Introduction

In late October 2013, after a bruising two-month political battle, Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto secured legislative approval of one of his key goals, a broad-based tax reform meant to bolster revenues. The reform’s passage was a significant victory for Peña Nieto. Since 2000, when his Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) lost its 70-year lock on the executive branch, Mexican presidents had repeatedly sought to pass a revenue-raising tax reform, widely viewed as a necessary condition for reducing social inequality, strengthening public security, and allowing Mexican Petroleum (Pemex), the state oil company, to reinvest more of its profits. However, the first two presidents of the democratic era, both representing the conservative National Action Party (PAN), had failed in this task. Peña Nieto’s ability to deliver suggested that Mexico might be turning a corner.

Nevertheless, the 2013 tax reform may well prove to be of little practical significance. The bill finally approved by Mexico’s Congress was expected to raise the tax burden by only 1% of GDP (Unda, 2014: 2). Moreover, barely a week before the reform was to be implemented, the president signed decrees attenuating at least temporarily its impact on some business sectors. The left-leaning Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), which had supported the bill, accused him of gutting it after the fact (El Diario, 2013). Not surprisingly, the actual increase in federal tax revenues in 2014 was below official expectations (SHCP, n.d.).

While perhaps surprising given the furor surrounding Peña Nieto’s reform, this outcome is consistent with Mexico’s modern history, which is strewn with tax reform attempts that were defeated, diluted or failed to have the expected impact. For decades Mexico has been one of the most lightly-taxed countries in Latin America, especially compared to other relatively prosperous societies, which generally tax more heavily than poorer ones. Its current tax burden of about 12% of GDP is a third that of Brazil and less than half that of Argentina and Uruguay (CEPALSTAT, n.d.).1

In this paper, I examine the causes of Mexico’s anomalously light tax burden and explore their implications for broader discussions on the determinants of tax policy, especially the current debate on the role of economic elites.

Easily the most common explanation of Mexico’s tax exceptionalism is that it reflects the large stream of non-tax revenue from Pemex, which reduces the need for taxation (Martinez-Vasquez, 2001; Tello and Hernández, 2010). While valid to a degree, this account is incomplete. Among other shortcomings, it cannot explain the fact that Mexico’s total fiscal revenues, and not just its tax revenues, are unusually low compared to other relatively prosperous countries in the region. Other explanations offered by scholars of Mexico, highlighting the effects of inequality, tax evasion or the country’s long border with the United States, are even less satisfying, for reasons discussed below. The Mexican case is also anomalous relative to several general theories of taxation, including those focusing on development, agricultural dependence and trade openness (Rodrik, 1998; Pessino and Fenochietto, 2010).

Some recent works on Latin American taxation point to a variable, the political power resources of economic elites, whose role has not been systematically explored in the Mexican case. Curiously, however, these works arrive at sharply conflicting conclusions regarding the implications of this variable. While Fairfield maintains that the existence of a politically cohesive business elite with strong ties to parties and the state impedes revenue-raising reform, other scholars argue that largely the same conditions facilitate taxation (Lieberman, 2003; Fairfield, 2010; Fairfield. 2015; Schneider, 2012; Flores-Macías, 2014).

At least on the surface, my interpretation of the Mexican case is consistent with Fairfield’s view. I argue that the country’s tax burden is light in part because its business elites are exceptionally well organized and have close ties to a competitive, programmatic conservative party, the PAN. Time and again, businessmen have used their power to defeat or water down proposals to raise revenue.

Nevertheless, my analysis diverges from Fairfield’s in one important respect: the relationship I find between business power and policy preferences. Fairfield portrays preferences as largely fixed and focuses instead on characteristics that allow business to wield political power. As I argue below, however, the power resources of Mexican business are themselves the product of an enduring anti-state intervention ideology forged through earlier conflicts with authorities, especially during the 1930s, when elites felt profoundly threatened by Lázaro Cárdenas’ redistributive reform project. Distrust of state intervention has inspired and united business, endowing it with an impressive capacity for collective action. From this perspective, the power resources of business are less an independent variable than one that mediates between preferences and action.

In addition to clarifying the Mexican case, this emphasis on historically-constructed preferences also sheds light on why business cohesion and partisan linkages are associated with light taxation in some studies and heavy taxation in others. In countries like Mexico episodes of radical reformism have “taught” elites to mistrust the state and guard against attempts to expand it. Where such historical experiences are lacking, however, business may have a less hostile view of the public sector and, at least under certain circumstances, may be more willing to countenance tax increases.

The paper is based on both secondary sources and 22 in-depth interviews with current or former government officials, legislators, interest group leaders and tax experts conducted in Mexico City in 2014. Although I focus on Mexico, I embed my analysis of this case within the broader context of Latin America and, in particular, those countries that, like Mexico, are relatively prosperous, industrialized and urbanized.

Mexico’s Tax System in Comparative Perspective

Probably the most distinctive characteristic of Mexico’s tax system is the small amount of revenue it yields. Between 2009 and 2013 Mexico’s tax burden, including social security and subnational taxes, averaged 11.5% of GDP. This was the single lowest figure in Latin America. In comparison, the regional average without Mexico was 19.2% and the average for the other countries with a 2013 per capita GDP over US$ 10 000 was 23.5%.2

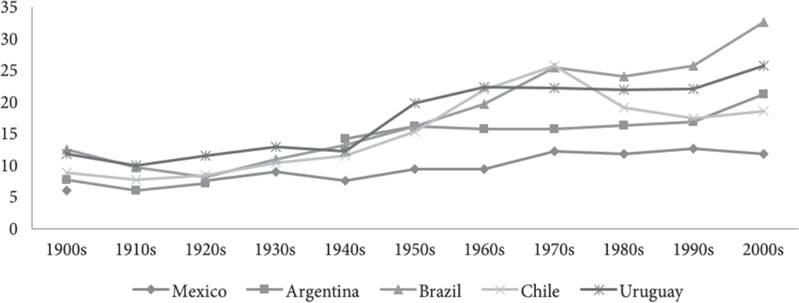

Although the gap between Mexico and the region’s most heavily taxed countries has grown in recent decades, Mexico’s status as one of Latin America’s most lightly-taxed countries is not new. Figure 1 compares the evolution of Mexico’s tax burden to that of a number of other similarly-developed countries since 1900. Despite the extraordinary chaos of Mexico’s first century as an independent nation, in the 1920s and 1930s its tax burden was not dramatically different from that of the other countries. However, Mexico began to fall behind in the 1940s. By 1960, at the latest, it was clearly a case of unusually low taxation. In fact, comprehensive regional data for 1960 suggest that Mexico had the single lowest tax burden, excluding social security contributions, in the region (ECLAC, 1978).

Sources: For 1990-2009: CEPALSTAT (n.d.). For 1980-1989: Gómez (2012). For earlier decades: Argentina: Camelo and Itzcovich (1978), Cetrángolo and Gómez (2007); Brazil: IBGE (2006); Chile: Díaz, Lüder and Wagner (2010) and World Bank (1961; 1966; 1970); Mexico: Diaz-Cayeros (2006: 36); Uruguay: García (2014).

Figure 1 Evolution of the Tax Burden, 1900-2009: Mexico in Comparative Perspective3

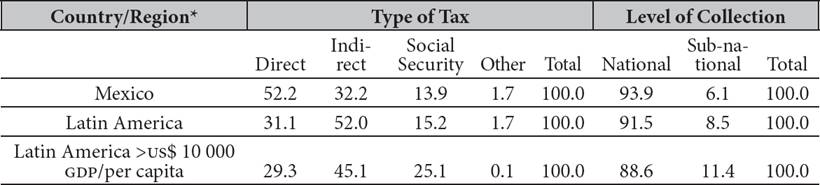

By regional standards, as Table 1 indicates, Mexico’s contemporary tax structure is skewed toward direct taxation, especially income taxation. However, this is not because its direct tax load is particularly heavy. Relative to GDP, Mexico’s direct tax revenues are about average for the region. Rather, it mainly reflects the low revenues generated by indirect taxes, such as the value-added tax (VAT). The share of social security contributions is also somewhat below the regional average, and far below the figure for the region’s most prosperous countries. In terms of the distribution of tax revenues among different levels of government, Mexico is highly centralized, but not atypical for the region.

Table 1 Tax Structure, 2009-2013: Mexico in Comparative Perspective

*Note: Haiti and Venezuela are excluded because of a lack of subnational data.

Sources: CEPALSTAT (n.d.); CIAT-IDB (2015).

Although it has tended to increase over time, the comparatively large role played by direct taxes in Mexico is longstanding. Data limitations impede a systematic cross-regional comparison, but figures from 1950, 1960 and 1970 for six Latin American countries show that direct tax revenues consistently represented a somewhat larger proportion of total tax revenues in Mexico than the others, including Argentina, Brazil and Chile (Fitzgerald, 1978: 132).4 With regard to centralization, the federal level has always predominated, but today’s acute centralization is the product of an incremental process that unfolded between the 1930s and the 1980s in which the federal government assumed tax powers previously belonging to subnational governments (Aboites, 2003; Diaz-Cayeros, 2006).

Evaluating Existing Explanations

Easily the most common explanation of Mexico’s light taxation is that it reflects the large stream of non-tax revenue from Pemex (Martinez-Vasquez, 2001; Alvarez Estrada, 2007; Elizondo, 2014). It is indeed hard to imagine that a relatively developed society like Mexico’s could sustain such a low level of taxation were it not for its plentiful non-tax revenues, which have accounted for 35-40% of fiscal revenue in recent years. Nevertheless, there are good reasons not to view natural resource wealth as anything close to a sufficient explanation.

First, Mexico’s total fiscal revenues are also quite low. Between 2009 and 2013 they averaged 19.9% of GDP, compared to a regional average (excluding Mexico) of 22.6% (CIAT-IDB, 2015). The average for the other countries with a per capita GDP over US$ 10 000 was 27.8%.5 Mexican public spending is also low. A recent in-depth study of fiscal policy in six Latin American countries found Mexico to have the lowest primary spending as a percentage of GDP, lower even than Bolivia and Peru, both much poorer countries (CEQ Institute, n.d.). In sum, Mexico is not just a low-tax country; it is a country with an underfunded public sector.

Second, Mexico’s emergence as an unusually low-tax country preceded by more than a decade its modern rise as a major oil producer. By 1960, as the previous section showed, it was clear that Mexico stood out for its low tax burden. Contemporary observers made note of that fact (Aboites, 2003). Although oil was an important source of public revenue in Mexico in the 1920s, production expanded slowly after the 1938 nationalization and Pemex’s fiscal role was minor (Farfán, 2011). It was not until the discovery of huge fields on the Gulf of Mexico’s coast in the mid-1970s that oil once again became a crucial source of public revenue. Pemex’s contribution to federal revenues jumped from just 3.9% of the total in 1972 to 38.1% ten years later (Chávez, 2005: 274).

While oil is the dominant explanation of Mexico’s low taxation, scholars have pointed to additional factors. Some claim that high income inequality inhibits taxation because only a small segment of society has the capacity to contribute significant revenue, and that segment possesses various tools, from lobbying power to legal representation, which allow it to fight off tax reforms or blunt their force (Elizondo, 2014; Tello, 2014). While this variable may help explain Mexico’s low taxation relative to wealthy countries (which tend to be more equitable), it is not convincing in the Latin American context, since Mexico’s average income Gini of 0.51 during the last decade is also about the average for the region (CEPALSTAT, n.d.).

Another claim that does not withstand comparative analysis is the argument that Mexico’s low taxation reflects the impact of widespread tax evasion (Elizondo, 2001; Bergman, 2006; Tello, 2014). Diverse measures of evasion suggest that Mexico suffers from modest levels by regional standards. A contemporary study of income tax evasion across the region found that, of the seven countries examined, Mexico had the lowest rate, lower even than Chile, often seen as the region’s most law-abiding country (Gómez, Jiménez and Podestá. 2010: 58). Similarly, estimates of VAT evasion for 14 Latin American countries show that Mexico had the second lowest rate after Chile (Gómez and Jimenez, 2012: 34). Finally, with regard to the size of the informal economy, a rough proxy for tax evasion by smaller businesses, Mexico is well below the regional average, as studies by both ECLAC and International Monetary Fund attest (Vuletin, 2008: 29; Gómez and Morán, 2012).

It has also been argued that Mexico’s light taxation reflects the impact of its long border with the United States (Elizondo, 2014). Indirect taxation is held in check by the risk that Mexicans in border areas will buy goods in the United States, either for their own consumption or illegal resale in Mexico, while direct taxation is inhibited by the ease with which well-off Mexicans can respond to the threat of a tax increase by moving assets abroad.

The evidence for these claims is at best mixed. Supporting the argument regarding indirect taxes is the fact that, until the 2013 reform, Mexico had a lower VAT rate in border areas, based on the goal of avoiding an influx of goods from neighboring US states, where sales tax rates are lower than Mexico’s VAT. However, the elimination of the border rate was expected to yield only 0.1% of GDP in revenue, so clearly the impact is minor.6 With regard to direct taxes, it is not clear why, in an era of internet transactions, Mexico’s proximity to the United States would make a major difference. It is true, as Mahon points out, that Mexico was among the Latin American countries that suffered the greatest capital flight during the 1980s debt crisis, but that category also included Argentina and Venezuela, both distant from the US border. Rather than location, what those countries shared was an overvalued exchange rate and a lack of capital controls. In Mexico the longstanding policy of allowing unlimited foreign currency purchases was meant to sooth the anxieties of a private sector that since the Cárdenas years had been deeply suspicious of the state and demanded strong reassurances that its interests would be protected (Mahon, 1996: 93-103). As will become clearer below, this account is consistent with my own argument regarding the causes of Mexico’s low tax burden.

Of course, scholars have proposed other explanations for variation in national tax burdens beyond those that have been applied to Mexico. Several involve economic variables. Economic development and involvement in international trade are typically seen as positively correlated with taxation, while inflation and farm sector size are viewed as depressing taxation (Rodrik, 1998; Mayoral and Uribe, 2010; Pessino and Fenochietto, 2010). However, Mexico is one of the most developed countries in Latin America and also has one of the most open economies among that group.7 Furthermore, its inflation has been modest and its farm sector represents a small portion of GDP.8 These conditions suggest that Mexico should have one of the heaviest tax burdens in the region.

Scholars have also argued that democracy leads to heavier taxation by allowing lower class groups to more effectively press for redistribution (Cárdenas, 2010; Besley and Persson, 2013). One might argue that Mexico’s low tax burden is related to the lateness of its democratization, which has kept the effects of democracy from fully expressing themselves. Mexico’s democratic transition occurred mainly during the 1990s, when electoral reforms were adopted that laid the groundwork for the PRI’s loss of control over Congress in 1997 and its defeat in the presidential election of 2000. In contrast, the contemporary democratic regimes in such countries as Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay emerged during the mid-1980s, and Chile returned to democracy in 1990. Colombia and Venezuela have had democracies, albeit imperfect ones, since the end of the 1950s.

Nevertheless, this explanation is unconvincing. During roughly two decades of democracy Mexico’s tax burden has remained virtually unchanged, while rising substantially in most other countries in the region (Stein and Caro, 2013). If authoritarianism had been suppressing taxation, we would have expected democracy to bring a substantial increase in revenues. Furthermore, although Mexico’s hegemonic party regime was unusually enduring, it was not as authoritarian as the military regimes that prevailed during extended periods in most other Latin American countries. It always maintained at least a semblance of electoral competition and was characterized by greater freedom of expression and association.

Tax scholars have also put forward theories focusing on the organization and influence of class actors. Some have argued that tax policy reflects the strength of organized labor or leftist parties that purport to represent low- and moderate-income groups (Cameron, 1978; Steinmo and Tolbert, 1998). Since these actors advance spending demands requiring revenue, their influence is reflected in heavier taxation. This account is echoed by Stein and Caro, who argue that control of government by left-of-center parties has been associated with bigger tax increases among Latin American countries since the 1990s (Stein and Caro, 2013).

It probably helps explain why Mexico’s taxation has remained light in recent decades, despite the transition to greater democracy. Union density has declined sharply, largely because of liberalizing economic reforms.9 While some specific groups remain highly organized, Mexican labor as a whole is weak. With regard to parties, some of the political space vacated by the PRI has been occupied by the left-leaning PRD, but the latter has never captured enough power to substantially influence national policy. It has yet to win a presidential election (although some argue that its narrow defeat in the 2006 contest resulted from fraud) and it has never controlled more than about a quarter of the seats in either house of Congress. Thus, in contrast to countries like Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, Mexico boasts neither a significantly organized labor force10 nor influential left-leaning parties11 to push for greater spending and the higher revenue it entails. In fact, a striking characteristic of contemporary Mexico is the lack of political actors able to forcefully defend public spending against private sector charges of waste and corruption.

However, the weakness of labor and labor-based parties cannot explain the fact that Mexico’s tax burden was already light before the PRI lost its hegemony. Mexico’s non-agricultural labor force was traditionally one of the more unionized in the region (Cook, 2007: 22). The Mexican peasantry was also relatively organized, especially among those who had benefitted from land reform. Most labor and peasant unions belonged to confederations with close ties to the PRI, which had been forged during the reform period under Cárdenas (Córdova, 1976; Middlebrook, 1995). Moreover, the PRI portrayed itself as a party of peasants and workers seeking to carry out the progressive promises of the Revolution. With its populist image and ties to worker organizations, the PRI could plausibly have mobilized popular support for a deepening of the reforms initiated in the 1930s, including an expansion of Mexico’s social spending, which from 1960 to 1980 was the lowest of any middle income Latin American country (Huber and Stephens, 2012: 78).

Yet, with some significant exceptions (discussed below), after 1940 the PRI shied away from mobilizing workers behind a redistributive project. Instead, it tended to use its influence to demobilize workers and facilitate a development path based on fiscal and monetary discipline and private investment (Graham, 1982; Collier and Collier, 1991). In fact, the liberalizing reforms of the 1980s and 1990s were facilitated by the party’s close ties to organized labor, which attenuated worker resistance (Murillo, 2001: ch. 5). It is thus important to understand why the PRI largely hewed to a conservative, low-tax path, when its history and political ties pointed in the opposite direction.

The answer to this question might potentially come from a more recent literature, based largely on Latin America, which argues that variation in tax policy is best explained by differences in the political organization of economic, or business elites. These works concur that where business enjoys strong encompassing organization and close ties to competitive right-wing parties and executive authorities, it is able to shape tax policy to its liking. Nevertheless, as mentioned earlier, they differ on the crucial issue of whether these characteristics impede or facilitate taxation.

In her analyses of attempts to raise direct taxes in Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, Fairfield argues that a well-organized and politically well-connected business elite hinders revenue-raising reform (Fairfield, 2010; Fairfield, 2015). Although Fairfield allows that business preferences may vary, her explanatory framework is grounded in the idea that taxation, and especially progressive taxation, contradicts fundamental business interests (Fairfield, 2015: 27). Elites will thus tend to resist taxation when they can. Therefore, the key variable affecting variance in tax policy is business power, especially power exercised through political activities, but also the power that flows from the ability to withhold investment or engage in capital flight.

Lieberman, in contrast, argues that elite cohesion helps to explain why South Africa has historically had heavier direct taxation than Brazil (Lieberman, 2003). He suggests that the threat posed by the excluded black majority united elites and made them willing to fund a system of income redistribution promoting white solidarity. In Brazil, where the racial cleavage was muted, elites were too divided to achieve such coordination. Examining the evolution of the overall tax burden in Central American in recent decades, Schneider arrives at somewhat similar conclusions regarding elite power (Schneider, 2012). He argues that taxation rose most robustly where elites were most united and exercised greatest control over the state. Likewise, Flores-Macías views elite cohesion and ties to the state as facilitating factors in the approval of a wealth tax to fund public security in Colombia (Flores-Macías, 2014).

The analysis of the Mexican experience developed below is broadly consistent with Fairfield’s view that a cohesive and well-connected business class inhibits taxation. However, it puts much more emphasis on preferences and the broader concept of ideology. Mexico’s exceptionally organized business community reflects an unusually strong anti-state intervention spirit that has motivated elites to prepare for political combat. Thus, what appears to be a difference in capabilities is more fundamentally a question of preferences, ones derived from traumatic historical experiences.

Business Power and Failed Tax Reforms

The Mexican private sector is exceptionally well organized and politically active, at least by regional standards. It has used its relative unity, capacity for collective action and ties to party leaders and government officials effectively to thwart attempts to increase Mexico’s tax burden dating back to at least the early 1960s.

Private sector elites all over Latin America have organizations to defend their collective interests. However, as Schneider has convincingly argued, Mexico stands out in terms of the representativeness and scope of its business associations (Schneider, 2002; Schneider, 2004). Unlike some other countries, Mexico’s key associations are not state-sponsored corporatist institutions. Rather, they arose from the business community itself and are funded through voluntary member contributions. Moreover, more than in any other large Latin American country, Mexico’s voluntary groups are “encompassing,” in the sense that they bring together leaders from all the major sectors to represent business as a class. Corporatist associations dominate the sectoral level, but voluntary groups, especially the Employers’ Confederation of the Mexican Republic (Coparmex), the Mexican Business Council (CMN) and the Business Coordinating Council (CCE), represent the apex of the organizational pyramid. Each has a specific character: Coparmex is a mass-membership organization, the CMN (formerly Mexican Council of Businessmen, CMHN) brings together the leaders of Mexico’s largest firms, and the CCE is a confederation of the major associations, both state-sanctioned and voluntary.

In other words, the organization of the Mexican private sector reflects a sustained bottom-up activism seldom seen in Latin America. This activist bent is perhaps most clearly embodied in the oldest of the voluntary associations, Coparmex, which boasts a large (about 36 000 firms) nation-wide membership that supports its outspoken defense of free enterprise and commitment to social conservatism (Camp, 1989: 163-166). Although Coparmex is known for being particularly combative, it is integrated into a broader network of activism that includes the other major voluntary associations, as well as most of the corporatist groups. These entities have collaborated frequently and have shared some of the same leaders (Shafer, 1973; Tirado, 1985; Luna, 1992).12 To be sure, the Mexican private sector is divided by sectoral, regional and other cleavages. However, these have not impeded it from demonstrating impressive cohesion during periods of heightened conflict with the state.

In recent decades businessmen have also enjoyed the advantage of strong ties to a competitive right-wing party, the PAN. Created in the 1930s to oppose Cárdenas, the PAN languished in relative obscurity for decades thereafter. However, it reemerged as a competitive force in the 1980s and 1990s, largely on the basis of enthusiastic grassroots business support, especially in northern Mexico (Loaeza, 1999; Mizrahi, 2003). It controlled the Mexican presidency from 2000 to 2012 and has generally been one of the two largest parties in the legislature. In comparison, most other Latin American countries, including such upper middle income societies as Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela, lack a party that is both clearly committed to defending business and capable of competing successfully in national elections (Luna and Rovira, 2014). The absence of such a party puts them at a disadvantage in terms of influencing policy (Fairfield, 2015).

Mexican governments have typically consulted frequently with key associations and firms, giving business a direct channel for influencing policy (Schneider, 2004). This tendency has led some to characterize the state-private sector relationship, especially under PRI hegemony, as a cooperative “alliance for profits” (Reynolds, 1971). However, the scholarship on business politics in Mexico shows that the relationship was considerably tenser than this expression implies.13 The presidents of the 1940s and 1950s bent over backwards to reestablish business confidence, giving the impression that the private sector and state were of one mind. This was an unstable equilibrium, however, since the extreme conservatism of public policy during this era clashed with the PRI’s claims to embody the progressive values of the revolution. As soon as the PRI sought to tilt policymaking back in a somewhat more statist, redistributive direction in the 1960s and 1970s open conflict erupted. In response to these initiatives, business strengthened its organizational network, creating the CMN in 1962 and the CCE in 1975 and breathing new life into the PAN in the early 1980s (Martínez, 1984; Tirado, 1985). It was only with the PRI’s decisive embrace of market reformism beginning in the mid-1980s that conflict would clearly subside, albeit not without residues that helped fuel the continued rise of the PAN.

Thus, a more accurate portrayal of the business-state relationship under the PRI is that the political leadership favored a more center-left policy mix in line with the party’s “revolutionary” image and popular sector ties, but was held in check by a business community that insisted on a small public sector. Even during the height of import-substitution, state intervention in Mexico was more circumspect than in some other major Latin American countries, not only in terms of fiscal policy, but in other areas as well. Compared to Brazil, for example, Mexico had a smaller public enterprise sector and weaker development bank (Graham, 1982). In pre-Pinochet Chile the state enterprise sector was also far more imposing than in Mexico (Etchemendy, 2011: 293-295). Efforts to expand the state’s role in ownership and production were consistently resisted by Mexican capitalists (Cypher, 1990). Trade protectionism was also modest by regional standards (Ros, 1993). Although the reasons for this are probably mixed, one may be that powerful business actors insisted that protectionist measures be applied in a selective, temporary fashion (Gauss, 2010: chs. 5-6).

Since the 1980s changes in the Mexican state have affected the tenor of business-state relations. The debt crisis and international pressures to liberalize essentially gutted the PRI of its revolutionary content, leading what remained of its left wing to abandon the party. From the mid-1980s until 2012 a succession of strongly pro-business governments meant that business largely got what it wanted and remained quiescent. However, the powerful private sector reaction to Peña Nieto’s modest tax reform shows (as discussed below) that business resistance to a larger state is far from a thing of the past.

Tax policy is simply the starkest and most consequential example of this broader pattern of stubborn and largely successful private sector opposition to statist initiatives. As I argue below, existing scholarship, along with evidence drawn from interviews and media coverage for recent decades, leaves little doubt that private sector opposition has played a crucial part in the demise or dilution of efforts to increase public revenues.

By the early 1960s it was clear, as discussed earlier, that Mexican tax revenues were exceptionally low, even compared to similarly-developed countries. In 1960 the government of Adolfo López Mateos began exploring the possibility of a substantial tax reform, inviting renowned British economist Nicholas Kaldor for an extended consultation (Izquierdo, 1995). Kaldor, a left-leaning Keynesian, proposed a package that would have greatly boosted revenue, while also increasing progressivity through greater income taxation. However, the government ultimately opted for a far milder reform (Aboites and Unda, 2011).

Analyses of this process generally argue that López Mateos and finance minister Antonio Ortiz Mena chose not to champion a major reform because they felt it would complicate relations with economic elites, already tense as a result of the president’s statist policy initiatives (including nationalization of the electric power industry) and his refusal to bow to US pressure to sever relations with Cuba. Major business interests reacted especially sharply to the latter, as well as official pronouncements of sympathy with Cuba’s socialist project, publicly questioning whether they reflected a desire to take Mexico in a similar direction. Seeking to quell these criticisms, the government backed down. Ortiz Mena himself offered this account (Ortiz, 1998: 156-157) and it was corroborated by another high official of the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP) (Izquierdo, 1995), as well as by scholars (Elizondo, 1994; Tello, 2011). A partially dissenting opinion is offered by Aboites Aguilar and Unda Gutiérrez, who acknowledge the pressure to placate business but argue that it was balanced by the Alliance for Progress’s endorsement of tax reform (Aboites and Unda, 2011). Instead, they stress Ortiz Mena’s personal reluctance to forge ahead with a major reform. Their view is unconvincing, however, since, by their own admission, the finance minister favored “a state strongly involved in economic development” (Aboites and Unda, 2011: 51).

Another attempt at tax reform in December 1964, at the outset of the more conservative Gustavo Díaz Ordaz presidency, yielded a potentially significant reorganization of income taxation, but its effects were blunted by a provision suspending key aspects (Aboites and Unda, 2011: 43). Though temporary, the suspension was renewed in subsequent years. This arrangement, according to an influential policymaker, was the result of negotiations between the government and the private sector, and the suspension provision was actually drafted by the latter (Solís, 1988: 42-43).

The idea of a major fiscal reform resurfaced under president Luis Echeverría, who took office in 1970 and, like López Mateos, but with greater determination, sought to take the Mexican state in a more activist and social democratic direction. Although he did increase spending quite substantially, Echeverría’s efforts to boost tax revenues were largely thwarted by business opposition. The resulting fiscal deficit marked the end of the austere “stabilizing development” policy adopted during the late 1950s.

Numerous studies document the intense rejection Echeverría’s policies engendered within the business community, manifested in sharply-worded public statements and editorials, protest events, rumor-mongering and producers’ strikes (Arriola, 1976; Martínez, 1984; Luna, 1992; Tirado, 1985; Tirado and Luna, 1995). The first major conflict involved a measure to raise a number of taxes. Although the increases were small, the measure provoked a strident outcry from business organizations, which complained that they had not been consulted (Elizondo, 1994: 166-7). In 1972, facing a rising fiscal deficit, the government advanced a broader proposal to increase income taxation. This time authorities consulted with business leaders, emphasizing the necessity of fiscal reform for stability, but the latter would have none of it (Solís, 1988: 110-116; Elizondo, 1994: 167-169). Probably fearful of provoking a major standoff, Echeverría dropped the proposal.

At least until 2013, the presidents following Echeverria did not take up again the idea of pursuing greater equity through income tax reform. However, the tax system did undergo significant reforms. Under José López Portillo (1976-1982) a VAT was introduced and collection was further centralized at the federal level. Carlos Salinas (1988-1994) introduced a corporate asset tax, and Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000) partially privatized pensions, diverting part of worker contributions into private accounts. Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) of the PAN introduced an alternative minimum income tax and a tax on bank deposits, both intended to reduce evasion and avoidance. Rates were altered on numerous occasions, with perhaps the biggest change overall being the increase in the VAT from 10% to 16%.

The private sector was intensely involved in these changes. It sought, with considerable success, to limit the extent of new revenues, even in the case of indirect taxes, reflecting a broad wariness of endowing the state with greater resources. For example, business initially opposed the VAT and later pressured successfully for the general rate to be 10%, rather than the 12.7% rate favored by authorities (Gil-Díaz and Thirsk, 1997: 297-298). Salinas faced intense resistance from some associations, especially Coparmex and the Confederación Nacional del Comercio (Concanaco), which represents commerce and services, to his asset tax. He was able to overcome it mainly because his fiscal reform also featured a reduction in income tax rates and his overall program of economic liberalization enjoyed robust business support (Elizondo, 1994: 173-183).

Asked to explain Mexico’s light tax burden, a high-ranking SHCP official during the 1980s and 1990s answered unhesitatingly that it was a consequence of business’s stubborn defense of light taxation.14 While the private sector might grudgingly accept certain revenue-raising changes to avert or attenuate fiscal crises, “it is practically a sine qua non that the tax burden not increase” on a permanent basis. Thus, efforts to raise revenue are eventually followed by ones with the opposite effect. This perspective jibes with a scholarly account suggesting that the stability of Mexico’s tax burden during these years reflected an informal state-private sector agreement allowing the former to take revenue-raising measures during times of particular need as long as they were not used to fund permanent new spending commitments (Martinez-Vasquez, 2001: 4).

Failure to increase the tax burden cannot be attributed solely to business resistance, however. President Vicente Fox (2000-2006) tried to raise revenue through a VAT reform that would have eliminated exemptions or zero rates on food, medicine and some other products, as well as the special border rate. He was thwarted mainly by the unwillingness of the PRI and PRD to accept this unpopular measure.15 However, the fact that he proposed a package grounded in regressive taxes must be attributed in large part to the PAN’s liberal, pro-business inclinations. Given the clear need for additional revenue, the opposition might well have felt obligated to approve a more balanced reform. Moreover, certain business sectors (especially food producers) lobbied hard against the measure.16

Peña Nieto’s 2013 tax reform represented somewhat of a departure from the practice of the preceding decades. Although SHCP officials met with business leaders in early 2013, representatives of the latter claim these consultations were eventually halted and that the proposal announced in September took them by surprise.17 Moreover, its emphasis on direct taxes, including a rise in the top personal income tax rate, a new tax on dividends and the erosion or elimination of corporate income tax breaks or special regimes, was deeply resented by business.18 Some sectors were also up in arms about proposed changes in indirect taxation, especially elimination of the border VAT rate. Over the next two months, the package was subject to a steady barrage of attacks from business and conservative media.

It was ultimately approved, but not without concessions reducing the expected revenue gain to a modest 1.0% of GDP. The actual increase in 2014 was 0.9% (SHCP, n.d.). As mentioned, part of the reason may have been a pair of presidential decrees signed after the law’s approval. A senior SHCP official claimed that these were not concessions to business,19 but other interviewees, including a top PRD congressman, suggested otherwise.20 In February 2014, moreover, secretary of Finance Luis Videgaray pledged that there would be no more tax increases during Peña Nieto’s term, which ends in 2018 (El País, 2014). Thus, although the 2013 reform broke the mold of state-business relations in Mexico in recent decades in some respects, it is unclear that its results will differ from those of earlier reform attempts.

History, Ideology and Business Political Organization

The correlation Fairfield posits between a cohesive, politically well-connected business sector and light taxation seems to fit the Mexican case well, but an accurate understanding of this case must underscore that these characteristics reflect deep-seated anti-state ideology born during the major redistributive conflicts of the immediate post-revolution decades and nourished by subsequent skirmishes between public authorities and the private sector. Organization, in other words, is a reflection and embodiment of preferences.

From a political perspective, what is striking about Mexican business is not just how organized it is, but how deeply it is imbued with a free market, anti-state ideology. The clearest example is Coparmex, which virtually since its birth in the late 1920s has propagated a consistent set of economically liberal, socially conservative ideas and sought to cultivate leaders capable of disseminating them. In its strongly ideological worldview and abiding emphasis on grassroots participation, it is more reminiscent of a social movement organization than an interest group. Drawing on extensive comparative research, Schneider argues that Coparmex’s combination of mass membership and longstanding ideological commitment is “unique” in Latin America (Schneider, 2004: 67).

Although an organization of national scope, Coparmex has traditionally been closely associated with the tightly-knit elite of the northern city of Monterrey, capital of the state of Nuevo León and a major manufacturing pole. Perhaps even more than Coparmex, which they largely created, the “Monterrey Group” is famed for its intransigent defense of free enterprise (Saragoza, 1988; Gauss, 2010). Coparmex and the Monterrey Group played pivotal roles in virtually every significant confrontation between the private sector and the state since the 1930s. The firms associated with them have not been above exploiting public subsidies and rents, but as collectivities they have fought to limit state economic involvement. Even trade protection was questioned on the grounds that it inhibited development by “eliminating free and fair competition and abrogating the individual rights of private property owners” (Gauss, 2010: 220-221).

Although the Monterrey industrialists are not as prominent today as they once were, the Monterrey Group and Coparmex have played crucial roles in constructing the institutions that represent Mexican business. They were instrumental in founding the CMN, in response to the sometimes tense relationship with López Mateos, as well as the CCE, which emerged as a result of the confrontation with Echeverría (Shafer, 1973; Luna, 1992; Schneider, 2002). Business leaders from Monterrey have led all three associations, and individuals who have led Coparmex have also presided over CCE and Concanaco. The Monterrey-Coparmex complex, furthermore, played a key role in the emergence of the PAN as a competitive party in the 1980s and 1990s by mobilizing business support. For example, Manuel Clouthier, the PAN’s 1988 presidential candidate, had been president of Coparmex and initially rose to prominence through his student activism at the Instituto Tecnólogico de Monterrey, a private university created to counter leftist influences in the public universities (Babb, 2005).

While their sharply ideological worldview and contentious approach to politics is not the norm, Coparmex and the Monterrey Group would have been unable to exercise such an important leadership role had their discourse not struck a chord with many other businesspeople. Indeed, scholars of Mexican business have often argued that its predominant ideological perspective, especially among large firms, involves principled opposition to state intervention. Shafer notes that “the legendary business conservatism of Nuevo León has always had plenty of counterparts elsewhere” (Shafer, 1973: 105). Likewise, Martínez stresses the “historical paranoia” of the bourgeoisie about state intervention, which makes it “hypersensitive to the least expansion of the state presence in economic activities, and even more so to reformist projects” (Martínez, 1984: 81). Luna, while acknowledging the importance of other influences, such as Catholic social conservatism, maintains that “the influence of liberal theorists on the configuration of business ideology has been determining” (Luna, 1992: 28-29).

Admittedly, there has long been a faction of business, comprised largely of smaller manufacturing firms, whose leaders explicitly endorse state intervention. It is associated mainly with Cámara Nacional de la Industria de Transformación (known as CNIT or, more recently, Canacintra), a corporatist entity created by the state in 1941, which remained staunchly loyal to the PRI under the dominant party regime. However, even under during this era, Canacintra had limited influence in the business community. For example, a 1973 study pointed out that “CNIT doctrine has utterly ‘failed’ to win the hearts of Mexican business to it, and it has had no effect on private enterprise attitudes toward government intervention, except possibly to make them more suspicious of government” (Shafer, 1973). Since democratization, moreover, Canacintra has lost even more ground to big business (Shadlen, 2006).

Strong anti-government sentiment has its roots in the attempts to implement the redistributive, nationalist promises of the Mexican Revolution, especially under Cárdenas. By profoundly threatening property rights and employer control over the workforce, but not actually destroying the private sector, these reforms unintentionally prompted the emergence of anti-state sentiments and a collective identity based on stubborn resistance to the state.

Some historical analyses diminish the extent of change that occurred during the Mexican Revolution and its aftermath, perhaps because the policies subsequently adopted under the PRI were generally conservative (Anguiano, 1975). However, by the standards of the time, the reforms of the 1930s were genuinely radical (Córdova, 1976; Knight, 1994; Gilly, 2013). Cárdenas’s agrarian reform, which expropriated 18 million hectares of private land, was easily the largest in Latin America up to that time. His dramatic expropriation of foreign oil companies in 1938 was, likewise, the first major nationalization in the region. Cárdenas’ decisive support for unionization and strikes also brought a major change in labor rights in Mexico. These moves, following on milder land and labor reforms in the previous decade, were rooted in the 1917 Constitution, which included strong social provisions and vested ultimate ownership of land and subsoil rights in the state.

The significance of these changes was magnified by the fact that they played out against an international backdrop of growing socialist influence, and the Cárdenas government was by no means free of such influences. Though the president himself was not an avowed socialist, some of his closest allies were (Hamilton, 1982: 280). Moreover, his educational policy, which sought to wrest power from the Catholic Church, explicitly promoted socialist values.

Not surprisingly, the government provoked a strong reaction from business and other conservatives. In the forefront were the industrialists of Monterrey, then the hub of the manufacturing sector. Their first major salvo against growing state encroachment had been in 1929, when they organized Coparmex to fight a proposed labor reform. The conflict escalated dramatically under Cárdenas, however. They struck back at his “communist” initiatives with sharp public criticisms, protest marches, lockouts, and support for the fascist Gold Shirts and Sinarquistas (Nuncio, 1982; Saragoza, 1988). It was in the heat of this confrontation that the elites of Monterrey and Nuevo León forged the distinctive identity that would mark them thereafter, one that blended preexisting notions of regional exceptionalism with a militant defense of free enterprise and a bold willingness to oppose national authorities (Snodgrass, 2006).

The Monterrey industrialists played an especially prominent role in this struggle, but they were not alone. In urban and rural areas alike, elites mobilized to defend their property and prerogatives through both peaceful and violent means. These clashes “resulted in an increasing polarization and reaction by the affected sectors and by the capitalist class as a whole” (Hamilton, 1982: 215). The fact that redistributive reforms were combined with anti-clericalism forged a growing alliance between business and the Church (Tirado, 1985). As the end of Cárdenas’ term approached, conservatives prepared for the 1940 elections. Sectors of business supported the creation of the PAN, and at least initially provided backing for opposition presidential candidate, Juan Andreu Almazán.

In the face of this resistance, Cárdenas eventually began to back off his radical reformism, probably because he feared a reversal of his previous achievements, perhaps through a military coup or armed uprising (Michaels, 1970; Hamilton, 1982: 260). The shift was deepened during the 1940s, as the ruling party compensated the owners of expropriated oil companies, slowed land reform, discouraged strikes and suppressed wage growth.

Although the ruling party (which changed its name to PRI in 1946) tried hard to reassure the private sector of its good intentions, it was unable to reverse the anti-state sentiment fomented during the 1920s and 1930s (Shafer, 1973; Gauss, 2010). One reason is that the conflicts of this period had given rise, especially in Nuevo León, to a new combative identity, which was a source of considerable pride and colored the worldview of many business leaders. It was institutionalized in Coparmex and PAN, organizations whose very raison d’être was to limit state interference in the economy. Although only a minority of business owners and executives were affiliated with these organizations, their ideological influence was nevertheless considerable. Even the owners of firms initially affiliated with Canacintra were often socialized into big business’s predominant anti-state mentality as their activities expanded (Cypher, 1990: 85).

This viewpoint also fed off the ongoing control of the state by Cárdenas’ party, which continued to portray itself publicly as the carrier of revolutionary values. This rhetoric, combined with their own exclusion from high government posts, helped to nurture among business elites a sense of vulnerability. For example, a wide-ranging study of business elites found that this group tended to believe, despite much evidence to the contrary, that organized labor had much more influence than they did (Camp, 1989: 122-127). Moreover, as mentioned earlier, under López Mateos and Echeverría, the priista state also undertook efforts to impart some substance to its image by returning to more left-leaning policies. Although rather mild, these initiatives had the effect of confirming to a private sector already deeply ill-disposed toward the state the correctness of its own views. The same can be said of López Portillo’s banking system nationalization. Undertaken in response to desperate circumstances by a president who had gone to considerable lengths to cultivate business confidence, this move was nevertheless widely interpreted by the private sector as symptomatic of the priista state’s hostility to free enterprise and thus served to fuel the rise of the PAN.

Three decades of liberalizing, business-friendly policymaking under both PRI and PAN governments since that time may have attenuated Mexican business’s distrust of the state to some degree, but the powerful reaction to Peña Nieto’s fairly modest tax reform in 2013 shows that it is by no means dead.

Implications for the Elite Power-Taxation Debate

In addition to clarifying the Mexican case, this emphasis on historically-constructed preferences sheds light on the ongoing debate regarding the implications of business elite political organization for taxation, helping us understand why scholars have reached such contradictory conclusions.

Part of the contrast between Fairfield’s position and that of other analysts simply reflects the partisan identity of the governments each chose to examine. In the cases explored by Lieberman, Schneider and Flores-Macías there are hardly any instances of left-party governance. In the cases explored by Fairfield, in contrast, there are many such instances, including the four Concertación governments in Chile and Kirchnerismo in Argentina (Lieberman, 2003; Fairfield, 2010, 2015; Schneider, 2012; Flores-Macías, 2014). If we assume that business is more willing to cooperate with parties and leaders to whom it has preexisting ties, then it is not surprising that Fairfield stresses business resistance to taxation and that the others find at least some instances of business acquiescence to higher taxes.

However, selection bias is not the only reason for the differing conclusions. For example, in Argentina, as Fairfield points out, a leftist governing coalition has dramatically increased the tax burden since 2003 without provoking united resistance from business. Even a much more timid effort to raise revenues in Chile or Mexico would surely have unleashed a massive counter-mobilization.

A complementary explanation relates to how elite ideology has been shaped by past conflicts with the state. In cases where the private sector has felt acutely threatened by governments willing and able to use their power to redistribute property and income, it may develop an enduring aversion to giving the public sector tools that could be used against its interests. This, as I have argued, is the case in Mexico.

It is also an accurate depiction of contemporary Chile, Fairfield’s major example of how a cohesive business elite with strong party ties has successfully combatted attempts to raise taxes. The Chilean elite was traumatized by its experiences under presidents Eduardo Frei Montalva (1964-1970) and, especially, Salvador Allende (1970-1973), who engaged in widespread expropriation and increased spending and taxation. These experiences, combined with the eventual success of General Augusto Pinochet’s liberalizing reforms, unified the elite behind the defense of a noninterventionist state. This consensus is reflected in Chile’s strong encompassing business associations and the links between business and two right-wing parties created during the 1980s. Thus, as in Mexico, the political organization of Chilean business expresses the depth of its mistrust of the state.

Nevertheless, elite cohesion and political ties may potentially emerge in other contexts in which the state does not seem so threatening. Where that occurs, elites may not have as jaundiced a view of state intervention, and the organizations linked to them may find that endowing the public sector with substantial resources helps them achieve valued goals. Two good illustration of this idea, El Salvador and South Africa, can be found in the literature on business and taxation.

El Salvador is Schneider’s key example of how cohesive and influential elites can promote increased taxation (Schneider, 2012). Since the 1980s this Central American country has seen the emergence of a new group of transnational elites with interests in finance, manufacturing and nontraditional agriculture. Through its economic power and political unity this group succeeded in marginalizing traditional agro-export elites. The latter had previously ruled the country in alliance with the military, building a state with a large repressive apparatus but minimal capacity for economic intervention. The new elites came to control the major business associations and used their dominance over the right-wing Arena party to control the state, as well. Arena held the Salvadoran presidency continually between 1989 and 2009 and consistently prevailed in the legislature in coalition with smaller parties (Schneider, 2012: 122-128).

Under Arena leadership, El Salvador’s tax burden grew by 40.6%, more than that of any other country in the region (Schneider, 2012). Although measures with substantial redistributive impact were resisted, in general Arena’s revenue-raising efforts did not face determined private sector opposition. Rather, business supported Arena’s efforts at constructing a modern, well-functioning state that could provide reasonable infrastructure and public services.

As Schneider notes, the threat posed by the leftist Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN), promoted elite unity. The FMLN had been the major guerrilla force during El Salvador’s protracted civil war, but following a 1992 peace agreement it became a party and Arena’s main electoral rival.

However, El Salvador had no real history of leftist governance, much less of a leftist government that actually implemented major redistributive change, so the country’s history provided elites with no clear example of a hostile state.21 Moreover, El Salvador’s history did provide a concrete example of a minimalist state that had failed to maintain social peace or foment sustained economic growth, so the new elites had a negative model of ineffective small government to react against. The Salvadoran case thus provides an illustration of elites who, though cohesive, had not “learned” to be especially suspicious of state intervention in the economy.

A similar point can be made about Lieberman’s portrayal of South Africa in his comparative study of taxation in that country and Brazil through the mid-1990s (Lieberman, 2003). The central argument is that the South African state imposed heavier income and property taxation because defense of the system of racial exclusion both unified white elites and made them willing to make common cause with poorer whites in order to present a united front against the black majority. Heavy direct taxation was thus part of a robust system of income redistribution operating within the white population. In Brazil, in contrast, the lack of explicit racial separation and conflict meant that elites lacked an overwhelming threat to unite them.

In other words, in South Africa the state was perceived by elites not as a potential enemy, to be treated with distrust and denied resources, but as a vehicle for enhancing racial solidarity in the face of a fundamental threat. It was not enough to increase the overall tax burden in order to modernize the state and the economy. Rather, the imperative of racial cohesion demanded that the tax system redistribute as well in order to enhance white support for the radically exclusionary Apartheid system.

Concluding Remarks

Mexico’s light taxation is a result, not only of the country’s oil wealth, but of political factors, most notably the fierce, sustained resistance of the private sector to attempts to raise taxes. While elites throughout Latin America dislike taxation, there are important differences in the extent to which they actively combat it and in Mexico resistance has been especially strong and unified. The weakness of labor and labor-based parties in recent decades has aggravated the effects of business power, but that variable cannot explain why taxation was light even during the PRI’s heyday, when the work force was better organized and Mexico was led by a nominally left-of-center party.

Thus, at one level my interpretation of the Mexican case supports Fairfield’s contention that elite political organization tends to impede revenue-raising tax reform (Fairfield 2010; 2015). However, as I have argued, it also presents a different perspective on the role of preferences in shaping business politics. While Fairfield separates preferences from power and strongly emphasizes the latter, I argue that the political preparedness of the Mexican business community is itself a function of that community’s especially strong anti-intervention ideology. That ideology is, in turn, rooted in a history of conflict with the state, especially during the 1930s, which were a kind of critical juncture in the political development of Mexican business.

Beyond shedding light on Mexico’s anomalously light tax burden, an emphasis on historically-constructed business ideology can help resolve a major paradox of the contemporary literature on Latin American taxation: the fact that a number of scholars agree that elite political organizations plays a major role in defining tax policy but disagree on whether that role is positive or negative. While that paradox is partially the result of case selection, it also reflects the ways in which business preferences regarding the size and role of the public sector are shaped by historical experience.

More broadly, this study strikes a blow in favor of the more historically-oriented, context-sensitive approach to social science that has gained proponents in recent decades.22 Rather than taking preferences as given, this approach delves more deeply into the ways in which political actors actually perceive their environment and how those perceptions are, in turn, rooted in the historical circumstances that created and shaped them over time. Such an approach is perhaps less amenable to broad theoretical generalizations, but it provides a more satisfying account of the causal processes involved in specific cases and can shed light on empirical outliers and paradoxes that would otherwise remain unexplained.

About the author

Gabriel Ondetti is Associate Professor of Political Science at Missouri State University. He has a BA in English from the University of Pennsylvania, an MA in Latin American Studies from Georgetown University and a PhD in Political Science from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His research has focused on fiscal and land rights issues in Latin America. He is currently working on a study of the political economy of the tax burden in Latin America that compares the cases of Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico. He is the author of: Land, Protest and Politics: The Landless Movement and the Struggle for Agrarian Reform in Brazil (2008); “The Social Function of Property, Land Rights and Social Welfare in Brazil” (Land Use Policy, 2016); “The Roots of Brazil’s Heavy Taxation” (Journal of Latin American Studies, 2015); and “From Posseiro to Sem-Terra: The Impact of MST Land Struggles in Pará” (Challenging Social Inequality: The Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST) and Agrarian Reform in Brazil, 2015, co-authored with José Batista Afonso and Emmanuel Wambergue).

Gabriel Ondetti es profesor asociado de ciencias políticas en la Universidad Estadual de Missouri. Es licenciado en Literatura por la Universidad de Pennsylvania, maestro en Estudios Latinoamericanos por la Universidad de Georgetown y doctor en Ciencias Políticas por la Universidad de Carolina del Norte (Chapel Hill). Su investigación académica se ha enfocado en asuntos fiscales y de derechos a la tierra en América Latina. Actualmente elabora un estudio sobre la economía política de la carga tributaria en América Latina, que compara los casos de Argentina, Brasil y México. Es el autor de Tierra, protesta y política: El Movimiento Sin Tierra y la lucha por la reforma agraria en Brasil (2008); “La función social de la propiedad, los derechos a la tierra y el bienestar social en Brasil” (Land Use Policy, 2016); “Las raíces de la pesada carga tributaria brasileña” (Journal of Latin American Studies, 2015); “De ‘ocupante’ a ‘sin tierra’: El impacto de las luchas del MST en Pará” (Desafiando la Desigualdad social: El Movimiento de Trabajadores Rurales Sin Tierra (MST) y la reforma agraria en Brasil (2015, en coautoría con José Batista Afonso y Emmanuel Wambergue).

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)