Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Estudios de cultura maya

versión impresa ISSN 0185-2574

Estud. cult. maya vol.38 Ciudad de México ene. 2011

Artículos

Politics in the Western Maya Region (I): Ajawil/Ajawlel and Ch'e'n*

Péter Bíró

Abteilung fiir Altamerikanistik, Universitat Bonn. bpetr30@gmail.com

Recepción: 15 de septiembre del 2010.

Aceptación: 22 de febrero del 2011.

Resumen

En una serie de artículos como éste investigo el uso de varias palabras en las inscripciones mayas de la época Clásica de la Región Occidental vinculadas con lo que nosotros llamamos "política". Estas palabras expresan conceptos que ayudan a entender los matices de las relaciones entre las entidades políticas de las Tierras Bajas Mayas y su organización interna. Términos como ajaw'ü I ajawlel, los difrasismos con base ch'e'n (cueva, pozo), los glifos emblemas y los títulos serán examinados tomando en cuenta la información que nos proporcionan sobre el funcionamiento de la organización política de la época Clásica en una región restringida.

Palabras clave: Maya Clásico, epigrafía, vocabulario político, títulos.

Abstract

In a series of articles I reflect on the use of various expressions which are connected to what we call the political in the inscriptions of the Classic Maya Western Region. These words express concepts which help to understand the intricate details of the interactions between the political entities and their internal organisations in the Classic Maya Lowlands. Words such as 7ajawil, 7ajawlel, the kennings built on the base of ch'e7n (cave, pond), the emblem glyphs and titles will be examined in light of what they tell us about the functioning of the political organisation of the Classic Period in a constrained region.

Key words: Classic Maya, epigraphy, political vocabulary, titles.

In this paper I investigate Classic Maya (AD 300-900) politics using my own and others' investigations based on inscriptions mostly coming from the Western Maya Region.1 It is known that it was an elite group who commissioned these inscriptions, consisting of rulers and their close family, and also of a group of high status individuals bearing distinctive titles. As many scholars noted, the main task of this group was the political integration of Classic Maya society, therefore it is likely to expect that their own memories carved in rock have evidence about politics. Mayanists are also aware of the conspicuous presence of a single figure in Classic Period politics, the k'uhul ajaw2 or 'divine lord' that was the focal point of a court society regulating the affairs of the polity, itself forming an institution (Freidel and Schele, 1988; Houston and Stuart, 1996, 2001; Miller and Martin, 2004).

One way to understand this institution is to separate its many connections and components, and to analyse the words which were used to represent it in inscriptions. The emic conceptualisation3 of this institution may help for current researchers to understand better Classic Maya politics. In the followings I undertake an investigation of the political vocabulary of Classic Maya inscriptions in order to reconstruct such an emic conceptualisation of some aspects of Classic Maya politics.4

On Political Vocabulary

The investigation of political vocabularies is undertaken within several theoretical frameworks (Richter, 1986, 1987; Schmidt, 1999; Skinner, 2002; Koselleck, 2003). It is assumed that in human cultures there is a set of conceptualisations describing the relationship of social actors and the organisation of their respective actions. This set of concepts can be expressed by simple lexemes, however not all concepts equates a word and vice versa. As Quentin Skinner (2002: 159) eloquently noted that while for Milton to be a poet was certainly conceptualised to have originality, the latter word "did not enter the language after a century or more after his [Milton's] death".

Therefore, in the theory of Skinner, word and concept are two distinct phenomena which should be taken into account by epigraphers looking for ancient minds behind the Classic Maya narratives.5 This differentiation of concepts and words is crucial in the examination of Classic Maya elite political vocabulary which was in turn expressed by words. Also, words as such have criteria of use, reference and they are connected to underlying attitudes. The connection of political vocabulary and politics according to Skinner (2002: 174) is a mutual interdependence where political vocabulary is a constraint on political action, the classification of phenomenon is not inherent in nature but in the human mind, and once the classification happened, language can be a difficult tool to be changed as one wishes it.

Slightly different, but equally perceptive insights can be drawn from the German school of 'conceptual history' (see Koselleck 2003 for application). Just as in the history of ideas they make a distinction between words and concepts, and they maintain that every concept is represented by a word, but not every word carries a concept within itself (Koselleck, 2003: 134). Koselleck (2003: 134) noted that political concepts generalise and have multiple meanings. Therefore those words which express such concepts have multiple or overlapping meanings in the sense of reference involving layers of meanings. An example is cited by Koselleck (2003: 135) in the conceptualisation of the 'state' which absorbed other concepts such as "authority, sovereignty, territory, law, taxation, citizenship, army etc.". The changes of the 'state' concept can be investigated not only by the use of the word 'state' but also by the investigation of the changing alignments of the concepts absorbed into it or into its semantic field: a "relatively unified part of a language's vocabulary at a given time" (Richter, 1986: 625).6

Such an investigation about Classic Maya political vocabulary is difficult to undertake as at present there are problems to interpret words and their political reference, or to find a meaningful way to reach the conceptualisation of the Classic Period elite. An important obstacle is the lack of dictionaries and more personal reflections by the elite themselves which could have helped to disentangle multiple meanings and possible changes within semantic fields. Simply put, Maya epigraphers first have to deal with the enormous task to select of Classic Period political vocabulary, and examine the words' multiple references and find the best way to conceptualise them.

Both Skinner (2002: 175-184) and Koselleck (2003: 121-145) argued persuasively that actual words and their use—or their correspondence to concepts and changes within conceptual usage—reflect in various ways the social conditions in which the given language is embedded. Social and political conflicts can be examined by the use of words and concepts. As Koselleck (2003: 132-133) has pointed out there are at least three different classes of 'political concepts': first those ones which are relatively stable and used without much change; second, those which changed drastically in content though they are referred to by similar words; and third, those ones which are totally new and use new words also (neologisms). These changes can reflect various social tranformations, especially in the case of neologisms, or when major terms are re-analysed and put into use in very different contexts than before.

In the following I try to answer similar questions, or investigating the reference of various words which in turn formed part of the attested political vocabulary of the Classic Period elite. I hope to arrive at a better conceptualisation of these words. While I do not examine all of the political vocabulary, I suggest that some of the words and concepts changed during the 600 years of the Classic Period reflecting some social change.

The political vocabulary here chosen consists of the words ajawil/ajawlel and ch'e'n and its varieties in the inscriptions. My hope is that by the analysis of these words it is possible to gain a more nuanced understanding of Classic Maya politics in general (in one particular region), and political organisation in particular. In two following articles I intend to investigate the emblem glyphs and the titles of Classic Maya inscriptions as referrents to political practices.

ajawil/ajawlel

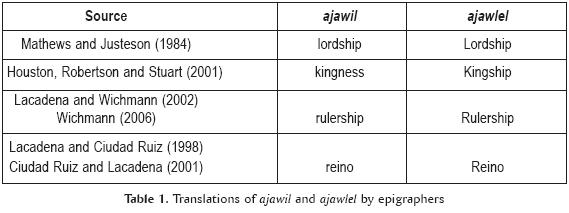

One of the most frequently mentioned words connected to politics are the derived nouns ajawil and ajawlel. However, their morphology, translation and reference are debated. In the following I list the different positions and ideas, and later I present my understanding of these terms. For lack of space I am not able to make a thorough analysis, rather I would like to point out some problems in previous interpretations and suggest an alternative solution.

Peter Mathews and John Justeson (1984) made the first thorough description and analysis of both words. Their analysis is sometimes neglected; but it has insights that will help to resolve many of the contentious issues surrounding the interpretation of ajawil/ajawlel. In their distributional analysis they arrived at the conclusion that all 'substitutions set B' was suffixed with -el, save the then recently deciphered cahal (sic) title which invariably was suffixed by T24/-Í1 (Mathews and Justeson, 1984: 224). Further on, in a very dense linguistic analysis they concluded that accessions were to the lordship (office) and not as lord (rank).7

Victoria Bricker (1986) demonstrated that the reading of the T168-188-188 collocation had to be ajawlel, which was confirmed by the analysis of the diacritical marks called 'syllabic sign-doublers' in the same collocation by Marc Zender (1999: 107-110).

Stephen Houston, John Robertson and David Stuart (2001: 22) noted the existence of two forms as ajawil and ajawlel and categorised them as unpossessed abstractive nouns. Their conclusion, however, was differed from that of Mathews and Justeson (1984) as they suggested a different semantic meaning for ajawlel.

When used with titles, they seem to communicate the meaning of "-ness" in English, a concept abstracted from a concrete noun and generalized into a quality. In the main, the most frequent examples in the inscriptions refer to king-ness, as in AJAW-IL...or AK'AB'-IL..."darkness"...K'IN-ni/chi-IL..."intensely sunlike (place)"... In our view, there is a semantic distinction between these forms and those using the "institutional" -el attested in Ch'olti': by common understanding this form clusters toward the western half of the Maya Lowlands and seems also to be later. It can occur with or without the preceding -il. In itself, -el corresponds roughly to the English morpheme, "-ship", as in "kingship". This is probably the best translation of the well-known phrase ajaw-l-el, in which the first / is the abstractive and the second is the "institutional" marker. Interestingly, the two endings, -l-el, occur only on two status terms, ajaw-l-el and bach'ok-l-el, but never on sajal and other titles. To speculate, we might suggest that these statuses exhibit a further distinction: they are singular rather than multiple, particularly in the case of the "holy lord" and "first youth", of which there can be only one (Houston, Robertson and Stuart, 2001: 22-23).

In turn, this pattern was taken up by Alfonso Lacadena and Søren Wichmann (2002) who interpreted it as a reflection of Eastern and Western Ch'olan geographic markers, while they accepted the morphological analysis suggested by Houston, Robertson and Stuart (2001). They demonstrate that the distribution of ajawlel is wider than ajawil, but the latter is the earlier form. Also, they argued that ajawlel became a prestigious form to be used because of the wide-ranging influence of Calakmul (Lacadena and Wichmann, 2002: 25). They also indicated that the addition of the suffix -el to a proto-Ch'olan *ajaw-il was a Western Ch'olan innovation, but it is not possible to say whether the suffix changed the meaning or semantic field of the abstract noun. Indeed, they mentioned that their interest "is not the two suffixes as such, but the specific occurrence in the term for 'rulership'" (Lacadena and Wichmann, 2002: 16), implying to me that they do not suggest an actually different semantic field.

Søren Wichmann (2006: 281, table 1) confirmed this in his recent publication listing ajawil and ajawlel as contrastive pairs indicating "strong Eastern versus Western Ch'olan features" in the inscriptions. The translation given to both is 'rulership', or a similar semantic field, differing from the idea of Stephen Houston, John Robertson and David Stuart (2001).

Alfonso Lacadena and Andrés Ciudad Ruiz (1998; Ciudad Ruiz and Lacadena, 2001), argued that ajawil/ajawlel referred to 'kingdom' and was the basic component of hegemonic rule both in the Classic and the Postclassic Periods.

La entidad política gobernada por un ajaw, "rey, señor", es el ajawlel o ajawil en términos cholanos o el ajawlil en yucateco, los cuales fueron utilizados desde el Clásico hasta finales del siglo xvii (Lacadena y Ciudad, 1998), indicando de nuevo la continuidad en la concepción y en la estructura interna y externa del gobierno en las Tierras Bajas mayas desde su fundación hasta los diferentes procesos de colonización de la región. El manuscrito chontal deja claro en varias ocasiones que la fórmula de acceso a este territorio es chumvanix ta ajawlel "se asentó en el reino", "comenzó a gobernar", designándolo como toda la entidad política (Smailus, 1975: 32, apud Ciudad Ruiz and Lacadena, 2001: 27).

They perceive that ajawil/ajawlel refers to 'territory', and they translated the term in the accession sentence as 'kingdom'. According to this interpretation there is a single term for the political entity of the Classic Period: ajawil/ajawlel which depends on the particular linguistic area. They explicitly mention that there was continuity in the conceptualisation of political organisation from Classic to Post-classic.

Contrary to this suggestion, Stephen Houston (2000: 173; Houston, et ah, 2003: 215) asserted that there was not a single term referring to kingdoms or polities in Classic Maya inscriptions.

Terms for "kingdoms" or polities continue to be elusive...(Houston, 2000: 173)

At present there is not a single, attested term in Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions for cities per se or for the polities that heavily concern Mayanists (Houston et al., 2003:315).

It is important to point out the existence of linguistic evidence for the differentiation of the -VI and -el suffixes which leads me to the conclusion that the denotations of the two lexemes were originally different and they may not be synonymous. David Mora-Marín (2005: 20) argued for the existence of-Vl-el suffix in Proto-Ch'olan and Proto-Ch'olan-Tzeltalan:

These entries show the root ik' 'air' (Proto-Ch'olan *ik') and derived forms like ik'-ar 'wind' and ik'-ar-er 'vertigo'...Innovated *-(V)l-el and ancestral *-il (see above) were likely in coexistence given that modern Ch'olan languages exhibit such coexistence, as the following example of Ch'orti7 shows...(Wisdom, 1950: 702): chich 'soft bone, hard flesh, cartilage, muscle, gristle, tendon, vein or artery, grain (in wood), tough herb or stalk, though latex (rubber)', chichar 'muscle, mass of cartilage, chi-charir 'pertaining to muscles' (David Mora-Marín, 2005: 20).

The two examples from Ch'orti' cited by Mora-Marín confirm the analysis of John Robertson (in Houston, Robertson, and Stuart, 2001) and support the claim that the two terms are not dialectal features but have subtle differences in their denotations: ajawil is *king-ness and ajawlel is *kingship.

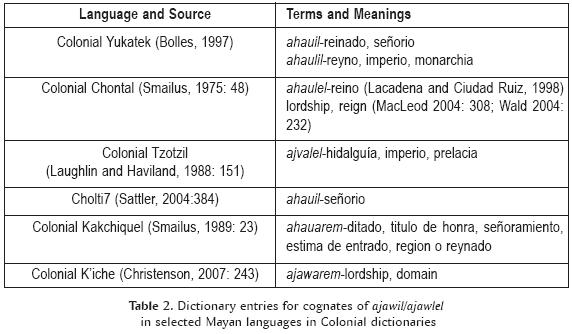

Colonial dictionaries concur that the primary meaning of the -VI derived forms of ajaw is 'kingship, lordship' referring to the office of a titled individual; but there is a secondary semantic field which refers to the territory under the authority of the person connected to this particular office (table 2). Those authors who argued ajawlel being a reference for territory based their translations on the use of linguistically cognate forms in Mayan languages in Colonial Sources recorded at least 600 years later than the Classic Period.

The basic question is, however, whether Late Postclassic and Colonial conceptualisations were similar to the conceptualisation of ajawil and ajawlel in the Classic Period. Or, whether there was a semantic shift which resulted in widened semantic fields of ajawil and ajawlel by incorporating the connotation of territory from the Classic to the Postclassic Periods.

To answer these questions it is indispensable to examine the linguistic contexts of these suffixes and lexemes in Classic Period inscriptions. Such an analysis may not give us a secure answer about all connotations of these words; however, it will give the pragmatic contexts of these lexemes and also their semantic environments. The investigations of these specific contexts may indicate some of the wider meanings of these terms.

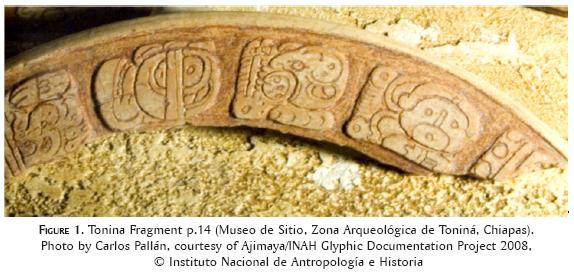

While Stephen Houston, John Robertson and David Stuart (2001: 22) found the -Vl-el suffix on the nouns of ajawil and bah ch'okil this is equally attested on sajal and kalomte' (figure 1).8 Three more titles are attested with the suffix - il in the inscriptions, all of them in accession statements: aj k'uhun, ti'sak hun, yajaw k'a[h]k' and nun (Zender, 2004: 157-159).

Although this affixation pattern can be interpreted as a dialectal/vernacular difference, I think that the temporal data warrant another interpretation. While it is clear that the earliest forms are attested with -li all over the Southern Maya Lowlands (from 8.18.10.0.0 with ajaw to 9.17.10.0.0 on Naranjo Stela 19, while with the sajal title the last record is 9.18.1.12.16 on the unprovenanced Dumbarton Oaks Panel); the -le or -le-le forms appears not much later and then spread over the whole Lowlands (from 9.4.11.8.16 to the end of the Classic Period). It is too early to posit that the four titles suffixed only with -li were never suffixed with -le/-le-le because they occur only a couple of times in accession statements, all of them coming from three monuments dedicated between 615 and 660, when both forms were widely used.9

Further on, the contexts of the ajawil/ajawlel and sajalil/sajalel are similar, which in turn rules out a difference in their semantic fields. The three main contexts where these derived nouns occur are accession statements, numbered time-period celebrations and a less well-understood context where they occur following the numbers 9 and 3. In the case of the ajawil/ajawlel pair, both forms appear in all of the three contexts, which lend support to a non-different semantic field hypothesis.

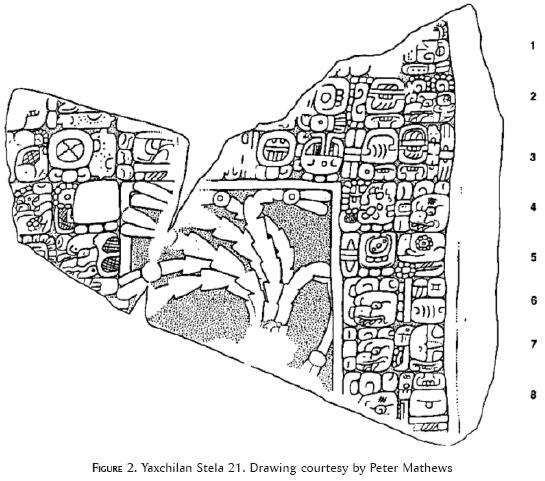

Independently from their similar or different semantic fields, there are no verbs of movement or other toponymic formulas that would indicate that ajawil/ ajawlel refers to territory. There is not a single phrase in the corpus of Classic Period inscriptions where they follow directly verbs such as ochi, huli, tali, puluyi, jub'uyi, t'ab'ayi, e[h]meyi, u[h]ti etc. or where they stand with attested toponyms or substitute with other nouns such as ch'e'n or kab'. Therefore, while both lexemes can be counted, they cannot be conquered or entered into, nobody arrives to ajawil or ajawlel, and most importantly toponyms do not precede or follow them. One inscription, however, may indicate that toponyms were indeed conceived as ajawlel. On the fragmentary inscription of Yaxchilan Stela 21 Itzamnaj B'ahlam IV has various "guardian of X" (uchanul X) titles. He is thus guardian of Tajal Mo' and interestingly 9-AJAW-le, a-MAN-na and a-IK-AJ, the last two well-known agency expressions referring to La Florida and Motul de San José (figure 2, pH:4-pH:8). The expression uchanul b'alun ajawlel may be translated as "the guardian of many kingships or kingdom", nevertheless there is no outside indication to decide between the two alternatives.

All in all, internal evidence shows in the inscriptions that the primary semantic field of both terms is restricted to the actual office. While in the cases of ajaw, sajal and kalomte' this field can be secondarily widened to imply territorial connotations, it is difficult to imagine the same in the case of the office of ch'ok. Confusing the situation more, in case of the accession of Late Classic Tikal rulers from Jasaw Chan K'awil onward, the kalomte' is the explicit title referred to in accession formulas, while the emblem glyph is remaining connected to the ajaw title. At present, Classic Period inscriptions lack explicit pragmatic contexts where either of these lexemes refers to territory.

There are at least two options to interpret the evidence at hand. Either there was no territorial connotation involved during the Classic Period and this was acquired by semantic shift for the Late Postclassic Period, or territorial connotation was not indicated because of genre conventions in the Classic. Whatever is the answer to these two alternatives, the territorial connotation was underrepre-sented in the inscriptions which may hint to differences in the conceptualisation of political organisation between the Classic and the Postclassic Periods. It is probable that the -lei suffix was 'taking over' the grammatical sphere of - il in the case of offices but not having territorial connotations. It is much more probable that ajawlel was an innovation with the institutionalisation of these offices, and the suggestion of Stephen Houston, John Robertson and David Stuart (2001) is more valid with their theory of the development from 'king-ness' to 'kingship'. Indeed, it is possible that use of the -lei suffix reflected a reconceptualisation of the titles and their holders. From Classic Period inscriptions, therefore, there is no evidence for the use of ajawil/ajawlel as a term for 'kingdom'.

Ch'e'n and its Varieties

If ajawil/ajawlel refers to the states of'being king' and the 'institution', the question remains whether there is any other term which could have referred to the concept of 'polity' in a narrower sense, or 'territoriality'.

In their seminal work about Classic Period place names, David Stuart and Stephen Houston (1994: 12) first identified and detailed the occurrences and possible meaning of the variations of a logogram later deciphered by Stuart (published in Vogt and Stuart, 2005) as CH'E'N and represented by T571, T598, T599 and a distinctive bird head with a trilobed element in the eye. They suggested that CH'E'N alone has 'locational associations', and identified two variant combinations with CHAN and KAB', respectively. The first, which they have called 'sky-bone', was attested in their 'place name formula', in iconography, and in texts relating to the 819-day count ritual; the second, according to their data, never occurred in the 'place name formula', but other contexts still indicated an association with locations (Stuart and Houston, 1994: 12). Therefore, the translation of the three expressions -CH'E'N, CHAN-CH'E'N and KAB'-CH'E'N- is 'place' in the current epigraphic literature, however, the exact semantic fields and the differential morphology and contexts have not yet been explained satisfactorily.

Interpretations abound, some of them are not any more valid as the new suggestion CH'E'N and other substitution patterns disqualified them. Linda Schele and Matthew Looper (2004) suggested that CH'E'N and its combinations refer to seats or platforms built from perishable materials where rituals of spirit conjuration occurred. They also suggested that the combination with CHAN refers to "the most sacred parts of cities, perhaps shrines where the gods were kept or where the king was enthroned...[or] to a raised platform", while the combination with KAB' "may indicate a low platform or plaza" (Schele and Looper, 2004: 354).

In contrast, James Brady and Pierre-Robert Colas (2005) proposed that CH'E'N in some expressions connected to warfare may refer to sacred caves and groves, the bread-basket of the k'uhul ajaw. Eric Velasquez (2004: 83-85) also accepts CH'E'N as "cave, whole, rock".10

Alfonso Lacadena (2009: 7-8) came to the conclusion that kab' ch'e'n refers to the concept of "territory? city?" and brings into the discussion the Nawatl di-frasismo altepetl or in atl in tepetl which translates as 'village, city'. Simon Martin maintains that ch'e'n in cases of constructions with ochi, ch'ak, puluyi and the 'Star-War' verb is an abbreviation of the difrasismos kab' ch'e'n and chan ch'e'n with the meaning of "unidades territoriales, sitios de asentamientos humanos poseídos por un gobernante" (Martín, 2004: 105-109).

In contrast to Lacadena (2009) and Martin (2004), David Stuart maintains that chan ch'e'n references the concept of 'world' while kab' ch'e'n is a concept referring to "territory or site" (cited in Velasquez Garcia, 2004: 84). The identification of the specific combinations as difrasismos are widely held by epigraphers, however, Erik Boot (2005: 228) does not accept this analysis, and translates chan ch'e'n as 'place of the well' and kab' ch'e'n as 'region of the well', but later rather confusingly he translates both terms as 'community'.

Stephen Houston (2000: 173) in turn suggested that kab' ch'e'n specifically refers to "land or even to the property of rulers" and he also brought into focus the concept's similarity to the Nawatl altepetl.11

Kerry Hull (2003: 425-438) made a detailed contextual analysis of the kab' ch'e'n, chart ch'e'n and chan kab' expressions, taking them all as difiasismos. He accepted the general meaning of ch'e'n as 'cave' and argued that kab ch'e'n "could be viewed as a reference to a physical location within a site" (Hull, 2003: 427). Conversely, he later cites the idea of David Stuart and concurs that kab' ch'e'n refers to 'territory' and chan ch'e'n is a wider concept with the meaning of 'region'.

Alexander Tokovinine (2008: 141-158) made the most recent and thorough analysis based on a corpora of place names. For him, ch'e'n meant 'temples, holy grounds' and by extension 'city'. The term kab' ch'e'n is simply 'the land and the city' of a person, and he points out that this statement stands in claims of authority over the polity, and he believes that this refers to a notion of 'territory'. In turn chan ch'e'n is related to the notion of sacred landscape, the domain of supernatural entities, and inscriptions mention them where the emphasis is on interaction with such beings (Tokovinine, 2008: 160-161).

The problems of interpretation, therefore, are several: there is no accepted meaning or translation as 'world, region, country, town, village, platform, and cave' have quite different semantic fields. The contextual argument—namely that a given expression is translated differently in different contexts—leads to an under-conceptualisation of one of the most frequent difiasismos in Classic Period inscriptions. In the following I would like to point out some patterns in distribution and use of the ch'e'n, kab' ch'e'n and chan ch'e'n expressions to add some new insights to the debate.

First of all, ch'e'n as others pointed out, has a general meaning of 'cave, whole, pool' and semantically it can refer to any cavity on earth filled or not filled by water.12 As such it is part of the landscape described in Classic Period inscriptions. The other participants of the difiasismos are also well attested, kab' is 'land' but not soil, and chan is 'sky'. Epigraphers agree that ch'e'n is the widest used term in Classic Period inscriptions. Its context suggests that it refers to a built place either by humans or by divine beings (see Tokovinine, 2008: 141-158 for an exhaustive list of these contexts). It is attested from the earliest inscriptions and in every region of the Maya lowlands. Ch'e'n is standing with verbs indicating movement and warfare, and with toponyms.

Kab' ch'e'n and chart ch'e'n behave not alike difrasismos in Colonial Mayan and Nawa language sources (Knowlton, 2002). Such expressions consist of two roots, and when possessed can take ergative pronouns on all of their constituents. Thus we have ukab' uch'e'n and uchan uch'e'n. Such a compound functions as an entire phrase and refers to a third lexeme. Angel Maria Garibay (1953-1954) called this new term difrasismo. Translating these compounds literally (or as stative sentences "his land, his cave") or as periphrastic gentitives ("the land of his cave"), I believe it is erroneous.13 While sometimes such difrasismos are semantically transparent, in other cases epigraphers and linguists have problems to explain why certain terms are used in specific constructions.

Ch'ahb' and ahk'ab' are attested as two nouns independently as 'fast' and 'night'. They form a difrasismo which has, possibly, the connotation of 'person, self as it occurs in a father of child expression where the offspring is the image (ub'ah) of the ch'ahb' ahk'ab' of the father. In captive presentations, it is frequent to refer to the captive as ub'ah ma' ch'ahb'al ma' ahk'b'al which is best translated as 'the image of nobody', in the sense of the self of somebody who lost his personhood by being a captive. Neither a literal translation nor 'captive' explains both contexts, therefore my suggestion to go for a third therm. Taking into account such considerations, kab' ch'e'n and chan ch'e'n may transmit meanings which are not indicated properly by literal translations or using periphrastic interpretations.

The distribution of kab' ch'e'n is temporally wide (from the Early Classic to the Postclassic Periods), but spatially it has a preferential use in the Western Maya Region, with early examples in the inscriptions of Copan and Quirigua in the Southeast Maya Region. Except some cases, it is virtually not used in other regions. Its context is slightly different from that of chan ch'e'n. While the latter is the preferential difrasismo in formulas where it has to follow a toponym as "to-ponym -chan ch'e'n", kab' ch'e'n is extremely rare in this context (Hull, 2003: 428).

This alone lends support to suggestions which posit different semantic fields for these two expressions. Kab' ch'e'n is the preferential expression with verbs such as ch'ak, puluyi and 'Star-War', if a difrasismo occurs at all (Martin, 2004: 108). Also, as Peter Mathews (1996 [1991]: 25) demonstrated the 'Star-War' verb can stand with a toponym, the KAB' and the CH'E'N logograms (these ones frequently possessed, mostly with the third person ergative pronoun; see Martin, 1996: 3, 16). In one particularly enlightening case, the 'Star-War'-yi verb precedes a possessed ukab' ch'e'n on Tonina Monument 83 (Martin, 2004: 108). As Simon Martin concluded at the same page, this specific late example perhaps indicate that ch'e'n is a shorthand form to indicate kab' ch'e'n in 'war expressions', however, it is equally possible that here they refer something different than ch'e'n.

The next context where kab' ch'e'n occurs frequently is a possessed formula with other locative adverbs, mostly found in the inscriptions of the Western Maya Region, especially in Bonampak and Yaxchilan. In these cases it is connected to locations but the emphasis is on the possession and the 'within-ness' of the actions conducted. The earliest example is on an unprovenanced jade from Costa Rica which may unravel some of its semantic meaning. The text is the following (figure 3):

ub'ah 7 7 ix y atan muyal nun 7 tan lam 7 ajaw 7 ub'ah tu kab' tu ch'e'n

"it is her image, Ix ?, she is the wife of Muyal Nun ? Tan Lam ? ajaw ?, it is her image on [his land, on his cave]"

Here, the third person ergative pronouns refers once to the wife and then to the husband, and the little formula at the end emphasise that the wife is on the property of the husband (independently of the translation of kab' ch'e'n). The same formula is continued to be used in various inscriptions, for instance on Brussels Stela B1-C2 (figure 4):

ub'ah[il] an 7 7 k'i[h]nich a[h]ku[I] pat 7-ha' ajawjun winikhab' jun hab' chanlajun winik lajchan k'in chumlaj i pas[aj] tu kab' tu ch'e'n

"it is his image of the ?, ?? [a version of Gill], K'ihnich Ahkul Pat, ? Ha' ajaw, 1 winikhab', 1 hab' 14 winik, 1 k'in since he sat and then appeared [as sun in the horizon] in [his land, in his cave]"

In this context the reference is to an accession but here without the record of the office and the kab' ch'e'n is possessed but it is not certain whether by the king himself (K'ihnich Ahkul Pat) or by the deity impersonated by him. This formula is almost a substitution for the usual chumlaj/wani ti/ta ajawil/ajawlel construction, in which case ajawil/ajawlel is never possessed, a distinction, which probably shows that an office cannot be possessed in the sense as a kab' ch'e'n. It lends support to make a distinction between the abstraction of office and the concreteness of kab' ch'e'n.

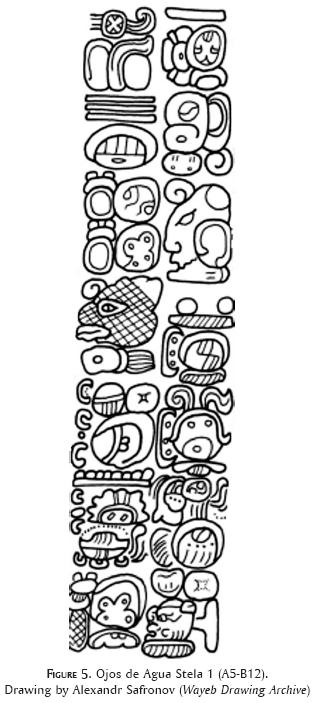

Kab' ch'e'n is possessed in another text replicating the formula of the Brussels Stela (Ojos de Agua Stela, 1, figure 5):

ho' mih winik[i]j ho'Iajun hab' chumlajiy tu kab' tu ch'e'n e[hjb' pat uhuk tz'ak[b'ujl uya-jawte' umijnil aj yax punim i pasaj tu kab' tu ch'e'n xukalnah ajaw

"5 winik 0 day since he sat in [his land, his cave], Ehb' Pat, the seventh successor of the yajawte', the son of Aj Yax Punim, and he opened in [his land, his cave], he is a Xukalnah Ajaw"

The accession sentence is exactly the same as on the Brussels stela which in turn is followed by similar information about the family of the ruler (on the Brussels stela the mother and father are mentioned), hereby followed by a verb which in turn is said to happen again in the land and cave of the ruler who is only recorded as a Xukalnah lord.

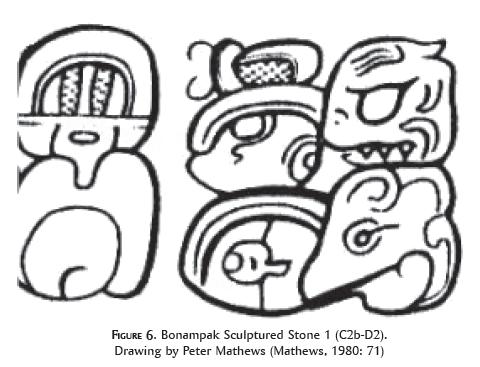

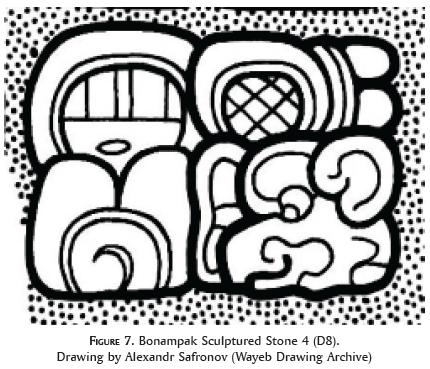

Another interesting context of the kab' ch'e'n difrasismo is its connection to the verb "HAB' "-yi,14 which precedes toponyms. In this context, the usual term is ch'e'n. For instance, in Bonampak Sculptured Stone 1 (C2b-D2, figure 6) a future period ending is followed by "HAB'"-Vy tu kab' tu ch'e'n usij witznal. Usij witznal is the name of Bonampak. On Bonampak Sculptured Stone 4 (D8, figure 7) it is simply written "HAB'"-Vy tu ch'e'n.

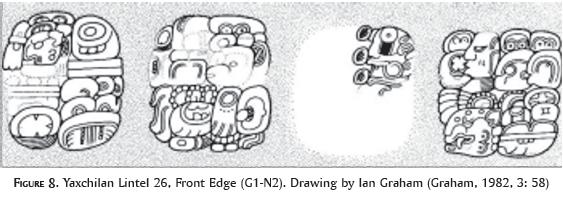

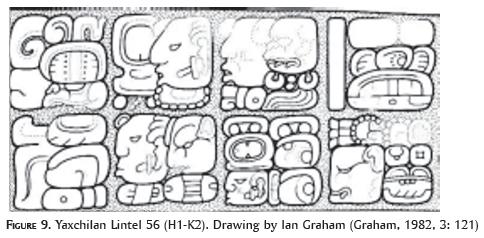

Another context which is similar and not exactly toponymic is on the front edge of Yaxchilan Lintel 26 (Nl, figure 8) where a house dedication is mentioned (ochi k'a[h]k' ? uk'uh[ul] k'ab'a' yototj by Ix K'ab'al Xok; as the first clause ends a second one begins with ukab' uch'e'n and continues with the name of the current Yaxchilan ruler. Although it was tempting to see this as a similar sequence to ukab'jiy transitive verb events (and it is easy to see here an etymologic connection between the two), it is arguable that the second clause only states that the house (otot), the physical building is the kab' ch'e'n of the Yaxchilan ruler, albeit it is the house of Ix K'ab'al Xok. A similar sentence is recorded on Yaxchilan Lintel 56 (figure 9) where the house (otot) of Ix Sale B'iyan is in turn the kab' ch'e'n of Itzamnaj B'ahlam III.

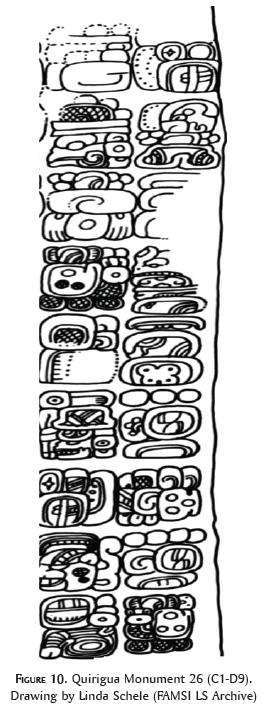

These two similar sentences can clear off some of the doubts about the semantic field of kab' ch'e'n. As in the Costa Rica jade, the kab' ch'e'n here is possessed not by the subject of the first clause but by another grammatical subject, in both cases rulers whose wives participate in various rituals. In the cases of the Yaxchilan Lintels, I cannot emphasise enough that these are the houses (otot) which are the kab' ch'e'n of the ruler. As there are only two examples, somebody can argue that a missing tu is not written in both cases, because a general translation of "in the community of" would be possible; however, I doubt that this was the case. Rather, the houses were the properties or better, objects owned by the Yaxchilan kings, while they also pertained to the women who lived in them. An early form of the use of kab' ch'e'n can be interpreted in a similar way, although the context is not well understood. Quirigua Monument 26 (figure 10) lists probably three rulers in succession (the second, third and fourth one) in different rituals:

? k'uhul ajaw "HEADBAND-BIRD" k'uhul ? t'o-7 7u[kab' ch'e'n?] cha' ch'ajom ?-Vp paswani ukab' ch'e'n ? ux tz'akb'ul ajaw[a]j ? ub'ah ? chan tz'akb'ul chan yopat jun ch'ajom k'uhul ?

"? the sacred lord, the "headband bird", the sacred ?, ?, his [land-cave], of the two (winikhab') ch'ajom (from) ?-Vp, it was opened [his land-cave], of ?, the third successor, he became lord, ? it is his image, the fourth successor Chan Yopat, one (winikhab') ch'ajom, the sacred ?"

The text, although opaque, records that the kab' ch'e'n, possessed by a once lived individual, is opened. Even in a metaphorical way, it is difficult to imagine the opening of a community or region, however, some property, a physical entity such as a tomb can be easily reopened and rituals can be carried on as was attested in other inscriptions (Fitzsimmons, 1998).

In these particular cases a 'territory, city, community' or 'world' translation seems inappropriate. Almost always a kab' ch'e'n is possessed, therefore pertaining to a person, nevertheless by using the word 'property' and 'possession' I do not want to imply private property in the sense of industrialised capitalist societies. Rather, kab' ch'e'n is emphasising the land and the buildings, and probably the very physicality of these artificial creations. Dominion may be an appropriate term to translate kab' ch'e'n. Dominion or domain can refer to a singular building to a wider territory, but at the same time it emphasises some personal ownership. While ch'e'n referred to the built area of a city, kab' ch'e'n was all that was under the dominion of a person.

The context of the use of chan ch'e'n differs from that of kab' ch'e'n in various ways. Chan ch'e'n is the preferred expression after toponyms without any locative preposition. The possession of chan ch'e'n is rare (for example Copan Altar S, figure 11), while kab' ch'e'n stands most of the cases modified by the third person or sometimes with the second person ergative pronouns. Chan ch'e'n never follows verbs such as ch'ak, puluyi, huli, e[h]meyi, t'ab'ayi, etc. Chan ch'e'n is the one which follows the various cardinal directions such as 'north, south, west, east' in the 819 day-count formula. Outside of this context, as on an Altar for Copan Stela 13 (G1-H1, figure 12), it also refers to cardinal direction:

alay patlaj u we' huk chapat tz'ikin k'inich ajaw elk'in chart ch'e'n

"here he formed the food for Huk Chapat Tz'ikin K'inich 7Ajaw [at] the East [place]"

Chan ch'e'n sometimes seems to be an abbreviation of ch'e'n (Hull, 2003: 429-430). This is attested in two different contexts during the Early Classic Period.

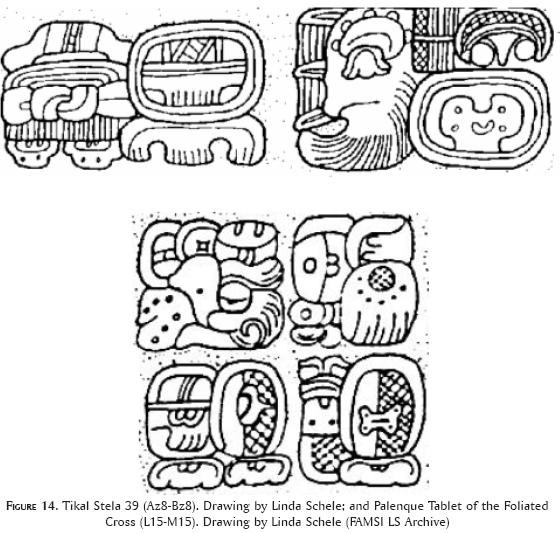

On the Tikal Marcador (figure 13), the arrival of Sihjay K'ahk' is mentioned to be at Mutul chan ch'e'n (B9); in the same text (H5-I5) another arrival is happened at Mutul ch'e'n. Another context where the substitution occurs is the formula, usually at the end of a sentence, "toponym chan ch'e'n uch'e'n X" (figure 14) attested in the Early Classic Tikal Stela 39 (Az8-Bz8). Or in the Late Classic Palenque Temple of the Foliated Cross Tablet (L15-M15) where the text ends with u[h]tiy lakam ha' chan ch'e'n tu ch'e'n or "it happened at Lakam Ha' chan ch'e'n, in the ch'e'n of...". It is not clear whether the place name here is referred to as a ch'e'n of a given being (that is Lakam Ha' is referenced back by tu ch'e'n) or in this case a specific building is what is a ch'e'n within a wider Lakam Ha' chan ch'e'n. That ch'e'n can refer to buildings alone without any prior mention of chan or kab' ch'e'n is attested in various inscriptions, where the possessors are deities.

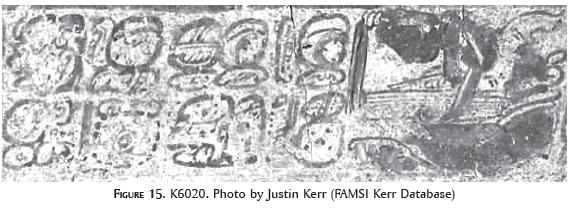

On K6020 (figure 15), a similar clause occurs at the end of a larger narrative, which is unfortunately not well understood. The clause ends with u[h]tiy ? nal chan ch'e'n uch'e'n b'i-? tz'i[h]b' or 'it happened at the ? sky cave, the cave of B'i-?, the scribe'. This scribe is even represented as sitting in front of the written text reading a codex. Therefore, it is possible that he was reading out the story and ch'e'n actually refers to his 'place', or even to the codex, or better said just indicates that the scribe was from a mythological place attested in other inscriptions (Stuart and Houston, 1994: 74).

The distribution of chart ch'e'n is not connected to one kind of toponym as it follows emblem glyph main signs, other toponyms and especially mythological place names, and also cardinal directions. While -nal is a frequent suffix on toponyms attested from the earliest inscriptions cuing generally 'place' and it forms part of actual toponyms, chan ch'e'n may indicate an added quality acquired by the presence of inhabitants, the only common and implied factor present in all the toponyms connected to chan ch'e'n.

According to these selected contexts ch'e'n refers to the smallest unit of the landscape with the meaning of 'inhabited place, settlement'. Kab' ch'e'n refers to the 'dominion' of somebody and this sometimes encompasses a wider area than a single settlement. Chan ch'e'n has the meaning of'place' which can be real or imaginary, mostly the latter. Finally, chan kab' has the meaning of 'world, everywhere'.15

Using one single word (ch'e'n) to refer to a range of settlements, which archaeologists differentiate by size and complexity (hamlets, villages, town and city), is not unique to the Classic Maya. Ancient Sumerian terminology did not distinguish among settlements which were uniformly designated 'uru' in cuneiform texts (Glassner, 2000: 38; Westenholz, 2002: 28).

Conclusion

I have suggested that Classic Maya politics can be approached by the analysis of certain words pertaining to the arena of politics, together constituting a political vocabulary. There are many more words which can be examined, and I do not claim to have made a thorough analysis. From these reflections I propose the following observations for further investigation.

Classic Period polities may had been referred to as ch'an ch'e'n or simply ch'e'n. This word, however, cannot be equated one to one to 'polity' or 'state', rather it referred to places where humans and supernatural entities lived together. Therefore, I speculate that it could refer to a building, a group of buildings, a plaza group or many plaza groups together or what we call 'city' in general.

The Classic Period ajawil/ajawlel referred to a ruling line, the office of the ajaw, and presumably later incorporated a more specific territorial meaning also, though I do not see this borne out of Classic Maya inscriptions, rather it is an assumption coming from investigations of Postclassic Maya societies (whose data come from the Colonial Period). A polity was composed from inhabited places which were all designated as ch'e'n where kingship was institutionalised (ajawlel). This constellation was similar in many ways to the Postclassic Mexican Highland polity organisation with its altepetl and the institution of the tlahtocayotl which corresponded to the Classic Maya ajawlel.

REFERENCES

Akkeren, Ruud W, 2003 "Authors of the Popol Wuj", Ancient Mesoamerica. 14 (2): 237-256. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Beliaev, Dmitri, 2001 "T550 as a Verb for 'Return'". Unpublished manuscript. [ Links ]

Bolles, David, 1997 Combined Dictionary Concordance of the Yucatecan Mayan Language <http://www.famsi.org/reports/96072/index.html>. [Retrieved September 26, 2011. [ Links ]]

Boot, Erik, 2005 Continuity and Change in Text and Image at Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico: AStudy of the Inscriptions, Iconography, and Architecture at a Late Classic to EarlyPostclassic Maya Site. Leiden [Netherlands]: Universiteit Leiden, Centre of Non-Western Studies Publications. [ Links ]

Brady, James and Pierre-Robert Colas, 2005 "Nikte Mo' Scattered Fire in the Cave of K'ab Chante': Epigraphic and Archaeological Evidence for Cave Desecration in Ancient Maya Warfare", Houses and Earth lords: Maya Religion in the Cave Context, Keith M. Prufer and James E. Brady (eds.). Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 149-166. [ Links ]

Braswell, Geoffrey E. 2001 "Post-Classic Maya Courts of the Guatemalan Highlands: Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Approaches", Royal Courts of the Ancient Maya: 2. Data and Case Studies. Takeshi Inomata and Stephen D. Houston (eds.). Boulder: Westview Press, 308-334. [ Links ]

Bricker, Victoria R. 1986 A Grammar of Maya Hieroglyphs. New Orleans: Tulane University (Middle American Research Institute Publication, 56). [ Links ]

Carrasco, Michael, Kerry Hull and Robert Wald, n.d. "An Introduction to Epigraphic Mayan: A Notebook for the Workshop on Maya Hieroglyphic Writing for Summer Intensive Course in Yucatec Mayan". Unpublished manuscript. [ Links ]

Ciudad Ruiz, Andrés and Alfonso Lacadena, 2001 "Tamactún-Acalán: interpretación de una hegemonía política maya de los siglos XIV-XVI", Journal de la Société des Américanistes, 87: 9-38. París: Société des Américanistes. [ Links ]

Christenson, Allen J. 2007 Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Quiche Maya <http://www.mesoweb.com/publications/Christenson/index.html>. [Retrieved September 26, 2011. [ Links ]]

Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions 1977-, Volumes 1-9. 1977 Ian Graham (general editor). Cambridge: Harvard University, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. [ Links ]

England, Nora, 1983 A Grammar of Mam, a Mayan Language. Austin: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Fitzsimmons, James, 1998 "Classic Maya Mortuary Anniversaries at Piedras Negras, Guatemala", Ancient Mesoamerica, 9: 271-278. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Fox, John W, 1987 Maya Postclassical State Formation: Segmentary Lineage Migration in AdvancingFrontiers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Fox, John W and Garrett W Cook, 1996 "Constructing Maya Communities: Ethnography for Archaeology", CurrentAnthropology, 37 (5): 811-821. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Freidel, David and Linda Schele, 1988 "Kingship in the Late Preclassic Maya Lowlands: the Instruments and Places of Ritual Power", American Anthropologist, 90 (3): 547-567. Arlington [United States]: American Anthropological Association. [ Links ]

Garibay, Ángel María, 1953- Historia de la literatura náhuatl. México: Porrúa (Biblioteca Porrúa, 1). 1954 [ Links ]

Glassner, Jean-Jacques, 2000 "Les petit Etats mésopotamiens: á la fin du 4e et au cours du 3e millénai-re", A Comparative Study of thirty City-State Cultures, Mogens Herman Hansen (ed.). Copenhagen: Reitzels Forlag/The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, 35-53. [ Links ]

Graham, Ian, 1982 YaxchiIan-3, Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions. Cambridge [United States]: Harvard University, Peabody Musem of Archaeology and Ethnology. [ Links ]

Grube, Nikolai and Simon Martin, 2001 The Coming of Kings: Writing and Dynastic Kingship in the Maya Area Between the Late Preclassic and the Early Classic, Notebook for the XXX Maya Hieroglyphic Forum at Texas, 2001. Austin: University of Texas at Austin, Department of Art History. [ Links ]

Houston, Stephen D. 2000 "Into the Minds of Ancients: Advances in Maya Glyph Studies", journal of World Prehistory, 14 (2): 121-201. New York: Kluwer Academic Press. [ Links ]

Houston, Stephen D. and David Stuart, 1996 "Of Gods, Glyphs, and Kings: Divinity and Rulership among the Classic Maya", Antiquity, 70: 289-312. York: University of York. [ Links ]

----------, 2001 "Peopling the Classic Maya Court", Royal Courts of the Ancient Maya, vol. 1, pp. 54-83; Inomata, Takeshi and Stephen D. Houston (eds.). Boulder [United States]: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Houston, Stephen D.,John Robertson and David Stuart, 2000 "The Language of Classic Maya Inscriptions", Current Anthropology, 42 (3): 321-356. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

----------, 2001 Quality and quantity in glyphic nouns and adjectives (Calidad y cantidad en sustantivos y adjetivos glificos). Barnardsville [United States]: Center for Maya Research (Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing, 47). [ Links ]

Houston, Stephen D. et al. 2003 "The Moral Community: Maya Settlement Transformation at Piedras Negras, Guatemala", The Social Construction of Ancient Cities, Monica Smith (ed.). Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution Press, 212-253. [ Links ]

Hull, Kerry, 2003 Verbal Art and Performance in Ch'orti' and Maya Hieroglyphic Writing, PhD Thesis. Austin: University of Texas, Department of Art History. [ Links ]

Kaufman, Terrence and John Justerson, 2002 "A Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary", FAMSI Foundation for the Advancement ofMesoamerican Studies, Inc. <http://www.famsi.org/reports/01051/index.html>. [Retrieved September 26, 2011. [ Links ]]

Kerr, Justin, "Classic Maya Vase Database", FAMSI Foundation for the Advancement ofMesoamerican Studies, Inc. <http://research.mayavase.com/kerrmaya.html>. [Retrieved September 26, 2011. [ Links ]]

Knowlton, Timothy, 2002 "Diphrastic Kennings in Mayan Hieroglyphic Literature", Mexicon, 24: 9-14. Markt Schwaben: Verlag Anton Saurwein. [ Links ]

Koselleck, Reinhart, 2003 Elmúlt jóvo: A tórténeti idoszak szemantikája. Budapest: Atlantisz Kiadó [ Links ].

Lacadena, Alfonso, 2009 "Apuntes para un estudio sobre literatura maya antigua", Text and Context:Yucatec Maya Literature in a Diachronic Perspective, Tsubasha Okoshi Harada, Antje Gunsenheimer and John F. Chuchiak (eds.) Aachen [Germany]: Shaker Verlag (Bonner Amerikanistische Studien, 47), 31-52. [ Links ]

Lacadena, Alfonso and Andrés Ciudad Ruiz, 1998 "Reflexiones sobre estructura política maya clásica", Anatomía de una civilización. Aproximaciones interdisciplinarias a la cultura maya, Andrés Ciudad Ruiz et al. (eds.). Madrid: Sociedad Española de Estudios Mayas, 31-64. [ Links ]

Lacadena, Alfonso and Soren Wichmann, 2002 "The Distribution of Lowland Maya Languages in the Classic Period", Laorganización social entre los Mayas prehispánicos, coloniales y modernos, Vera Tiesler Blos et al. (eds.). Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 275-320. [ Links ]

----------, 2004 "On the Representation of the Glottal Stop in Maya Writing", The Linguistics of Maya Writing, Soren Wichmann (ed.). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 100-164. [ Links ]

Laughlin, Robert M. and John Haviland, 1988 The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of Santo Domingo Zinacantan: with GrammaticalAnalysis and Historical Commentary. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press (Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, 31). [ Links ]

Leftwich, Adrian, 2004 What is Politics? The Activity and its Study. Oxford: Polity. [ Links ]

MacLeod, Barbara, 2004 "A World in a Grain of Sand: Transitive Perfect Verbs in the Classic Maya Script", The Linguistics of Maya Writing, S0ren Wichmann (ed.). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 291-326. [ Links ]

Martín, Simon, 1996 "Tikal's Star Wars Against Naranjo", Eighth Palenque Round Table, 1993, Martha J. Macri and Jan McHargue (eds.). San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 223-236. [ Links ]

----------, 2004 "Preguntas epigráficas acerca de los escalones de Dzibanche", Los Cautivos de Dzibanché, Enrique Nalda (ed.). Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes/Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 105-115. [ Links ]

Mathews, Peter, 1980 "Notes on the Dynastic Sequence of Bonampak, Part 1", Third PalenqueRound Table, Part 2, Merle Greene Robertson (ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press, 60-73. [ Links ]

----------, 1991 [1996] "Classic Maya Emblem Glyphs", Classic Maya Political History: Epigraphic and Archaeological Evidence, Patrick T. Culbert (ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 19-29. [ Links ]

Mathews, Peter and John Justeson, 1984 "Patterns of Sign Substitution in Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing: the Affix Cluster", Phoneticism in Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing, John S. Justetson and Lyle Campbell (eds.). Albany: State University of New York at Albany (Institute for Mesoamerican Studies Publication, 9), 185-231. [ Links ]

Miller, Mary E. and Simon Martin (eds.), 2004 "Courtly Art of the Ancient Maya". New York: Thames and Hudson. [ Links ]

Mora-Marin, David, 2005 "Proto-Ch'olan as the Standard Language of Classic Lowland Mayan Texts". Unpublished manuscript. [ Links ]

Richter, Melvin, 1986 "Conceptual History (Begriffsgeschichte) and Political Theory", Political Theory, 14 (4): 604-637. Evanston [Illinois]: Northwestern University, Department of Political Science. [ Links ]

----------, 1987 "Begriffsgeschichte and the History of Ideas", Journal of the History of Ideas, 48 (2): 274-263. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [ Links ]

Sattler, Mareike, 2004 "Ch'olti": an Analysis of the/Irte de la Lengua Ch'olti' by Fray Francisco Moran", The Linguistics of Maya Writing. Soren Wichmann (ed.). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 365-407. [ Links ]

Schele, Linda, "The Linda Schele Drawing Collection", FAMSI. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. <http://www.famsi.org/research/schele/index.html>. [Retrieved September 26, 2011. [ Links ]]

Schele, Linda and Matthew Looper, 2004 "Seats of Power at Copan", Copan: The History of an Ancient Maya Kingdom, E. Wyllys Andrews and William L. Fash (eds.). Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 345-372. [ Links ]

Schmidt, James, 1999 "How Historical is Begriffsgeschichte?", History of European Ideas, 25: 9-14. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [ Links ]

Skinner, Quentin, 2002 Visions of Politics, Volume I: Regarding Methods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Smailus, Ortwin, 1975 El maya-chontal de Acalán: análisis lingüístico de un documento de los años 1610-12. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Coordinación de las Humanidades (Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios Mayas, 9). [ Links ]

----------, 1989 Vocabulario en Lengua Castellana y Guatemalteca que se llama Cakchiquel Chi: Análisis gramatical y lexicológico del Cakchiquel colonial según un antiguo diccionario anónimo. Hamburg: Wayasbah Verlag (Wayasbah Publication, 14). [ Links ]

Stuart, David, 2003 "The Paw Stone: The Place Name of Piedras Negras, Guatemala", PARÍ Journal, 4 (3):l-6. San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute. [ Links ]

Stuart, David and Stephen D. Houston, 1994 Classic Maya Place Names. Washington D. C: Dumbarton Oaks (Studies in Precolumbian Art and Archaeology, 33). [ Links ]

Tokovinine, Alexander, 2008 "The Power of Place: political landscape and identity in Classic Maya inscriptions", PhD Thesis. Cambridge: Harvard University, Department of Anthropology. [ Links ]

Velasquez Garcia, Erik, 2004 "Los escalones jeroglíficos de Dzibanché", Los Cautivos de Dzibanché, Enrique Nalda (ed.). Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes/ Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 73-103. [ Links ]

Vogt, Evon Z. and David Stuart, 2005 "Some notes on ritual caves among the ancient and modern Maya", In the Maw of the Earth Monster: Mesoamerican Ritual Cave Use, James E. Brady and Keith M. Prufer (eds.). Austin: University of Texas Press, 155-185. [ Links ]

Wald, Robert, 2004 "Telling Time in Classic-Ch'olan and Acalan-Chontal Narrative: The Linguistic Base of Some Temporal Discourse Patterns in Maya Hieroglyphic and Acalan-Chontal Texts", The Linguistics of Maya Writing, Soren Wichmann (ed.). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 211-258. [ Links ]

Westenholz, Aage, 2002 "The Sumerian City-State", A Comparative Study of Six City State Cultures, Mogens Herman Hansen (ed.). Copenhagen: Reitzels Forlag/The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, 23-42. [ Links ]

Wichmann, Soren, 2006 "Mayan Historical Linguistics and Epigraphy: A New Synthesis", Annual Review of Anthropology, 35: 279-294. Palo Alto [California] [ Links ].

Wisdom, Charles, 1950 "Materials on the Chortf Languages", Microfilm collection of manuscripts on Middle American Cultural Anthropology, 28. University of Chicago, Joseph Regenstein Library, Chicago. [ Links ]

Zender, Marc, 1999 "Diacritical Marks and Underspelling in Classic Maya Script: Implications for Decipherment", MA Thesis. Calgary: University of Calgary, Department of Archaeology. [ Links ]

----------, 2004 "A Study of Classic Maya Priesthood", PhD Thesis. Calgary: University of Calgary, Department of Archaeology. [ Links ]

* I began to write this paper in 2009 at La Trobe University, Australia. I continue the article at the Instituí für Altamerikanistik at Bonn, Germany. In Australia I received funding from a La Trobe University Posgraduate Research Scholarship and also from an International Posgraduate Research Scholarship, while in Germany my stay is financed by the Humboldt Stiftung. I would like to thank to Peter Mathews his help during my stay in Melbourne. I cannot thank enough the kind offer of Nikolai Grube to work in Bonn. My research benefited from ideas of many colleagues such as Dmitri Beliaev, Alexander Safronov, Albert Davletshin, Christian Prager, Elisabeth Wagner, Guido Krempel and Barbara MacLeod. I thank Doorshysingh Jugessur for reading the manuscript and correcting it.

1 The Western Maya Region is more a political than a geographic region. The rulers within this region had more interactions with each other than with other rulers outside of the region, at least according to the attestation of their inscriptions. This area is stretching from the Chiapas highlands to the San Pedro River encompassing the Usumacinta River valley. The most important sites were Comalcalco, Tortuguero, Tonina, Palenque, Pomona, Moral, Santa Elena, La Florida, Piedras Negras, Yaxchilan, Bonampak, Lakanha and the still elusive Sak Tz'i'.

2 In my transliteration and transcription I do not indicate complex vowels and I indicate glottal stop and glottalised consonants (b', k', tz', etc.) with an apostrophe. Transcriptions are in bold (upper case logograms and lower case syllabograms), transliterations are in italics and translations are between double quote signs.

3 Concepts are widely investigated and hotly debated, indeed 'concept' is one of those words that scholars use succesfully but not able to define consensually. I use 'concept' here as a sort of abstraction which subsumes various specific instances under one unit of meaning and helps to form more abstractions in turn.

4 It is important to emphasise that those are not all available political terms used by the elite or other members of the society. These are words and terms which were selected and kept maintained for expressing something ideal, most probably in practice seldom achieved.

5 The relationship between concepts and words are well phrased by Skinner:

The surest sign that a group or society has entered into the self-conscious possession of a new concept is that a corresponding vocabulary will be developed, a vocabulary which can then be used to pick out and discuss the concept in question with consistency [...] there is a systematic relationship between words and concepts. To possess a concept is at least standardly to understand the meaning of a corresponding term (and to be able in consequence to think about the concept when instances are absent and recognise it when instances are present (Skinner, 2002: 160).

6 To illustrate with an example what semantic field means, I present here the conceptualisation of 'knowledge' in Middle High German by Richter (1986). Both in 1200 and in 1300 there were three different words which referred to certain aspect of a concept now designated with the word 'knowledge', that is there were two different synchronic states:

1200: wisheit, kunst, list

1300: wisheit, kunst, wizzen

About 1200 kunst designated higher, courtly forms of knowledge; fot, lower, noncourtly, technical knowledge and skills; wisheit could serve as an alternative to either kunst or fot, or as their synthesis: "viewing man as a whole and merging intellectual, moral, courtly, aesthetic, and religious elements into social standing." By 1300 the linguistic field had been transformed. Knowledge was now designated by terms meaning very different things from the three terms used a century before. First, the meaning of each separate term has altered; second, the relationship among them had shifted. Wisheit had taken on an exclusively religious, indeed mystical sense. Thus it could no longer be used either as an alternative to the other two or as a synthetic term joining them. As for kunst, by 1300 it had lost the courtly and social senses it had carried a century before. List, because of pejorative senses connected about 1300 with magic and low cunning, dropped out of the sphere of intellectual terms. Wizzen now turned into a key term within a linguistic field that functioned within a society itself profoundly changed from that of 1200. A distinction was opening up between "knowledge" and "art." What is reflected in these changes is that neither feudal relationships nor the difference among courtly achievements were meaningful, as they had been in the previous century (In modern German Kunst means "art"; Weishelt, "wisdom"; List, "cunning," "craft"; Wissen, "knowledge," "learning.") (Richter 1986: 626).

7 "One of the functions of -VI suffixes is to derive abstract nouns from concrete ones, and class names from specific instances; in the case of words for titles or ranks, they derive names of offices. The use of -VI suffixes in this context is thus consistent with the evidence above that the seatings and accessions referred to in Mayan hieroglyphic texts were 'to the lordship' (an office), and not 'as lord' (rank)." (Mathews and Justeson, 1984: 228).

8 In a fragmentary Tonina inscriptions there is a short text written as 19-su-SUTZ' i-JOY-ja ta-sa-ja-le u-?-ki 9-7/19 sutz' i joy [aft ta sajalefl] u-?Vk 9-1 In the case of KAL-ma-TE'-le (attested in Tikal Temple I, Lintel 3: E10) there are two possible transliterations: kalomte'l and kalomte'le[lj. As there is no evidence of a vowel concordant -VI abstractive suffix, I believe that this example is similar to ajawlel and sajalel.

9 These data come from Alfonso Lacadena and S0ren Wichmann (2002).

10 He additionally wrote that:

En mi opinión, la palabra ch'en, "cueva, pozo" o "roca", parece referirse a un sitio que se encuentra tanto en el centro del cielo (chan ch'en) como en el de la tierra (kab ch'en), mismo que está representado en algún lugar físico considerado como el corazón del reino o ciudad (Velásquez García, 2004: 85).

11 In a later article (Houston et al, 2003: 241) he mentions that:

The only general term for location, often in association with maximal or "holy" lords, reads KAB'-CH'E:N, "earth-cave" (David Stuart, personal communication, 1998). This locative expression is not, in our opinion, an abstract concept for "dominion", "city", or "kingdom", but a concrete reference to Maya places, which combine earth and rocky outcrops and caves—the very image of a karstic landscape.

12 The different cognates of the proto-Mayan "k'e'n/cave are listed in Kaufman and Justeson, 2002: 432.

13 In Mayan languages, just as in Classic Ch'olan, there are compound and complex nouns (England, 1983: 70; Carrasco, Hull, and Wald n.d.). Compounds contain two roots but they refer to a single lexeme. When it is possessed, the ergative precedes the compound and the enclitic follows it (examples in Classic Ch'olan are u-lakamtun-il, u-k'altun-il, y-etkab'a'-il etc.). Complex nouns contain two roots, where the first is possessed by the second, however this phrase refers to a single lexeme. When a complex noun is possessed it is only the second root which receives the possessive affixes. Such complex noun are rare in Classic Ch'olan. Difrasismos can be added to this system. They contain two roots which express one single lexeme but when they are possessed the ergative precedes both roots (u-b'akil u-jolil, u-ch'ahb'il y-ahkb'a-l etc.).

14 Unfortunately this verb is undeciphered, though Dmitri Beliaev (2001) suggested a reading of 'to return', while David Stuart (2003) argued for a general meaning of'to fund'.

15 Chan kab' ajawwas a title used mainly in the inscriptions of Quirigua and Copan, from the Early Classic Period, and it never occurs with toponyms. This signals that its reference cannot be found within the imagined landscape of the Classic Period elite as it is a more encompassing term than one concrete inhabited place. Nevertheless, rulers and groups of deities sometimes were ascribed to this difiasismo, probably expressing a concept of authority (Hull, 2003: 431-437).

Información sobre el autor

Péter Bíró. Húngaro. Historiador y epigrafista en el Abteilung für Altamerikanistik de la Universidad de Bonn, Alemania. Realizó sus estudios de licenciatura en historia en la Universidad de Szeged, Hungría, y de maestría en estudios mesoamericanos en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la UNAM. El doctorado en arqueología lo cursó en la Universidad de La Trobe en Australia. Entre sus trabajos publicados se encuentran los siguientes: "A new look on the inscription of Copan Altar K", "Piedras labradas 2. 4 y 5 de Bonampak y los reyes de Xukalnah en el siglo 7" y "Classic Maya Polity, Identity, Migration and Political Vocabulary. Reconceptualisation of Classic Period Maya Political Organisation".