Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Estudios de historia moderna y contemporánea de México

versión impresa ISSN 0185-2620

Estud. hist. mod. contemp. Mex no.36 Ciudad de México jul./dic. 2008

Artículos

Cuauhtémoc regained

Christopher Fulton*

* Es profesor asociado del Hite Art Institute de la Universidad de Louisville, Kentucky. Correo electrónico: cfulton@louisville.edu

Resumen

Este ensayo continúa la investigación realizada en un artículo anterior también publicado en esta revista, examinando las representaciones artísticas de Cuauhtémoc en el periodo posrevolucionario, especialmente después de 1940, cuando la imagen del último emperador azteca fue concebida como un símbolo nacional. Muestra la manera en la que en este periodo las contradicciones internas, que eran latentes dentro del imaginario, llevaron a una controversia abierta y encendida sobre el significado y el empleo del símbolo de Cuauhtémoc.

Palabras clave: Cuauhtémoc, arte, indigenismo, nacionalismo, Edmundo O'Gorman, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, José Vasconcelos.

Abstract

This essay continues the investigation of an earlier article, also published in this journal, by examining artistic representations of Cuauhtémoc in the post–revolutionary period, and especially after 1940, when the figure of the last Aztec king became widely and variously deployed as a political and cultural emblem. The essay will describe how in the post–revolutionary era internal contradictions, which were latent within the imagery, broke into the open and ignited controversy over the meaning and use of the Cuauhtémoc symbol.

Key words: Cuauhtémoc, art, indigenism, nationalism, Edmundo O'Gorman, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, José Vasconcelos.

It was under the liberal regime of the nineteenth century that the memory of Cuauhtémoc was awakened by artists and intellectuals in search of symbols to represent the sovereign republic. Literary and visual evocations of the hero crested in the 1890s, amid a program of national integration and an upswell of patriotic feeling, but the currency of the image waned after century's turn with the redirection of official patronage from artistic expressions reliant on pre–Hispanic sources to projects executed in Neoclassical and Hispanist styles.

From about 1890 to 1925, a tide of pan–Hispanism swept through all of Latin America, stimulated in great part by concern over the expanding influence of the united states and the ebbing of Spanish power. This movement arose just as Cuauhtémoc attained maximum popularity, such that, in 1892, the year in which Leandro Izaguirre unveiled his glorious and immensely popular painting of the Torture of Cuauhtémoc, a second Columbus Monument was raised in Mexico City, fulfilling plans which had long gestated among conservatives and pro–Hispanists, and utilizing a sculptural model begun in 1856 by the Catalonian–born Manuel Vilar.1 In succeeding years, other Latin–American capitals erected their own monuments to the Spanish domination, including statues of the conquerors Pizarro and Cortés.2

Renewed pride in the Hispanic heritage put an end to vociferous condemnations of the conquest and colonialism, and dampened exaltations of the Aztec Empire and its leaders. Mexican writers began to declare themselves sons and daughters of Spain, and a spirit of compromise pervaded liberal and conservative circles. The heated dispute over Mexico's cultural origins, whether the nation rested on the foundations of Aztec pyramids or Spanish cathedrals, was largely resolved in the philosophy of mestizaje, which allowed Justo Sierra, the influential minister of Education from 1905 to 1911, to declare that the country was neither Spanish nor Indian but a unique fusion of the two, both racially and spiritually.3

The sense of Mexico's mixed identity prevailed long after the fall of the Díaz regime, and mestizofilismo became the watchword of the post–revolutionary period. Even ardent defenders of Indian rights, such as Manuel Gamio and Andrés Molina Enríquez, argued for the integration of Indians into the greater society and looked forward to a genuinely unified national culture.4 In most expressions of the time, the Indian was regarded in Romantic terms, not as an important actor in his own right but as the primeval source of the mestizo race, which was understood as the progressive agent in the nation's history, and it is against this integrationist form of indigenismo (defined by Villoro as a heightened consciousness of native culture and advocacy for the social and political rights of native peoples) that an admiration for native traditions spread through the fine arts community and left its stamp on the so–called Mexican Renaissance.5 It was also from this context that there emerged a renewed admiration for Cuauhtémoc, who was redeemed as an emblem of el pueblo mexicano.

Cuauhtémoc became the subject of renewed literary interest around 1915, when he was featured in Alfonso Reyes' richly descriptive prose poem Visión de Anáhuac.6 A few years later, he was recalled in the intermezzo of Ramón López Velarde's Suave Patria (1921), and there given the oft–repeated moniker "young grandfather" (joven abuelo).7 As described by Benjamin Keen, this contemplative poem portrays Cuauhtémoc as a catalyst binding Spanish and Indian elements into a peculiarly Mexican synthesis, in a literary parallel to the mestizaje proclaimed in political discourse. In Carlos Pellicer's Oda a Cuauhtémoc (1924), the emperor is extolled for his "soledad augusta", having been abandoned by other Indian tribes and left to his solitary fate, and he is regarded as the very embodiment of Mexico's originary past in a historical drama and analytical essay by the Marxist historian Alfonso Teja Zabre, Historia y tragedia de Cuauhtémoc (1929).8 In these literary productions, as well as in the popular film Cuauhtémoc (1918), directed by Manuel de la Bandera, the emperor appears as a unifying agent rather than the divisive force that warred against European influence and spent itself for the autonomy of native people.9

Cuauhtémoc's rehabilitation in the visual arts began in 1922, when the government ordered a bronze replica of the effigy from the Cuauhtémoc Monument (figure 1) —the colossal structure raised on Mexico City's paseo de la Reforma in 1887— to be delivered to Rio de Janeiro for the Universal Exposition marking Brazil's centennial of independence.10 The decision to send the statue was made by president Álvaro Obregón on the urging of his minister of Foreign Relations, Alberto J. Pani, who also commissioned a biography of the Aztec leader to accompany the gift.11 According to Pani, the figure of Cuauhtémoc was chosen because it symbolized the fraternity of Latin American countries and the common origin of the region's people.12 Familiar as he was with the Díaz regime's use of the image to represent Mexican unity and independence, Pani recalled the symbol in order to project these national values onto a larger continental stage, and in so doing to assert Mexico's leadership in the union of Latin States that was then being formed.13

It was left to the minister of Education, José Vasconcelos, to articulate the statue's meaning when he traveled to Brazil as Mexico's official representative to the exposition. In a formal address at the monument's inauguration, he extolled Cuauhtémoc's attempt to unite the Mexican tribes against the foreign invader and drew a connection between that historical event and the current situation in which Latin countries sought to band together against Yankee imperialism.14 He declared that all of Latin America will soon rise to a second independence, "the independence of the civilization, the emancipation of the spirit", as it emerged from a period of dependence on Europe, and he spoke exultantly of "these times of a great race which begins to dance in the light".

In this way, Vasconcelos did his best to validate the Cuauhtémoc symbol. But from the beginning he had opposed sending the statue to Rio, and had complained about the high cost of the bronze. this concern over expenditures belied, however, a conviction that the figure of Cuauhtémoc did not appropriately represent the aspirations of modern Mexico and Latin America, not only because it had once stood for the juggernaut of the Díaz regime, but because it ran counter to Vasconcelos' own views of the region's history and future destiny. Vasconcelos was an outspoken mestizofilia, with strong Hispanist preferences, and believed that the process of racial intermixing that had occurred in Mexico was a harbinger of the eventual blending of peoples into a universal human race. Miscegenation, he contended, made Mexico "the elect nation" for the unification of all humankind into a new type.15

Vasconcelos repudiated all forms of patriotism that divided populations rather than encouraging their integration, and so he objected to the decision to utilize the Cuauhtémoc symbol as an instrument of Mexican foreign policy and as a means of asserting the country's preeminence over other sovereign States. He furthermore chafed at the idea that Mexico and her sister nations were rooted in ancient history and could find common ground in the persistence of indian characteristics within their cultures.16 Therefore, when speaking at the inauguration ceremony, he avoided any suggestion that Latin Americans should reject the Hispanic and European heritage, as Cuauhtémoc had opposed Cortés, and refused to express faith in he redemptive power of native people. Instead, he presented Cuauhtémoc as a heroic figure whose defiant moment occurred at the end of Indian power and whose capitulation signaled the beginning of Spanish domination, which was itself eclipsed by the modern age.17

This interpretation of the Cuauhtémoc statue exposed a tension between Vasconcelos' universalist vision of history and the nationalist outlook of Obregón and his counselors. Although the president and minister of education would continue to work closely toward common goals for another year, it was ultimately a nationalist ideal which became enshrined in the ideology of the ruling party, and, as shall be seen, future battles over the Cuauhtémoc symbol would be mainly waged within the confines of this ideological field.

A strong interest in Indian people and their time–honored customs exerted a powerful hold on visual artists of the 1920s, as seen in the work of Francisco Goitia, Julio Castellanos, Ramón Cano Manilla and Gabriel Fernández Ledesma, and muralists, led by Diego Rivera, showed sympathy for native subjects and provided idealized views of pre–Hispanic cultures.18 Almost all artists, however, were reluctant to portray the indian as a motive force in the development of the nation, and only rarely did they glorify specific historical figures from the ancient world. This neglect may be partly ascribed to Vasconcelos' direct persuasions, though it was also the result of a shared sense that national progress is invested in the mestizo population, and that indigenous subjects are passive spectators of or at most auxiliaries in Mexico's triumphs and achievements. For these reasons, Cuauhtémoc seldom appears in paintings of the first generation of mexican muralists, and no significant mural from the early period is wholly devoted to him.19

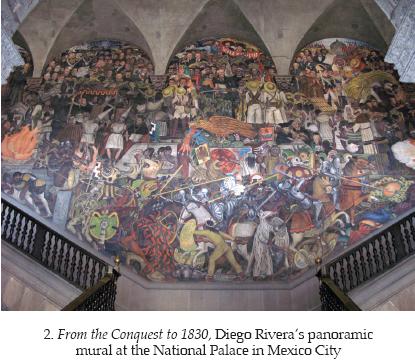

The sense of Cuauhtémoc's limited role within the pageant of Mexican history is reflected in Diego Rivera's panoramic mural (figure 2) at the National Palace in Mexico City. This grand work fills three enormous walls flanking the building's main stairs from the courtyard to the second level, and it is near the middle of the central mural, titled From the Conquest to 1930 (executed 1929–1930), that Cuauhtémoc is seen (figure 3) dressed in an eagle costume and identified by a banner with his hieroglyph of the descending eagle.20

The painting is divided into three registers showing the three great convulsions of mexican history —the Spanish Conquest, war of Independence, and Revolution —and the mural as a whole illustrates the rise of a free and just Mexico out of the conflicts of the past. To make this progress more apparent, Rivera distributed portraits of leading figures in these struggles along the painting's central vertical axis, beginning with Cortés at the very bottom, then proceeding upward to Cuauhtémoc, then the leaders of independence —Allende, Hidalgo and Morelos— and at the top three revolutionary martyrs —Emiliano Zapata, Felipe Carrillo Puerto, and José Guadalupe Rodríguez —accompanied by an industrial worker who points the way to the future.

Within the scheme, Cuauhtémoc represents the spirit of resistance which is later evinced by protagonists in the war of Independence and Revolution, and the painting indicates that it is his implacable resolve which will triumph in the deeds of the mestizo patriots shown in the registers above. Yet it is important to recognize that Cuauhtémoc is not himself an agent of this progress. He is rather cast as an index of a heroic quality embedded in Mexico's distant past and active in its historical present. His valiant but unavailing resistance to the Conquest does not propel Mexico forward, and Rivera, in keeping with views expressed by Vasconcelos, associates Cuauhtémoc with the destruction of the Aztec world, which stands at the end of Mexico's prehistory rather than at the beginning of its ascent to nationhood (this division is visually reinforced in the painting by the pyramid and eagle which decisively separate the two halves of the composition).

The art historian Ida Rodríguez Prampolini has called attention to the failed dialectics of Rivera's mural, in which class conflict plays no significant role and the unbroken advance of Mexican patriotism is delineated, and indeed Rivera's work on the mural coincided with his personal accommodation with the ruling party, which had already turned its back on socialist principles.21 In april 1929, he assumed directorship over the Academy of San Carlos, which was a government appointment, and in July he accepted the commission to decorate the National Palace. As this was a time when the regime began aggressive measures to suppress the radical left, Rivera's collaboration prompted his expulsion from the Communist Party in september 1929. Yet one must not assume that Rivera acted simply as a mouthpiece for the government and maintained no critical distance from it. Near the top of the mural is the figure of Álvaro Obregón, surrounded by strongmen and looking askance at a malevolent president Plutarco Elías Calles, a detail which insinuates that the former's assassination, which occurred in July 1928, may have been perpetrated by Calles and his inner circle, as commonly alleged.22

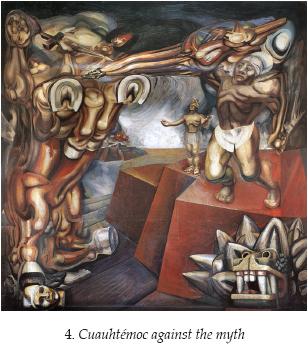

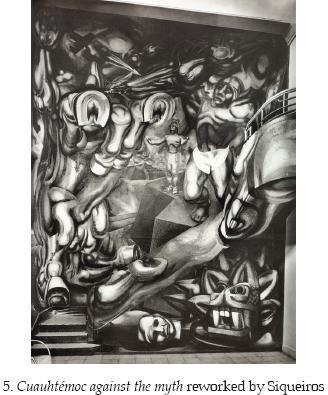

The first significant reappraisal of Cuauhtémoc in the visual arts was carried out by David Alfaro Siqueiros through a series of four murals and a half dozen paintings executed in the decade of 1941–1951.23 These are the first artistic reassessments of the Aztec hero since the Revolution, and they present him as a figure of enormous power and consequence. It is the second in the series, a mural titled Cuauhtémoc against the myth (figure 4), which most fully exploits the richness of the Cuauhtémoc image and best represents the artist's political and artistic intentions.

The painting is a theatrical production, a work of scenography. Developed at a private house in Mexico City (figure 5) soon after Siqueiros' return from exile in 1944 (in 1964, the image was reworked by Siqueiros and relocated to a building called the Tecpan of Tlatelolco, near the Plaza de las Tres Culturas), it framed a cantilevered stairway and was experienced by visitors ascending the stairs.24 The dynamic interaction between spectator and image was enhanced by the thick impasto of Siqueiros' experimental medium of piroxylin and various three–dimensional effects, including the mural's curved surface and the sculpted heads of a human and the serpent god Quetzalcóatl, symbolic of the defeated pre–Hispanic culture.

Upon a darkling plain, a mounted conquistador assaults an Aztec pyramid. The bodies of horse and rider are indistinguishably fused so that they appear as a single creature, a centaur–like beast with thrashing hooves which seem to multiply with their movement and are disposed in such a way that they resemble the fingers of a human hand. The cavalier grasps Christian implements of rosary beads and a cross–dagger —weapons of the spiritual conquest of the Americas— while a third arm brandishes a sword which flares like a torch —referencing the military conquest of the Indian nations—. As witness to this scourge, the spectator is put in the shoes of the ancient Aztecs, who at the Conquest were uncertain of the precise nature of the strange monstrous forces besieging them. Opposite the centaur is a muscular Cuauhtémoc, standing undaunted on the pyramid and brandishing an obsidian tipped spear (as does the heroic figure of the Emperor atop the pyramid–shaped base of the nineteenth–century Cuauhtémoc monument on Paseo de la Reforma); he has already wounded his foe in the belly, and now aims a second thrust at the beast's heart. Beside him is a faceless Moctezuma, who hopes to pacify the menace and opens his arms to implore the gods for salvation.

The high drama appeared still more intense when the painting was viewed in its original setting. Visitors approaching the stairs initially stood directly below the centaur's menacing hooves, and having ascended to the landing, found themselves shoulder to shoulder with Cuauhtémoc, from which position they could, like him, face the beast head–on.25 Their progress up the stairs corresponded to a raising of consciousness, with terror before a seemingly invincible force giving way to a clearer measure of the threat and the possibility of defeating it.

The painting's title alludes to the Emperor's determination to fight on, even in the face of the myth which foretold the doom of Anáhuac, and which Moctezuma had taken to heart.26 In a wider sense, this is the myth of historical predestination and impotence, which brought destruction to the Aztecs, which condemned Mexico to three–hundred years of servitude under spanish rule, and which left the country vulnerable to foreign interventions and capitalist domination in the modern period. It is a myth perpetuated by Mexicans themselves, as described in Samuel Ramos' hugely popular El perfil del hombre y la cultura en México of 1934, and it represents a debilitating influence which Siqueiros attempted to expose and overcome through his mural.

Already in 1944, Mexico showed signs of rejecting the myth by entering the Second World War and confronting the behemoth of fascism. It was naturally a source of pride to have joined the community of nations in combating a great evil, but participation in the war had special meaning for Mexico, because it drew the country out of its political and psychological isolation, and gave it a presence on the world stage. The country's involvement in the war was strongly applauded by Siqueiros, who had been committed to the struggle against fascism since his military service in the Spanish civil war and had worked devotedly for the National League against Fascism and War (Liga Nacional contra el Fascismo y la Guerra).

Mexico had further acquitted itself prior to the war through the bold initiatives of president Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–1940), who defied the United States and European powers by nationalizing the petroleum industry, placing other industries under governmental control, and accelerating the redistribution of land. These actions were widely perceived as a national victory against foreign encroachments and equated with Mexico's triumph over the european intervention in 1867, and just as that earlier feat had inspired artistic representations of Cuauhtémoc, so did the policies of the Cárdenas administration revive patriotic feeling and stimulate interest in the Aztec hero.27

Siqueiros initially entertained two primary thoughts about the mural's meaning. First and foremost, the mural exuded the spirit of anti–fascism and encouraged all mexicans to fight against the global threat. Second, in an appeal to the radical left, it urged the defense of socialist principles against deviationist tendencies and imperialist interference, particularly from the United States.28 This understanding of the symbol was expressed by the labor leader Vicente Lombardo Toledano, who delivered a speech at the mural's inauguration in which he associated Cuauhtémoc's conflict with the struggle of organized labor.29 Thus, from the start, the mural was subject to more than one interpretation, and in 1951 Siqueiros further extended its meaning by claiming that the symbol of Cuauhtémoc applies to all people who resist Western colonialism: "I see in Cuauhtémoc a prototype of Mao Tse–Tung […] the leaders of the Viet Minh, and the fighters for the nationalization of Iran's oil".30 With this odd statement, Siqueiros construed the figure of the Aztec king as a universal symbol for the world's oppressed races and third world peoples, and indeed for subordinated people wherever they are found, including the industrial proletariat in their contest with bourgeois capitalism.

The style of Cuauhtémoc against the myth is significant in its own right. The painting forcefully rejects "folklorism" and academicism by which artists had portrayed indian subjects according to stereotyped formulas.31 It is purged of anecdote and sentimentality, and executed in a bold monumental style, with figural proportions based on the hewn character and compact masses of pre–Hispanic art, while its surface if variably textured to give it extra potency.32 The house that originally held the mural functioned as the headquarters of an organization known as the Center of Modern Realist art (Centro de Arte Realista Moderno), which was founded by Siqueiros to instill a revolutionary spirit into art, and at the mural's unveiling, Siqueiros issued a manifesto on behalf of this organization which declared that Mexican art had lost sight of its social mission, and that a new realist art devoted to humanistic principles must be devised to meet the needs of the day.33 The Center was established to foment this new kind of painting and reconstitute muralism as a social revolutionary movement, and Cuauhtémoc against the myth was produced as the first exemplification of these goals.

But there is no evidence to suggest that Siqueiros did wished to proclaim Cuauhtémoc as a representative of the indian people as such or to express support for the separateness of native communities. He was, in fact, deeply suspicious of most forms of indigenism, especially when couched in "folklorism" and "archeologism". As a devout communist, he foresaw world–wide revolution carried out by the working classes, and rejected chauvinistic rhetoric which appealed to a sentimental ideal of the indígena. It was indeed exactly this unwelcome proclivity which Siqueiros had earlier critiqued in the painting Ethnography (Etnografía) (1939), which shows a campesino wearing a pre–Hispanic mask, his true identity hidden and his field of action narrowed by the stereotypes thrust upon him. That work exposed the harmful effects of an indigenism which condescends to native people by treating them as romanticized objects rather than as living subjects and agents of history.

Siqueiros' attitude toward the Indian population was informed by communist thought. In the 1910s, Lenin had planted the principle of the right of self–determination for secondary nationalities, and the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) fell in line with this doctrine by supporting demands for native autonomy and backing President Cárdenas' land reform policies. Political rights for indigenous communities were proclaimed at the First Communist Pedagogical Conference (Primera Conferencia Pedagógica Comunista) of February 1938, and reasserted in 1941 by Ramón Berzunza Pinto, president of the PCM's Subcommission on Indigenous people (Subcomisión Indígena).34

The vehemence of this support abated in the early 1940s, however, with the outbreak of war and the imperative to industrialize the country. And even after the war had ended, Leftists continued to press for industrialization and national unity and gave scant attention to the special needs of native peoples. Their cultural "otherness" was attributed to economic underdevelopment and exploitation, and they were increasingly treated as members of a single class of the downtrodden, which included the urban poor and impoverished campesinos.35 The proposed remedy proposed for the cuestión indígena was the rapid integration of natives into the corporatist economy and national polity, and this approach, taken up by most spokesmen of the Left, aligned rather closely with the economic objectives of the Ávila Camacho and Álemán governments.36

It is hard to determine Siqueiros' precise stance on these issues because he rarely addressed them straight on. As incisive as the painting Ethnology may be, Siqueiros —in parallel to the PCM and the mexican socialist movement as a whole— does not seem to have resolved the problem of the indigenous subject in his art or political thought, and as a result tensions arise within his treatment of the Cuauhtémoc symbol. The noble defender of Tenochtitlan is presented as an exemplar for various political struggles except for the specific conflict of indigenous people with Western values and systems, the very cause in which the emperor had in real life fully committed himself. In this sense, the symbol remains incomplete and in contradiction with the history of its own subject.

Despite these tensions within Siqueiros' treatment of the Cuauhtémoc symbol, his mural portrays an empowered indian subject and implicitly contradicts the stigma of weakness and submissiveness commonly assigned to aboriginal people.37 Unlike Rivera's work at the National Palace, in which the emperor is integrated within a historical pageant where whites assume leading roles, Siqueiros' hero stands determinedly apart from this procession, and his face–off with the conquistador emblematizes a rejection of the myth of historical progress which had been defined by the country's intellectual elite and tended to tread roughly over native people and their ageless cultures.

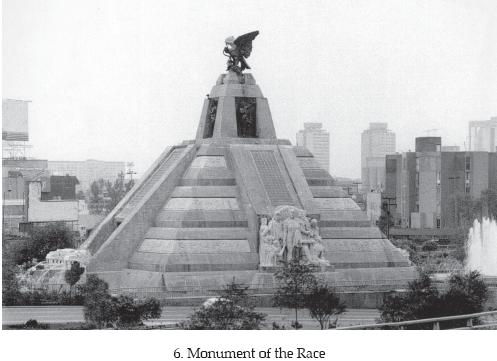

Siqueiros' interest in Cuauhtémoc coincided with the development of a more radical and separatist indigenismo, whose apostles —though not Siqueiros himself— began to encourage native people to resist the pressures of Occidental culture and strive for a measure of autonomy and self–determination.38 This strain of indigenism found occasional support at the highest levels of government: it was endorsed at the First inter– American Indigenist Congress at Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, from which emerged the Inter– American Indigenist Institute and eventually, in 1948, Mexico's National indigenist Institute (INI); and in 1940, it was recognized in the Monumento de la Raza (Monument of the Race), a huge concrete pyramid put up in Mexico City under the direction of Francisco Borbolla and Luis Lelo de Larrea (figure 6).39 At the base of this structure was placed a large stone sculpture of a bellicose Cuauhtémoc leading his desperate people to their final stand, and at the top were set four of the six bronze reliefs which had been made by Jesús F. Contreras for the Paris World's Fair of 1889, and which portrayed three early Aztec kings plus the last regent, Cuauhtémoc.

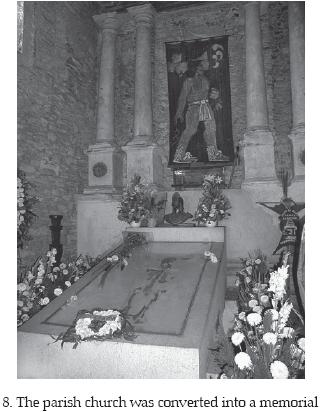

A spirit of resistance became manifest in a bitter and long–lasting controversy which broke out over the alleged discovery of Cuauhtémoc's skeletal remains. The fracas began on september 26, 1949, when, at the small Chontal village of Ixcateopan, in the rugged hill country of Guerrero, a group of local citizens in partnership with the archeologist Eulalia Guzmán unearthed below the altar of the parish church a jar of bones, which they identified as belonging to their legendary forebear Cuauhtémoc (figure 7).40 This amazing discovery seemed to confirm what was described in a set of documents which had come to light in February of the same year, and told of the retrieval of Cuauhtémoc's body soon after his hanging in 1525, its transportation to Ixcateopan, and its subsequent interment beneath the church under the direction of the missionary fray Toribio de Benavente, known as Motolinía.

News of the discovery of the bones spread quickly, and soon peasants from all over the region flocked to the village in tears of jubilation. A flag was draped over the site, an honorary guard posted above the excavation pit, and the next day, the state governor, general Baltasar R. Leyva Mancilla, arrived with his retinue to proclaim the authenticity of the finds.41 The wave of enthusiasm continued to roll across Mexico and engulfed the entire country in a Cuauhtémoc fervor. On october 12, Mexico's Día de la Raza, the legendary king became a focus of celebrations. At Ixcateopan, 7 000 people gathered to witness the conversion of the church into a state–operated shrine, and the church's final mass was given in honor of the last emperor.

For many, the unearthing of the bones fulfilled a longing to reclaim the country's ancestral past and affirm the millenarian promise that all Mexicans, because of their common origin, shall be united in a single community of shared interests and values. The bones brought Mexicans into contact with the country's autochthonous origins, its truest self summoned forth from hallowed ground, what Guillermo Bonfil termed "deep Mexico", versus "imaginary Mexico", which is the idea of a progressive nation conceived by the country's intelligentsia and endorsed by the ruling group.42 Octavio Paz explained the psychological importance of the discovery, and its retrospective and prospective dimensions, when he wrote in The labyrinth of solitude of 1950: "the mystery of Cuauhtémoc's burial place is one of our obsessions. To discover it would mean nothing less than to return to our origins, to reunite ourselves with our ancestry, or break out of our solitude. It would be a resurrection".43

Yet even before the bones actually appeared, doubts had been raised about the veracity of the legend of Cuauhtémoc's burial at Ixcateopan, and on August 18, 1949, a commission organized by the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) released a report which condemned the documents attesting to the burial as modern forgeries. This verdict made the providers of these records appear ridiculous, if not actually deceptive, so that the subsequent revelation of the bones, in the very place where they were supposed to be, was greeted as a complete vindication, and, in a more philosophical vein, as a victory of Mexico's true history, rooted in oral traditions and folk wisdom, over the faithless book–learning of institutionally based scholars.

The new archeological evidence occasioned a second review, headed by Ignacio Marquina, director general of INAH. However, the Marquina Commission, which filed its report on October 16 (the report was released to the press three days later), sustained the negative conclusions of its precursor, by stating that the recovered bones were spurious and had been planted under the church in recent times, and that, as previously suspected, the documents were equally false, invented around 1900 by the villager Florentino Juárez, who was possibly aided by Vicente Riva Palacio, a well–known intellectual and politician of the Porfirian era and promoter of the Cuauhtémoc symbol.

The commission's assessment set off a firestorm of protest from those directly involved in the excavation and believers all across the country. Articles and editorials defended the excavation in the popular press, and a number of activities were held to celebrate the emperor and his recent exhumation, including radio shows, musical and dance performances, and educational teachings, while the National Institute of Fine Arts (INBA) officially declared 1950 the "Year of Cuauhtémoc".44 With time, Cuauhtémoc's name was bestowed upon innumerable buildings, streets, parks, dams and towns.

Teachers and educators were especially quick to embrace the Cuauhtémoc symbol and rally around the archeological discovery.

The Secretary of Public Education from 1949 to 1951, Manuel Gual Vidal, while maintaining public skepticism toward the finds, took actions to promote the legend and exhumation. Meanwhile, instructors sponsored events in celebration of the ancient monarch and gave classroom lessons about his laudable deeds. On november 18, 1949, a parade of 10 000 torch–bearing students, led by the director of Secondary Instruction, Antonio Galicia Ciprés, marched from the Plaza de la Constitución to the Cuauhtémoc Monument, and there listened to a series of midnight lectures on the importance of the Ixcateopan discovery. A week later, on November 26, Galicia Ciprés guided teachers on a civic pilgrimage to the village. And of more lasting consequence, Cuauhtémoc's heroism and virtue were inscribed in popular schoolbooks, which also perpetuated the legend of his burial at Ixcateopan.45

Prominent figures with indigenist sympathies were eager to be counted among the excavation's defenders. Diego Rivera sharply criticized the Marquina Commission in the public press, and visited with Guzmán at the site, where he made a series of drawings from the remains in an attempt to reconstruct Cuauhtémoc's physical appearance.46 Alfonso Quiroz Cuarón, chief of the Department of Special Investigations at the Banco de México, headed an independent team of investigators which rebutted the negative review in a hastily prepared report of November 23, 1949. On april 7, 1950, ex–president Lázaro Cárdenas visited the town, accompanied by government officials and his teenage son named Cuauhtémoc, and there pronounced his belief in the remains. Vicente Lombardo Toledano opened his presidential campaign on January 13, 1952, with a speech at the village. "Father Cuauhtémoc", he declared, "you have left us, with your conduct and your sacrifice, an eternal mandate to defend Mexico against the oppression that comes from without".47 Even the Senate of the Republic stood behind the discovery and voted to erect a monument to the revered ruler.

Public outcry against the Marquina Commission incited secretary of Public Education Gual Vidal to call for another review.48 The group he appointed in January 1950 became known as the Great Commission (Gran Comisión), because it was filled with nine intellectual luminaries ("los supersabios", as they were called), including Manuel Toussaint, Arturo Arnáiz y Freg, Manuel Gamio, Alfonso Caso, and José Gómez Robleda. But contrary to Gual Vidal's hopes for an overturning of the earlier reviews, in February 1951, the Great Commission issued another harsh judgment, concluding that a giant hoax had been perpetrated with forged documents and modern bones, and scolding the archeologist Guzmán for sloppy fieldwork.49

The Ixcateopan controversy pitted two wings of indigenism against each other. On one side was a moderate, integrationist concern for native communities, which had been blessed by the government since the 1930s, and was well ensconced in educational and research institutions. On the other side was a radical, separatist indigenism, which gained steam in the 1940s, and might on occasion rise to challenge the ruling center.50 The conflict between these two positions and their umbrageous advocates overlaid the Ixcateopan debate and gave it a particular testiness. Thus, the major part of the academic community and political bureaucracy, including president Alemán, remained unmoved by emotional appeals on behalf of the finds, and refused to acknowledge even their symbolic value. Meanwhile, defenders of the excavation accused these groups from the metropolis of having entered a conspiracy to subjugate indigenous people and rob them of their age–old symbols. Theirs was an act of cultural expropriation no less offensive than the foreign economic and political intrusions which the country had withstood for centuries. Professor Guzmán and others issued a stream of books and articles condemning the various review commissions for their betrayal. As charged by Moisés Mendoza, the intellectuals on the Great Commission had discredited the remains in order to exert control over which persons should be awarded fame, and in a wider sense to propagate "the history, the philosophy, and even the law which were shaped by the conquistadors, and afterwards employed to mark out the servile and abandoned [within the general population]".51 In the terms of this discourse, Cuauhtémoc's obduracy to the spanish conquest was seen as a model for contemporary resistance to an urban elite and its exclusionary view of national history. The external power which the nation now confronted did not consist of invading armies from overseas or robber barons from the north but the institutional center operating out of Mexico City.

As impossible as it may seem, at a still later date, one more commission was appointed to look into the finds. Called by president Luis Echeverría in January 1976, and entrusted to Guillermo Bonfil, general director of INAH, this fourth group comprised experts from different areas of study —archeology, physical anthropology, forensic medicine, history, colonial architecture, and oral history— who, having reexamined the literary and archeological materials and completed another excavation at the site, echoed the negative conclusions of the earlier commissions.52

The persistence of the belief in Cuauhtémoc's remains is mainly attributable to the strong emotional appeal of the discovery, which affirmed the credo of Mexican uniqueness, based, as it was said to be, on the Aztec inheritance. Yet other, less disinterested factors contributed to the propagation of the legend. A recent study by Paul Gillingham has uncovered the personal motives of Florentino Juárez, the inventor of the documents which started the hoax, and those of his grand–nephew Salvador Rodríguez Juárez, who brought the documents to light in February 1949, and devoted himself to their defense.53 Both men were inspired by a pride in their locality, and wished to insert their humble village within the national saga of the Conquest and associate it with the adored hero Cuauhtémoc (Florentino's documents claimed that the Aztec leader was not born a Mexica from the altiplano but a Chontal from Guerrero). Yet it also appears the both men sought to realize material profit from the legend, which they hoped would bring economic benefits to the town and raise their own stature in the community.54 Salvador used the excavation to gain political standing. His Committee for the Authenticity of the Remains of Cuauhtémoc (Comité Pro–Autenticidad de los restos de Cuauhtémoc) not only advocated for the bones but functioned like a political machine and was able to control local politics for much of the 1950s.

It is hard to know whether the archeologist Eulalia Guzmán willingly collaborated in the hoax or succumbed to massive self–deception brought on by an intense desire to verify the legend and support indigenist beliefs which underpinned it. But her bias and gullibility may also be seen as excrescences of the applied archeology in which she had been trained and in which she operated.55 Her uncritical acceptance of oral tradition and her open advocacy for the villagers at the expense of duty to scientific method appear to have been misguided attempts to emulate the political engagement of her mentor, Alfonso Caso, who was both a distinguished academic and leading voice within the indigenist movement. The emphasis that he gave to the subjective perception of communities in defining themselves as indio or mestizo certainly influenced Guzmán's methodology, hence the heavy weight she placed on local folklore in confirming the remains. But Caso, a wiser and more cautious scholar, saw that his pupil had forfeited her impartiality, and as a member of the Great Commission he leveled strong criticism against her flawed and unprofessional procedures.56 Guzmán and Rodríguez Juárez presented themselves as champions for Ixcateopan and its native population, and thereby gained approval at local and national levels. Guzmán was particularly fêted. The town's main square was renamed after her, and as recently as 2005 a postage stamp was made in her honor. Most of the peasants of Ixcateopan and surrounding villages idolized Guzmán and Rodríguez Juárez, and clamorously endorsed the discovery of the bones.57 Their support was fed by patriotism and local pride, and by an expectation that the attention brought to the village would put it in a better position to negotiate for favors from the government and other institutions, and that the town might reap economic rewards as a tourist destination.58 Art played a role in this self–promotion. Soon after the excavation was completed, the parish church was converted into a memorial (figure 8) and decorated with a bronze bust and paintings, while a statue was erected out–of–doors. The town later established a Museum of the Resistance, and in recent years costumed dances have been performed to the delight of visitors.59

The Ixcateopan discovery placed Cuauhtémoc once again in the national spotlight, and in the early 1950s, a spate of publications gave more substance to the image. José López Bermúdez, general secretary of the PRI, celebrated the hero and his exhumation in the lengthy poem Canto a Cuauhtémoc (1950), which contains a section titled "Cuauhtémoc contra el mito", perhaps inspired by Siqueiros' mural. This portion of the poem commends Cuauhtémoc's valor in the face of frightful odds and before the fiction of Mexican weakness and vulnerability, and in the spirit of Molina Enríquez, it acclaims Cuauhtémoc as father and originator of a new man, "el primer hombre nuevo", who will emerge to create a revitalized society built on ancient traditions and virtues.60

Other books from these years include Salvador Toscano's posthumously issued biography of 1953, which displays a nostalgia for Aztec civilization and identifies the perdurance of pre–Hispanic traits in the blood of the mestizo, and in the language, diet and temperament of the modern Mexican.61 Another publication, from 1952, is Adolfo Anguiano Valadez's Cuauhtémoc: defensor de su cultura, which is dedicated to Eulalia Guzmán, "espíritu–abnegado, visionario y patriótico". In agreement with Siqueiros' thoughts about the wider implications of the Cuauhtémoc symbol, Anguiano Valadez declares that the hero has universal appeal for all who resist enslavement and oppression.62 And a poem of 1955 by Raúl Leiva Casts Cuauhtémoc as an eternal symbol of "deep" Mexico and its unbreakable will to resist the foreigner.63

Black with coagulated blood and age,

Cuauhtémoc is a quercine warrior,

an eagle afire,

taciturn, a flint, a jadestone of death.Cuauhtémoc is the village, the earth, the horizon,

the summit of Anáhuac,

the indomitable ferocity

opposed to the invader, flag of his race.[Negro de sangre coagulada y vieja,

Cuauhtémoc es un roble combatiente,

un águila de fuego, taciturna,

un pedernal, un jade de la Muerte.Cuauhtémoc es el pueblo, la tierra, el horizonte,

la suma del Anáhuac,

la indomable fiereza

que al invasor se opone, bandera de su raza.]

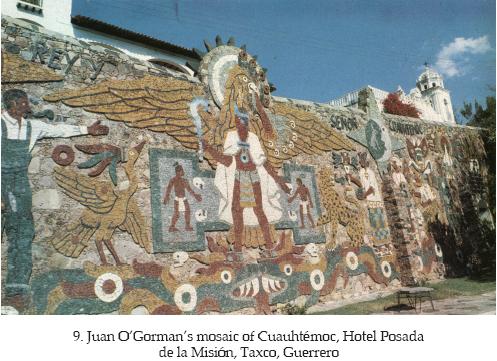

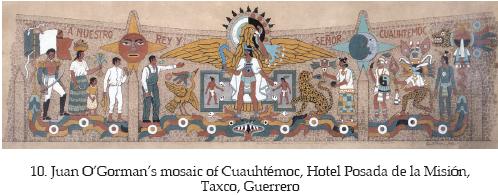

Visual artists of the 1950s joined this chorus of praise.64 In Taxco, the capital of the state of Guerrero, Juan O'Gorman created a mosaic relief of Cuauhtémoc (1955–1956) for the Hotel Posada de la Misión (figures 9–10).65 He described the work as a large "ex voto," and across the top of the relief he placed the inscription, "To our king and lord Cuauhtémoc" (A nuestro rey y señor Cuauhtémoc), pointing to the loyalty which modern citizens, especially natives of Guerrero, still felt toward the historical figure. O'Gorman further stressed Cuauhtémoc's importance for the region by constructing the relief with natural stones gathered from the state and hiring local artisans to work on the project.66

While the mosaic is arranged in a triptych and resembles a religious altarpiece, it is filled with pagan imagery. Running underneath the human figures is the outstretched serpent Quetzalcóatl, principal deity of the pre–Hispanic peoples and a central figure in Mexico's mythopoetic origins. At the center stands Cuauhtémoc against an ancient ballcourt and eagle, which is the chief emblem for both the Aztec empire and Mexican nation as well as his personal hieroglyph. To his right are figures from the modern era —the patriot Vicente Guerrero, a Guerrerense peasant family, and an industrial worker— and to his left figures from the ancient past —a woman, a soldier, a dancer–priest, and a ball player— while sprouting from the serpent's twin tails are the Mexican flag and an Aztec standard. The inescapable message is that Cuauhtémoc's authority extends across historical divisions and commands the same respect today as it did in ancient times. This is completely in keeping with literary homages to the Aztec king as well as the views of adherents to the Ixcateopan discovery (O'Gorman himself lent credence to the excavation and sympathized with its defenders).

Since the late 1940s, Cuauhtémoc has become ever more closely associated with Mexico's indigenous people and their cultural aspirations. This tendency is reflected in performances of the Danza de la Conquista, which reenact the fall of the Aztec empire. In a recent study of the dance, Carlo Bonfiglioli Ugolini has shown that its spread to numerous villages across Mexico and the sharing of characteristics of the performance among towns within certain areas have had the effect of strengthening regional cultures.67 The dance fosters solidarity among rural populations and allows indigenous peoples to define their cultural identity through the portrayal of Native American and Western characters.

A pro–Indian emphasis was introduced into variants of the dance in the later nineteenth century, when Cuauhtémoc became enthroned as a symbol of Mexican resistance to foreign domination, and Bonfiglioli Ugolini has found that at this time the emperor became a central figure in dance performances.68 At Santa Ana Tepetitlán, near Zapopan, Jalisco, he was presented in opposition to Cortés, who was assimilated with both Columbus and the North American invader of 1847.69 His prominence was further raised in the 1940s and 1950s, in the wake of heightened interest in the figure and the apparent discovery of his bones. At Tlacoachistlahuaca, a village on the Costa Chica in the state of Oaxaca, where the dance was introduced in 1949, the emperor is featured as the main protagonist, and at a pivotal moment is made to kill Moctezuma, by which he emerges as vindicator of Aztec weakness and depravity. The dance culminates in Cuauhtémoc's death (figure. 11) and ceremonial burial, and his transfiguration into a symbol of the nation and its indigenous people.70

Bonfiglioli Ugolini has also found that in recent decades, in Tlacoachistlahuaca as well as towns throughout the republic, the danza has become increasingly performed by indios alone, without the participation of mestizos. He states that this is evidence of a growing lack of interest in folkloric customs among white–skinned people, but it may also reflect their disenchantment with indigenous symbols like the figure of Cuauhtémoc, and conversely a growing sense among indios that these symbols are properly theirs.

Cuauhtémoc's reemergence in the 1940s was an act of resistance to liberalism, advanced capitalism and the bureaucratic nation state. It was a revolt against social ideals which had been introduced into Mexico during the Porfiriato and which artists and intellectuals of that era had associated with the last emperor. Rather than glorifying the centralized state, the Cuauhtémoc symbol has increasingly fallen into the hands of leftists and is widely used to attract support for dissident causes. This trend began with Siqueiros and was continued with Eulalia Guzmán, who with her supporters chose to publish in the journal Cultura Soviética.71 Leftist authors have since been greatly enamored with Cuauhtémoc. A poem by Máximo Simpson connects his final struggle and martyrdom with the 1968 massacre of students at Tlatelolco,72 and Cuauhtémoc frente a Cortés by Estrada Unda, a journalist and government official who devoted himself to the defense of labor, depicts the Aztec hero as a unifier of classes in the midst of social conflict.73 More recently, the symbol has been commandeered by revolutionary groups such as the Zapatista Army for National Liberation (EZLN), most active in the state of Chiapas, and the Maoist Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR), operating in Guerrero state.74

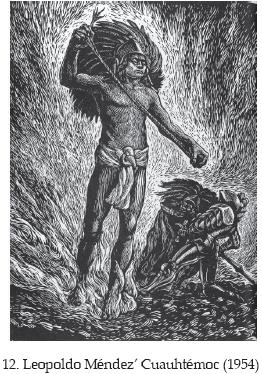

The radicalized artist Leopoldo Méndez belongs to this tradition. His arresting print (figure 12) of 1954 shows an apparition of the young Cuauhtémoc, sheathed in fire and light and readying a sling with his powerful hands, while below a bewildered conquistador and indian ally cower in fear. The print is informed by the artist's socialist politics. It presents Cuauhtémoc as an emblem of the Indian people and working classes who have recovered their strength to oppose Western imperialism and militarism —denoted by the armor–clad conquistador—, and domestic elitism and privilege —denoted by the sumptuously garbed cacique.

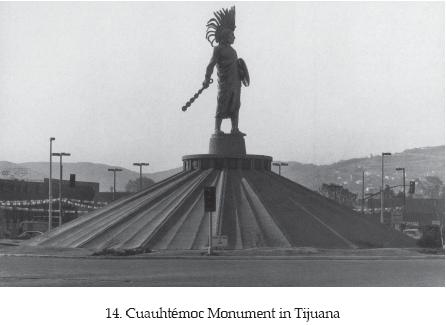

In recent decades, artistic portrayals of Cuauhtémoc are often directly associated with the general populace. It is not unusual to find statues of the emperor in working class neighborhoods or adjacent to buildings of government institutions which tend to the needs of the disadvantaged. Around 1983, for example, a bronze figure of the emperor (figure 13) was posted in front of the new Municipal Palace of Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl, a dense urban area which emerged from squatter's camps on the outskirts of Mexico City.75 Similar statues adorn the plazas and town halls of numerous regional centers, particularly in the state of Guerrero. In at least two places along the northern border, monumental sculptures of Cuauhtémoc stand guard against the North–American intruder. The Ciudad Juárez statue portrays him in royal dress, holding a staff of Aztec authority, while in Tijuana (figure 14), he is shown as a fierce warrior–king, armed with shield and macana, and wearing the same garments which are seen at the Cuauhtémoc monument of Mexico City.

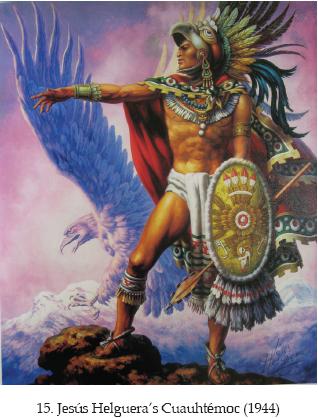

Within the realm of popular art, the most commonly reproduced images of Cuauhtémoc are derived from two paintings by the illustrator Jesús Helguera, one titled Cuauhtémoc (figure 15) and the other Eagle Warrior (Cuauhtémoc), and both made around 1944, as part of a series of Aztec subjects which the artist developed for calendars issued by Galas de México. The fleshy quality of the figure seems to be inspired by Jesús F. Contreras' bronze relief of 1888–1889, but as in Helguera's other images of indian subjects, Cuauhtémoc exemplifies an ideal of indigenous strength and beauty, in contradiction to the long tradition of criticizing the fallen condition of native people. Helguera's two Cuauhtémoc images are enormously popular even today, and ubiquitous throughout Mexico, translated into such mass produced mediums as posters, calendars, beach towels and cast aluminum statuettes.76

Unlike the Cuauhtémoc images by Siqueiros and Méndez, Helguera's highly embellished depictions lack any revolutionary content or suggestion, and can be understood in a purely patriotic sense. Similarly, as the hero of Tenochtitlan has been adopted by radical groups, official organs of power have retained the image as a symbol of unified Mexico, and it may be suggested that these authorities have planted the imagery among the working classes in order to stimulate patriotic feeling and attract popular support for the institutions of State. Federal and state governments continue to commission public statues of the emperor, whose head is still used as the logo of the commercial enterprise Cervecería Cuauhtémoc, and whose profile adorns the passenger jets of AeroMéxico.77 Government officials frequently appeal to Cuauhtémoc when cloaking themselves in indigenist and tercermundista rhetoric. President Luis Echeverría, who appointed the last of the Ixcateopan review commissions, once called Cuauhtémoc "the wellspring of organized resistance against dependency and colonial exploitation" (note the key word "organized", which implies government managed efforts), and in a campaign speech at Ixcateopan, he exhorted the young to imitate Cuauhtémoc (once again in paternalistic language): "to manifest his statesmanlike character the youth of our century should find paths of inspiration and the courage for their acts, not for absurd violence which shakes the creative order of our era, but rather to channel themselves […] in defense of the republic's highest ideals".78

Although center and periphery share an affection for Cuauhtémoc, tensions exist between the government's use of the figure to sustain a nationalist ideology and the adoption of the symbol by dissidents and champions of subordinated groups. in this situation, the meaning of the image has become increasingly diffuse and imprecise. What was in the late nineteenth century a lucid expression of the independent and unified nation is now associated with an array of disjointed and often contradictory hopes and sentiments. The symbol is caught in a dialectic of "top down" and "bottom up" cultural processes, through which it is continually reinterpreted and transformed.

1 Manuel García Guatas, "Colón en sus pedestales", in Actas del XIII Congreso Nacional de Historia del Arte, v. 2, Granada, 2000. [ Links ] Statues of the Navigator, including the second of the columbus monuments erected in Mexico City, proliferated across Latin America in 1892, the fourth centenary of the discovery.

2 José Antonio Gamarra Puertas, Humillante monumento a Pizarro, Lima, TecniGraf, 2002; [ Links ] Rodrigo Gutiérrez Viñuales", El papel de las artes en la construcción de las identidades nacionales en Iberoamérica", Historia Mexicana, 53, 2003, p. 341–390. [ Links ]

3 Justo Sierra acclaimed Cuauhtémoc in México social y político (1889) and Evolución política del pueblo mexicano (1900–1902). The spirit of compromise met little resistance within the liberal camp, as several of its staunchest apostles expired in the 1890s, including Riva Palacio, Altamirano, and Prieto.

4 Manuel Gamio, Forjando patria, 2nd ed., Mexico City, Porrúa 1960, p. 97–98. [ Links ] Alan Knight, "Racism, Revolution, and Indigenismo: México, 1910–1940", in The idea of race in Latin America, 1870–1940, ed. Richard Graham, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1990, p. 71–113, [ Links ] argues that Porfirian approaches to the "Indian problem", which were openly racist and called for forced acculturation, lived on in the post–revolutionary era and were accepted even by self–declared indigenists.

5 For example, Andrés Molina Enríquez, "El problema de la colonización nacional", Revista de Economía Rural, Mexico City, undated (c. 1920), p. 27–38, [ Links ] where it is argued that the Indian soul lay deep within the mestizo; cfr. his Juárez y la Reforma, 4th ed., Mexico City, Libro–Mex, 1961 (originally published 1905), esp. p. 325, 341, [ Links ] and Los grandes problemas nacionales, Mexico City, A. Carranza, 1909, infra. Luis Villoro defines indigenismo in Los grandes momentos del indigenismo en México, Mexico City, El Colegio de México 1950, p. 9.

6 Alfonso Reyes, Visión de Anáhuac, San José (Costa Rica), El Convivio, 1917. Later in life, Reyes contributed the preface to a book on Cuauhtémoc by José López Bermúdez (discussed below). Reyes was one of several members of the intellectual circle the ateneo de la Juventud who took an interest in Cuauhtémoc; others included the brothers Alfonso and Antonio Caso, and José Vasconcelos.

7 Ramón López Velarde, "Suave Patria", in La poesía mexicana del siglo XX, ed. Carlos Monsiváis, Mexico City, Empresas Editoriales, 1966, p. 278–283. [ Links ]

8 Carlos Pellicer, "Oda a Cuauhtémoc" (1924), in Carlos Pellicer, ed. David Martín del Campo, Mexico City, Cámara de Senadores de la República Mexicana, 1987, p. 79–80; [ Links ] Alfonso Teja Zabre, Historia y tragedia de Cuauhtémoc, Mexico City, Botas, 1929 [ Links ](issued separately in 1934 with preface by José Juan Tablada). Teja Zabre acknowledges his dependence on González Obregón's monograph of 1922.

9 To commemorate the 1910 Centenary of Mexican Independence, the Unión Cinematográfica produced the short film Torment of Cuauhtémoc, in which, according to the announcement, the scene was represented "with Mexican actors and in the location of the actual events".

10 The four–meters–tall statue, cast by Tiffany & Company of New York, was set at a busy crossroads in Rio de Janeiro where the Avenida Osvaldo Cruz meets Botafogo. Its granite pedestal was designed by Carlos Obregón Santacilia in an art deco style with pre–Hispanic elements. This versatile architect also designed the Mexican pavilion in a neo–colonial style.

11 Luis González Obregón, Cuauhtémoc, Mexico City, Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, 1922. [ Links ] In keeping with the government's diplomatic objectives, the book portrays Cuauhtémoc as a unifier of separate states and beneficent figure quite unlike his oppressive and hostile forebears. In 1927, when Pani was established as ambassador to France, he commissioned for the legation building a series of eighteen oil paintings from the Mexican painter Ángel Zárrraga. These represented the historical progress of Mexico, and the first in the series showed the Torture of Cuauhtémoc, symbolizing, according to the written program, "la energía y estoicismo de la raza india"; El anhelo por un mundo sin fronteras: Ángel Zárraga en la legación de México en París, Mexico City, Museo Nacional de Arte, 1990.

12 Alberto J. Pani, Apuntes autobiográficos, 2nd ed., Mexico City, Porrúa, 1950, v. 1, p. 312; [ Links ] the statue was made "con el fin de dejar en aquel gran país iberoamericano una constancia imperecedera de nuestro fraternal concurso en la conmemoración del acto más trascendental de su evolución política y capaz de memorar, al propio tiempo, el origen común de los pueblos que viven y crecen en la porción ibérica de este continente y las cualidades a que deben su autonomía". The gift of the statue to Brazil may have constituted a response to the erection of a Columbus Monument in Argentina in 1921, commissioned by the Italian government and sculpted by the Italian artist Arnaldo Zocchi.

13 President Obregón and secretary Pani imposed limits on Mexico's commitment to Latin–American unity, however, and stayed away from the Fifth Pan–American Conference, held in March 1923, at Santiago, Chile, in order to cultivate a diplomatic relationship with the United States, which formally recognized the regime later that year, according to the terms of the controversial Bucareli Agreement.

14 The oration was printed in the Brazilian Journal Livro de ouro, and published in Mexico by Julio Jiménez Rueda, "El discurso de Vasconcelos a Cuauhtémoc", in Bajo la Cruz del Sur, Mexico City, M. Manón, 1992, p. 112–121, [ Links ] later republished in Vasconcelos' Obras completas, Mexico City, Libreros Mexicanos Unidos, 1958, v.2. p. 848–853. [ Links ] See also his Memorias, 2. El desastre, el proconsulado, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1982, p. 131–132; [ Links ] and for an analysis, Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, "A tropical Cuauhtémoc: celebrating the Cosmic Race at Guanabara Bay", Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, 65, 1994, p. 117–121. [ Links ]

15 José Vasconcelos, La raza cósmica: misión de la raza iberoamericana, notas de viajes a la América del Sur, Paris, Agencia Mundial de Librería, 1925. [ Links ] Vasconcelos later wrote Breve historia de México (1936) and Hernán Cortés: creador de la nacionalidad (1941), in which he sided with conservative hispanism and condemned the Aztec past as a barbaric despotism. He described indigenismo as a debilitating philosophy which keeps Mexico weak and subservient to the United States. And while celebrating Cortés as bearer of peace and civilization, he dismissed Cuauhtémoc as an invention of William H. Prescott and other Anglo–Saxon historians.

16 With respect to his sense of historical progress, Vasconcelos may be linked with thinkers of the late Porfiriato, such as Vicente Riva Palacio, Francisco Bulnes, and Justo Sierra, as suggested by Agustín F. Basave Benítez, México mestizo: análisis del nacionalismo mexicano en torno a la mestizofilia de Andrés Molina Enríquez, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1992, p. 37. [ Links ]

17 In his speech at Rio, Vasconcelos spoke of the "new civilization" of the Spanish conquistadores, which "annihilated forever the proud conquered Mexican race"; Obras completas, Mexico City, Libreros Mexicanos Unidos, 1958, v. 2, p. 850.

18 For indigenismo in twentieth–century art, see Rita Eder, "Las imágenes de lo prehispánico y su significación en el debate del nacionalismo cultural", in El nacionalismo y el arte mexicano, IX Coloquio de Historia del Arte, Mexico City, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1986, p. 73–83. [ Links ]

19 An exception is a mural of c. 1925, painted by Vicente Mendiola on the façade of Cuauhtémoc School, which formerly stood on the corner of Costa Rica and República Dominicana streets in Mexico City. The institution was one of the Escuelas de Aire Libre established by the revolutionary government for the education of lower–class children. The painting (now destroyed) is said to have showed Cuauhtémoc with two other figures against a geometric background in the art nouveau style; María Luisa Mendiola, Vicente Mendiola: un hombre con espíritu del rinascimiento que vivió en el siglo XX , Mexico City, Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura 1993, p. 38. [ Links ]

20 A large compositional study for the mural, which is inscribed with the date August 13, 1929 (anniversary of the day Tenochtitlan fell), has been recently acquired by the Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City. It shows Cuauhtémoc with a war–club (macana) in his right hand, but in the final painting he wields a sling. The pose, headdress and armament of the Cuauhtémoc figure within the drawing are identical to those in an illustration of the fighting Emperor which Rivera made for the book Cuauhtémoc: tragedia, by Joaquín Méndez Rivas, Mexico City, 1925, p. 108–109 (Rivera drew a total of three images of the emperor for this publication, as well as several other designs). The pose was again employed for the figure of the emperor in the mural of the Battle for Tenochtitlan, Palace of Cortés, Cuernavaca. This series of frescoes also includes images of Cuauhtémoc's torture and execution, painted in grisaille.

21 Ida Rodríguez Prampolini, "Rivera's concept of history", in Diego Rivera: a retrospective, Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts, 1986, p. 131–138. [ Links ]

22 I do not share the interpretation of Leonard Folgarit, "Revolution as ritual: Diego Rivera's National Palace Mural", Oxford Art Journal, 14:1, 1991, p. 18–33, [ Links ] according to which the painting represents the march of history leading to the formation of the National Revolutionary Party (PNR). Nor am I persuaded by the suggestion of David Craven, Diego Rivera as epic modernist, New York, G. K. Hall, 1997, p. 110–124, [ Links ] that the mural approximates Brechtian theater.

23 Siqueiros' murals of Cuauhtémoc are Death to the invader, 1941–1942, Biblioteca Pedro Aguirre Cerla de la Escuela Mexicana, Chillán, Chile; Cuauhtémoc against the myth, 1944, Tecpan de Tlatelolco, Mexico City; and the diptych Cuauhtémoc Redivivus (a.k.a. Monument to Cuauhtémoc), 1950–1951, composed of Torment of Cuauhtémoc and Apotheosis of Cuauhtémoc, Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City. His easel paintings include Cuauhtémoc, 1940, Blanton Museum, University of Texas, Austin; Portrait of Cuauhtémoc, 1947, Nagoya City Art Museum, Japan; Emperor Cuauhtémoc, 1950, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City; and Homage to Cuauhtémoc, 1950, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City. Among the paintings that were made as studies for murals or derived from them are Agony of the Colonial Centaur, 1942, Collection Álvar Carrillo Gil, Mexico City; Malinche and Cortés, 1954, Collection Albert Mitchell, New York; and Centaur of the Conquest, 1944, collection Arturo Carrillo Grijalva, Mexico City, also developed into a lithograph of 1946.

24 The painting was originally installed in the private house of Siqueiros' mother–in–law, at 9 Avenida Sonora, Colonia Condesa. The Tecpan is where Cuauhtémoc supposedly resided after the arrival of the Spaniards. It is located near the Plaza de las Tres Culturas and the ruins of ancient Tlatelolco. Adjacent to the ruins is a large marker inscribed with the words of president Adolfo López Mateos, placing Cuauhtémoc's final defense within the context of mestizaje and the birth of the nation: "El 13 de agosto de 1521, defendida heroicamente por Cuauhtémoc, cayó Tlatelolco en manos de Cortés. No fue triunfo ni derrota, fue el doloroso nacimiento del pueblo mestizo que es el México de hoy".

25 The dramatic effect is further diminished by changes made to the composition in November 1964. Siqueiros and his team expanded the painting by inserting an additional panel through the middle of the pictorial field, so that Cuauhtémoc is more distant from his adversary, producing an image which is less congested but also less immediate and concussive.

26 Moctezuma is an important figure within the painting. He is, according to Siqueiros, the embodiment of the "mediocrity and political anemia", which is as pervasive in modern times as it was at the moment of the Conquest and which Siqueiros hoped to reverse with his arousing mural; José Navidad Rosales, "Entrevista con David Alfaro Siqueiros", Siempre!, probably 1963, typescript in the Archivo Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, Mexico City, folder 14.3.4.

27 One measure of Cuauhtémoc's popularity was the stamping of a five–peso coin in 1947, with his portrait on the obverse. This numismatic honor had been earlier conferred on the emperor, when in 1915 his image graced a five–peso banknote printed by the Constitutional Government. The 1947 coin was reissued over the following years, and thereafter Cuauhtémoc has been featured on several different paper bills. The government further recognized Cuauhtémoc, in 1945, by installing a large painted portrait by Carlos Tejeda in the Corredor of the Emperors at the National Palace. Also from this period was Héctor Pérez Martínez's Cuauhtémoc: vida y muerte de una cultura, Madrid, Uguina, 1944, [ Links ] a popular biography which became an influential text, and according to Wigberto Jiménez Moreno, the "Bible" for adherents of the Ixcateopan finds; discussed in Benjamin Keen, The Aztec image in western thought, New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 1971, p. 146, 543–546. [ Links ]

28 At a conference at Bellas Artes in 1947, Siqueiros criticized the "passivity" of all revolutionary and proletarian groups, including labor unions and the Communist Party; David Alfaro Siqueiros, typed notes for the lecture, "Proceso histórico de la pintura mexicana moderna", Archivo Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, folder 9.3.4.

29 Reported in Angélica Arenal de Siqueiros, "Cuauhtémoc contra el mito de David Alfaro Siqueiros", Excélsior, June 5, 1963. When Toledano participated in the mural's inauguration, June 7, 1944, he served as director of the Confederation of Latin American Workers (CTAL).

30 Quoted in Raquel Tibol, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Mexico City, Empresas Editoriales 1969, p. 290. [ Links ]

31 "Folklorism", abounds in classic films like María Candelaria, which appeared in 1943, a year before Siqueiros' mural, and it was perpetuated in the work of muralists and easel painters, most egregiously by Diego Rivera, whom Siqueiros rebuked in "Rivera's Counter–Revolutionary Road", The New Masses, May 1934, p. 16–17, 38 (published in Spanish as "El camino contrarrevolucionario del pintor Rivera", El Universal Ilustrado, 13, September 1934). Among other faults, he blamed Rivera for not outgrowing "folklorism", for not conducting experiments in new painting materials, and for political trotskyism. All three of these tendencies are rectified in Siqueiros' murals of Cuauhtémoc, which are pointedly anti–Riveresque.

32 David Alfaro Siqueiros, No hay más ruta que la nuestra: importancia nacional e internacional de la pintura mexicana moderna, Mexico City, Talleres Gráficos/Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1945, p. 72: [ Links ] "Las fuentes profundas de la tradición mexicana no están en los aspectos superficiales, en las expresiones pintorescas, en pueriles 'fórmulas de mexicanidad' […] [pero] están precisamente en la naturaleza monumental, superiormente monumental, específicamente ideológica, de las sorprendentes culturas prehispánicas y, también, aunque en menor proporción, dentro de lo saludable del arte mestizo colonial". Siqueiros' formulation of a new artistic canon in the 1940s coincided with the revaluation of pre–Hispanic art by scholars such as Justino Fernández, Manuel Gamio, Salvador Toscano, José Juan Tablada and George Kubler. He identified the expressive possibilities of elaborate surface treatments in an essay on his mural at Chillán, Chile, which features Cuauhtémoc; David Alfaro Siqueiros, "Un eco artístico embrionariamente transcendental en Chile", typed manuscript, Archivo Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, Mexico City, folder 11.1.105.

33 David Alfaro Siqueiros, "Propósitos esenciales del Centro de Arte Realista Moderno", in No hay más ruta que la nuestra: importancia nacional e internacional de la pintura mexicana moderna, Mexico City, Talleres Gráficos/Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1945, p. 80. [ Links ]

34 Ramón Berzunzu Pinto, Los indígenas y la República Mexicana: la política indigenista del Partido Comunista Mexicano, Mexico City, Cooperativa de Artes Gráficas Cuauhtémoc, 1941, p. 20; [ Links ] see also Andrés Medina, "Los pueblos indios en la trama de la nación: notas etnográficas", Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 60, 1998, p. 131–168. [ Links ]

35 Alexander S. Dawson, "From models for the nation to model citizens: indigenismo and the 'revindication' of the Mexican Indian, 1920–1940", Journal of Latin American Studies, 30, 1998, p. 279–308. [ Links ]

36 This trend may be traced through the speeches of Lombardo Toledano. In a lecture of 1940 at the Primer Congreso Indigenista Interamericano, Pátzcuaro, he argued that indigenous communities should be granted autonomy in land, government, language and culture; a decade later, during his presidential campaign, he proposed moving industry into rural areas to integrate indígenas into the proletariat; "Discurso pronunciado por Vicente Lombardo Toledano, delegado de México, respecto al problema fundamental del indio" (1940), in his El problema del indio, ed. Marcela Lombardo, Mexico City, Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1973, p. 127–135; [ Links ] and "Discurso de Vicente Lombardo Toledano, candidato del Partido Popular la Presidencia de la República, pronunciado en Ixcateopan, Guerrero, el domingo 13 de enero de 1952", in El problema del indio, p. 161–173. Narciso Bassols, the guiding figure in the Mexican Communist Party, believed that any customs and habits which stalled the economic capacities of indígenas should be eliminated, including forms of production linked with popular traditions; Obras, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, c. 1964,p. 165, quoted in Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán, "Introducción", to Vicente Lombardo Toledano, El problema del indio, ed. Marcela Lombardo, Mexico City, Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1973, p. 28.

37 The indigenist aspect of the symbol is supported by Renato González Mello, "El régimen visual y el fin de la Revolución", in Hacia otra historia del arte en México, 3: La fabricación del arte nacional a debate (1920–1950), ed. Esther Acevedo, Mexico City, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 2002, p. 294–298. [ Links ]

38 Andrés Molina Enríquez, La revolución agraria de México, 1910–1920, Mexico City, Porrúa 1986 (originally published 1932–1936). [ Links ]

39 Gamio's writings from the 1940s are collected in Consideraciones sobre el problema indígena, Mexico City, Instituto Indigenista Interamericano, 1966 (originally published 1948).

40 The discovery and controversy are detailed in several sources, including Moisés Mendoza, Rey y señor Cuauhtémoc, Mexico Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, 1951; [ Links ] Alejandra Moreno Toscano, Los hallazgos de Ichcateopan, 1495–1951, Mexico City, UNAM , 1980; [ Links ] Lyman L. Johnson, "Digging Cuauhtémoc", in Body politics: death, dismemberment, and memory in Latin America, ed. Lyman L. Johnson, Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 2004, p. 207–244; [ Links ] and Paul Gillingham, "The emperor of Ixcateopan: fraud, nationalism and memory in modern Mexico", Journal of Latin American Studies, 37, 2005, p. 561–584. [ Links ]

41 Leyva Mancilla supported the excavation from the beginning. It was he who set up a state commission and recruited Guzmán to oversee the excavation, and he later tried to suppress the negative report of the Marquina Commission.

42 Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, México profundo: una civilización negada, Mexico City, Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1987. In response to this surge of indigenist thought, Hispanists rose to defend the European inheritance; for example, José Fuentes Mares, México en la hispanidad: ensayo político sobre mi pueblo, Madrid, Instituto de Cultura Hispánica, 1949. Cuauhtémoc's value as a symbol of el pueblo mexicano confronting internal and external enemies is reflected in a passage from Moisés Mendoza, Rey y señor Cuauhtémoc: el hallazgo de Ixcateopan, Mexico City, Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, 1951, p. 11: "Cuauhtémoc es el ejido frente a la encomienda o al latifundio, y por eso lo aman los campesinos; es la protesta permanente contra toda injusticia, y por eso lo odian los injustos; es el patriotismo puro, y por eso lo detestan los mercaderes de la patriotería; es una voz de alerta para la integridad de la Patria, y por eso lo denigran los enemigos de México; es una actitud vertical frente al extranjero, y por eso lo menosprecian los serviles y lo enaltecen los patriotas."

43 Octavio Paz, The labyrinth of solitude, trans. Lysander Kemp, Yara Milos, and Rachel Phillips Belash, New York, Grove Press, 1985, p. 84. [ Links ] Paz discounts the Ixcateopan finds by stating that the tomb has not yet been located. See also his "Dos mitos", in El peregrino en su patria: historia y política de México, 1. Pasados, ed. Octavio Paz and Luis Mario Schneider, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1987, p. 96–100 [ Links ](originally published as a prologue to the 1951 French edition of Héctor Pérez Martínez, Cuauhtémoc: vida y muerte de una cultura).

44 The Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional interpreted a symphonic poem in tribute to Cuauhtémoc, and ballet pieces inspired by his life were performed at Bellas Artes in November 1949 and January 1950.

45 A history textbook by C. González Blackaller y L. Guevara, published in 1950 and authorized by the Secretary of Education, is dedicated to Cuauhtémoc, "símbolo de la soberanía nacional". Another approved schoolbook, from 1957, discusses Cuauhtémoc's bones and states that a group of scholars have convened to review the evidence, but omits any mention of the negative findings; Joaquín Jara Díaz and Elías Torres y Natterman, Historia gráfica de México para las escuelas primarias, Mexico City, 1957, p. 261, quoted and discussed in Josefina Vázquez de Knauth, Nacionalismo y educación en México, Mexico City, El Colegio de México, 1970, p. 240. Since the mid–1920s lessons had been given on Cuauhtémoc and other native heroes in an effort to endow Indian pupils with a greater sense of confidence and self worth. This initiative was redoubled in the 1930s and 1940s, especially following Samuel Ramos' 1934 diagnosis of the Mexican inferiority complex, and in 1942 the Secretary of Education issued popular biographies of Nezahualcóyotl, Xicoténcatl and Cuauhtémoc; Josefina Vázquez de Knauth, op. cit., p. 163, 214–216. The biography of Cuauhtémoc describes him as "el símbolo de la tierra, de la grandeza del espíritu, del verdadero patriotismo. Se alza grande y glorioso a través del tiempo, a pesar de su cautiverio, su tormento y su ignominiosa muerte".

46 Diego Rivera, quoted in La Prensa, October 21 and 28, 1949, and Excélsior, October 19, 1949; see also Diego Rivera, "Hernán Cortés: los bellos héroes son vencidos por rivales horrendos" (1957), in his Obras, 2. textos polémicos, 1950–1957, ed. Esther Acevedo, Leticia Torres Carmona, and Alicia Sánchez Mejorada, Mexico City, El Colegio Nacional, 1999, p. 662–664. After trying to reconstruct Cuauhtémoc's appearance through an artistic interpretation of his mortal remains, in 1952 Rivera and Guzmán attempted to recover the likeness of Hernán Cortés in the same manner.

47 Vicente Lombardo Toledano, "Discurso de Vicente Lombardo Toledano, candidato del Partido Popular a la Presidencia de la República, pronunciado en Ixcateopan, Guerrero, el domingo 13 de enero de 1952", in his El problema del indio, ed. Marcela Lombardo, Mexico City, Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1973, p. 175.

48 Manuel Gual Vidal installed the commission with a formal ceremony at which its members stood before the Cuauhtémoc Monument on Paseo de la Reforma and declared their admiration for the hero. Its report was published under the title "El hallazgo de Ichcateopan", Revista Mexicana de Studios Antropológicos, 11, 1951. On August 23, 1951, Gual Vidal accepted Siqueiros' diptych Cuauhtémoc redivivus at Palacio de Bellas Artes. The pair of paintings continued the artist's personal interest in the symbol, yet the choice of subject seems to have been instigated by the Ixcateopan discovery (perhaps Gual Vidal also had some role in its selection), and indeed the twin panels, especially Apotheosis of Cuauhtémoc, directly address the importance of the regained symbol for the Mexican people. Siqueiros never seems to have endorsed the Ixcateopan finds, however, and it is probable that he remained suspicious of the discoverers' pseudo–science, even as he propagated the Cuauhtémoc symbol through his art. Siqueiros and Guzmán must have known each other quite well —they both served as directors of the Comité Mexicano por la Paz— but her name is not found on the list of dignitaries who attended the inauguration of the Cuauhtémoc murals at Bellas Artes, perhaps because Siqueiros had distanced himself from the excavation.