biological control practices for the control of coffee rust in Costa Rica is limited.

The aim of the study was to isolate and compare local and commercial strains of Simplicillium and Lecanicillium against coffee rust.

Materials and methods

Isolation and identification of local and commercial strains. The study covered eight fungal strains, five of which were isolated from rust pustules in the coffee-growing region of Turrialba, Cartago, Costa Rica, in the locations of San Juan Norte (SJ), Jabillos (JV), Aquiares (AQ), Santa Rosa (SR) and CATIE (EC). A variation of this last strain was also included after having been kept for one month using the filter paper method (Morales, 2008) in order to observe the loss of virulence due to dehydration at the end of the process (codified as EC1). The plots in which the collections were performed are located between 600 and 950 masl; the average temperature recorded in the area of study in recent years has been 22.4°C and a relative humidity of 90.6%. All plots were planted with Arabica coffee of the variety Caturra, with a density of 5000 plants/ha under shade.

The three remaining strains (INA, C1 and C2) are products recommended against rust in coffee plantations in Costa Rica. INA comes from a training and technology transfer center; this strain reproduces in a traditional manner, using rice as a substrate. C1 was also produced with the same substrate, but unlike the above, it was packaged and labeled for sale. C2 is a commercial product which was formulated as a wettable powder.

Monospori colonies of the different strains were sent to the Molecular Biology Lab of the Corporación Bananera Nacional de Costa Rica (National Banana Corporation of Costa Rica - Corbana). For the sequencing of the samples, the genetic material was extracted following the protocol described by Kuske et al. (1998) with modifications made by Corbana, followed by an amplification of the ITS region. The primers used for the amplification were ITS1 and ITS4; the corroboration of the amplification was carried out in a 1% agarose gel. The product of the amplification was sent to the company Macrogen Inc. for purifying and sequencing. After generating the sequences, they were edited using the program BioEdit and compared in the database of the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information). The organisms identified for each product are shown in Table 1. The strains are safeguarded in the Microbial Control Laboratory of the Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (Tropical Agriculture Research and Training Center - CATIE).

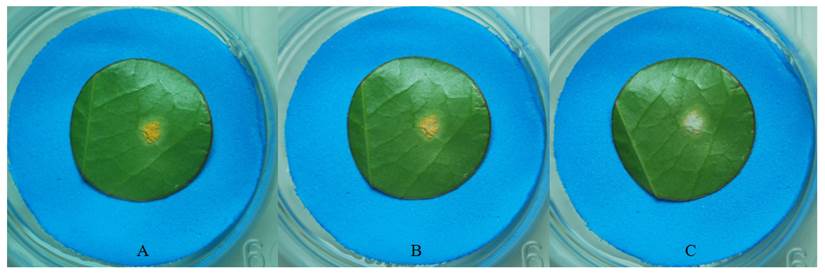

Collection of rust pustules and preparation of leaf discs. Initially, leaves of the coffee variety Caturra, fully developed and with rust pustules in different stages of development without microparasitic fungi were collected; these leaves were transferred to a lab, where, using a hole puncher, 1.8 cm in diameter, we extracted leaf discs with rust pustules with deep orange-colored, recently sporulated (intermediate stage) lesions and fully developed lesions colored pale orange (advanced stage). Once the leaf discs were made, they were placed in a CELLSTAR(R) multiwell plate with six cavities, each of which previously contained 5 mL of sterile distilled water (SDW), and on top of this, a Foam disc, 2.5 cm in diameter. Finally, the leaf discs were placed on top of the Foam discs floating on SDW (Figure 1). They were then inoculated with a suspension of spores from the different strains, as described in the next section.

Table 1 Organisms identified in local and commercial strains.

| Cepa | Organismos coincidentes NCBI |

|---|---|

| EC | Simplicillium lanosoniveum |

| AQ | Simplicillium lanosoniveum |

| SR | Simplicillium lanosoniveum |

| SJ | Simplicillium lanosoniveum |

| JV | Simplicillium lanosoniveum |

| INA | Simplicillium lanosoniveum |

| C1 | Lecanicillium attenuatum |

| C2y | Lecanicillium sp. |

yIdentificación hecha en base a las claves taxonómicas pro puestas por Zare y Gams (2001) / y Identification performed based on the taxonomic codes proposed by Zare and Gams (2001).

Application method and doses. Petri dishes with 15 day old monospore cultures of the different strains were flooded with SDW, followed by scraping with a Drigalsky spatula until the mycelium was completely separated from the culture medium. The supernatant obtained was recovered in glass, which were placed in an ultrasonic bath for three minutes, then stirred in a vortex for one minute. They were then filtered to separate conidia from mycelia. Next, serial dilutions were carried out in SDW plus TweenR 80 to 0.1% until concentrations were obtained that allowed a spore count using a hemocytometer. After determining the number of conidia contained in the initial suspension, it was adjusted to a final concentration of 1x107 conidia/mL.

Figure 1 Leaf discs with rust pustules in an advanced stage and inoculated with the strain CATIE: A) two days after inocu lation; B) three days after inoculation, and C) four days after inoculation.

Strain C2 was packaged as a wettable powder, while INA and C1 were produced in rice, therefore, for the estimation of the concentration of spores, we first took one gram of the product that was suspended in 10 mL in SDW, followed by a filtration in a hemocytometer, and finally, it was adjusted to the same dose of the local strains based on the percentage of viability of each product.

The inoculation of the conidia on the leaf discs with rust was carried out using a DeVilbiss Modelo 15-RD sprayer. A volume of 0.27 mL of the final concentration was applied.

After spraying, it was left to stand until the humidity obtained during inoculation was lost, and then placed in the multiwell plate, as described in the previous section.

Measurement of the response variable. The variable measured was the percentage of colonization of the strains on the pustules of H. vastatrix. Measurements were made every 24 hours until 7 days after inoculation. To estimate the daily percentage of colonization, it was necessary to take daily, individual photographs of each leaf disc (Figure 1) to then process with the change of colors using the program ImageJ 1.47v (Rasband, 2016). Initially, we selected and measured the area covered by the rust lesion. Next, we adjusted the color threshold in such a way that the milky-white color due to the colonization of Simplicillium on the pustules was clearly defined. Finally, the percentage of colonization was calculated by dividing the area covered by Simplicillium by the total area of the lesion and multiplied the result by 100.

Design and statistical analysis. The experiment had 10 replicates, each one consisted of two multiwell plate, which contanied six discs with one stage of development of rust (intermediate or advanced); five of these discs were inoculated, each one with a different strain, in such a way that a sixth disc was used as a control without inoculation. The analysis was carried out using General Linear and Mixed Models using the Infostat statistical package (Di Rienzo et al., 2016). Growth curves were adjusted using mixed, non-linear models; the model that best described the growth curves was chosen using criteria AIC and BIC. Finally, an ANOVA was carried out, along with means separation test (LSD=0.05) for the coefficients Beta (increase in percentage of colonization).

Results

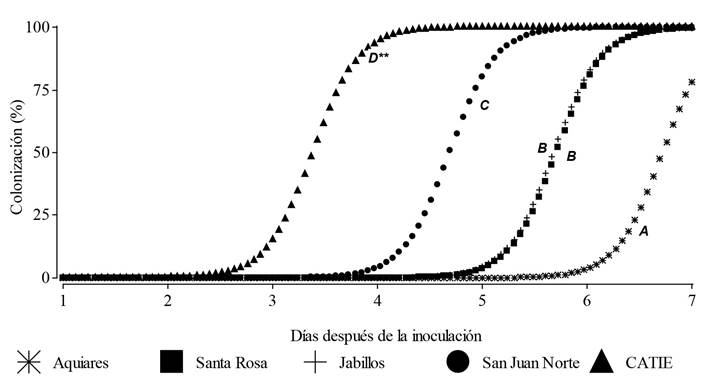

Bioassay of local strains against H. vastatrix. The statistical analysis shows a highly significant difference between the evaluated strains (F4,81=44.58, p˂ 0.0001). The progress in percentage of colonization of strains had a similar behavior in both stages evaluated; in other words, there was no statistical difference for the stage of rust development (F1,81=2.73, p=0.1025). Strain EC proved to be the most effective, since it colonized the rust pustules in the least amount of time, followed by SJ; the third most effective strains were SR and JV, with values that had no statistical difference (LSD=0.05). Strain AQ proved to have a lower performance rate in comparison to the rest (Figure 2).

Bioassay of commercial strains against H. vastatrix. After comparing the commercial strains and the best local strain selected in the previous trial, a highly significant statistical difference (F4,81=76.55, p˂0.0001) was observed. As in the previous experiment, the evaluated variable did not differ statistically in the stages of development of rust pustules (F1,81=5.06, p=0.0272). The highest percentages of colonization in the lowest times were recorded in strain EC, which, after having been stored with the filter paper method, did not undergo a loss in virulence. In second place in terms of efficacy was INA, and finally, with a very poor performance, were commercial strains C2 and C1 (Figure 3).

Discussion

These are the first results that report the effect of Simplicillium as the main biological control agent for H. vastatrix in Costa Rica. Most publications referring to the biological control of rust in coffee crops focus on the use of Lecanicillium as a biological control agent (Esques et al., 1991; Monzón, 1992; Rivas et al., 1996; Canjura et al., 2002; Vandermeer et al., 2009; Jackson et al., 2012; Rivillas, 2015; Pérez, 2015). This is partly to the fact that some related studies were made before the division of the genus Verticillium by Zare and Gams (2001), and in other cases, there is no taxonomic or molecular identification of the isolated strain, and the assumption is made that it is Lecanicillium , due to the morphological characteristics they share (Lim et al., 2014). Studies performed in the same region in which the strain CATIE was isolated mention that Lecanicillium can naturally parasite rust pustules in levels near 9% in coffee plantations under the shade (Pico 2014). On the other hand, Canjura et al. (2002) evaluated different strains of Verticillium isolated in the same region applied on greenhouse plants, and did not find differences in the incidence of rust pustules; these authors recorded a natural parasitism of 10.5%. Monzón (1992) found that applying Verticillium can reduce the germination of uredospores by 60%. Other studies have shown that the presence of Verticillium psalliotae on coffee leaves reduces the severity of the damage caused by rust. Likewise, the germination of uredospores was affected significantly when they were put in contact with conidia of the mycoparasite (Mahfud et al., 2006).

**Means with the same letter do not differ statistically (LSD=0.05).

(AQ: Aquiares; SR: Santa Rosa; JV: Jabillos; SJ: San Juan Norte; EC: CATIE)

Figure 2 Efficacy of local strains of Simplicillium spp. colonizing H. Vastatrix pustules

**Means with the same letter do not differ statistically (LSD=0.05).

(C2: commercial; C1: commercial; INA: traditional; EC1: stored CATIE; EC: CATIE)

Figure 3 Efficiency of commercial strains in the colonization of H. Vastatrix pustules

The results obtained in this study indicate a higher degree of specificity of the local isolations, from S. Lanosoniveum, in comparison with the commercial strains evaluated. A relevant observation is that the strain INA, obtained from the Instituto Nacional de Aprendizaje (National Training Institute) of Costa Rica, according to the analyses for its identification, belong to the genus Simplicillium, as well as local strains; this strain was the second most efficient after EC and EC1, which only strengthens what was mentioned earlier. This is inferred by strains C1 (L. attenuatum) and C2 (Lecanicillium sp.) being unable to colonize completely, and weren’t even able to cover 50%. Our results coincide with similar studies carried out in Mexico by Gómez et al., (2017), who isolated and evaluated the control effect of different strains of mycoparasitic fungi in rust pustules, and determined that the fungus Simplicillium offers 88.86% of parasitism 120 h after inoculation, whereas Lecanicillium reached 68.1% in the same period of time.

It is important to point out that the commercial strains C1 and C2 presented low values of purity and viability (data not shown), and although the application rate was adjusted according to this, a loss of virulence due to the process of production and formulation is possible, making it crucial to constantly evaluate the quality of biofungicides for the management of H. vastatrix in Costa Rica. Along with the tests of purity, concentration and viability, biopesticide formulators must undergo routine tests of effectiveness towards the goal organism, particularly at the end of the formulation process.

Based on the above, it is convenient that, before strains of mycoparasites are introduced for the management of H. vastatrix, locally present strains are explored, or in this case, products based on Simplicillium be used, and not to assume, as has been the case so far, that Lecanicillium is the main natural regulator of H. vastatrix in Costa Rica, since this assumption can be determinant in the failure of programs of biological control against rust.

Along with this, it is advisable to evaluate fungicides that may have a certain degree of selectivity towards Simplicillium in order to favor the biological control by conservation, or in this case, to opt for strains that are resistant to fungicides commonly used for controlling H. vastartrix in Costa Rica.

In addition to the main objective of the study, it has been proven that the method of conservation using filter paper does not diminish the pathogenicity of Simplicillium towards H. Vastatrix; the use of this method has proven to be efficient in the conservation of entomopathogenic and phytopathogenic fungi for more than five years without affecting its pathogenic capacity (Morales, 2008); although the EC strain had only been stored for one month at the moment of evaluating it, it is worth highlighting its capacity to tolerate the final desiccation at the end of the process without being affected, as well as its rapid recovery from the filter paper to be used.

Conclusions

The results obtained show that the local S. lanosoniveum strains are more efficient than commercial Lecanicillium - based products for colonizing rust pustules. Simplicillium shows a high degree of specificity towards H. vastatrix, and therefore, for the area of study, it is recommended that companies that manufacture biofungicides or the treatment of this disease focus on local strains of Simplicillium before formulating products with other genera.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the CONACYT and INIFAP for the support provided.

REFERENCES

Avelino J, Willocquet L and Savari S. 2004. Effects of crop management patterns on coffee rust epidemics. Plant Pathology 53(5): 541-547. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1365-3059.2004.01067.x [ Links ]

Barquero MM. 2013. Recomendaciones para el combate de la roya del cafeto (Hemileia vastatrix Berk et Br.). Tercera edición. Instituto del Café en Costa Rica. 63 p. [ Links ]

Campbell R. 1989. Biological control of microbial plant pathogens. Cambridge University Press. New York, USA, 218 p. [ Links ]

Canjura SEM, Sánchez GV, Krauss U y Somarriba E. 2002. Reproducción masiva de Verticillium sp. hiperparásito de la roya del café, Hemileia vastatrix. Manejo Integrado de Plagas y Agroecología 66:1319. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324212242_Reproduccion_masiva_de_Verticillium_sp_hiperparasita_de_la_roya_del_cafe_Hemileia_vastatrix [ Links ]

Di Rienzo JA, Casanoves F, Balzarini MG, González L, Tablada M y Robledo CW; InfoStat versión 2016. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. http://www.infostat. com.ar [ Links ]

Esques A, Mendes MDL and Robbs CF. 1991. Laboratory and field studies on parasitism of Hemileia vastatrix with Verticillium lecanii and V. leptobactrum. Café Cacao Thé. 35(4): 275-282. [ Links ]

García NG. 2018. Evaluación de la calidad y métodos de producción de bioplaguicidas para el manejo de Hemileia vastatrix en plantaciones de café. Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza. Tesis de doctorado. Turrialba, Costa Rica. 62 p. http://repositorio.bibliotecaorton.catie.ac.cr/bitstream/handle/11554/8823/Evaluaci on_de_la_calidad.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

Gómez DCI, Pérez PE, Escamilla PE, Martínez BM, Carrion VGLL y Hernández LTI. 2017. Selección in vitro de micoparásitos con potencial de control biológico sobre roya del café (Hemileia vastatrix). Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 36(1):172-183. http://www.rmf.smf.org.mx/ojs/index.php/RMF/article/view/93/90 [ Links ]

Gouveia MMC, Ribeiro A, Várzea VMP and Rodríguez CJ. 2005. Genetic diversity in Hemileia vastatrix base on RAPD markers. Mycologia 97(2):396-404. http://www.academia.edu/5506510/Genetic_diversity_in_Hemileia_vastatrix_based_on_RAPD_markers [ Links ]

Guharay F, Monterroso D and Staver C. 2001. El diseño y manejo de la sombra para la supresión de plagas en cafetales de América Central. Agroforestería en las Américas 8(29):22-29. Disponible en línea: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285079004_El_diseno_y_ manejo_de_la_sombra_para_la_supresion_de_plagas_en_cafetales_de_America_Central [ Links ]

Haddad F, Maffia LA, Mizubuti ESG and Teixeira H. 2009. Biological control of coffee rust by antagonistic bacteria under field conditions in Brazil. Biological Control 49(2):114-119. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1049964409000474 [ Links ]

Jackson D, Zemenick K and Huerta G. 2012. Ocurrence in the soil and dispersal of Lecanicillium lecanii a fungal pathogen of the green coffee scale (Coccus viridis) and coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix). Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 15(2):389-401. http://www.revista.ccba.uady.mx/ojs/index.php/TSA/article/view/912/741 [ Links ]

Kuske CR, Banton KL, Adorada DL, Stark PC, Gil KK and Jackson JP. 1998. Smal - scale DNA sample preparation method for filed PCR detection of microbial cells and spores in soil. Applied and Enviromental Microbiology 64(7): 2463-2472. [ Links ]

Lim SY, Lee S; Kong HG and Lee J. 2014. Entomopathogenicity of Simplicillium lanosoniveum isolated in Korea. Mycobiology 42(4):317-321. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4298834/ [ Links ]

Mahfud MC, Mior AZA, Meon S and Kadir J. 2006. In vitro and in vivo tests for parasitism of Verticillium psalliotae Treschow on Hemileia vastatrix BERK. And BR. Malaisian Journal of Microbiology. 2(1):46-50. http://mjm.usm.my/uploads/issues/117/research8.pdf [ Links ]

Monzón JA. 1992. Distribución de Verticillium sp. en tres zonas cafetaleras de Nicaragua y evaluación de dos aislamientos del hongo como agente de control biológico de la roya (Hemileia vastatrix) del cafeto (Coffea arabica L.). Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza. Tesis de maestría. Turrialba, Costa Rica. 66 p. [ Links ]

Morales A. 2008. A simple way to preserve fungal cultures. Cornell University. https://blog.mycology.cornell.edu/2008/01/10/a-simple-way-to-preserve-fungal-cultures/ [ Links ]

Pérez, V. L. 2015. La roya del cafeto (Hemileia vastatrix) en Cuba: Evolución al manejo alternativo de la enfermedad. In Memorias del Seminario Científico Internacional “Manejo Agroecológico de la Roya del Café”. FAO. Panamá, Panamá p. 17-19. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5137s.pdf [ Links ]

Pico RJT. 2014. Efecto de la sombra del café y el manejo sobre la incidencia, severidad, cantidad de inóculo y dispersión de Hemileia vastatrix en Turrialba, Costa Rica. Thesis Mag. Sc. Turrialba, Costa Rica, CATIE. 65 p. http://repositorio.bibliotecaorton.catie.ac.cr/bitstream/handle/11554/7054/Efecto_de_la_sombra_del_cafe.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

Promecafé (Programa Cooperativo Regional para el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Modernización de la Caficultura); IICA (Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura. 2013. La crisis del café en Mesoamérica. Causas y respuestas apropiadas. http://promecafe.net/documents/Publicaciones/la%20roya%20en%20centroamerica.pdf [ Links ]

Rasband WS. 2016. ImageJ. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda. Maryland, USA. Disponible en línea: https://imagej.net/ImageJ [ Links ]

Rivas, S; Leguizamón. J; Ponce, C. 1996. Estudio histológico, anatómico y morfológico de Verticillium lecanii y Talaromyces wortmannii con Hemileia vastatrix. Cenicafe 47(1):16-31. [ Links ]

Rivillas OCA. 2015. Acciones emprendidas por Colombia en el manejo de la roya del cafeto. en Memorias del Seminario Científico Internacional “Manejo Agroecológico de la Roya del Café”. Panamá, Panamá. FAO. p. 11-16. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5137s.pdf [ Links ]

Suresh N, Ram AS and Shivanna MB. 2012. Coffee leaf rust and disease triangle: A Case Study. International Journal of Food, Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences 2(2):50-55. [ Links ]

Vandermeer J, Perfecto I and Liere H. 2009. Evidence for hyperparasitism of coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix) by entomogenous fungus, Lecanicillium lecanii, through a complex ecological web. Plant Pathology 58(4):636-641. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.2009.02067.x [ Links ]

Vélez APE y Rosillo GAG. 1995. Evaluación del antagonismo del hongo Verticillium lecanii, sobre Hemileia vastatrix, en condiciones de invernadero y de campo. Cenicafé 46(1): 45-55. http://biblioteca.cenicafe.org/handle/10778/693 [ Links ]

Virginio Filho EM. 2017. Cafetales sanos, productivos y ambientalmente amigables. Guía para trabajo con familias productoras. Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza. Turrialba, Costa Rica. 32 p. http://www.iica.int/sites/default/files/publications/files/2018/BVE18029722e.pdf [ Links ]

Zare R and Gams W. 2001. A revision of Verticillium section Prostrata. IV. The genera Lecanicillium and Simplicillium gen. nov. Nova Hedwigia 73:1-50. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rasoul_Zare/publication/279556292_A_revision_of_Verticillium_section_Prostrata_IV_The_genera_Lecanicillium_and_Simplicillium_gen_nov/links/5694de6408ae425c6897b3fd/A-revision-of-Verticillium-section-Prostrata-IV-The-genera-Lecanicillium-and-Simplicillium-gen-nov.pdf [ Links ]

Received: October 24, 2018; Accepted: March 11, 2019

texto em

texto em