JEL Classification:* E44, G21, G32

Introduction

In the last decade, the increasing presence of foreign banks in many emerging countries has heightened the debate on the factors that induce international banks to enter those markets; the net gains the host countries expect to attain with the opening of their financial markets; and the actual effects on those markets and economies from the entry of foreign banks.1

Traditionally, international banks’ entry was linked with their interest in being able to support the foreign operations of their domestic multinational clients. This however does not explain why, as the more recent experience shows, foreign branches should cover local customers, especially if not large. It has then been argued that the sheer overall size of international banks presents many scale and scope advantages that counterbalance the problems of operating in countries with different culture and language and competing with local banks’ superior market information and socio-political connections.

Recently, many emerging countries have relaxed previous barriers against the entry or the operational limits posed on foreign banks. These moves have been justified in many ways, ranging from the desire to increase the stability of the banking system to the need to recapitalize it, especially after having suffered serious bank crises.

The resulting increased foreign banks’ presence has focused the debate on its actual effects. The dominant interpretation in the economic literature associates many advantages to this presence: better technology and management, especially for evaluating and treating risks; wider asset diversification, hence better risk diversification; easier and more stable access to international funding; increased competition, with consequent gains for families and firms; higher and more stable credit growth; decreased probability of government intervention for general bail-outs; less corruption; and the support by the home parent bank especially in case of financial crisis.2

Recently, the more optimistic version of this position has attracted increasing criticism. In particular, foreign banks’ entry has not made it easier for small and medium sized firms to finance themselves (Clarke et al., 2002). Moreover, in many cases, and Argentina is one of these, the parent banks may legally or de facto not accept the obligations deriving from the bankruptcy or closure of their foreign branches and subsidiaries, partly because of the unwillingness of their home country’s central bank to operate as lender of last resort of the host country (Del Negro and Kay, 2002). The resulting localistic nature of foreign banks lessens rating differences with private domestic banks (Crystal et al., 2001), consequently taking away much of the funding costs advantage. Some have questioned the assumption that the presence of foreign banks increases competition or that competition is based on efficiency and risk management (Calderon and Casilda, 2001; Penido de Freitas and Magalhães Prates, 2000). Some, rather boldly questioning the established consensus, assert the positive role of well-managed public banks.3

The general impression from this literature is that cross-countries studies tend to produce overall results that are more favourable to the presence of foreign banks than studies focusing on the experience of a specific country. This is not counterintuitive. The institutions (particularly the financial ones) of emerging countries are particularly heterogeneous, which makes generalisations difficult. Moreover, often large cross-country studies cover time periods when substantial changes may have affected one or more countries. This is the case for Argentina, for which analyses that comprise years before and after 1991 (as in Claessens et al., 2001) are strongly affected by the changes in the regulatory regime and the general economic framework: the 1989-1990 hyperinflation extends its effects at least up to 1991-1992 when an extensive state reform and a currency board regime were introduced.

Our reference is then the Argentine experience from 1993 to 2000, looking at the effects of foreign banks’ tendency to dominate the host market. This dominance has its roots in the adoption of a xenophilous stance by the government, and appears as a probable outcome given the vertiginous increase in the share intermediated by those banks in many Latin American countries. The 1993-2000 period is particularly significant for the Argentine economy, as it was characterised by a macro-monetary stabilisation obtained with the help of the convertibility regime (a version of currency board with the peso pegged 1 to 1 to the US dollar). During these years, there was a complete financial opening, extensive privatisations (including the banking sector), a strong growth of bank intermediation, a substantial increase in the share intermediate by foreign banks and the creation of the Mercosur. These profound changes were unfortunately accompanied by several external shocks. In December 1994, the Argentine economy started to be affected by the Mexican crisis, the ‘tequila effect’, which was to have heavy negative real and financial repercussions. As a consequence, the regulation of the banking sector, already channelled in the path traced by the Basel Accord, was strengthened and a US model of banking supervision was apparently adopted. The Asian and Russian crises of 1997 and 1998 seemed at first to have few repercussions, but at the end of 1999 the Brazilian crisis (characterised by a heavy devaluation of the real) plunges the Argentine economic system in a recession, which becomes more and more profound in the following years. The recession exposes clearly the systemic weaknesses of the economy, in particular its scarce competitiveness and the strong increase of its foreign debt. Our study does not embrace the crisis started in 2001 that has de facto frozen the operations of the financial system.

The present work is mainly based on banks’ balance sheet data that have been reconstructed starting from the monthly information transmitted to the central bank (Banco Central de la República Argentina, BCRA), and following the methodology adopted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).4 As far as possible we have tried to overcome the limits inherent to the use of balance sheet data supplementing it with further information.5

In what follows we adopt the traditional Argentine distinction among the institutional categories of public national banks, public provincial and municipal banks, private domestic banks, cooperative banks, subsidiaries of foreign banks and branches of foreign banks.6 Where not otherwise specified, we do not include in the analysis the Banco Hipotecario, which was a public national bank up to its privatisation in 1988; besides not possessing the full attributes of a commercial bank, it presents two large balance sheet adjustments that, given its dimension, would distort the series. Furthermore, since the Caja Nacional de Ahorro y Seguros was privatised at the beginning of 1994 and the Banco de Inversión y Comercio Exterior (BICE) never acted as a commercial bank, we generally reduce the group of public national banks to the Banco de la Nación Argentina. The group of the provincial and municipal banks is dominated by the Banco de la Provincia de Buenos Aires. Therefore, while discussing the role of public banks we will often refer to these two institutions.

In section 2, we present a synthetic analysis of the evolution of Argentina’s economy and banking system. In the subsequent sections, we consider some of the aspects discussed by the above cited literature: the net external position, the financing of the private sector, the competition due to the presence of foreign banks and its supposed influence over efficiency and risk management. Section 7 discusses other features of the presence of foreign banks in Argentina. The last section is devoted to our conclusions.

The evolution of the argentine banking sector

After countless vicissitudes, at the beginning of the 1990s the Argentine banking sector regained almost ‘ordinary’ features following a series of reforms that interested the State and the whole of the financial system. As shown in Table 1, starting from 1993 the banks benefited from a satisfactory macroeconomic stability, particularly in its monetary components. Notable is the growth of bank intermediation.

Table 1: Macroeconomic indicators

*Time deposits from 30 to 59 days. Average annual values.

Sources: IMF, International Financial Statistics (IFS), Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo (INDEC), Banco Central de la Republica Argentina (BCRA).

By contrast, real interest rates do not show any tendency to fall, if anything to increase, which points to unsolved problems in both the banking sector and the economy in general.

Over all this period, the banking sector is affected by a strong structural trend that leads to a drastic reduction in the total number of banks but not of their branches (Table 2). Such scaling down is due only in small part to closures (only 24 banks from 1993 to 2000), being mainly the result of mergers and acquisitions. In the same period, 17 banks, mainly provincial ones, are being privatised.

Table 2: Number of Banks and branches

Year-end values. Includes Banco Hipotecario. Own calculations based on data from BCRA.

The Argentine banking system has for a long time been characterised by a non-marginal presence of foreign banks. Table 3 contains the set-up date of the foreign banks having the longest presence in the country.

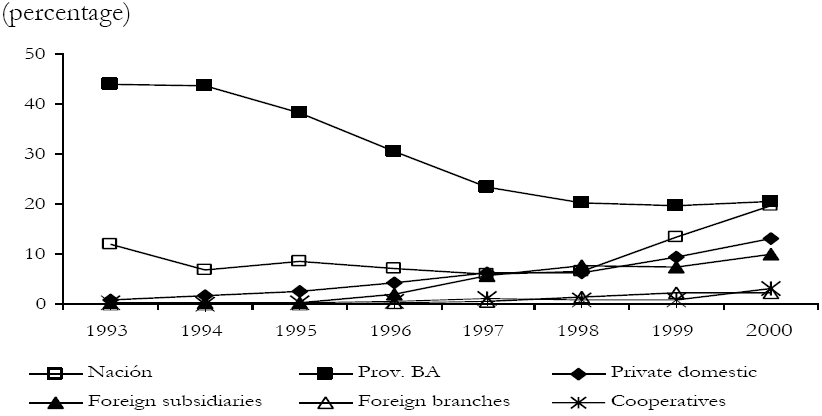

Therefore, the novelty of the 1990s is not the appearance of foreign banks, but the substantial increase of their weight in total intermediation, mainly resulting from their acquisition of the largest private domestic banks. Among the largest banks, only Banco Galicia remains under the control of domestic private capital, although with a substantial foreign participation. Other two characteristics of the 1990s are the bold entrance of the two largest Spanish banks (Banco Santander Central Hispano, SCH, and Banco Bilbao Vizcaya, BBVA), and the increasing attention paid to the retail market. Table 4 shows the evolution of the shares according to institutional groups. Note that the presence of foreign banks at the beginning of the period is far from being immaterial.

Table 4: Market shares

* Includes Banco Hipotecario up to 1998.

**Includes Banco Hipotecario starting from 1999.

Annual averages. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

The financial turmoil following the Mexican crisis of December 1994 accelerates existing trends, not least because encouraged by the supervisory authorities. They are the increase in the number and weight of foreign banks (mainly due to subsidiaries), several privatisations of provincial banks and the loss of market share by all classes of domestic banks.

The external position

Most of the literature cited in the introduction asserts that the presence of foreign banks benefits emerging markets in relaxing the international finance constraint and favouring the stability of international capital flows.

For Argentina, we must take care not to refer to absolute values of the external position given the increase in the period of the funds intermediated by foreign banks, due in large part to acquisitions of private domestic banks. In order to assess the propensity to net external funding we use a relative measure, the ratio between the percentage participation to the total net external position and the percentage share of total assets. When this ratio is higher than unity, the participation to the external position is above the system’s average. Table 5 shows that from 1993 to 2000 private domestic banks and foreign banks normally present values of the index higher than unity.

Table 5: Share of the net external position/share of total earning assets

*Includes Banco Hipotecario up to 1998.

** Includes Banco Hipotecario starting from 1999.

All over the period the net value is negative for all groups. Annual averages. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

Note the decreasing trend of the index for foreign banks, for both subsidiaries and branches. The fall in the index for private domestic banks between 1996 and 1997 is due to the migration from this group to that of foreign banks of seven banks, of which four of medium and large dimensions. In later years, this effect is mitigated in part by the privatisation of Banco Hipotecario. The value of the index for these seven banks and of their share on total assets is presented in Table 6.

Table 6: Seven banks migrated to the group of foreign banks in 1997

Annual averages. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

Figure 1 shows that during the most difficult period of the tequila effect (January-May 1995) private domestic banks did not fare differently from foreign subsidiaries, while foreign branches markedly lowered their exposure. The Banco Nación helped to support the financial system during the first impact of the crisis.

Month-end-values. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

Figure 1: Monthly evolution of the next external position

During the tequila effect foreign banks helped the financial system as much as domestic banks. However, more than domestic banks, foreign banks show in later years a clear tendency to decrease their exposure, as did also the seven banks after their migration to the foreign camp.

Loans and deposits

Given the small dimension of the Argentine capital market, the private sector is crucially dependent on banking loans. Figure 2 shows the evolution of the shares of loans to the private non-financial sector on total earning assets.

Annual averages. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

Figure 2: Loans to the non-financial private sector/total earning assets

Since over the period provincial and municipal banks suffered many crises, reorganisations and privatisations, we restrict our attention to the Banco de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, the dominant bank of the group. For public national banks we only consider the Banco Nación, which as we have already seen is the only one in this group with all the attributes of a commercial bank and by far the largest and with the best geographical coverage of the system.

Foreign banks show a negative trend in line with the rest of the system. It is evident for all bank groups a strong tendency towards homogeneous strategies. Also during the tequila effect foreign banks do not seem to behave differently from the rest.7 It is useful to examine more closely the behaviour of the different institutional groups during the tequila effect since, in contrast with other Argentine crises, this crisis comes from external causes in a context of general acceptance of the existing economic ‘model’.

The financial difficulties start in December 1994 and improve by June 1995, after a re-financing agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the re-election of Menem as President. As often happens in the first moments of a crisis, banks allow the private sector to substitute with bank credit the deficit in funds from other sources. The strong fall of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the first two quarters of 1995 (Table 7) is accompanied at first by an increase of bank loans to the private non-financial sector; in the following months bank credit shows more modest falls than GDP (Table 8).

Table 8: Loans to the non-financial private sector

Based on month-end values. Onw elaborations on data from BCRA.

The trend of the four largest domestic private banks8 is not much different from that of the subsidiaries of foreign banks, while the cooperative banks begin a drastic and lasting contraction. Notably, the branches of foreign banks behave as strong outliers (Table 8). This divergent behaviour is mainly related to the different pace in the loss of deposits, starting from December 1994 (Table 9).

Table 9: Deposits

Based on month-end values.

*Percentage change of the average for March-April 1995 over November 1994.

Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

In the period March-April 1995 the four largest private domestic banks show a loss of deposits (3.6%) similar to the one of foreign subsidiaries (4.3%).9 In contrast, the branches of foreign banks, and to a lesser extent the Banco de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, benefit from the flight to quality.10 The Banco Nación suffers during all the decade from the competition of the other largest banks, mainly due to the absence of a coherent strategy of public banking;11 during the worst part of the Mexican crisis it helps only occasionally in smoothing the downturn.

As shown in Table 10, private domestic banks are not able to offset the loss of deposits with other forms of funding, as can instead the other domestic banks. Foreign banks suffer from a consistent loss of this type of funding during the first months of the crisis.

Table 10: Costly liabilities net of deposits

Based on month-end values. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

In sum, only the branches of foreign banks are affected by the crisis differently from the two public banks and from the largest private domestic ones, mainly because they are the beneficiaries of a flight to quality. As can be seen dividing the data of Table 8 with those of Table 9, their assets are not, however, worked more to compensate.12 Moreover, two broader comments are suggested. First, the run was serious, but not dramatic. Second, without a pervasive presence of foreign banks, well-run public banks would have easily absorbed the flight to quality, as in part they did, while probably putting some brakes on the flow of funds abroad.

The financial problems caused by the Mexican crisis leave profound marks on the system: the share of loans to the non financial private sector goes on decreasing (Figure 2) and the composition of total assets uniformly shifts in favour of securities, mainly made up of public bonds (Table 11).13

Table 11: Loans to the non financial private sector/securities

Annual averages. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

The Banco Nación and the Banco de la Provincia de Buenos Aires seem to act as lenders of last resort, increasing their share of loans to the private sector in periods of systemic difficulties.14 In the period following the Mexican crisis, with the strengthening of the prudential requirements on capitalisation and liquidity of banks, the financing of the public non-financial sector shows a dynamics similar to the one already seen for public bonds (Figure 3). Overall we note a tendency to the homogenisation in the asset structure of the different typologies of banks; consequently, the distinction among institutional categories starts to lose its usefulness.

Annual averages. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

Figure 3: Loans to the non-financial public sector/costly liabilities

Finally, we may ask if the increasing role of foreign banks leads to the introduction or to the strengthening of some types of loan. This might be relevant for our discussion since the efficiency in the allocation of risks and funds is generally also related to the composition of loans. Classifying the loans to the private non-financial sector according to five categories (commercial, mortgage, with other collaterals, consumer, others), we may look for the existence and evolution of significant differences in the composition of loans among the institutional groups. The results of an Analysis of Varianza (ANOVA) analysis performed for the three main categories of loans are shown in Table 12.

Table 12: Differences in loans composition among institutional groups

Notes: 1 = public national; 2= public provincial and municipal; 3 = private domestic; 4S = foreign subsidiaries; 4B = foreign branches; 5 = cooperatives. The ANOVA is performed on the percentage composition of loans with a post hoc Tukey HSD test with p = 0.05.

The composition of loans follows the already mentioned tendency towards an increasing uniformity of strategies among the institutional groups. Moreover, foreign banks do not appear to exercise any significant pressure on the other banks. Individually, significant differences in loans composition remain only for the Banco Nación that goes on with a higher proportion of mortgages.15 We may thus conclude that the increasing presence and weight of foreign banks do not affect the allocative efficiency of the system as far as this depends on the typology of loans’ contracts.

Since data for loans composition show different currency compositions for the different typologies of loans, we also observe a strong relation between the loan composition and the currency composition of the loans portfolio. After the 1995 Mexican crisis the currency composition of the loans portfolio tends to converge to a lower proportion of contracts denominated in dollars. The Banco Nación is the exception mainly due to its larger exposure to mortgages.16 Since the majority of the contracts denominated in dollars concerns debtors with earnings in pesos, banks implicitly transform currency risks into non-covered credit risks.

In sum, when financing the economy, all banks, with the partial exception of the public ones, tend towards a higher homogeneity of operations and results, at levels that benefit less the economic system. As a reminder, similar results were found for the net foreign position. If we were to accept the hypothesis that a pervasive presence of foreign banks stimulates competition, at this stage of the analysis such competition seems to result in emulative, defensive strategies, which produce equilibrium that are increasingly less favourable for the Argentine economy.

Competition and profitability

Given the difficulties in directly measuring the degree of competition, most research focuses on the effects of competition, particularly on profitability and efficiency.

The heavy and prolonged reorganisation of the Argentinean banking system we discussed before lead to an increased concentration, especially visible in the medium and large dimension of banks (Table 13).

Table 13: Concentration indexes

Year-end values. The Rs refer to the shares of the first 3, 5 and 10 banks. HHI is the Herfindhal-Hirschman Index.

Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

Even if increasing during the period, the values of the indexes do not reach high levels by international standards. They reflect, however, the situation almost limited to the market in the Buenos Aires area, given that the Argentine banking system is polarised between the conditions of the Capital, where the wealth of the country is concentrated and most of the banks are located, and the periphery, which is much poorer, less financially developed and therefore less open to bank competition. The 50% increase of the Herfindhal-Hirschman index is, however, far from being immaterial.

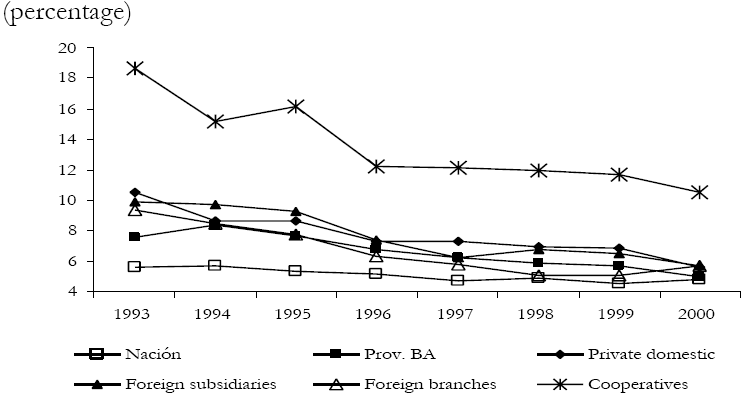

Let’s now consider profitability. For what seen just above, we can expect that the local banks (such as the cooperatives, the provincial and the municipalbanks) could enjoy higher margins. Table 14 presents the series for the interest margin.

Table 14: Interest margin (net interests/total assets)

Total assets as annual averages. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

The level of the margin is well above the OECD average but not substantially different from the Mexican one (Table 15).

Table 15: Interest margins for some OECD countries

Total assets as annual averages.

Source: OECD, Bank Profitability.

Brock and Rojas-Suarez (2000) confirm that high margins persisted in Latin America even after sweeping reforms that liberalised the financial markets. As we will see in the following paragraphs, Argentina shares with the rest of Latin America the causes singled out in that study: at a micro level, high operating costs, high provisioning and high liquidity requirements; at the macro level, high uncertainty. The decrease in interest margins and the increase in funds intermediated by foreign banks do not appear related since most of the margin decrease happens in the first part of the period (well before the substantial increase in foreign banks presence) and it concerns all types of banks. A more satisfactory explanation of the fall of interest margins is the gradual attainment of normal activity levels after the problematic 1980s (when the main bank operations consisted in the intermediation between depositors and the public sector) and 1989-1990 hyperinflation, and the perception of a decreased degree of risk of the private sector.

A careful analysis of the different types of banks reinforces the conclusion that the competition of foreign banks, which was potentially increasing after 1996 due to the acquisitions of large and medium sized domestic banks, was not focused on interest margins.

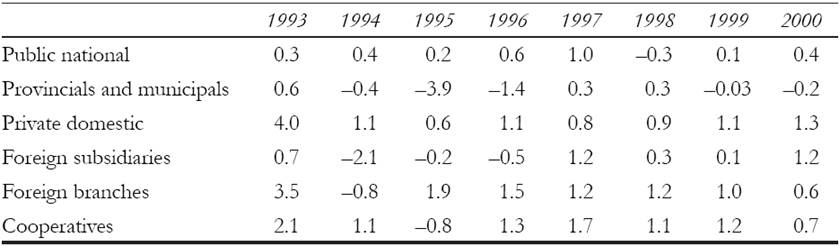

Tables 16 and 17 show the trend of Return on Assets (ROA) for the different institutional categories and for some OECD countries in the period 1993-2000.

Table 16: ROA (pre-tax profits/total assets)

Total assets as annual averages. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

Table 17: Roa for some OECD countries

Total assets as annual averages.

Source: OECD, Bank Profitability.

Note that the generally negative results for 1994-1995, in some cases lasting up to 1996, derive from the more severe regulations on risk management on top of the tequila effect. The following years see the continuation of the crisis for the provincial and municipal banks, the gradual weakening of the Banco Nación and the Banco de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, and generally better results for the private domestic banks compared with the foreign ones: an average of 0.99 against 0.82 with respective standard deviation of 0.21 and 0.32. These values must however be taken with caution since, on the one hand, foreign banks incur in substantial costs of acquisitions and reorganisation, and, on the other, the private sector gradually looses some of its best companies. The results in terms of ROA are in line with the international ones only for the private domestic and foreign banks.

Competition and efficiency

In Table 18 we show how, starting from a gross income much higher than the international average, the Argentine banks obtain a ROA more or less in line with those of the developed countries. We have taken as reference 1997-1998, as this was a period of good economic growth without significant problems for the Argentine financial system.

Table 18: Composition of ROA and efficiency, average 1997-1998

*Europe is the average of the European countries in Table 17.

IM is the interest margin; GI is the gross income; OC/TA are the operating costs/total assets; PR/TA are provisions/ total assets.

Own elaborations on data from BCRA and OECD.

Table 18 shows that, to obtain satisfactorily levels of ROA and global efficiency (last two columns), Argentine banks must start with a gross income that is almost the double of that for the US and three times that for Europe. This stems from the high operating costs and provisions common to all types of institutions operating in Argentina, apart from the cooperative banks.17

Claessens et al. (2000) assert that it is foreign banks’ entry by itself and not the growth of their share in intermediation that pushes up efficiency. Since the presence of foreign banks in Argentina dates well before the period here considered, our data show that those benefits did not materialise. As we will discuss in detail later, those improvements that are observable in the 1990s derive from the more favourable institutional and macroeconomic framework. This suggests that the levels of operating costs and provisions depend mainly on systemic features and that it is in this direction, not by increasing the presence of foreign banks, that the solution to the high margins should be sought.

Operating efficiency

If we adopt a narrow definition of efficiency, the first point to examine is whether the trends of operating cost are somehow linked to the competition stemming from the increasing presence of foreign banks.

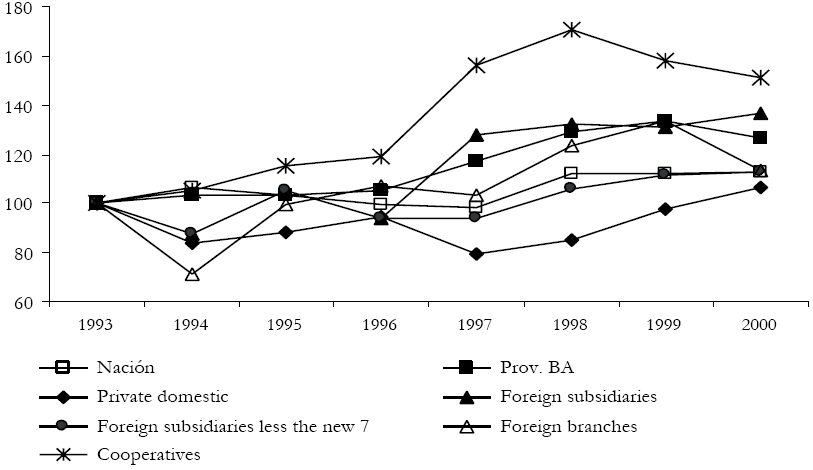

Figures 4 and 5 show that the increase in operating efficiency does not appear to be related to the bank typology but if anything to the initial level of operating costs and to the increase in intermediation characterising the period.

The correlations between the rates of change of the average bank size and of unit operating costs for the period 1994-2000 are computed in Table 19.

Table 19: Annual rates of change of unit operating costs and of the average bank size, 1994-2000

OC=operating costs; TA=total assets; NB=number of banks.

Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

The correlation coefficient computed for the average rates of change of the different groups is -0.54. The high correlation coefficients, especially those for the fastest growing average banks, indicate a relevant influence of dynamic economies of scale on operating costs. 18

All over the period, data on unit operating costs do not suggest the existence of significant static economies of scale, especially when we consider that the small dimension includes many wholesale banks. With reference to the first and to the last year of our period, Figures 6 and 7 show that X inefficiencies remain systematically dominant in the segment of small banks, with their reduction substantially depending on the disappearance of almost all cooperative banks. 19

The previous one is however a rather narrow interpretation of the concept of efficiency. In particular, if labour costs were positively related to the quality of human capital, we could hypothesise a direct relation between costs and value added. Table 20 shows the values for unit labour costs and gross income per employee.

Table 20: Unit labour costs and gross income per employee, average 1993-2000

Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

The relation between unit labour costs and gross income per employee across the different groups is substantial, with a positive correlation coefficient of 0.94. Note that foreign banks are the ones with highest unit labour costs and the highest gross income per employee. This situation characterise foreign banks since the start of the period. As shown in Figure 8, from 1993 to 2000 the trends of the different groups are not, however, substantially different.

Furthermore, the notable improvement of the foreign subsidiaries in 1996-1997 and the simultaneous worsening of the private domestic banks derives from the already discussed migration of seven banks from the private domestic group. Taking out the seven banks from the foreign series (foreign subsidiaries less the new 7) the dynamics of all groups appear similar, this time with the cooperatives that present a more marked improvement.

To conclude on our cost analysis, foreign banks do not show better results than the others. What seems to characterise them is the use of more expert manpower that permits to obtain a higher gross income per employee, suggesting a distinct focus of their operations. However, as we can see from Figure 9, the supposed higher labour quality does not produce a higher gross margin net of labour costs.20

The two public banks remain for all the period on levels that are dangerous for their survival, levels that should only be justified by taking very low risks.

Efficiency in risk management

For several reasons the data we can utilise in risk analysis are less reliable than the ones considered up to now. Starting from 1994, Argentine bank supervisors adopted very detailed, mechanical and even more stringent procedures for the evaluation of provisions and of the risk categories subject to different regulatory coverage. Table 21 shows the division in six risk categories and the required coverage.

Starting from 1994 risk provisioning reflects the increased stringency of supervisory requirements. Despite that, the debtors’ database monthly published by the BCRA in CD form shows non-occasional and non-marginal disparities in the risk evaluation of the same debtor made by different banks. Moreover, the provisions of the last years of our period, which as we have already seen are characterised by a substantial fall of GDP, do not increase in the measure we could have expected.

Tables 22 and 23 show two series of indicators of banks’ credit risks.

Table 22: Funds with irregularities 3-6/total funds

Annual averages. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

Table 23: Provisions/loans to the private non financial sector

Provisions do not include here adjustments from previous years. Stocks are annual averages.

Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

Private domestic banks and foreign ones constantly show the lowest levels of portfolio irregularities but among the highest percentages of provisions. Given the character of Argentina regulation, this partly reflects the interest rates policy adopted.21 The implicit interest rates for the loans to the non-financial sector seem to confirm this hypothesis (Table 24).22

Table 24: Implicit interest rates on loans to the non-financial sector

Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

However, the average interest rates on loans depend not only on debtors’ degree of risk (for which the share of loans to the public sector is relevant), but also on market power. For public banks the level of the average rates is strongly influenced by their exposure to the public sector, while for cooperatives banks, especially in the first years, it seems safe to assert that the market power is dominant.23 The above data suggest that the public and the cooperative banks assume the financing of the riskier part of total portfolio, with public banks that do not cover the higher risks with adequate mark-ups. Overall, and discounting the differences in operating conditions and on market positioning, the risk management by foreign and private domestic banks do not appear significantly different.

We can try to see if these conclusions may be confirmed by the evaluation of bank risk made by their creditors, that is, in the banks’ cost of funding. The literature is unanimous in finding a low market discipline exercised by depositors. For Argentina we can expect a higher sensitivity given its history of bank failures, and especially if we consider term deposits for less than 59 days. Figures 10 and 11 show the series computed for the implicit interest rates on deposits in pesos and in dollars.

While for deposits in pesos the advantage of public national banks is evident, for deposits in dollars the initial differences in favour of foreign banks tend to disappear in the following years. However, since deposits rates differ for different types of deposits, their composition determines the above result. The percentage composition of deposits (Table 25) and the implicit interest rates for deposit typology (Table 26) show that public banks are favoured by the larger share of current accounts.

Table 26: Implicit interest rates for deposit typology, 1998-2000

Onw elaborations on data from BCRA

Term deposits are the ones that most reflect explicit financial investment decisions, hence best reflect the market’s evaluation of bank risk. From the data in Table 26, available only for the last three years, we derive a net advantage for foreign banks, especially foreign branches, and for public banks. The more modest differences for the average interest on deposits depend therefore on the specific politics of deposit composition directed at minimising the cost of funding.

We can easily image that for domestic banks the high cost of funding may be related to country risk, which for Argentina never reached the investment grade; in principle the same should not be true for foreign banks, especially for foreign branches. We have however already argued that the localistic nature of foreign banks concurs to diminish the differences in the ratings of financial strength with obvious repercussions on cost of funding. For example, while in 1998-2000 the country risk spread for Argentina averaged 5 percentage points, the implicit interest rate on term deposits was 6.4% for Citibank, 6.8% for Banco Galicia (in 2000 the largest private domestic bank for total assets), and an average 8.8% for the seven smallest private domestic banks.

Considering together the results obtained for loans and deposits, we cannot assert that foreign banks adopted aggressive policies using their higher reputation and expertise to lower the cost of funding and loans’interest rates. There are on the contrary some indications that they exploited their access to international markets to select the best clients (cherry-picking) although not differentiating their internal interest policies from the rest of the system.24

We can now see how much risk management affects the profitability and fragility of Argentine banks.

Table 27 shows that the average share of gross income absorbed by provisions is not significantly different for foreign banks and private domestic banks. What it appears to differ is the policy of smoothing the effects of provisions on gross income, with foreign branches following more closely changes of GDP.

According to Figure 12, the amount of capital that insures risks not covered by reserves shows an increased dispersion in the tequila period, with a higher stability by foreign banks, tending afterwards towards homogeneous levels. Public banks appear increasingly undercapitalised and being able to elude the rigid regulatory capital requirements. 25

Annual averages. Own elaborations on data from BCRA.

Figure 12: Problem funds 2 to 6-reserves/capital

Table 28 shows the series for the minimum margin, computed as the value of the interest margin below which banks incur losses. High levels of unit non-interest net income and low values of unit operating costs and provisions lead to low values of the minimum margin. The lower is this margin, the more breathing space a bank has in case of a fall in interest margin. Given the complex interactions that the different operations induce in the items making up the income statement, this is a useful index of banks’ fragility.

Apart from cooperative banks, impaired by their high operating costs, the strengthening of supervision seems to push the other groups towards a higher homogeneity of the index. Non homogenous are however the operating conditions facing the groups, with the consequence that the differences between actual and minimum margins (Table 29) show the increasing weakness of public banks and the non brilliant situation of foreign banks.

Other features of the presence of foreign banks in Argentina

We may now supplement the previous quantitative analysis with the discussion of some more general topics, capable of further clarifying the experience of foreign banks in Argentina. We may ask whether their more pervasive presence helped banking regulation to be more effective; whether we may expect more favourable net effects for the future; and whether some of the problems that plagued the Argentine economy derived from the unconditional financial openness rather than from the increasing dominance by foreign banks.

It is useful to start evaluating the thesis put forward by Rojas-Suarez and Wiesbrod (Rojas-Suarez and Wiesbrod, 1996; Rojas-Suarez, 2002) according to whom a noticeable presence of foreign banks in emerging countries leads to a higher efficacy of the prudential regulatory regime. Many emerging countries are characterised by a high concentration of wealth, and by a relevant contiguity between real and financial wealth. In these conditions a regulation based on minimum capital requirements is not effective, the financial system is more fragile (since the domino effect is amplified) and during a general crisis it is very difficult to sustain bank capitalisation. Rojas-Suarez and Wiesbrod argue that the presence of foreign banks could sever this link, hence cancelling its negative effects. However, this requires strong and well-designed incentives that push foreign banks to recapitalise their local operations and not to use their dominant position in the local market to impose the logic of the too big to fail. This is a crucial passage for the validity of the Rojas-Suarez and Wiesbrod’s argument. Even if from what we have seen up to now this passage appears rather doubtful, a more detailed analysis of the general strategies of international banks and of their interest for a consistent presence in a market like the Argentine one may help to clarify the matter.

Looking at the conditions that in Argentina have contributed to lower the barriers against the entrance and the strengthening of international banks, it seems that bank crises have played an accompanying role, with a greater relevance assumed by the combination of high capital requirements, the favour granted by local authorities to their presence, and the propensity to sell by domestic owners attracted by a sort of ‘wealth effect’ deriving from the peso’s overvaluation (Kulfas et al., 2002, p. 111). For what concerns the strategies pushing international banks to enter into the financial markets of emerging countries, strategies affecting the results presented in the previous pages, it is perhaps sufficient to follow the general policies they have adopted with increasing determination during the 1990s. We refer particularly to their increasing estrangement from credit risk in favour of activities earning substantial, less costly and less risky fees and commissions.26 Worth mentioning is the role of many of these banks in the management of public debt and of the funds of residents, often at foreign branches of the same group. Another example is the management of pension funds, that foreign banks seems to consider one of the more promising sector in Latin America (Table 30). 27

Table 30: Market shares of pension fund administrators linked to the reported foreign banks*

* With controlling shares.

** On August 14, 2003, HSBC announced an agreement to acquire the 100% of capital of Afore Allianz Dresdner (3.3% of market share).

Source: AIOS, Asociación Internacional de Organismos de Regulación de Fondos de Pensiones.

Some foreign banks operated in Argentina as universal banks, acquiring directly, through the creation of financial holdings, or associating with multinational firms and local firms, the control of non financial firms, largely profiting from the favourable regime of foreign debt capitalisation accompanying the privatisation of publicly owned firms.28 With regard to activities external to their core business, these positions were subsequently dismissed, at least in part, generally in favour of foreign banks’ associates, sometimes also due to the necessity to return within the limits imposed by the home country bank regulation.29 Playing a relevant role in introducing multinational firms to the Argentine market, foreign banks also benefited by offering interesting opportunities of foreign investments to the liquidity thus created. There is no doubt that many foreign banks directly or indirectly facilitated the creation of privately owned foreign assets and, attracted by nice fees, favoured the strong dynamics of the foreign debt.30 However, also in this respect many private domestic banks did not pursue different strategies from foreign ones.

The strong interest of foreign banks for activities different from those of commercial banking is also confirmed in a cross section analysis by Dopico and Wilcox (2002), where a negative correlation is found between the share of foreign banking and restrictions put to their operations on the securities market and on the insurance and real estate sectors.

In the recent past, and probably even more in the future, it is a set of complex typologies of operations that attract international banks determining their entry into many financial markets, especially those of the emerging countries where the competition by domestic financial institutions is weaker.

We may expect that the new Basel Accord on bank capital requirements, which should come into effect at the end of 2006 and whose more risk-sensitive methodology will surely interest international banks, will strengthen the tendencies just mentioned, rendering less relevant the traditional activity of corporate lending. Given the relationship between finance and economic development, all this leads to reinforce for the future the doubts expressed in the present work on an eventual dominant role of international banks in the Argentine financial market.

Conclusions

The well established and increasing presence of foreign banks in the Argentine financial system does not seem to have produced that ample set of positive results expected by a large part of the economic literature. The evolution of the Argentine banking sector during the 1990s seems largely the result of macroeconomic factors and of the numerous reforms aimed at changing the economic and financial system radically. We may suppose that among the desired effects of these reforms there was a higher homogeneity among the strategies adopted by banks pertaining to different institutional groups.

Even the migration of the largest private domestic banks under foreign control has not produced, after several years, those increases in resiliency and efficiency expected by many analysts. Results similar to those here obtained for Argentina, hence different from those in most of the literature on emerging countries, are to be found for example in Brazil: absence of higher efficiency and profitability for foreign banks with respect to the domestic ones, and the absence of significant systemic improvements attributable to the increased presence of foreign banks (Carvalho, 2002; Guimarães, 2002).

The more recent crisis in Argentina, exploded at the end of 2001 to which a specific analysis should be devoted, seems to confirm the results here obtained for the previous period. Until the crisis erupted, foreign banks had a non secondary role in politically supporting the Convertibility regime, also when it had become well apparent the impossibility to manage the system without accumulating an unbearable public foreign debt, for which all banks had oiled the not always transparent mechanisms that produced an impressive net accumulation of privately owned foreign assets (Comisión Especial Investigativa sobre Fuga de Divisas, 2003). It was out of the question that at some point all this would have led to a breakdown. The way out from that regime was certainly chaotic, with a crescendo of public interventions badly devised and even worse implemented (asymmetric specification of banks’ deposits and loans, the freezing of deposits, the abrupt default on foreign debt, etc.). It was however equally clear the necessity of a prompt and radical exit from the Convertibility regime. If partly understandable, the hasty flight by Credit Agricole, the one a bit more composed by the Bank of Nova Scotia, the more recent exit of Lloyds Bank, Société Genérale and Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, the refusal to recapitalise by other parent companies and news about the disengagement of some foreign banks, among which ABN Amro and Citigroup, tend to confirm a secular pattern: in period of serious difficulties, foreign banks in Argentina do not adopt strategies different from the ones followed by domestic banks. There is no denying that any bank operating in Argentina has to face many difficulties and uncertainties deriving from severe weaknesses in the legal framework; however, foreign banks have been keen to exploit these when they could for their own benefit.

If we accept that the impoverishment of bio-diversity we have observed in the Argentine banking system might be detrimental for growth and development, it is open to doubts whether this is necessarily related to the increasing dominance by foreign banks. Our analysis did not find clear indications to support this hypothesis. If on the one side it was the favourable macroeconomic scenario of the 1990s and not the increasing presence of foreign banks to produce the better results we can observe, on the other side private domestic banks did not adopt different strategies; furthermore, there are no signs that they could have not done so in the absence of foreign banks pressure. In other words, the impoverishment of bio-diversity in Argentine banking could have led to similar results if the role played by foreign banks would have been taken on by private domestic banks.

The problem mainly rests on the system of incentives produced by the Convertibility regime and by the actions taken by the Regulatory Authorities. First, with an unrestricted financial opening we may not really expect private domestic banks pursue different strategies from that of foreign banks.31 Second, the diminishing attention paid by Argentine banks, both domestic and foreign, to the financing of the economy appears to be strongly influenced by the Argentine regulatory regime, with its dislike of local and small banks and with its rather punitive capital requirements for the financing of the private non-financial sector. Third, the authorities were restrained from pursing a complete privatisation of public banks only by political reasons. No serious thought was ever given to the approach, albeit debatable, allowing only a residual but functional role for public banks in emerging countries. When incapable of privatising them, the authorities’ action was in fact in the direction of not opposing, if not producing, the weakening of public banks.32

From this point of view, foreign banks appear as a willing instrument of a policy that has finally deprived the Argentina’s economy of the heterogeneity of strategies that would have dampened the negative effects deriving from the exposure of private domestic banks to the incentives coming from the international context.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)