Introduction

In this article we explore the acquisition of negation using data collected from children acquiring three Mayan languages. The acquisition of negation is of interest because its production in children’s language provides information on how children acquire linguistic features that are relatively rare in child directed speech. Contributing to the rarity of negation in the speech of adults and children is the asymmetry between the adult use of negation in sentences, e.g. ‘That does not fit.’ and children’s use of negation in response to adult utterances, e.g. ‘No!’ The frequency mismatch between the adult use of clausal negation ‘not’ and children’s use of discourse negation ‘no’ in English remains a challenge to acquisition theories of all types (Cameron-Faulkner, Lieven and Theakston, 2007; Drozd, 2002; Klima and Bellugi, 1966).

Negation has different structural realizations in the world’s languages. In most Mayan languages, for example, sentence negation occupies an initial position that is external to the rest of the sentence. The external negation markers attract second position clitics that otherwise appear after the main predicate (Pye, 2016). The Mayan language K’iche’ is an exception to this generalization in that sentence negation occupies a clause-internal position (after the predicate). Thus, Mayan languages mark a three-way distinction between discourse negation (‘no’) and the external/internal forms of clausal negation. Negation also interacts with discourse, aspect and modality marking in Mayan languages, and therefore shows how children’s acquisition of these contrasts interacts with their acquisition of negation. In this article we explore whether children find it easier to acquire the discourse and external forms of negation in Yucatec and Q’anjob’al relative the internal form of negation in K’iche’.

The acquisition of negation in K’iche’1

K’iche’ uses the circumfix ‘(na) … ta(j)’ to negate all lexical categories: nouns, pronouns, verbs, prepositions, adjectives, and adverbs (Mondloch, 1978).2 Clausal negation results when the circumfix is applied to verbal and nonverbal predicates. The examples in (1) illustrate clausal forms of negation in the Zunil variant of K’iche’.

The initial part of the circumfix is optional in the adult language, and is frequently omitted in speech to children. The final part of the K’iche’ circumfix appears as ‘taj’ in clause final contexts and as ‘ta’ in non-final contexts. We label the final part of the K’iche’ circumfix an irrealis marker since ‘ta(j)’ also marks irrealis in optative and conditional contexts. Romero (2012) proposes analyzing the post-predicate clitic ta(j) as the sole negation marker in K’iche’ as the initial negator na is frequently omitted.

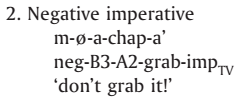

K’iche’ speakers have the option of substituting the negative aspect prefix m- for the circumfix in imperatives (2). K’iche’ marks aspect in non-negative imperatives with k-, ch- or ø- (Mondloch, 1981: 86-87). The negative imperative prefix is used in place of these aspect prefixes. The circumfix may also be used to negate imperatives.

K’iche’ distinguishes cases of existential negation from constituent negation (3). If children use constituent negation in existential contexts, we would expect K’iche’ children to use the circumfix to negate the constituent. In this case, the irrealis marker will follow the constituent (3a). If the children negate the existential verb rather than the constituent, the irrealis marker will follow the existential and precede the constituent (3b).

The Zunil variant of K’iche’ has borrowed the negation marker ‘no’ from Spanish for discourse negation (4). Thus, K’iche’ makes a distinction between discourse and clausal negation. K’iche’ does not make a distinction between clausal and constituent negation. Cases where K’iche’ children extend the discourse form to clausal contexts of negation will be immediately obvious.

K’iche’ input

The K’iche’ data were recorded by the first author in Zunil, Guatemala (Pye, 1992). We analyzed the forms of negation in three hour-long samples of K’iche’ input to establish the frequency of the different negation markers in speech directed to K’iche’ children. We analyzed three recordings of a K’iche’ mother speaking to the child TIY (2;0) and her sister in their home. The negative forms the mother produced and their frequency are shown in Table 1. The input data show that K’iche’ children are exposed to a variety of negation forms, albeit with low frequencies of use.

Table 1 shows that negation only occurred in 5 to 9 percent of the mother’s speech. The circumfix form of negation constituted 81 percent of the negation markers that TIY’s mother produced. Only 6 percent of her negative markers were the discourse forms no and nik. Table 1 shows that TIY’s mother omitted the initial part (na) of the circumfix in 25 utterances and produced the full circumfix in 17 utterances. She used the negative imperative prefix m- in 4 utterances.

The example in (5) shows the mother’s omission of the first part of the circumfix in a context of clausal negation.

K’iche’ acquisition

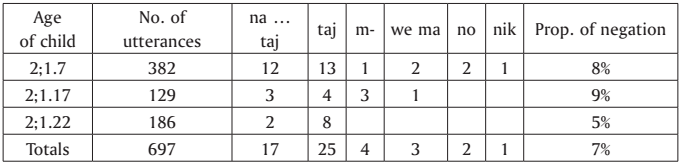

The K’iche’ acquisition data were derived from three hours of recordings with the two-year-old girl TIY (Pye, 1992). The forms and frequency of negative marker frequencies in K’iche’ child speech are shown in Table 2.

While TIY produced the same overall proportion of negative utterances as her mother, her forms of negation differ from her mother’s forms in two significant respects. TIY always omitted the initial part of the circumfix and relied exclusively on the final part of the circumfix to negate clauses. Discourse negation constituted 67 percent of TIY’s negation production in comparison to only 6 percent of her mother’s negation marking. There is no evidence that TIY substituted the discourse form ‘no’ in clausal contexts of negation.

The differences in the frequency of production in TIY’s speech and in that of her mother show that TIY is not simply imitating the forms she hears in the input. TIY is negotiating a different discourse than her mother. While her mother attempted to get TIY to talk, TIY used discourse negation to refuse her mother’s entreaties. We provide examples of TIY’s negation forms in (6).

These examples show that TIY uses ‘no’ for discourse negation and the internal negation marker ‘ta(j)’ for clausal negation. The negative imperative example (6c) shows that she does not yet use the prefix form for imperative negation (m-). This form is optional in the adult grammar, but children consistently use ‘ta(j)’ for all forms of clausal negation. At first, K’iche’ children only use the second part of the negative circumfix, and only start producing the initial part when they are over three years old (id.).

The example in (6c) is also interesting because TIY used ‘ta(j)’ in the initial position of the utterance as well as after the verb. There is the possibility that TIY used the utterance-initial ‘ta(j)’ as a form of discourse negation rather than the result of verbal ellipsis. If so, TIY would be extending an internal form of clausal negation to discourse contexts. We do not have consistent evidence from K’iche’ children that would strongly support this hypothesis, but we do have the example in (7) that is consistent with this idea. In this discourse context TIY responds to her brother’s command with ‘ta(j)’ rather than with ‘no’. This example is also ambiguous since TIY may not have intended her utterance to be a response, but rather an observation. If we interpret her utterance as a response, then it shows the use of ‘ta(j)’ as a marker of discourse negation.

The results show that TIY demonstrates an early distinction between discourse and internal clausal negation. There are no instances in which K’iche’ children substitute the discourse form ‘no’ in a context of clausal negation. While there are some examples that might be interpreted as extensions of the clausal form to discourse contexts, these are ambiguous. K’iche’ children systematically omit the external negation marker ‘na’. The K’iche’ results suggest that children acquiring Mayan languages cannot access negation markers in the external position.

The acquisition of negation in Yucatec

Yucatec, like K’iche’, has a fairly simple form of negation as shown in Table 3. Yucatec uses the form ‘ma’’ to mark both discourse and clausal negation3. Unlike K’iche’, clausal negation has an external position preceding the predicate in Yucatec.

The example sentence in (8) shows that discourse negation can combine with and precede clausal negation in a sentence. This example also illustrates the use of the ‘trapping’ particle -i’ at the end of the clause. This particle occurs at the end of the clause rather than following the verb complex as in K’iche’. Durbin & Ojeda (1978: 60) state that the trapping particle marks the end of a constituent that is focused by a question, locative, demonstrative or negation. Its use is optional.

Although the forms of negation are fairly restricted in Yucatec, there are complications. Yucatec does not use the clausal negation form ‘ma’’ with verbs in the incompletive aspect (9a). The continuous form of the verb is used instead to express the negation of habitual events (9b). The negation of a continuous event requires the addition of the trapping particle -i’ (9c) (Durbin & Ojeda, ibid., 54-55).

Yucatec also has other forms of clausal negation. The form ‘mix’ is primarily used to negate nominal, pronominal and adjectival predicates with translations of “no” or “neither” (Bolles & Bolles, 2014). The eastern dialect of Yucatec studied here uses the form ‘mix’ (10) as well as ‘ma’’ for clausal negation. All variants of Yucatec use the form ‘min’ for existential negation (11). Yucatec also uses the form ‘bik’ in preventative contexts (12). The trapping particle -i’ is not used with either ‘min’ or ‘bik’.

Children learning Yucatec must learn to use the form ‘ma’’ in both discourse and clausal contexts of negation. They will still need to distinguish between the discourse and clausal contexts since the trapping particle -i’ is only used for clausal negation. They will need to learn that clausal negation is not used with verbs in the incompletive aspect. They will also need to limit their use of the variant form ‘mix’ to clausal contexts. Finally, Yucatec children must learn the contexts of use for the forms ‘min’ and ‘bik’.

Yucatec input

The Yucatec data are derived from recordings made by Pfeiler in the town of Yalcobá in the eastern part of the state of Yucatán, Mexico (Pfeiler, 2003). The recordings were made two times a week with 3 children. For this study we selected the audio-recordings of the child ARM who was often recorded in the presence of his cousin, SAN, who was one year older than ARM. Because of the different ages the caretakers of both children (mothers, aunts and grandmother) interacted more with SAN than with ARM. This explains the low frequency of utterances in ARM’s mother’s speech. In this study we analyzed the negative forms that ARM’s mother and investigator (a Mayan native speaker) produced in the child’s language samples to obtain a picture of negation in the adult input. These results are shown in Table 4.

ARM’s caretakers produced negative utterances more frequently than the K’iche’ mother. They produced a form of clausal negation in 34 of their 37 uses of negation (92 percent). They only produced three tokens of ‘ma’’ as discourse negation (8 percent). The adults produced the preventative marker ‘bik’ 6 times or 19% of the negative forms in this sample. ARM’s caretakers produced the -i’ suffix in 7 sentences, with both negation markers, ma’ and mix. An example is shown in (13a). The sentence in (13a) demonstrates the omission of the incompletive aspect marker in the context of negation. The verb in this sentence has the dependent suffix ‘-uk’. Other productions with ‘ma’’ and ‘mix’ included deictic particles in place of the -i’ suffix (13b). The adults’ productions show that ‘ma’’ is the most frequent negative form in the samples.

The examples in (14) illustrate the mother’s use of ‘ma’’ for verbal and nonverbal predicate negation. In (14a) the negative marker appears with an imperative verb. The trapping particle is used when negating the nominal predicate in (14b).

On the basis of this input data we might expect children acquiring Yucatec to use the most frequent markers ‘ma’’ and ‘bik’ for negation. The use of the trapping particle -i’ is optional, it serves other functions such as a focus particle for locative phrases and it appears at the end of a negative clause. Only with the verbs ‘to want’ (k’at and óot) it is mandatory as long as the verb is in final position of the sentence (Bolles & Bolles, op. cit.).

Yucatec acquisition

The analysis presented here is based on data from five recordings for a two-year-old boy ARM (Armando). In these recordings ARM interacts with his mother, two aunts and his cousin Sandi. ARM’s use of negation is shown in Table 5.

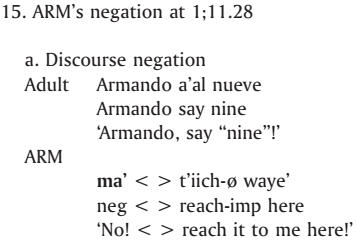

ARM’s general frequency of negative production is similar to that of his caretakers’. We found three differences with his caretakers’ forms of negation. In contrast to his caretakers ARM used ‘ma’’ more frequently as discourse negation (43%) than as clausal negation (11%). ARM also produced the trapping particle -i without ‘ma’’. Finally, ARM did not produce the preventative negation form ‘bik’. Examples of ARM’s use of ‘ma’’ in both discourse and clausal contexts are shown in (15). Note the use of the negative particle in the example (15b).

ARM produced the verbal root ‘óot’ with the -i’ suffix in the same session with the meaning of ‘I don’t want (it)’ (16). This is the only case where we could assume that Yucatec children follow the K’iche’ preference for post-predicate negation marking.

In negative existential contexts (17) ARM uses the form ‘na’an’ (= min + yan), in comparison with the affirmative contexts where the child uses ‘yan’. There is no evidence that he extended this form to discourse contexts of negation or that he extended the form ‘ma’’ to existential contexts.

ARM also produced an instance of ‘ma’’ in final position (18).

The Yucatec data for negation are significant because they show that Mayan children use the same form of negation (ma’) in both discourse and clausal contexts if the adult language does. This use is similar to that in Spanish and child English, and contrasts with the distinctive forms of discourse and clausal negation in K’iche’. Like the K’iche’ child, ARM used negation more frequently in discourse contexts than his caretakers. ARM marked the distinction between clausal and existential negation appropriately by two years of age. We also note that the Yucatec child differed from the K’iche’ child in his use of the clause initial markers of clausal negation. Unlike the K’iche’ child, ARM displays an early use of the external form ‘ma’’. The Yucatec evidence shows that the use of preverbal negation markers is accessible to two-year-old children. The syntactic position of the preverbal negation marker does not explain the K’iche’ child’s omission of ‘ma’.

The data suggest that ARM has a basic understanding of the contexts in which the trapping particle -i’ is used. He did not use the trapping particle with ‘min’. This is remarkable since the trapping particle occurs at the end of the clause rather than as a verbal circumfix. ARM produced 7 tokens with one verb that follow the K’iche’ preference of using a post-predicate negation marker.

The acquisition of negation in Q’anjob’al

Q’anjob’al has contrasting markers for discourse negation as well as for clausal negation and the negation of focus phrases. We will not describe the full system of negation in Q’anjob’al in this paper since Q’anjob’al children only produce a subset of these negative markers. A description of Q’anjob’al negation in the adult grammar can be found in Mateo Toledo (2008).

The contexts of negation that feature in children’s speech have contrasts between different forms of discourse and clausal negation. The forms for clausal negation display a complex interaction between the negative markers and aspect as well as between the negative markers and the existential verb. This interaction provides evidence for the external structural position of negation in Q’anjob’al.

The examples in (18) demonstrate the interaction between negation and aspect in Q’anjob’al. The negative marker ‘maj’ is restricted to verbs in the completive aspect (18a). Like the K’iche’ negative imperative prefix m-, ‘maj’ appears in place of the completive aspect marker ‘max’. The use of ‘maj’ also requires a change to the dependent status suffix -oq. The negative marker ‘k’am’ is used with verbs in the incompletive aspect (18b). It selects for a fully inflected verb complement that has the incompletive aspectual prefix ch- as well as the indicative status suffix -i. Q’anjob’al uses the marker ‘man’ with verbs in the potential aspect (18c). ‘Man’ also negates imperative verbs. In addition, Q’anjob’al uses the negative marker ‘toq’ for verbs in all three indicative aspects (18d).

The negative markers ‘toq’ and ‘k’am’ display an interesting interaction with the existential in Q’anjob’al (19). ‘Toq’ is used with the existential (19a) while ‘k’am’ is used in place of the existential (19b). The sentences have very similar meanings.

The contrasting forms of discourse negation that appear in the Q’anjob’al recordings are ‘maj’, ‘manchaq’ and ‘k’amaq’. ‘Maj’ and ‘manchaq’ are used in response to commands while ‘k’amaq’ is used in response to ‘yes/no’ questions. Q’anjob’al also has the negative imperative marker ‘man’ and a marker for preventative negation ‘ta’. ‘Ta’ is the only negation marker in Q’anjob’al that occurs after the verb, much like the K’iche’ irrealis marker ‘ta’.

Q’anjob’al input

Mateo Pedro (2015) recorded the Q’anjob’al girl, XHUW, between the ages of 1;9 and 2;3 living in Santa Eulalia, Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Table 6 provides the frequencies for the negative markers in a one-hour sample of the speech of XHUW’s father.

In this recording, XHUW’s father directs most of his speech to XHUW, but also interacts with his wife. Only about 5 percent of his utterances contained negation. XHUW’s father produced a large number of preventative imperatives as well as clausal negation with incompletive verbs. Q’anjob’al input is similar to the samples of K’iche’ and Yucatec input in that the frequency of clausal negation (96%) is much higher than the frequency of discourse negation (4%).

Q’anjob’al acquisition

We analyzed twelve recordings for XHUW that were each approximately one hour in duration. Q’anjob’al children produce a variety of negation forms by two years of age. XHUW produced an early contrast between the forms ‘maj’ and ‘k’am’, and there is also evidence that she employed ‘toq’ as well. While XHUW produces a variety of negation forms, there is also evidence that she was learning their selectional restrictions.

The initial forms of XHUW’s negation markers are very similar. The examples in (20) show her initial productions for ‘maj’ and ‘k’am’ in contexts of clausal negation. Both words were reduced to /a/ with a following glide or a preceding glottal stop. The transcribers relied upon the discourse context to interpret XHUW’s intended target form. At this age, XHUW regularly replaced /k’/ with a glottal stop. The omission of initial /m/ was less regular.

The examples in (21) show XHUW’s forms of existential negation. XHUW seems to have already mastered the use of the existential with ‘k’am’ and ‘toq’. She omits the existential correctly with ‘k’am’ in (21a) and produced the existential with ‘toq’ in (21b). These examples suggest that Q’anjob’al children acquire the constraint on the use of the existential in contexts of negation quite early.

We provide examples of XHUW’s forms of discourse negation in (22). The exchange in (22a) shows the early use of ‘maj’ as a marker of discourse negation. The exchange in (22b) shows a form that was interpreted as a context for the use of ‘k’amaq’, but in which XHUW produced ‘maaj’. Since we lack evidence that vowel length was contrastive for XHUW, we interpret this exchange as a case where XHUW extended ‘maj’ to a yes/no question context where ‘k’amaq’ is obligatory.

The error in (23) is interesting since it provides evidence that XHUW had to learn the constraints on verb inflection in the context of negation. Here, XHUW combines the negative marker ‘maj’ with a verb that has the incompletive aspect marker ch-. Another possibility is that XHUW used the discourse negation marker ‘maj’ in a context of clausal negation. This extension would explain why XHUW appears to violate the constraint on the use of the clausal form ‘maj’ with the aspect marker.

Finally, we observed an interesting case in which XHUW incorrectly places the negation marker ‘maj’ in final position rather than in initial position (24). This is another case in which XHUW has potentially extended the discourse negation form ‘maj’ to a context of clausal negation. In this case, a clausal negation marker should precede the verb ‘kachi’ as indicated by the English gloss. Her use of ‘maj’ after the verb ‘kachi’ is evidence that XHUW is using the discourse negation marker ‘maj’ as a form of clausal negation This example resembles the K’iche’ child’s use of ‘ta(j)’ in the initial position c), and suggests that Mayan children are open to the possibility of marking negation in either clause-initial or clause-final position.

We present a summary of XHUW’s correct and incorrect negative markers in Table 7. This table shows that two sessions were recorded at each age; so separate numbers of utterances in each session are given. XHUW had a lower frequency of negation use than the K’iche’ and Yucatec children. Table 7 shows that while XHUW maintained a contrast between ‘maj’ and ‘k’am’ in contexts of clausal negation, she failed to observe the constraint on the production of ‘maj’ in the absence of overt aspect marking. She extended ‘maj’ to incompletive aspectual contexts as well as using it with the incompletive prefix in completive contexts. The data indicate that XHUW extended the discourse negation marker ‘maj’ to contexts of clausal negation in which the aspect marker is not used.

Notation: ‘maj > k’am *1’ indicates ‘maj’ was incorrectly substituted for ‘k’am’ one time. ‘maj ..-oq 1’ indicates that ‘maj’ was used once with a verb that had the suffix ‘-oq’ while ‘maj 2; *ch 1’ indicates ‘maj’ was used twice and one of those uses incorrectly with a verb that had the incompletive prefix ‘ch-’.

In the contexts of discourse negation, XHUW systematically replaced ‘k’amaq’ with ‘maj’. While this replacement indicates that XHUW treats both words as forms of discourse negation, she had not acquired an understanding of the ‘yes/no’ contexts for use for ‘k’amaq’. We conclude that XHUW had an incomplete understanding of the use of discourse negation, and in this respect resembles the Yucatec child’s grammar of negation marking rather than the K’iche’ child’s grammar.

Conclusion

We have presented data on the acquisition of negation in three Mayan languages -K’iche’, Yucatec and Q’anjob’al. All three languages have a common structure for negation. Discourse negation occurs in a preclausal position. Clausal negation is marked in an external, pre-predicate position. K’iche’ added the negation marker ‘ta(j)’ in a post-predicate clause internal position, while Yucatec added the trapping particle ‘-i’ in a clause-final position. At the same time, all three Mayan languages require children to learn how negation interacts with other grammatical features that differ from language to language. The three languages have developed aspectual and modal contrasts with negation. Q’anjob’al and Yucatec preserved distinct forms for negation in existential contexts, while K’iche’ extended its clausal form of negation to the existential context (Pye, 2016).

The acquisition data that we present for Mayan negation show children engaging in a variety of language specific acquisition patterns. The K’iche’ child consistently used the clause internal negation marker ‘ta(j)’, whereas the Yucatec and Q’anjob’al children used clause external negation markers. The Yucatec child demonstrated a knowledge of the contexts of use for the trapping particle -i’. The Q’anjob’al data provides evidence of the extension of the discourse negation marker ‘maj’ to contexts of clausal negation. The K’iche’ child did not use the discourse negation marker in clausal negation, unlike the Yucatec and Q’anjob’al children. These data show that two-year-old Mayan children engage with a common negation structure in a variety of language specific manners.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)