Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de fitopatología

On-line version ISSN 2007-8080Print version ISSN 0185-3309

Rev. mex. fitopatol vol.37 n.1 Texcoco Jan. 2019 Epub Aug 21, 2020

https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.1808-1

Scientific articles

Description and comparison among morphotypes of Fusarium brachygibbosum, F. falciforme and F. oxysporum pathogenic to watermelon in Sonora, México

1 Laboratorio de Biología Molecular, Departamento de Agricultura y Ganadería, Universidad de Sonora, Carretera Hermosillo-Bahía Kino Km 21, Hermosillo, Sonora, CP. 83000, México.

2 Universidad Estatal de Sonora, Avenida Ley Federal del Trabajo S/N, Colonia Apolo, Hermosillo, Sonora, CP. 83000, México;

3 Departamento de Investigaciones Científicas y tecnológicas, Universidad de Sonora, Luis Donaldo Colosio S/N, Colonia Centro, Hermosillo, Sonora, CP. 83000, México.

Abstract Fusarium brachygibbosum, F. falciforme and F. oxysporum have been recently identified as the cause of wilt and death in watermelon plants in Sonora, Mexico. Because of the scarce morphological information about F. brachygibbosum and in order to establish the distinctive macroscopic and microscopic characteristics among the species, the present study described four morphotypes of F. brachygibbosum and their comparison with three of F. falciforme and two of F. oxysporum. The categorization of morphotypes was based on the form of growth, mycelial tonalities and color developed in potato dextrose agar from 32 pathogenic Fusarium isolates in watermelon. The four morphotypes of F. brachygibbosum presented thick walled single and double chlamydospores, intercalary and terminal. Short monophialides and scarce polyphialides; macroconidia with apical slightly hook shaped cells and basal cells with a typical or slight foot shape. The greater thickness of the walls was distinctive in chlamydospores of F. brachygibbosum. The morphology of the macroconidia was different in the three species. A distinctive characteristic of F. falciforme morphotypes was the long and thin monophialides while in those of F. oxysporum was the absence of septa in the microconidia. The size of macroconidia and microconidia was significantly different among the morphotypes but not within the species.

Key words: wilting; macroconidia; microconidia; chlamydospores; polyphialides.

Recientemente se ha identificado a Fusarium brachygibbosum, F. falciforme y F. oxysporum como causantes de marchitez y muerte en plantas de sandía en Sonora, México. Debido a la escasa información morfológica acerca de F. brachygibbosum y con el fin de establecer las características macroscópicas y microscópicas distintivas entre las especies, en el presente trabajo se realizó la descripción de cuatro morfotipos F. brachygibbosum y su comparación con tres de F. falciforme y dos de F. oxysporum. La categorización de los morfotipos se realizó, con base en la forma de crecimiento, tonalidades del micelio y el color desarrollado en agar-dextrosa-papa, a partir de 32 aislados de Fusarium patogénicos en sandía. Los cuatro morfotipos de F. brachygibbosum presentaron clamidosporas sencillas o dobles, de pared gruesa, intercalares y terminales. Monofiálides cortas y escasas polifiálides. Macroconidios con células apicales en ligera forma de gancho y células basales con forma típica o ligera forma de pie. El mayor grosor de paredes fue distintivo en las clamidosporas de F. brachygibbosum. La morfología de los macroconidios fue diferente en las tres especies. Una característica distintiva en los morfotipos de F. falciforme fueron las monofiálides largas y delgadas; mientras que en los de F. oxysporum fue la ausencia de septos en los microconidios. El tamaño de los macroconidios y microconidios fue significativamente diferente entre los morfotipos, pero no entre las especies.

Palabras clave: marchitez; macroconidios; microconidios; clamidosporas; polifiálides

The genus Fusarium includes many filamentous fungi that are widely distributed all over the world. Several members of this genus cause diseases in plants, animals and humans. Different Fusarium species cause diseases in some of the most important crops, such as rice, maize, wheat, beans, soybeans, squash, melon and watermelon, among others (Smith, 2007).

Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) production in Mexico generates around US $300 million per year and the main watermelon producer is the state of Sonora. The economic benefits of watermelon cropping in Sonora exceed US $30 million a year (SIAP, 2017). However, watermelon fields in the state are frequently threatened by several fungal diseases.

Most research studies point to Fusarium oxysporum and F. solani as the main causes of death of watermelon plants by wilt and root rot. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum is considered the most important of the fungi that cause wilt in watermelon crops worldwide (Egel and Martyn, 2007; Zhou et al., 2010; Turóczi et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2014). Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae (races 1 and 2) is another species that causes wilt in watermelon plants, although with lower prevalence. Race 2 affects only watermelon fruit, in which it causes dry rot, but race 1 affects both mature fruits and plants, in which it causes dry rot and cortical stem rot, respectively (Boughalleb et al., 2005; Mehl and Epstein, 2007).

Recently, Rentería-Martínez et al. (2018) identified Fusarium falciforme (belonging to Fusarium solani species complex), F. brachygibbosum and F. oxysporum, as well as Rhizoctonia solani and Ceratobasidium sp., as fungi associated with wilt and root rot in watermelon plants grown in Sonora, Mexico.

Fusarium brachygibbosum has been identified as a pathogen in legumes (Tan et al., 2011), date palm plants (Al-Sadi et al., 2012), Euphorbia larica (Al-Mahmooli et al., 2013), Nerium oleander (Mirhosseini et al., 2014), Striga hermonthica (Rna et al., 2014), medicinal plants (Gashgari et al., 2016), almond trees (Stack et al., 2017), maize (Shan et al., 2017), olive trees (Trabelsi et al., 2017), sunflower (Xia et al., 2018) and sugar beet (Cao et al., 2018). According to these reports, F. brachygibbosum was identified through molecular techniques, and only a brief morphological description was included using the morphotype reported by Padwick (1945) as a reference in all the cases, but without considering the diversity of morphotypes of the specie.

According to Leslie et al. (2001), the different shapes of the macroconidia are essential for identifying many Fusarium species, but there are other useful traits that could be used to distinguish the species of a genus. Traditionally, Fusarium species have been identified based on their morphological characteristics, such as the shape and size of macro- and microconidia, and the absence or presence and shape of chlamydospores. The appearance, shape and pigmentation of the colonies, as well as their growth rates in different media, are also taken into consideration (Leslie and Summerell, 2006; Ismail et al., 2015). These findings highlight the importance of knowing which morphological traits can help identify the Fusarium species that cause watermelon plants to die in Sonora.

Based on the above, the objective of this study was to analyze and compare the morphological variability among Fusarium brachygibbosum, F. falciforme and F. oxysporum morphotypes identified as being the causal agents of wilt in watermelon plants grown in Sonora, Mexico, in order to establish the distinctive macro- and microscopic characteristics of these species.

Materials and methods

The sites and methodology used to sample plants showing symptoms, isolation, monosporic cultures, DNA extraction, as well as to do the molecular identification and conduct pathogenicity tests on the isolates following Koch’s postulates, were described and published by Rentería-Martínez et al. (2018). A total of 25 Fusarium falciforme isolates, five F. brachygibbosum isolates, and two F. oxysporum isolates were identified.

Morphotype classification. Morphotypes of each species were established based on the type of growth, mycelium color and culture medium pigmentation. Assessments were conducted on one isolate that was representative of each morphotype.

Morphology and growth rate of the colonies. The macroscopic characteristics of the colonies (mycelium growth rate, color of the colony and pigmentation) were evaluated in potato-dextrose-agar (PDA) medium. The growth rate of each isolate was determined by taking a disk 8 mm in diameter containing 7-day-old colonies in PDA and placing it in the middle of another dish containing PDA. The dishes were incubated at 27 °C and the colony’s diameter was measured in two perpendicular directions every day until the dish was completely covered by the culture. Five replicates of each isolate were evaluated. The morphology of the colonies and the aerial pigmentation of the mycelium were recorded (Nelson et al., 1983).

Analysis of microscopic characteristics. The different morphotypes were cultured in carnation leaf agar (CLA), according to the method of Fisher et al. (1982). To promote the formation of chlamydospores, soil-agar (SA) was used, according to the method of Klotz et al. (1988). The CLA and SA cultures were incubated under the same conditions: 25 °C, 12 h light/12 h darkness for two weeks.

Microscopic preparations on slides were observed using a compound light microscope (VELABTM). To observe and measure the size of the conidia, phialides and chlamydospores, pictures were taken at 40X and 100X, which were then analyzed using TSView software, version 6.2.4.5. The length and width of 50 macroconidia and 50 microconidia randomly selected from each isolate were measured.

Statistical analysis. Data on macroconidial and microconidial length and width were subjected to an analysis of variance (ANOVA) and media separation using Tukey’s test (α<0.05) and the JMP program v5.0.1a.

Results

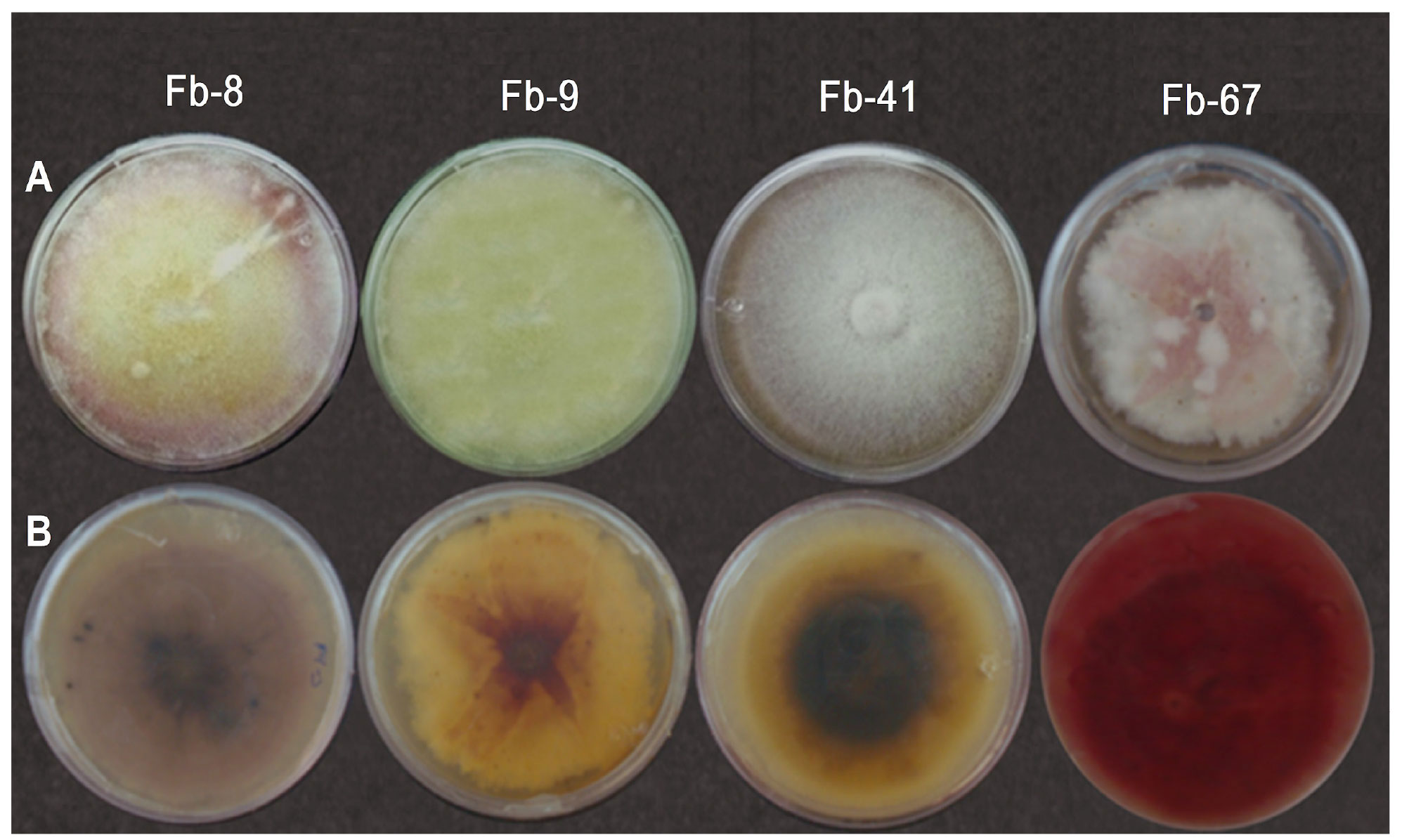

Morphotype classification and growth rate. The 25 F. falciforme isolates were grouped in three morphotypes (Ff-14, Ff-49 and Ff-50), the five F. brachygibbosum isolates in four morphotypes (Fb-8, Fb-9, Fb-41 and Fb-67), and the two F. oxysporum isolates in one morphotype (Fo-38). Table 1 shows the growth rates and macroscopic characteristics observed in F. brachygibbosum, F. falciforme and F. oxysporum morphotypes grown in PDA. Figure 1 shows the presence of the four F. brachygibbosum pathogenic morphotypes found in watermelon fields in Sonora.

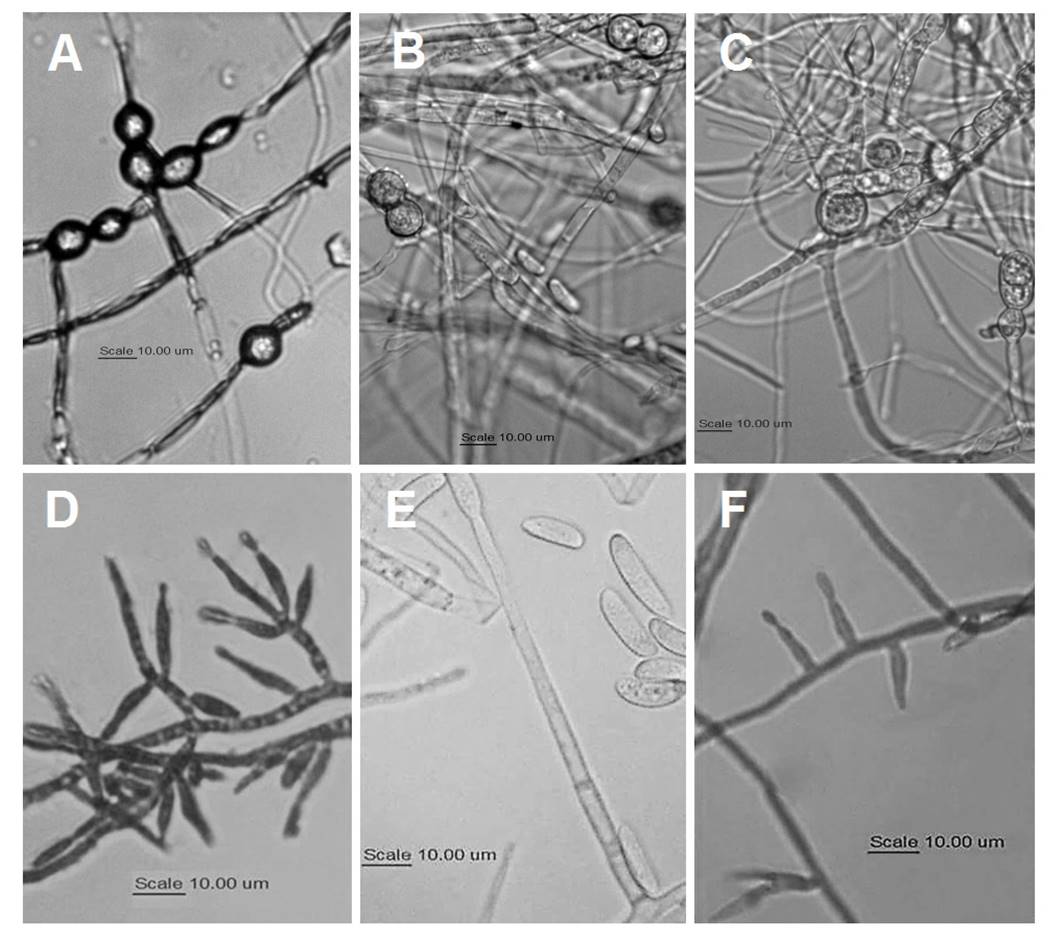

Microscopic characteristics. Table 2 summarizes the chlamydospores morphology and conidiogenic cells observed in isolates representative of each morphotype in the three species. In all cases, spherical, intercalary and terminal chlamydospores were observed, mainly singly and in pairs; however, the walls of the chlamydospores of F. brachygibbosum morphotypes (Figure 2A) are thicker, which seems to be a characteristic that distinguishes them from those of F. falciforme and F. oxysporum (Figure 2B-C). Regarding conidiogenic cells, F. falciforme morphotypes (Figure 2B) differ from the others because their monophialides are longer and thinner.

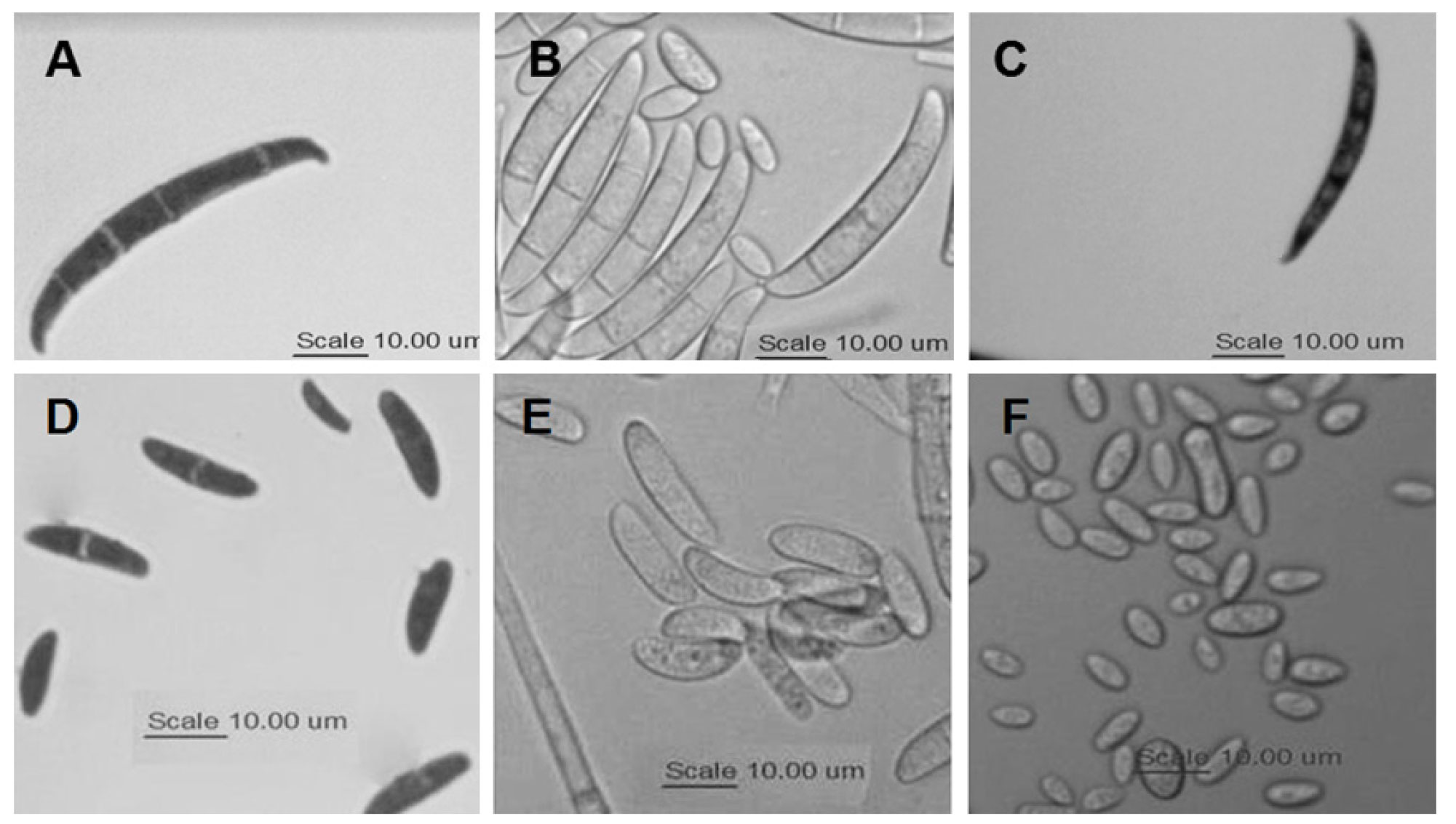

Table 3 shows a morphological description of the macroconidia and microconidia of isolates that are representative of each morphotype. There were some differences among the three species. The four F. brachygibbosum morphotypes had thin, straight macroconidia with three to five septa, the cells in the middle were slightly wide and the intermediate cells were curved towards the basal part. The apical cells were slightly hook-shaped, while the basal cells had a typical shape or were slightly foot-shaped (Figure 3). F. falciforme macroconidia were wide and straight, or slightly curved, but the ventral and dorsal planes were parallel along most of their length, the apical cells were rounded, while the basal cells were straight and cylindrical with a barely trimmed or round end (Figure 4B). The shape of F. oxysporum macroconidia was similar to that of F. brachygibbosum macroconidia, but their basal cells were pointed and lower in number, with a barely visible foot shape (Figure 4C).

Table 1. Growth rate on PDA and macroscopic characteristics of F. brachygibbosum, F. falciforme and F. oxysporum morphotypes pathogenic to watermelon.

| Velocidad de crecimientox | Morfología de las colonias | Pigmentacióny | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F. brachygibbosum | |||

| Fb-8 | 4.9 | Micelio aéreo, velloso de color blanco, tornándose amarillo y rosa con esporodoquios amarillos después de 2 semanas. | Café claro, con manchas café oscuro alrededor de los esporodoquios. |

| Fb-9 | 4.2 | Micelio aéreo, velloso de color amarillo, con esporodoquios color café después de 2 semanas. | Amarillo-naranja con el centro café rojizo en forma de estrella. Con manchas café oscuras alrededor de los esporodoquios. |

| Fb-41 | 4.8 | Micelio aéreo, velloso de color café claro, con esporodoquios café después de 2 semanas. | Centro café oscuro con anillos concéntricos menos café hacia afuera. Con manchas café claro alrededor de los esporodoquios. |

| Fb-67 | 4.6 | Micelio aéreo, velloso de color blanco al inicio. Tornándose rosa con el desarrollo esporodoquios amarillos después de 2 semanas. | Rojo intenso brillante en todo el fondo de la caja. |

| F. falciforme | |||

| Ff-14 | 4.1 | Micelio postrado de color beige. Crecimiento en anillos concéntricos, sin formación de esporodoquios. | Café claro con halos café oscuros debido al crecimiento en forma de anillo. |

| Ff-49 | 3.6 | Micelio postrado de color beige, sin formación de esporodoquios. | Café claro. |

| Ff-50 | 3.9 | Micelio postrado de color blanco, sin formación de esporodoquios. | Beige muy claro, cubriendo toda la caja. |

| F. oxysporum | |||

| Fo-38 | 3.4 | Micelio velloso de color blanco, el cual se torna purpura después de una semana. Sin formación de esporodoquios. | Púrpura en toda la caja. |

x mm/día / mm/day.

y Fondo de la caja Petri / Bottom of the Petri dish.

F. brachygibbosum microconidia were oval, sometimes ovoid, usually with one septum, rarely with two or none. F. oxysporum microconidia were elliptical, oval and kidney-shaped with no septa. F. falciforme had oval, ellipsoid and kidney-shaped microconidia with a truncated basal part, and some of them were pyriform and fusiform with one or two septa, or none (Table 3, Figure 4 D-F). Due to shape variability, it was not possible to observe differences among macroconidia from different species, and only the absence of septa in all F. oxysporum (Figure 4F) microconidia observed seems to be a distinctive trait.

Figure 1 Morphological characteristics of colonies of four Fusarium brachygibbosum morphotypes grown in PDA. A = Front B = bottom.

Table 2. Morphology of chlamydospores and conidiogenous cells F. brachygibbosum morphotypes, and isolates that were representative of F. falciforme and F. oxysporum grown in CLA.

| Forma de las clamidosporas | Tipo de células conidiógenas | |

|---|---|---|

| F. brachygibbosum | ||

| Fb-8 | Dobles. Intercalares y terminales. Pared gruesa. | Monofiálides cortas. Algunas polifiálides cortas. |

| Fb-9 | Sencillas. Intercalares. Pared gruesa. | Monofiálides cortas. Algunas polifiálides cortas. |

| Fb-41 | Sencillas. Intercalares. Pared gruesa. | Monofiálides cortas. Algunas polifiálides cortas. |

| Fb-67 | Sencillas y dobles. Intercalares y terminales. Pared gruesa. | Monofiálides cortas. Algunas polifiálides cortas. |

| F. falciforme | ||

| Ff-14 | Sencillas, dobles y en cadena. Intercalares y terminales. Pared mediana. | Monofiálides muy largas y algunas cortas. Pocas polifiálides. |

| Ff-49 | Sencillas y dobles. Intercalares y terminales. Pared de grosor medio o delgado. | Monofiálides muy largas y algunas cortas. Pocas polifiálides. |

| Ff-50 | Sencillas y dobles. Terminales. Pared de grosor medio o delgado. | Monofiálides muy largas abundantes. Pocas polifiálides. |

| F. oxysporum | ||

| Fo-38 | Sencillas y dobles. Intercalares y terminales. Pared de grosor medio o delgado. | Monofiálides cortas y escasa presencia de polifiálides. |

Figure 2 A-C: Morphology of chlamydospores of A = F. brachygibbosum; B = F. falciforme; and C = F. oxysporum. D-F: Morphology of conidiogenous cells: D = polyphialides and monophialides of F. brachygibbosum, E = monophialides of F. falciforme, and F = monophialides of F. oxysporum.

Table 3. Morphology of macroconidia and microconidia of F. brachygibbosum, F. falciforme and F. oxysporum morphotypes pathogenic to watermelon grown in CLA.

| Forma de macroconidios | Forma de microconidios | |

|---|---|---|

| F. brachygibbosum | ||

| Fb-8 | Delgadas, largas y rectas. Células centrales ligeramente anchas y curvadas hacia la parte basal. Células apicales con ligera forma de gancho y células basales con ligera forma de pie. Tres o cuatro septos. | Ovales y algunas ovoides. Con uno y escasamente con ninguno o con dos septos. |

| Fb-9 | Delgadas, largas y rectas. Células centrales ligeramente anchas y curvadas hacia la parte basal. Células apicales con ligera forma de gancho y células basales con típica forma de pie. Tres a cinco septos. | Ovales y algunas ovoides. Con uno y escasamente con ninguno o con dos septos. |

| Fb-41 | Delgadas, largas y rectas. Células centrales ligeramente anchas y curvadas hacia la parte basal. Células apicales con ligera forma de gancho y células basales con típica forma de pie. Tres a cinco septos. | Ovales y algunas ovoides. Con uno y escasamente con ninguno o con dos septos. |

| Fb-67 | Delgadas, largas y rectas. Células centrales ligeramente anchas y curvadas hacia la parte basal. Células apicales con ligera forma de gancho y células basales con ligera forma de pie. Tres a cinco septos. | Ovales y algunas ovoides. Con uno y escasamente con ninguno o con dos septos. |

| F. falciforme | ||

| Ff-14 | Anchas y rectas. Ligeramente curvadas con el plano ventral y dorsal paralelo en la mayor parte de su longitud. Células apicales redondeadas. Células basales rectas y cilíndricas, con extremos apenas recortados o redondeados. Con tres a seis septos. | Ovales, elipsoides, reniformes y fusiformes. Con la parte basal truncada. Con ningún o con un septo. |

| Ff-49 | Anchas y rectas. Ligeramente curvadas con el plano ventral y dorsal paralelo en la mayor parte de su longitud. Células apicales redondeadas. Células basales rectas y cilíndricas, con extremos apenas recortados. Con tres a seis septos. | Ovales, elipsoides y reniformes. Con cero, uno o dos septos. |

| Ff-50 | Anchas y rectas. Ligeramente curvadas con el plano ventral y dorsal paralelo en la mayor parte de su longitud. Células apicales redondeadas. Células basales rectas y cilíndricas, con extremos apenas recortados. Con cuatro a seis septos. | Ovales, elipsoides, reniformes y ocasionalmente piriformes. Con cero, uno y ocasionalmente dos septos. |

| F. oxysporum | ||

| Fo-38 | Cortas a medianas y esbeltas. Rectas o ligeramente curvadas. Células apicales cónicas con ligera forma de gancho y células basales en forma puntiaguda. Tres o cuatro septos. | Ovales típicas, elípticas y forma de riñón. Sin septos. |

Figure 3 Morphology of macroconidia of four F. brachygibbosum morphotypes. A = slightly hook-shaped apical cells; and B = slightly foot-shaped basal cells (Fb-8 and Fb-67) and typical foot-shaped cells (Fb-9 and FB-41).

Table 4 shows the average length and width of the macroconidia, according to the number of septa and the average of 50 cells. The statistical analysis detected significant differences in the average length and width of the macroconidia among the isolates, but due to the variability in size within the species, it was not possible to observe the differences between them. Macroconidia with Fb-8 and Fb-9 morphotypes had no significant size differences compared to F. oxysporum Fo-38 morphotypes. No significant differences were detected in the size of Fb-41, Fo-39 and Ff-49 macroconidia, nor among Fb-67, Ff-50 and Ff-14 macroconidia.

Figure 4 Morphology of macroconidia and microconidia of three Fusarium species pathogenic to watermelon. A = mac roconidia of F. brachygibbosum, B = macroconidia of F. falciforme, and C) macroconidia of F. oxysporum. D = macroconidia of F. brachygibbosum, E = microconidia of F. falciforme, and F) microconidia of F. oxysporum.

Table 5 shows the average length and width of the macroconidia, according to the number of septa and the average of 50 cells. In general, significant differences were detected in the size of the macroconidia among isolates but not among species. The Fb-41, Fb-67 and Fb-9 morphotypes had the longest microconidia, while Fb-8 had the shortest.

Table 4. Size of macroconidia of F. brachygibbosum, F. falciforme and F. oxysporum isolates pathogenic to watermelon grown in CLA, according to the number of septa.

| Tamaño de macroconidios (μm) x | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Número de septos | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Promedio y | ||||||||||||||||

| F. brachy-gibbosum | Largo | Ancho | Largo | Ancho | Largo | Ancho | Largo | Ancho | Largo | Ancho | ||||||||||

| Fb-8 | 30.74 ± 4.49 | 3.29 ± 0.35 | 35.13 ± 3.79 | 3.18 ± 0.35 | - | - | - | - | 31.45 ± 4.09F | 3.28 ± 0.35E | ||||||||||

| Fb-9 | 34.16 ± 3.72 | 3.58 ± 0.52 | 38.98 ± 2.16 | 4.04 ± 0.30 | 42.34 ± 2.93 | 3.54 ± 0.13 | - | - | 35.52 ± 4.35 E | 3.65 ± 0.51D | ||||||||||

| Fb-41 | 35.52 ± 4.49 | 3.70 ± 0.55 | 38.25 ± 5.08 | 3.85 ± 0.64 | 39.46 ± 9.50 | 4.13 ± 0.51 | - | - | 37.04 ± 5.33DE | 3.80 ± 0.59D | ||||||||||

| Fb-67 | 40.01 ± 7.19 | 4.28 ± 0.37 | 45.04 ± 5.65 | 4.32 ± 0.47 | 50.08 ± 1.54 | 4.61 ± 0.28 | - | - | 43.04 ± 6.97AB | 4.33 ± 0.42C | ||||||||||

| F. falci- forme | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ff-14 | 40.11 ± 0.65 | 4.69 ± 0.11 | 43.55 ± 1.16 | 5.03 ± 0.10 | 45.90 ± 0.68 | 5.35 ± 0.08 | 47.3 ± 0.23 | 5.64 ± 0.10 | 44.04 ± 0.82A | 5.13 ± 0.10A | ||||||||||

| Ff-49 | 37.60 ± 1.59 | 4.47 ± 0.28 | 39.10 ± 1.46 | 4.82 ± 0.20 | 40.67 ± 1.30 | 4.69 ± 0.42 | 43.30 ± 1.55 | 5.07 ± 0.36 | 39.90 ± 1.45CD | 4.77 ± 0.29B | ||||||||||

| Ff-50 | - | - | 38.74 ± 0.57 | 3.80 ± 0.16 | 41.04 ± 0.92 | 3.74 ± 0.10 | 43.45 ± 0.62 | 3.88 ± 0.06 | 40.56 ± 0.71BCD | 3.83 ± 0.12D | ||||||||||

| F. oxys-porum | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Fo-38 | 32.22 ± 3.07 | 3.32 ± 0.47 | 35.48 ± 2.84 | 3.26 ± 0.31 | - | - | - | - | 33.26 ± 3.00E | 3.30 ± 0.42E | ||||||||||

x Media ± SD. Letras diferentes indican diferencia significativa (p<0.05) / Means ± SD. Different letters indicate a significant difference (p< 0.05).

y Promedio de 50 células (Average of 50 cells) / Average of 50 cells.

- No se observaron suficientes células para su medición (No observed sufficient cells to measure) / Not enough cells observed.

Discussion

Padwick (1945) stated that F. brachygibbosum grows in PDA and develops an abundance of aerial white mycelia, pinkish tone, and blood-red color in the agar; its microconidia are typically ovoid to fusiform, or slightly curved when they have septa, with one, two, three or no septa. Hyperbolically curved macroconidia are finely dispersed over the agar surface; they have wide central cells and 0-5 septa. Sharp apical cells and slightly sharp basal cells have a typical foot-like shape; terminal and intercalary chlamydospores, single or in chains, are usually unicellular and globose, occasionally with two smooth and granular cells. This description is in agreement with the four F. brachygibbosum morphotypes that were found in this study, but the color of the colony and the medium coincides only with the color of Fb-67 and not with the color of Fb-8, Fb-9 and Fb-41.

In general, the type of mycelium, the color of the colonies and the culture medium, as well as the morphology of the macro- and microconidia observed in the most recent F. brachygibbosum studies (Al-Sadi et al., 2012; Mirhosseini et al., 2014; Renteria-Martinez et al., 2015; Stack et al., 2017; Shan et al., 2017; Xia et al., 2018) correspond to the morphotype described by Padwick (1945). All these studies found white colonies that turned yellow with pink or orange tones, and stained the PDA medium bright red. When they were grown in CLA, the macroconidia had thick walls, a bulky center and slightly curved ends (attenuated hook), and a typical foot-like or slightly foot-shaped basal cell; most of them had 4-5 septa.

Table 5. Size of microconidia of F. brachygibbosum isolates pathogenic to watermelon and pathogenic isolates that were representative of F. solani and F. oxysporum grown in CLA, according to the number of septa.

| Tamaño de microconidios (μm)x | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Número de septos | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | Promedioy | |||||||||||||||

| F. brachygibbosum | Largo | Ancho | Largo | Ancho | Largo | Ancho | Largo | Ancho | ||||||||||

| Fb-8 | - | - | 13.79 ± 1.84 | 3.95 ± 0.46 | - | - | 13.79 ± 1.84b | 3.95 ± 0.46C | ||||||||||

| Fb-9 | - | - | 7.15 ± 0.43 | 2.40 ± 0.64 | - | - | 7.15 ± 0.43b | 2.40 ± 0.64A | ||||||||||

| Fb-41 | - | - | 18.78 ± 2.92 | 3.81 ± 0.47 | - | - | 18.78 ± 2.92a | 3.81 ± 0.47A | ||||||||||

| Fb-67 | - | - | 17.73 ± 3.67 | 3.91 ± 2.53 | - | - | 17.73 ± 3.67a | 3.91 ± 2.53A | ||||||||||

| F. falciforme | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ff-14 | 11.42 ± 2.29 | 3.21 ± 0.34 | 11.06 ± 2.39 | 3.15 ± 0.35 | - | - | 11.18 ± 2.36c | 3.17 ± 0.35A | ||||||||||

| Ff-49 | 9.41 ± 0.86 | 2.94 ± 0.63 | 10.61 ± 0.88 | 3.85 ± 0.51 | 11.18 ± 1.02 | 4.91 ± 0.47 | 10.29 ± 0.89cd | 3.73 ± 0.55AB | ||||||||||

| Ff-50 | 10.26 ± 1.10 | 3.68 ± 0.53 | 11.99 ± 0.45 | 4.18 ± 0.25 | - | - | 11.17 ± 0.75c | 3.95 ± 0.38A | ||||||||||

| F. oxysporum | ||||||||||||||||||

| Fo-38 | 8.56 ± 1.40 | 3.05 ± 0.56 | - | - | - | - | 8.56 ± 1.40de | 3.05 ± 0.56BC | ||||||||||

x Media ± SD. Letras diferentes indican diferencia significativa (p< 0.05) / Means ± SD. Different letters indicate a significant difference (p< 0.05).

y Promedio de 50 células (Average of 50 cells) / Average of 50 cells.

-No se observaron suficientes células para su medición (No observed sufficient cells to measure) / Not enough cells observed.

The F. oxysporum morphotype developed white aerial mycelium that turned purple after a week in PDA, a result similar to that described by Kleczewski and Egel (2011) regarding F. oxysporum f.sp. niveum race 1, but with no sporodochia formation. When cultured in CLA, the characteristics of the chlamydospores, conidiogenic cells, macroconidia and microconidia were in agreement with the results obtained by Leslie and Summerell (2006) for the species.

The type of growth colonies in PDA makes it possible to distinguish between F. brachygibbosum (aerial) and F. falciforme (prostrate) morphotypes. The presence of long and thin monophialides observed in F. falciforme morphotypes (Summerbell and Schroers, 2002) is a characteristic that allows differentiating them from F. brachygibbosum and F. oxysporum, which develop shorter monophialides. The shape of F. falciforme macroconidia is another trait that distinguishes it from the other species. Similar to the results obtained by Chehri et al. (2015), macroconidia of this species were polyseptate, wide and straight or slightly curved, with round apical cells and basal cells with slightly trimmed ends.

The color developed in the agar, the type of conidiogenic cells, as well as macroconidial morphology and size, can cause F. brachygibbosum to be mistakenly identified as F. oxysporum, which is more common in most of the crops in Sonora, but the morphology of the chlamydospores, specifically the thickness of their walls, may be a distinctive characteristic that allows differentiating the two species. The morphology of F. brachygibbosum chlamydospores is in agreement with the results obtained by Cao et al. (2018). Another characteristic that differs among these species is the lack of septa in F. oxysporum microconidia, while F. brachygibbosum had mostly microconidia with one septum.

The variability in macroconidia and microconidia size among morphotypes of the same species did not allow differentiating among the Fusarium species.

F. brachygibbosum conidia of different sizes have been reported (Xia et al., 2018; Shan et al., 2017; Mirhosseini et al., 2014; Al-Mahmooli et al., 2013) and, in most cases, they have been shorter than the ones observed in this study. The size of F. falciforme macroconidia was similar to the size reported by Chehri et al. (2015). Also, the morphology and size of F. oxysporum macroconidia were in agreement with the results obtained by Chehri et al. (2011).

Conclusions

Some characteristics, such as the thickness of chlamydospore walls, macroconidia morphology, type of conidiogenic cells and the presence or absence of septa in microconidia can be distinctive and useful for identifying F. brachygibbosum, F. falciforme and F. oxysporum that are pathogenic to watermelon plants grown in Sonora, Mexico. However, the identified morphologies need to be corroborated through molecular analysis.

Literatura citada

Al-Mahmooli IH, Al-Bahri YS, Al-Sadi AM and Deadman ML. 2013. First report of Euphorbia larica dieback caused by Fusarium brachygibbosum in Oman. Plant Disease 97(5): 687. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-09-12-0828-PDN [ Links ]

Al-Sadi AM, Al-Jabri AH, Al-Mazroui SS and Al-Mahmooli IH. 2012. Characterization and pathogenicity of fungi and oomycetes associated with root diseases of date palms in Oman. Crop Protection 37(1): 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2012.02.01 [ Links ]

Boughalleb N, Armengol J and Mahjoub, ME. 2005. Detection of races 1 and 2 of Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae and their distribution in watermelon fields in Tunisia. Journal of Phytopathology 153:162-168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0434.2005.00947.x [ Links ]

Cao S, Yang N, Zhao C, Liu J, Han C and Wu X. 2018. Diversity of Fusarium species associated with root rot of sugar beet in China. Journal of General Plant Pathology 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10327-018-0792-5 [ Links ]

Chehri K, Salleh B, Yli-Mattila T, Reddy KRN, Abbasi S. 2011. Molecular characterization of pathogenicFusariumspecies in cucurbit plants from Kermanshah province, Iran. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences.18(4):341-351. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2011.01.007. [ Links ]

Chehri K, Salleh B and Zakaria L. 2015. Morphological and phylogenetic analysis of Fusarium solani species complex in Malaysia. Microbial ecology. 69(3): 457-471. DOI 10.1007/s00248-014-0494-2 [ Links ]

Egel DS and Martyn RD. 2007. Fusarium wilt of watermelon and other cucurbits. The Plant Health Instructor. DOI: 10.1094/PHI-I-2007-0122-01 [ Links ]

Fisher NL, Burgess LW, Toussoun TA and Nelson PE. 1982. Carnation leaves as a substrate and for preserving cultures of Fusarium species. Phytopathology 72:151-153. DOI: 10.1094/Phyto-72-151 [ Links ]

Gashgari R, Gherbawy Y, Ameen F and Alsharari S. 2016. Molecular characterization and analysis of antimicrobial activity of endophytic fungi from medicinal plants in Saudi Arabia. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology 9(1): e26157. DOI: 10.5812/jjm.26157 [ Links ]

Ismail MA, Abdel-Hafez SI, Hussein N A and Abdel-Hameed NA. 2015. Contributions to the genus Fusarium in Egypt with dichotomous keys for identification of species. 1st. ed. Tmkarpiński Publisher Suchy Las, Poland. 179 pp. Disponible en línea: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mady_Ismail/publication/321344925_FUSARIUM_IN_EGYPT_WITH_DICHOTOMOUS_KEYS_FOR_IDENTIFICATION_OF_SPECIES_Contributions_to_the_genus_Fusarium_in_Egypt_with_dichotomous_keys_for_identification_of_species/links/5a1de0980f7e9b9d5effb25e/FUSARIUM-IN-EGYPT-WITH-DICHOTOMOUS-KEYS-FOR-IDENTIFICATION-OF-SPECIES-Contributions-to-the-genus-Fusarium-in-Egypt-with-dichotomous-keys-for-identification-of-species.pdf [ Links ]

Kleczewski NM and Egel DS. 2011. A diagnostic guide for Fusarium wilt of watermelon. Plant Health Progress. doi:10.1094/PHP-2011-1129-01-DG [ Links ]

Klotz LV, Nelson PE and Toussoun TA. 1988. A medium for enhancement of chlamydospores formation in Fusarium species. Mycologia 80:108-109. DOI: 10.2307/3807500 [ Links ]

Leslie JF, Zeller KA and Summerell BA. 2001. Icebergs and species in populations of Fusarium. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 59(3):107-117. doi:10.1006/pmpp.2001.0351, [ Links ]

Leslie JF and Summerell BA. 2006. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual. 1st. ed. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, London. Victoria, Australia. 388 pp. [ Links ]

Mehl HL and Epstein L. 2007. Identification of Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae race 1 and race 2 with PCR and production of disease-free pumpkin seeds. Plant Disease 91(10):1288-1292. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-91-10-1288 [ Links ]

Mirhosseini HA, Babaeizad V and Hashemi L. 2014. First report of Fusarium brachygibbosum causing leaf spot on oleander in Iran. Journal of Plant Pathology. 96(2): 431-439. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4454/JPP.V96I2.002 [ Links ]

Nelson PE, Toussoun TA, Marasas WFO (1983) Fusarium species: An Illustrated manual for identification. Pennsylvania State University Press. University Park. 193 pp. [ Links ]

Padwick GW. 1945. Notes on Indian fungi III. Mycological Papers. 12:1-15. [ Links ]

Rentería-Martínez ME., Meza-Moller A, Guerra-Camacho MA, Romo-Tamayo F, Ochoa-Meza A and Moreno-Salazar SF. 2015. First report of watermelon wilting caused by Fusarium brachygibbosum in Sonora, Mexico. Plant Disease 99(5):729. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-10-14-1073-PDN [ Links ]

Rentería-Martínez ME, Guerra-Camacho MA, Ochoa-Meza A, Moreno-Salazar SF, Varela-Romero A, Gutiérrez-Millán LE, and Meza-Moller AC. 2018. Multilocus phylogenetic analysis of fungal complex associated with root rot watermelon in Sonora, Mexico. Mexican Journal of Phytopatholgy. 36(2):233-255. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18781/R.MEX.FIT.1710-1 [ Links ]

Rna AG, Babikar A, Dagash Y, Elhussein AA, Elhalim TSA and Babikar AGT. 2014. Fusarium brachygibbosum a plausible candidate for deployment as a bioagent for Striga hermonthica management in Sorghum. Third Conference of Pests Management in Sudan February 3-4, 2014 CPRC-ARC, Wad Medani (Sudan). http://www.arc-cprc.sd/weedscience.pdf [ Links ]

Shan LY, Cui WY, Zhang DD, Zhang J, Ma NN, Bao YM, Dai XF and Guo W. 2017. First report of Fusarium brachygibbosum causing maize stalk rot in China. Plant Disease 101(5): 837. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-10-16-1465-PDN [ Links ]

Smith, SN. 2007. An overview of ecological and habitat aspects in the genus Fusarium with special emphasis on the soil-borne pathogenic forms. Plant Pathology Bulletin 16:97-120. http://140.112.183.156/pdf/16-3/p097-120.pdf [ Links ]

Stack AJ, Yaghmour MA, Kirkpatrick SC, Gordon TR and Bostock RM. 2017. First report of Fusarium brachygibbosum causing cankers in cold-stored, bare-root propagated almond trees in California. Plant Disease 101(2): 390-390. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-06-16-0929-PDN [ Links ]

Summerbell RC and Schroers HJ. 2002. Analysis of phylogenetic relationship of Cylindrocarpon lichenicolaandAcremonium falciformeto theFusarium solani species complex and a review of similarities in the spectrum of opportunistic infections caused by these fungi. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40(8): 2866-2875. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.8.2866-2875.2002 [ Links ]

Tan DC, Flematti GR, Ghisalberti EL, Sivasithamparam K, Chakraborty S, Obanor F and Barbetti, MJ. 2011. Mycotoxins produced by Fusarium species associated with annual legume pastures and ‘sheep feed refusal disorders’ in Western Australia. Mycotoxin research 27(2):123-135. doi: 10.1007/s12550-010-0085-0 [ Links ]

Trabelsi R, Sellami H, Gharbi Y, Krid S, Cheffi M, Kammoun S, Dammak M, Mseddi A, Gdoura R and Ali TM. 2017. Morphological and molecular characterization of Fusarium spp. associated with olive trees dieback in Tunisia. Biotech 7:28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0587-3 [ Links ]

Turóczi GV, Posta K, Badenszky L and Bán R. 2011. Fusarium wilt of water melon caused by Fusarium solani in Hungary. Plant Breeding and Seeds Science 63:23-28. DOI: 10.2478/v10129-011-0012-3 [ Links ]

Xia B, Hu J, Zhu X, Liang Y, Ren X, Wu Y and Chen D. 2018. First report of sunflower broomrape wilt caused by Fusarium brachygibbosum in China. Plant Disease (Accepted) https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-12-17-1939-PDN [ Links ]

Zhang M, Xu JH, Liu G, Yao XF, Li PF and Yang XP. 2014. Characterization of the watermelon seedling infection process by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum. Plant Pathology. 64:1076-1084. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12355 [ Links ]

Zhou XG, Everts KL and Bruton BD. 2010. Race 3, a new and highly virulent race of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum causing Fusarium wilt in watermelon. Plant Disease 94(1):92-98. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-94-1-0092 [ Links ]

Received: August 04, 2018; Accepted: September 21, 2018

text in

text in