Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Investigación económica

versión impresa ISSN 0185-1667

Inv. Econ vol.67 no.266 Ciudad de México oct./dic. 2008

Money wages in Mexico: a tale of two industries

Salarios nominales en México: una historia de dos industrias

Julio López G.*, Armando Sánchez V.**, Alberto Contreras-Cristan***, Miguel Chong***

* Facultad de Economía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), <gallardo@servidor.unam.mx>.

** Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas (IIEC), UNAM, <asanchez@vt.edu>.

*** Instituto de Investigaciones en Matemáticas Aplicadas y en Sistemas (IIMAS), UNAM, <alberto@sigma.iimas.unam.mx>, <m_a_chong@yahoo.com.mx>.

Received November 2007

Accepted May 2008.

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to identify the factors shaping the behavior of money wages in both the manufacturing sector and the maquila industry in Mexico. We study this issue with modern econometric techniques, stressing the use of multivariate econometric models congruent from statistical and theoretical viewpoints. We also introduce a new unit root test to check for the existence of unit roots in the context of a heterogeneous autoregressive process. Our empirical findings show that money wages are jointly determined in both industries, in the sense that they depend on each other; and that a similar set of conditioning variables controls their dynamics. We found that money wages in both sectors depend on the other sector's wage, on underemployment, and on the specific conditions of the sector, the latter summarized by output growth in the manufacturing sector and by productivity growth in the maquila industry.

Key words: nominal wages, manufacturing industry, maquila industry, cointegration.

Clasificación JEL: J31, L60, O14

Resumen

El objetivo de este artículo es identificarlos factores que determinan el comportamiento de los salarios monetarios en el sector manufacturero y en la industria maquiladora en México. Para ello, hacemos uso de técnicas econométricas modernas con énfasis en la especificación de modelos multivariados congruentes desde un punto de vista teórico y econométrico. Adicionalmente se introduce una prueba de raíces unitarias relativamente nueva que permite determinar la existencia de una raíz unitaria en el contexto de un proceso autorregresivo heterogéneo. Nuestros resultados empíricos muestran que la determinación de los salarios en ambos sectores está fuertemente asociada, en el sentido que los salarios en un sector dependen de los salarios en el otro sector, y que un conjunto similar de variables determina su comportamiento. Específicamente, encontramos que el comportamiento de los salarios monetarios depende del desempleo y de las circunstancias económicas de cada sector, estas últimas sintetizadas por el crecimiento del producto en la manufactura y por la productividad en el sector maquilador.

Palabras clave: salarios nominales, industria manufacturera, industria maquiladora, cointegración.

INTRODUCTION

During the last four decades the Mexican economy has gone through three distinctive stages. In the first stage, between 1977 and the first half of 1982, the state engineered an economic boom supported by huge oil exports and liberal lending from abroad. However, this situation provoked a deep crisis that took place at the end of 1982. Between 1983 and 1987 the economy stagnated with ups and downs, resulting in a significant drop of output taking place in 1986. During this second stage, significant structural reforms were undertaken at first hesitantly and later at full speed, in line with the so-called "Washington Consensus". There was an end to protection of domestic producers, support of the internal market, and government intervention; which were replaced by an opening up of the domestic market to imports, a prioritization of external over domestic sales, and a retrenching of the economic role of the state. The third stage is the one we are currently in, and can be characterized by the full realization of this new strategy. This last stage started around 1988 and can be divided into two sub-periods, with the division drawn by two major events. The first was a new crisis that erupted at the end of 1994, provoking a fall of output of about 7 percent in 1995. The second major event consisted of the adoption of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which has been changing the pattern of development of the Mexican economy.

The main objective of this paper will be to study the determinants of money wages in Mexico during what we have identified as its third and latest stage. We are interested in identifying the factors that shape money wages on a long-term basis (though the term "long-term" will be qualified later on), rather than short term. In the context of our inquiry, we will analyze and contrast the behavior of two important sectors: the manufacturing sector and the maquila (in-bond) industry. Our emphasis will be on money wages because, as Keynes argued long ago, it is money and not real wages that workers bargain for.

Usually labor market and wage studies relate the behavior of wages to the evolution of employment. According to a commonly held view, unemployment is the outcome of an exogenous (real) wage rate that exceeds the equilibrium wage rate. Under this view, which is also —but wrongly, we argue— attributed to Keynes, labor market imperfections hinder the free fall of wages that is necessary to adjust the excess labor supply.1 In our research we will not study the causality link between wages and employment, but remain within the confine of partial equilibrium analysis.

We are conscious that by narrowing the focus of our research we will not be able to answer some important questions, especially regarding the feedback between money wages with the overall economic situation. However, we believe that the points we will explore are relevant and worth careful scrutiny, especially because studies that utilize econometric methodology to analyze these issues are almost non-existent for Mexico. The main questions we would like to consider are the following: 1) Are there regularities in the functioning of the labor market which would allow the estimation of econometric models to explain the determinants of wages? 2) Have the determinants of wages remained constant during the period under consideration? 3) Are wages in the two industries functionally related? 4) Are wages in the two industries determined by a similar or radically different set of variables? We will utilize econometric techniques, with specific emphasis on Vector Autoregression (VAR) modeling and cointegration analysis, to study these questions.

In anticipation of our main conclusions, we show, with econometric inquiry, that we can give a positive answer to our first three questions, and we can also give a response to question 4. In addition, we have found that some of the extant theories of wage determination, and some ideas put forward by Keynes in The General Theory can be useful, —though not without important qualifications,— for explaining the wage setting process in a developing economy such as Mexico's.

THE LABOR MARKET: INSTITUTIONAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND

It is important first to give some information concerning the institutional arrangement of the labor market. According to a recent comparative study (Marshall, 1999) the country's wage regime is in a somewhat intermediate position in comparison with other Latin American countries.2 Mexico has a permissive right to strike, tripartite bodies that are of a permanent nature, and wage setting that is free of government control. More specific details are as follows.

Labor unionization in Mexico is low, and has been declining during the last two decades (Fairris and Levine, 2004). In the industrial sector the rate of unionization with respect to the Economically Active Population was 13.9 in 1992 and 9.8 in 2000. At the same time, the rate of unionization with respect to employment in firms where unions are legally allowed fell from 22 percent to 15 percent during this period. The widespread absence of codified rules pertaining to important aspects of the labor process is another relevant characteristic of the labor market. In 1999 changes in labor organization were codified in only 3.7 percent of manufacturing firms, while the percentages for temporary turnover of personnel and introduction of new technologies were 4.2 percent and 3 percent respectively (figures taken from Herrera and Melgoza, 2003).

On the other hand, wage bargaining has historically been decentralized in Mexico, meaning that workers traditionally negotiate at the plant or the firm level. This suggests that we can expect the evolution of wages to vary between different sectors. Nevertheless, there are common underlying forces that shape the evolution of wages, resulting from the overall economic situation, and also from institutional determinants. The most important of these institutional determinants is most likely the labor legislation, which is the same for all industries and workers. Another common determinant arises from negotiations that take place each year between representatives from the largest trade union and representatives from entrepreneur unions and the government. These negotiations have been found to bear certain weight on the settling of the average wage (López, 1999).

Wage bargaining was unconstrained until 1987 when the government implemented the so-called "Pacts" (Pactos): tri-partite agreements between representatives of workers, entrepreneurs, and the government which were established to bring inflationary pressures under control.3 According to the Pacts, workers had to limit wage demands and firms were obliged to put a cap on their profit margins, while the government agreed to restrain its expenditure. Under different names, the Pacts ruled until 1994 but failed to outlast the crisis that erupted at the end of that year.

Segmentation is another significant feature of the Mexican labor market. Particularly important to our argument is the existence of a sector which up until recently was economically and geographically separated from the rest of the economy: the maquila or in-bond industry (see Buitelaar and Padilla, 2000; Bendesky et al., 2004, for details and analysis). The history of this sector started with the 1965 maquila program in Mexico, after the United States (US) ended a previous bilateral agreement which allowed Mexican workers temporary access to the US labor market. Thus the Border Industrialization Program (Programa de Industrialización Fronteriza) was created, with the main objectives of creating jobs and attracting foreign direct investments to set up assembly operations for exports in the border zone. The program liberalized both trade and capital flows. Maquila firms (maquiladoras) could be 100 percent foreign owned at a time when foreign firms outside the program were restricted to less than 50 percent foreign ownership. They could also import input duty-free and did not face non-tariff barriers, under the condition that their output be entirely exported. Maquiladoras importing input from the US and re-exporting to the US could also benefit from Tariff Item 807.00, which permits imports of goods assembled in foreign countries containing components manufactured in the US.4 The area where maquila firms could be operated was further extended in 1971-1972 to cover the whole territory with the sole exception of industrialized areas. At present they can be located practically anywhere in Mexico.5

It is also useful to provide the reader with a long-term outlook on the labor market.6 In the following we refer to real rather than money wages, as real wages are more informative about the situation of this market under conditions of high inflation, as was the case in Mexico during part of the third stage.

The most important facts are the following. First, average wages in the maquiladora industry have at all times been lower than average wages in manufacturing; about 40 percent below in 1994, and 37 percent in 2001. (Bendesky et al., 2004). Second, wages in the two sectors show somewhat similar behavior. It appears that while neither manufacturing nor maquila workers have benefited much from any of the economic booms, they have indeed been hard-hit by the crises. Take for example average real manufacturing wages.7 They fluctuated wildly between 1976 and 1982, but grew about 15 percent overall. Subsequently, they declined about 40 percent between 1982 and 1987, recovering part (about half) of the loss by 1994, and almost falling again to their previous low by mid-1996. To date they have recovered only part of their previous loss.

Third, real wages have behaved somewhat irregularly with respect to the employment situation. Namely, they stagnated during the 1977-1982 economic and employment boom, and rose in the 1987-1994 period when the economy was growing at a somewhat moderate pace. However, manufacturing employment was declining. Only between 1997 and 2001 did wage growth coincide with employment growth (i.e., with a tightening of the labor market).

Fourth, real wages and labor productivity show a certain relation in both the manufacturing and the maquila sectors; but this association breaks down when the economy is subject to a crisis (as in 1983 and 1995). Yet since labor productivity rose at a much faster speed in the former sector, the gap between productivity and wages has widened much more in manufacturing, particularly after the 1995 crisis.8 Finally, the minimum real wage has persistently fallen along all the three stages, and in mid-2002 it was less than one third of its 1976 original level. Accordingly, the distance between the average real manufacturing wage and the minimum wage, which is paid to low-skilled workers9 and taken as a point of reference for distributing social benefits to poor segments of the population, has widened enormously during this last quarter of a century.

On the other hand, manufacturing employment has consistently declined; falling about 35 percent between its 1981 and 2001 peaks. Moreover, only during the 1977-1982 period employment grew unambiguously. Its decline began in 1982 and lasted till the first half of 1995, and growth resumption in the third stage did not bring about any increase in manufacturing employment between 1987 and the first half of 1995. On the contrary, employment in the maquila industry grew steadily and at a high rate in the entire period between 1974 and 2000, although from that year onwards it has been declining. Thus, the share of employment in the maquila industry has been growing at a fast rate, rising from 8.9 percent in 1985 to 28 percent of total manufacturing employment in 2003.

To conclude with this description, we add that open unemployment has remained stable and at a very low level. It represented 3.9 percent in 1987 and 2.7 percent in 2002 (as a share of the workforce).10 This is probably due to the lack of unemployment insurance, on the one hand, and on the other hand to the low level of family income (which does not enable the family to support its unemployed members). Due to these reasons, potential workers are often forced to accept whatever job they can get. Underemployment, which includes both open unemployment and workers employed for less than 35 hours a week, has also remained stable, though naturally at a much higher level. It represented 17 percent of the workforce in 1987, and 13 percent in 2002.

THEORETICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL ARGUMENTS

Regarding the factors that determine how wages are established, according to the dominant notion real wages are determined by labor productivity, and in the short-run they must be inversely related to the level of employment, due to the so-called law of decreasing marginal returns to labor. Besides that, since in a perfect competition situation prices rise when labor productivity falls, it was also expected that money wages would rise with employment.

Keynes, too, hypothesized that real wages would be equal to labor productivity (though he later recanted this view), but he took into consideration that wages also depend on the institutional setup and on customary norms. Later in the Keynesian camp, Phillip's (1958) famous paper stating that the degree of unemployment determines the evolution of wages, set the stage for a new dominant paradigm.

Post-Keynesian authors tend to follow the pioneering approach of Doeringer and Piore (1971), and lay emphasis on the dual or segmented structure of the labor market in today's capitalism. In this situation, the workforce in big firms in the oligopolistic sector can get wages that are higher than those prevailing in the competitive sector because of the specific requirements of capital-intensive firms, and due also to their greater bargaining power. In Seccareccia's words (2003, p. 382),

One crucial feature of the primary sector is the existence of internal labour markets that regulate internal mobility and promotion and are characterized by more rigid and hierarchical wage structures patterned along formal seniority levels. Such internal labour markets are assumed to be largely insulated from the external labour market, except at the ports of entry [...].

In contemporary literature the level of productivity is normally included as an additional argument in the wage equation (Fujii and Gaona, 2004), and the association between wages and productivity has been rationalized in two different but complementary ways. On the one hand, it is argued that due to their monopoly of specific skills or to their bargaining power, insider workers can struggle for and obtain at least a part of the extra output accruing from higher labor productivity. On the other hand, it is maintained that firms will be willing to pay their workforce a premium over and above the reservation wage in order to avert labor shirking, or guarantee an adequate productivity level, or both. It is also assumed that the premium grows when productivity rises. Finally, minimum wages are sometimes included among the arguments of the wage equation, rationalized in different ways.

In our empirical inquiry we will take into account the above-mentioned variables to model nominal wages in Mexico. We acknowledge that wage determination is a complex phenomenon, and we recognize that there are different theoretical perspectives which seldom coincide. Thus we prefer to be rather eclectic in the selection of possible variables to be included in the estimated models.

In our methodological approach the basis of any relevant conclusion must be given by a congruent econometric model from statistical and theoretical viewpoints. That is, before proceeding to attach any meaning to our estimates, we ensure that the model's statistical assumptions have been successfully validated by making use of a battery of equation and system misspecification tests. Finally, we verify that our results can be rationalized according to the economic theory by testing and imposing restrictions on the parameters of the model (Spanos, 1986, 1999).

MODELING MONEY WAGES IN MEXICO

Taking stock of the results from our previous review of factors in the current stage of Mexico's economic evolution, and of the theoretical arguments discussed in the previous section, we now carry out our econometric analysis. The objective of the econometric analysis is to answer the four questions raised in the introduction. We try to estimate econometrically valid models to explain nominal wages in the two industries, and we are mostly interested in explaining the determinants of money wages in the long-run.

First we study the statistical properties of our series. We then estimate statistically congruent VAR models, look for the existence of cointegration relations and apply impulse-response analysis to the VARS. Having found cointegration relations, we estimate error-correction models and apply Granger causality tests in order to determine the direction of causality amongst our variables.

Therefore, as a first necessary step, we present a detailed statistical analysis of the data we will utilize. Graph 1 shows the data, which consists of monthly observations of nominal manufacturing wages, nominal maquila wages, underemployment,11 gross value of production in the manufacturing sector, and labor productivity in manufacturing and in the maquila industry for the period 1990 to 2002. Note that we use the rate of underemployment (as previously defined) rather than the open unemployment rate as an argument for the wage equation, since we believe it is much more informative about the real state of unemployment.12

The graph reveals that our time series are characterized by trends, seasonal effects and outlying values, as well as cycles. Unsurprisingly, normality tests applied to the differentiated series show that the null of a normal distribution is not rejected only for underemployment. However, lack of normality is likely due in most cases to outlying values and seasonal components (Spanos,1986).

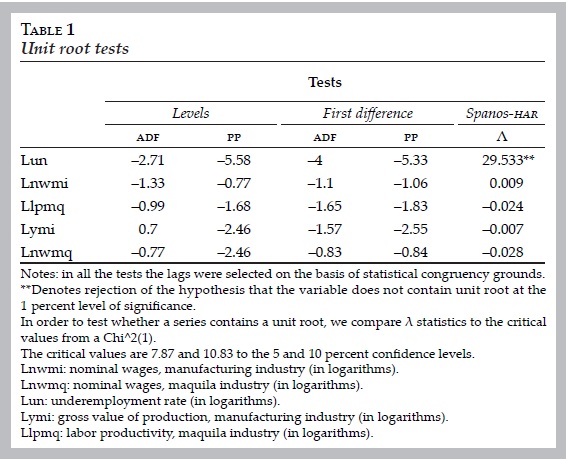

As the next step, we search for the presence of unit roots in the data in order to determine their stationary properties. Table 1 reports three different types of unit root tests: the standard Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) (1981) and Philips-Perron (PP) (1988) test, and a new test developed by Spanos (2000). The Spanos-HAR test is a likelihood ratio test for unit roots, based on a heterogeneous autoregressive process which includes a number of possible models as particular cases. Some of these can be used to nest the unit roots hypotheses. Spanos's test overcomes the lack of power featured by the Dickey-Fuller type tests in the context of alternatives close to the unit root. Table 1 shows the corresponding results.

According to the previous tests, the variables are integrated of order one, except for underemployment, which is stationary.

The aforementioned probabilistic features of our data enable us to specify a Gaussian Py —dimensional VAR(k) model for the vector of endogenous variables yt, augmented to include some additional components like exogenous variables and intervention dummies and seasonal dummies—. In general terms the expression is the following one:

Where yt is a vector of endogenous variables, zt is a vector of exogenous variables, t is a linear trend, dt is a vector of seasonal dummies and wt is a vector of intervention dummies. After an in-depth analysis of different possibilities, we were able to find VARS which were statistically congruent.13 In the case of the manufacturing sector, the VAR included manufacturing wages, manufacturing gross value of production, and maquila wages as modeled variables.14 Underemployment was included as an exogenous variable, in addition to the constant and seasonal dummies. In the case of the maquila industry, the endogenous variables were maquila wages, labor productivity in the maquila industry, and manufacturing wages, plus unemployment as an exogenous variable (as well as the constant and seasonals). In both cases the variables are in logarithms, and we used 4 lags, a value selected on the basis of statistical congruency.

The next step is to test for cointegration in a multivariate setting (Johansen, 1988). In this regard, we were actually able to find cointegration vectors for nominal wages in both the manufacturing industry and the maquila industry. Table 2 below shows the values taken by the variables in the cointegration vector.15

The goodness of fit was high in general, a result that was confirmed by inspection of the graphs comparing the actual with the estimated values for each modelled variable and for each model (graphs not included). None of the equation or vector misspecification tests rejected the underlying statistical assumptions of the models, and recursive test graphics show stability of the estimated parameters and of the equations, meaning practically no outliers were detected. We then conclude that our models are in general able to adequately simulate the actual evolution of the variables involved.

We comment now on the long-term results achieved with our econometric work (please refer to table 2). We use the expression "long-term" in a purely statistical sense, with the implication that for this period we will look for stable relationships between wages and a set of variables. According to our cointegration vectors, manufacturing wages are positively associated with maquila wages and manufacturing gross value of production with an elasticity of 0.88 and 0.1 respectively. They are negatively associated with underemployment with an elasticity of —0.29.

Conversely, maquila wages are positively associated with manufacturing wages and labor productivity with an elasticity of 1.1 and 0.18 respectively. They are negatively associated with underemployment with an elasticity of —0.025.

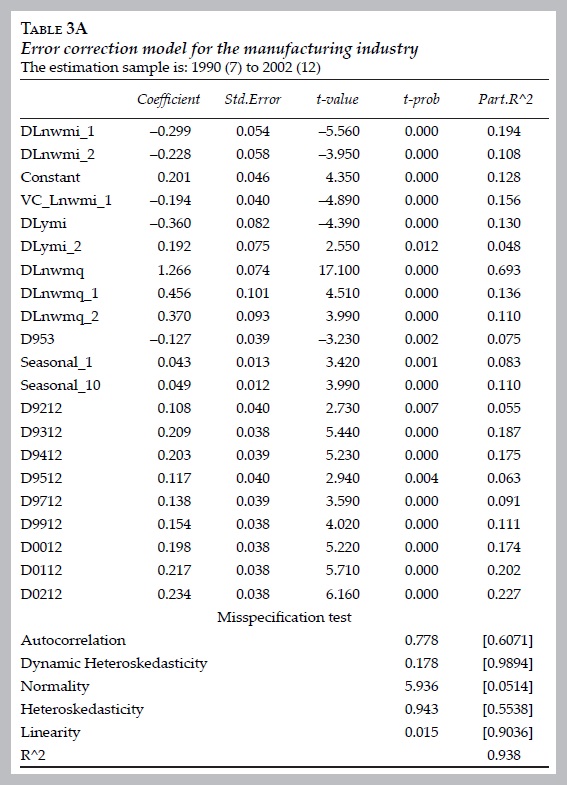

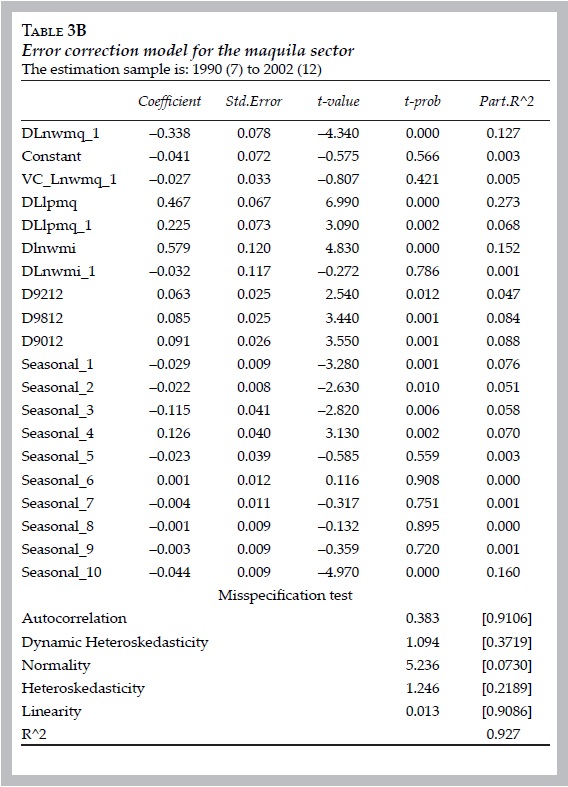

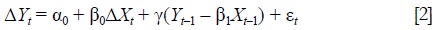

Our final econometric exercise consists in estimating two error correction models. Indeed, according to the Granger representation theorem, the existence of stable cointegration vectors for manufacturing and for maquila wages allows us to specify error-correction models for these variables. The estimation of such a model is of interest in several ways. First, it is important because we can model both the short-term dynamics in the form of lagged differences of the variables, and also the dynamics of adjustment to the long-term equilibrium, given by the error correction term. Second, with the error correction term we can also apply Granger causality analysis. The error correction specification includes the lagged differences of the exogenous and endogenous variables and the lagged cointegration vector, as follows.

Where Y is the dependent variable, X denotes the vector of independent variables. In turn, α, β and Υ are parameters. In this case we estimate an error-correction model with two lags for the variables in differences and one lag in the cointegration relationship for the manufacturing industry. Additionally, we estimate the same type of model with one lag for the differenced variables and one lag in the error correction mechanism for the maquila industry. Again, the lags were chosen based on statistical congruency grounds. Tables 3A and 3B show the results of our estimates.

The coefficient of the cointegration relationship (γ) is often interpreted as the speed of adjustment back to the long run equilibrium in this type of specifications. Our estimation results show that the coefficient of the error-correction term in our models is —0.027 for the maquila equation and —0.19 for the manufacturing equation. These results can be interpreted as follows. In the event of a one unit deviation from the long run wage in the maquila industry, a 3 percent correction occurs after one month. Yet in the manufacturing sector, a 20 percent correction occurs after the first month. In both cases the adjustment starts almost immediately, after one quarter, but the speed of adjustment back to the equilibrium is slower in the maquila sector. This fact shows that the long run behaviour of wages in those two industries is quite different. This might perhaps be attributed to the relative isolation of the maquila sector.

Regarding the influence of the short run determinants of wages in both sectors, the lagged wage of the maquila industry positively affects the manufacturing wage and vice versa. This shows that wages in both sectors are strongly linked to each other. In addition, the short-run dynamics of production seems to be inversely related to wages in the manufacturing sector. However, the productivity in the maquila sector is positively associated to the dynamic of wages in the maquila sector.

Finally, we test for Granger causality by testing the joint significance on the lagged coefficients in each of our statistically congruent Error Correction Models. The rejection of the null hypothesis in such tests implies that the lagged explanatory variables provide useful information to predict the future values of the right hand side variables. In other words, if we fail to reject the null we say that rates of growth of the lagged left side variables do not Granger cause the rates of growth of those on the right side.

From table 4 we can infer the presence of a bi-directional causality between the growth of wages in both sectors. Thus, we can suggest that wage setting in the maquila and manufacturing sectors are linked to each other. This is not a surprising fact since wages in one sector or the other might influence the wage setting process. Nonetheless, causality tests confirm that output growth in both sectors has influence on the dynamics of wages in the maquila sector as well as in the manufacturing sector. Such a finding allows US conclude that growth in both industries leads to higher wages.

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE ECONOMETRIC MODELS

We discuss now the results of our econometric work. A first important finding from our inquiry is that we were able to effectively estimate statistically valid econometric models whereby money wages can be explained on the basis of a few arguments, and the variables appearing in the two models can be given a sensible theoretical justification. We can then give a positive answer to our first question: Are there regularities in the functioning of the labor market which would allow the estimation of econometric models explaining the determinants of wages?

Moreover, in our wage equations we can also find long-term relationships. Equally important, given the stability of the recursive graphics, it seems valid to infer that the quantitative relationship between the variables involved did not significantly change. Accordingly, we can also answer our second question in the positive: have the determinants of wages remained constant during the period under consideration?

Now then, regarding our third question (are wages in the two industries functionally related?), we found that indeed wages in the two sectors are related. More specifically, in each sector the wage of the other sector appears as an important and statistically significant variable amongst the determinant of this sector's wage.

Conversely, we found that there are common factors influencing wages in the two sectors. Most notably, the rate of underemployment and the particular economic situation of the sector appear as determinants of both manufacturing wages and maquila wages. We also found, though, that in each sector the remaining variables that determine wages are different. In this sense, we can agree that the wages in the two industries are determined by some common, but also by a somewhat different set of variables (in answer to our fourth question: are wages in the two industries determined by similar or by a radically different set of variables?).

We will now carry out a more detailed discussion of the economic implications of our econometric results. Let us begin with our last point. The cointegration vectors show a close interrelationship between both sectors, in the sense that when wages grow in one industry, they also tend to grow in the other.16 Thus, a 10 percent rise of maquila wages tends to stimulate a rise of 8.8 percent of manufacturing wages, while a rise of manufacturing wages of 10 percent tends to stimulate an increase in maquila wages of about 11 percent. Thus, the parameters linking the other sector's wage to this sector's wage do not appear to be extremely different. The (fairly small) overreaction of wages in the maquila industry to wage changes in the manufacturing industry is possibly explained by the lower level of average maquila real wages vis-à-vis the level of average real manufacturing wages, and the consequent struggle of maquila workers to close that gap.

In any event, our findings about the influence of the other sector's wage in each sector's wage equation lends support to an important aspect of wage bargaining put forward in The General Theory, though in a very different socioeconomic context from the one for which it was originally formulated. This is an aspect which has seldom received much attention in contemporary literature. Keynes states that:

[...] any individual or group of individuals, who consent to a reduction of money-wages relatively to others, will suffer a relative reduction in real wages, which is a sufficient justification for them to resist it [...].

In other words the struggle about money-wages primarily affects the distribution of the aggregate real wage between different groups [...]. The effect of combination on the part of a group of workers is to protect their relative real wage (Keynes, 1980, p. 14).

We must add that the wage level that workers were able to negotiate in other sectors gives a hint as to the wage level that the government, business leaders, or both, are willing to accept as a basis to fix, for example, manufacturing wages.

Our second result is that higher underemployment seems to negatively affect the level of money wages in both sectors. Moreover, it is important to note that the effect of underemployment on wages seems to be stronger in the manufacturing sector, where a 10 percent rise in underemployment tends to cause almost 3 percent fall in wages. In contrast, in the maquila industry the fall is only about 0.25 percent. This relative imperviousness of maquila wages with respect to the situation of the labor market probably has to do with the geographical isolation of the maquila firms, which are mostly located in Mexico's northern border. Another reason is likely to be the greater autonomy of maquila firms, with respect to Mexico's business cycle, because they sell their production abroad in a market which is less volatile than the domestic one.17 Accordingly, the situation of the domestic labor market is likely to exert a smaller influence on the maquila labor market.

Third, according to our estimates, it appears that the particular conditions in each industry tend to influence the level of that industry's wage. More specifically, a higher gross value of production in manufacturing tends to raise manufacturing wages. Higher labor productivity in the maquila industry has a positive impact on maquila wages.

The association between wages and the gross value of manufacturing production can be rationalized with two different, but not contradictory arguments. The first argument suggests that when firms attain higher production and sales, they are willing to accept higher wage demands because profits are also higher. But it may also imply that higher manufacturing wages bring about higher domestic demand, stimulating output expansion. This second rationalization, however, cannot be adequately discussed within the framework of our inquiry, because we have carried out our analysis within the confine of partial equilibrium analysis, where the feedback from higher wages to (higher?) demand is ignored.

The other argument is that the positive association between productivity and wages in the maquila industry can be rationalized with the notion that firms can afford to pay higher wages without jeopardizing profits when labor productivity increases.18

In any event, the associations between wages and output found in the manufacturing industry, and between wages and productivity found in the maquila industry, tend to support the insider theory of wages. That is, insider workers in Mexico seem to be able to reap part of the beneits of higher output and sales or of higher productivity. We consider this to be a relevant finding, because the insider theory of wages was originally proposed with developed capitalist economies in mind, where unemployment tends to be relatively lower. Our result suggests that even in a situation where a large pool of unemployed or underemployed workforce exists, as in Mexico, insider workers have a certain bargaining power.

Another interesting finding of our estimates is that prices are absent as an argument of the wage equation in both of the two sectors under inquiry. This appears at first sight intriguing because we know that, especially in an inflationary environment such as Mexico's, expectations of inflation are taken into account by workers in their wage negotiation. It is usually taken for granted that these expectations are based on past inflation. Yet we think that this puzzle can be explained once we take into account that we are dealing here with a long-term relationship, and not with a short-term adjustment. In this context, we can relate this finding to the first result already referred to. As Keynes forcefully pointed out, in an uncertain situation agents rely on conventions in order to make decisions that involve the unknown future. Using the other sector's wage is probably a good convention in the wagesetting process, because it gives an indication as to the wage that can be successfully bargained for.

CONCLUSIONS

The main aim of this paper has been to identify the factors that govern the long run behavior of money wages in the manufacturing sector and the maquila industry in Mexico. This objective has been accomplished by using modern econometric techniques, with specific emphasis on the use of congruent and robust econometric models from statistical and theoretical viewpoints.

Our main empirical findings show that money wages are jointly determined in both industries, and that a relatively similar set of conditioning variables determines their dynamics. More particularly, it is found that money wages in both sectors depend on underemployment and on the specific conditions of the sector, the latter summarized by output growth in the manufacturing sector and by productivity growth in the maquila industry. This last fact reveals that insider workers have certain bargaining power in Mexico and that using the other sector's wage is probably a good convention in the wage-setting process, because it provides workers with an indication as to the wage that can be successfully bargained for.

Our results lead us to conclude that wage behaviour in those two industries in Mexico can be successfully explained by theories of wage determination that emphasize the institutional aspects of the labor market, and that take into account the dual or segmented structure of the this market in today's capitalism, in conjunction with some of the ideas proposed by Keynes in his General Theory.

REFERENCES

Bendesky, L., E. de la Garza, J. Melgoza and C. Salas, "La industria maquiladora de exportación en México: mitos, realidades y crisis", Estudios Sociológicos, vol. XXII, no. 65, May-August 2004. [ Links ]

Buitelaar, R. and R. Padilla, "Maquila, economic reform and corporate strategies", World Development, vol. 28(9), 2000, pp. 1627-1642. [ Links ]

Carrillo, J. and M. de la O, "Las dimensiones del trabajo en la industria maquiladora de exportación en México", in E. de la Garza and C. Salas (eds.), La situación del trabajo en México, Mexico, Plaza y Valdéz, 2003. [ Links ]

Dickey, D. and W Fuller, "Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root", Econometrica, no. 49, pp. 1057-1072, 1981. [ Links ]

Doeringer, P. and M. Piore, Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis, Lexington, Massachusetts, Heath and Company, 1971. [ Links ]

Doornik, J. and D. Hendry, Modelling Dynamic Systems Using PcGive 10, Timberlake Consultants Ltd., 2001. [ Links ]

Fairris, D. and E. Levine, "La disminución del poder sindical en México", El Trimestre Económico, vol. LXXI(4), no. 284, 2004, pp. 847-876. [ Links ]

Fujii, G. and C. Gaona, "El modelo maquilador como barrera de crecimiento del empleo y los salarios en México", Economía Informa, no. 323, February 2004. [ Links ]

González, L., "Mercados laborales y desigualdad salarial en México", El Trimestre Económico, vol. LXXII(1), no. 285, 2005, pp.133-178. [ Links ]

Herrera, F. and J. Melgoza, "Evolución reciente de la afiliación sindical y la regulación laboral", in E. de la Garza and C. Salas (eds.), La situación del trabajo en México, Mexico, Plaza y Valdéz, 2003. [ Links ]

Johansen, S., "Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors", Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, vol. 12, no. 2-3, 1988, pp. 231-254. [ Links ]

Keynes, J., "The collected writings of John Maynard Keynes", vol. VII, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, London, Macmillan, 1980. [ Links ]

López, J., "The macroeconomics of employment and wages in Mexico", Labour, vol. 13, no. 4, 1999, pp. 859-878. [ Links ]

Marshall, A., "Wage determination regimes and pay inequality: a comparative study of Latin American countries", International Review of Applied Economics, vol. 13(1), 1999, pp. 23-39. [ Links ]

Pagán, J. and J. Tijerina, "Increasing wage dispersion and the changes in relative employment and wages in Mexico's urban informal sector: 1987-1993", Applied Economics, vol. 32, no. 3, 2000, pp. 335-347. [ Links ]

Phillips, A.W, "The relation between unemployment and the rate of change of money wage rate in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957", Economica, New Series, vol. 25, no. 100, November 1958, pp. 283-299. [ Links ]

Phillips, P.C.B. and P. Perron, "Testing for unit roots in time series regression", Biometrika, no. 75, 1988, pp. 335-346. [ Links ]

Ramírez, M.D., "Desigualdad salarial y desplazamientos de la demanda calificada en México, 1993-1999", El Trimestre Económico, vol. LXXI(3), no. 283, 2004, pp. 625-680. [ Links ]

Salas, C. and E. Zepeda, "Empleo y salarios en el México contemporáneo", in E. de la Garza and C. Salas (eds.), La situación del trabajo en México, Mexico, Plaza y Valdéz, 2003. [ Links ]

Seccareccia, M., "Wages and labour markets", in J. King (ed.), The Elgar Companion to Post Keynesian Economics, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, 2003. [ Links ]

Spanos, A., Statistical Foundations of Econometric Modeling, Cambridge University Press, 1986. [ Links ]

----------, Probability Theory and Statistical Inference, Econometric Modeling with Observational Data, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999. [ Links ]

----------, Testing for a Unit Root in the Context of a Heterogenous Ar (1) Model, Processed, Virginia, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and Technical University, Department of Economics, 2000. [ Links ]

This article was benefited by Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT) IN301660-3, which is supported by Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA) at UNAM. The authors thank to two anonymous referees for helpful comments.

1 Attributing this view to Keynes is misleading because in The General Theory causality runs from demand to output and employment, and then to wages (and not the other way around). Indeed, after analyzing the effects of the fall in wages upon effective demand, Keynes concluded that even though higher employment required a lower real wage (given his assumption of decreasing marginal returns to labor), it is not rigid wages that produce unemployment (Keynes, 1980, p. 267).

2 The other countries considered in the study we cite were Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

3 Inflation was extremely high after 1982, having reached its peak m 1987 with an annual average rate of over 150 percent.

4 In 2000 the share of maquila exports on total exports was about 40 percent, and its share on manufacturing exports about 48 percent.

5 In 1980, about 88 percent of maquila workers had a job in firms located in the border area of the country; in 2000 that proportion had fallen to 58 percent (Carrillo and De la O, 2003).

6 Unless otherwise stated, in the paper and in our econometric work we use figures from National Institute of Statistics (INEGI).

7 See Salas and Zepeda, 2003, for details. Pagan and Tijerina (2000) carry out an econometric analysis to study the relationship between changes in relative formal/informal employment, wage levels, and wage inequality; but unfortunately their study does not extend beyond 1993.

8 The pressure of competition in the foreign and domestic market which began in the mid-eighties and forced modernization, most likely explains the faster rate of growth of labor productivity in manufacturing than in the maquila industry.

9 The increasing wage inequality in Mexico has been found to be strongly associated with worker's education level (Ramirez, 2004; Gonzalez, 2005).

10 See details about unemployment statistics in Lopez (1999).

11 As monthly series for underemployment do not exist before 1995, we constructed the missing data by simply interpolating the values on the basis of quarterly figures.

12 We also tried the open unemployment rate, which turned out to be insignificant in any of the estimated models.

13 We checked for misspecification with equation and system misspecification tests. All the statistical results and tests are available from the authors upon request. The econometric work was carried out with the help of PcGive 10.0 (See Doornik and Hendry, 2001).

14 It is worth mentioning that our models are robust to changes in variables. A valuable suggestion provided by an anonymous referee was to check the robustness of our estimates by changing the conditioning set. We have re-estimated many different versions of the models, including price levels, open unemployment rates and some other variables, and the main results about cointegrating vectors and other inferences remain the same. Such results are available upon request in txt or Word format.

15 In all the cases we estimated restricted VARS; thus not all the variables were actually modelled.

16 Of course there may be other possible alternative or complementary explanations. For example, H. Escaith (in private correspondence) has suggested to US that the overreaction of wages in the maquila sector may be due to a quicker reaction to changes in external competitiveness. An alternative to both hypotheses is that labor arrangements are more flexible in maquiladoras and labor force is more homogeneous. Average wages react therefore more rapidly in maquiladoras than in traditional manufactures, where labor arrangements are more inertial and where the composition of the working force is much more heterogeneous due to historical context. Unfortunately, it is impossible to discriminate among these alternative hypotheses with the data at hand.

17 The coefficient of variation of the maquila gross value of production is about 40 percent lower than the coefficient for the manufacturing industry.

18 Output does not appear as an argument in the wage equation for the maquila industry. In a wider analytical framework, this finding may perhaps be rationalized with the argument that the latter sector sells practically the whole of its production abroad, so that higher maquila wages do not stimulate demand for maquila goods.