Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Estudios de cultura maya

versión impresa ISSN 0185-2574

Estud. cult. maya vol.31 Ciudad de México 2008

Artículos

Excavations at Rio Bec Group B, Structure 6N-1, Campeche, Mexico

Prentice M. Thomas y L. Janice Campbell

Prentice Thomas and Associates, Inc. pmthomas@pta-crm.com y jcampbell@pta.crm.com

Abstract

The 1976 investigations produced three major findings. One, Structure 6N-1 was originally constructed and occupied by Late Classic people, probably as an elite residence that likely served public functions as well. Two, the Late Classic people made structural modifications to accommodate the addition of the twin towers. Three, the final activity at 6N-1 occurred during the Terminal Classic period.

Resumen

Las investigaciones de 1976 dieron como resultado tres hallazgos importantes. Primero, que la Estructura 6N-1 fue originalmente construida y ocupada por los habitantes del Clásico Tardío, probablemente como vivienda para la elite, pero que, a su vez, funcionaba como espacio público. Segundo, los habitantes del Clásico Tardío llevaron a cabo cambios estructurales en el edificio para adaptar las torres gemelas. Y tercero, que las últimas actividades en la Estructura 6N-1 tuvieron lugar durante el periodo Clásico Terminal.

The site of Rio Bec in Campeche, Mexico (figure 1),1 was first reported by Comte Maurice de Perigny in 1908, but Group B was not among the ruins he found. That discovery belongs to Robert E. Merwin, who, accompanied by Clarence L. Hay, was traveling in southern Yucatan in 1912 when they came upon Rio Bec B, referring to the principal building, Structure 6N-12 as the "best preserved building found in the region" (Merwin, 1913: 79). Subsequently, Hay (1935) published an article in the Journal of Natural History relating the discovery of Rio Bec Group B along with a description of the principal structure. In 1933, Karl Ruppert and John Denison reached Rio Bec on their Carnegie Expedition and initiated a reconnaissance of the ruins. Ruppert and Denison (1943) identified previously unreported structures, but their efforts to find several groups reported by Merwin were unsuccessful, including the relocation of Structure 6N-1.

Hay's publication represented the last first-hand report on Rio Bec Group B. For 60 years, the site was essentially "lost," at least to the archaeological community, but the situation changed when it was relocated in 1973 by filmmakers, Hugh and Suzanne Johnston, led by Juan de la Cruz Briceño Ramírez, then the caretaker at Becan, and accompanied by Gilette Griffin of Princeton University. Although no archaeological investigations were undertaken during the 1973 field season, the ruins (figure 2) were partially cleared and filmed for a Public Television Services documentary entitled Mystery of the Maya.

Overview of the 1976 Field Season

Following the site's rediscovery, the first controlled excavations at Rio Bec were undertaken in 1976. Directed by the primary author, the work was sponsored by the University of the Americas (UDLA) and partially funded by a grant from the Jenkins Foundation. The primary focus of fieldwork was Structure 6N-1. A secondary aspect was to survey the area immediately surrounding 6N-1 to produce an accurate and complete map of the ruins of Group B as they existed in 1976 (figure 3).

While our team was in the field, there occurred changes in Cholula, Puebla, with respect to the future of the university. As a result, the post-field phases of our Rio Bec project were not funded. A preliminary analysis of artifacts was undertaken concomitant with fieldwork, with plans for a formal review of the data to follow, but events transpiring at UDLA eclipsed those plans. Aspects of the UDLA-sponsored 1976 investigations were subsequently disseminated in papers and theses prepared by several students from our group, but a comprehensive report of findings was not completed. The opportunity to revisit this work began when the French archaeological team working on Proyecto Rio Bec since 2002 initiated correspondence regarding our data from Structure 6N-1. At their invitation, we collaborated in a symposium at the VII Congreso Internacional de Mayistas, held in Merida in July of 2007, leading to an expansion of that presentation for publication and the first formal description of the excavations and findings. The chronological interpretations are based on Stan Freer's ceramic field analysis, Charlotte Arnauld's (personal communication, 2007) excavation data at Group B, and an independent review of the ceramics, which are housed at the INAH facility in Merida, by Nidia E. Rojas Durán.

Following our work at Structure 6N-1, excavations were undertaken by Ramón Carrasco et al. (1986), Agustín Peña Castillo (1998) and Arnauld (2007), with each effort providing important data on the prehistoric occupation at Rio Bec Group B.

Plaza Excavations

Archaeological efforts began in 1976 with the establishment of a grid system, and horizontal and vertical control was maintained by reference to the datum at N100/E130. The first excavations were concentrated on the plaza where sixty 2 m by 2 m units3 were aligned to form a large block excavation (figure 4).

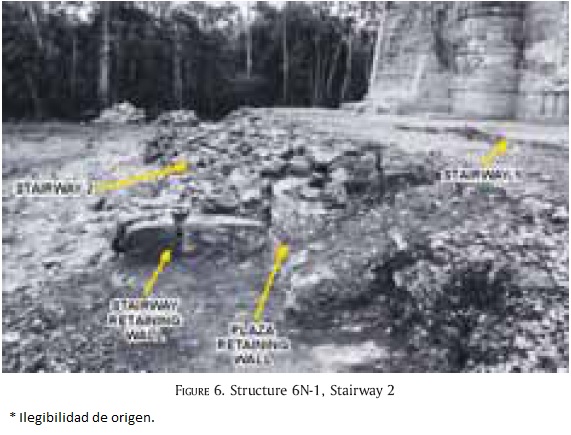

The plaza excavations uncovered a buried stairway two and a half meters due east of the entry stairway into Room C (figure 5). Designated "Stairway 1", it was composed of five steps of cut limestone blocks rising to a small initial plaza that originally fronted the structure. Stairway 1 was covered when the plaza was enlarged and a new stairway (Stairway 2) was constructed. Also consisting of five steps, Stairway 2 was constructed of rows of roughly-shaped limestone slabs with limestone cobbles set between the risers. A north-south retaining wall composed of at least two large, roughly-shaped rectangular limestone blocks flanked the stairway on the north and south sides (figure 6). Subsequent work by Carrasco et al. (1986) and Arnauld (2007) independently confirmed the existence of both the first and second stairways. A cache (Cache 2), consisting of a lidded, unslipped vessel containing a jadeite fragment and a chert projectile point was recovered beneath the surface of the expanded plaza.

In general, however, cultural materials were sparse in plaza units, with most yielding fewer than 200 ceramics from the present surface to bedrock. This scarcity is consistent with the plaza having been swept clean during most of the occupancy. An exception was a rich deposit of fine quality honey and brown colored chert debitage, predominantly tertiary flakes, at the base of the entry stairway to Room C, between the stairs and the southern base of the north tower. Associated ceramics, such as Cedro Gadrooned, Pastelaria Composite, variant Pastelaria, and Encanto Striated, variant Yokat indicated a Terminal Classic affiliation.

South Side Excavations

Sixteen 2 m by 2 m units were excavated on the south side of the structure, revealing evidence of a stairway leading from the plaza to the entry into Rooms A and B (figure 7). No midden deposits were found and artifact recovery varied from a low of 10 sherds in the southeast exterior corner of the structure to a high of over 200 west of the entrance; diagnostics represented types from the Late Preclassic through Terminal Classic periods.

West Wall Excavations

Ten 1 m by 2 m adjacent units were excavated along the west (rear) wall, producing minimal artifacts and no evidence of midden. However, an unslipped, restricted-orifice bowl with an out-flaring rim (cache 1) was found in an inverted position next to the foundation.

Other Excavations on the Exterior

Fourteen randomly selected sample and two judgmentally placed 2 m by 2 m units were excavated to investigate the building perimeter. None yielded structural remains, midden, or noteworthy quantities of artifacts, although evidence of quarrying was identified.

Interior Excavations

Six rooms comprise the interior of 6N-1. Our investigations focused on Rooms A, B, C, and D. Rooms C and D share a common doorway, with the long axes oriented north/south; entry is via the front (east) side of the building (figure 8). The long axes of adjoining Rooms A and B are oriented east/west and accessed from the exterior by a door on the south side. Rooms E and F are also oriented east/west on the north end of the structure. The double set of rooms flanking C and D are nearly identical, except for a small doorway at the north end of Room D that originally led to Room F, but was filled-in (Merwin, 1913), leaving a small alcove in Room D, which was evident at the time of our work. Also, Castillo (1998) reported a subterranean tunnel in Room E that led to a chamber in the north tower; there was no counterpart found in Rooms A or B.

Thirteen sub-floor units were excavated in the structure interior during the 1976 work (figure 9). With the exception of units 1 and 6, the interior excavations were over areas where the plaster floors were completely sealed, affording temporal control and a clear picture of sub-floor construction. Excavation unit 1 was deliberately placed over a plaster patch and uncovered a burial, discussed later along with occupational chronology. In the case of unit 6, which was excavated immediately west of the entryway to Room C, a small area of the plaster was partially broken and it was unclear if the sub-floor deposits there were contaminated.

The ceramics recovered from sealed sub-floor contexts in units 2 to 5 and 7 to 13 included Late Preclassic to Late Classic types. The majority of identifiable ceramics were Late Classic types, notably dominated by Becanchen Brown, variant Becanchen, with lower incidences of types like Achote Black, variant Achote and Tinaja Red, variant Tinaja.

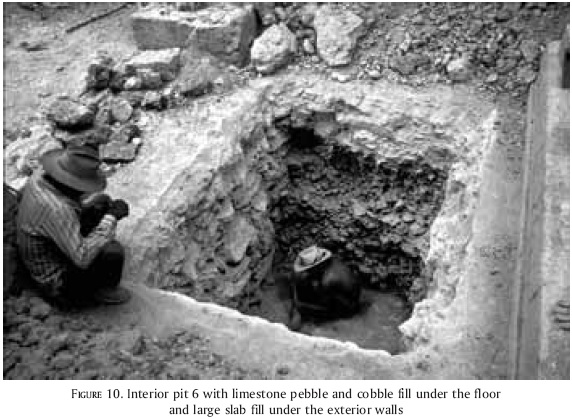

There was no evidence of superimposed floors in any of the 13 interior excavations. Throughout the building, the plaster floors were set on top of a course of large limestone slabs overlying rubble fill. In the rooms where there was no wall to support, the layer of large limestone slabs overlay a fill of small limestone cobbles, and one or more horizontal layers of sascab were used to stabilize and level the fill. For structural support of both exterior and interior walls, the large limestone slabs formed a foundation wall continuing unbroken to bedrock. The contrast in construction technique between structural support walls and non-supporting walls is apparent in the south and east profiles of unit 6 in Room 6 (figure 10).

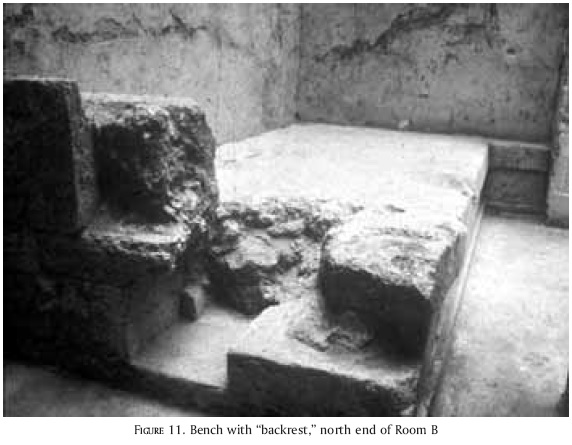

Benches coated with plaster represent original architectural features observed in three of the four rooms. The bench in Room B had a partially intact backrest on the west end where a niche was about 10 cm above the floor (figure 11). Room C had two benches, one at each end of the room, with a small niche in the wall above the south bench (figure 12). Room D was nearly covered by a bench, with a niche on the east side, facing the main entryway (figure 13).

Numerous wall holes were observed in Room A (figure 14). There are two biconically-shaped cord holders flanking the entry doorway on the interior of the room, elevated an average of 50 cm above the floor. Also, four recessed rod holders flanked the interior of the entry door, two located just below the lintel and two elevated less than 50 cm above the floor. All of these holes, presumably for hanging or securing curtains, mats, or some kind of covering over the doorway, were plastered on their interior, indicating that they were installed when the building was erected or at least when the last coat of plaster was applied.

Similar features were observed in Room B, where a single cord holder was set in the door jamb. In Room C a single recessed rod holder was on the north side of the entry way, fifty-eight centimeters above the floor. Other rod holders and cord holders were likely destroyed when the structure collapsed. One biconically shaped cord holder was evident in the north interior door jamb of Room D, elevated 76 cm above the floor. None was apparent in the south jamb, even though it had not collapsed. Also, two recessed rod holders flanked the interior doorway of Room D, 45 and 53 cm above the floor.

Discussion

The 1976 investigations produced a large amount of data, too voluminous and topically varied for a single article. Thus, this discussion considers major findings regarding construction, modification, and temporal use of Structure 6N-1.

Original Construction and Modifications

The sub-floor excavations revealed different methods of construction with regard to load-bearing versus non-load-bearing walls and, importantly, a complete absence of superimposed floors. The latter confirms that Structure 6N-1 was originally constructed as a six-room building, erected from the ground up in one stage of construction. It had a plaza that was two and a half meters wide in front of the east-facing entrance, accessed on the east end by a five-step stairway (Stairway 1). How far the plaza stretched north/south is undetermined.

Merwin (1913) stated that he thought the main part of the building and the towers were built at the same time, albeit noting that the veneer of the bases of the towers did not dovetail with the building, but were simply built against it. We saw a small portion of the exposed wall against which the south tower was set and it was dressed stone. If the entire wall was dressed in this manner, it raised the question why the builders would dress a wall that was immediately going to be concealed by a tower. If the tower was set against the wall at the time of original construction, the wall would probably have been built with undressed stone, a characteristic we observed during earlier excavations at Becan. In addition, the initial plaza and Stairway 1 were part of the original construction, but this plaza was not large enough to accommodate the towers.

On the interior, it appeared that the original east end wall in Rooms A and B was slab masonry of roughly-dressed stones set in mortar with considerable chinking and apparently not covered with plaster. In comparison with the other walls in the structure, this crudeness implies anticipated modification and, in fact, the rooms were subsequently shortened by the addition of rubble fill and the erection of a second wall (figure 15), constructed of more finely cut veneer stones set closely together and covered with a coat of plaster. Since the southern portion of both towers directly overlaid the north end of Rooms A and B, and E and F, it is clear that the shortening of those rooms was designed for solid support for the weight of the tower and was apparently planned for in the original design. This interpretation is supported by Arnauld's (2007) excavations, which exposed the foundation of the north tower and the base of the northern room. The lay out was interpreted as evidence the addition of towers was intended from the very beginning of construction.

Taken together, the data indicate the towers were part of the structural design, but later additions. The dressed stones on the east wall where the towers would eventually abut the building and construction of the original plaza and Stairway 1 gave the pre-tower exterior a finished appearance. Apparently keeping a nice façade outside was important, but the occupants could apparently live with the undressed walls inside until the modifications to shorten Rooms A, B, E and F could be accomplished, the towers erected, the plaza enlarged (covering Stairway 1), and Stairway 2 constructed. Situated as it was, Cache 2 appears to have been an offering placed at the time the plaza was enlarged.

While the timing of these modifications is undetermined with confidence, the data indicate that not much time elapsed between the original construction and modifications, a finding that argues for all stages of construction being the work of the Late Classic people.

Late Classic Occupation

During its heyday, Structure 6N-1 certainly seems to have been the domain of high status nobility. We agree with Michelet et al. (2005) that Structure 6N-1 and 6N-2 probably had complementary functions, but the association is not fully determined. Structure 6N-1 is the more grandiose of the two and has been referred to in the literature repeatedly as a "temple." However, that may be a misnomer as some features of Structure 6N-1 suggest it may have been a private residence that also served public functions.

For example, the features in Rooms A and B seem designed for privacy with the cord holders and curtain supports, strengthening the interpretation of these rooms as probable residential areas. The bench in Room B was more reminiscent of a bed than public sitting area. There was also the niche and a small space between the back of the bench (refer to figure 11) and the west wall, which were not designed to be visible from the outside or from within Room A, so these features appear more likely to have been areas for storing personal items.

Rooms C and D seem designed for creating an imposing atmosphere with greater public exposure, possibly representing the more public area of the building. For example, the elevated bench in Room D is a commanding architectural feature, having taken up most of the space in that room, and the centrally placed niche seems situated for maximum viewing from outside the central entrance on the east side of the building (refer to figure 13). The two benches at either end of Room C may have alternately served as seating or raised platforms. However, there were also cord holders and other holes in the walls and door jambs of Rooms C and D. The presence of these features suggests that even these rooms that face the central entrance could be cordoned off from view to afford the occupants privacy.

By the end of the Late Classic Period, Rio Bec Group B appears to have either lost the status enjoyed in former times or to have been abandoned in favor of a new occupational locale. The rather early and partial collapse or destruction of the central doorway suggests that persons of high status associated with 6N-1 were no longer in residence and/or power.

Terminal Classic Occupation

While there is ample evidence of Terminal Classic occupation at Structure 6N-1, it seems far removed from monumental construction continuing to take place in the region, such as evidenced by the massive twin towered Structure A-1 in Group A (Michelet, 2007) and Structure 1 at Ceibarico (Nondédéo, 2007). Instead, the Terminal Classic presence at Structure 6N-1 was marked by defacing of the building and accompanied by an occupation of the central rooms. Arnauld (2007) noted that six curved stones displaced from the corner of the north tower were in contexts that suggest an episode of ancient pillaging. We uncovered a large segment of the central lintel lying directly on the floor in the doorway between Rooms C and D, amid other rubble from the initial collapse.

Subsequent to the first destructive event, the excavations produced evidence of a second episode of collapse, best illustrated in the profile of a balk left during clearing operations in Room C (figure 16). The first episode is represented by a 20 to 30 cm-thick stratum of gray midden-like soil containing artifacts and mixed with collapsed structural stones. We believe that this lower stratum was formed by the initial stage of collapse and was accompanied by a Terminal Classic occupation in the room. The "midden" deposit yielded Terminal Classic ceramics, including, among others, Altar Fine Orange, Jalapeño Scored, variant Jalapeño, Cedro Gadrooned, and Encanto Striated, variant Yokat, along with chert debitage. A metate found directly on the floor by the main entryway to Room C appears related to this occupation as well (figure 17).

At a later time, a much more substantial collapse occurred as witnessed by a thick stratum of light gray soil with a large amount of rubble, including stones from the vault and roof comb, but in the absence of occupational refuse. Overlying both of these strata is a layer of humus mixed with pebbles, cobbles, and a few larger stones, all of which represent the most recent and continued caving-in of the building.

Whether responsible for the partial collapse of the structure or not, the Terminal Classic occupants of 6N-1 made no attempt to clean rubble from the building, although there is evidence of its use. Besides the aforementioned metate, a crude barrier was fashioned of unmortared limestone slabs atop 20 to 30 cm of midden and rubble from the initial collapse (figure 18). Oriented roughly east/ west, this crude wall extended into the room, effectively subdividing the northern two-thirds of Room C from the remaining area. Three stone-lined hearths associated with this occupation were also found above the intact plaster floor, right on top of and amid the initial layer of rubble.

Unit 1 was laid out in Room D where a small area of the bench had been covered with a patch, on top of which were four stains from incense burning. Excavations extending through the patch encountered a flexed burial (figure 19) of a male, still partially covered with fragments of a woven mat. Ash and charcoal surrounded the skeletal remains. The bones and mat show no evidence of having been exposed to fire, so the ash and charcoal were added to the pit, either before or after the interment occurred.

The individual was buried with three complete pottery vessels and a jadeite bead (figure 20d). Two of the vessels were the Terminal Classic type Torro Gouged Incised (figure 20a and b). The largest was a tripod dish inverted over the man's head. The second was a small vessel laid a few centimeters below the head. The third vessel seems to be an atypical form of Encanto Striated (figure 20c).

The burial from 6N-1 has a remarkable counterpart in an interment (figure 21) from Structure 7N-4 at Group D, located only about 200 m to the south/south-west. According to Pereira (2007), the latter burial was under a patch in the floor. As was the case with the burial at 6N-1, two Torro Gouged Incised vessels accompanied the burial, one of which was a tripod dish inverted on the head. The similarity between the two burials is striking. It is obvious these two burials are contemporaneous and, if not of related individuals, certainly ones with similar spiritual values.

Elsewhere in the Rio Bec region, Torro Gouged Incised tripod dishes and restricted orifice vases were recovered from Terminal Classic burials at Becan and Hormiguero, the latter from tailings of a looter's pit (Ball, 1977). These data suggest the use of these ceramic types as funerary accompaniments was common in the Rio Bec region at the time.

Besides the stains on the floor patch in Room D, mentioned above, circular stains of varying size covered the bench and a few were found on the floor adjacent to the bench. However, none were on the floor within the central part of Room C and the eastern part of the doorway into Room D, where the greatest amount of debris related to the initial collapse occurred. All but one of the incense stains in Room C (figure 22) were on the benches at either end of the room where the vaults remained intact during the Terminal Classic occupation. Very little debris from the initial collapse extended into Room D, and the circular stains occur throughout the room, with most near the side walls. Several stains were also in Rooms A and B, where there was no clear evidence of Terminal Classic occupation, so the affiliation of these episodes of burning is unclear. Within Rooms C and D, however, the combined data suggest the Terminal Classic occupation began after portions of 6N-1 had fallen.

Finally, there is the heavy deposit of fine honey to brown colored chert debitage found just outside the building at the base of the stairs to Room C, between the stairs and north tower. Rovner (1975) writes about the use of a high quality honey-brown to clear dark brown chert, probably from Quintana Roo or British Honduras, was a defining characteristic of the Late Classic Chintok phase at Becan and continued into the Terminal and Early Postclassic periods. At Structure 6N-1, the honey to brown colored chert is associated with the Terminal Classic activity.

Termination Rituals

At the time of our 1976 investigations at Structure 6N-1 the concept of Termination Rituals was not yet in vogue, and we considered the final episode of occupation at the structure to be just that, an occupation, albeit of squatters. In 2007, it seems appropriate to raise the question as to whether the Terminal Classic materials from the structure represent a Termination Ritual. On the one hand, arguments in favor of that interpretation can be made based on what appears to have been destruction to the entryway and north tower. The numerous stains caused by the burning of incense certainly point to ritual activities. On the other hand, the presence of the hearths, the 20 to 30 cm thick midden mixed with the rubble and the crude unmortared barrier argue for an actual Terminal Classic occupation. In addition, if there had been a Termination Ritual, the burial seems out of place in a building that had been ritually closed out.

The duration of the Terminal Classic stay is undetermined, but was probably not long. It may have ended with or shortly after the death of the male individual interred in Room D. Whatever the length of occupation, once this group departed, Structure 6N-1 was completely abandoned.

Consideration of the Late Classic and Terminal Classic Settlement at Rio Bec

The 1976 investigations recovered important data on the Late Classic construction, occupation, and modification of Structure 6N-1, and revealed episodes of destruction as well as a Terminal Classic occupation. The issues of function and settlement dynamics remain under the microscope in terms of investigations in the Rio Bec region. As we have noted, structures like 6N-1, with its monumental twin-towered construction, had earlier been interpreted solely as public places, and even referred to as "temples." There is nothing to dispute the idea fostered by Michelet et al. (2005) that Structures 6N-1 and 6N-2 were seats of power and they may have served political, social, and/or ritual purposes. At the same time, there is evidence supporting a residential function of 6N-1 and 6N-2 as well. The variable size and opulence of design between buildings within the group may have had as much to do with the status and wealth of the owner as it did with function.

It is particularly difficult to reconcile the demise of Group B contemporaneously with evidence of population continuity at other locations, such as the aforementioned Group A (Michelet, 2007). The relationship of Group B to Terminal Classic settlement dynamics in the Rio Bec region is another unresolved issue, especially in light of the shared cultural traits implied by the stark simi-larities between the burial at 6N-1 and that found in Structure 7N-4 at Group D (Pereira, 2007). Whatever prompted the apparently intentional effort to deface part of Structure 6N-1, it is clear that societal disruptions were occurring in the Rio Bec area at the end of the Late Classic period, but these events were not manifested uniformly throughout the sub-region.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnauld, Charlotte, 2007 "Operación VB", Río Bec (Campeche, México). Informe de la quinta temporada del 5 de febrero al 4 de mayo de 2006, pp. 75-109. Mexico, Paris: CNRS Archéologie des Amériques (UMR 8096) / Archivo Técnico del INAH, Centro INAH Campeche. [ Links ]

Ball, Joseph W., 1977 The archaeological ceramics of Becan, Campeche, Mexico. New Orleans: National Geographic Society / Tulane University Program of Research in Campeche (Middle American Research Institute, 43). [ Links ]

Carrasco, Ramón, Sylviane Boucher and Agustín Peña, 1986 "Río Bec: un modelo representativo del patrón de asentamiento regional", Boletín de la Escuela de Ciencias Antropológicas de la Universidad de Yucatán, 14 (78): 20-29. Merida: Universidad de Yucatán. [ Links ]

Dzul, Sara G., 2007 "Análisis de la Cerámica", Río Bec (Campeche, México). Informe de la quinta temporada del 5 de febrero al 4 de mayo de 2006, pp. 12-16. Mexico, Paris: CNRS Laboratoire Archéologie des Amériques (UMR 8096) / Archivo Técnico del INAH, Centro INAH Campeche. [ Links ]

Hay, C.L., 1935 "A contribution to Maya architecture". Natural History, 36 (1): 29-33. New York: American Museum of Natural History. [ Links ]

Merwin, R.E., 1913 "The ruins of the southern part of the peninsula of Yucatan". Ph.D. thesis, Cambridge [Massachusetts]: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Michelet, Dominique, 2007 "Operación VA: estructura principal del Grupo A", Río Bec (Campeche, México). Informe de la quinta temporada del 5 de febrero al 4 de mayo de 2006, pp. 73-94. Mexico, Paris: CNRS Laboratoire Archéologie des Amériques UMR 8096) / Archivo Técnico del INAH, Centro INAH Campeche. [ Links ]

Michelet, Dominique, et al., 2007 Río Bec (Campeche, México). Informe de la quinta temporada del 5 de febrero al 4 de mayo de 2006. Mexico, Paris: CNRS Laboratoire Archéologie des Amériques (UMR 8096) / Archivo Técnico del INAH, Centro INAH Campeche. [ Links ]

Michelet, Dominique et al., 2005 "Río Bec, ¿una excepción?", Arqueología Mexicana, XIII (75): 58-63. México: INAH, Raíces. [ Links ]

Nondédéo, Philippe, 2007 "Operación III: reconocimiento micro-regional (6 de febrero-3 de abril)", Río Bec (Campeche, México). Informe de la quinta temporada del 5 de febrero al 4 de mayo de 2006, pp. 23-58. Mexico, Paris: CNRS Laboratoire Archéologie des Amériques (UMR 8096) / Archivo Técnico del INAH, Centro INAH Campeche. [ Links ]

Nondédéo, Philippe et al., 2003 "Río Bec: primeros pasos de una nueva investigación". Mexicon, XXV (4): 100-105. Markt Schwaben [Germany]: Verlag Anton Saurwein. [ Links ]

Peña Castillo, Agustín, 1998 "El Templo B de Rio Bec. Montaña viviente y acceso al inframundo", Gaceta Universitaria, VIII (39-40): 34-41. Campeche: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche. [ Links ]

Pereira, Gregory, 2007 "Operación VI: prácticas funerarias", Río Bec (Campeche, México) Informe de la quinta temporada del 5 de febrero al 4 de mayo de 2006, pp. 139-148. Mexico, Paris: CNRS Laboratoire Archéologie des Amériques (UMR 8096) / Archivo Técnico del INAH, Centro INAH Campeche. [ Links ]

Perigny, Maurice de, 1908 "Yucatan inconnu", Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris, (5): 67-84. Paris: Journal Sociètès des Américanistes de Paris. [ Links ]

Rovner, Iwin, 1975 "Implications of the lithic analysis at Becan", Preliminary Reports on Archeological Investigations in the Rio Bec Area, Campeche, Mexico, pp. 128-132, Richard E.W. Adams (comp.). New Orleans: Tulane University (Middle American Research Institute Publication, 31). [ Links ]

Ruppert, Karl and John H. Denison, Jr., 1943 Archaeological Reconnaissance in Campeche, Quintana Roo & Peten. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington (Publication, 543). [ Links ]

1 Unless specified, all figures are part of the 1976 project documentation.

2 When the 1976 investigations were undertaken, Structure 6N-1 was called "Temple B". This document uses the current redesignation from Nondédéo et al. (2003).

3 Some excavation units were smaller or irregular due to proximity to the structure and other factors.

Infromación sobre los autores

Prentice M. Thomas. Estadounidense. Doctor en Antropología por la Universidad de Tulane. Presidente de Prentice Thomas & Associates, Inc., consultores en arqueología, con base en la ciudad de Mary Esther, Florida. Bajo el patrocinio de la National Geographic Society realizó estudios en la ciudad de Becán, Campeche. Profesor en la Facultad de Antropología de la Universidad de las Americas, Cholula, Puebla. Director de las excavaciones y consolidación de la Estructura 6N-1 de Río Bec.

L. Janice Campbell. Estadounidense. Maestra en antropología por la Universidad de Tennessee. Vicepresidenta de Prentice Thomas & Associates, consultores en arqueología, con base en Mary Esther, Florida. Junto con Prentice Thomas excavó y consolidó la Estructura 6N-1 de Río Bec.