Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Nova tellus

versão impressa ISSN 0185-3058

Nova tellus vol.28 no.1 Ciudad de México Jun. 2010

Artículos

A New Reading of one of the Earliest Christian Letters Outside the New Testament and the Dangers of Early Christian Communities in Egypt1

Una nueva lectura de una de las más antiguas cartas cristianas fuera del Nuevo Testamento y los peligros para las primitivas comunidades cristianas en Egipto

Ilaria L. E. Ramelli

Università Cattolica del Santo Cuore. Correo electrónico: ilaria.ramelli@virgilio.it.

Recepción: 18 de septiembre de 2009.

Aceptación: 27 de abril de 2010.

Abstract

The letter of Ammonius to Apollonius, preserved in an Oxyrhynchus papyrus and datable to the end of the I or the beginning of the n century AD, contains a superlinear stroke over the X of the initial XAIPEIN , which is the sign of a nomen sacrum that, together with many other clues in this epistolê kekhiasmenê, points to the Christianity of the writer and the addressee. In this new framework, many details of the letter become intelligible and the whole document, with an emphasis on the necessity of a circumspect behaviour and the use of a cryptic communication code, attests to the critical situation of the Christian communities in those days, when Christianity was a superstitio illicita and Christians had to try not to be denounced. I propose an analysis of the letter in this light: many aspects in its language, lexical choices, and rhetoric are telling. The new Christian reading of this letter allows us to recover one of the earliest Christian letters known and provides precious documentation of the birth of Christianity in Egypt, perhaps in Alexandria itself, from which the "Secret Gospel of Mark" also stems.

Keywords: Alexandria, papyrus letters, Christogram/Staurogram, Clement, Secret Gospel of Mark, arly Christianity, epistolê kekhiasmenê, Christian Communities in Egypt, nomina sacra.

Resumen

La carta de Amonio a Apolonio, conservada en un papiro de Oxirrinco que se puede datar hacia finales del siglo i o inicios del siglo n d. C., presenta un trazo horizontal encima de la X del XAIPEIN inicial, que es la marca de un nomen sacrum que, junto con muchas otras claves de esta epistolê kekhiasmenê, apunta al carácter cristiano tanto del escritor como del destinatario. En este nuevo marco, muchos detalles de la carta se vuelven inteligibles y el documento entero, con un énfasis en la necesidad de un comportamiento circunspecto y en el uso de un código comunicativo críptico, da testimonio de la situación crítica de las comunidades cristianas de aquellos días, cuando el cristianismo era una superstitio illicita y los cristianos tenían que tratar de no ser denunciados. Propongo un análisis de la carta bajo esta luz: muchos aspectos de su lenguaje, de sus elecciones léxicas y de su retórica resultan reveladores. La nueva lectura cristiana de esta carta nos permite recuperar una de las más antiguas cartas cristianas conocidas y proporciona una documentación preciosa sobre el nacimiento del cristianismo en Egipto, quizá en la misma Alejandría, de la que proviene también el "Evangelio secreto de Marcos".

Palabras clave: Alejandría, papiro, cartas, Cristograma/Estaurograma, Clemente, Evangelio secreto de Marcos, Cristianismo primitivo, epistolê kekhiasmenê, comunidades cristianas en Egipto, nomina sacra.

To the memory of Orsolina Montevecchi

(† 1st February 2009 at 97)

The letter of Ammonius to Apollonius, preserved in an Oxyrhynchus papyrus,2 was written by one single hand, in a clear and semi-literary fashion and, from the palaeographical point of view, is datable to the end of the first or the beginning of the second century A.D., and probably came from Alexandria.3 It contains a superlinear horizontal stroke, very clearly visible from the examination of the papyrus, over the X of the initial word of greetings, XAIPEIN , which is probably the sign of a nomen sacrum, that of Christ.4 At that time, such abbreviations for nomina sacra were just beginning to be used;5 this would be one of the very first attestations. Indeed, a notable parallel for this same period may be a leather fragment which was recently discovered in a cave in Wadi Murabba'at: it stems from the end of the first or the beginning of the second century —just like Ammonius's letter— and seems to contain the first attestation of Christ's monogram.6

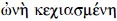

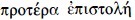

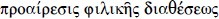

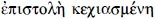

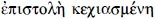

This remarkable element, which also explains the reason for a cryptical reference to an  , together with many other clues, which I shall point out, suggests that the writer and the addressee were Christians. This letter was first published by P. J. Parsons in 1974 in P. Oxy. XLII 3057, then it was republished by Llewelyn and Kearsley in Volume 6 of the New Documents Illustrating Early Christianity7 and I myself have offered an edition and translation, with commentary.8 This is the transcription (in which I preserve the original division of the lines) and my new English translation of the letter:

, together with many other clues, which I shall point out, suggests that the writer and the addressee were Christians. This letter was first published by P. J. Parsons in 1974 in P. Oxy. XLII 3057, then it was republished by Llewelyn and Kearsley in Volume 6 of the New Documents Illustrating Early Christianity7 and I myself have offered an edition and translation, with commentary.8 This is the transcription (in which I preserve the original division of the lines) and my new English translation of the letter:

[recto:] Ammonius to his brother Apollonius: greetings! [

]

I received the letter marked with the X sign [

],9 the mantel carrier, the travel mantels, and the inexpensive pipes. And, as for the travel mantels, I did not receive them as old, but, if possible, better than the new ones, thanks to (your) intention [

]. But I do not want, brother, that you oppress me with your continual acts of kindness [

], because I cannot return them; we should think that we have offered you only this: the intention [

] to demonstrate our affection [

].

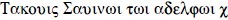

On the other hand, I exhort you, brother, not to concern yourself any more about the key of the one-room apartment: for I do not want that you, brothers, make any difference between me and another person.10

Indeed, I pray that concord and reciprocal love [

] remain among you, that you may not be an object of malevolent voices, and may both be like us [sc. that what has happened to us may not happen to you as well]. For my experience induces me to urge you to remain in peace without giving others any chance against you. Thus, please, endeavour to do this also for my sake, doing something for which I would be grateful [

] in that which you certainly recognize as good [

].

If you receive all the wool from Salvius, and it pleases you, write this to me in your reply; indeed, in my former letter I wrote you funny things, which you will admit.11 For my soul becomes serene whenever your name is present, and this although it is not accustomed to be tranquil, because of what is happening [

], but it endures [

].

I, Leonas,12 greet you, o master, and all of your household / community. Be well, o most honourable [

].

[verso:] To Apollonius, son of Apollo, inspector (?) [

] brother.

Many problems arise with the translation and, even more, with the interpretation of this letter. Parsons,13 after offering a few parallels in thought between this and two later Christian letters,14 observes that "The date of POxy 3057 rests entirely on the hand-writing. Either this paleographical date is too early ... or this letter is the earliest Christian document surviving in Egypt". The paleographical date is clear, and the possible Christian character of the letter is no reason to suppose that this date must be too early. Moreover, the presence of ascript iota in this letter, in the names that appear in the initial greetings and in the final ones (whereas iota is entirely omitted in verbal forms) confirms the early dating proposed by Parsons himself.

So, why was Parsons so full of doubts concerning the date that he himself had established on firm paleographical ground? Because he sensed —albeit offering very scarce proofs— that this letter might be Christian, and supposed that this automatically must imply a late dating.

In addition to Parsons, other scholars studied this letter, immediately after its first publication, among whom the late Orsolina Montevecchi in a very brief note in 1975 (Aegyptus 55, p. 302), in which she analyzed some formal details therein, such as the passage from the appellative "brother" to "lord", according to an alternative reading and rendering which I have discussed in a note to my translation. In 1984 Stanton studied the theme of fraternity and reciprocal love in this letter,15 and rightly warned that the presence of this theme per se is not enough to establish that this letter is Christian. And Judge's remarks are on the same line.16 Hemer17 stated that there are no explicit signs of Christianity, and Llewelyn18 prudently thinks that "the letter gives no indication that the correspondents were Christians, but equally no evidence stands in the way of its being so accepted".

None of these scholars considered the presence of the superlinear stroke over the X of the initial XAIPE, which may be a particular, cryptical mark of a nomen sacrum, and the pun with the expression  , which strongly reinforce the probability that this letter is Christian, one of the earliest Christian letters outside the New Testament.19 Indeed, this letter does not seem to have been studied again at depth, until the double contribution by Montevecchi and myself in 2000,20 and of myself in 2001,21 which adduced important evidence in order to ascribe this letter to a Christian author (and a Christian recipient). Our proposal also allows for a satisfactory interpretation —so far missing— of the reference to an

, which strongly reinforce the probability that this letter is Christian, one of the earliest Christian letters outside the New Testament.19 Indeed, this letter does not seem to have been studied again at depth, until the double contribution by Montevecchi and myself in 2000,20 and of myself in 2001,21 which adduced important evidence in order to ascribe this letter to a Christian author (and a Christian recipient). Our proposal also allows for a satisfactory interpretation —so far missing— of the reference to an  , formerly sent to Ammonius, probably by Apollonius. This syntagm is a unicum and has presented scholars with remarkable difficulties. The perfect participle derives from

, formerly sent to Ammonius, probably by Apollonius. This syntagm is a unicum and has presented scholars with remarkable difficulties. The perfect participle derives from  , which means "I mark with a X form", that is, with a crossed sign; this is attested for example in Diodore II 58. In the medical field, the verb was used to indicate the act of making an incision which had the form of a X (Oribasius 44, 20, 31). The verb also had a philological meaning, as is attested for example by scholia to Sophocles and Euripides; the meaning was "I mark with a X sign" in order to call attention to a specific passage or to mark a spurious verse. Of course, neither the medical nor the philological meaning are probable in the case of the letter between friends to which Ammonius refers.22

, which means "I mark with a X form", that is, with a crossed sign; this is attested for example in Diodore II 58. In the medical field, the verb was used to indicate the act of making an incision which had the form of a X (Oribasius 44, 20, 31). The verb also had a philological meaning, as is attested for example by scholia to Sophocles and Euripides; the meaning was "I mark with a X sign" in order to call attention to a specific passage or to mark a spurious verse. Of course, neither the medical nor the philological meaning are probable in the case of the letter between friends to which Ammonius refers.22

Papyri usually mention, for instance, an  , a contract cancelled by means of a series of signs in the form of a X, or else with one big X, in order to indicate that it was annulled or fulfilled. Known attestations of this expression in papyri are at least seven, six of which dating to the late first century A.D. and one to the second, thus all very close to our letter from the chronological point of view. These are:

, a contract cancelled by means of a series of signs in the form of a X, or else with one big X, in order to indicate that it was annulled or fulfilled. Known attestations of this expression in papyri are at least seven, six of which dating to the late first century A.D. and one to the second, thus all very close to our letter from the chronological point of view. These are:

1) P. Oxy. II 266, 15, from A.D. 96, contemporary with our letter: this is a dowry contract that was cancelled;

2) P. Oxy. X 1282, 35, from A.D. 85 d.C., again contemporary with our letter; here, too, the expression refers to the cancellation of an act;

3) PSI XII 1235, 21, also from the first century A.D., where the question is of a chirographic document concerning a bank receipt which involved a general and a library functionary; this was annulled in that the payment had taken place;

4) PTurner 1, 17, from Oxyrhynchus, from A.D. 69, and also roughly contemporary with our letter; this is a cancelled contract;

5) PYale I 63, 11, from Oxyrhynchus, from A.D. 64, likewise roughly contemporary with Ammonius' letter; it deals with a cancelled chirographic document;

6) SB VIII 9765, 16, from Oxyrhynchus, from A.D. 81 or shortly later, and therefore contemporary with Ammonius' letter; this too is an invalidated contract;

7) SB XVIII 13122, 7, of uncertain provenance, dating to the second century A.D.

The eighth occurrence of  is in Ammonius' letter, but in reference to another, previous private letter between friends, probably a reply to a previous letter by Ammonius himself (which Ammonius mentions here as well as

is in Ammonius' letter, but in reference to another, previous private letter between friends, probably a reply to a previous letter by Ammonius himself (which Ammonius mentions here as well as  , and not to a contract or any act.

, and not to a contract or any act.

Apart from Ammonius' letter, there is no other known occurrence of the expression  . Parsons23 observed that in our letter this participle may indicate the cancellation of a contract, in which case the X signs could be many, and reciprocally joined so as to create a reticulum; it may also indicate that the writer wished to fill in a blank line in order to prevent non-authorzed additions (e.g. in P.Mich. inv. 239). However, Parsons himself recognized that in the case of a private letter between friends who esteemed and loved each other —and moreover were extremely generous with each other, I would add— this possibility is very remote and is probably to be ruled out.

. Parsons23 observed that in our letter this participle may indicate the cancellation of a contract, in which case the X signs could be many, and reciprocally joined so as to create a reticulum; it may also indicate that the writer wished to fill in a blank line in order to prevent non-authorzed additions (e.g. in P.Mich. inv. 239). However, Parsons himself recognized that in the case of a private letter between friends who esteemed and loved each other —and moreover were extremely generous with each other, I would add— this possibility is very remote and is probably to be ruled out.

Sometimes, a X sign was traced on the back of the letter, after rolling it up, with its writing inside; the X indicated the spot of the seal. But this reference also is to be excluded in our case, since, as Parsons rightly objected, "the usage should be too common for comment".24 Only later did he change his mind and, to compensate the lack of more plausible explanations, put forward the following hypothesis, based on the aforementioned meaning of the verb: "Ammonios may have wished to inform Apollonios that his letter was received in its sealed state. In other words, he wished to assure him that the letter had not been opened and read by someone else".25 Letters frequently transmitted secret information, intended for a restricted audience, as is stressed by Patricia A. Rosenmeyer.26

I find that it is much more resolutive to take the participle  as a reference to Christ and his Cross. Parsons, when he first published this letter, indeed suggested that

as a reference to Christ and his Cross. Parsons, when he first published this letter, indeed suggested that  might include a possible reference to the Christian cross, but this intuition, which was not supported by the realization that there is a nomen sacrum in this letter, was subsequently put aside by him.27 But it should have been developed. What is crucial is that the initial X of the opening greeting formula XAIPEIN has a superlinear stroke over it, according to the use of nomina sacra, which began precisely at that time. Hence, it indicates Christ. There are very few cases of letters on papyri in which the formula XAIPEIN is abbreviated as a X with a superlinear stroke, or better with a decoration on the right upper side of X, such as P.Mich. inv. 238, of the second century A.D. (

might include a possible reference to the Christian cross, but this intuition, which was not supported by the realization that there is a nomen sacrum in this letter, was subsequently put aside by him.27 But it should have been developed. What is crucial is that the initial X of the opening greeting formula XAIPEIN has a superlinear stroke over it, according to the use of nomina sacra, which began precisely at that time. Hence, it indicates Christ. There are very few cases of letters on papyri in which the formula XAIPEIN is abbreviated as a X with a superlinear stroke, or better with a decoration on the right upper side of X, such as P.Mich. inv. 238, of the second century A.D. ( ), and P.Tebt. 0568, of the second-third century A.D. (

), and P.Tebt. 0568, of the second-third century A.D. ( ), but in these cases the abbreviation is not a nomen sacrum, but simply indicates that X must be read as XAIPEIN.28 The case of Ammonius' letter is very different: here XAIPEIN is not abbreviated, which means that the very clear superlinear stroke over X must be the abbreviation of something else that is not written in extenso. The "letter marked with the X sign" that Ammonius received, probably from Apollonius, and which is probably identifiable with the reply to the

), but in these cases the abbreviation is not a nomen sacrum, but simply indicates that X must be read as XAIPEIN.28 The case of Ammonius' letter is very different: here XAIPEIN is not abbreviated, which means that the very clear superlinear stroke over X must be the abbreviation of something else that is not written in extenso. The "letter marked with the X sign" that Ammonius received, probably from Apollonius, and which is probably identifiable with the reply to the  in which Ammonius had written "funny things" to Apollonius, was therefore —like that which he is sending to Apollonius— a letter that was cryptically marked as Christian. Cryptically and symbolically. It is likely that in their correspondence Ammonius, Apollonius, and their "brothers" used this sacred sign, which was not easily recognizable by others, who could only see a tiny stroke, but was very significant to them.

in which Ammonius had written "funny things" to Apollonius, was therefore —like that which he is sending to Apollonius— a letter that was cryptically marked as Christian. Cryptically and symbolically. It is likely that in their correspondence Ammonius, Apollonius, and their "brothers" used this sacred sign, which was not easily recognizable by others, who could only see a tiny stroke, but was very significant to them.

In this new framework, many details of the letter become intelligible and the whole document, with an emphasis on the necessity of a cautious and circumspect behaviour and the use of a cryptic communication code, attests to the critical situation of the Christian communities in those days, when Christianity was a superstitio illicita and Christians had to try not to be denounced. Thus, I propose an analysis of the letter in this light: many aspects in its language, lexical choices, and rhetoric are telling. The new Christian reading of this letter allows us to recover one of the earliest Christian letters known and provides precious documentation of the birth of Christianity in Egypt, perhaps even in Alexandria itself, where Christianity in fact entered very early.

First of all, it is evident that Ammonius constantly addresses Apollonius with the appellative "brother".29  is used thrice, and once in the initial greeting formula, and

is used thrice, and once in the initial greeting formula, and  is employed once to indicate the community to which the addressee, Apollonius, belongs. This linguistic use, to be sure, is not exclusive of Christians, but is attested since the very beginning of Christianity, already in the New Testament, especially in the Acts of the Apostles and in the Letters of Paul and of James, then in Clement of Rome, in Polycarp's letter to the Philippians, in Barnaba's Letter and in the epistles of Ignatius. Sometimes, this can constitute a criterion to establish whether a Christian was addressing other Christians.30 This form of address transcending bodily kinship, however, is also found in both pagan and Jewish texts (see e.g. AI XIII 45), is typical of associations of the Greek East,31 and it is rather widespread precisely in the papyri, already in the Ptolemaic age: usually this term designated a colleague, or else kins belonging to the same generation.32 Llewelyn pointed out a parallel which, however, is not close from the chronological point of view:33

is employed once to indicate the community to which the addressee, Apollonius, belongs. This linguistic use, to be sure, is not exclusive of Christians, but is attested since the very beginning of Christianity, already in the New Testament, especially in the Acts of the Apostles and in the Letters of Paul and of James, then in Clement of Rome, in Polycarp's letter to the Philippians, in Barnaba's Letter and in the epistles of Ignatius. Sometimes, this can constitute a criterion to establish whether a Christian was addressing other Christians.30 This form of address transcending bodily kinship, however, is also found in both pagan and Jewish texts (see e.g. AI XIII 45), is typical of associations of the Greek East,31 and it is rather widespread precisely in the papyri, already in the Ptolemaic age: usually this term designated a colleague, or else kins belonging to the same generation.32 Llewelyn pointed out a parallel which, however, is not close from the chronological point of view:33  is found in documents belonging to the so-called archive of Theophanes (P. Herm. Rees 4 and 5), a member of a pagan circle, who adored Hermes Trismegistus.34 But it is possible to go back a long time: in the fourth century B.C., a decree from Entella35 established an "adoption into brotherhood" (

is found in documents belonging to the so-called archive of Theophanes (P. Herm. Rees 4 and 5), a member of a pagan circle, who adored Hermes Trismegistus.34 But it is possible to go back a long time: in the fourth century B.C., a decree from Entella35 established an "adoption into brotherhood" ( )36 which seems to be a unicum in the Greek world,37 since it was only in the Roman world that the adoptio in fratrem was widespread.38

)36 which seems to be a unicum in the Greek world,37 since it was only in the Roman world that the adoptio in fratrem was widespread.38

The presence of the  language is no evidence of Christianity per se, but it certainly becomes meaningful in connection with many other clues. The insistence on concord and reciprocal love that must obtain in Apollonius' community, likewise, is certainly no evidence of Christianity per se, but it is very interesting. In addition to

language is no evidence of Christianity per se, but it certainly becomes meaningful in connection with many other clues. The insistence on concord and reciprocal love that must obtain in Apollonius' community, likewise, is certainly no evidence of Christianity per se, but it is very interesting. In addition to  , Ammonius recommends that in Apollonius' community

, Ammonius recommends that in Apollonius' community  be always preserved. Of course, the fact that also in New-Testament letters a similar concern about the concord within the Christian community appears is not enough, per se, to make scholars conclude that Ammonius and Apollonius were Christians. But what is most interesting is the motivation that Ammonius adduces: Ammonius and his community should behave in this way in order to avoid malevolent voices and the consequences that these have already had on Ammonius's community.

be always preserved. Of course, the fact that also in New-Testament letters a similar concern about the concord within the Christian community appears is not enough, per se, to make scholars conclude that Ammonius and Apollonius were Christians. But what is most interesting is the motivation that Ammonius adduces: Ammonius and his community should behave in this way in order to avoid malevolent voices and the consequences that these have already had on Ammonius's community.

Around Apollonius's community, as results from this letter, there was a hostile climate, just like around that of Ammonius, and internal division within these communities would have called attention and attracted external hostility. Such was the situation of two Christian communities whose faith was officially considered to be a superstitio illicita —such as it had been probably since a senatus consultum under Tiberius.39 Morever, Christians were accused of flagitia, as is attested by Tacitus (Ann., XV, 44) for the time of Nero and for the second century by apologists such as Justin and Tertullian, and by pagan authors such as Apuleius.40 After that of Nero, toward the end of the first century there was that of Domitian; then there was peace for the Christians under Nerva, and immediately after this Trajan's rescript established that Christians conquirendi non sunt, but, if denounced by anyone, they had to be put to trial, and, if perseverantes, they had to be condemned to death. A more favourable interpretation of this rescript —whose ambiguity was denounced by Tertullian, who spoke of it as a sententia necessitate confusa— was offered by Hadrian.41 Now, those who denounced Christians, putting them at the risk of death, mostly were private citizens, enflamed by hostility: hence it is clear why Christian communities had to endeavour to attract no notice. It was vital for them not to offer anyone a chance of suspicion, hostility, and malevolence. This is why Ammonius is so worried and places such an emphasis on his recommendations, all the more so in that his community has already experienced external hostility: "Indeed, I pray that concord and reciprocal love remain among you, that you may not be an object of malevolent voices, and that what has happened to us may not happen to you as well. For my experience induces me to urge you to remain in peace without giving others any chance against you". Ammonius returns again to this dangerous situation of hostility at the end of his letter: "For my soul becomes serene whenever your name is present, and this although it is not accustomed to be tranquil, because of what is happening, but it endures". He is clearly referring here to a dangerous situation in which his community and that of Apollonius are involved, which is very well explained by the risks that Christian communities were running in the age of Domitian or of Trajan. Christians were continually at risk from denouncements. The same context of internal dissense and persecutory attacks from outside is found in a contemporary document, the letter of Clement of Rome to the Corinthians, who also employs the same couple of terms,  and

and  , which is used by Ammonius.

, which is used by Ammonius.

The use of  , which occurs twice in Ammonius's letter, is also interesting. This term is attested not only in literary texts, but also in inscriptions and papyri,42 one already in the first half of the second century A.D.,43 and is aso typical of the philosophical terminology, especially Stoic, between the end of the first and the beginning of the second century A.D., the period in which Ammonius wrote his letter and Epictetus lived. In Epictetus's works (Diss. I 30, 3-4; II 23, 5-19; III 1, 40; IV 5, 32) this term indicates the fundamental choice and intention that characterizes the whole ethical life of a person.44 In Ammonius's letter it denotes the intention that makes a gift or a thought welcome and appreciated, in that it indicates a friendly attitude and generosity. The connection between

, which occurs twice in Ammonius's letter, is also interesting. This term is attested not only in literary texts, but also in inscriptions and papyri,42 one already in the first half of the second century A.D.,43 and is aso typical of the philosophical terminology, especially Stoic, between the end of the first and the beginning of the second century A.D., the period in which Ammonius wrote his letter and Epictetus lived. In Epictetus's works (Diss. I 30, 3-4; II 23, 5-19; III 1, 40; IV 5, 32) this term indicates the fundamental choice and intention that characterizes the whole ethical life of a person.44 In Ammonius's letter it denotes the intention that makes a gift or a thought welcome and appreciated, in that it indicates a friendly attitude and generosity. The connection between  and

and  is especially clear in the syntagm

is especially clear in the syntagm  .

.

It is notable that Hellenistic moral philosophy, particularly Stoic, and its lexicon are especially typical of the so-called Pastoral Epistles in the New Testament,45 which are contemporary with Ammonius's letter, and which respond to the same concerns that are expressed by Ammonius. Christians felt the need to adhere to the moral conventions of the Greco-Roman world in order to avoid being judged badly and arousing suspicions and accusations; this is also why, notably, women are confined again to marriage, care for children and the house, and submission, whereas in Pauline communities they were respected leaders and apostles. This, of course, risked to enhance pagan hostility in a very dangerous period, and thus Christians such as the author(s) of the Pastorals preferred to sacrifice women and to contravene Jesus's and Paul's indications and praxis in order to be accepted by pagans, adhering to their moral standards. This sacrifice, however, was pretty much useless, as it did not prevent persecutions.

Ammonius's  toward Apollonius is also interesting, in that it belongs to the

toward Apollonius is also interesting, in that it belongs to the  terminology, which is a feature of this letter. Moreover, it offers a precise syntactical and lexical parallel with a Christian papyrus dating to the sixth century (P. Cairo Maspero III 6731), which mentions a

terminology, which is a feature of this letter. Moreover, it offers a precise syntactical and lexical parallel with a Christian papyrus dating to the sixth century (P. Cairo Maspero III 6731), which mentions a  46 This expression does not appear in other occurrences of the noun

46 This expression does not appear in other occurrences of the noun  in papyri.47

in papyri.47

As to the other term,  , in our letter, too, the exhortation to maintain peace is well present, along with that to feel reciprocal love, which is complementary. A compound with φιλ- occurs again twice to indicate the reciprocal relationships that unite Ammonius and Apollonius and also involve their community. At first, Apollonius is paradoxically reproached by Ammonius because he "oppresses" him with his continual demonstrations of kindness and generosity. To oppress through kindness is obviously an oxymoron, which also reveals Ammonius' rhetorical culture. These acts of kindness and generosity are indicated by Ammonius with the term

, in our letter, too, the exhortation to maintain peace is well present, along with that to feel reciprocal love, which is complementary. A compound with φιλ- occurs again twice to indicate the reciprocal relationships that unite Ammonius and Apollonius and also involve their community. At first, Apollonius is paradoxically reproached by Ammonius because he "oppresses" him with his continual demonstrations of kindness and generosity. To oppress through kindness is obviously an oxymoron, which also reveals Ammonius' rhetorical culture. These acts of kindness and generosity are indicated by Ammonius with the term  : "I do not want, o brother, you to oppress me with your continual acts of kindness, which I am unable to return". This sentence, which further excludes that the erciaTolfi Kexiaomévh may have been a contract, shows that Ammonius could not return Apollonius's acts of generosity, and this is what worries Ammonius, who clearly deemed recipricity necessary in a mutual relationship of

: "I do not want, o brother, you to oppress me with your continual acts of kindness, which I am unable to return". This sentence, which further excludes that the erciaTolfi Kexiaomévh may have been a contract, shows that Ammonius could not return Apollonius's acts of generosity, and this is what worries Ammonius, who clearly deemed recipricity necessary in a mutual relationship of  .

.

But the most important term of the rich48  lexicon49 used by Ammonius is

lexicon49 used by Ammonius is  , which indicates reciprocal affection and love. In this case, however, the relationship does not involve only Ammonius and Apollonius, but the whole community of the addressee: "I pray that concord and reciprocal love remain among you". A perfect parallel, already indicated by Parsons,50 is found in a Christian text, Nilus Ancyranus, PG 79, 144a:

, which indicates reciprocal affection and love. In this case, however, the relationship does not involve only Ammonius and Apollonius, but the whole community of the addressee: "I pray that concord and reciprocal love remain among you". A perfect parallel, already indicated by Parsons,50 is found in a Christian text, Nilus Ancyranus, PG 79, 144a:  51

51  . Stanton52 also devoted attention to the term

. Stanton52 also devoted attention to the term  , and I myself have searched both the literary Greek corpus and the corpus of inscriptions and papyri. From this investigation it emerged that

, and I myself have searched both the literary Greek corpus and the corpus of inscriptions and papyri. From this investigation it emerged that  is a unicum in the papyri, at least as far as we know at present. Precisely its relative rarity can also explain a possible mistake in our text,

is a unicum in the papyri, at least as far as we know at present. Precisely its relative rarity can also explain a possible mistake in our text,  , to be corrected into

, to be corrected into  . It seems to me remarkable that this noun, which is unattested elsewhere in papyri, in literary texts53 is attested only in Christian authors and in Hesychius. Furthermore, it is notable that in Nilus of Ancyra not only does this term appear, but the whole expression

. It seems to me remarkable that this noun, which is unattested elsewhere in papyri, in literary texts53 is attested only in Christian authors and in Hesychius. Furthermore, it is notable that in Nilus of Ancyra not only does this term appear, but the whole expression  exactly corresponds to that of Ammonius's letter.

exactly corresponds to that of Ammonius's letter.

Notwithstanding the doubts manifested by Parsons,54 it seems to me that there is indeed no valid reason to maintain that, if the palaeographic dating is between the first and the beginning of the second century, this dating must be erroneous, and in particular too early, if the letter is Christian. On the contrary, the parallels which I have highlighted with Clement of Rome and with some New-Testament letters and the probable historical context which I have advocated, between the time of Domitian and Trajan, seem to confirm the early paleographical dating and, at the same time, the fact that Ammonius and Apollonius were Christian. The latter conclusion is further corroborated by the use of a nomen sacrum to indicate Christ and by the reference to this symbolism contained in the Sibylline expression  . Indeed, this is probably one of the most ancient Christian epistolary documents outside the New Testament, perhaps the most ancient known together with Clement of Rome's letter to the Corinthians. It is a letter marked with Christ's nomen sacrum, and inserted in a correspondence between two men belonging to two communities, which seem to be Christian communities. The situation that emerges from the letter is characterized by internal division and external hostility, suspicions, and malevolence; Ammonius and Apollonius feel in danger. Ammonius even attests that serious consequences have already occurred in his community, and he hopes that at least the community of Apollonius will be spared. This is why he warmly recommends them internal unity and concord, in order to offer no occasion to their enemies. This was the situation of Christian communities between the end of the first and the beginning of the second century, in that Christianity was a superstitio illicita and its members could be denounced by anyone who happened to be hostile to them, especially because accusations of flagitia were widespread against them. This was the context of the persecution of Domitian and of Trajan's legislation regarding the Christians; even though Trajan did not allow anyone to seek Christians out, nevertheless, if they were denounced by anyone, they were put to trial, and, unless they apostatised, underwent capital punishment.

. Indeed, this is probably one of the most ancient Christian epistolary documents outside the New Testament, perhaps the most ancient known together with Clement of Rome's letter to the Corinthians. It is a letter marked with Christ's nomen sacrum, and inserted in a correspondence between two men belonging to two communities, which seem to be Christian communities. The situation that emerges from the letter is characterized by internal division and external hostility, suspicions, and malevolence; Ammonius and Apollonius feel in danger. Ammonius even attests that serious consequences have already occurred in his community, and he hopes that at least the community of Apollonius will be spared. This is why he warmly recommends them internal unity and concord, in order to offer no occasion to their enemies. This was the situation of Christian communities between the end of the first and the beginning of the second century, in that Christianity was a superstitio illicita and its members could be denounced by anyone who happened to be hostile to them, especially because accusations of flagitia were widespread against them. This was the context of the persecution of Domitian and of Trajan's legislation regarding the Christians; even though Trajan did not allow anyone to seek Christians out, nevertheless, if they were denounced by anyone, they were put to trial, and, unless they apostatised, underwent capital punishment.

This explains very well the Christians' need to use cryptic formulas, which could be confused by non-Christians with others frequently used in the pagan world (for instance, collegia sometimes hid churches).55 One of these ambiguous formulas was the X equipped with a superlinear stroke; a pagan would not have found it suspect, as it was simply the initial of  . But a Christian could read in it the abbreviation of the name of Christ, and would refer the expression

. But a Christian could read in it the abbreviation of the name of Christ, and would refer the expression  precisely to this cryptic sign, whereas this expression was altogether neutral for a pagan, who could think of a cancelled contract, a sealed letter, and so forth.

precisely to this cryptic sign, whereas this expression was altogether neutral for a pagan, who could think of a cancelled contract, a sealed letter, and so forth.

It was precisely in Egypt, and in the first decades of the second century —therefore, in the same place and time as Ammonius's letter was composed— that Papyrus Rylands 457 was written. It is kept at the J. Rylands Library in Manchester and contains passages from the Gospel of John (18, 31-33 and 37-38). After being published in 1935 it allowed scholars to fix the composition of the Gospel itself to some decades before A.D. 125 ca.56 In the time of Ammonius's letter, in Egypt, the Gospel of John was read and copied in Christian communities, among which there probably were those of Ammonius and Apollonius.

Probably they were in Alexandria, which was the main Christian center, where Christianity entered already in the first century. Their location there is suggested both by their culture and by their extreme caution. Of course danger was maximum in such a large center, in which moreover disorders and hostilities were frequent and the Jewish community was very big. They, or at least Ammonius, also travelled, as is indicated by the references to travel mantels, the key of the very little apartment, etc. It is in these same decades that the so-called Secret Gospel of Mark took shape. When Clement of Alexandria refers to it in the second half of the second century, he presents it as established in Alexandria for many decades. Clement recounts that this Gospel was written by Mark in Alexandria after writing the Gospel that is known to us as the Gospel of Mark:57 Mark, after publishing his first book, "composed a more spiritual Gospel", the so-called Secret Gospel of Mark, which needed to be read and interpreted. Indeed, the Gospel of Mark seems to have known different redactions.58

According to Eusebius, Mark was the first apostle of Egypt and founder of Christian communities in Alexandria itself: "They say that this man [Mark] was the first to be sent to Egypt to preach the gospel, which he had also written down, and that he was the first to establish churches in Alexandria itself" (Hist. Eccl. II 16, 1). Then Eusebius observes that the success of Mark's preaching around Alexandria may be inferred from the excellence of the Therapeutae described by Philo (De vita contemplativa 2 ff.), whom he mistakes for a Christian community. Eusebius also reports that in Nero's eighth year (A.D. 61/62) Annianus succeeded Mark in the ministry of the Alexandrian church (Hist. Eccl. II 24). The Acts of the Apostles associate with the earliest spread of Christianity in Alexandria Apollo, who then became a friend of Paul. According to the Western text of Acts 18:25, he first received a Christian instruction in Alexandria, where he lived. Then, Prisca and Aquila gave him a more precise instruction. Already at mid first century A.D. Christianity was preached and taught in Alexandria. This is also the background of Ammonius's letter, which was written some decades later.

Moreover, this Gospel of Mark, too, had a characterization of secrecy. According to Clement, it was reserved only to initiates because it could easily lead to misunderstandings,59 as in the case of the Carpocratians. This is Clement's account on the Secret Gospel of Mark in the writing found by Morton Smith60 in 1958 while he was cataloguing manuscripts in the library of the Greek Orthodox monastery of Mar Saba,61 near Jerusalem, in an eighteenth-century copy of a letter of Clement to a certain Theodore62 concerning the Gospel of Mark and the refutation of the Carpocratians' doctrines and found on the last leaves in the back of a collection of Ignatius of Antioch's epistles, published by Isaac Voss in 1646 (italics mine):

From the letters of the most holy Clement, the author of the Stromateis. (Letter) to Theodore.

You did well in reducing the unspeakable teachings of the Carpocratians to silence. For these are the "erring stars" referred to in the prophecy, who wander from the narrow road of the commandments into a boundless abyss of carnal and bodily sins. Indeed, priding themselves in knowledge, as they say, "of the profundities of Satan", they do not know that they are casting themselves away into "the lower world of the darkness" of falsity, and, boasting that they are free, they have become slaves of servile desires. Such people are to be opposed in all ways and completely, as, even in case they should say something true, one who loves the truth should not agree with them. For not all true things are the Truth, nor should that truth which merely seems true according to human opinions be preferred to the true Truth, that according to the faith.

Now of what they continue to maintain about the divinely inspired Gospel according to Mark, some are total falsifications, and others, even if they contain some true elements, nevertheless are not reported in an accurate way. For the true things being mixed with inventions, are falsified, so that, according to the saying, even the salt loses its savour. As for Mark, then, during Peter's stay in Rome he wrote an account of the Lord's deeds, not, however, declaring all of them, nor yet hinting at the secret ones, but selecting what he thought most useful for increasing the faith of those who were being instructed.63 But when Peter died as a martyr, Mark came over to Alexandria, bringing both his own notes and those of Peter, from which he transferred to his former book the things suitable to whatever makes for progress toward knowledge. Thus he composed a more spiritual Gospel for the use of those who were being perfected. Nevertheless, he did not yet divulge the information that was not to be revealed, nor did he write down the hierophantic teaching of the Lord, but to the stories already written he added others and, moreover, introduced certain sayings of which he knew the interpretation would, as a mystagogue, lead the hearers into the innermost sanctuary of that truth hidden by seven veils. Thus, in sum, he prepared matters, neither grudgingly nor incautiously, in my opinion, and, dying, he left his composition to the church in Alexandria, where it even yet is most carefully guarded, being read only to those who are being initiated into the great mysteries.64

But since the foul demons are always devising destruction for the race of men, Carpocrates, instructed by them and using deceitful arts, so enslaved a certain presbyter of the church in Alexandria that he got from him a copy of the secret Gospel, which he both interpreted according to his blasphemous and fleshly doctrine and, furthermore, polluted, mixing with the spotless and holy words utterly shameless lies. From this mixture is drawn off the teaching of the Carpocratians.

Therefore, as I said above, one should never yield to them; nor, when they put forward their falsifications, should one concede that the 'secret Gospel' is by Mark, but should even deny it on oath, as not all true things are to be said to all people. For this reason the Wisdom of God, through Solomon, advises, "Answer the fool from his folly", teaching that the light of the truth should be hidden from those who are mentally blind. Again it says, "From him who has not shall be taken away", and, "Let the fool walk in darkness". But we are "children of light", having been illuminated by "the dayspring" of the spirit of the Lord "from on high", and "Where the Spirit of the Lord is", it says, "there is liberty", for "All things are pure to the pure".

Thus, I shall not hesitate to answer the questions you asked, refuting the falsifications by the very words of the Gospel. For example, after "And they were in the road going up to Jerusalem", and what follows, until "After three days he will rise", the secret Gospel brings the following material word for word:65

And they come to Bethany. And a woman whose brother had died was there. And, coming, she prostrated herself before Jesus and says to him: Son of David, have mercy on me. But the disciples rebuked her. And Jesus, being angered, went off with her into the garden where the tomb was, and straightway a great cry was heard from the tomb. And going near Jesus rolled away the stone from the door of the tomb. And straightway, going in where the youth was, he stretched forth his hand and raised him, seizing his hand. But the youth, looking upon him, loved him and began to beseech him that he might be with him. And going out of the tomb they came into the house of the youth, who was rich. And after six days Jesus told him what to do and in the evening the youth comes to him, wearing a linen cloth over his naked body. And he remained with him that night, for Jesus taught him the mystery of the kingdom of God. And thence, arising, he returned to the other side of the Jordan.

After these words follows the text, "And James and John come to him", and all that section. But "naked man with naked man", and the other things about which you wrote, are not found therein.

And after the words, "And he comes into Jericho", the secret Gospel adds only: "And the sister of the youth whom Jesus loved and his mother and Salome were there, and Jesus did not receive them".66 But the many other things about which you wrote seem to be, and are, forgeries. Rather, the true explanation and that which is in agreement with the true philosophy...67

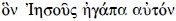

Clement, as is evident, used secrecy and cryptic language and allegorical interpretation to contrast, not possible pagan persecutors, as Ammonius did some decades earlier, but heretics, in particular the Carpocratians. Whether Mark is the author of this Gospel, which according to Clement stems from the late Sixties of the first century, or not —the latter is the thesis generally embraced by scholars—, there are some features in it that seem to me to point to a clearly Aramaic syntax. In particular, the expression  is no Greek at all, but it is Hebrew and Aramaic syntax. Such a turn of words is no more present either in Mark's canonical gospel or in John, where syntax appears more refined according to the koine. Moreover, the "disciple whom Jesus loved" is John in the gospel of John; however, in this gospel John reports that Jesus loved Martha, Mary, and Lazarus.

is no Greek at all, but it is Hebrew and Aramaic syntax. Such a turn of words is no more present either in Mark's canonical gospel or in John, where syntax appears more refined according to the koine. Moreover, the "disciple whom Jesus loved" is John in the gospel of John; however, in this gospel John reports that Jesus loved Martha, Mary, and Lazarus.

Moreover, the insistence on the motif of secrecy is not only in Clement, who was very sensitive to the notion of 'gnostic' teaching to be reserved only to those who were advanced in knowledge,68 such as the readers or hearers of the "Secret Mark" themselves, but also in the bit that he quotes from this gospel itself. Jesus is there portrayed as privately explaining the secrets of the kingdom of God to his disciples. The secrecy motif was vital for Mark and the community he led in Egypt, because they perceived themselves as persecuted by Jewish neighbors and Roman authorities and in constant danger. For them, too, the situation I have depicted above was a reality: they always risked to be denounced and put to a trial that would have led them either to apostasy or to death.

Clement himself, as results from Strom. 6.15.124.6-125.2; 6.15.126.2-3, 127.1, 129.4-130.1 (cf. 1.12.56.2), thought that Jesus taught the great mysteries of theology in parables so that the unworthy would not understand them, but explained these mysteries privately to his disciples, creating an oral tradition of the true exposition of Scripture.69 The notion of secrecy and cryptic communication was central to his thought.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aageson, J. W., Paul, the Pastoral Epistles, and the Early Church, Peabody, Hendrickson, 2008. [ Links ]

Achtemeier, P. J. Review of Smith, Clement, Journal of Biblical Literature, 93, 1974, pp. 625-628. [ Links ]

Amiotti, G., "Un singolare istituto di pace: Yadelphothetia di Nacone", in La pace nel mondo antico, a c. di M. Sordi, Milan, Vita e Pensiero, 1985, pp. 119-126. [ Links ]

Asheri, D., "Osservazioni storiche sul decreto di Nacone", Annali della Scuola Normale di Pisa, ser. III, 12, 1982, p. 707. [ Links ]

Bassler, J., 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus, Nashville, Abingdon, 1996. [ Links ]

Bauckham, R., "Salome the Sister of Jesus, Salome the Disciple of Jesus, and the Secret Gospel of Mark", Novum Testamentum, 33, 1991, pp. 245-275. [ Links ]

Beardslee, W. A., Review of Smith, Clement, Interpretation, 28, 1974, pp. 234-236. [ Links ]

Brown, R. E., "The Relation of 'The Secret Gospel of Mark' to the Fourth Gospel", Catholic Biblical Quarterly, 36, 1974, pp. 466-485. [ Links ]

Brown, S. G., Mark's Other Gospel: Rethinking Morton Smith's Controversial Discovery, Waterloo, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2007. [ Links ]

----------, "The Letter to Theodore: Stephen Carlson's Case against Clement's Authorship", JECS, 16, 4, 2008, pp. 535-572. [ Links ]

Bruce, F. F., The 'Secret' Gospel of Mark, London, Althone Press, 1974. [ Links ]

Chadwick, H., Alexandrian Christianity, London, S. C. M. Press, 1954. [ Links ]

Clark Kee, H., Review of Smith, Clement, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 43, 1975, pp. 326-329. [ Links ]

Collins, R. F., Letters that Paul Did Not Write, Wilmington, DE, Glazier, 1988. [ Links ]

----------, 1 & 11 Timothy and Titus: A Commentary, Louisville, Westminster John Knox, 2002. [ Links ]

Cosaert, C. P., The Text of the Gospels in Clement of Alexandria, Atlanta, SBL, 2008. [ Links ]

Criddle, A. H., "On the Mar Saba Letter Attributed to Clement of Alexandria", Journal of Early Christian Studies, 2, 3, 1995, pp. 215-220. [ Links ]

Crossan, J. D., Four Other Gospels: Shadows on the Contours of Canon, San Francisco, Harper & Row, 1985. [ Links ]

----------, The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant, San Francisco, Harper San Francisco, 1991. [ Links ]

Dorival, G., "Les débuts du christianisme á Alexandrie", in Alexandrie: une mégalopole cosmopolite, Paris, De Boccard, 1999, pp. 157-174. [ Links ]

Ehrman, B. D., "Response to Charles Hedrick's Stalemate", Journal of Early Christian Studies, 11:2, 2003, pp. 155-163. [ Links ]

Eyer, S., "The Strange Case of the Secret Gospel according to Mark. How Morton Smith's Discovery of a Lost Letter by Clement of Alexandria Scandalized Biblical Scholarship", Alexandria: The Journal for the Western Cosmological Traditions, 3, 1995, pp. 103-129. [ Links ]

Fiore, B., The Pastoral Epistles: First Timothy, Second Timothy, and Titus, Collegeville, Liturgical, 2007. [ Links ]

Fitzmyer, J., Reply to Morton Smith in "Mark's 'Secret Gospel?' ", America, 129, 1973, pp. 64-65. [ Links ]

----------, "How to Exploit a Secret Gospel", America, 128, 1973, pp. 570-572. [ Links ]

Foster, P., "Secret Mark: Its Discovery and the State of Research", The Expository Times, 117, 2, 2005, pp. 46-52. [ Links ]

Frend, W., "A New Jesus?", New York Review of Books, 20, 1973, pp. 34-35. [ Links ]

Fuller, R., Longer Mark: Forgery, Interpolation, or Old Tradition?, ed. W. Wuellner, Berkeley, Center for Hermeneutical Studies, 1975. [ Links ]

Funk, R. W.-R. W. Hoover-The Jesus Seminar, The Five Gospels: The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus, New York, Macmillan, 1993. [ Links ]

Giannantoni, G., La ricerca filosófica, I, Turin, Einaudi, 1978. [ Links ]

Grant, R. M., "Early Alexandrian Christianity", Church History, 40, 1971, pp. 133-144. [ Links ]

----------, "Morton Smith's Two Books", Anglican Theological Review, 56, 1974, pp. 58-65. [ Links ]

Griggs, C. W., Early Egyptian Christianity. From its Origin to 451C.E., Leiden, Brill, 1990. [ Links ]

Hägg, H. F., Clement of Alexandria and the Beginning of Christian Apophaticism, Oxford, OUP, 2006, pp. 135-140. [ Links ]

Hanson, R. P. C., Review of Smith, Clement, Journal of Theological Studies, 25, 1974, pp. 513-521. [ Links ]

Hardy, E. R., Christian Egypt, Church and People, New York, 1952. [ Links ]

Harland, P. A., "Familial Dimensions of Group Identity: "Brothers" (adelphoi) in Associations of the Greek East", Journal of Biblical Literature, 124, 2005, pp. 491-513. [ Links ]

Harris, W. V., Ancient Literacy, Cambridge, Mass., CUP, 1989. [ Links ]

Harrison, J., Paul's Language of Grace in Its Greco-Roman Context, Tübingen, Mohr, 2003. [ Links ]

Hedrick, C. W., "The Secret Gospel of Mark: Stalemate in the Academy", Journal of Early Christian Studies, 11.2, 2003, pp. 133-145. [ Links ]

Hemer, C. J., "Ammonius to Apollonius: Greeting", Buried History, 12, 1976, pp. 84-91. [ Links ]

Humphrey, H., From Q to Secret Mark: A Composition History of the Earliest Narrative Theology, London, T & T Clark International, 2006. [ Links ]

Hurtado, L. W., The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins, Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 2006. [ Links ]

Itter, A. C., Esoteric Teaching in the Stromateis of Clement of Alexandria, Leiden, Brill, 2009. [ Links ]

Jakab, A., Ecclesia Alexandrina, Bern, Lang, 2001, pp. 45-49. [ Links ]

Jay, J., "A New Look at the Epistolary Framework of the Secret Gospel of Mark", Journal of Early Christian Studies, 11:2, 2003, pp. 573-597. [ Links ]

Jeffery, P., The Secret Gospel of Mark Unveiled: Imagined Rituals of Sex, Death, and Madness in a Biblical Forgery, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2007. [ Links ]

Judge, E., Rank and Status in the World of the Caesars and St. Paul, Canterbury, University of Canterbury Press, 1982. [ Links ]

Klauck, H. J., Ancient Letters and the New Testament: A Guide to Context and Exegesis, Waco, Tx., Baylor University Press, 2006. [ Links ]

Koester, H., Review of Smith, Clement: American Historical Review, 80, 1975, pp. 620-622. [ Links ]

----------, Introduction to the New Testament, Berlin, De Gruyter, 1982. [ Links ]

----------, "History and Development of Mark's Gospel (From Mark to Secret Mark and 'Canonical' Mark)", in Colloquy on New Testament Studies, ed. Bruce Corley, Macon, GA, Mercer University Press, 1983, pp. 35-57. [ Links ]

Kolenkow, A. B., Response to Reginald Fuller, in Longer Mark: Forgery, Interpretation, or Old Tradition?, ed. W. Wuellner, Berkeley, Center for Hermeneutical Studies, 1975, pp. 33-34. [ Links ]

Kovacs, J., "Divine Pedagogy and the Gnostic Teacher according to Clement of Alexandria", JECS, 9, 2001, pp. 3-25. [ Links ]

Krause, D., 1 Timothy, London, T & T Clark, 2004. [ Links ]

Longer Mark: Forgery, Interpolation, or Old Tradition?, ed. R. Fuller, Berkeley, Center for Hermeneutical Studies, 1976. [ Links ]

Luijendijk, A. M., Greetings in the Lord: Early Christians and the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, Cambridge, Mass., CUP, 2008. [ Links ]

MacDonald, D., The Legend and the Apostle: The Battle for Paul in Story and Canon, Philadephia, Westminster, 1983. [ Links ]

Mann, C. S., Mark: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, New York, Doubleday, 1986. [ Links ]

Marshall, J. W., "I Left You in Crete", JBL, 127, 4, 2008, pp. 781-803. [ Links ]

Martin, A., "Aux origins de l'église copte: l'implantation et le development du Christianisme en Egypte", REA, 83, 1981, pp. 35-56. [ Links ]

Meeks, W. A., and J. T. Fitzgerald, The Writings of St. Paul, a Norton critical edition, New York-London, W. W. Norton & Company, 2007. [ Links ]

Mélèze Mondrzejewski, J., Les Juifs d'Egypte. De Ramsès II à Hadrien, Paris, PUF, 1991. [ Links ]

Merkel, H., "Auf den Spuren des Urmarkus? Ein neuer Fund und seine Beurteilung", Zeitschrift fuer Theologie und Kirche, 71, 1974, pp. 123-144. [ Links ]

Merz, A., Die fiktive Selbstauslegung des Paulus, Gottingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Fribourg: Academic Press, 2004. [ Links ]

Mimouni, S., "À la recherche de la communauté chrétienne d'Alexandrie aux premier-deuxième siècles", in Origeniana VIII, ed. L. Perrone, Louvain, Peeters, 2003, pp. 137-163. [ Links ]

Mitchell, M., "Patristic Counter-Evidence to the Claim that 'The Gospels Were Written for All Christians' ", New Testament Studies, 51, 2005, pp. 36-79. [ Links ]

Montevecchi, O., "THN EfflZTOAHN KEXIAXMENHN", Aegyptus, 80, 2000, pp. 189-192. [ Links ]

Nenci, G., "Sei decreti inediti da Entella", Annali della Scuola Normale di Pisa, ser. III, 10, 1980, pp. 1271-1275. [ Links ]

----------, "Considerazioni sui decreti di Entella", Annali della Scuola Normale di Pisa, ser. III, 12, 1982, pp. 1069 ff. [ Links ]

----------, "Nuove considerazioni sui decreti di Entella", Annali della Scuola Normale di Pisa, ser. III, 13, 1983, pp. 997-1001. [ Links ]

New Documents Illustrating Early Christianity, VI: A Review of the Greek Inscriptions and Papyri published in 1980-1981, by S. R. Llewelyn-R. A. Kearsley, Macquaire University, 1992. [ Links ]

Osborn, E., "Clement of Alexandria: A Review of Research, 1958-1982", The Second Century, 3, 1983, pp. 219-244. [ Links ]

Osiek, C.-M. Y. MacDonald, A woman's place: House churches in earliest Christianity, in coll. with J. H. Tulloch, Minneapolis, Fortress, 2006. [ Links ]

Paap, A. H. R. E., Nomina Sacra in the Greek Papyri of the First Five Centuries, Papyrologica Lugduno-Batava VIII, Leiden, Brill, 1959. [ Links ]

Pantuck, A. J.-S. G. Brown, "Morton Smith as M. Madiotes: Stephen Carlson's Attribution of Secret Mark to a Bald Swindler", Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus, 6, 2008, pp. 106-125. [ Links ]

Parker, P., "On Professor Morton Smith's Find at Mar Saba", Anglican Theological Review, 56, 1974, pp. 53-57. [ Links ]

Parsons, P. J., "The Earliest Christian Letter?", in Miscellanea Papyrologica (Pap. Flor. VII), Florence, 1980, p. 289. [ Links ]

Passoni dell'Acqua, A., Il testo del Nuovo Testamento, Turin, LDC, 1994. [ Links ]

Patterson, S. J., and H. Koester, "The Secret Gospel of Mark", in Robert J. Miller (ed.), The Complete Gospels: Scholars Version, Sonoma, Polebridge Press, 1992, pp. 402-405. [ Links ]

Pearson, B., "Earliest Christianity in Egypt: Some Observations", in The Roots of Egyptian Christianity, ed. B. A. Pearson-J. E. Goehring, Philadelphia, 1990, pp. 132-156. [ Links ]

----------, Gnosticism, Judaism, and Egyptian Christianity, Minneapolis, Fortress, 1990. [ Links ]

----------, "Earliest Christianity in Egypt: Further Observations", in The World of Early Egyptian Christianity, J. E. Goehring-J. Timbie (eds.), Washington, D. C., 2007, pp. 97-112. [ Links ]

Pericoli Ridolfini, F., "Le origini della Chiesa di Alessandria d'Egitto e la cronología dei vescovi alessandrini dei secoli i e II", RAL, ser. VIII, 17, 1962, pp. 308-343. [ Links ]

Petersen, N., Review of Smith, Southern Humanities Review, 8, 1974, pp. 525-531. [ Links ]

Piovanelli, P., "L'Evangile secret de Marc trente trois ans aprés, entre po-tentialités exégétiques et difficultés techniques", Revue Biblique, 114, 2007, pp. 52-72, 237-254. [ Links ]

Pohlenz, M., Die Stoa. Geschichte einer geistigen Bewegung, I, Gottingen, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1978. [ Links ]

Prophet, E. C., The Lost Years of Jesus: Documentary Evidence of Jesus' 17-Year Journey to the East, Livingston, MT, Summit University Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Quesnell, Q., "The Mar Saba Clementine: A Question of Evidence", Catholic Biblical Quarterly, 37, 1975, pp. 48-67. [ Links ]

----------, "A Reply to Morton Smith", Catholic Biblical Quarterly, 38, 1976, pp. 200-203. [ Links ]

Quinn, J., The Letter to Titus, New York, Doubleday, 1990. [ Links ]

Ramelli, I., "Fonti note e meno note sulle origini dei Vangeli: osservazioni per una valutazione dei dati della tradizione", Aevum, 81, 2007, pp. 171-185. [ Links ]

----------, "Alcune osservazioni sulle origini del Cristianesimo in Sicilia", Rivista di Storia della Chiesa in Italia, 53, 1999, pp. 1-15. [ Links ]

----------, "Una delle piu antiche lettere cristiane extra-canoniche?", Aegyptus, 80, 2000, pp. 169-188. [ Links ]

----------, "Elementi comuni della polemica antigiudaica e di quella anticristiana fra i e II sec. d.C.", Studi Romani, 49, 2001, pp. 245-274. [ Links ]

----------, "Nota per le fonti della persecuzione anticristiana di Nerone e le sue conseguenze, alla luce di due recenti apporti critici", Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, ser. II, Historia Antigua, 14, 2001, pp. 59-67. [ Links ]

----------, "Cristiani e vita politica: il cripto-Cristianesimo nelle classi dirigenti romane nel II secolo", Aevum, 77, 1, 2003, pp. 35-51. [ Links ]

----------, "Il senatoconsulto del 35 contro i Cristiani in un frammento porfiria no", prefaced by M. Sordi, Aevum, 78, 2004, pp. 59-67. [ Links ]

Ramelli, I., Corpus Hermeticum, Milan, Bompiani, 2005. [ Links ]

----------, "Mystérion negli Stromateis di Clemente Alessandrino: aspetti di continuita con la tradizione allegorica greca", in II volto del mistero. Mistero e religione nella cultura religiosa tardoantica, ed. A. M. Mazzanti, Castel Bolognese, Itaca Libri, 2006, pp. 83-120. [ Links ]

----------, "Nuove osservazioni per lo studio del rescritto di Adriano sui Cristiani", Aevum, 81, 2008, pp. 137-148. [ Links ]

----------, "Apuleius and Christianity: the Philosopher-Novelist in Front of a New Religion", forthcoming in the Proceedings of the ICAN 2008, International Conference on the Ancient Novel, Lisbon University, 21st-26th July 2008. [ Links ]

Reale, G., Storia della filosofia antica, IV, Milan, Vita e Pensiero, 1993. [ Links ]

----------, Storia della filosofia greca e romana, VI, Milan, Bompiani, 2004. [ Links ]

Reese, J., Review of Smith, Clement, Catholic Biblical Quarterly, 36, 1974, pp. 434-435. [ Links ]

Richards, W. A., Difference and Distance in Post-Pauline Christianity, New York, Lang, 2002. [ Links ]

Richardson, C. C., "Review of Smith, Clement", Theological Studies, 35, 1974, pp. 571-577. [ Links ]

Rinaldi, G., Cristianesimi nell'Antichita, Chieti-Roma, GBU, 2008. [ Links ]

Roberts, C. H., Nomina Sacra, London, OUP, 1979. [ Links ]

Rosenmeyer, P. A., Ancient Epistolary Fiction, Cambridge, CUP, 2001. [ Links ]

Schenke, H.-M., "The Mystery of the Gospel of Mark", The Second Century, 4, 1984, pp. 65-82. [ Links ]

Schmidt, D. D., The Gospel of Mark. Scholars Version, Sonoma, Polebridge Press, 1990. [ Links ]

Schüssler Fiorenza, E., In Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins, New York, Crossroads, 1992. [ Links ]

Scroggs, R., and Kent I. Groff, "Baptism in Mark: Dying and Rising with Christ", Journal of Biblical Literature, 92, 1973, pp. 531-548. [ Links ]

Sorabji, R., Emotion and Peace of Mind: From Stoic Agitation to Christian Temptation, Oxford, OUP, 2000. [ Links ]

Smith, M., Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1973. [ Links ]

----------, Reply to Joseph Fitzmyer in "Mark's 'Secret Gospel?"', America, 129, 1973, pp. 64-65. [ Links ]

----------, "Merkel on the Longer Text of Mark", Zeitschrift fuer Theologie und Kirche, 72, 1975, pp. 133-150. [ Links ]

----------, "On the Authenticity of the Mar Saba Letter of Clement", Catholic Biblical Quarterly, 38, 1976, pp. 196-199. [ Links ]

----------, "A Rare Sense of prokoptó and the Authenticity of the Letter of Clement of Alexandria", in God's Christ and His People: Studies in Honor of Nils Alstrup Dahl, Jacob Jervell and Wayne A. Meeks (ed.), Oslo, Universitetsforlaget, 1977. [ Links ]

----------, Jesus the Magician, New York, Harper & Row, 1978. [ Links ]

----------, "Clement of Alexandria and Secret Mark: The Score at the End of the First Decade", Harvard Theological Review, 75, 1982, pp. 449-461. [ Links ]

Stagg, F., "Review of Smith's Clement", Review and Expositor, 71, 1974, pp. 108-110. [ Links ]

Stanton, G. R., "The Proposed Earliest Christian Letter on Papyrus and the Origin of the Term Philallelia", Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 54, 1984, pp. 49-63. [ Links ]

Stepp, P. L., Leadership Succession in the World of the Pauline Circle, Sheffield, Sheffield Phoenix, 2005. [ Links ]

Stroumsa, G., "Comments on Charles Hedrick's Article: A Testimony", Journal of Early Christian Studies, 11:2, 2003, pp. 147-153. [ Links ]

Thiede, C. P., Jesus. Der Glaube. Die Fakte, Augsburg, Sankt Ulrich Verlag, 2003. [ Links ]

Trevijano, E., "The Early Christian Church in Alexandria", StudPatr, 12B, 1975, pp. 471-477. [ Links ]

Van der Horst, P. W., "Het 'geheime Markusevangelie'. Over een nieu-we vondst", Nederlands Theologisch Tijdschrift, 33, 1979, pp. 27-51, reprinted in Idem, De onbekende god, Utrecht, s. e., 1988, pp. 37-64. [ Links ]

Van Neste, R., Cohesion and Structure in the Pastoral Epistles, London, T & T Clark, 2004. [ Links ]

Von Campenhaijsen, H., "Polykarp von Smyrna und die Pastoralbriefe", in Aus der Frühzeit des Christentum, Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck, 1964, pp. 10-252. [ Links ]

Wilson, S. G., Luke and the Pastoral Epistles, London, SPCK, 1979. [ Links ]

Yamauchi, E. M., "A Secret Gospel of Jesus as 'Magus?' A Review of Recent Works of Morton Smith", Christian Scholars Review, 4, 1975, pp. 238-251. [ Links ]

1 This article is a revised and much expanded version of the paper I delivered at the FIEC Congress Berlin 24-29 August 2009, Recent Discoveries panel. I am very grateful to all friends and colleagues who commented on it before, during, and after the congress.

2 A good survey of Christian letters in the Oxyrhynchus papyri is now offered by Luijendijk, Greetings.

3 Letter writing was part of everyday life in Hellenistic Egypt. See Harris, Ancient Literacy, pp. 127-128.

4 See the argument adduced in the diptych Ramelli, Una delle piu antiche lettere, pp. 169-188, and Montevecchi, ΤΗΝ ΕΠΙΣΤΟΛHΝ KΕΧΙΑΣMΕΝHΝ, pp. 189-192.

5 Nomina sacra in early Christianity are studied by Paap, Nomina Sacra; Roberts, Nomina Sacra, and Hurtado, The Earliest Christian Artifacts, pp. 95-134. The abbreviation for  is usually a superlinear stroke over XC, XP, or XPC, attested in papyri of the New Testament: P1 (P. Oxy. 2), A.D. 250; P4 (Suppl. Gr. 1120), A.D. 67 to 175; P9 (P. Oxy. 402), A.D. 200-300; P15 (P Oxy. 1008), A.D. 250-300; P16 (P Oxy. 1009), of the same period; P18 (P Oxy. 1079), of the same period; P38 (P Mich. Inv. 1571), A.D. 175 to 225; P40 (P Heidelberg G. 645), A.D. 200-300; P45 (P. Chester Beatty I), A.D. 200; P46 (P. Chester Beatty II + P. Mich. Inv. 6238); P47 (P Chester Beatty III), A.D. 250-300; P49 (P. Yale 415 + 531), A.D. 250; P65 (PSI XIV 1373), A.D. 250; P72 (P Bodmer VII and VIII), A.D. 250-300; P78 (P. Oxy 2684), of the same period; P91 (P. Mil. Vogl. Inv. 1224 + P. Macquarie Inv. 360), A.D. 250; P92 (P. Narmuthis 69.39a + 69.229a), A.D. 250-275; P106 (P Oxy. 4445), A.D. 200-250.

is usually a superlinear stroke over XC, XP, or XPC, attested in papyri of the New Testament: P1 (P. Oxy. 2), A.D. 250; P4 (Suppl. Gr. 1120), A.D. 67 to 175; P9 (P. Oxy. 402), A.D. 200-300; P15 (P Oxy. 1008), A.D. 250-300; P16 (P Oxy. 1009), of the same period; P18 (P Oxy. 1079), of the same period; P38 (P Mich. Inv. 1571), A.D. 175 to 225; P40 (P Heidelberg G. 645), A.D. 200-300; P45 (P. Chester Beatty I), A.D. 200; P46 (P. Chester Beatty II + P. Mich. Inv. 6238); P47 (P Chester Beatty III), A.D. 250-300; P49 (P. Yale 415 + 531), A.D. 250; P65 (PSI XIV 1373), A.D. 250; P72 (P Bodmer VII and VIII), A.D. 250-300; P78 (P. Oxy 2684), of the same period; P91 (P. Mil. Vogl. Inv. 1224 + P. Macquarie Inv. 360), A.D. 250; P92 (P. Narmuthis 69.39a + 69.229a), A.D. 250-275; P106 (P Oxy. 4445), A.D. 200-250.

6 See Thiede, Jesus, p. 113.

7 New Documents by Llewelyn and Kearsley, pp. 169-177.

8 In the aforementioned study in Aegyptus.

9 The translation of  is hotly debated in that expression is a unicum; both Parsons and Llewelyn prudentially translate "crossed", in a rather generic way, just like James Harrison (Paul's Language, pp. 82-83). See below, where I fully explain the reason why I translate "marked with X", meaning with the Greek letter X.

is hotly debated in that expression is a unicum; both Parsons and Llewelyn prudentially translate "crossed", in a rather generic way, just like James Harrison (Paul's Language, pp. 82-83). See below, where I fully explain the reason why I translate "marked with X", meaning with the Greek letter X.

11 Or "you will receive", a medial future from  .

.

12 My translation follows the punctuation suggested by Bülow Jacobsen (cf. BL VIII 265 with a reference to P. Oxy. XLIX 3505, note to the lines 24-25), which also implies that Leonas is the scribe and a slave. Parsons and Llewlyn, on the other side, both read  , "... because of what is happening. But Leonas endures with perseverance. I greet you, o lord, you and all of your household".

, "... because of what is happening. But Leonas endures with perseverance. I greet you, o lord, you and all of your household".

13 Parsons, "The Earliest Christian Letter?", p. 289.

14 One was addressed by Constantine to Chrestus, bishop of Syracuse, and another by the same to Elaphius, vicar of Africa, both stemming from A.D. 313-314.

15 Stanton, The Proposed Earliest Christian Letter, pp. 49-63.

16 Judge, Rank and Status, pp. 20-23.

17 Hemer, Ammonius to Apollonius, pp. 84-91.

18 New Documents... VI, p. 177.

19 Klauck, Ancient Letters, provides a precious survey on ancient letter writing and especially the early Christian epistolary literature in its ancient literary and socio-cultural context.

20 Ramelli, Una delle più antiche lettere cristiane, and Montevecchi, Tèn Epistolèn Kekhiasménen.

21 Nota per le fonti, pp. 59-67.

22 If one considers literary attestations, both the perfect participle  and the noun

and the noun  or

or  are almost exclusively attested in pagan authors. The only Christian who uses

are almost exclusively attested in pagan authors. The only Christian who uses  in the first centuries A.D. is Justin Apol. 60, 5, according to whom Plato mistook for a simple xiaa|ma one of the pre-figurations of the cross of Christ. As for the participle, it is only attested in pagan authors, in technical senses, e.g. in Nicomachus, Theologoumena arithmeticae, p. 24, 7 in a geometrical-astrological context (= Iamblichus, Theologoumena arithmeticae, p. 24, 7); Hippiatrica Berolinensia, 26, 4 and 117, 1, in a medical sense; likewise Ps. Galen, De fasciis, vol. 18a, p. 803, 9 Kuhn.

in the first centuries A.D. is Justin Apol. 60, 5, according to whom Plato mistook for a simple xiaa|ma one of the pre-figurations of the cross of Christ. As for the participle, it is only attested in pagan authors, in technical senses, e.g. in Nicomachus, Theologoumena arithmeticae, p. 24, 7 in a geometrical-astrological context (= Iamblichus, Theologoumena arithmeticae, p. 24, 7); Hippiatrica Berolinensia, 26, 4 and 117, 1, in a medical sense; likewise Ps. Galen, De fasciis, vol. 18a, p. 803, 9 Kuhn.

23 POxy XLII, pp. 144-146.

24 Parsons, POxy XLII, p. 145.

25 Parsons, New Documents, p. 173.

26 Ancient Epistolary Fiction, p. 27.

27 Parsons, POxy XLII, pp. 144-146; Id., The Earliest Christian Letter, p. 289; Llewelyn does not express any opinion on this point: New Documents ... VI, p. 172.

28 In P.Tebt. 0470 (A.D. 112) what might appear as a superlinear stroke on XAIREIN is not such, but a sign in the papyrus, which is badly preserved and is destroyed exactly on the left of XAIREIN.

29 Indeed, it was immediately noticed by Parsons in his edition, London, 1974, 144-146, who put this in relationship with Christianity.

30 See my Alcune osservazioni sulle origini del Cristianesimo in Sicilia, "Rivista di Storia della Chiesa in Italia", 53 (1999), 1-15.

31 PHarland, Familial Dimensions, pp. 491-513.

32 Cf. Stanton, The Proposed, pp. 49-63; Judge, Rank and Status, pp. 20-23. Likewise Tibiletti, Le lettere private, pp. 31-32.

33 Llewelyn, New Documents, pp. 175.

34 For Hermeticism in Egypt see Ramelli, Corpus Hermeticum, Integrative Essay.

35 Amiotti, Un singolare istituto, pp. 119-126.

36 See Nenci, Sei decreti inediti, 1271-1275; Id., Considerazioni, pp. 1069 ff.; Id., Nuove considerazioni, pp. 997-1001.

37 Cf. Asheri, Osservazioni, p. 707.

38 Cf. Amiotti, Un singolare istituto, p. 123. See Tac., Ann., XI 25: "primi Aedui senatorum in urbe ius adepti sunt. Datum id foederi antiquo, et quia soli Gallorum fraternitatis nomen cum populo Romano usurpant".

39 See my Il senatoconsulto del 35, pp. 59-67.

40 See my Elementi comuni, pp. 245-274; Ead., Cristiani e vita politica, pp. 3551; Apuleius and Christianity.

41 See my Nuove osservazioniper lo studio del rescritto di Adriano, pp. 137-148.

42 Of course, this term is also widely sttested in literary sources, fon instance in the rhetorical, historical, and medical fields. See Llewelyn, New Documents, p. 174, n. 189.

43 P Giss. 68, 10. For this papyrus and the presence of  in papyrus letters see Tibiletti, Le lettere private, pp. 37, 42-43, 83, 104, 110.

in papyrus letters see Tibiletti, Le lettere private, pp. 37, 42-43, 83, 104, 110.

44 Pohlenz, Die Stoa, I, pp. 332 ff.; Reale, Storia, IV, pp. 115 f.; Id., Storia della filosofia greca e romana, VI, pp. 344-352; cf. Giannantoni, La ricerca filosófica, I, p. 275. See also SVF, III 173; Sorabji, Emotion, pp. 301 ff. and passim.