Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Estudios de historia novohispana

versión On-line ISSN 2448-6922versión impresa ISSN 0185-2523

Estud. hist. novohisp no.47 Ciudad de México jul./dic. 2012

Artículos

The Chichimeca Frontier and the Evangelization of the Sierra Gorda, 1550-1770

La frontera chichimeca y la evangelización de la Sierra Gorda

Robert H. Jackson

Doctor en historia, con especialidad en la historia de América Latina, por la Universidad de California, Berkeley. Ha escrito o editado 11 libros y más de 60 artículos en revistas profesionales. Dirige el programa de la Alliant School of Management, Mexico City campus.

Recibido / Received: 10 de febrero de 2012;

Aprobado / Approved: 8 de mayo de 2012.

Abstract

In 1744 the Franciscans of the Apostolic College of San Fernando (Mexico City) established five missions for Pames at the Sierra Gorda region, in what now is the state of Queretaro. However these were not the first missions in that region: Augustinian and Dominican missions were established there in the mid-sixteenth century. This paper documents the first missions of the Sierra Gorda, the development of the Franciscan missions of the mid-eighteen century and the results for the Pames, who were hunters and gatherers, seen in a comparative text.

Keywords: Pames, Franciscans, Augustinians, Dominicans, evangelization, Sierra Gorda, College of San Fernando, 16th and 18th centuries

Resumen

Los franciscanos del Colegio Apostólico de San Fernando (México) establecieron cinco misiones para los pames de la región de Sierra Gorda, en lo que hoy es el estado de Querétaro, y dirigieron la edificación de templos con fachadas barro. Sin embargo estas misiones no fueron las primeras en esa región: agustinos y dominicos también establecieron misiones ahí a mediados del siglo XVI. Este trabajo documenta las primeras misiones de la Sierra Gorda, el desarrollo de las misiones franciscanas de mediados del siglo XVIII y los resultados para los pames, que eran cazadores y recolectores nómadas, visto en un texto comparativo.

Palabras clave: pames, franciscanos, agustinos, dominicos, evangelización, Sierra Gorda, Colegio de San Fernando, siglos XVI al XVIII.

Before being assigned to the ex-Jesuit missions in Baja California which served as a base for the colonization of Alta California, Fray Junipero Serra, O.F.M., and his colleagues from the apostolic college of San Fernando (Mexico City) attempted to evangelize Pames and other non-sedentary native groups in the Sierra Gorda region of the modern state of Querétaro. Following an inspection of the Sierra Gorda region conducted in the 1740s, José de Escandón, who had been given the task of colonizing Nueva Santander on the northeastern frontier of New Spain, petitioned viceregal officials to have Franciscan missionaries assume responsibility for the evangelization of the native peoples in the Sierra Gorda. For Serra and the Fernandinos, being assigned to establish missions in the Sierra Gorda was the first opportunity to implement in a real situation missionary theory, and the experience gained in the Sierra Gorda missions later served in the Baja California and Alta California missions. However, the arrival of the Fernandinos in the Sierra Gorda marked only a new phase in the history of largely failed efforts to evangelize the natives in the Sierra Gorda, which was a part of the sixteenth century Chichimeca frontier, the cultural divide between sedentary and nomadic native peoples.

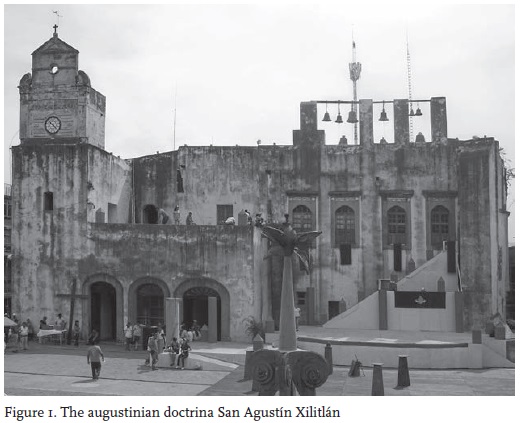

Augustinian missionaries first assumed responsibility for the evangelization of the Chichimeca frontier in what today are the states of Michoacán, Hidalgo, Querétaro, and San Luis Potosí including the Sierra Gorda in the 1550s and 1560s.1 The Augustinians stationed on the doctrina (convent-mission) Los Santos Reyes Meztitlán first attempted to evangelize the sedentary and non-sedentary natives living in the Sierra Alta of Hidalgo and neighboring areas, including the Sierra Gorda. The Augustinians established chapels in communities designated visitas that did not have resident missionaries and were visited periodically from Meztitlán. Three visita were located at Chichicaxtla, Chapulhuacán and San Agustín Xilitlán (see figure 1), the last two located in the tropical Huasteca region. Xilitlán was a community of sedentary natives subject to raids by nomadic Chichimeca groups moving into and competing for space in the Sierra Alta and Sierra Gorda.2 After 1550, the Augustinians elevated these three visitas to the status of independent doctrinas. In the 1560s the Augustinians established new missions at Xalpa (modern Jalpan) and Puxinguia in the 1560s in the Sierra Gorda region not far from Xilitlán, which served as the base of operations for the first effort to evangelize the Sierra Gorda region, which included several similar communities of saedentary nahuatl speakers such as Tilaco, which was a community in the district administered from Xilitlán.3 In 1569, the natives living in Xalpa and surrounding communities revolted. The rebels destroyed the Augustinian mission, and attacked Xilitlán and Chapulhuacán.4

Xalpa already appeared in records from the mid-sixteenth century. For example, it was one of the communities listed in the suma de visitas, a collection of summary reports that described different native communities written around 1550. According to the report, Xalpa was held in encomienda by one Francisco Barrón. The community counted 212 native tributaries, sedentary agriculturalists. The tribute consisted of three cargas or loads of clothing, nine jars of honey, and 200 birds. In addition to the tributaries, the report noted that there were also "many other chichimecas" (otros tantos chichimecas). Finally, the report noted that livestock ranches could be established in the Xalpa district, and wheat cultivated where practical.5 The uprising in 1569 may have resulted as much from the growing Spanish presence in the region and perhaps tribute demands, as from the presence of Augustinian missionaries.

The attempt to evangelize the Sierra Alta of Hidalgo and the neighboring Sierra Gorda region followed the system the Augustinians developed in the 1530s and 1540s in the areas of sedentary settlement in central México. In the early years of the missionary evangelization of central México the orders had limited numbers of missionaries, and could established convents with resident missionaries only at certain generally more important native communities. The convent at Meztitlán located in the Sierra Alta of Hidalgo provides an example of how the Augustinians managed the early stages of evangelization, and created new doctrinas when more personnel was available. The Augustinians established the doctrina at Meztitlán in 1539 (see figure 2).6 The Augustinians ministered scores of visitas throughout the Sierra Alta and neighboring Huasteca region, including Chichicaxtla, Calpulhuacán (see figure 3), and Xilitlán, which later became independent doctrinas. Other visitas of Meztitlán later elevated to the status of independent doctrinas were Tzitzicastlán, Zaqualtipán, and Ilamatlán.7

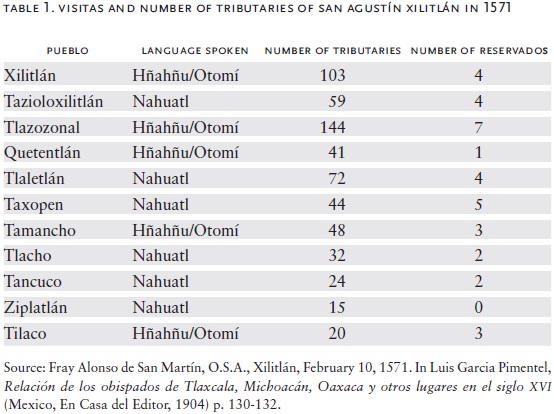

The Augustinian missions in the sixteenth century focused on the settlements of sedentary agriculturalists established at strategic locations beyond the Chichimeca frontier. A 1571 report on Xilitlán, for example, recorded the number of tributaries at the cabecera (head town) and visitas, (satellite communites) as well as the predominate language spoken by the residents of each community. The residents of the eleven communities that constituted the Xilitlán mission district spoke either Nahuatl or Hñahñu/Otomí. The report recorded Hñahñu/Otomí as the dominant language of both Xilitlán and Tilaco, which became a mission of Pames under the Franciscan regime established in 1744. Later documents show that the Augustinians did attempt to evangelize the nomadic hunter-gatherers they classified as Mecos, but the initial thrust of their mission was the evangelization of the colonies of sedentary natives.

The Augustinian missions along the Chichimeca frontier and particularly those in the Sierra Alta were subject to raids by Chichimeca bands, and several Augustinian missionaries died at the hands of the Chichimecas. In the 1580s, for example, Chichimecas raided San Agustín Xilitlán. The Augustinian chroniclers Juan de Grijalva, O.S.A., described Xilitlán and a Chichimeca attack in 1587:

(It is) very rough and with craggy land, the climate is hot and the Indians (are) very barbaric....In the year 87 the Chichimecas attempted to destroy the house (convent) and the town, (they) entered the lower cloister of the convent, robbed the sacristy and burned all that did not have arched ceilings (of stone) which was the greater part of the convent. The missionaries (religiosos) with some Indians had retired to the convent, defending the entrance to the upper cloister with such bravery that they escapted with their lives(.)8

In the same period Chichimeca bands raided other doctrinas, including Yuriríapundaro and Huango on the frontier in Michoacán.9

In directing the construction of the doctrinas and visita chapels the Augustinians incorporated defensive elements that were suitable for raids by nomadic warriors armed with lances and bows and arrows, and served as places of refuge in case of attack. One late sixteenth century source cited the construction of the Franciscan convent at Alfajayucan located in the Mezquital Valley on the Chichimeca frontier in Hidalgo, as having taken into account the threat of raids by the nomadic warriors.10 Augustinian constructions in the Sierra Alta also incorporated defense from Chichimeca raids, including defensive features built into visita chapels.11 An example is a chapel located in the Sierra Alta close to Meztitlán, which had a room built on top of the chapel that afforded greater protection in case of attack (see figure 4).

Fray Guillermo de Santa María, O.S.A., and the 16th century augustinian chichimeca missions

Fray Guillermo de Santa María was an Augustinian missionary active in the campaign to evangelize the Chichimecas living along and beyond the frontier in Michoacán. The history of these efforts to evangelize the Chichimecas provides context for the Augustinian missions in the Sierra Gorda. Santa María was one of the missionaries stationed on San Nicolás Tolentino Huango in 1550, which he used as a base of operations from which to visit Chichimeca bands along the river Lerma as far west as what today are Ayo el Chico and Las Arandas in Jalisco. In 1555 he congregated Purépecha and Guamares at Pénjamo and also administered a Chichimeca community at Ayo el Chico from Huango.12 It was a common strategy to settle sedentary natives on missions established beyond the frontier to serve as an example for the Chichimecas the missionaries attempted to congregate on the missions.

In the late 1560s, perhaps in 1566 or 1568, the Augustinians assumed responsibility for the former Franciscan mission among the Guamares Chichimecas at Villa de San Felipe, located in what today is northern Guanajuato on the border with San Luis Potosí, bordering the territory of Guachichiles Chichimecas. The Franciscans established a mission there in 1553, but abandoned the mission following the murder of Fray Bernardino de Cosín, O.F.M., by the Chichimecas. Guillermo de Santa María was one of three Augustinians stationed there in 1571, and wrote a report on the status of the mission and of a second community of Chichimecas established at a site known as Valle de San Francisco (Villa de Reyes, San Luis Potosí).13 The Augustinians settled Purépecha from Michoacán at San Felipe to assist in the attempt to evangelize the Guamares congregated there.

The three Augustinians stationed on the mission at the Villa de San Felipe were the prior named Gregorio de Santa María, O.S.A., Guillermo de Santa María, O.S.A., and Rodrigo Hernandez, O.S.A. Guillermo de Santa María reportedly assisted the prior in dealings with Chichimecas. The Augustinian spoke Purépecha and communicated with Chichimecas through native translators who also spoke Purépecha. He was responsible for the establishment of the mission at Valle de San Francisco among Guachichiles. The report alluded to the difficulties the Augustinians faced in trying to convert the "diverse and wild" Chichimeca bands, although the Augustinians believed they were achieving success in evangelizing the Guamares and Guachichiles.14 However, the Augustinians abandoned the missions in 1575 following a Chichimeca attack.15 In outlining measures to pacify the Chichimecas, Santa María recommended the re-establishment of the Augustinian missions at San Felipe and San Francisco.16

Guillermo de Santa María returned to Michoacán, where he was first assigned to Zirosto.17 He later moved to Huango again, where he died in 1585 at the hands of the Chichimecas. Before his death in 1585 he advised the Bishop of Michoacán on the question of whether or not the war with the Chichimecas was just or not. The Catholic Church council held in Mexico City in 1585 re-examined the issue of the conflict first addressed in 1569 at a meeting called by then Viceroy Martín Enríquez, at which time representatives of the three missionary orders endorsed the war.18 The 1585 council abandoned the Church's support for the war.19 The writings of Guillermo de Santa María contributed to the shift in attitude and provided important details regarding Chichimeca culture, Chichimeca attitudes toward the Spanish and their motives for the resistance, and the effort to evangelize them.

The argument in support of a just war against the Chichimecas cited the apostasy and rebellion of the Chichimecas against royal authority, and their attacks on and killings of clerics. Additionally, the Spanish considered other causes to have been Chichimeca attacks on Spanish settlements, thefts of Spanish livestock, and assaults on caravans and travelers on the roads.20

Santa María identified causes for Chichimeca hostilities that he saw as mitigating factors in considering continued support for the war against the Chichimecas, and proposed measures for pacifying the Chichimecas. In Santa María's opinion, the root cause for Chichimeca hostilities was enslavement of natives by Spaniards, and particularly Spanish soldiers who fought on the frontier without receiving a salary from the royal government and who enslaved natives to recoup their costs. The enslavement of Chichimecas began during the Mixtón War (1541-1542), a frontier conflict that Santa María witnessed. According to Santa María, this unjust enslavement was an important cause for hostilities.21 Santa María proposed congregating Chichimecas at several sites in their territory that included the important settlements at Epenxamu and Xichú which later was a mission site, and the re-establishment of the missions at San Felipe and San Francisco.22 The expectation was that once congregated and taught agriculture under the administration of the missionaries, the Chichimecas would embrace the new faith and their status in the new colonial order. As the history of the evangelization of the Sierra Gorda region shows, on the other hand, the expectations of the missionaries generally did not match reality.

Evangelization of the Sierra Gorda

Spaniards first established settlements beyond the Chichimeca frontier in the 1530s and 1540s, and accelerated colonization following the discovery of silver mines at Zacatecas and other sites beyond the frontier.23 In the second half of the sixteenth century Spanish settlement advanced northward fairly rapidly, but pockets of territory not subject to Spanish control remained behind the northern frontier of settlement, such as the Sierra Gorda region. Missionaries, including Augustinians, attempted to evangelize native groups living beyond the Chichimeca frontier after about 1550, and established missions among different Chichimeca groups such as the Pames. The missionaries often arrived following initial Spanish settlement. Pénjamo, located just beyond the river Lerma on the Chichimeca frontier in Michoacán, was an example. Spaniards established Pénjamo in 1542, and, as discussed in the previous section, the Augustinians established a mission there in the early 1550s. Hñahñu/Otomí and Purépecha settled on Pénjamo, and contributed to its development and defense. In the first years of the seventeenth century following the conclusion of the Chichimeca conflict, the native residents of Pénjamo petitioned to congregate the native population in the district there. Similarly, Spanish colonists penetrated Querétaro and the Sierra Gorda region before the arrival of the missionaries, including the region surrounding the Villa de Cadereyta and the semi-desert zone located between Cadereyta and the Sierra Gorda massif.24

In the 1560s the Augustinians established new missions at Xalpa (modern Jalpan, Querétaro) and Puxinguia in the Sierra Gorda region not far from the doctrina at Xilitlán. Within the Sierra Gorda were several other communities of sedentary natives including Xalpa, Concá, and Tilaco. The last named was a community in the district administered from Xilitlán inhabited by Hñahñu/Otomí speakers (see table 1).25 The missionaries stationed on the new doctrina at Xalpa administered visitas at Concá, La Barranca, and perhaps also Ahuacatlán.26

In 1568-1569, the natives living on Xalpa and surrounding communities revolted, destroyed the Augustinian mission, and attacked Xilitlán and Chapulhuacán.27 Luis de Carbajal described the uprising in the following terms:

(At the end of 1568) the Indians of the district and province of Xalpa, who before were subjects and tributaries, rebelled; and burned the principal town at Xalpa, which was (inhabited by) Mexicans (Náhuatl speakers), and burned the monastery and entered the towns of Jilitla and Chapulhuacán taking many captives ( despoblaron muchos sujetos) and toppled the churches, and as a solution, the Viceroy sent don Francisco de Puga, and in his place his Lieutenant, with twenty-four soldiers with a large salary and cost to Y(our) M(ajesty), and since I did not incur an expense for ten months, which was (a period) of continuous risk to my person, I subjected and rendered them (the rebellious natives) and put them at peace and subject to Y(our) M(ajesty), and reduced them to knowledge of God our Lord, from whose law they had apostate, and I rebuilt the town of Xalpa and built a fort of stone and lime which is among the best in New Spain, and inside of it a Church and Monastery(.) without cost to Y(our) M(ajesty), which building is worth more than twenty thousand pesos, which I (had constructed) myself, with which that land and the said towns of Jelitla, Chapuluacan, Acicastla and Suchitlan were secure for many years.28

Another account added that three Augustinians died when Chichimecas attacked and burned the church and convent, but gave the date of the attack as 1572. This may have been the same incident, or a second attack. The Augustinians killed were Fray Francisco de Peralta, O.S.A., Fray Ambrosio de Montesinos, O.S.A., and Fray Alonso de la Fuente, O.S.A. The account described the church and convent as being built of adobe walls with a packed earth roof.29

As occurred in other parts of central Mexico, jurisdictional disputes occurred between the Augustinians and the other missionary orders that competed for the mission territory in the Sierra Gorda. Intervention by royal officials resolved one jurisdictional dispute when Franciscans requested control of the missions at Xalpa and Concá. The Franciscans based their claim on a 1612 royal decree granting them jurisdiction over Concá and Rioverde (modern San Luis Potosí).30 Missionaries from all three orders also established and administered missions in the region during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. The Augustinians established new missions in the 1580s which included Xalpa and Concá. However, there was early competition from Franciscans. In 1601, for example, Fray Lucas de los Ángeles, O.F.M., stationed on the doctrina at Xichú (modern Guanajuato) visited the Sierra Gorda region and baptized natives at Concá and other communities including Escanela and Ahuacatlán, later sites of Dominican missions. In 1609, in response to complaints, Viceroy Luis de Velasco signed an order confirming the Sierra Gorda mission at Xalpa to the Augustinians.31

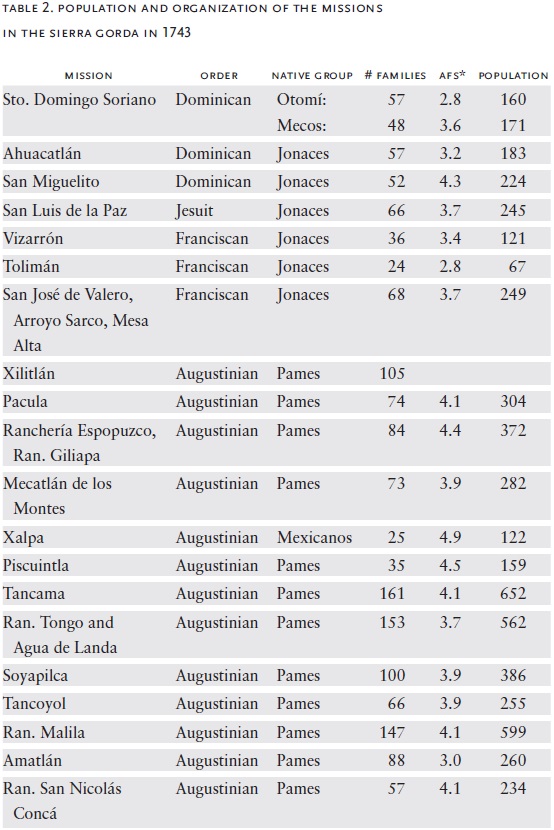

In 1743, when Escandón conducted his survey of the Sierra Gorda region, Lucas Cabeza de Vaca, O.S.A., administered the Augustinian mission at Xalpa. The mission district consisted of Xalpa, the settlements of San Juan Pisquintla San Juan Sagav, Atamcama, Santiago de Tongo, Santo Tomás de de Sollapilca, San Agustín Tancoyol, San Nicolás Malitlaand, San Antonio Amatlán, and San Nicolás Concá, which was a hacienda that belonged to one Gaspar Fernández del Pilar de Rama. There were 13 small settlements described as rancherías. The Augustinian churches were described as jacales, or wattle and daub construction. Escandón described and enumerated the missions in the region staffed by Dominicans, Franciscans, and the Augustinians (see table 2). The Augustinians administered several larger Pames settlements classified as rancherías, that they visited periodically from the missions at Xilitlán, Pacula, and Xalpa. Escandón criticized the Augustinians for their lack of progress in evangelizing the Pames, but the Augustinian system reflected the Pames settlement pattern with communities spread across the mountainous region, and the unwillingness of the natives to abandon their traditional way of life. In 1742 Cabeza de Vaca enumerated the population of the Xalpa jurisdiction. He found 134 families of people classified as gente de razón, 25 families of Nahuatl speakers known as Mexicanos, and 15 Pames families classified as Mecos at Xalpa itself that totaled 698 people, and 3 852 in the larger jurisdiction, although the Augustinian also believed that the population of the region was around 6 000.32

Cabeza de Vaca cited several reasons for the failure of the Augustinian mission. According to the missionary the natives resisted evangelization and resettlement on the mission communities and their consumption of locally produced alcohol as causes for the lack of progress. The Pames preferred to live in their own settlements, and only visited the missions periodically and often infrequently. Finally, Cabeza de Vaca petitioned for support from civil officials to take harsh measures to force the recalcitrant natives to accept sedentary life on the missions.33 Escandón judged the Augustinian mission to have been a failure, and petitioned the Viceroy to replace the Augustinians with Franciscans from the Apostolic College of San Fernando, in Mexico City.

The dynamic of religious conversion differed between sedentary and non-sedentary natives living on and beyond the Chichimeca frontier of the sixteenth century. Gerardo Lara Cisneros documents the persistence of the cult dedicated to hills, and the incorporation of Christian symbols such as the cross into religious rites. The persistence of traditional religious practices in communities populated by sedentary natives such as Xichú and San Luis de la Paz resulted in allegations of idolatry and apostasy.34 Rituals discovered on mountains, such as near Calimaya (Estado de México) on Palm Sunday in 1610, may have been related to the water-earth-fertility cult.35 In the sixteenth century missionaries, who believed that they had converted the native populations, instead discovered the covert persistence of tradition rites, such as the water-earth-fertility cult, that they categorized as idolatry.

One such instance of what the missionaries defined as idolatry occurred around 1540 at the Augustinian convent at Ocuila (modern Ocuilán, Estado de México), after the trial and execution of Don Carlos in 1539 at Tlatelolco. The Augustinian missionary Antonio de Aguilar, O.S.A., uncovered covert sacrifices to pre-Hispanic gods including bloodsacrifices in a cave close to the convent, most likely soon after the establishment of the mission. The idols and sacrifices in the cave were under the care of a native named Acatonial, and idols and other paraphernalia related to traditional religious practices were found in the houses of several natives including two named Suchicalcatl and Tezcacoacatl. Tezcacoacatl, who had been baptized by the Franciscans in Toluca and was a native of Michoacán, confessed, and also implicated a native carpenter named Collin who was not a Christian. The incomplete record of the Ocuila case does not indicate what punishment the missionaries applied to those implicated in idolatry.36

The Pames, on the other hand, preserved their traditional culture and religion by not cooperating with the missionaries. Cabeza de Vaca described and complained of a pattern of passive resistance on the part of the Pames, who simply refused to live on the missions or to attend religious instruction and mass. The Augustinians did not have the means to force the Pames to comply with the mission program, and the missions among the Pames continued to operate for several centuries from the sixteenth century to the end of the eighteenth century with mixed results.

In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries Franciscans and Dominicans established largely ephemeral and unsuccessful missions in the larger Sierra Gorda region. There essentially was little difference in the management of these missions, since they largely relied on having to entice the Pames and Jonaces to abandon their way of life, and did not have coercive power over the natives. In 1681 the viceregal government named one Gerónimo de Labra as protector of the Chichimecas, and gave him the task of congregating and evangelizing the natives in the Sierra Gorda. Working with Franciscans Labra directed the establishment of eight new misions in 1682 and 1683. In 1682 the Franciscans founded San Buenaventura Maconi, which was the headquarters of the group of new missions: San Nicolás Tolentino de Ranas, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe Deconi, and San Juan Bautista Tetla. In the following year the Franciscans added San Francisco Tolimán, La Nopalera, El Palmar, and San José de los Llanos (later re-established as San José Vizarrón in 1740). Also in 1682 two Franciscans from the Apostolic College of Santa Cruz de Querétaro went to Escanela, but later withdrew because the mission had already been assigned to the Dominicans.37

A decade later Fray Felipe Galindo, O.F.M., bishop of Guadalajara, received permission to establish missions in the Sierra Gorda. Galindo had eight missions founded. They were Nuestra Señora del Rosario, San José del Llano, San Buenaventura Maconi, Santa María Zimapán, Santo Domingo Soriano, San Miguel de las Palmillas, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe Ahuacatlán, which was initially a Dominican mission and was later returned to their jurisdiction, and Santa Rosa de las minas de Xichú. In 1703 the Jonaces rebelled against Spanish authority, and raided Rosario, San José, Maconi, and Zimapán missions, and forced the missionaries to abandon Rosario and San José. Royal officials established a presidio at the site of San José del Llano. In the aftermath of the rebellion the Franciscans ceded the missions at Soriano, Las Palmillas, and Ahuacatlán to the Dominicans.38 Troubles with the non-sedentary natives continued after the 1703 uprising. In 1713, for example, a militia force of 1 500 Spaniards and natives was on campaign in the Sierra Gorda, and demolished the Dominican mission Nuestra Señora de la Nopalera, claiming that the natives used the mission as a base of operations from which to raid settlements and haciendas.39

The continued active and passive resistance of the non-sedentary natives in the Sierra Gorda frustrated efforts at congregation and evangelization. The Jonaces, Pames, and Ximpeces Chichimecas lived scattered across the mountainous region in small bands. The Augustinian, Dominican, and Franciscan missionaries persuaded individual bands to settle on missions for short periods of time, but then the natives, and particularly the Jonaces, abandoned the missions and returned to their traditional way of life. In 1716 Franciscans from the Apostolic College at Pachuca entered the Sierra Gorda, and attempted to congregate and evangelize the Jonaces under the direction of Pedro de la Fuente, O.F.M., who founded the mission Santa Teresa de Jesús. A census prepared in 1718 highlighted the problem the missionaries faced. The census enumerated six Jonaces bands (cuadrillas) that ranged in size from 34 to 69 people, and altogether totaled 361 people. The bands lived dispersed in three or four different rancherías. De la Fuente convinced the Jonaces to settle on the mission, but the natives abandoned the mission after the Franciscan died in 1726. Those natives who did settle on the mission did so because of the influence of one particular missionary, but abandoned the mission following his death which was symptomatic of the limitations the missionaries faced in trying to convince the non-sedentary natives to change their way of life.40

A second example comes from a report on the Dominican missions San José and La Napolera from 1688. The population of the missions was divided among seven bands (cuadrillas). The enumeration of the bands provided complete information on only the first, that consisted of 21 families. The bands headed by Cristóbal, Felipe Sánchez, and Baltazar had fled to the mountains following a smallpox outbreak, which was a common response to epidemic outbreaks. The band headed by Tomás reportedly was absent in the Real de Escanela working for the Spanish there, and labor demands on the natives ostensibly congregated on the missions was seen as a major impediment to the work of the missionaries. Altogether, the seven bands totaled 79 families and 195 people, or an average of 2.5 people per family.41 Most of the natives were absent from the missions.

As a part of his plan for the colonization of Nueva Santander, José de Escandón reorganized the Sierra Gorda mission program (see figure 5). Escandón replaced the Augustinians with Franciscans from the Apostolic College of San Fernando. Fray José Ortes de Velasco visited the Sierra Gorda in 1739 and in the following year convinced 73 Jonaces to settle on the reestablished mission at San José de Vizarrón. Escandón gave the Fernandinos jurisdiction over the Augustinian mission at Xalpa and the visitas at Tancoyol and Concá, and ordered the establishment of new missions at Landa and Tilaco. The Franciscans congregated thousands of Pames on the new and reorganized missions. A census prepared in 1744 enumerated 3 767 Pames congregated on the five missions, with the largest number settled on Xalpa (see table 3).42

The Franciscans from San Fernando administered the mission at Vizarrón differently than did the Franciscans from Pachuca who staffed the Jonaces mission at Tolimán. The missionaries expected the Jonaces settled on Vizarrón to radically change their way of life in a short period of time, and in particular to become a disciplined labor force to work in communal agricultural production and livestock raising. The Jonaces did not respond well to this approach at directed social-cultural change, and the majority had abandoned the missions by 1748. In response, royal officials used force to recapture the fugitives, and distributed the natives among obrajes (textile mills) as forced laborers.43 In contrast, the Jonaces at Tolimán continued to collect wild foods, and were not subject to the same effort to change their way of life and convert the natives into a disciplined labor force.44 The Franciscans from San Fernando experienced a similar problem with the nomadic hunter-gatherer group known as the Guaycuras, in southern Baja California. The Fernandinos tried to convert the Guaycuras into a disciplined labor force after they replaced the Jesuits in Baja California in 1768, but the Guaycuras also resisted the forced and rapid change in life-style. The Franciscans ended up having to hire non-natives to work the mission lands the Guaycuras refused to work.45

The Pames congregated on the five missions established by the Franciscans responded differently to the economic system the missionaries introduced. The Franciscans distributed rations among the Pames to enhance economic dependence, and also to motivate the natives to work on communal agriculture, livestock raising, and building projects. As the communal mission economies produced more, the Franciscans were able to provide the Pames with daily rations, which in turn helped keep the natives on the missions.46 The 1758 report on Tilaco, for example, noted that: "In order to have them quiet and to keep them from wandering on the pretext of having to look for food, they are given daily sufficient corn and frijol from the communal {stores}, and on some days meat."47 The report from the same year for Xalpan noted the importance of communal agricultural production, and the daily distribution of a "ration very adequate for all, old and young, and on the most solemn days they kill some cattle and they give meat to all."48 The approach of using rations and the enhancement of economic dependence did not always work. The same group of Franciscans attempted the same approach on the Guaycuras in Baja California, with the outcome already noted above. This was also the same economic system the Franciscans from San Fernando implemented on the Alta California missions established after 1769, which was responsible for the production of large surpluses on those missions, although also with native discontent and resistance.49

The dilemma of evangelization: Demographic patterns and resistance on the Sierra Gorda missions in a comparative context

The Franciscans and royal officials envisioned a sea-change in the lifestyle of the Pames congregated on the missions established in 1744. They were to live congregated in larger communities, and practice a sedentary lifestyle. However, as occurred on other frontier missions established among nomadic hunter-gatherers, the Pames populations of the Sierra Gorda missions proved to be demographically fragile and inviable. In other words, the Pames populations did not grow through natural reproduction, and expanded only when the Franciscans congregated non-Christians on the missions. Periodic epidemics decimated the mission populations, and flight was one common response to the outbreak of contagion.

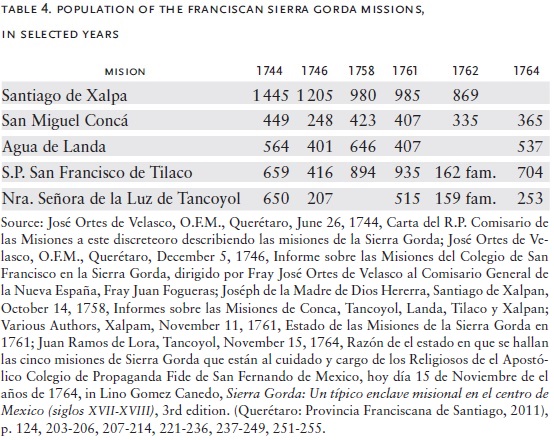

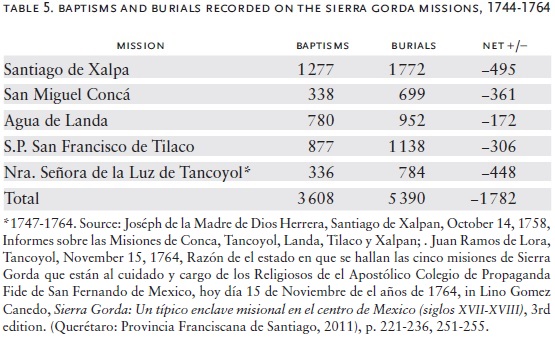

There were two severe epidemic outbreaks in the Sierra Gorda missions during the first two decades of the Franciscan administration. A report drafted about 1748 noted that in four years 1 422 Pames had died at four of the missions (there is no data for Tancoyol).50 Martin de Heredia, O.F.M., Juan de Uriarte, O.F.M., and Lucas Ladrón de Guevara, O.F.M., all died during the 1746-1747 outbreak.51 A smallpox epidemic in 1762 killed hundreds of Pames, as well as three Franciscan missionaries. Some 200 Pames died from smallpox in 1762 at Tilaco.52 The Franciscans maintained the population levels of the missions through the congregation of non-Christians although the populations of the missions slowly declined (see table 4). However, the fragility of the mission populations becomes evident on examining the net balance between baptisms and burials on the missions. Several reports summarize the total number of baptisms and burials recorded on the missions between 1744 and 1764 (see table 5). Over two decades there were 1 782 more burials than baptisms and during the same period of population of Xalpa dropped from 1 445 in 1744 to 869 in 1762. The recruitment of non-Christians buffered the decline on the other missions. Flight from the missions which reflected the unwillingness of many Pames to abandon their way of life also continued to be a problem.53

Baptismal registers exist for Tancoyol and Tilaco missions, and provide additional insights to demographic patterns on the missions. The register for Tancoyol records the first baptisms in 1747, but the Franciscans only started recording complete information on those baptized in 1754. In other words, they only began to record information in the individual baptismal entries as to whether it was of newborn child or a non-Christian resettled on the mission. The Franciscans stationed on Tilaco only began to record the complete information in 1753. Therefore, the analysis of baptismal patterns is limited to these years.

Between 1754 and 1770, the year that the Franciscans turned the mission over to parish priests following the secularization of the five Sierra Gorda establishments, they baptized 383 children born on the mission and several other rancherias administered from Tancoyol. That was an average of 23 births per year. The summary of the number of burials at Tancoyol indicates that the Franciscans on average buried 39 natives per year. The number of deaths was greater than the number of births. Despite the fact that Augustinians had administered Tancoyol as a visita of their mission at Xilitlán from as early as the 1550s, there were still unbaptized natives in the Tancoyol district. The Franciscans baptized 31 adults and 23 young children who were non-Christians (see table 6). Between 1752 and 1765 the Franciscans stationed on Tilaco recorded 435 births, or an average of 31 per year. The Franciscans recorded an average of 57 burials per year. From 1750 to 1765 the Franciscans baptized 56 adults who previously had not been baptized. Even with the influx of small numbers of non-Christians, the population of Tilaco constantly declined as the number of deaths was consistently greater than the number of births and baptisms of non-Christians (see table 7).

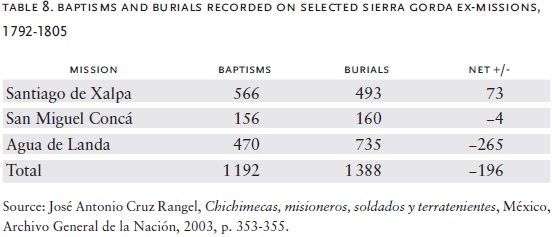

The Pames populations of the five Sierra Gorda missions analyzed here continued to be inviable following the secularization of the missions in 1770. A series of reports summarized the total number of baptisms and burials recorded on three of the former missions in the years 1792 to 1805 (see table 8). The Pames population of Santiago Xalpa showed a positive balance of 73 baptisms over burials, but this did not necessarily reflect more stable demographic patterns. It was equally possible that some natives died away from the former mission, and their deaths may not have entered the record. The Pames populations of Concá and Landa experienced a negative balance of 4 and 265 burials respectively, which was a pattern consistent with that documented for the period of administration by the Fernandinos.

The average family size (AFS) is a crude index of the size of families in a given population, and is calculated by dividing the total population by the reported number of families. The AFS can be useful in characterizing the dynamics of a population, when used in conjunction with other sources, such as detailed censuses that divide the population into enumerated family groups. Tables 2 and 3 calculate the AFS for the population of the missions in Escandón's count, and for the Sierra Gorda missions in 1744. The AFS indicates small family sizes with couples having one or two children. Non-sedentary peoples generally had fewer children than did sedentary natives. However, a low AFS could also reflect an incomplete congregation or resettlement of the population of a given band.

The problems the Augustinians and later the Franciscans encountered in their efforts to evangelize the non-sedentary natives living in the Sierra Gorda did not represent the failure of the missionaries or their methods, but rather the persistence of engrained cultural and social patterns and the unwillingness of the natives to abandon their traditional way of life. Missionaries on other frontiers experienced similar problems with nomadic hunters and gatherers who refused to abandon their way of life. Moreover, the populations of nomadic hunters and gatherers, such as the Coahuiltecos and Karankawas, proved to be equally demographically fragile as was the population of Pames congregated on the Sierra Gorda missions. This section examines several comparative case studies of the experiences of nomadic hunters and gatherers on missions. The first example examined here is a group of Franciscan missions on the north Mexican frontier in Coahuila and Texas in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The second example is of one of the Jesuit missions in the Chaco region in modern day Argentina, established among a group known as the Abipones. The Abipones adopted the use of the horse, and became formidable mounted warriors who gained status from their equestrian skills, and rejected agriculture which was too closely related to the collection of wild plants that was the gendered work of women, and not men.

The Spanish initially colonized Coahuila in the late sixteenth century. Mining and ranching were the main economic activities. In the 1670s natives subject to labour drafts solicited the establishment of missions by Franciscans, to serve as a buffer against the demands of Spanish entrepreneurs. Between 1699 and 1703 the Franciscans established three missions on the south bank of the Rio Grande river that they named San Juan Bautista, San Bernardino, and San Francisco Solano.-they had already established other missions further south.54 The natives in northern Coahuila were nomadic hunters and gatherers that lived in small bands and exploited different food resources within a clearly identified territory. They were similar to the Chichimecas living in the Sierra Gorda in terms of their social and political organization.

In 1718 the Franciscans relocated San Francisco Solano mission to the San Antonio area in central Texas. They retained San Juan Bautista and San Bernardino on the Rio Grande river. The populations of the two missions were unstable, and the numbers fluctuated as a consequence of the effects of disease and the abandonment of the missions by natives who elected not to remain. The Franciscans recorded the total number of baptisms and burials recorded at the two missions in reports prepared in 1777. Between 1703 and 1777, for example, the missionaries stationed on San Bernardino baptized 1 618 natives and buried 1,073. This left a net difference in population of 545. In the same year only 80 natives lived on the mission.55 Some 465 were unaccounted for, and most likely had left the mission. A fragment of the baptismal register for San Francisco Solano mission survives, and provides further insights to the social and demographic dynamic of the mission population. The Franciscans recorded a total of 53 different band names in the baptismal register, many of which also appear in other contemporary documents.56

The nomadic hunters and gatherers living in small bands proved to be demographically fragile and disappeared within several generations of the establishment of the missions. A mobile life-style imposed limitations on the number of children couples could have, since small babies and toddlers had to be carried by their parents. The calculation of the average family size suggests that the non-sedentary natives in the Sierra Gorda had small families, although this data needs to be interpreted carefully. Disease quickly decimated populations that did not have large numbers of children, and infant and child mortality rates were high. Moreover, those individuals, families, and groups that avoided or left the missions found their traditional economy eroded as growing numbers of Spanish livestock consumed food plants that traditionally were a part of their diet. Moreover, established social and trading networks collapsed. The independent bands rapidly disappeared as distinct populations, as did the non-sedentary natives in the Sierra Gorda.

The Franciscans established several missions along the Gulf Coast of Texas among a group collectively known as Karankawas, who lived in bands and practiced a well-established pattern of seasonal transhumance between permanent village sites in the interior and along the coast. The first two missions were Espíritu Santo that occupied several sites between 1722 and 1749 until relocated to its current location, Rosario, established in 1754, and Refugio, established in 1793 and relocated again in 1794 and 1795. The analysis of censuses and a baptismal register for Refugio for the years 1780-1828 show that the natives came and went from the mission on a seasonal basis, and in some cases were absent from the mission for several years. As was also the case in the Augustinian missions in the Sierra Gorda, there were cases of the baptism of children of previously baptized adults months or in two instances three and four years respectively following their birth away from the mission. The Karankawas interacted with the Franciscans on their own terms, and most likely saw the mission as an additional seasonal food resource.57

The next case study is of a mission established among nomadic populations of hunters and gatherers in the Chaco region of South America that operated for short periods of time.58 The Jesuits were unable to convince the different native groups to permanently settle on the missions, and change their way of life to become sedentary agriculturalists. The Chaco mission examined here is San Fernando de Abipones, chosen because a census prepared in 1762 recorded baptisms and burials for nearly a decade, and included detailed information on demographic trends that reveal the failure of the mission.59

The Jesuits established San Fernando de Abipones in 1750, on the western bank of the river Paraná, opposite Corrientes. Following the Jesuit expulsion the Franciscans staffed the mission until the beginning of the independence movement in the Río de la Plata region, at which point the Abipones resumed raiding Spanish settlements as they had done before the establishment of the mission. The missionaries abandoned the mission, thus ending the effort to establish missions among the nomadic Chaco groups.60

Demographic patterns on San Fernando de Abipones were distinct, and reflected the difficulty the Black Robes faced in trying the change the way that Abipone men behaved. The Jesuits primarily baptized children and very few adults. Those adults who accepted baptism did so only on the point of death. The Jesuits failed to convince most adults to accept baptism, which signified changing their way of life. The evidence from the 1762 census suggests that the Abipones permitted their children to be baptized, which may have been the one condition the Jesuits could demand in return for admission to the mission community. Few Abipones were buried at the mission. The adults rejected the new faith, which included receiving extreme unction and burial, and many adults most likely died away from the mission.61 An analysis of the age and gender structure of San Fernando de Abipones shows that women and children constituted the majority of the population, and Abipones' men chose not to reside on the mission. The evidence, in turn, shows that the Abipones used the mission as a place of refuge to leave their women and children when they went to hunt, or to wage war on rival native groups.

The secularization of the Sierra Gorda missions

The 1767 expulsion and removal of the Jesuits from Spanish American missions created considerable strain on the Franciscan Apostolic Colleges in Mexico, that had to find personnel to staff the missions left vacant by the removal of the Black Robes. The Franciscans from San Fernando were given responsibility for the former Jesuit missions in Baja California, and within a year planned the drive to establish missions in Alta California in response to an initiative launched by José de Gálvez. Mission secularizations, or the transfer of jurisdiction to secular priests under Episcopal authority, followed in the wake of efforts to staff the former Jesuit missions. The decision to secularize the Sierra Gorda missions was a direct consequence of the need to staff new mission assignments.62

The process of secularization presumed that the natives living on the missions were sufficiently acculturated to exist in colonial society without the intervention or mediation of the missionaries. Communal lands and livestock were to be distributed to the heads of household, which was done in the five Sierra Gorda missions. The Pames received house lots (solares) of different sizes. At Jalpan the lots measured 40 x 60 varas (1 vara=.838 meters); at Tancoyol 28 x 50 varas, at Concá 25 x 50 varas, at Landa 40 x 30 varas, and 26 x 33 varas at Tilaco. Livestock was also distributed, but agricultural implements remained communal property. In theory the goal of these redistribution of land and livestock was to guarantee the economic independence of the natives, but in practice Spanish settlers generally became the primary beneficiaries. Many Pames took advantage of mission secularization to leave and return to their old way of life.63

Breaking the mold: architecture and urban plan on the Sierra Gorda and California missions

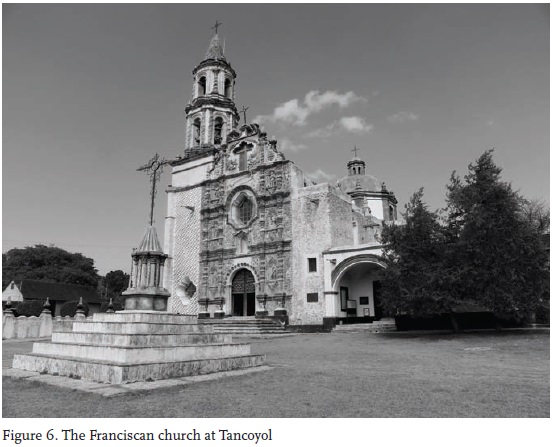

The elaborate baroque churches built under the direction of the Franciscans at all five Sierra Gorda mission sites have been restored, and UNESCO has added the group of five Franciscan missions to its list of World Cultural Patrimony sites (see figure 6). While unique in terms of the detailed baroque design elements incorporated into the facades, the Sierra Gorda missions also incorporated architectural elements characteristic of the earlier sixteenth century central Mexican missions that were not later employed in the California missions also staffed by the Franciscans from the Apostolic College of San Fernando. These elements included the atrium, the open space in front of the church and convent enclosed by walls used to gather the native population, open chapels, and capillas posas at the corners of the atrium used as stopping points for processions (see figure 7). The Sierra Gorda missions drew upon architectural elements developed by the Franciscan, Dominican, and Augustinian missionaries in the sixteenth century, but the two easternmost, Tilaco and Tancoyol, incorporated the complete set of elements with the capillas posas. These architectural elements may have already existed when the Fernandinos assumed responsibility for the older Augustinan missions. For example, the Augustinians had administered Tilaco as a visita of their doctrina at Xilitlán, but in response to Escandón's pressure had already assigned a missionary there in 1743. The Augustinian missionary stationed at Tilaco directed the first stages of construction of a church and convent. Escandón criticized the Augustinians for not having constructed churches at all of the sites they administered, including Tilaco, and used this as one justification for assigning the Franciscans to the missions. The Augustinians responded to his criticism by explaining that they had not constructed a permanent church and convent and had not left statues and other religious paraphernalia at Tilaco because they did not trust the "Mecos Barbaros" to not destroy them without the supervision of a resident missionary.64 Permanent structures built during the Augustinian administration also existed at other of the missions. A 1744 inventory of Xalpa, for example, described the convent built under the direction of the Augustinians as being built of stone and adobe, and with seven rooms.65

The Sierra Gorda mission churches were quite different, with baroque Christian themes and decorated in vibrant colors. However, the design elements on the church facades also incorporated themes found in sixteenth century central Mexican churches, such as plants and fruit. The architecture of the Sierra Gorda missions is interesting from another perspective when viewed in a comparative context. Serra and his colleagues incorporated sophisticated and elaborate design elements in the facades of the Sierra Gorda churches, and the construction of stone churches constituted a considerable investment of labor and communal mission resources. The evidence suggests that the Franciscans initiated a major construction campaign in the 1750s, as the mission economies reached a level of greater stability. The Franciscans directed the construction of the new church at Concá from March 1750 to September 1754, and measured 37 x 8 varas. The churches at Landa, Tancoyol, and Tilaco had been completed by the end of 1758. The report from that year also noted that construction had begun on the sacristy at Tancoyol, and that the Franciscans had blessed the new church at Tilaco on October 3, 1758. The church at Jalpan was nearing completion at the end of 1758.66

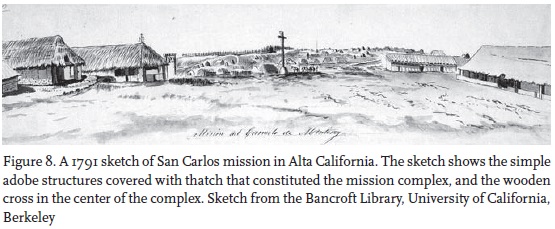

The later churches built in the California missions under the direction of the Franciscans from San Fernando generally were plainer, and did not incorporate similar design elements or themes as those incorporated in the Sierra Gorda churches or earlier sixteenth century structures. Moreover, the California mission building complexes did not incorporate other architectural elements found in the Sierra Gorda missions and the sixteenth century convent complexes, such as a walled atrium, decorated atrial cross oriented towards the entrance to the mission church, and particularly the capillas de posa. The architectural style and urban plan of the Franciscan California missions was much simpler than that of the Sierra Gorda missions.

The Spanish government required the Franciscans stationed on the California missions to prepare regular reports on the progress of the missions. Among other information, the annual reports contained summaries of building construction on the missions. The reports provide a detailed chronology of the sequence of construction projects as well as details on the different types of buildings erected. In addition to churches, the Franciscans directed the construction of the cloister that contained their own residence, storerooms and grannaries, workshops, and apartments for visitors. Other structures in the larger complex included housing for the native population, mills, and residences for the soldiers stationed on the missions to protect the missionaries. The Franciscans placed considerable importance on the mission economies, and had farms and ranches developed at different sites within the mission territory.67

Two contemporary illustrations of San Carlos (established 1770), one of the Alta California missions, give a sense of the progress in the development of the mission complexes, and the urban plan developed (see figures 8-9). The first from 1791 shows simple adobe structures roofed with thatch. An undecorated atrial cross stands in the center of the complex, and housing for the native populations still consisted of the traditional oval-shaped thatch structure. An 1827 etching shows the fully developed mission complex with a larger stone church, European-style housing for the native population, and the simple wooden atrial cross facing the church. The facade of the church was plain, and did not contain any of the baroque design elements on the Sierra Gorda churches. The mission complex also did not include the other elements found in the Sierra Gorda missions or the sixteenth century central Mexican doctrinas.

In the 1850s, the bishop of California petitioned for ownership of the land immediately surrounding each of the mission sites. Surveyors prepared plat maps for each of the mission sites as a part of the title process. These plat maps also document the elements of the fully developed mission complexes, although by 1854 when the surveyors prepared the maps some structures were in a ruined condition for lack of maintenance. The plat maps for Santa Barbara (established 1786) and San Miguel Arcángel (established 1797) provide a complete picture of the types of structures at the mission sites (see figures 10-11). The two maps show the church and cloister, as well as housing for the native populations. Moreover, the Santa Barbara plat map documents the irrigation system. These early maps also illustrate the absence an enclosed atrium and other architectural elements found in the Sierra Gorda missions.

Conclusions

In the second half of the sixteenth century the Franciscan, Dominican, and Augustinian missionaries encountered the non-sedentary peoples collectively known as the Chichimecas along the porous cultural divide between sedentary and nomadic native peoples. Efforts at the congregation and evangelization of non-sedentary natives proved to be difficult and frustrating for the missionaries, who outwardly had rapidly converted the sedentary natives of central Mexico. The frustrating experiences with non-sedentary peoples who generally resisted forced changes in their way of life would be repeated on numerous mission frontiers in northern Mexico and on other frontiers over the next centuries.

The Augustinians first attempted to evangelize the different native populations of the Sierra Gorda region in the mid-sixteenth century using the doctrinas at Meztitlán and Xilitlán as bases of operations. The non-sedentary natives generally resisted the evangelization efforts and the Augustinian missions in the region were only the first in a long series of initiatives begun by representatives of the three missionary orders that proved to be short-lived failures. The Chichimecas lived scattered across the region in small bands, and only settled on the missions for short periods of time before leaving or rebelling. The Augustinains staffed missions in the Sierra Gorda for more than a century, and in that time failed to convince most of the nomadic groups to accept mission life. The stability in their mission program in the Sierra Gorda rested on the communities of sedentary natives established in the region, such as Xalpa.

The experiences of Guillermo de Santa María, O.S.A., an Augustinian stationed on and beyond the sixteenth century Chichimeca frontier, exemplified the disconnect between the goals of the missionaries and the social-cultural realities of the nomadic hunter-gatherers living beyond the frontier. The natives did not readily embrace the vision the missionaries had for the new colonial social order, and one factor certainly was the different gender labor roles and the changes that a sedentary agricultural life entailed. Initial contacts between the Spanish and the groups collectively known as the Chichimecas were not violent, but abuses by the Spanish including the enslavement of natives provoked the conflict known as the Chichimeca War that lasted for half a century. Santa María himself was a victim of the war, and was one of a number of Augustinians killed in Chichimeca raids in the second half of the sixteenth century.

The last missionary initiative in the Sierra Gorda, that of the Franciscans from the Apostolic College of San Fernando, initiated under the directions of José de Escandón, lasted only several decades until 1770, when the government ordered the secularization of the missions following the expulsion of the Jesuits. The Fernandinos drew upon the previous experiences of earlier missionaries in the region, but also faced similar difficulties with non-sedentary natives who did not readily abandon their traditional way of life. Serra and his companions also gained experience they applied when the Fernandinos were ordered to replace the recently expelled Jesuits in Baja California, and when José de Gálvez organized the colonization of Alta California. In the Sierra Gorda missions the Fernandinos used the provision of food rations to promote dependence by the Pames, and as an enticement to remain on the missions. This economic-labor system functioned reasonably well on the Sierra Gorda missions, and was the basis for the economic system on the later California missions.

The effort to radically modify the way of life of nomadic hunters and gatherers met with mixed results, but also brought serious demographic consequences, as was seen in the case of the Sierra Gorda missions. The congregation of larger populations into compact communities facilitated the spread of contagion, and epidemics killed hundreds of Pames living on the missions. Over several decades the missionaries registered more burials than baptisms, and the mission populations were inviable, did not reproduce through natural reproduction. There is a larger common thread that links the history of the Sierra Gorda missions to missions on other frontiers established among nomadic hunters and gatherers. The demographic fragility of nomadic populations was one reality, but so was resistance to or a reluctance to abandon traditional ways of life and social norms that dictated status as related to certain gendered activities such as hunting and warfare. Missionaries along the frontiers of Spanish America experienced considerable difficulty with nomadic peoples they tried to settle on missions.

The architecture and urban design of the California missions was different from the Sierra Gorda missions. Structures such as the churches were simpler and lack the ornate design elements found on the Sierra Gorda missions. Moreover, elements such as an enclosed atrium and capillas posas were not included in the California mission complexes. The Franciscan missions in the Sierra Gorda did include these elements that the sixteenth century missionaries first incorporated into the convent complexes. Historic images of one of the California missions does show the equivalent of an atrial cross, but it was constructed of wood and not of stone as was common in the central Mexican doctrinas, and did not contain design elements such as the arma Christi that commonly appeared on central Mexican crosses. The Franciscans from the apostolic college of San Fernando who administered both the Sierra Gorda and California missions adopted a simpler and perhaps more functional design for the California missions.

1 Three colonial-era Augustinian chronicles document the missionary activities of the order in central México beginning in 1533 and the expansion of the number of missions on the Chichimeca frontier after 1550. See Juan de Grijal-va, O.S.A:, Crónica de la Orden de N.P.S. Agustín en las provincias de la Nueva España, Mexico, Editorial Porrúa, 1985, CL-343 p. [ Links ]; Diego Basalenque, O.S.A., Historia de la Provincia de San Nicolás Tolentino de Michoacán, del Orden de N.P.S. Augustin, 2 volumes México, D.F.: Tipografia Barbedillo y Cia., 1886, v. 1 CL-485 p., v. 2 CL-462 p. [ Links ], and Mathias de Escobar, O.S.A., Americana Thebaida vitas Potram: De los Religiosos Ermitanos de Nuestro Padre San Agustín de la Provincia de San Nicolás de Michoacán, Morelia, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, 2008, 695 p. [ Links ].

2 José Félix Zavala, "Los frailes agustinos, primeros en la Huasteca y en La Sierra Gorda" El Oficio de Historiar, Internet site http://eloficiodehistoriar.com.mx/2008/05/24/los-agustinos-primeros-frailes-en-la-huasteca-y-la-sierra-gorda/. [ Links ]

3 Grijalva, Crónica p. 192, 217; [ Links ] Arturo Vergara Hernández, El infierno en la pintura mural augustina del siglo XVI: Actopan y xoxoteco en el Estado de Hidalgo, Pachuca, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, 2008, 219 p., p., 91, 136. [ Links ]

4 María Elena Galaviz de Capdevielle, "Descripción y pacificación de la Sierra Gorda," Estudios de Historia Novohispano, México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, v. 4, enero de 1971, p 1-37; p. 10. [ Links ]

5 Francisco del Paso y Troncoso, Papeles de Nueva España. Segunda Serie Geografía y Estadística. Tomo I Suma de visitas de pueblos por orden alfabético, Manuscrito 2800 de la Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid, Anónimo de la mitad del siglo XVI, Madrid, Tip. Sucesores de Rivadeneyra, 1905. CL-332, p. 299-300. [ Links ]

6 Grijalva, Crónica ... , p. 204.

7 ibid., p. 204, 299.

8 The original quote reads: "(xilitla) es muy aspero y de tierras muy gragosas, el temple calido y los indios muy bárbaros...El año de 87 acometieron los Chichimecas a destruir la casa y el pueblo, entraron al claustro bajo del convento. Robaron la sacristia y quemaron todo aquello que no era de boveda, que era buena parte del convento. Los religiosos con algunos indios que habian retirado al convento, defendieron la entrada del claustro alto con tanto valor que escaparon con la vida." Grijalva, Crónica p. 192.

9 John McAndrew, "Fortress Convents?", Anales delinstitutio de investigaciones Estéticas, Mexico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, v. 23, 1955, p. 31-38, [ Links ] McAndrew based his description on the chronicle of Mathias de Escobar, O.S.A.. See Escobar, Americana Thebaida..., p. 431. Escobar also documented attacks on another convent located on the Chichmeca frontier close to Yuririapúndaro named San Nicolás Tolentino de Guango. The chronicle identified the raiders as the Saeta Chichimecas. See Escobar, Americana Thebaida... , p. 526.

10 The quote describing the construction of the convent at Alfajayucan comes from Philip W. Powell, La guerra chichimeca, 1550-1600. first Spanish edition, México, Fondo de Cultura Economica, 1977, 308 p.; p. 276, [ Links ] note 53. McAndrew also cites the same description. See McAndrew, "Fortress Covents", p. 33.

11 On this point see Antonio Lorenzo Monterrubio, "Las construcciones religiosas defensivas en la frontera sur oriental de la Sierra Gorda," Consejo Estatal para la Cultura y las Artes de Hidalgo, Internet site. http://cultura.hidalgo.gob.mx/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=673&Itemid=399&Itemid=399. [ Links ]

12 Guillermo de Santa María, Guerra de los chichimecas (México 1575- Zirosto 1580), edición crítica, estudio introductorio, paleografía y notas por Alberto Carrillo Cázares, Zamora, El Colegio de Michoacán, 2003, 270 p.; p. 84-85. [ Links ]

13 ibid., p. 86-87.

14 Relación de la Villa y Monesterio de S. Felipe, in Joaquin García Pimentel, Relación de los obispados de Tlaxcala, Michoacán, Oaxaca y Otros Lugares en el siglo XVI, Mexico, En Casa del Editor, 1904, CL-190 p.; p. 122-124. [ Links ]

15 Santa María, Guerra de los Chichimecas..., p. 89.

16 ibid., p. 201-202.

17 ibid., p. 89.

18 ibid., p. 84-85.

19 Arturo Vergara Hernández, Las pinturas del templo de Ixmiquilpan: ¿Evangelizacion, revindicacion indígena, o propaganda de guerra?, Pachuca, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, 2010, 198 p.; p. 145-153. [ Links ]

20 Santa María, Guerra de los Chichimecas... , p. 222-223.

21 ibid., p. 232.

22 ibid.

23 Gabriela Cisneros Guerrero, "Cambios en la frontera chichimeca en la región centro-norte de la Nueva España durante el siglo XVI," investigaciones Geográficas Boletín Mexico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geografía, v. 36, junio de 1998, p. 57-70. [ Links ]

24 For a discussion of the colonization of Querétaro and the Cadereyta and Semi-Desert regions see John Tutino, Making a New World: Founding Capitalism in the Bajío and Spanish North America, Durham, Duke University Press, 2011, 698 p.; p. 63-112; [ Links ] José Antonio Cruz Rangel, Chichimecas, misioneros, soldados y terratenientes, México, Archivo General de la Nación, 2003, 404 p. [ Links ]; Rosario Gabriela Páez Flores, Pueblos de frontera en la Sierra Gorda queretana, siglos XVII-XVIII. México, Archivo General de la Nación, 2002, 199 p. [ Links ]

25 Grijalva, Crónica..., p. 192, 217; Vergara Hernández, El infierno en la pintura mural agustina del siglo XVI, p. 91, 136. [ Links ]

26 Alipio Ruiz Zavala, O.S.A, Historia de la Provincia Agustiniana del Santísimo Nombre de Jesús de México. 2 v., Mexico, Porrúa, 1984, v. 1, CL-546, v. 2, CL-707, v. I, p. 511. [ Links ]

27 Galaviz de Capdevielle, "Descripción y pacificación de la Sierra Gorda," p. 10. [ Links ]

28 Antonio Lorenzo Monterrubio, La irrupción de La Soledad Chichicaxtla, Hidalgo: Arquitectura del siglo XVI. México, INAH, 2003, 308 p.; p 88. [ Links ] The quote in Spanish reads: "De ahi en pocos dias (fines de 1568) se alzaron los indios de la comarca y provincia de Xalpa, de que antes estaban sujetos y tributarios, y quemaron el pueblo principal de Xalpa, que era (de) Mexicanos, y quemaron el monasterio y entraron a los pueblos de Jelitla y Chapuluacan y les depoblaron muchos sujetos y derribaron las Iglesias y para remedio, invió el Virrey a don Francisco de Puga, (en) su lugar (su) Teniente, con veinticuatro soldados con mucho salario y costa de S.M., y como no hizo costa de provecho dentro de diez meses, que de continuo con mucho riesgo de mi persona los sujeté y rendí y puse de paz y en obediencia a S.M., y reduje al conocimiento de Dios nuestro Señor, de cuya ley habian apostado, y redifique el pueblo de Xalpa de nuevo y hice en el un fuerte de los mejores que hay en la Nueva España, de piedra y cal, y dentro de el una Iglesia y Monasterio sin costa de S.M., cuyo edificio vale más de veinte mil pesos, lo cual hice yo por mi propia persona, con que se asegura por muchos años toda aquella tierra y los dichos pueblos de Jelitla, Chapuluacan, Acicastla y Suchitlan".

29 Ruiz Zavala, Historia de la provincia Agustíniana, v. I, p. 505. [ Links ]

30 José Alfredo Rangel Silva, "El discurso de una frontera olvidada: El Valle de Maíz y las guerras contra los "indios bárbaros, 1735-1805", Cultura y Representaciones Sociales, Mexico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, v. 2, marzo de 2008, p. 119-153; p. 123. [ Links ]

31 Zavala, "Los frailes agustinos...", Galaviz de Capdevielle, "Descripción y pacificación de la Sierra Gorda", p. 10. There are few details regarding the Augustinian misión at Xalpa Turing the seventeenth Century. A partial list of the resident missionary in charge of Xalpa can be reconstructed from the records of the chapter meetings held by the Augustinians every three years, which contained lists of the superiors of each convent who attended the meetings. There is a record of Augustinians stationed on the mission at Xalpa from 1645 to 1743, when royal officials transferred Xalpa to the jurisdiction of the Franciscans. Prior to 1645 the Augustinians stationed on Xalpa did not attend the chapter meetings, or the missionaries stationed at Xilitlán administered Xalpa as a distant visita.

32 Cruz Rangel, Chichimecas, misioneros, soldados y terratenientes, p. 297.

33 Galaviz de Capdevielle, "Descripción y pacificación de la Sierra Gorda," p. 22.

34 Gerardo Lara Cisneros, El cristianismo en el espejo indígena: Religiosidad en el occidente de la Sierra Gorda siglo XVIII, 2a. ed., Mexico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, 2009, p. 162-167. [ Links ]

35 Eleanor Wake, Framing the Sacred: The indian Churches of Early Colonial Mexico, Norman, Oklahoma, University of Oklahoma Press, 2010, CL-338, p. 62. [ Links ]

36 Luis González Obregón (paleography and preliminary note), Proceso inquisitorial del Cacique de Tetzcoco, reprint edition. México, Archivo General de la Nación, 2009, 111 p.; p. 105-108. [ Links ] According to the suma de visitas Pedro Camorano and Antonio de la Torre held Ocuila in encomienda, and the Augustinians had already established the convent there. It had 17 estancias, and a population enumerated as living in 2 509 households consisting of 1 646 married couples, 793 widoers, and 1 864 children, not counting infants being breast fed. See Paso y Troncoso, Papeles de Nueva España, p. 166-167. [ Links ]

37 Galaviz de Capdevielle, "Descripción y pacificación de la Sierra Gorda," p. 13.

38 ibid., p. 14-16.

39 Cruz Rangel, Chichimecas, misioneros, soldados y terratenientes, p. 326.

40 Galaviz de Capdevielle, "Descripción y pacificación de la Sierra Gorda," p. 19-20.

41 Cruz Rangel, Chichimecas, misioneros, soldados y terratenientes, p. 309-312.

42 Lino Gómez Canedo, Sierra Gorda: Un típico enclave misional en el centro de Mexico (siglos XVII-XVIIII), 3rd edition. Querétaro, Provincia Franciscana de Santiago, 2011, 392 p.; p. 95-105. [ Links ]

43 María Teresa Álvarez Icaza Longoria, "Un cambio apresurado: la secularización de las misiones de la Sierra Gorda, (1770-1782)", Letras Históricas, Mexico, Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, v. 3, otoño-invierno de 2010, p. 9-45. [ Links ]

44 ibid., p. 25.

45 Robert H. Jackson, "The Guaycuros, Jesuit and Franciscan Missionaries and José de Gálvez: The Failure of Spanish Policy in Baja California," Memoria Americana: Cuadernos de Ethnohistoria, Buenos Aires, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Instituto de Ciencias Antropológicas, v. 12, 2004, p. 221-233. [ Links ]

46 ibid., p. 25.

47 Joseph de la Madre de Dios Herrera, O.F.M., Santiago de Xalpan, October 14, 1758, "Razón del estado que ha tenido y tiene esta Mission de N. S. P. San Francisco del Valle de Tilaco, de indios Pames", in Gómez Canedo, Sierra Gorda..., p. 233. The original reads: "Para tenerlos quietos y que no vayan vagueando con pretexto de buscar que comer, cada día se les administra de comunidad maíz, frijol suficiente, y algunos días carne, etc."

48 Joseph de la Madre de Dios Herrera, O.F.M., Santiago de Xalpan, October 14, 1758, "Razón individual y verídica del estado de esta Mission de Santiago de Xalpan, de indios pames, sita en la Sierra Gorda", in Gómez Canedo, Sierra Gorda..., p. 235. The original reads "En lo corporal también se cuida con todo esmero, procurando el que hagan de comunidad sus siembras, especialmente de maíz y de frijol, para que tengan todo el año que comer, y diariamente se les reparte su racion muy suficiente a todos, grandes y chicos, y en los días mas solemnes se les matan algunas reses y se les da a todos carne. Tienen de comunidad el ganado suficiente, tierras y aperos necesarios para que hagan sus siembras, y acabados de la comunidad, se valen del mismo ganado para hazer sus particulares, a lo que los alientan sus Ministros".

49 For a discussion of the California mission economic system and the labor demands on the native populations see Robert H. Jackson and Edward Castillo, indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization: The impact of the Mission System on California indians, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995, p. CL-222. [ Links ]

50 José Ortes de Velasco [1748], Razón de las misiones que el Colegio de San Fernando tiene en Sierra Gorda, alias Sierra Madre, y el estado que al presente tienen, in Gómez Canedo, Sierra Gorda... , p. 215-220.

51 Gómez Canedo, Sierra Gorda..., p. 137.

52 Ibid., p. 124.

53 ibid., p. 131.

54 Robert H. Jackson, "Missions on the Frontiers of Spanish America", Journal of Religious History, Australia, Religious History Association, v. 33, September of 2008, p. 328-347; p. 344-346. [ Links ]

55 Robert H. Jackson, "Ethnic Survival and Extinction on the Mission Frontiers of Spanish America: Cases from the Rio de la Plata Region, the Chiquitos Region of Bolivia, the Coahuila-Texas Frontier, and California", The Journal of South Texas, Kingsville, Texas, South Texas Historical Association, v. 19, Spring of 2006, p. 5-29, p. 7-9. [ Links ]

56 Ibid., p. 8.

57 Robert H. Jackson, "Congregation and Depopulation: Demographic Patterns in the Texas Missions," The Journal of South Texas, Kingsville, Texas, South Texas Historical Association, v. 17, Fall of 2004, p. 6-38; p. 15-19. [ Links ]

58 For a general study of the Chaco missions see James Saeger, The Chaco Mission Frontier: The Guaycuruan Experience, Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2000, CL-266 p. [ Links ]

59 Anua del Pueblo de S[a]n Fern[and]o Desde el Ano 1753, Archivo General de la Nación, Buenos Aires, Sala lX-10-6-10.

60 Saeger, The Chaco Mission Frontier..., p. 30, 38-39, 166-167.

61 A similar pattern can be seen in Franciscan missions established among nomadic groups in Texas collectively known as the Karankawas. See Robert H. Jackson, "A Frustrated Evangelization: The Limitations to Social, Cultural and Religious Change Among the "Wandering Peoples" of the Missions of the Central Desert of Baja California and the Texas Gulf Coast", Fronteras de la Historia,, Bogotá, Colombia, Instituto Colombiano de Antropologia I Historia, v. 6, 2001, p. 7-40; [ Links ] Robert H. Jackson, "A Colonization Born of Frustration: Rosario Mission and the Karankawas", The Journal of South Texas, Kingsville, Texas, South Texas Historical Association, v. 17, Spring of 2004, p. 31-50. [ Links ]

62 Álvarez Icaza Longoria, "Un cambio apresurado...," p. 26-27.

63 Ibid., p. 28-30.

64 Joseph Francisco de Landa in Ruiz Zavala, Historia de la provincia agustiniana del Santísimo Nombre de Jesús de México, v. I, p. 532-546. [ Links ]

65 Gómez Canedo, Sierra Gorda..., p. 102.

66 Joseph de la Madre de Dios Herrera, O.F.M., Santiago de Xalpan, October 14, 1758, "Razón del estado que ha tenido y tiene esta Mission de N. S. P. San Francisco del Valle de Tilaco, de indios Pames", in Gómez Canedo, Sierra Gorda... , p. 224, 228, 231, 233, 235.

67 Jackson and Castillo, Indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization..., p. 142-168.