The Spanish Crown employed the institution of the mission in an effort to integrate indigenous peoples on the frontiers of the Americas into colonial society. The origins of the mission went back to the first evangelization campaigns among the sedentary peoples of the first territories the Spanish subjugated, such as in central Mexico following the arrival of the first group of Franciscans there in 1524. Missionaries from different religious orders established doctrinas (missions) in the most important towns, and organized the missions based on the existing political structure. This pattern of reliance on missions, however, began to change when the Bourbon dynasty assumed power in Spain following the death of the last Hapsburg Carlos II in 1700. The Bourbon monarchs of French descent began tinkering with the Hapsburg colonial system in the first half of the eighteenth century. They wanted to enhance royal authority and rationalize the inefficient and decentralized Hapsburg colonial system that had its origins in late medieval notions of political and economic organization.

The reorganization in 1744 of the Sierra Gorda missions (Querétaro) by Colonel José de Escandón y Helguera, who the Crown had commissioned to create the Colony of Nuevo Santander in northeastern New Spain, was an example of the early reform impulse during a period in which royal officials tinkered with the colonial system they inherited from the Hapsburgs. The Sierra Gorda formed a part of his jurisdiction, and following his inspection of the Augustinian, Dominican, and Jesuit missions in the region he petitioned the Viceroy to remove the Augustinians. Escandón assigned Franciscans from the Apostolic College of San Fernando (Mexico City) to staff the reformed missions. Two decades later this same group of Franciscans played an important role in the implementation of the new mission model in the Californias.1 However, the reform impulse accelerated following military defeat in the Seven Years War (1755-1763), and the implementation of military, administrative, and fiscal reforms designed to strengthen colonial defenses and increase taxes to pay the costs of a new colonial army.

King Carlos III (r. 1759-1788) sent his loyal servant José de Gálvez y Gallardo (1720-1787) to New Spain in 1765 with extensive powers to implement reforms as he saw fit. Gálvez was a key architect of reform and in 1776 became the Minister of the Indies responsible for governing the Americas. He oversaw the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 and the reorganization of frontier missions along the lines of making them cost-effective and as self-sufficient as possible. This he accomplished in Baja California in 1768 following the expulsion of the Jesuits, and he had the Jesuits replaced there by the Franciscans from the Apostolic College of San Fernando who had already collaborated with Escandón in the reform of the Sierra Gorda mission. In 1769, Gálvez worked with Junípero Serra, OFM, the Father-President of the Baja California missions and a veteran of those in the Sierra Gorda, to plan the occupation of Alta California. Gálvez’s plans and expectations for the new missions were codified in a set of rules (reglamento).2 Above all other things, the missions were to be economically self-sufficient and not be a drain on royal finances, and were to accelerate the process of integration of indigenous peoples into colonial society. The plan for the Alta California missions reflected the fullest development of the reform initiative for frontier missions. As they had done in the Sierra Gorda and Baja California following the Jesuit expulsion, the Franciscans from the Apostolic College of San Fernando were handmaidens to Gálvez, and other reform-minded civil and military officials, and implemented the changes in the mission program that they wanted. The Alta California mission model as implemented by Serra and his colleagues also represented the worst-case scenario in terms of its effects and particularly the demographic effects on the indigenous populations brought to live on the missions, as seen in a case study of the missions among the groups collectively known today as the Chumash. Integration meant conformity to European norms of sexuality and family life. The indigenous populations were to be congregated in new communities organized on the grid plan as stipulated by Crown law and live in European-style housing. They were to become a disciplined labor force in an economy based on agriculture, ranching, and pay tribute. Neophytes were to dress decently and speak Spanish, among other changes expected in cultural norms.

The events that lead to the 1760s reform initiatives began earlier in the Caribbean Basin. Spanish colonial commerce passed through the region, and the flotas (convoys of merchant ships protected by warships) became the target of Spain’s European rivals and the buccaneers, a conglomeration of people of different nationalities that engaged in piracy.3 Spain responded to the threat to its commerce by building massive stone fortifications to protect its ports, a strategy that proved flawed when the British occupied Havana and Manila in 1762 during the Seven Years War.4 A failed British assault on Cartagena in 1741 had temporarily reaffirmed Spanish confidence in this defensive strategy, but it was illness rather than Spanish defenses that defeated the British attack (see Plate 1).5 The Spanish defeat at the hands of the British in the Seven Years War (see Plates 2-3) resulted in a military reorganization in Spanish America soon after the end of hostilities. The military reform led to the creation of the first standing armies in Spanish America, and the challenge was to fund the new army. The military reorganization was a key element of the so-called Bourbon Reforms in Spanish America after 1762.6 Administrative reform attempted to make the collection of taxes more efficient, and the Bourbons also promoted the economic development of some regions with the objective of being able to collect more taxes.

The Library of Congress, Washington, D. C.

Plate 3 A contemporary map of the 1762 British assault on Manila.

The Reform of the Sierra Gorda Missions

Influenced by Enlightenment ideas, increasingly anticlerical royal officials began to question the role of the Catholic Church in the economy and politics and criticized the institution of the mission as retarding the integration of natives into colonial society. The reorganization of the Sierra Gorda was one of the first instances of the implementation of Bourbon reform ideas on frontier missions. The evangelization of the Sierra Gorda began in the 1530s and 1540s and continued up until the end of the Colonial period in the early nineteenth century. Despite efforts to change their way of life, the Pames and Jonaces frequently resisted or at best settled on missions only for short periods of time. As already noted, the Crown commissioned José de Escandón to colonize the region in northeastern New Spain that he called Nuevo Santander that included the Sierra Gorda, and he implemented reforms designed to accelerate and complete the process of the integration of the Pames and Jonaces that inhabited the region. In a detailed report drafted in 1743, Escandón strongly criticized what he saw as the failure of some 200 years of Augustinian evangelization in the region. He decided to assign Franciscans from the apostolic colleges of San Fernando (Mexico City) and Pachuca to the missions with a mandate to get the job of integration done.7

The Augustinian responses to Escandón’s report provide a clear picture of the status of evangelization efforts at the point of the transfer of the Augustinian missions to the Franciscans, and of the conditions that convinced Escandón of the need for reform. In a letter directed to Escandón, Lucas Cabeza de Vaca, OSA, the last Augustinian stationed on the mission at Xalpa (Jalpan de Serra, Querétaro), identified the pattern of Pames resistance to evangelization. He noted that many Pames did not come to catechism or mass, and that non-attendance was particularly a problem at the visitas of Pisquintla and Amatlán. Moreover, Pames continued to stage ritual dances at which they consumed wine and tepache (a fermented alcoholic beverage). Cabeza de Vaca suggested that two or three soldiers should be stationed at Xalpa to help force the Pames to congregate on the mission.8

José Francisco de Landa wrote the official Augustinian response to Escandón’s 1743 report. De Landa’s document echoed the frustration of the Augustinian, and conflicts between the missionaries and Spanish settlers, and particularly hacienda owners. José de Landa highlighted problems with two hacienda owners. The first was Cayetano de la Barreda, who also held the title of protector de indios (protector of the Indians). The Augustinians claimed that Barreda had not supported their mission, and also noted that he had some 300 mules pastured on mission land at Pacula. The report further claimed that the Jonaces who lived at Pacula returned to the mountains because Spaniards had usurped their lands. Moreover, José de Landa complained that Barreda provided soldiers to help the Franciscans force Jonaces to settle on Vizarrón, but did not provide the same assistance to the Augustinians.9 The second hacienda owner was Gaspar Fernández de la Rama, who owned the trapiche (sugar mill) and hacienda at Concá, close to the visita of Xalpa mission. De la Rama reportedly employed Pames, and provided his workers with alcohol. José De Landa’s report also alleged that De la Rama forced natives to work on his mill and hacienda.10

The report also challenged Escandón’s contention that the Augustinians had failed to teach the Pames and Jonaces Catholic doctrine. The report charged that the Jonaces living on the Dominican missions of San Miguelito and Soriano, the Franciscan missions San José de Vizarrón, San Pedro Tolimán, San Juan Bautista Xichú de Indios, and the Jesuit mission San Luis de la Paz also did not know doctrine.11 As the report emphasized, “…the Indians that don’t know the doctrine are the mecos that are dispersed throughout the mountains”.12 However, the defensive tone of José de Landa’s report and the finger-pointing masked the reality that the Pames and Jonaces resisted the mission program of directed social change and evangelization regardless of the order that supplied missionaries, and preferred to live on small settlements in the mountains. José de Escandón sent soldiers to try to force the Pames and Jonaces to settle on the missions, but many reportedly did not want to, and did not want to learn doctrine nor have their children catechized.13 However, once the Franciscans established the five missions, they resettled thousands of Pames with support from the military. Local officials sent soldiers to the mountains to burn the residences of the Pames to pressure them to relocate to the mission communities. The use of the military to congregate and impose social controls was an innovation from earlier practices in the region and was more fully developed on the California missions.

Escandón’s critique of the Augustinians called for a new approach to evangelization that implied greater social control of the Pames and Jonaces, as well as an effective congregation of the populations on the mission communities. Escandón gave the Franciscans from the Apostolic College of San Fernando jurisdiction over the Augustinian mission at Xalpa and the visitas at Tancoyol and Concá, and ordered the establishment of new missions at Landa and Tilaco. The Franciscans congregated thousands of Pames on the new and reorganized missions. A census prepared in 1744 enumerated 3 767 Pames congregated on the five missions, with the largest number settled on Xalpa.14 The handful of existing reports on the missions provide clues to the methods used, methods that the same group of Franciscans later employed when they assumed responsibility for the former Jesuit missions in Baja California in 1768 and on the California missions established after 1769. The Franciscans placed greater emphasis on promoting the economic dependence of the Pames and Jonaces, which was also seen as the key to keeping the natives congregated on the missions. The Franciscans attempted to transform the natives into sedentary agriculturalists and required them to work on communal projects that included agriculture, tending livestock, and building projects. Moreover, the Franciscans assigned the individual heads of household individual subsistence plots where they reportedly grew corn and frijol for their own subsistence.15 The Franciscans had communal crops stored in a granary under their control and distributed a daily food ration.16 The purpose of the food ration was to prevent the Pames from leaving in search of food and to enhance economic dependence on the missions.

The Jesuit Expulsion and Mission Reform

In 1767, two decades following the establishment of the Sierra Gorda missions, King Carlos III ordered the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spanish territory. In the wake of the expulsion, royal officials imposed a new form of administration in line with the Bourbon reform initiative. In the ex-Jesuit missions among the Guaraní in the Río de la Plata region of South America (parts of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay) royal officials appointed civil administrators with a mandate to have the mission residents generate income to pay the costs of administration such as the salaries of the administrators and the priests who replaced the Jesuits, and tribute payments. Royal officials administered the mission communal economies to generate income. The Franciscan, Dominican, and Mercedarian missionaries who replaced the Jesuits, however, did not exercise the same control over the communal mission economies as the Jesuits had. This policy responded to the Bourbon reform initiative to streamline the costs of administration and produce income to help cover the costs of the military reform in the Americas. The Franciscans who replaced the Jesuits in Baja California initially operated under a similar system in which they did not control the mission economies. It also generated considerable paperwork required to document the costs of administration. The increase in economic activity in the region also contributed to an exodus from the missions of mostly men and older boys who sought to work and live outside of the missions.17

The record of efforts to produce income to cover costs on Los Santos Mártires mission was typical. The civil administrators of Los Santos Mártires sought to find products to sell to generate income. The implementation of the so-called “comercio libre”, or freer trade within the Spanish trading system, created new opportunities for the Río de la Plata region. One such opportunity was the export of hides and tallow from Buenos Aires to Spain. The Jesuits also maintained herds of cattle and other livestock on estancias (ranches) located in the banda oriental (modern Uruguay and Rio Grande do Sul). The estancia of Yapeyú measured some 50 × 30 leagues or some 47 000 square kilometers.18 The Jesuits stationed on Los Santos Mártires operated two estancias named Santa María and San Gerónimo. The 1768 inventory prepared in the wake of the Jesuit expulsion described both ranches. They had chapels and other improvements described in different terms such as paraje and rodeo. Improvements included the chapels, corrals, and barracks for the Guaraní workers assigned to the estancias, and store-rooms.19 Los Santos Mártires was not a major cattle producer, and other missions specialized in ranching. Hide exports totaled 177 656 in the years 1768 to 1771 and increased to 1 258 008 in the years 1777 to 1784.20 Yapeyú mission was a major producer of hides, and civil administrators had the mission herds culled for hides and tallow. The large-scale slaughter of cattle was reflected in drops in the number of animals reported in mission inventories.21 The civil administrators of Los Santos Mártires mission chose cotton and cotton textiles as the income producer. They rapidly expanded the number of cotton plants grown at the mission in the 1770s, and in 1785 an inventory reported a total of 584 000 plants.22

Inventories prepared at the direction of the civil administrators of Los Santos Mártires mission recorded the numbers of livestock that belonged to the mission (see Table 1). The number of cattle fluctuated but did not evidence declines on the same scale, for example, as at Yapeyú where the civil administrators ordered the large-scale slaughter of cattle for hides and the production of tallow. That is not to say that the civil administrators of Los Santos Mártires did not have cattle hides cured. An 1804 document listed the skilled jobs at the mission and of the individuals who held the title of “maestro” (master). That is the person that directed that particular activity. There was a “maestro curtidor” (master curer) responsible for the curing of cattle hides.23 A 1795 account recorded several entries with quantities of hides. One was for 3 523 hides taken from cattle slaughtered over time for the consumption of beef and another 651 hides from other sources for a total of 4 174. The same account recorded the use of 2 363 hides to cover expenses, 920 hides used to pay a debt, 320 to pay for goods for the community, 11 for employees, and other uses. Altogether, the civil administrator used 4 136 of the hides in administrative costs, which left 48.24 At the same time, the civil administrators replenished the mission herds. One transaction in 1770 involved the purchase of 1 000 head of cattle from Yapeyú paid for with yerba mate.25

Table 1 Livestock reported on Los Santos Mártires Mission

| Year | Cattle | Oxen | Sheep | Horses | Burros | Mules |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1768 | 8 977 | 1 779 | 10 760 | 1 653 | 191 | 310 |

| 1785 | 10 615 | 729 | 1 218 | 2 706 | 137 | 408 |

| 1786 | 9 974 | 85 | 224 | 5 977 | 57 | ? |

| 1797 | 9 895 | 480 | 138 | 6 247 | 109 | 10 |

| 1798 | 9 966 | 487 | 96 | 6 754 | 96 | 18 |

| 1801 | 10 119 | 467 | 42 | 4 850 | 84 | 75 |

Source: Robert H. Jackson, Demographic Change and Ethnic Survival Among the Sedentary Populations on the Jesuit Mission Frontiers of Spanish South America, 1609-1803: The Formation and Persistence of Mission Communities in a Comparative Context (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 170-171, note 18.

The civil administrators of Los Santos Mártires organized a type of “putting out” system for the production of textiles made from both cotton and wool. The same 1804 document cited above listed a master weaver (maestro tejedor) who would have been responsible for overseeing the production of cotton and wool textiles and yarn or thread.26 A 1790 accounting, for example, recorded the distribution of cotton and wool to weavers, and the production of textiles. The accounting contains different categories of information such as the amount of wool and yarn given to the weavers (Partidas de Lana repartidas para las ilanzas de este Pueblo), the distribution of cotton (Partidas de Algodon destinadas para las ilanzas de este Pueblo en las tareas que se andar repartir a las chinas), or figures on production (Lienzos Fabricados con el Ylo dado a los Texedores como consta en este Diario) that reported three grades of textiles classified as crude, middle grade, and fine.27 The document provides clues as to the organization of production, but not the total amount produced.

One partial accounting recorded the distribution of 403 arrobas, 11 libras (lbs), 6 onzas (ounces) (4 659.3 kilos) of cotton. A second partial accounting noted the distribution of 139 arrobas, 11 libras, 3 onzas (1 622.9 kilos) of cude (grueso) cloth, and 9 arrobas, 10 libras, 11 onzas (127 kilos) of middle grade (mediano) cloth. Cloth received totaled 142 arrobas, 17 libras (1 670.4 kilos) of crude grade cloth, 10 arrobas, 19 libras, 15 onzas (158.9 kilos) of middle grade cloth, and 7 onzas (0.96 kilo) of fine grade cloth. Individual entries recorded the distribution of small and larger quantities of cotton and wool, and the delivery of finished cloth. One entry, for example, reported the delivery of a length of cloth that measured 106 and a half varas (89 meters), and a second that measured 255 and a half varas (214 meters). A more detailed accounting from 1794 provided a global figure for cotton. The civil administrators bought 512 arrobas, 21 lbs, 8 ounces (5 935.3 kilos) of cotton, had 851 arrobas, 1 lb, 11 ounces from the harvest warehoused, and received another 267 arrobas, 6 lbs. Altogether there was a supply of 1 627 arrobas, 16 lb of cotton (18 745.7 kilos), of which 1 145 arrobas, 6 lb, 2 ounces (13 183.7 kilos) was in the hands of the weavers to be woven into cloth.28

Increased economic activity and regional trade had demograhic consequences for the mission populations, as seen in the example of Yapeyú mission. A continuous record of baptisms and burials between 1723 and 1754 shows that the Jesuits baptized 12 886 as against 8 545, and the population grew from 4 352 in 1723 to 7 997 in 1756. In eight years between 1756 and 1767 for which there is a record, the Jesuits baptized another 3 421 as against 3 124 burials, a net difference of 297. The population totaled 7 974 in 1767 and 8 510 in 1768.29 The last severe epidemic at Yapeyú was a 1718-1719 smallpox outbreak. The mission population dropped from 2 873 in 1717 to 1871 in 1719, and suffered a net decline of some 1 000. Following the Jesuit expulsion, the mission had a population that was extremely vulnerable to smallpox. It had been two generations or a total of 49 years since the last catastrophic smallpox outbreak on the mission in 1718. Two generations had grown with little or no exposure to the malady. The result was a particularly catastrophic epidemic in 1770-1772 that killed some 5 000 Guaraní or a crude death rate in excess of 600 per thousand population or some 60 percent of the population. The mission population dropped from 8 510 reported in 1768 to 3 322 four years later.30 The population recovered following the epidemic and increased to 4 739 reported in 1784 and 5 170 in 1793. There is a record of a second epidemic during the period of civil administration. Burials totaled 777 in 1797 (crude death rate of 172.3). This was the highest death rate on the ex-missions for which there is a record.31 The population dropped to 3 990 at the end of 1797 but then increased again to 4 095 in 1799 and 4 669 in 1802.32

Royal officials also attempted to implement the reform of the ex-Jesuit missions in Baja California. Because of limitations to agricultural production in the most arid Peninsula, the Jesuits had implemented a dispersed settlement pattern on the Baja California missions. Most neophytes did not live congregated in the main mission community. When the Franciscans from the Apostolic College of San Fernando arrived to replace the Jesuits, they did not have control over the mission temporalities, the economic aspects of the mission communities, as was also the case in the missions among the Guaraní. However, on his arrival in the peninsula José de Gálvez reversed the policy and granted the Franciscans control over the temporalities. He also decided that the Franciscans were to also control the temporalities of the new missions to be established further north in what was to become Alta California.33 Two reforms implemented by José de Gálvez following the Jesuit expulsion accelerated the cycle of demographic collapse on the peninsula missions. The first was the shifting of population between missions to increase the labor available at missions with greater agricultural potential.34 This was an effort to make the missions as self-sufficient as possible in line with the Bourbon initiative to make colonial administration cost-effective and was similar in intent to the policies of the civil administration on the ex-Jesuit missions in South America. Gálvez had people transferred from San Francisco Xavier to Loreto and San José del Cabo, and from Guadalupe to La Purísima and Comondú. He also ordered the suppression of Dolores and San Luis Gonzaga missions, and the transfer of the Guaycuros from these two missions to Todos Santos mission which had greater agricultural potential but only a small native population. The Guaycuros had experienced minimal change in their way of life under the Jesuits, but Gálvez expected them to become a disciplined agricultural labor force overnight. The Guaycuros resisted the imposition of a new labor regime, and Gálvez ended up hiring non-indigenous laborers to work the Todos Santos lands. The second was the colonization of Alta California in 1769 which required the movement of more people from the mainland through the peninsula that resulted in the spread of contagion. One contemporary account, for example, noted that a group of colonists bound for Alta California in early 1781 from the mainland to colonize Los Ángeles in Alta California carried smallpox into the peninsula.35 With the increased movement of people disease spread through the missions between 1769 and 1781-1782, killing hundreds.

Records from several of the Baja California missions indicate that mortality reached catastrophic levels during epidemics in 1769 and 1781-1782. At the same time, a contemporary account reported that during the 1781-1782 smallpox outbreak three Dominican missionaries practiced inoculation by variolation, the introduction of pus from a pustule of a smallpox victim into the body of a healthy individual, and reduced death rates. Doctors in Mexico City first used the procedure in 1779.36 Measles spread through the missions in 1769. The Franciscans at Comondú recorded 160 deaths during the year. This was a crude death rate (CDR) of 484.9 per thousand population, and the CDR at Mulegé reached 269.4 per thousand population. Small-pox killed hundreds on the missions in 1781 and 1782, although three Dominicans inoculated the indigenous population and thus reduced mortality. This was at San Ignacio, San Francisco de Borja, and San Fernando missions. On the other hand, mortality was high at other missions. A total of 296 died at Santa Gertrudis from smallpox, 59 at Comondú, and 58 at Mulegé. I have estimated the population of selected missions in 1780 and use this to calculate the crude birth and death rates (CDR). The crude birth rate was low at Mulegé, Comondú, and la Purísima Concepción as a consequence of smallpox, and death rates high. In contrast birth rates at San Ignacio, San Francisco de Borja, and San Fernando did not evidence a similar drop. Mortality reached catastrophic levels at several missions including la Purísima Concepción (CDR of 460.1), Santa Gertrudis (CDR of 422.9 per thousand population), Mulegé (CDR of 362.5 per thousand population), and Comondú (CDR of 361.9 per thousand population). The levels of catastrophic mortality on the Baja California missions were similar to those of the lethal 1737-1740 smallpox epidemic on the Jesuit missions among the Guaraní in the Río de la Plata region that in some instances reached more than 50 percent of the population of individual missions.

The new mission model on the California missions

While Gálvez granted the Franciscans control over the mission temporalities, there were conflicts between Father-President Junípero Serra and the civil authority. In 1772, Serra went to Mexico City to appeal to the Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa (1771-1779). The encounter resulted in the drafting and approval of a set of rules for the missions and military the so-called Echeveste Reglamento drafted by Juan José de Echeveste. The Viceroy rejected another plan being discussed by royal officials which was to strip the missionaries of control over the temporalities and relegate them to the status of mere parish priests. The set of rules regulated the supply and cost of goods shipped to California for the soldiers stationed on the presidios, and plans for the integration of the neophytes who were to become a disciplined agricultural labor force and to produce surpluses to help subsidize the costs of the military in the four presidios established in the province and the escoltas or soldiers posted to each mission to protect and the missionaries and help impose discipline on the neophytes. The reglamento also established that the escoltas were to be controlled by the missionaries.37 The imposition of social control by the Franciscans to maintain labor discipline and compliance with the new social norms paralleled the approach they had earlier used in the Sierra Gorda, but was more fully developed on the California missions.

At the same time, there were instances of conflict between the Franciscans and military officials in California. Two California governors Felipe de Neve y Padilla (1724-1784, gov. 1777-1782) and Pedro Fages Beleta (1734-1794, gov. 1770-1774,1782-1791) attempted to impose their notion of civil authority over the missions but clashed with the Franciscan leaders Junípero Serra, OFM, and his successor as Father-President Fermín Francisco de Lasuén, OFM, who successfully appealed to royal officials to reverse the rules. In 1779, for example, Felipe de Neve y Padilla mandated a rule to create an indigenous government on the missions based on the Iberian municipal government model, which was a measure the missionaries effectively obstructed, and in 1781 rules to impose greater civil control over the Franciscans. In 1787, Pedro Fages Beleta decreed rules to govern relations between the local indigenous populations and settlers, and had earlier written to the audiencia to complain about the behavior of the Franciscans and their administration of the missions. The audiencia backed the Franciscans, and in 1787, King Carlos III repealed the 1781 regulation on the Franciscan missionaries and directed civil officials to support the Franciscan mission effort that in effect gave the Franciscans control over the mission program. In a recent study, Jeremiah Sladek argued that the effort by the two governors to impose civil control over the Franciscans reflected the spirit of the Bourbon reforms, and the decisions by the audiencia and King Carlos III represented the end of the reform initiative on the missions.38 However, the Franciscans fully implemented the main thrust of Gálvez’s plan to accelerate the integration of the indigenous populations into colonial society along the lines of European cultural norms. This included the construction of European-style neophyte housing on a scale not previously seen on missions on the northern frontier of New Spain, with the exception of the unique case of the Texas missions.

The ideal of congregation

In his 1743 report on the Sierra Gorda missions, José de Escandón criticized the Augustinians for having failed to congregate the Pames population on the missions and assigned soldiers to force the Pames to relocate. Similarly, José de Gálvez ordered the shifting of population in Baja California to missions with greater agricultural potential. He had the Guaycuros from Dolores del Sur and San Luis Gonzaga relocated to Todos Santos and expected them to become a disciplined labor force overnight. As already noted, the Jesuits had left the bulk of the Guaycuros population dispersed in their own settlements because mission agriculture could not produce enough food to be able to congregate the entire population on the mission, which was similar to the situation at San Diego mission in the 1770s and 1780s. The order to relocate the Guaycuros to Todos Santos attempted to radically change their work habits and gender division of labor, and they resisted change.

The Spanish policy objective was to create stable sedentary indigenous communities, but this goal often could not be achieved because of limitations to agriculture because of inadequate rainfall as in the case of the Baja California missions. The Jesuit missions among the Guaraní, on the other hand, were an example of the successful congregation of the indigenous populations. The Jesuits created new communities after 1609 and brought thousands of Guaraní to live in the communities.39 In the first half of the seventeenth century the missions had open populations, which meant that the populations expanded through natural reproduction but also from the settlement of non-Christians. The Jesuits baptized both adults and children. As the missions matured the populations became largely closed populations, which meant that there were not significant numbers of non-Christians resettled on the missions, and growth occurred mostly through natural reproduction. However, the Jesuits did periodically settle small numbers of non-Christians at the end of the seventeenth century and the early eighteenth. The 1691 and 1702 censuses, for example, contained a column for baptisms of adults, and the Jesuits reported small numbers of baptisms of adults at several missions.40 In 1691, the Jesuits reported the baptism of seven adults at Candelaria, 11 at Jesús, and ten at Jesús María de los Guenoas. There was a larger number in 1702 with two at Ytapúa, four at Jesús, one at San José, three at Santa Ana, ten at Loreto, seven at San Ignacio, and 46 at Corpus Christi. Corpus Christi was on the frontier, and the Jesuits settled small numbers of Guañanas that lived to the north in the territory between the Paraná and Uruguay rivers. A detailed 1759 tribute census reported 112 Guañanas that had been resettled on the mission in 1724, 1730, and 1754. They were organized politically into separate cacicazgos, but there was intermarriage with the Guaraní population of the mission.41 By congregating the Guaraní on the missions the Jesuits were able to supervise them more closely, and particularly to make sure that the natives did not covertly practice their traditional religious beliefs. However, congregation also had demographic consequences as was also the case on the Sierra Gorda missions. Epidemics of highly contagious crowd diseases such as smallpox and measles spread about once a generation to the missions from surrounding communities along the river highways in the region, and thousands of Guaraní died during these outbreaks.42 A series of epidemics in the 1730s exacerbated by several years of famine conditions resulted in the death of more than 90 000 Guarani.

Rafael Verger, OFM, the Guardian of the Apostolic College of San Fernando, proposed what he called a “new method” of evangelization, which was the congregation of neophytes on the new mission communities as had been done in the case of the Texas missions.43 This policy of congregation had a long history in the first missions in Central Mexico in the sixteenth century, and, as already noted, had been implemented in the Sierra Gorda and the Jesuit missions in South America. Congregation on the Texas missions was a pragmatic response to unique local conditions in the region. Hostile indigenous groups such as the Comanches and Lipan Apaches raided the missions. The Franciscans directed the construction of mission complexes with defensive features such as bastions, and the neophytes lived within the complexes that were surrounded by walls for their own safety.44

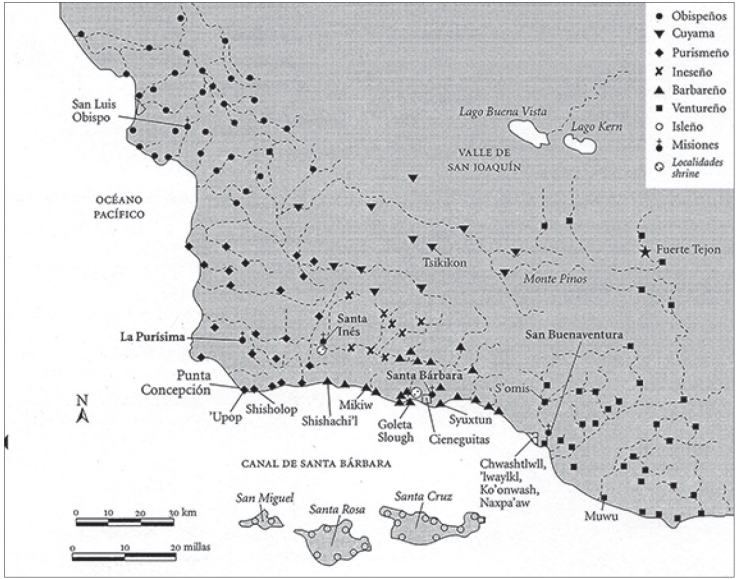

The Franciscans implemented the same policy of congregation on the California missions, and directed the construction of housing for the indigenous populations similar to that on the Jesuit missions among the Guaraní. The process on the mission established among the communities collectively known as the Chumash was typical. The Franciscans established six missions between 1772 and 1804 among the communities collectively known today as the Chumash, or that congregated people from Chumash communities. The first was San Luis Obispo (1772) and was followed by San Buenaventura (1782), Santa Bárbara (1786), La Purísima Concepción (1787), and Santa Inés (1804). The missionaries stationed on San Fernando (1797) also congregated numbers of Chumash.45

Patterns of the Chumash congregation in missions and their reasons for leaving their traditional lifestyle were very complex. The Franciscans established missions in places that satisfied certain requirements, including the availability of sufficient arable land, water for agriculture, and building materials. One of the most complex and controversial questions surrounding the California missions is why the natives abandoned their traditional way of life for a new life, culture, religion, and social order on the missions. In a study of the decline and collapse of tribal life in the San Francisco Bay region, anthropologist Randal Milliken suggested several reasons for the natives deciding to settle on the missions. At first, some Indians were attracted by the desire to be a part of something new, and maybe to obtain the novel manufactured goods the Spanish had. However, as the number of newly introduced livestock proliferated and destroyed traditional sources of food and disease spread among the native population, the missions became the only option as the old way of life disintegrated. The natives lost faith in a traditional way of life that had not prepared them to cope with the changes they experienced in missions. In addition, the social and political system, trade networks, and round of religious celebrations collapsed, the livestock the missionaries brought destroyed food supplies and finally, disease and migration reduced the size of the villages, leaving them vulnerable to attacks from other native groups from the interior.46

A recent study analyzes and compares the ecological impact of the introduction of sheep in Central Mexico during the sixteenth century, and in Australia in the nineteenth century.47 We can draw parallels with the experience of the effects of the introduction of European livestock on the Chumash. In Australia, sheep and cattle destroyed plants used as food by the aborigines. Moreover, English settlers prevented the controlled fire that the aborigines used to promote the growth of food plants, which led to the spread of weeds and a decreasing supply of wild food. The Spanish also restricted the controlled burns that the Chumash used to promote the growth of certain plants that produced edible seeds. Livestock grazing destroyed the surface layer of the plant cover that protected the earth and in semiarid areas, the destruction of the protective plant cover left dried and eroded soils.

The Franciscans introduced cattle, sheep, horses and other animals. Thousands of cattle and sheep roamed the Chumash territory, and the number of animals grew rapidly after 1800. In that year four missions reported a total of 16 572 cattle and 20 215 sheep, and a decade later, in 1810 the number totaled 41 425 cattle and 37 786 sheep. The common practice was to place livestock in a location near large native population centers, which meant that the growing number of animals destroyed plants that were traditional food sources for native people. The arrival of the Spanish and their livestock destroyed the economic base of their traditional lifestyle of the Chumash, and the missions offered the only alternative to a lifestyle that was rapidly disintegrating.

As their world collapsed around them, the natives found that they had no choice but to move to the missions. Another recent study employed risk minimization theory to explain why the Chumash moved to the missions and did so relatively quickly.48 Nearly 85 percent of those who were baptized relocated to the missions between 1786 and 1804, and just over 1 200 in the year 1803 alone. Based on an analysis of climate variations and changes in sea surface temperatures caused by the effects of el Niño, this interpretation argues that the Chumash voluntarily decided to move to the missions to minimize the risk of the variable and unpredictable traditional food supply made unreliable because of a changing climate, and particularly by the interruption of the Santa Bárbara Channel fisheries, which was the main source of food for the people of the Channel Islands and the coast. The collapse of traditional trade and political alliances together with the impact of epidemics and subsistence insecurity made the missions an attractive alternative to a traditional lifestyle that was in crisis and rapid decline.

The process of congregation of the natives on the missions was episodic. There were periods of intense recruitment, followed by years when the Franciscans recruited only a few. In the years 1802-1804, a large number of non-Christians settled on the missions (almost a quarter of the Chumash recruited). The arrival of hundreds of new residents caused a rapid increase in population. Between 1802 and 1804, the population of San Luis Obispo, Santa Bárbara and La Purísima increased by 38, 63 and 48 percent respectively. The population of Santa Bárbara totaled 1 093 at the end of 1802 and increased to 1 783 two years later. The population of San Buenaventura grew 38 percent between 1802 and 1808.49 In 1804, at the end of the push in Chumash congregation, the population of the four oldest missions -San Luis Obispo, San Buenaventura, Santa Bárbara and La Purísima- was 5 371. Thirty years later, in 1834 the numbers had fallen to 1 853. The populations of the Chumash missions were not viable, meaning that they did not grow through natural reproduction. The majority of baptisms recorded were of non-Christians resettled on the missions (see Table 2).

Table 2 Baptisms recorded on four missions established among the Chumash

| Mission | Mainland villages | Island villages | Births |

|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Bárbara | 2 633 | 368 | 1 426 |

| La Purísima | 1 862 | 213 | 1 192 |

| San Fernando | 419 | 0 | N/A |

| Santa Inés | 449 | 235 | 751 |

Source: John Johnson, “Chumash Social Organization: An Ethnohistorical Perspective”, unpublished PhD dissertation, University of California Santa Bárbara, 1988.

An analysis of the process of congregation at San Luis Obispo provides additional insights to an understanding of the resettlement of non-Christians on the missions. Between 1790 and 1795, the Franciscans relocated 482 natives to the mission, and 109 alone in 1791. It is important to note that in the year 1791 alone the Franciscans resettled 109. In 1789, the Franciscans baptized only five non-Christians, but a decade later, in 1803 at the height of the Chumash resettlement, 239 settled on San Luis Obispo.50 Santa Inés offers a second example of patterns of congregation. During the phase of active congregation between 1804 and 1819, the Franciscans baptized 686 converts. The maximum recorded population was 768 in 1816. After 1820 the number of Chumash settled on the mission declined. There were nine baptisms of converts between 1820 and 1833, and then a spike of 32 in 1834 and 1835. The population dropped to 344 in 1834 on the eve of secularization as death rates were higher than birth rates.51

The rate of congregation varied from mission to mission. At San Luis Obispo it was a longer and slower process, but the Franciscans also recruited from native communities further north which later came under the jurisdiction of Mission San Miguel, established in 1797. The natives from those communities transferred to the newly established mission. Between 1773 and 1794, the missionaries baptized almost 60 percent of all the non-Christians in the entire region, and the other 30 percent were baptized during the next decade. However, during the 1830s there was one last wave of congregation on San Luis Obispo. The Franciscans baptized 178 Yokuts from the Central Valley. Mission Santa Inés, on the other hand, evidenced a pattern of a more rapid congregation on the mission. A total of 93 percent of the baptisms of non-Christians occurred within the first fifteen years of the establishment of the mission.52

The mission urban plan

In the eighteenth century, reform-minded royal officials expected that the urban plan of frontier mission communities would conform to the grid plan and that the indigenous residents of the missions would live in European-style housing in a “civilized” fashion. This reform imperative was most fully developed on the California missions, and the housing arrangement for the neophyte population also was an element of social control. As a response to the expectation of royal officials for greater accountability from the missionaries, the Franciscans reported on building projects on the missions in the reports they prepared annually. The information from the reports allows for a reconstruction of the development of the mission complexes.

The Franciscans directed the construction of different types of buildings on the mission and incorporated a central plaza into the urban plan. The central mission complex consisted of the monumental church, and the cloister that contained apartments for the missionaries, quarters for visitors to the mission, granaries, storerooms and workshops. In terms of the chronology of the development of the complexes the Franciscans gave a higher priority to the construction of the church and cloister.53 The urban plan also included two forms of housing for the neophyte populations. The first was a dormitory for single women and girls entering puberty and in some cases dormitories for men and adolescent boys. The inclusion of dormitories for adolescent girls and unmarried women was an innovation introduced in the mission urban plan in California and was an effort by the Franciscans to control native sexuality and to confine sexual relations to Christian marriages. It also had a basis in the sixteenth century doctrinal stress on the teaching of the original sin and the final judgment on Central Mexican missions. Eve had tempted Adam in the Garden of Eden, and the missionaries presented women as the temptress that would lead men to sin.54 The Dominicans who staffed the Baja California missions after 1773 also introduced the use of dormitories as a form of social control.

The control of native sexuality had a high priority for the Franciscans. In the preparation of the annual reports the Franciscans did not always identify the use of every building, but where they did the dormitories for adolescent girls and single women were among the first constructed. Moreover, the dormitories became a standard element in the California mission urban plan. Table 3 summarizes references to dormitories. The record for Santa Bárbara Mission is more complete. The Franciscans included a dormitory among the first structures erected in 1786-1787, and as the mission population expanded, they had a new dormitory built in 1789. The first reference at San Fernando was to the construction of a dormitory in 1801. The Franciscans did not report the construction of a dormitory at La Purísima Mission but noted one among the structures damaged in the 1812 earthquake. There is an 1814 reference to repairs made to the dormitory at San Luis Obispo Mission. Unhygienic conditions in the dormitories for adolescent girls and single women contributed to high rates of mortality on the missions and are discussed below in more detail.

Table 3 Reports of the construction of dormitories for women on the Missions among the Chumash

| San Luis Obispo | Santa Bárbara | La Purísima | San Fernando |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1814-repaired | 1786-1787-built | 1812-damaged | 1801-built |

| 1789-built |

Source: Robert H. Jackson and Edward Castillo, Indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization: The Impact of the Mission System on California Indians (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 150-151, 156-159, 164, 166.

The urban plan on the California Missions also included European-style housing for neophyte families that usually consisted of rows of barracks-like buildings with small apartments that housed a single family, and complied with the Crown mandate to build new communities based on the grid plan. In the initial stages of the development of the mission complexes the neophytes generally lived in their traditional form of housing in villages adjoining the missions. However, once the major elements of the main complex had been completed the Franciscans directed the construction of new housing units for the neophytes. Table 4 summarizes the record of the construction of neophyte housing on the six missions among the Chumash. The neophyte housing was similar to that on San Miguel Mission among the Guaraní, although the configuration differed on some missions. The first mention of the neophyte village at San Luis Obispo was in 1781 when two sections of a wall were built around the neophyte village that most likely consisted of the traditional form of housing. Between 1801 and 1816, the Franciscans there directed the construction of 67 small apartments for neophyte families. At San Buenaventura mission there is a record of the construction of 69 small apartments in the years 1804-1806, and another 40 in 1818-1821. At Santa Bárbara the Franciscans had 252 housing units built between 1798 and 1807. An 1854 plat map of the mission site shows the ruins of the neophyte housing in a configuration similar to that of San Miguel Mission among the Guaraní. The annual reports for La Purísima Mission did not record the construction of neophyte housing at the first mission site but following the 1812 earthquake they listed 100 apartments for neophytes among the buildings damaged. Following the relocation of the mission to a new site in 1813 the Franciscans had at least two long barracks-style structures built with small apartments for neophyte families. The infirmary was added as an extension to one of the buildings.55 In 1804 the Franciscans had 70 units built at San Fernando, and another 40 in 1818. Finally, the Franciscans had 80 units built at Santa Inés in 1812 in a configuration similar to that at Santa Bárbara.

Table 4 Reports of the construction of neophyte housing on the missions among the Chumash

| San Luis Obispo | San Buenaventura | Santa Bárbara |

|---|---|---|

| 1781-wall around village | 1804-06 69 housing units | 1798-07 252 hosing units |

| 1801-six housing units built | 1818-21 40 housing units | |

| 1802-28 housing units built | ||

| 1805-13 housing units built | ||

| 1808-four housing units built | ||

| 1810-six housing units built | ||

| 1811-four housing units built | ||

| 1813-four housing units built | ||

| 1816-two housing units built | ||

| La Purísima | San Fernando | Santa Inés |

| 1812-100 housing units damaged in an earthquake | 1804-70 housing units built | 1812-80 housing units built |

| 1817-fountain Indian village | 1818-40 housing units built | |

| 1823-housing units built |

Source: Robert H. Jackson and Edward Castillo, Indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization: The Impact of the Mission System on California Indians (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 150-151, 156-159, 164, 166.

Demographic patterns

Congregation and the imposition of the new social, cultural, and economic order had demographic consequences for the indigenous peoples brought to live on the missions, including the Chumash. The mission populations were inviable, in other words, they did not grow through natural reproduction. The mission populations only expanded during periods of active congregation, and once the number of potential recruits dropped the numbers declined. The populations of the four missions declined 65 percent after 1804 while the Franciscans continued to relocate non-Christians. Epidemic and endemic diseases top the list of causes of high mortality rates on the missions and, the California mission populations did not rebound or recover from high or catastrophic mortality. Death rates on the California missions were consistently higher than birth rates. Epidemics spread over most of colonial Mexico along trade routes, although California remained fairly isolated until the expansion of the “hide and tallow” trade in the early nineteenth century. In 1820, Mariano Payeras, OFM, the missionary stationed at La Purísima, noted that there had been only two serious epidemics in the missions in the years following his arrival in 1796. One was in 1801, and the second was a measles outbreak in 1806 that killed hundreds of natives living on the missions. Payeras noted that some 150 died at La Purísima during the outbreak.56 Measles broke out again in 1827-1828 and killed both adults and children and further reduced populations already in decline by 9.1 percent.

What caused the decline of the Chumash populations congregated on the missions and how did the mission populations evolve demographically? An analysis of the extant baptismal and burial registers shows chronically high death rates, and death rates higher than birth rates. The case study of Santa Inés Mission documents the pattern. Crude death rates fluctuated but were high with an average of 78 per thousand population. There were periods of extremely high mortality, but no severe mortality crises (defined as 3 × normal death rates). In other words, mortality patterns at Santa Inés do not indicate a population being attacked by a series of epidemics causing catastrophic mortality, but rather a population declining as a result of chronically high mortality (see Table 5).

Table 5 Baptisms, Burials, and Population on Santa Inés Mission, 1804-1844

| Year | Baptisms | Crude Rates 1 000/ Pop. | Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Converts | Births | Burials | Birth | Death | ||

| 1804 | 109 | 3 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 225 |

| 1805 | 123 | 23 | 43 | 102 | 191 | 519 |

| 1806 | 78 | 30 | 75 | 58 | 145 | 570 |

| 1807 | 18 | 22 | 36 | 39 | 63 | 587 |

| 1808 | 12 | 21 | 32 | 36 | 55 | 583 |

| 1809 | 19 | 22 | 25 | 38 | 43 | 603 |

| 1810 | 39 | 20 | 34 | 33 | 56 | 628 |

| 1811 | 21 | 24 | 56 | 38 | 89 | 611 |

| 1812 | 7 | 28 | 35 | 46 | 57 | 611 |

| 1813 | 12 | 24 | 40 | 39 | 66 | 607 |

| 1814 | 4 | 27 | 33 | 45 | 54 | 588 |

| 1815 | 79 | 30 | 59 | 51 | 100 | 636 |

| 1816 | 156 | 27 | 50 | 42 | 79 | 768 |

| 1817 | 1 | 36 | 86 | 47 | 112 | 720 |

| 1818 | 4 | 26 | 69 | 36 | 96 | 681 |

| 1819 | 4 | 22 | 61 | 32 | 90 | 647 |

| 1820 | 0 | 33 | 45 | 51 | 70 | 635 |

| 1821 | 0 | 30 | 61 | 47 | 96 | 604 |

| 1822 | 0 | 23 | 45 | 38 | 75 | 582 |

| 1823 | 0 | 29 | 47 | 50 | 81 | 564 |

| 1824 | 0 | 14 | 34 | 25 | 60 | 516 |

| 1825 | 0 | 13 | 28 | 25 | 54 | 500 |

| 1826 | 0 | 21 | 34 | 42 | 68 | 487 |

| 1827 | 2 | 12 | 24 | 25 | 49 | 477 |

| 1828 | 0 | 11 | 33 | 23 | 69 | 451 |

| 1829 | 2 | 15 | 22 | 33 | 49 | 428 |

| 1830 | 0 | 11 | 19 | 26 | 44 | 408 |

| 1831 | 0 | 10 | 30 | 25 | 74 | 388 |

| 1832 | 3 | 6 | 37 | 16 | 95 | 360 |

| 1833 | 2 | 7 | 24 | 19 | 67 | 345 |

| 1834 | 15 | 12 | 30 | 38 | 87 | 344 |

| 1835 | 17 | 8 | 26 | 23 | 76 | N/A |

| 1836 | 0 | 10 | 12 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 1837 | 5 | 12 | 28 | N/A | N/A | 335 |

| 1838 | 2 | 14 | 33 | 42 | 99 | N/A |

| 1839 | 0 | 10 | 26 | N/A | N/A | 315 |

| 1840 | 1 | 13 | 17 | 41 | 54 | N/A |

| 1842 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 250 |

| 1844 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 264 |

Source: Robert H. Jackson, “Patterns Demographic Change in the Alta California Missions: The Case of Santa Inés”, California History, v. 71, n. 3 (Fall 1992): 362-369, https://doi.org/10.2307/25158649.

During the years of heavy recruitment, the neophyte population of the missions was relatively balanced, with roughly equal numbers of males and females. However, after 1816 the number of women of child-bearing age entering the mission dropped. Table 6 summarizes the sex ratio of males: females on five missions among the Chumash and shows the decline in the number of women and girls in relation to the total population in the 1820s and 1830s. Birth rates are particularly sensitive to changes in the number of women in the population. Between 1805 and 1824, crude birth rates on Santa Inés Mission averaged 45 per thousand population, but then dropped to 30 per thousand population in the years 1825-1829, and 25 per thousand population between 1830 and 1834.

Table 6 Sex Ratio (Boys above age nine and Men: Girls and Women) on five missions among the Chumash, in selected years

| Mission | 1796 | 1798 | 1810 | 1832 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Luis Obispo | 1.15 | 1.06 | 0.74 | 0.42 |

| San Buenaventura | N/A | 0.95 | 1.13 | 0.65 |

| Santa Bárbara | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.73 |

| La Purísima | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.01 | 0.62 |

| Santa Inés | N/A | N/A | 1.16 | 0.81 |

Source: Robert H. Jackson, Indian Demographic Decline: The Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1687-1840 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994), 113.

Endemic disease, and particularly syphilis, was an important factor. Responses to a questionnaire sent in 1814 to the Franciscan missionaries in California, noted the effects of syphilis on the native populations. For example, the missionaries stationed on San Fernando reported the spread of venereal disease among the population with numerous health consequences.57 It is known that syphilis infection weakens the immunological system and leaves its victims more susceptible to other infections. Additionally, complications from syphilis include the inability to conceive, premature births, high mortality in young children born with congenital malady, and lower birth rates. Mercury pills were the most common treatment for syphilis at the time, even though mercury is a deadly poison. During the first decade of the nineteenth century, missionaries from California included mercury pills among the drugs they ordered shipped from Central Mexico.58

Infant and child mortality was exceptionally high and reduced the ability of the native populations living on the missions to survive and reproduce. Table 7 records the percentage of deaths before age four among cohorts of children born on San Buenaventura, Santa Bárbara, La Purísima, San Fernando, and Santa Inés missions. Between 60 and 70 percent of all children died before reaching age four. Living conditions on the missions, poor hygiene, and disease killed most of them. In particular, children born infected with congenital syphilis passed from their mothers through the placenta generally did not survive a long time. Low birth weight was also a chronic problem and reflected inappropriate prenatal care. Even the simple act of breastfeeding carried with it serious health risks. One problem was the accumulation of residual milk in the mouth of the child, which caused the growth of bacteria, inflammation of the throat, and death. Another health threat occurred when the babies began to walk. Young children generally put anything they find into the mouth, which could become lethal to native children living in unsanitary conditions on the missions. A toddler that puts something filthy into the mouth could easily develop a severe case of diarrhea and quickly die, in some cases within 24 hours. As birth rates declined in the 1820s and 1830s and infant and child mortality remained high the number of young children in relation to the total population dropped. The Spanish used the term párvulo as a census category for children up to about age nine. Table 8 shows the drop in the number of children in this category on five missions in the 1820s and 1830s.

Table 7 Percentage of children born on five missions dead by age five

| Cohort | San Buenaventura | Santa Bárbara | La Purísima | San Fernando | Santa Inés |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1785-1789 | 40.4 | 71.4 | 46.7 | N/A | N/A |

| 1790-1794 | 71.4 | 73.4 | 55.9 | N/A | N/A |

| 1795-1799 | 67.0 | 78.4 | 59.6 | 90.0 | N/A |

| 1800-1804 | 76.8 | 73.9 | 68.8 | 85.5 | 25.0 |

| 1805-1809 | 78.4 | 64.9 | 70.2 | 68.6 | 59.2 |

| 1810-1814 | 52.0 | 57.3 | 57.7 | 60.0 | 55.0 |

| 1815-1819 | 60.8 | 59.0 | 70.5 | 51.5 | 79.0 |

| 1820-1824 | 57.1 | 68.3 | 67.6 | 63.0 | 73.1 |

| 1825-1829 | 63.7 | 68.4 | 71.7 | 61.9 | 58.3 |

| 1830-1834 | 53.0 | 41.8 | 59.3 | 46.9 | 48.9 |

Source: Sally McLendon and John Johnson, Cultural Affiliation and Lineal Descent of Chumash Peoples in the Channel Islands and Santa Monica Mountains, 2 v. [Washington, D. C.]: United States National Parks Service, 1999.

Table 8 Párvulos (children under age nine) as a percentage of the total population of five missions among the Chumash, in selected years

| Mission | 1789 | 1796 | 1798 | 1810 | 1832 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Luis Obispo | 26 | 14 | 15 | 11 | 6 |

| San Buenaventura | 35 | 12 | 14 | 10 | |

| Santa Bárbara | 29 | 14 | 14 | 22 | 15 |

| La Purísima | N/A | 23 | 18 | 11 | 9 |

| Santa Inés | N/A | N/A | N/A | 19 | 11 |

Source: Robert H. Jackson, Indian Demographic Decline: The Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1687-1840 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994), 114.

The Bourbon reform imperative to accelerate the integration of the mission populations in ways such as getting neophytes into European-style housing and housing conditions on the missions was also a factor in high mortality. In the early stages of the development of the missions, neophytes lived in houses that they had traditionally used. However, as discussed above, the Franciscans directed the construction of two new forms of housing: dormitories for single women and girls as well as single men, and adobe housing units for families. Natives living on the missions generally lived in unsanitary conditions. Furthermore, in the record of the construction of the California missions, there is no reference of latrines having been built. The Franciscans gave less attention to hygiene, and the water supply on the missions tended to be dirty and unhealthy, contributing to the spread of germs and diseases.59

In 1797, California governor Diego de Borica wrote a report on conditions in the missions and the Spanish settlements and noted the causes of the decline of the native population, already evident at that time. One factor that Borica mentioned was overcrowding and the unhealthy conditions in the dormitories where girls and single women lived. The Franciscans were obsessed with the sexuality of the native population and segregated girls and single women from the rest of the population. Dormitories for women were a standard feature on the missions.60 Borica reported how he entered a dormitory at one of the missions, but was overwhelmed by the smell of human feces.61 Before the Spanish arrived, the natives could burn dwellings that became too dirty or were infested by vermin. The Franciscans ordered the construction of permanent houses for the natives when populations were already large, and the housing constructed proved to be inadequate. At San Luis Obispo, for example, the population totaled 697 in 1801, when the first houses were built for the neophytes. At San Buenaventura it was 1 107 in 1804, 790 in Santa Bárbara in 1798, 985 in San Fernando in 1804, and 611 in Santa Inés in 1812, the years in which there is documentation of the construction of neophyte housing. The population of La Purísima fluctuated between 956 and 1 520 in the decade that the Franciscans began building 100 homes for families.

Resistance: the 1824 uprising

Some neophytes voted against life on the missions with their feet, fleeing to the interior that was still outside of Spanish-Franciscan control. The imposition of controls over traditional norms of sexuality, the use of corporal punishment, and the implementation of a new labor regime were factors for the resistance. However, the most serious threat was an uprising on three of the missions among the Chumash in February and March of 1824. Although it occurred decades after the main Bourbon reform initiatives and following Mexican independence in 1821, it was a consequence of the conditions created on the missions in the implementation of the Bourbon reforms. There had already been one instance of a short-lived revitalization movement in 1801 at Santa Bárbara Mission. A woman who had taken the hallucinogenic plant toloache had a vision of the earth goddess Chupu with the message that baptized neophytes would die, but that by washing off the effects of the baptism using water known as “tears of the sun” the people would be saved. The message of cultural resistance spread for three days until the Franciscans intervened and suppressed the movement.62 One reality on the missions during the period of active congregation was that the population was mixed with some who already had at least a thin veneer to Christianity and others who had not. It was easy for traditional religious practices such as the antap cult to persist in covert form. Several factors perhaps limited the effectiveness of the Franciscan evangelization campaign. One was the question of language, and the second the difficulty of translating Iberian Judeo-Christian religious concepts into a culture with a different world view and set of religious beliefs. In practical terms: how could the missionaries translate their concepts such as God, the Trinity, or the Resurrection into a language that did not already have words for these concepts?

The uprising began on February 24, 1824, after the corporal of the escolta had a neophyte from Santa Bárbara flogged at Santa Inés. The neophytes besieged the Franciscan missionaries and members of the escolta until re-enforcements arrived the next day from Santa Bárbara Presidio. The rebels then fled to La Purísima Mission that they then occupied for a month until a military force of 109 soldiers arrived on March 16 and defeated the rebels. When news of the revolt reached Santa Bárbara Mission an alcalde named Andrés led a group of some 400 neophytes into the interior where they organized along the lines of the missions but also incorporated elements of their own traditional religious beliefs and social norms of sexuality. In June of 1824, a military force went into the interior and brought some of the neophytes back to the mission. However, a number moved deeper into the interior where they continued to live for a decade until decimated by an epidemic.63

In his study of the uprising, James Sandos argued that the underlying cause was the use by the Franciscans of confessional aids to probe Chumash sexuality and social relationships in an effort to impose the new social-cultural norms.64 Sandos also reported evidence from Chumash informants of the covert practice of traditional religious beliefs. One informant stated that:

[…neophytes from Santa Bárbara Mission] secretly build little temples of sticks and brush, on which they hung bits of rag, cloth and other paraphernalia [and] depositing on the inside tobacco and other articles used by them as presents to the unseen spirits. This was an occasion of great wrath to the padres who never failed to chastise the idolators when detected.65

Did the probing through the confessional aids provoke the uprising? The hearing of confessions was already an established practice on the missions, and, as Sandos noted, the earliest known confessional aid was already in use several decades before the uprising. Moreover, the uprising occurred at the two missions where the Franciscans recorded the largest number of confessions in the years before 1824. At La Purísima, for example, the Franciscans reported 840 confessions in 1817 and 541 at Santa Inés in the following year. This was 88 and 70 percent of the population respectively.66

An alternative explanation is based on general conditions on the missions, and changes in the missionary personnel. In April of 1823, Mariano Payeras, OFM, died at La Purísima after being there for 19 years. During his long tenure, the Chumash neophytes most likely had become accustomed to his particular style of administration. Antonio Rodríguez, OFM, replaced Payeras, but remained only until September or October of 1824. It is likely that he introduced a different style of administration that the neophytes did not like. Marcos Antonio de Vitoria, OFM, replaced Rodríguez, and remained at La Purísima for more than a decade, and apparently had greater acceptance than had Rodríguez.67 Significantly, a comet appeared in the sky in December of 1823 and continued for several months until at least March. It most likely was seen as a portent of change.68 One such change had already occurred at La Purísima following Payeras’s death in April of the same year.

In a letter written in 1818 to another missionary who had already returned to the Apostolic College of San Fernando, Payeras provided other clues to help understand the causes of the 1824 uprising. Payeras wrote that conditions had changed dramatically and that there was considerable potential for violence on the part of the neophytes living on the missions. By the 1820s Chumash society on the missions was under considerable tension given that the missionary program that attempted to make radical changed in their way of life was advanced, even if the Chumash covertly retained cultural and religious elements. The political instability in Central Mexico after the onset of the Independence war and Mexican independence in 1821 resulted in greater labor demands as the presidios became more dependent on the missions for supply and financial support. Moreover, the mission populations were experiencing chronically high mortality rates, and the Franciscans were powerless to reverse the trend of decline. In their world view, the Chumash believed that the Franciscans were powerful shamans and intermediaries to the spirit world. However, their spiritual powers were no longer effective and sought new magic such as that of their traditional spiritual leaders who had been able to regulate their way of life for centuries.69 The appearance of the comet in the sky at the end of 1823 was the sign that it was time to make a change and expel the Spanish intruders. The brutal flogging of the neophyte from Santa Bárbara Mission who had gone to Santa Inés to visit a relative was the trigger that initiated the uprising.

The act of resistance by the Santa Bárbara Mission alcalde Andrés suggests another causal factor for the uprising. Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, the Chumash from different communities traded and interacted politically and socially with each other, and there was an established norm to regulate these interactions. That norm largely broke down following the imposition of the alien Spanish system. In other words, prior to the imposition of the mission regime, the Santa Bárbara neophyte would not have been punished for having gone to visit a relative in a neighboring community, but this occurred. Andrés led hundreds of Chumash into the interior to return to the old ways, but also with the material benefits of what the Spanish had introduced. While some of the fugitive neophytes returned to the missions, others moved deeper into the interior and created a new community independent of the controls of the missionaries and the military. This ultimately was the goal of the Chumash neophytes when they rose up in rebellion against the Spanish mission-military system.

Conclusions

Bourbon reformers expected results and greater accountability from the missionaries that staffed frontier missions. Royal officials tinkered with the Hapsburg system in the first six decades of the eighteenth century, and the reform of the Sierra Gorda missions was an example of this earlierreform impulse. However, the pace of reform accelerated obeying the implementation of military reorganization in the 1760s succeeding the defeat at the hands of the British during the Seven Years War. Administrative reform sought to save money and generate additional revenue to pay the costs of the creation of a standing army in Mexico and other Spanish territories in the Americas. Under the new model, royal officials expected the missions to cover their costs as much as possible. There was also a belief that missions that had operated for long periods of time such as those in the Sierra Gorda and Baja California were inefficient and a waste of royal resources, and the process of congregation and evangelization had to be accelerated and completed as quickly as possible. There was no master plan for the reform of missions on all of the frontiers of Spanish America. Rather, royal officials implemented local changes that were consistent with the reform impulse following the Bourbon ascension to the Spanish Crown, and particularly in the 1760s to the 1780s. The reorganization of the Sierra Gorda missions occurred two decades before the major push for reform in the 1760s, but still reflected the changing official view of the missions as they had operated under the older Hapsburg system. The reorganization of the Baja California missions in 1768 and 1769 and the implementation of civil administration on the former Jesuit missions among the Guaraní fully reflected the implementation of the new expectations.

Junípero Serra and the Franciscan missionaries from the Apostolic College of San Fernando administered the California missions along the lines of the system they had instituted two decades earlier on the Sierra Gorda missions and collaborated with the reform initiatives first of José de Escandón in the Sierra Gorda and later of José de Gálvez in the Californias. They imposed strong measures of social control as they had in the Sierra Gorda mission to ensure the rapid integration of the native peoples into the new colonial order. It included the use of corporal punishment and the imposition of a new economy and disciplined labor system. As had been the case in the Sierra Gorda, the Franciscans enjoyed military support in the relocation of native peoples to the missions, but a new twist was the assignment of soldiers to each mission to protect the missionaries and to enforce the new social norms and discipline. The availability of military support was a significant change under the reform initiative.

The implementation of the reform of the missions, and the imposition of social controls had demographic consequences. The populations congregated on the California missions proved to be inviable, that is they did not grow through natural reproduction. Rather, the mission populations expanded during periods of the resettlement of non-Christians on the missions, but then declined when the number of new recruits dropped. Significantly, there was a pattern of chronically high mortality among women and girls, and young children. The populations of the Jesuit missions among the Guaraní suffered catastrophic mortality in periodic epidemics but also rebounded or recovered following the epidemics. The mission populations did not evidence a gender imbalance as was the case on the California missions, and the formation of new families resulted in increased birth rates and population growth. Because of geographic isolation, few epidemics spread to the California missions, and the first outbreaks only occurred after 1800. The demographic inviability of the populations was a direct consequence of living conditions on the missions and the measures of social control the Franciscans imposed such as locking girls and single women up at night in unsanitary dormitories.

The secularization of the missions starting in 1834 did not result in the creation of stable pueblos de indios, as envisioned in colonial policy. Rather, local politicians took advantage of the colonization policy of the newly independent Mexican government to despoil the missions for their own benefit. Local officials granted land to their family, friends, and supporters, and stocked the ranches with mission livestock. The indigenous residents of the missions did not benefit, and the value of the mission estates dropped significantly. Instead of forming stable communities, the secularization of the missions resulted in the economic, social, and political marginalization of the indigenous populations.

Plate 6 A c. 1880 photograph of the ruins of the church and cloister of the first site of La Purísima Mission destroyed and abandoned following an 1812 earthquake

Source: Robert H. Jackson, “‘Han ignorado la amorosa voz del Padre’. Reconsiderando los orígenes del levantamiento de los chumash en 1824 en la California mexicana”, Desacatos, n. 10 (otoño-invierno 2002): 77-93.

Map 1 The Chumash villages and Missions

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)