Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Investigación económica

versión impresa ISSN 0185-1667

Inv. Econ vol.69 no.271 Ciudad de México ene./mar. 2010

Foreign Direct Investment and growth in Central, Eastern and Southern Europe

Inversión extranjera directa en Europa Central, Oriental y del Sur

Elvira Sapienza*

Dipartimento di Scienze Statistiche, Faculty of Political Science, University of Napoli, < sapienza@unina.it>

Received October 2009

Accepted November 2009.

Abstract

This paper examines the role of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in promoting growth in 25 Central, Eastern and Southern European countries (CESE) using a dynamic panel approach that includes lags of involved variables to mitigate the problem of serial correlation. It adopts also a ‘general–to–specific’ approach to deal with the problem of the omitted variable and uses different estimation methods to control for heterogeneity. The main finding is that FDI has a positive and significant impact on economic growth coupled with an open economic environment.

Key words: Foreign Direct Investment, economic growth, transition economies.

Clasificación JEL:** F21,O40, P20

Resumen

Este artículo examina el papel de la inversión extranjera directa (IED) como promotora del crecimiento en 25 países de Europa Central, Oriental y del Sur (CESE, por su siglas en inglés) usando un enfoque dinámico de panel que incluye los retrasos de las variables implicadas para atenuar el problema de la correlación serial. Asimismo, adopta un enfoque de lo general a lo particular para ocuparse del problema de la variable omitida y utiliza diversos métodos de estimación para controlar la heterogeneidad. Los resultados principales son que la IED tiene un impacto positivo y significativo en el crecimiento económico aunado a un ambiente económico abierto.

Palabras clave: inversión extranjera directa, desarrollo económico, economías en transición.

INTRODUCTION

The argument that Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) plays a significant role in promoting growth has provided support for the policy stance emerged since the end of the 80s, when the majority of developing and transition countries started to introduce measures to liberalise trade and to create a favourable climate for FDI, adopting in many cases frameworks designed to attract foreign investors. FDI, in fact, is considered an important source of growth and financing for developing and transition economies as it supplements inadequate domestic resources to finance both ownership change and capital formation and helps to replace large amounts of obsolete capital accumulated during years of central planning. Moreover FDI, as stable long–term1 capital inflow, is also perceived as a catalyst of growth since it could bring technology, managerial know–how and skills necessary for restructuring firms and help local enterprises to expand into foreign markets. The role of FDI in transition countries has been emphasized by the new growth theory suggesting that it may enhance economic growth not only through capital accumulation but, also, by promoting technological change and human capital spillovers. Several theoretical arguments and abundant empirical evidence support the thesis that TNCs, when transferring knowledge capital, create positive spillovers in host countries enhancing the marginal productivity of the capital stock and thereby promoting growth In contrast, another strand of literature (Rodrik 1999; Amsden 2009), underlines the disadvantages implied by an indiscriminate openness to FDI especially when countries are not well endowed in terms of human capital, when the aim of the FDI contrasts with the development objectives of the country or when foreign affiliates operate in enclaves, where neither products nor technology have much in common with those of local firms. In such a case, the costs associated with inward FDI can largely outweigh economic gains.

Many studies (mostly cross section) have included a measure of FDI as a potential source of growth and different hypotheses concerning the association between FDI and growth have been tested either by conventional measures of FDI or by incorporating ancillary variables in the estimating equation. In this paper, following an extension of growth theory that includes trade and FDI as additional determinants of growth, we empirically examine the role that FDI played, taking into account the influence of an 'open' environment, in determining the process of economic growth. Our sample include 252 transition economies of the Central, Eastern and Southern European (CESE) region that in the last decades received substantial FDI inflows. This aggregate includes the 10 new European Union (EU) members, Balkans states and former Soviet Union republics.3 Using fixed effects, we adopt a dynamic panel data approach from 1990 to 2005. This paper builds upon some previous work, first of all, including lags of involved variables (both dependent and independent) to mitigate the problem of serial correlation. Secondly, a 'general–to–specific' approach is implemented and formal F–tests are conducted selecting the most parsimonious specification to deal with the problem of the omitted variable.

We find that exports and lagged FDI have a significant positive effect on country' economic growth while this effect is a negative one for current FDI suggesting that spillovers require time to occur.

The paper is organised as follows. The next section presents a picture of the FDI and exports trends in the region, focusing on the changes in the economic and political environment. Section III briefly surveys the theoretical and empirical literature on the topic providing motivation for our empirical results. Section IV presents the data set and the methodology adopted. Section V illustrates and discusses the main econometric results. Section VI summarises and draws conclusions.

FDI AND EXPORTS TRENDS IN CESE

In the years 1989 and 1990, most of the CESE countries started the transition from communist states to market economies and democratic governments. They set out to implement economic and political reforms, applying different strategies: increasing openness to trade, privatization of previously government–owned production, liberalizing markets and lowering the barriers to FDI to varying degrees. For the most part, they had not been FDI recipients to any important degree before 1990 but the collapse of the socialist system created several investment opportunities, especially because these economies were industrialized and could count on a relatively cheap yet highly educated workforce.

Evidence from CESE countries' data shows that the volume of trade appears to have a clear ascendant trend; total exports from and imports into these countries have doubled between 1990 and 2005. FDI inflows into these 25 countries steadily increased from about 3.3 billion USD in 1990 to about 74 billion USD in 2005, from 0.9 percent to 3.5 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) during this period. In 1990, however, the total amount of FDI inflows to CESE countries appeared smaller compared to other developing countries aggregates; in fact, CESE economies received only 1.6 percent of the global FDI inflows, while Latin America received 4.6 percent (World Bank 2006). However, by 2005, FDI inflows to CESE increased to 7.5 percent of the global FDI inflows while Latin America still received the same percentage (World Bank 2006).

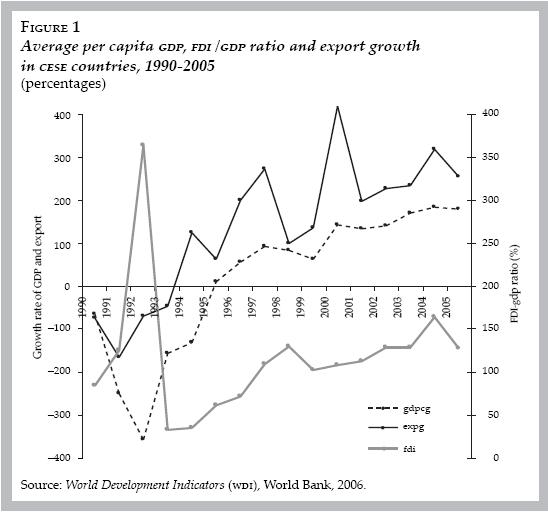

If we examine (figure 1) trends in growth of per capita real GDP, FDI/GDP ratio, and growth of exports –all averaged across the cross–section of 25 CESE countries and expressed in percentages– between 1990 and 2005, it appears that average growth rate was negative until 1995, showing an ascendant trend up to 5% in the 2005. The growth of export had initially a similar trend appearing negative although ascendant until 1993. Then, it fluctuated widely around 10%. Generally, starting from 1995, the FDI and the GDP per capita growth showed a similar behaviour. More in detail, apart from the sharp increase in 1992, the FDI share to GDP grows around 4% from 1994 to 2002 slowing down from 2003 onwards. One of the reasons could be that export oriented investments were delayed due to the downturn of the European business cycle. Uncertainties related to elections in some of the target countries like the Czech Republic and Hungary also made investors delay new investments and acquisitions.

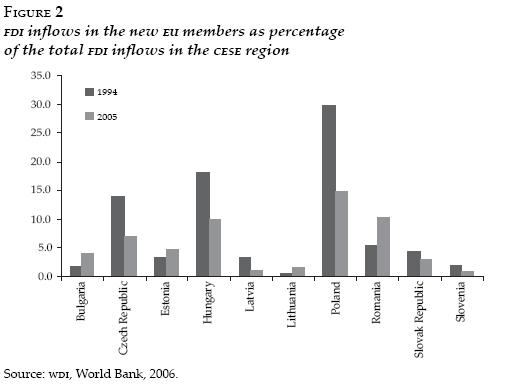

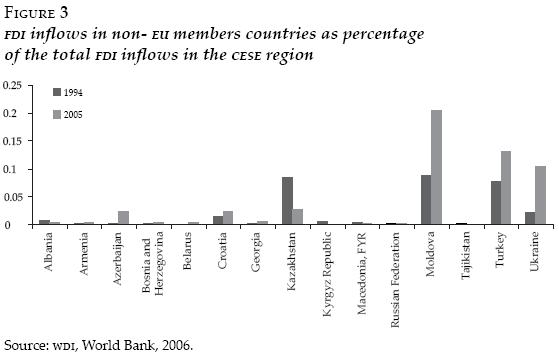

It appeared clearly, looking at the data (figures 2 and 3), that a large proportion of the total FDI inflows is concentrated in a small group of CESE whereas most other countries in the region received very limited amounts of FDI inflows. There is, in fact, wide variation across the recipient countries. For example, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland received, in 1994, 50 percent of total FDI inflows in the whole area, while Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovak Republic and Slovenia received all together about the 12% of the total. In 2005, there is an improvement in the area in terms of FDI distribution since 40% of total FDI inflows is registered by a larger group of countries: Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria and Romania. Among the other CESE economies (non EU members), a considerable percentage of the total FDI (about 22%) was recorded, in 1994, by Kazakhstan, Russian Federation and Turkey; in 2005, the percentage of Russian Federation and Turkey doubled and tripled that of Ukraine. This wide variation across the recipient countries can be explained, as many other studies have shown, by the fact that the size of the FDI inflows depends on the country characteristics (Brenton et al. 1999).

Foreign Direct Investment is not only strictly related to macroeconomic factors (economic fundamentals, market size, natural resources endowment), as pointed out by the literature (Lankes and Venables 1996; Bevan and Estrin 2000; Resmini 2000; Kinoshita and Campos 2001, among others) but also to political determinants (such as the degree of progress in transition reforms, political stability), and gravity factors (for example proximity to the European Union). FDI inflows to these countries, generally low during the first half of the '90s, have been increasing in line with improvements in all the measures of governance, particularly political stability and progress in transformation. When considering the six governance measures calculated by the World Bank4 (Kaufmann et al. 2006), the average score for the 10 new EU members countries, in 1996, was only 0.15 to reach 0.29 in the 2005 (table 1).5 The improvement has been limited for the other CESE countries. But in general, we can say that there is an enhancement all across the region although, still the overall amount of FDI, in 2005, is modest compared to the size of the countries.

Most of the progress in the governance ratings for CESE countries took place between 1996 and 2003. This improvement, intended to permit EU accession; in fact, many of these countries applied for EU membership between 1994 and 1996 and most of them entered the EU in 2004. There was, in sum, a clear positive relationship between countries' average governance scores and FDI inflows, in the second half of the 1990s. Economies with the highest governance scores, such as the Czech Republic, Hungary and Estonia had also the highest inflows while, by contrast, Bulgaria and Romania had the lowest governance scores and the lowest FDI inflows. Slovenia was an outlier, with high governance scores but only average FDI inflows because still the general investment environment is considered risky. Countries such as Albania and Macedonia have recently gained more stability but the transformation into a market economy is still incomplete and investors rarely take the risk to access these countries.

Inward FDI into the region was also encouraged by a general enhanced economic environment. This improvement is measured by the competitiveness rankings of the Global Competitiveness Reports (World Economic Forum 2006) (table 1). For 2005, the average ranking among the EU–15 was 18, where 1 represented the highest rank, while the average of the CESE countries was 59. Estonia, Czech Republic and Slovenia, were the leaders among the new EU member countries, not far behind the EU average, but the other economies ranked much lower.6 This improvement in governance and in the general climate may have helped to attract FDI inflows but it could also be that the hope of attracting FDI led to the improvements in governance.

Apart from the difference in terms of political environment, another distinction among country groups in the area can be operated on the basis of the FDI inflows character: market–seeking,7 resource seeking,8 and efficiency–seeking.9 The first group is composed, for example, of Poland and Russia with large domestic markets and by growing economies such as Croatia, Romania and Bulgaria with local markets that attract greenfield investments in the consumer goods sector. In Albania and Macedonia investments come in, through the privatisation process only to serve the local market. The second group comprises countries that attract resource seeking FDI because of their large natural resource endowment such as Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan (oil, natural gas), Tajikistan (aluminium), Kirghizstan and Ukraine (uranium). Countries such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovak Republic and Slovenia constituted the third group, where many efficiency seeking FDI entered because of the gravity factors, in the prospective membership of the European Union, especially after the initial announcement of the progress of EU accession. Bulgaria and Romania are also included in this set, since FDI entered these countries because of their abundant low wages labour. Among the main investors in these countries there are the EU/15 members, whose share is bigger compared to the rest of the region. Over the last few years, the EU/15 members have also increased their investments share in Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Moldova and Romania. An exception is constituted by Albania where Italy and Greece are responsible for almost all the investments. In the case of Italy, neighbourhood relations have also generated higher FDI shares in Poland, Romania and Slovak Republic while Germany is investing significant amounts in Croatia and Romania.

REVIEW OF THEORETICAL AND EMPIRICAL LITERATURE

The importance of trade and FDI for economic growth of transition and developing countries has been emphasized in both theoretical and empirical literature. On the one hand, apart from the traditional Ricardian argument of efficiency gain from specialization, there have been several other hypotheses put forward to argue how trade may affect growth in developing countries. In early works (e.g. Rosenstein–Rodan 1943; Nurkse 1953; Scitovsky 1954; Hirschman 1958), exports are deemed to provide the big push to break away from the vicious circle of low level equilibrium in which developing countries are often caught. Later, it is argued that exports fill in the foreign exchange gap that thwarts imports of high tech machinery needed to be competitive in the market. Endogenous growth theory emphasized the role played by exports in enhancing long–run growth by allowing a higher rate of technological innovation and dynamic learning from abroad (Lucas 1988; Romer 1986, 1989; Grossman and Helpman 1992; Edwards 1992). More recently, Coe and Helpman (1995) argue that trade enhances the spillover effects of foreign R & D on domestic productivity.

On the other hand, the role of FDI, as a composite bundle of capital stocks, know–how, and technology, has been widely recognized as a growth–enhancing factor in developing and transition countries. FDI enables host countries not only to boost capital formation but also to enhance the quality of the capital stock transferring modern technology and innovation. In fact, multinationals are assumed to use best practice technology and management which, allow them to compete successfully with local firms raising the level of competition in the host economy. However, since knowledge possesses the characteristics of public goods, the use of a new technology by one subject does not preclude others from using it, giving rise to R&D and human capital spillovers (Grossman and Helpman 1992).10 Therefore, through labour turnover or through backward and forward linkages with TNC, indigenous firms can absorb some element of this knowledge and adopt innovative products/processes. Thus, by attracting FDI, host countries hope to 'close the gap', acquiring product, process and distribution technologies, as well as management skills and market access. The theoretical ground to support the idea that FDI may enhance economic growth is offered by the Endogenous growth framework. This theory, taking into account a variety of factors enabling innovation, such as human capital accumulation and technological externalities in the development process, provides a very useful tool to analyse how the introduction of new inputs and technologies influences the production function of a given economy and how external factors affect the research efforts of economic agents and the diffusion of knowledge (Romer 1993).11 Thus, FDI has not a limited role, as in the Solow (1957) model, where it was considered only as additional capital with respect to the domestic capital level. As a vehicle of technology and cumulative R&D experience transfer, FDI, on the one hand, contributes to the stock of knowledge (innovations) enhancing the productive capacity of the economy and stimulating economic growth, on the other hand, adds to the domain of social knowledge, generating spillovers and thereby promoting further growth.

However, as Romer writes in his 1990 paper, for endogenous growth to happen some important preconditions are necessary among which there is openness to trade. Governments can make the recipient economies more appealing to foreign investment not only by offering an adequate reward to TNCs but, also, by favouring freer trade that may be supportive of growth and technological development. In fact, as Romer et al.(1991) stated, when barriers to trade are too high, and new inventions can not cross national lines, the incentive to innovate decreases suggesting a role for trade policy. There are two dimensions of the hypothesis that FDI interacts with trade having positive effect on growth. Firstly, a more liberal trade environment with export–orientation attracts higher level of FDI inflows because it not only allows foreign capital to take advantage of low cost labour in the host country but also provides access to a larger market. This, also, leads to the output expansion in internationally competitive and export oriented product lines. Moreover, the production of firms in a liberal trade regime is not limited by the size of the domestic market and has the potential to reap economies of scale through international market penetration (Kohpaiboon 2002; Nath 2005). Secondly, the neutrality of incentives,12 associated with export orientation allows exploitation of scale economies, better capacity utilization and lower capital–output ratio, making foreign capital more productive and permitting the market mechanism effectively indicate the country's comparative advantage (Edwards 1992; Salvatore and Hatcher 1991; Feder 1983). Moreover, exports promote technical innovation and dynamic learning from abroad and thereby create a more favourable environment for externalities and learning from technology spillovers associated with FDI (Worth 2004). Thus, inward FDI attracted by a liberal trade environment may conform to existing or potential comparative advantages in trade.

In contrast to the mainstream theory, another wide line of thought suggests that FDI may have a negative impact on growth for different reasons. Following Amsden (2009), it often transfers capital intensive technology inappropriate to match the factor supplies in the host countries generating displacing effects (crowd out) and distorting the development of the indigenous industry. Furthermore, the promotion of patterns of demand inappropriate to the level of development (Cook and Kirkpatrick 1995), increasing imports, may have an adverse effect on the balance of payments as the evasion of taxes on profit remission through transfer pricing (Thirlwall 1999). FDI reduces also the availability of finance or other factors for local firms because of the multinational privileged access to these resources, imposing a long term cost on the host economy (Agosin and Mayer 2000).

Following the new growth theory paradigm, there have been many attempts, over the years, to test the impact of FDI on host country economic growth. The vast literature on the topic shows, however, a contrasting evidence. On the one hand, at the macroeconomic (economy wide) level, positive effects of FDI spillovers were reported by Blomström et al. (1994) who find that, although FDI has a significant positive influence on growth rates, this influence seems to be confined to higher income developing countries. De Mello (1999), also, finds a positive correlation for selected Latin American countries but, however, the evidence would seem to suggest that, in general, a supportive economic environment is fundamental. In the study of Borensztein et al. (1998) the FDI inflows to 69 developing countries in the period 1970–89 have a positive significant influence on growth only when a certain development threshold level is achieved (in terms of educational attainment). Balasubramanyam et al. (1996), Marino (2000), Kohpaiboon (2002) find a positive growth effect of FDI associated with a liberal environment because, echoing an earlier suggestion by Bhagwati (1973), a major degree of openness is likely to provide an appropriate environment conducive to learning that must go along with the human capital and new technology infused by FDI. Rodríguez–Clare (1996) too, sustained that most of the investment activities which activate technology transfers took place in the export–oriented industries and resulted in important scale effects and externalities for GDP growth.

However, a dissenting view is echoed in Rodrik (1999) who argues that the effect of FDI on growth tends to be weak and suggests that much if not most of the correlation between FDI and a superior performance is driven by reverse causality. Hausmann and Fernandez–Arias (2000) also cast doubts on the special merits of FDI. Carkovic and Levine (2002) concluded that there is no reliable cross–country empirical evidence supporting the claim that FDI per se accelerates economic growth. Blomström and Kokko (2003) concluded from their review of the literature that spillovers are not automatic and local conditions influence firms' adoption of foreign technologies and skills.

Coming to microeconomic studies on the Foreign Direct Investment–growth impact, controversial results are also found. In terms of positive impact, the earliest contributions are the studies by Caves (1974) who examines Australian manufacturing and Blomström and Persson (1983) with data for Mexican manufacturing industries. Moreover, positive spillovers were identified by many other studies, among which there are: Sjöholm (1999) for Indonesian manufacturing, Driffield (2001) for United Kingdom (UK), Chuang and Lin (1999), Dimelis and Louri (2002) and Lipsey and Sjöholm (2001) for Taiwan, Greece and Indonesia, respectively. Kokko (1994) provided evidence of a positive relationship between the share of FDI in a manufacturing sector and the level and the growth rate of the productivity of domestic firms, since when foreign affiliates and local firms are in more direct competition with each other spillovers are more likely to be generated. Later Kokko et al. (2001) find evidence for positive productivity spillovers only from multinationals which located in Uruguay during the import substituting trade regime and no evidence for spillovers of export oriented multinationals. Thus, they argue, multinationals are more likely to rely on skills in international marketing or distribution networks rather than production technologies, implying that there is less potential for productivity spillovers.

Other studies suggest that spillovers are not significant or, that they do not take place in all industries. Haddad and Harrison (1993), in a test of the spillover hypothesis for Moroccan manufacturing during the period 1985–1989, conclude that spillovers do not take place in all industrial sectors. Aitken and Harrison (1999) examining firms data for Venezuela, fail to find evidence of economy wide spillovers from the presence of multinationals. Only firms in neighbouring activities or industries, they argue, are likely to be able to take advantage of spillovers generated by foreign subsidiaries because spillover effects tend to be localised. This is particularly true in large countries where they are likely to be confined geographically within the state or area where the FDI takes place. Cantwell (1989) claims that technology spillovers take place mainly where local firms are initially relatively strong, that large domestic firms located close to foreign firms tend to exhibit higher growth rates of factor productivity particularly in sectors where levels of technology are relatively low. These results would suggest that, first of all, the economy–wide spillover effect of a given volume of FDI is likely to be greater in geographically small countries relative to large countries and, secondly, that spillovers in large countries are relatively more sensitive to the competitive and learning capabilities of domestic firms and to the technological gap between domestic firms and TNC because, ceteris paribus, FDI in large countries is more likely to be oriented to the domestic market than in small countries. This latter point suggests that it is plausible to expect that the effect of spillovers have a greater variation across large countries compared to small ones (Yamin et al. 1999). Kathuria (2000) analysing panel data for Indian manufacturing, finds that the evidence for spillovers is weak and if inter industry spillovers occur it is rather implausible that such spillovers extend very far beyond the industry of the subsidiary. Kokko (1996) in a study of Mexican manufacturing, argues that positive spillovers are less likely in industries with highly differentiated products and large economies of scale. Foreign and local firms may use entirely different technologies when products are differentiated and economies of scale may allow the foreign affiliates to crowd out local firms from their segments of the market. He points out that, first of all, spillovers should not be expected in all kinds of industries and secondly, that they may not occur if foreign affiliates operate in enclaves, where neither products nor technology have much in common with those of local firms. From this comes that spillovers are not automatic consequences of FDI and they are less likely in industries where high foreign market shares and large productivity gaps between foreign and local firms coincide. Spillovers are not determined only by the extent of foreign presence but rather by the simultaneous interactions between foreign and local firms, in other words by competition. Only the existence of a competitive environment forces domestic firms to imitate the better technology and thus productivity increases may materialise. This may explain why spillovers do not appear in many cases.

With specific reference to transition economies, most of them are middle–income countries known for their high level of education and for their strong cultural and economic relationship with European countries. Therefore, one can imagine that they have a sufficiently good capacity to absorb knowledge spillovers. Nonetheless, the evidence concerning intra–industry spillovers in such countries is also inconclusive. Kinoshita and Campos (2002) find positive impacts of foreign investment in 27 Central Eastern countries over the period 1990–98 and also Sohinger (2005) shows that FDI with its growth–enhancing effects, has played a significant role in transition economies. Nath (2005), using panel data analysis for 13 transition countries, finds that the interaction between trade and FDI seems important for growth. Rodrik et al. (2004) find that non–economic factors, as institutions, matter for economic growth in these countries; similarly Bevan and Estrin (2000) find that political and legal issues influence foreign investment. Yudaeva et al. (2003) show that this effect is positive in the case of Russian firms, Javorcik and Spatareanu (2005) and Damijan et al. (2003) find positive FDI spillovers in Romania while, together with Djankov et al. (2000) and Konings (2001), observe negative effects for Bulgaria and Romania and no effect in Poland.

Despite the numerous alleged benefits attributed to foreign direct investment, what, clearly, the research shows is that spillovers vary systematically between countries and that the positive effects of FDI are likely to increase with the growing level of local capabilities and competition and also, with other factors that contribute to create a favourable environment. In sum, a clear significant positive impact of FDI on host countries' economic growth depends on local conditions. Finally, it is worth noting that the contrasting results could be due to the fact that, except for some recent studies that employed panel techniques, many of the others have relied upon cross–section methods to which several methodological shorthcomings are associated. Thus, the presence of diverging estimates could also be due to econometric issues13 and to differences in the sample selection procedure.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Data collection

In this paper we use macro–level data14 since, as Blonigen (2001) and Lipsey (2002) point out, they are more suitable for capturing wider spillovers on the host economy, such as those created by backward and forward linkages with domestic firms. We collected time series data, for the period 1990–2005, from the World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank. The use of a unique data source, in our opinion, should guarantee greater data homogeneity although we are aware that the World Bank dataset presents many limits in terms of data accuracy. Using the data we constructed the following variables for the empirical analysis. The growth rate of per capita real GDP15 is used as the dependent variable (GDPCG) in the growth equation.16 The explanatory variables are: the growth rate of exports17 (EXPG), used as measure of openness, the FDI inflows ratio to GDP18 (FDI) and the Gross Fixed Capital Formation share of GDP19(GFCF), used respectively as measures of the foreign and the domestic investments. The summary descriptive statistics of the relevant variables (GDPCG, GFCF, FDI, EXPG) are presented in table 2 which shows a large heterogeneity in the data. For example, in Armenia, FDI has a minimum value of 0.06 and a maximum value of 348, while in Belarus the values are 0.04 and 3.66 respectively; for the same countries the GDP per capita growth minimum and maximum values are –40.76, 14.4 and –11.59, 12.01.

THE METHODOLOGY

The general model we use to investigate the role of FDI and exports on economic growth is derived from a production function framework:

where Y is GDP per capita growth and g is a linear function of domestic investment (K), Foreign Direct Investment (F) and exports growth (X). FDI is included in the production function in order to capture externalities, learning by watching and spillover effects since it influences the growth process directly, by increasing the stock of physical capital in the recipient economy, and indirectly, by promoting technological change and inducing human capital development. Domestic investment is included as explanatory variable since the role of capital accumulation in the growth process has been stressed in early works (Harrod 1939), but also in the neoclassical growth model out of the steady state (and also in the steady state if there is a link between capital accumulation and technical progress). Exports is also introduced, as an additional factor input, into the production function, following a large number of empirical studies which investigate the export–led growth hypothesis (Feder 1983; Balassa 1985; Salvatore and Hatcher 1991; Greenaway and Sapsford 1994; Thirlwall 1999) since export orientation leads to higher factor productivity because of the exploitation of scale economies and better utilisation of capacity; furthermore, it provides access to international market and determines a higher rate of innovations. In sum, considering a large empirical literature, we can say that, in the broadest sense, these are key variables.

We use panel data estimation techniques (Baltagi 2002) with country–specific fixed effects for our empirical analysis although time invariant initial conditions have been shown to be important for growth in general (Barro 1991) and for transition economies in particular (de Mello 1997; Berg et al. 1999).20 However, given the fact that the determinants of growth in our model may take more than one year to fully exert their impact on growth, we use a dynamic specification, which includes r lags for each explanatory variable, plus possible effects of previous growth on actual growth. We proceeded from a general dynamic specification to a more parsimonious one by using appropriate tests on the degree of significance of each explanatory variable.

Then the general form of the model is represented by the following equation:

where αi, are the individual (country) effects, εit are idiosyncratic errors,  , are the parameters of interest, r = 2 and i = 1,2.. .25, t = 1990, ..., 2005.

, are the parameters of interest, r = 2 and i = 1,2.. .25, t = 1990, ..., 2005.

Among various issues and concerns about this model, the following have been formally addressed. First, although country fixed effects take care of time invariant country–specific factors, the model may still suffer from omitted variable problems if some important 'time–variant' control variables are not included. Moreover, some of these variables may be mutually correlated. Thus, while the exclusion of relevant variables may lead to the omitted variables problem, inclusion of them may give rise to the problem of collinearity. Besides, geographic contiguity and similarity in terms of political systems make it likely that some common factors can affect these countries. The obvious drawback of including many variables, given the small dimension of the time sample, is the weakness of the estimates. This is the main reason that leads us to select a parsimonious model. Second, given the differences in terms of growth experiences among the selected economies, one would expect, as appears in the descriptive statistics reported in table 2, that a remarkable variance both in time and across countries will affect the reliability of the results. This heterogeneity across country is also confirmed by the Burtlett test.

RESULTS

First of all, we estimate for the whole country and time sample, a dynamic model with two lags for both the dependent and the independent variables. The model has been estimated using 3 different methods. The 'general–to–specific' approach of model selection (Hendry 1995) leads to the elimination of the second lag, leading to results in table 3. Columns include coefficient estimates, standard errors, t–statistics and relevant diagnostics statistics obtained from the three estimation methods used. Column 1 includes estimates obtained from a Generalized Least Squares (GLS) estimation method that corrects for cross–sectional heterogeneity by using estimated cross section residual variances as weights. In column 2, we present the Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) estimates21 that corrects for both cross–sectional heterogeneity and cross–sectional correlation by using estimated cross–section residual variance–covariance weights. Column 3 contains weighted 2SLS estimates to take into account the possibility that some of the right–hand side variables could be correlated with the error terms and also to consider the presence of heteroskedasticity.

The results appear analogous under alternative estimation methods; apart from the the domestic investment (GFCF) coefficient that is significant only in SUR and 2SLS estimates, the other coefficients are significant even if some of them not always have the expected sign. It should be noted that the presence of heteroskedasticy is confirmed by the White test on GLS residuals (not reported here). Furthermore, the Hausman test we conduct identifies endogeneneity (not reported here) suggesting using the 2SLS method.

We observe that previous GDP growth exerts always a positive influence on actual GDP growth. As for FDI, the lagged coefficient is significant and positive while the current one is significant but negative. This could be accounted for the spillover effects from FDI in terms of know–how and technology, which require time to arise. Once the FDI enters a host country, the first effect could be a crowding out of the local firms with a consequent negative effect on growth. Moreover, the negative sign of FDI can also depend on the nature of the data. In fact, GDP growth can take both positive and negative values, while FDI, measured as ratio to GDP, is a variable with only positive values, then a negative correlation can arise between the two variables, especially with reference to the first years of the dataset. A further reason could be the low data quality that affects particularly the initial part of the time sample as shown in figure 1. The current domestic investment variable (GFCF) appears to exercise a positive effect in the SUR and 2SLS estimates while the lagged one shows a negative sign indicating the presence of some problem. What we said for FDI about data quality applies also to this case. Regarding the current and lagged export growth variable, this plays a positive and significant role in the growth of GDP, in all estimation methods (except the lagged coefficient in GLS and 2SLS estimates), confirming what has been suggested by the theoretical literature. In other words, the growth of export determines an increase in total factor productivity due to the exploitation of scale economies, and also an improvement in the trade balance providing access to international markets.

Among several diagnostic statistics on the residuals, we just report the R2 and the Durbin–Watson test (DW). These show similar values across the estimation methods employed, suggesting the robustness of the estimates and accepting the null hypothesis of no first order autocorrelation in the residuals, even if the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable requires a careful interpretation of this test. In fact, since we introduced lagged dependent variables in the relation to be estimated, the DW statistic could be distorted towards 2. To check this problem we use the H Durbin test.

As we argued, a considerable heterogeneity in terms of country size, degree of openness, political stability, macroeconomic development, natural resource endowment, and so on, characterises our CESE countries sample. This diversity also appears when we look at the trend of the economic variables in different countries respectively. For example, figures 4 and 5 refer to Belarus and Czech Republic; GDP growth in Belarus was negative (about –10%) until 1995, then it sharply grew in the following two years (+10%) and it rested around 8% for the remaining years. In the Czech Republic instead, the GDP increased from –10% to +5% between 1991 and 1995, then it sharply dropped to zero and from 1998 onwards it slowly started to raise to +5% for the rest of the period. In Belarus, the FDI is practically null for the whole period considered, while in the Czech Republic it slowly grows from zero to +10% until 1998, to fall, after 2002, around +5% for the rest of the period. Since this great heterogeneity can affect the results in terms of the expected signs of the parameters (especially of FDI), to verify this hypothesis we estimate the model for a sample composed only by the 10 new EU members. These countries seem more homogeneous because they experienced the same accession procedures and the related convergence policies. The results are shown in table 4 where lagged GDP growth and exports appear clearly to influence actual GDP. Current and lagged FDI coefficients are significant only in the SUR estimate while domestic investment (GFCF) is always significant and positive although the lagged coefficient continues to appear significant but negative. This unexpected result may be due not only to the poor quality of the data that particularly affects the beginning of the time sample but, also, to the decrease in the degree of freedom due to the unit sample reduction.

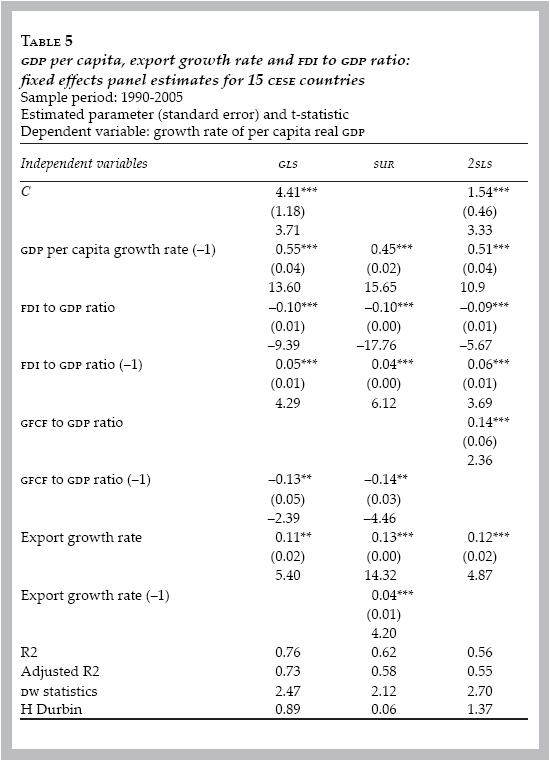

Another estimation of the model is performed using a sample that includes the 15 CESE countries not members of the EU (table 5). Again in these estimates, lagged GDP and current and lagged exports coefficients are in general positive and significant. The lagged FDI appears also highly significant and positive while the current FDI coefficient although it is highly significant does not have the expected sign probably because, as we said before, it takes time to see spillover effects from a FDI activity. Regarding domestic investment the current coefficient appears significant only in 2SLS estimates while the lagged one is always negative and significant (except in 2SLS estimates). The previous comments on the nature of the data and country heterogeneity apply also to this case.

A further hypothesis we verified is whether the lack of data, particularly relevant in the first years of the period considered, can affect our results. In order to test it, we estimated the model considering a shorter period, 1993–2005. When we considered the full countries sample (table 6), no significant improvement in the estimates appears. Lagged FDI is always positive and significant as export and the lagged GDP; current domestic investment is significant and positive in SUR and 2SLS estimates while the lagged GFCF coefficient is significant but negative as current FDI (that continue to show the wrong sign). The estimates 1993–2005 (not reported here) relative to the '10 new EU members samples' and those relative to the 'other CESE sample' are also not significantly improved.

CONCLUSIONS

The objective of this paper was, following an extension of growth theory, to evaluate empirically the impact of FDI on the rates of economic growth of 25 transition economies (CESE) for the period 1990–2005. The basic motivation for this study is that the empirical literature has had difficulties in establishing the result predicted by economic theory, namely that the effect of FDI on host country growth is positive and statistically significant. These countries have witnessed substantial increase in trade and FDI during the period examined. Applying a fixed effects dynamic panel estimation method to a data set that ranges from 1990 to 2005, this paper finds that lagged FDI has a significant positive effect on country' economic growth while this effect is a negative one for current FDI. This could be explained with the fact that spillover effects from FDI in terms of know–how and technology, require time to arise but could also be determined by the great heterogeneity that affect the data set. As expected, lagged GDP growth exert a strong influence on current GDP growth; the estimates show also a significant positive effect of exports. The same can be said for current domestic investment, although, the lagged coefficient shows, in most estimates, a negative unexpected sign suggesting the presence of some problems in the data.

When considering sub–samples as the '10 new EU members' and the 'other CESE non EU members', so as to reduce the great heterogeneity of the data, the results do not appear to improve in terms of the expected signs of the parameters but rather (as in the case of the '10 new EU members') the FDI variable becomes not significant. The same can be said in the case of the 'shorter period sample' we estimated.

In sum, our results show that lagged FDI is a crucially important explanatory variable for growth in transition economies together with previous GDP growth, domestic investment and export growth. These estimates seem robust after correcting for endogeneity and omitted variable bias in all estimation methods (GLS, SUR, 2SLS) although the great data heterogeneity suggests some caution.

Further research can investigate different country samples and different causal linkages. From an econometric point of view, it is a promising approach to employ, in the 2SLS, a different set of instrumental variables compared to those used in this paper in order to check the endogeneity of explanatory variables. In addition, the analysis of Granger causality shall contribute to a better interpretation of potential bi–directional interference between FDI and economic growth.

REFERENCES

Agosin, M. and R. Mayer, "Foreign investment in developing countries", United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Discussion Papers no. 146, February, 2000. [ Links ]

Aitken, B. and A. Harrison, "Do domestic firms benefit from Direct Foreign Investment?", American Economic Review, no. 89, 1999, pp. 605–618. [ Links ]

Amsden, A., "Nationality of firm ownership in developing countries: who should crowd out whom in imperfect markets?", in G. Dossi and J. Stiglitz (eds.), Industrial Policy and Development, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2009. [ Links ]

Balassa, B., "Exports, policy choices and economic growth in developing countries after the 1973 oil shock", Journal of Development Economics, vol. 18, 1985. [ Links ]

Balasubramanyam, VN; M. Salisu and D Sapsford, "Foreign Direct Investment and growth in EP and is countries", Economic Journal, no. 106, 1996. [ Links ]

Baltagi, B.H, Econometric Analysis of Panel Data, Second Edition, Chichester, United Kindgom, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2002. [ Links ]

Barro, R.J., "Economic growth in a cross section of countries", Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 106, no. 2, 1991. [ Links ]

Berg, A.; E. Borensztein; R. Sahay and J. Zettelmeyer, "The evolution of output in transition economies: explaining the differences", International Monetary Fund (IMF) Working Paper no. WP/99/73, 1999. [ Links ]

Bevan, A. and S. Estrin, "The determinants of Foreign Direct Investment in transition economies,", Ann Arbor, William Davidson Institute Working Paper no. 342, 2000. [ Links ]

Bhagwati, J.N., "The theory of immiserizing growth; further applications", in M. Connolly and A. Swoboda (eds.), International Trade and Money, Toronto, University Press, 1973, pp. 45–54. [ Links ]

Blomström, M. and A. Kokko, "The economics of Foreign Direct Investment incentives", National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper no. 9489, 2003. [ Links ]

Blomström, M. and H. Persson, "Foreign investment and spillover efficiency in an underdeveloped economy: evidence from the Mexican manufacturing industry", World Development, vol. 11, 1983, pp. 493–501. [ Links ]

Blomström, M.; RE. Lipsey and M. Zejan, "What explains developing country growth?", NBER Working Paper no. 4132, 1994. [ Links ]

Bloningen, B., "In search of substitution between foreign production and exports", Journal of International Economics, no. 53, 2001. [ Links ]

Borensztein, E.; J. de Gregorio and J–W Lee, "How does Foreign Direct Investment affect economic growth?", Journal of International Economics, no. 45, 1998. [ Links ]

Brenton, P. ; F. Di Mauro and M. Lücke, "Economic integration and FDI: an empirical analysis of Foreign Investment in the EU and in Central and Eastern Europe", Empirica, vol. 26, 1999. [ Links ]

Cantwell, J., Technological Innovation and Multinational Corporations, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1989. [ Links ]

Carkovic, M. and R. Levine, Does Foreign Direct Investment Accelerate Economic Growth?, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota, 2002. [ Links ]

Caves, R., "Multinational Firms, Competition and Productivity in Host–Country Markets", Economica 41(162), 1974. [ Links ]

Cernat, L. and R.Vranceanu, "Globalization and development: new evidence from Central and Eastern Europe", Comparative Economic Studies, vol. XLIV, no. 4, 2002. [ Links ]

Coe, D.T. and E. Helpman, "International R & D Spillovers", European Economic Review, vol. 39, 1995. [ Links ]

Cook, P. and C. Kirkpatrick, "Globalisation, regionalisation and third world development", University of Bradford, New Series Discussion papers no. 65, 1995. [ Links ]

Chuang, Y. and C.M. Lin, "Foreign Direct Investment, R & D and spillover efficiency: evidence from Taiwan's manufacturing firms", Journal of Development Studies, vol. 35, 1999, pp. 117–137. [ Links ]

Damijan, J.; P.M. Knell; B. Majcen and M. Rojec, "The role of FDI, R & D accumulation and trade in transferring technology to transition countries: evidence from firm panel data for eight transition countries", Economic Systems, vol. 27, 2003, pp. 189–204. [ Links ]

De Mello, L., "Foreign direct investment in developing countries and growth: A selective survey", The Journal of Development Studies, vol. 34, no. 1, 1997. [ Links ]

De Mello, L.R. Jr., "Foreign Direct Investment–led growth: evidence from time series and panel data", Oxford Economic Papers, vol. 51, no. 1, 1999. [ Links ]

Dimelis, S. and H. Louri, "Foreign ownership and production efficiency: a quantile regression analysis", Oxford Economic Papers, vol. 54, no. 3, 2002. [ Links ]

Djankov, S. and B. Hoekman, "Foreign investment and productivity growth in Czech enterprises", World Bank Economic Review, vol. 14, no. 1, 2000, pp. 49–64. [ Links ]

Driffield, N., "The impact on domestic productivity of inward investment in the UK", Manchester School, vol. 69, no. 1, 2001, pp. 103–119. [ Links ]

Edwards, S., "Openness, trade liberalisation and growth in developing countries", Journal of Economic Literature, vol. XXXI, 1992. [ Links ]

Feder, G., "On export and economic growth", Journal of Development Economics, vol. 12, 1983. [ Links ]

Greenaway, D. and D. Sapsford, "What does liberalisation do for export and growth", Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, vol. 130, 1994. [ Links ]

Grossman, G.M. and E. Helpman, Innovation and Growth: Technological Competition in the Global Economy, Boston, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1992. [ Links ]

Haddad, M. and A. Harrison, "Are there positive spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment?", Journal of Development Economics, vol. 42, 1993, pp. 51–74. [ Links ]

Harrod, R.F., "An Essay in Dynamic Theory", The Economic Journal, vol. 49, no. 193, 1939. [ Links ]

Hausmann, R. and E. Fernández–Arias, "Foreign Direct Investment: good cholesterol?", Inter–American Development Bank, mimeo, 2000. [ Links ]

Hendry, D.F., Dynamic Econometrics, Oxford, New York, Oxford University Press, 1995. [ Links ]

Hirschman, A.O., The Strateg y of Economic Development, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1958. [ Links ]

Javorcik, B.S. and M. Spatareanu, "Disentangling FDI spillover effects: what do firm perceptions tell us?", in T. H. Moran, E.M. Graham and M. Blomström (eds.), Does Foreign Direct Investment Promote Development, Washington D.C., Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2005. [ Links ]

Kathuria, V. , "Productivity spillovers from technology transfer to Indian manufacturing firms", Journal of Inter national Development, vol. 12, 2000, pp. 343–369. [ Links ]

Kaufmann, D.; A.Kraay and M. Mastruzzi, Governance Matters V: Aggregate and Individual Governance Indicators for 1996–2005, Washington D.C., The World Bank, 2006. [ Links ]

Kohpaiboon, A., Foreign Trade Regime and FDI–Growth Nexus: A Case Study of Thailand, Canberra, Research School of Pacific and Asian studies Australian National University,, 2002. [ Links ]

Kinoshita, Y. and N.F. Campos, "Agglomeration and the locational determinants of FDI in transition economies", City University of New York (CUNY) and University of Newcastle, mimeo, 2001. [ Links ]

––––––––––, "Foreign Direct Investment as technology transferred: some panel evidence from the transition economies", Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) Discussion Paper no. 3417, 2002. [ Links ]

Kokko, A., "Technology, market characteristics and spillovers", Journal of Development Economics, vol. 43, 1994, pp. 279–293. [ Links ]

––––––––––, "Productivity spillovers from competition between local firms and foreign affiliates", Journal of International Development, vol. 8, 1996, pp. 517–530. [ Links ]

Kokko, A.; R. Tansini and M. Zejan, "Trade regimes and effects of FDI: evidence from Uruguay", Weltwirtschaftlishers Archiv, vol. 137, 2001, pp. 124–149. [ Links ]

Konings, J, "The effects of Foreign Direct Investment on domestic firms: evidence from firm–level data in emerging economies", The Economics of Transition, no. 9, 2001, pp. 619–33. [ Links ]

Krkoska, L., "Foreign Direct Investment financing of capital formation in Central and Eastern Europe", European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Working Paper no. 67, 2001. [ Links ]

Lankes, H.P. and A.J. Venables, "Foreign Direct Investment in economic transition : the changing pattern of investment", Economic Transition, vol. 4, no. 2, 1996. [ Links ]

Lipsey, R.E., "Home and Host Country Effects of FDI", NBER Working Paper no. 9293, 2002. [ Links ]

Lipsey, R.E. and F. Sjöholm, "Foreign Direct Investment and wages in Indonesian manufacturing", NBER Working Paper no. 8299, 2001. [ Links ]

Lucas, R.E., "On the mechanics of economic development", Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 22, 1988. [ Links ]

Marino, A., The Impact of FDI on Developing Countries Growth: Trade Policy Matters, Italy/France, Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT) and Centre d'Etudes en Macroéconomie et Finance Internationale (CEMAFI), Universitè de Nice, 2000. [ Links ]

Nath, H., "Trade of direct investment and growth: evidence from transition economies", Working Paper Sam Houston State University, 2005. [ Links ]

Nurkse, R., Problems of Capital Formation in Underdeveloped Countries, Oxford, University Press, 1953. [ Links ]

Resmini, L., "The determinants of Foreign Direct Investment into the CEECs: new evidence from sectoral patterns", Economics of Transition, vol. 8, no. 3, 2000. [ Links ]

Rodríguez–Clare, A., "Multinationals, linkages and economic development", American Economic Review, no. 86, 1996, pp. 852–873. [ Links ]

Rodrik, D. , Making openness work: the new global economy and the developing countries, Washington D.C., The Overseas Development Council, 1999. [ Links ]

Rodrik, D.; A. Subramanian and F., Trebbi "Institutions rule: the primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development", Journal of Economic Growth, vol. 9, no. 2, 2004. [ Links ]

Romer, P.M., "Increasing returns and long run growth", Journal of Political Economy, vol. 94, 1986. [ Links ]

––––––––––, "Endogenous technological change", Journal of Political Economy, vol. 98, 1990. [ Links ]

––––––––––, "Idea gaps and object gaps in economic development", Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 32, no. 3, 1993. [ Links ]

Romer, P.M. and L. Rivera–Batiz, "Economic integration and endogenous growth", Journal of Economics, no. 106, 1991. [ Links ]

Rosenstein–Rodan, P.N., "Problems of industrialization of Eastern and South Eastern Europe", Economics Journal, vol. 53, 1943. [ Links ]

Salvatore, D. and T. Hatcher, "Inward oriented and outward oriented trade strategies", Journal of Development Studies, vol. 27, 1991. [ Links ]

Scitovsky, T., "Two concepts of external economies", Journal of Political Economy, vol. 62, 1954. [ Links ]

Sjöholm, F. , R & D, International Spillovers and Productivity Growth, Lund University, Lund Economics Studies no. 63, 1997. [ Links ]

––––––––––, "Productivity growth in Indonesia: the role of regional characteristics and Direct Foreign Investment", Economic Development and Cultural Change, vol. 47, no. 3, 1999, pp. 559–584. [ Links ]

Sohinger, J., "Growth and convergence in European transition economies: the impact of Foreign Direct Investment", Eastern European Economics, vol. 43, no .2, 2005. [ Links ]

Solow, R.M., "Technical change and the aggregate production function", Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 39, 1957. [ Links ]

Thirlwall, A.P., Growth and Development, United Kingdom, MacMillan Press, 1999. [ Links ]

World Bank, World Development Indicators, Washington D.C., 2006. [ Links ]

World Economic Forum, The Global Competitiveness Report, 2006. [ Links ]

Worth, T., "Regional Trade Agreement and Foreign Direct Investment", Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Working Paper Regional Trade Agreements and us Agriculture AER–771, 2004, pp. 77–83. [ Links ]

Yamin, M. and A. Suma , Revisiting Foreign Direct Investment and Growth: Country Size and the Scope for Economy Wide Spillovers, Manchester, Manchester School of Management, University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST), 1999. [ Links ]

Yudaeva, K.; K. Kozlov; N. Melentieva and N. Ponomaryova, "Does foreign ownership matter? Russian experience", Economics of Transition, vol. 11, no. 3, 2003. [ Links ]

* The author thanks two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments and suggestions.

**JEL: Journal of Economic Literature–Econlit.

1 In this sense it is preferable to short–term flows since it permits to avoid an increase in macroeconomic instability. See Krkoska (2001) for evidence of a strong relation between the lack of kdi, current account deficit and economic crises in central European countries.

2 The countries sample includes: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Ukraine, Uzbekistan. Bosnia–Herzegovina, Serbia–Montenegro and Turkmenistan, originally considered in a sample of 28 countries, have been removed since their time series lack data, especially in the first years of the period considered.

3 Although Turkey is not a transition country it is also included in this group for two reasons: first of all, because it belongs to the same geographic area and secondly because it will become an EU member.

4 The World Bank issued governance indicators, covering almost a decade until now.

5 Czech Republic and Slovenia scored higher than Italy and Greece not only in 1996 but also in the 2005, while Estonia, had scored higher than Greece in 1996 and higher than both in 2005.

6 In this ranking, Estonia, the Czech Republic and Slovenia outranked both Greece and Italy, and were close to Portugal and Spain.

7 Called also horizontal FDI, as it involves replication of production facilities in the host country, it aims to serve local and regional markets and its main drivers are host market size and host market growth.

8 Called also vertical or export–oriented FDI, as it involves a relocation of parts of the production chain abroad, it aims to acquire resources (natural resources, raw materials) not available in the home country.

9 This type of FDI aims to gain from the common governance of geographically dispersed activities in the presence of economies of scale and scope (low–cost labour).

10 Spillover is defined as the external effects of R & D that a firm puts in place for enhancing its own productivity compared to the other firms. Spillovers can occur both within the country and across the country (Sjöholm 1997).

11 Romer (1993) underlined that "a developing nation apart from suffering from an object gap due to the lack of valuable objects such as roads, factories, raw materials, can also suffer from an idea gap due to the fact that it has not access to the ideas used in the developed economies to generate economic value. The notion of an idea gap include something broader than a simple technology gap, some kind of economic activity that does not take place in the factories but outside. Ideas include the innumerable insights about packaging, marketing, distribution, inventory, control, payments and information system, transaction processing, quality control and worker motivation that are all used in the creation of economic value in an economy". In these ideas –based endogenous growth models–, 'ideas' (in the form of blueprints for new products or new processes) generated by investment in R & D lead to new processes and products that are used as inputs in the production of final goods, raising productivity (Romer 1990). More importantly, R & D –based innovation– is a crucial determinant of the competitiveness of firms since it does not exclusively affect the performance of those undertaking these activities but gives rise to important external effects ('R & D spillovers'). An important element of these external effects is 'knowledge spillovers', which take place if new knowledge generated by the R & D activities of one agent stimulates the development of new knowledge by others, or enhances their technological capabilities. Thus, "an idea gap can be reduced at relatively low cost by transmitting ideas and generating gains from trade and FDI shared by the supplier who already possesses the knowledge and the recipient". Since the notion of an idea gap focuses on the pattern of interaction and communication between a developing country and the rest of the world, it suggests that TNCs can play a special role as conduits of productive ideas flow across national borders (more than arms length transactions).

12 A neutral trade regime may be defined as a situation with equal incentives to domestic sales and exports. Bhagwati (1973) defined it as a regime where the effective exchange rate for exports equals the effective exchange rate for imports: EERx = EERm.

13 One problem with the interpretation of these studies is the difficulty of disentangling the direction of causation; in other words, was an economy growing faster than another because the level of FDI was higher or was the rate of FDI higher because the economy was growing faster? To the extent to which factors like the available stock of infrastructures, the market size, the presence of skilled labour, etc. are recognized to be fundamental determinants of foreign capital inflows to developing countries, we should expect that growth itself is conducive to higher levels of inward FDI. This means that a positive correlation between FDI flows and growth says nothing about the underlying causal relationship. Even when a researcher takes care to account for the endogeneity bias, it is not easy to find suitable instrumental variables, that is variables which are correlated with FDI flows but not with growth.

14 Data at the micro level were not available for the whole countries sample.

15 The World Development Indicators definition of GDP per capita growth (annual %) is: Annual percentage growth rate of GDP per capita, based on constant local currency. GDP per capita is gross domestic product divided by midyear population.

16 There have been studies that use per capita real GDP (mostly in logarithms) as the dependent variable, see Berg et al. (1999) and Cernat and Vranceanu (2002). Since our study is primarily motivated by a variant of the growth theory, the dependent variable is definitely the growth rate of per capita real GDP.

17 The WDI definition of exports of goods and services (annual % growth) is as follows: annual growth rate of exports of goods and services based on constant local currency. Aggregates are based on constant 2000 U.S. dollars.

18 The WDI definition of Foreign Direct Investment net inflows (% of GDP) is as follows: Foreign Direct Investment is the net inflow of investment to acquire a lasting management interest (10 percent or more of voting stock) in an enterprise operating in an economy other than that of the investor. It is the sum of equity capital, reinvestment of earnings, other long–term capital and short–term capital as shown in the balance of payments. This series shows net inflows in the reporting economy and is divided by GDP.

19 The WDI definition of Gross Fixed Capital Formation (% of GDP) is: Gross Fixed Capital Formation (formerly Gross Domestic Fixed Investment) includes land improvements; plant, machinery, and equipment purchases; construction of roads, railways, schools and hospitals.

20 However, previous studies (Berg et al. 1999) have argued that the effects of these initial conditions tape off as time passes. This could be another reason why they may be excluded in investigating long run growth.

21 Although we find little evidence of cross–sectional correlation, we present the SUR results for comparison.