Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Nova tellus

Print version ISSN 0185-3058

Nova tellus vol.27 n.1 Ciudad de México Jun. 2009

Artículos

The First Sicilian School of Translators*

Daniele Molinini

Université Paris 7. dmolinini@yahoo.it.

Recepción: 21 de enero de 2009.

Aceptación: 11 de mayo de 2009.

Resumen

La Sicilia normanda de los reyes Ruggero II (1095-1154) y Guglielmo I (1125-1166) representa un puente esencial para la transmisión de la herencia clásica y del conocimiento árabe. En este artículo queremos concentrarnos en este movimiento de transmisión, subrayar las diferencias con respecto de la situación en España y mostrar quiénes fueron sus actores principales y en qué consiste la originalidad de la Primera Escuela Siciliana de Traductores.

Palabras clave: escuela siciliana, conocimiento árabe, tradición clásica, traducción.

Abstract

Norman Sicily of King Roger II (1095-1154) and William I (1125-1166) represents an essential bridge for the transmission of classical heritage and Arab knowledge. In this paper we want to focus on this movement of transmission, stress the differences towards the Spanish case and show who the main actors were and in what consists the originality of the First Sicilian School of Translators.

Keywords: arab knowledge, classical tradition, sicilian school, translation.

Introduction

The important role played by Italy, Spain and the Eastern Empire in the transmission of ancient philosophical and scientific knowledge in the period between the eleventh and the fifteenth century is well-known today.1 In particular, if we focus on the "bridge" of Southern Italy, we can see in the Norman Sicily of King Roger II (1095-1154) a real crossroads area between the Arab, the Greek and the Latin worlds. The Byzantine domination, the Arab one and the following Norman dominion, started in 1091 with the conquest of Noto, made of Norman Sicily a common ground for the Greek, Arab, Jewish and Latin cultures. This fact emerges clearly under Roger II and should be seen as the foundation for the future kingdom of Frederick II.

The stability of Roger II's reign and the tolerance of Roger himself allowed Muslim and Greek people to keep their own language and preserve ancient elements not only as far as their customs were concerned, but also in their chancelleries and administrations. The king had been educated by Greek preceptors in Palermo and his court was a mixture of Greek, Arab and Latin elements. Roger II's royal curia preserved many Arabic and Byzantine components in administration and was ruled by influential figures such as the Christian emir of Syria George of Antioch and the Byzantine theologian Nilus Doxopatres. The output of such a cosmopolitan atmosphere, with the advantage for scholars of having direct contact with both Greek and Arab world, is the production of some original scientific works such as the Book of Roger of the geographer Al-Idrisi, an important description of the world commissioned by the king himself and completed one month before the death of Roger (1154).2 The production of translations was also inevitable, and it was directly encouraged by the Sicilian kings, from Roger to Frederick II.

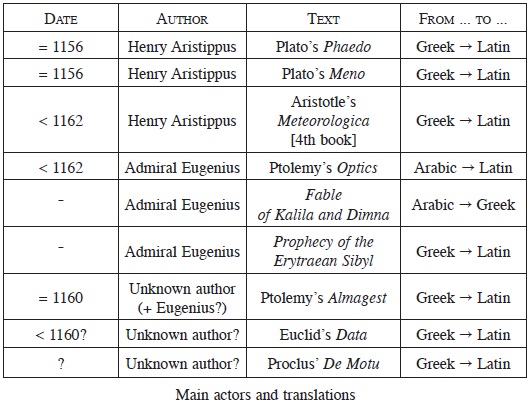

Roger's kingdom must be considered as the starting point for some important translations completed under William I (1125-1166). Those works were originally written in Greek or in Arabic such as, among others, Ptolemy's Optics, Ptolemy's Almagest, Plato's Meno and Phaedo. In this paper we want to stress the importance of the intellectual activity of the "First Sicilian School of Translators", provide a summary account of the main actors and offer a synthesis of the cultural enterprise which comes from the two different periods in which the activity of the School can be divided. In order to analyse the School, a very brief comparison with the Spanish movement of translations is necessary and helpful.

The first period of the School: output of original works

The activity of the First Sicilian School of Translators could be divided in two periods: a period under Roger II, from about 1140 to 1154, characterized by the production of some original works, and a second period of translations under the following kingdom of his son William I, from 1154 to about 1166.

The cultural activity developed in Roger's Sicily is directly linked to four main features of the first Norman Sicily: 1) it was a 3-language society (we have evidence of this from 3-language royal diplomas, symbols of the royal power, coins, three-language epigraphs and inscriptions),3 2) it preserved Arab and Greek elements and was influenced by them (architectural elements, urbanistic elements and buildings, customs, administration, way of life, Roger's Latin curia was a mixture of them),4 3) it was the heart of a real crossroads area (Sicily was the "coeur" of the Mediterranean Area and had direct commercial, diplomatic but also informal contacts with the Arab, the Byzantine and the Latin world)5 and, in line with a vision of Byzantine power, 4) the king himself was interested in science and culture and encouraged the cultural life of his court (geometers, astronomers, poets, grammarians, lived in Palermo and had contacts with the King).6 In this atmosphere of exchange we see the output of some original works such as Nilus Doxopatres' History of the five patriarchates (1143), in Greek, and the Book of Roger (1154) of the geographer Al-Idrisi, in Arabic. Poems in Greek were composed by a circle of men very close to Roger's ammiratus ammiratorum George of Antioch.7 All those works were written in the mother-tongue of the authors and the cultural movement was very close to Roger's curia. While an important group of codices of the New Testament seems to be linked to a group of copysts of Roger's court,8 interest in the Palermitan court for the Greek literature is attested by the presence of works such as the novel Aethiopica by Heliodorus and by the discourses of the monk Filagato Ceramide, who was also interested in Greek medicine and in particular in the works of Galen.

The second period: translations

A new period of the School starts with the death of Roger II (1154) and continues through William I's reign. Here we see the output of important scientific and philosophical translations from Greek and Arabic into Latin. This second period can not be separated from the previous phase but must be seen as the natural continuity of a process which had already begun under Roger II. The translators had grown up in Roger II's Latin curia and had the opportunity to pick up and absorb both the Arab and the Greek intellectual heritage. The main actors are Henry Aristippus (died in 1162), archdeacon of Catania, the admiral Eugenius (1130-1202), son of the admiral Giovanni, and an unknown scholar from Salerno.

The importance of those actors is evident from their translations. Henry Aristippus translated the fourth book of Aristotle's Meteorologica from the Greek into Latin before 1160 and his translations of Plato's Meno and Phaedo, made in 1156 from Greek manuscripts, are considered today the first known translations of those dialogues into Latin before the new translations of the XVth century. From the Preface to the translation of the Phaedo, in his dedication to a certain Roboratus fortune who was about to return to England, Aristippus gives us evidence of the presence in Norman Sicily of important scientific and philosophical texts such as the Mechanics of Hero, the Optics of Euclid, the Posterior Analytics of Aristotle: "In Siciliy you have the library of Syracuse [...] you have access to the Mechanics of Hero, the Optics of Euclid, the Posterior Analytics of Aristotle and other philosophical works".9

Admiral Eugenius, whose mother tongue was Greek, translated The fable of Kalila and Dimna from Arabic to Greek and the Prophecy of the Erythraean Sibyl from Greek to Latin.10 But his greatest known contribution to the transmission of scientific knowledge is the translation of Ptolemy's Optics from Arabic to Latin. Ptolemy's Optics translation done by Admiral Eugenius is of primary importance because the Arabic and the Greek versions have been lost and we know this text only through Eugenius' translation. The importance of the translation is also due to the way in which it and the commentary were made. In the Preface Eugenius illustrates the difficulty and the method of his translation, which was done de verbo ad verbum:

Verumptamen, quia universa linguarum genera proprium habent ydioma, et alterius in alterum translatio, fideli maxime interpreti, non est facilis, et presertim arabicam in grecam aut latinam transferre volenti tanto difficilius est quanto maior diversitas inter illas, tam in verbis et nominibus quam in litterali compositione, reperitur.11

He remarks that he had before him two manuscripts in Arabic, of which he used the more recent as being the more accurate: "Ex duobus exemplaribus quorum novissimum, unde presens translatio facta fuit, veracius est".12

As observed by Albert Lejeune, who edited the Optics in 1956,13 the Arabic version used by Eugenius for his translation was probably made on a Greek original.

An unknown student from Salerno is the author of a translation in to Latin of Ptolemy's Almagest from a Greek manuscript. This translation, which was terminated between 1158 and 1160, preceds by about fifteen years Gerard's translation from the Arabic (1175) and largely anticipates Trapezuntius' translation from the Greek (1451).

The Greek manuscript had been brought from Constantinople to Palermo in 1158 by Henry Aristippus, who had received it as a present from the Emperor Manuel I Comnenus during his embassy in the Eastern Empire (1158-1160). The Salernitan scholar came to Sicily in order to study the manuscript but the text was too difficult for him. He observes that, before attacking the translation of the Almagest, he studied the following works: Data, Optica and Catoprica of Euclid and the Physica Elementa Sive De Motu of Proclus.14 From a passage in the translation it seems that the unknown translator from Salerno had also seen a copy of Aristotle's De Caelo.15 He was probably helped by admiral Eugenius in the translation of the Almagest. In the Prologue he shows his gratitude and his admiration for the admiral, pointing out that Eugenius was not only skilled in Arabic and Greek, but also in Latin: "Eugenium, virum tam grece quam arabice lingue peritissimus, latine quoque non ignarus".16

Conclusions and analysis

We can say that Roger II's court, far from being an isolated centre of culture, could profit from having direct and unbroken contacts with the Arab and the Byzantine worlds and of being a fully three-language society thanks to its scholars, of different mother-tongues, who were fluent in three languages. As remarked by Roshdi Rashed, if in Spain and in the Eastern Empire the translations are generally associated with one departure language (Arabic for Spain and Greek for the Eastern Empire), Sicily was a truly original and unique case and had the great advantage of being "liée aux deux [langues] à la fois".17 This particular situation made possible access to manuscripts and cultural heritage via a "double route";18 moreover, it permitted the output of some original works in the mother tongue of the authors (Greek, Arabic, Latin) and opened the road to the translations made under William I.

While the same period in Spain is well-studied, and for Italy we have a great quantity of studies about the later cultural movement under Frederick II, cultural activity under Roger II and his son William has not received the necessary attention yet. The corpus of Southern Italy's libraries of this period has not been well established, and it is in need of further study in order to get a better "perspective of continuity" of the transmission and production of scientific knowledge in the Mediterranean area. As suggested by Haskins, the corpus of the libraries of the Sicilian kings might well have formed the primitive nucleus of the Greek collections of the Vatican.19 The Prologue of Aristippus to his translation of the Phaedo, Al-Idrisi's Book of Roger or the remarks made by the unknown Salernitan scholar in his translation of the Almagest, give us an important evidence of the presence and the circulation in twelfth-century Sicily of major scientific and philosophical texts such as Euclid's Data, Optica and Catoprica, Proclus' Physica Elementa sive de Motu, Aristotle's Meteorologica, De Caelo and Posterior Analytics, Hero's Mechanica and various Arabic geographical texts such as Al-Khwârizmi's Kitab surat al-ard.20 This is a very important point in order to reconstruct not only the transmission of knowledge during the twelfth century, but also the later circulation of ancient knowledge in Italy until the new translations of the fifteenth century.

What are the features, what is the importance of the First Sicilian School of Translators? Why is the contribution of those translators so important for the history of the transmission of knowledge and for the history of science? Why do we call them a school?

We could sum up the importance of the movement in a few telling points. A very brief comparison with the movement of the same period in Toledo will help to clarify the distinctiveness of the Sicilian case and the differences with respect to the Toledo School.

The Sicilian scholars had the opportunity to have access not only to Arabic manuscripts but also directly to Greek texts via languages which were still spoken in the South of Italy. The fact that there were languages "still living" is evident from the work of Eugenius or Nilus Doxopatres, whose native tongue was Greek, and must be understood as a consequence of the tolerance and the cultural exchange which characterized Roger II's cosmopolitan Sicily. This situation, differently from Spain, facilitated the translations and permitted the agents not to turn to intermediate translations in the vernacular (as was generally the case in Toledo). Another aspect which distinguishes Sicily from Spain concerns the "driving force" behind the translations. If the movement of translation in Spain was influenced by what Burnett defined as "The context of the Cathedral",21 the translation enterprise of the First Sicilian School was not an "export-market" and was not influenced by the Church. The natural places of the translations are the Norman Court and the Arab, Greek, Jewish communities still alive in the south of Italy, communities which had formal and informal contacts between them. The role of those social groups is very important, expecially because they had also contacts with the Eastern Empire and the Arab world.

If we ask ourselves what the real driving force behind the cultural movement born in Sicily was, we may offer an hypothesis. As far as we know, in Sicily there was no demand by intellectual centers (such as universities, monasteries) and the translations had no utilitarian aims. From our analysis22 the driving force behind the movement of translations must be traced back to three main elements: the vision of Byzantine power, which characterized the first Norman kingdom in Southern Italy and encouraged the output of works in different languages; an easy access to sources, which depends on the rich historical background of Sicily and on the central position of Sicily in the mare magnum; the sensation of a "language loss", which begins under William I and gives rise to the translations.23 Also, even if the number of translations made in Spain is greater than the number of translations made in Sicily, and the quality of the Sicilian translations is often not so good,24 the originality and the social dimension which characterized xn th century Sicily whould offer a new sense of continuity which helps us to "read" and understand the intellectual movement under Frederick II and the second generation of translators. In Sicily we have the first known Latin translation of the Almagest and the only known translation of Ptolemy's Optics. The actors formed a "School": they were linked together and aware of each other's work, as emerges from the preface of Aristippus, from the remarks of Eugenius and from the paragraph of the unknown scholar from Salerno which links the main actors. The remarks made by Eugenius about his method of translation and the importance of the Optics are a clear sign of a consciousness of the translator, of his will to produce a rigorous work. We can say that the work of those scholars was not that of an élite which read and translated ancient texts just for fun. It was a serious and professional enterprise.

Comparative studies, studies on the relationships between the translators and the court and new studies in order to define the corpus of the Sicilian libraries are required so as to obtain a better analysis of xn th century Sicily. In addition to this, the role of Mozarabs and Jewish Communities in the process of the transmission of knowledge in twelfth-century Sicily has not been established. A better comprehension of Roger's and William's Sicily, and in particular a deep study of Arabic, Greek and Jewish sources, might also account for the important role of translations and original works of the later "entourage" of Frederick II, such as Scott's, Fibonacci's or John's.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abattouy, M., J. Renn & P. Weinig, "Transmission as Transformation: The Translation Movements in the Medieval East and West in a Comparative Perspective", Science in Context, 14, 2001, pp. 1-12. [ Links ]

Ahmad, A., Islamic Surveys. A history of islamic Sicily, Edimburgh, Edimburgh University Press, 1975. [ Links ]

Amari, M., Biblioteca Arabo-Sicula, Torino-Roma, Loescher, 1880. [ Links ]

----------, Su le iscrizioni arabiche del Palazzo Regio di Messina, Roma, Reale Accademia dei Lincei, 1881. [ Links ]

----------, Storia dei Musulmani in Sicilia, Catania, Romeo Prampolini Editore, 1937. [ Links ]

Boas, M. "Hero's Pneumatica: A Study of Its Transmission and Influence", Isis, 40, 1949, pp. 38-48. [ Links ]

Bresc, H., & F. Giünta, "La naissance de la personnalité sicilienne", in H. Bresc & G. Bresc-Bautier (eds.), Palerme 1070-1492, Paris, Éditions Autrement, 1993, pp. 19-31. [ Links ]

----------, & A. Nef, Idrisi. Lapremière géographie de l'Occident, Paris, Flammarion, 1999. [ Links ]

Bresc-Bautier, G., & H. Bresc, "Scénographie du pouvoir", in H. Bresc & G. Bresc-Bautier (eds.), Palerme 1070-1492, Paris, Éditions Autrement, 1993, pp. 69-80. [ Links ]

Burnett, C., "The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century", Science in Context, 2001, 14, pp. 249-288. [ Links ]

De Simone, A., "La ville aux trois cents mosquées", in H. Bresc & G. Bresc-Bautier (eds.), Palerme 1070-1492, Paris, Editions Autrement, 1993, pp. 40-51. [ Links ]

Gabrieli, F., "Greeks and Arabs in the Central Mediterranean Area", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 18, 1964, pp. 57-65. [ Links ]

Grant, E., "Henricus Aristippus, William of Moerbeke and Two Alleged Mediaeval Translations of Hero's Pneumatica", Speculum, 46, 1971, pp. 656-669. [ Links ]

Haskins, C. H., "Further Notes on Sicilian Translations of the Twelfth Century", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 23, 1912, pp. 155-166. [ Links ]

----------, "The Greek element in the Renaissance of the twelfth century", The American Historical Review, 25, 1920, pp. 603-615. [ Links ]

----------, "Arabic Science in Western Europe", Isis, 7 (3), 1925, pp. 478-485. [ Links ]

----------, Studies in the History of Medieval Science, Cambridge, Mass., 1927 (2nd ed. [ Links ]).

----------, & D. P. Lockwood, "The Sicilian Translators of the Twelfth Century and the First Latin Version of Ptolemy's Almagest", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 21, 1910, pp. 75-102. [ Links ]

Houben, H., Ruggero II di Sicilia. Un sovrano tra Oriente e Occidente, Roma-Bari, Editori Laterza, 1999. [ Links ]

Ito, S., "The Medieval Latin Translation of the 'Data' of Euclid", Tokyo, University of Tokyo Press, 1980. [ Links ]

Jamison, E. M., Admiral Eugenius of Sicily, His Life and Work, and the Authorship of the Epistola ad Petrum and the Historia Hugonis Falcandi Siculi, London, Oxford University Press, 1957. [ Links ]

Lejeune, A., L'Optique de Claude Ptolémée dans la version latine d'après l'arabe de l'émir Eugène de Sicile, London, E. J. Brill, 1989. [ Links ]

Lorch, R., "Greek-Arabic-Latin: The Transmission of Mathematical Texts in the Middle Ages", Science in Context, 14, 2001, pp. 313-331. [ Links ]

Miquel, A., "Un géographe arabe à la cour des rois Normands: Idrisi (XII siècle)", in P. Bouet & F. Neveux (eds.), Les Normands en Méditerranée aux XI-XII siècles. Actes du colloque de Cerisy-la-Salle (24-27 septembre, 1992), Presses Universitaires de Caen, 2005, pp. 235-238. [ Links ]

Molinini, D., La géographie d'Idrisi-Roger. Une synthèse entre Orient et Occident, Mémoire de Master M2, Paris, 2007. [ Links ]

Murdoch, J. E., "Euclides Graeco-Latinus: A Hitherto Unknown Medieval Latin Translation of the Elements Made Directly from the Greek", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 71, 1967, pp. 249-302. [ Links ]

Plato Latinus, Phaedo, interprete Henrico Aristippo, L. Laurentius Minio-Paluelli (eds.), adiuvante H. J. Drossaart Lulofs (Corpus Platonicum Medii Aevi), London, Warburg Institute, 1950, vol. 2. [ Links ]

Rashed, R., "Les Traducteurs", in H. Bresc & G. Bresc-Bautier (eds.), Palerme 1070-1492, Paris, Éditions Autrement, 1993, pp. 110-117. [ Links ]

Rizzitano, U., "Ruggero il Gran Conte e gli Arabi in Sicilia", in G. Musca (ed.), Terra e uomini nel mezzogiorno normanno-svevo. Atti delle seconde giornate normanno-sveve, Bari, 19-21 Maggio 1975, Bari, Edizioni Dedalo, 1991, pp. 189-212. [ Links ]

Salah Ould Moulaye, A., L'apport scientifique arabe á travers les grandes figures de l'époque classique, Paris, Éditions UNESCO, 2004. [ Links ]

Taylor, R. C., "La diffusione delle scienze islamiche nel Medio Evo europeo", Isis, 81 (3), 1990, pp. 566-567. [ Links ]

* I would like to thank Roshdi Rashed, Ken Saito, Marco Panza, Hélène Bellosta, Davide Crippa and Alessandra Coccopalmeri for many helpful comments and suggestions. I am particularly grateful to Régis Morelon for his supervision during my Master thesis and his precious teachings.

1 See Abattouy, Renn & Weinig (2001), Burnett (2001), Haskins (1925) and Lorch (2001). Spain, mainly with Toledo, was an active center of transmission expecially during the second half of the xn th century.

2 Idrisi's Book of Roger inherits various elements from Ptolemy's Geography and from the works of other Arab geographers, but marks a real turning point with respect to the previous geography. It is not only a compendium, but a work which offers a new vision of the world. From Idrisi's work emerges what André Miquel has called the consciousness of living "la fin d'un rêve" (Miquel, 2005). This is why this work should be considered a good example in order to underline the importance of the cultural movement under Roger II. For a more precise analysis see Molinini (2007).

3 See Amari (1881), Houben (1999) and Rashed (1993).

4 See Amari (1937), and Bresc-Bautier & Bresc (1993).

5 See Gabrieli (1964).

6 See Molinini (2007), especially Chapter II.

7 Haskins & Lockwood, 1910, p. 90.

8 Haskins, 1912, p. 165.

9 Plato Latinus, 1950, p. 89 (my translation).

10 As observed by Haskins & Lockwood (1910) and Lejeune (1989), the Arabic version of The fable of Kalila and Dimna was probably a revision of the Greek version by Simeon Seith.

11 Lejeune, 1989, p. 5.

12 Lejeune, 1989, p. 11.

13 A previous edition was made in 1885 by Gilberto Govi.

14 For a detailed edition of the medieval Latin version of Euclid's Data (made from a Greek text) and a comprehensive discussion of the identity of the translator see Ito (1980), especially Chapter III. Ito's hypothesis is that the translator of the Data might be the same unknown translator of the Almagest and that the translation was made in Sicily before 1160. This conjecture seems to be supported by the fact that Haskins identifies the author of an existent Latin translation of Proclus' De Motu with that of the Almagest (see Haskins, 1927, pp 180-181).

15 Haskins, C. H. & Lockwood, D. P., 1910, p. 82.

16 Haskins & Lockwood, 1910, p. 100.

17 Rashed, 1993, p. 110.

18 Gabrieli, 1964.

19 Haskins, 1920, p. 615.

20 Various books of Arabic geographers are mentioned by Al-Idrisi in his Book of Roger. For a list of those books see Molinini, La géographie d'Idrisi-Roger. Une synthèse entre Orient et Occident, p. 52.

21 Burnett, 2001, p. 254.

22 See Molinini, 2007, La géographie d'Idrisi-Roger. Une synthèse entre Orient et Occident, Chapters II and V.

23 The language loss is a consequence of the instability which characterized the last period of William's reign. I am indebted to Régis Morelon for having drawn my attention to this interesting point.

24 Haskins, 1925, p. 485. See Lejeune (1989) for a short analysis of the quality of Eugenius' translation of Ptolemy's Optics.

Información sobre el autor

Daniele Molinini, doctor en Física por la Universidad de Bologna (Italia); actualmente realiza el doctorado en Filosofía de las matemáticas en la Université París Diderot (París 7), estudioso de física, de la filosofía de las matemáticas y de la transmisión del conocimiento en lengua latina (s. XII).