The naïve greatly opened Julio’s world…Arte popular is of significant importance to Mexico’s visual art…You scratch and they connect. Simply stated, it opened the door for him to invent things.

Guillermo Sepúlveda, 20141

Mexican artist Julio Galán (b. 1958 Múzquiz, Coahuila-d. 2006 Monterrey, Nuevo León) was interested, at times, in how he could harness, integrate and transform in his painting, and in a smaller, lesser-known production of ceramic sculpture, typologies of the national, of mexicanidad (Mexicanness). Among his diverse sources of inspiration, Galán drew from Mexican arte popular (folk art and craft), which he juxtaposed with a myriad of everyday mass-produced objects and rare collectibles. While contracorriente (Countercurrent) artists in the immediate post-Revolution (María Izquierdo, Frida Kahlo, and Rufino Tamayo, among others) turned to regional material culture, drawing freely from pre-Columbian sources, Colonial and nineteenth Century portraiture, and arte popular for example, as means of formal and thematic innovation in Mexican art, Galán, a half-century later, excelled at post-modern collage, looking at some of the same objects and past cultural and artistic expressions as these Mexican vanguard artists, but through the lens of artifice; layering fragments from a variety of textual and visual sources, Galán reoriented the language of lo popular (of the masses) as gender-expansive and culturally inclusive.2 Within the new figuration in Mexican painting of the 1980s, known as neomexicanidad (neo-Mexicanism), Galán did not invoke national heroes of the Revolution, defining historic events such as the Conquest, or references to the pre-Columbian Era as some of his con- temporaries did (Javier de la Garza, Dulce María Nuñez, Germán Venegas), but rather, he chose self-representation as means to address the performance and construction of gendered identity.

Performance Studies scholar Diana Taylor explains that, “Performance […] indicates artificiality, simulation or ‘staging,’ the antithesis of the ‘real’ or ‘true.’”3 In 2014, I wrote to Taylor looking for confirmation that I could consider Galán’s painting through the lens of performativity, as I do artists who challenge stereotype to reveal complex identity through their performance and cultural criticism, such as Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Coco Fusco, Astrid Hadad and Jesusa Rodríguez, subjects of Taylor’s scholarship. She affirmed, “Yes, Julio Galán seems to be staging performances in his art.”4 Taylor ex- amines the slipperiness in defining the terms performance, performative, and performativity in her essay on “Still Performance” in relation to Gómez-Peña’s work. I use “performative” in reference to Galán’s art and persona, as an adjective of performance, as well as taking into consideration Galán’s interest in artifice and the performance of gender. Galán follows Judith Butler’s “recognition of the performativity of everyday life and to break with the gender script through performing gender roles in new (and often parodic, and often humorous) ways.”5 Curator Magali Arriola adds that the performative aspect of Galán’s painting he expressed in his treatment of the canvas as theatre with stage scenery, curtains, and carnival props, but clarifies, “and yet, I would not go so far as to call all of these games that he played of self-representation a ‘performative work.’ It falls just short of that, but the intention was always very present.”6 I argue here that integral to Galán’s performative approach as he develops his ideas about identity through his art, is how he engages with, activates, and transforms lo popular.

This aspect of Galán’s work is much more intricate and weighted than the facile relationship that scholars and critics of his art have repeatedly drawn between the artist and his predecessor Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) as one of a shared debt to the ex-voto and retablo (in addition to Galán and Kahlo’s com- mitment to the self-portrait and the autobiographical).7 Galán built a robust resume over the course of his career with dominant critics of contemporary art contributing essays to his numerous international exhibition catalogues, and journal, magazine, and newspaper articles. They considered Galán’s artwork from diverse points of view-psychoanalytical, mythological, and philosophical, for example, classifying Galán’s art under a wide rubric as naif, magical realist, surrealist, metaphysical, neo-expressionist, neofrido (aligned with Frida Kahlo), “gay art,” neo-Baroque, and neo-Mexicanist. Presented here is an analysis of Galán’s post-modern translation of specific source material that he had access to-a focus heretofore absent from the above writings. I propose that Galán’s artistic process as he engaged with lo popular can, in part, be understood in light of Susan Sontag’s close inspection and definition of Camp, Francisco de la Maza’s considerations of lo cursi, and Gerardo Mosquera’s assessment of post-modernism’s Kitsch.8

Typologies

Inculcation into and performance of the gendered language of types can begin at a young age in Mexico. A family photograph of Galán (Fig. 1) approximately at age six, captures him in elaborate charro costume, that of the “virile horseman,” as art historian Lynda Klich explains, who from representing the Spanish creole elite became, in the immediate post-Revolution, the “heroic symbol of mexicanidad,” the embodiment of the masculine national character, while at Galán’s side stands his younger cousin Golondrina dressed as a china poblana, characterizing the “ideal national femininity.”9 Together the charro and china poblana perform the national dance, the Jarabe tapatío, or Mexican Hat Dance.

1. Julio Galán with his cousin Velia (Golondrina) Dávila Romo in Múzquiz, Coahuila, ca. 1964, dimensions unknown. Photograph: unattributed. Courtesy of and reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

The two were participating in a September 16th Mexican Independence Day annual celebration hosted at their elementary school in Múzquiz.10 Later Galán would turn the language of types on its head, incorporating with purpose signs of mexicanidad, Mexican cultural nationalism, at times in his artwork, generally to queer, break and reshape fixed or institutionalized notions of Mexicanness.11 In the wide canvas Mientras el cielo ríe, la tierra llora (While the Sky Laughs, the Earth Cries) of 1986, for example, a rigid figure bearing a guitar is costumed in an expansive, ornate dress and posed off-center, stiff as a cut-out doll against a stage backdrop of a mountainscape with song lyrics (those of the painting’s title) running across the top of the canvas. The combination evokes the nostalgia of 1930s-50s Mexican Golden Age of Cinema musicals, which featured archetypes of the national played by such celebrities as María Félix, Dolores del Río, and Jorge Negrete, often singing canciones rancheras or boleros; these songs from the countryside were about unrequited love, aban- donment by a lover, or betrayal. For example, the comedia ranchera film Bajo el cielo de México (Beneath the Mexican Sky) of 1937, which romanticized rural life on the hacienda, was advertised by Azteca Films with a poster featuring the gamut of stiff national Europeanized archetypes-the china poblana and charro dancing the Jarabe tapatío, a second guitar-playing charro, and a Tehuana, all under a starry sky, characters which Galán treated in the late 1980s with a Camp sensibility.

Here Galán steps into the entertainer’s red shoes as his doppelganger confronts us with garish eyeshadow and heavy lipstick. On his small feet are Mary Jane flats, while pink nail polish dons the tips of his fingers. The artist’s long wavy hair fans out like his flared skirt. Bobbles hang from his ears and shiny sequins decorate the ruffles of his festive dress. Galán’s impassive, direct gaze lends his performative Camp an unlikely serious demeanor; his trans-act laughs in the face at any attempt at sober patriotism.

Where do the canvas’ lyrics derive from? Everardo Salinas Peña, Galán’s former assistant from that time, commented that the song was likely instru- mental and he offered several interesting possibilities for their source: Bra- zilian Tropicalismo singer Caetano Veloso, jazz-rock fusion guitarist Carlos Santana, or trumpeter Herp Alpert. Asking Salinas Peña if Santana’s “Earth’s Cry, Heaven’s Smile” of 1976 might be the one while remarking to him that I found the song rather chafa (sappy), he replied, “If you only knew how very cursi-Kitsch Julio was.”12 A disparaging term, cursi refers to something of questionable taste, pretentious, affected, trying to be refined. Susan Sontag’s treatise on Camp maps where the cursi-Kitsch-Camp enters Galán’s art.

Notes on “Camp”

Sontag’s in-depth essay “Notes on ‘Camp’” of 1964, an extensive analysis of the Camp sensibility, predicts Galán’s approach to culture, his artwork (and apparently life), to a T (an idiom Galán, as a trained architect, might have appreciated).13 Her essay is of such relevance to the artist that extracting specific points in the order that she presents them, her numbered “notes” (from 1-58), proves useful. She begins by telling her readers that “the essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.”14 The artificial is what Galán consistently emphasizes both thematically and in his treatment of the surface of the canvas as he mars it in a number of ways (such as cutting, graffitiing, cancelling). Sontag indicates that Camp is a “private code, a badge of identity, even among small urban cliques,” which initially, is Galán’s Monterrey audience, those industrial elite whose eclectic cultural tastes cross the Border to the North (Dallas in particular) and beyond.15 Camp attracts and repels, Sontag explains, and “converts the serious into the frivolous”-love and official nationalism are Galán’s targets.16

Sontag describes Camp as a “mode of aestheticism” whose “way” is not one of beauty, but in terms of the “degree of artifice, of stylization.”17 She reiterates that stylistically, Camp’s world vision is the “love of the exaggerated.”18 Galán points to artifice through exaggeration in scale, anguished emotion, baroque, dense compositions, and stylization in his cartoon-like, flat, unmodulated figure during much of his artistic production, repetition of his androgynous adolescent self-portrait, collage and montage additions to the canvas surface, and his conveyance of the tragic. Galán pretends neutrality (detachment, apo- litical attitude) with regard to content, a requirement for Camp sensibility according to Sontag, by consistently omitting or hiding parts of the narrative puzzle. By employing this strategy Galán veils his content, avoiding any direct or overt statement, assuring the dialogical nature of his imagery, requiring the viewer to fill in the blank. Sontag’s note #5 describes Galán’s painting well: “Camp art is often decorative art, emphasizing texture, sensuous surface, and style at the expense of content.”19 She goes on to explain that Camp is marginal; marginality and difference drive Galán’s art. Collapsing Kitsch into Camp, she notes that Kitsch and bad art can be Camp. Camp is urban, but serene, naïve and pastoral says Sontag-all elements that Galán holds closely.

That Camp “sees everything in quotation marks” aligns with Galán’s interest in role-playing, anthropomorphism, and gender construction.20 He points to the pseudo, mythologized aspect of what something is supposed to be, or pretends to be, in terms of social, cultural, or gendered expectations. Camp is the “metaphor of life as theatre.”21 Galán appeared to live his life performatively, while proclaiming that he did not wear disguises, that disguise was his natural expression. For example, when asked if he considered his manner of dressing to be art, he stated: “I do not see it that way; it is not intentional. That is how it turned out and that is the way I am […] they say it’s a disguise, but it is not to me. I do it because […] I am restless.”22 While extreme sentimentality is Camp’s vision of the past, which is also Galán’s, his is also tinged with pain, trauma, and anger, even though Sontag states that there is never tragedy in Camp; Galán’s expression of tragedy in his art is theatrical.

Camp both discloses and corrupts innocence, says Sontag. Again, as if ad- dressing Galán, Sontag claims that successful Camp -Camp that cannot be taken seriously, one backed by risk and glamour-, has “the proper mixture of the exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naïve,”23 while extravagance is its hallmark. Invoking the old-fashioned, as Galán does through, for example, his mixed-media collage of old wallpaper on his canvases, creates the detachment or sympathy necessary for Camp.

The playfulness important to camp is evident in Galán’s artwork in his endless games of wordplay and puzzles. Sontag nails Galán’s point of view when she proclaims “Camp-Dandyism in the age of mass culture-makes no distinction between the unique object and the mass-produced object,”24 this describing Galán’s commitment to juxtaposing high and low in his en- vironment and art. While Camp is democratic, states Sontag, Camp taste belongs to the affluent. Born into the upper, if provincial class in Múzquiz, Coahuila, and transported as a 10-year-old into the upper ranks of the close-knit Monterrey elite of Nuevo León, Galán chose the profession of being an artist, one under-valued by his parents. From his privileged position, Galán could collapse and juxtapose signs of social and racial class hierarchies, while expressing Camp’s love for human nature. Sontag names homosexuals as constituting the vanguard, the most articulate audience, and inventors of Camp. Given her observation that the “androgyne is certainly one of the great images of Camp sensibility,” Galán’s basis in Camp is confirmed.25

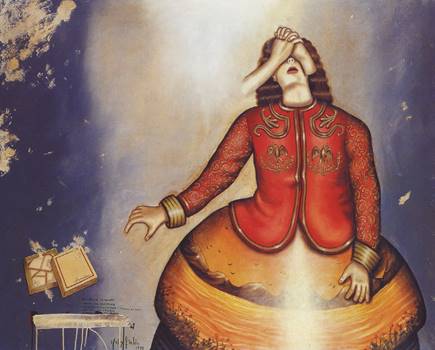

Take Niña triste porque no se quiere ir de México (Sad Girl because She Does Not Want to Leave Mexico) (Fig. 2) of 1988, for example, where Galán employs the language of Camp sentimentality, detachment, and theatricality. Center stage and in the spotlight, the protagonist bears the weight of the national, costumed in a jacket embroidered with the Mexican coat of arms-the eagle having captured a snake in its beak stands on a bed of nopal cacti; this insignia on the Mexican flag points back to the founding myth of Tenochtitlan (Mexico City). The figure’s gourd-like, voluminous skirt is a golden-hued vista of mountains, birds, and sea; hardly a garment made of fabric, the skirt recalls an arte popular vessel with its curved, hard, painted surface, the idealized landscape a Kitsch painting within a painting.

2. Julio Galán, Niña triste porque no se quiere ir de México (Sad Girl Because She Does Not Want to Leave Mexico), 1988, oil on canvas, 160 × 180 cm. Photograph: unattributed. Reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

The “sad girl” is clothed in the nostalgic imagery of national territory. Immobile, the figure gestures affectedly towards a handkerchief just out of reach. Galán has scumbled the canvas surface calling attention to its artifice. Additionally, he has drawn a loaded, dripping brush across part of his text, to create a large cancellation mark erasing a piece of this puzzle. From an ethereal, limbatic space emerge disembodied, clasped hands whose fingers interlace in both a prayerful and violent gesture to cover the subject’s eyes. Deprived of outer vision and with lips parted, the subject appears in a state of reverie. Song lyrics or a poem bemoan the forlorn and melancholic: “Algún día volveré a ti; siempre ten presente; que en esta pinche vida estamos de paso; no estés triste” (Someday I will come back to you; always remember; that in this wretched life we are passersby; so don’t be sad).” With little relief on the horizon, Galán dates the canvas forward in time by a decade, to 1998. Camp’s appeal is an enduring one for the artist.

Notes on lo cursi26

The Mexican art historian Francisco de la Maza in his essay “Notas sobre lo cursi”27 defines the term as “the desire to arrive at the heights of elegance and what is distinguished, and only make it half-way, but, of course, believing that one has arrived,” sincerity being a requirement for lo cursi. Or, even more succinctly, he applauds the writer Antonio Gómez Robledo’s two-word defini- tion of lo cursi as “failed exquisiteness.” One could accuse Galán of taking just such an approach in his obsessive painting of the lace embroidery covering the oversized (and phallic) bed in Roma of 1990. Examples of lo cursi for De la Maza include sappy rhyming love verses on a Mother’s Day card, doves, cherubs, post cards, porcelain figurines of dancers or musicians, stamps of saints, all toys that reduce everyday objects to miniatures; and then there is the imagery of devotional cursilería including costumes for First Communions, wedding cakes, and Baby Jesuses. De la Maza’s description matches objects Galán collected and incorporated on his canvases.

Every person’s dream of something unattainable-be it king or millionaire-is cursi says De la Maza. It is domestic imagery, cheap and commercial, not a work of art, that is cursi, the author points out (unless of course, you are Julio Galán producing the art nourished by the world of cursilería). Cursilería ejemplar, confirms De la Maza is Mexico’s commercial chromolithograph calendar, or “cursilería calendárica,” a “cascade of sweetening scenes of the greatest of bad taste.”28 These popular, brightly colored, illustrated calendars, which were widely produced and distributed in Mexico from the 1930s to the 1970s, served as a form of modern publicity promoting brands and products, while selling visions of an idealized and utopian Mexico with romanticized ideals of landscape, masculinity, and femininity.29 Famed chromolithograph artist Jesús de la Helguera’s (1910-1971) sensual 1940 interpretation of the myth of the Legend of the Volcanoes, a Romeo and Juliet-type love story of racial mestizaje or miscegenation, merges woman with nature, her sleeping figure supported by volcanic rock, the curves of her scantily-clad body echoing those of the distant Iztaccíhuatl mountain, while her pining Indian lover’s rounded, muscular back mirrors Popocatépetl’s majestic form.

In El amor contigo nunca entró en mis planes (Love with You Never Was Part of My Plans) (Fig. 3), of 1991, Galán employs the language of lo popular appropriating the cursi-Kitsch calendar landscape, common to calendario imagery, his mountains as reminiscent of Monterrey’s Cerro de la Silla, as of the Valley of Mexico. The picturesque landscape was an important element in Galán’s oeuvre, one he often achieved by collecting and altering found paintings. Upending the hyper-heteronormative Legend of the Volcanoes imagery, here Galán secures to his picture-perfect, still, and saturated canvas, two pistols in a showdown standing in for a fatal, phallic love affair. White paint drips from the end of one barrel, an allegory, perhaps, for spent semen. Across the purple skies appears the painting’s title in capital letters, a statement of the unexpected, the uncontrolled, of fate-perhaps, ill fate.

3. Julio Galán, El amor contigo nunca entró en mis planes (Love with You Never Was Part of My Plans), 1991, oil on canvas with montage, 2 × 2.5 m. Photograph: Unattributed. Courtesy of the Galería de Arte Actual de Monterrey. Reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

The mythology of the national imagined by artists such as Helguera as they worked for calendar factories like Galas de México, further included adopting the tradition of the nineteenth-century romantic costumbrismo in art where European artists, Claudio Linati, Eduard Pingret, and Carl Nebel, among others traveling through Mexico, focused on local landscape, labor, and costumes to depict exoticized typologies of the national for foreign consumption; they did so producing “high” art-paintings and lithographs, then reproduced and distributed in published volumes. Following their lead, local artists such as Agustín Arrieta in Puebla internalized the foreigner’s gaze, contributing to genre painting with his more individualized and intimately narrative portraits of types as in his well-known ca. 1850s El chinaco y la china.

While Mexican in character, the mechanically and mass-produced “low” art cromos were ironically filled with creoles or Europeans with blue eyes, but dressed as charros, chinas poblanas, peasants, and workers, states De la Maza. “For lo cursi, what is attractive or considered human beauty is always white, blonde or brunette, generally rosy, of fine and serene factions, of tender ex- pression.”30 He appends his essay with a comparison of Camp and cursi in a scathing critique of a discussion of Camp by Carlos Fuentes, Carlos Monsiváis, and Guillermo Piazza in the journal Siempre on March 30, 1966, concluding that their analysis of Camp colonizes and cannibalizes lo cursi-they are one and the same, De la Maza argues.

An extreme example of such an expression is Galán’s contemporary, the internationally-known Mexican artist and musician, Astrid Hadad (b. 1947). Since the early 1980s Hadad has performed on nightclub stages in Mexico City such as La Cueva and La Bodega, where she wields social criticism, attacking patriarchal systems in particular, through cabaret. Costumed in her zany, campy-cursi signature wearable art, Hadad blends popular songs and ranchero, rumba, son, merengue, salsa, and bolero music, and political satire with highly theatrical precision to create a genre of music she calls “Heavy Nopal.” As Rosalyn Constantino points out, Hadad “performs both the continuity of stereotypical roles and a critical analysis of them” (such as La Llorona, the long-suffering woman), adding that Hadad “structures her performance around issues of gender bias, political authoritarianism, religious dogmatism, and feudalistic systems whose hierarchies are based on ethnic groups and class distinctions in general, and on female submission and male machismo in particular.”31 Hadad embodies the camp-cursi sensibility in her multimedia performances with her outrageous costumes highlighting lo popular, and her raucous music as she parodies national and religious iconography while targeting abuses of a patriarchal system through her theatrics and lyrics on stage. Galán’s approach is highly sympathetic to that of Hadad, treating such imagery through painting and still performance.32

Galán explains of his 1987 solo exhibition at the Museo de Monterrey in preliminary conversations with the museum’s director Javier Martínez, “It was not to be a retrospective exhibition, but rather, I was to create a group of artworks especially for the occasion, and what was most important was that I could do it with complete freedom.”33 He recalls having painted 16 large canvases, some with “folkloric themes;”34 these Lowery S. Sims, then-Associate Curator of Twentieth-Century art at the Metropolitan Museum, refers to in her essay for the exhibition catalogue as “a unique synthesis of Mexican cultural manifestations,”35 while emphasizing his international, rather than regional positioning, stating that other of Galán’s canvases in the exhibition “step out of the specificity of Galán’s ‘mexicanidad’ and […] betray his involvement in the so-called Lower East Side zone of art activity in New York […] and participate in an imagery that is more directly related to the art historical gymnastics of the new figurative art of the United States.”36

Having resided in New York City part-time since 1984, Galán recognizes having embedded some of his production for the exhibition with a certain nostalgia (not commenting on, or admitting to any visible acerbic intent) addressing Mexican identity in his artwork only after gaining distance from his family and country.37 Galán’s campiness moves fluidly into the arena of Kitsch.

Notes on Kitsch

Galán expresses that nostalgic sentimentality by infusing certain of his canvases with irony, ridicule, and a tourist-Kitsch approach. While drawing for source material from such low-brow imagery as the aforementioned cursi chromolithograph calendar art, which features idealized landscapes, and the hypermasculine and hyperfeminine language of the national, Galán effeminizes his types while producing imposing, aesthetically appealing fine art-one far from heteronormative in visual language. Using Gillo Dorfles’ definition of Kitsch as “the application of bad taste to art,” art historian Ida Rodríguez Prampolini names five of Galán’s Mexicanist canvases in which “the presence of Kitsch sought by the artist is obvious,” not elaborating on what those ‘obvious’ aspects of bad taste might be.38 However, she states that Galán is aware that, if there were a Kitsch country, Mexico would be it. She identifies Galán’s version of Kitsch present in his mexicanista paintings as one of “sarcastically deriding true Kitsch,” which she defines as an unconscious, natural product of the common man; omitted from her essay is any discussion of the relationship between Kitsch and lo cursi.39 The artworks Prampolini refers to embody the self-deprecation, snobbery, play- fulness, and Camp that Galán directs at his Monterrey audience; his imagery mocks social and cultural elitism while invoking the theatre of the national.

As Robert Solomon puts forth, Kitsch:

Is art (whether or not it is good art) that is deliberately designed to move us, by presenting a well-selected and perhaps much-edited version of some particularly and predictably moving aspect of our shared experience, including, plausibly enough, innocent scenes of small children and our favorite pets (when they appear in his artwork, Galán’s cute animals are always accompanied by an edge of danger) playing and religious and other sacred icons.

In his treatment and embodiment of religious imagery,40 Galán depended on a shared experience and sympathy in his audience’s visual reading of his art- work. “Excessiveness, role-playing, and overt decoration”41 describes Galan’s version of Kitsch. Typically, that which Kitsch is considered “in poor taste because of excessive garishness or sentimentality, but sometimes appreciated in an ironic or knowing way.”42 Gerardo Mosquera, in his essay “Bad Taste in Good Form,” adds that Kitsch, defined by its inferior form and poor quality, is one of the “raw materials” that postmodernism’s avant-garde in- corporates into their “high” art, as they recycle “degraded and obsolete” low status forms; these forms can be considered “anti-artistic” or “pseudo-art.”43 Such would be considered Galán’s strategies of incorporating objects and imagery into his canvases to include mass produced stickers, tulle and satin fabric, artificial flowers, pompoms, plastic fruit, wallpaper, ornaments, calendar imagery both religious and secular, and more.

Galán’s direct reference to Mexican iconography was not constant in his work. Within his oeuvre he created perhaps ten paintings, widely exhibited since their production in the late 1980s, in which he exploited the visual language of official nationalism and the popular masses.44 And several of these he painted with a specific goal in mind, to include them in the above-mentioned major solo exhibition held at the Museo de Monterrey in 1987 that later traveled to Mexico City’s Museo de Arte Moderno. While Galán’s treatment of the language of types would likely have been read as intentionally cursi by national audiences, the presentation of his Mexicanist paintings outside of Mexico in exhibitions such as Aspects of Contemporary Painting (1990) in New York City and Les Magiciens de la Terre (1989) in Paris, the latter which claimed to be the first worldwide exhibition of art (by “magicians,” rather than artists), fell under the overarching discourse of exoticism.45

Reorienting the China poblana, the charro, and the Tehuana

In 1992, the Monterrey daily El Norte published a special supplement about the Museo de Monterrey on the occasion of the museum’s fifteenth Anniversary. Included were Galán’s recollections of the 1987 exhibition, where he spoke of “three paintings inspired by the Mexican popular fairs, that contributed in creating a particular ambience. One was of a Tehuana, another of a China poblana, and one more, of a charro with his horse. In one of them was a live model, who was an element integrated into the exhibition.”46

In his canvas Tehuana en el Istmo de Tehuantepec and China poblana (figs. 4-5) Galán cut a hole where the face belonged on the figures so that not only he, but anyone, regardless of class, race, or gender, might assume their identity.47 For the exhibition’s inauguration he had a false wall built behind the China poblana directing his twin friends Lorena and Claudia Lozano to alternate posing with their faces in the canvas hole occasionally making muecas (silly faces), moving their eyes and sticking out their tongue at approaching Museum-goers.48

4. Julio Galán, Tehuana en el Istmo de Tehuantepec (Tehuana in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec), 1987, oil/acrylic/montage on canvas, 2.08 × 2.08 m. Photograph: Unattributed. Courtesy of the Collection of Diane and Bruce Halle. Reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

5. Julio Galán, China poblana, 1987, oil on canvas, 1.9 × 1.2 m. Photograph: Camilo Garza y Garza. Reproduced with permission of the Galán Family. Julio Galán (left) and Cristal Martínez (behind artwork).

A body fills the canvas, clothed in the traditional dress of the china poblana (embroidered short-sleeve white cotton blouse, full skirt decorated with sequins and beads, and rebozo shawl that wraps around the waist, threads over each shoulder as straps that then tuck into the waistband and hang down); her strawberry-red skirt topped with its green silk band billows out like an engorged, ripe fruit. The empty, cut-out hole where the face should be is framed by braided hair tied off with enormous bows. She holds a bouquet of roses in one hand, more typically a trait of the Virgin of Guadalupe; perhaps Galán was familiar with Mexican poet Amado Nervo’s 1938 “Guadalupe La Chinaca,” where he conflated the two icons as chaste, proper, and adorned in the colors of the Mexican flag. Sign-like, “china poblana” is lettered over a swatch of delicate landscape at the top of the canvas, below which on the right-hand side the artist painted the Chinese characters Zhongguo, meaning the country of “China” of East Asia.49

With his China poblana, Galán exploits the semantic confusion that her name evokes, reorienting her nationality from Mexican to Chinese and making her gender malleable. As scholar Jeanne L. Gillespie explains regarding the origin of the icon’s name, “china does not signify Chinese, but corresponds to the term china or chinaca from the Quechua word used in Colonial Spanish America for slave or servant girl.”50 Linked to the China poblana in the popular imaginary is the historic seventeenth-century Catalina de San Juan, an Asian slave/servant woman from Puebla who was originally from India, not China, and unlike the subsequent China poblana type, she was not a mestiza (of mixed indigenous and Spanish blood). She was a convert to Catholicism, champion of the rights of the poor, and led an exemplary life of piety, asceticism, and good works. If the virtuous San Juan represented the seventeenth-century China poblana, in the nineteenth century she had transformed into an “independent, self-sufficient…and possibly scandal-provoking woman,”51 while in the twentieth-century, her figure clothed in her colorful costume, was one of consumerism-widely used to sell Mexican beer and food products.

Not only with his adapted China poblana, but in his presentation of Los cómplices (The Accomplices) (Fig. 6) of 1987, Galán acknowledges the theatri- cality of the staging of the national. The painting’s protagonist is the charro, the horseman, who during the late nineteenth-century Porfirian era represented dominant masculinity as the hacendado patriarch of the rural hacienda and everything under his purview; while Galán could easily relate the charro figure to his hacienda-owning, cattle-ranching father, Julio Galán de la Peña (b. 1923-d. 2002), the artist assumes the charro identity through self-portraiture, deflating its virility. Galán intended the crowded, static, and flat (in its perspective) canvas to evoke the cheap carnival photo backdrop. Additionally recalling the anatomical awkwardness of a nineteenth-century provincial portrait, the artist inserted his face atop the cardboard-stiff charro costume, the adult-sized head too large for the body.52 As historian Ricardo Pérez Montfort describes, “The charro was and continues to be distinguished by his immense sombrero, tailored pants with silver buttons down the sides and embroidered vest, together with his sarape, spurs, lasso, and of course, his horse.”53 High- lighted is the candy-colored palette of the Saltillo sarape hanging from the charro’s arm, its stripes echoed by a second hand-woven blanket covering the floor. The artist has desecrated the red interior walls by scrawling in black ink a highly subversive message of destruction; incorporating a floor-to-ceiling block of upside-down text on the left-hand side of the composition-the jilted lover spews a tirade of threats that he wants to burn everything in sight, from a museum to his lover’s face. The latter is hardly the dry, straight-for- ward biographical information that would be included on a cartouche typical of Colonial Era and post-Independence portraiture, but rather, confirms an underlying angst of post-modern discontent.54

Lo popular, and High and Low

Galán’s engagement with lo popular, that which is of the masses, and lo cotidiano (commonplace), was varied and abundant. Describing his collage approach to using everyday materials he stated:

I am always experimenting with many materials: with fabrics, with objects, with stones. I just finished a painting painted on pearls and pieces of metal. I also like to integrate Polaroid photographs. I draw something and I paste it over the paint- ing. I have painted a lot on antique fabrics, wallpaper, plastic tablecloths. I am constantly capturing what surrounds me. I am always taking ideas from everyday objects and I use them for my work.55

Galán’s repertoire additionally included objects laden with symbolism, pat- terns, stickers, figurines, papier mâché maracas, paper doll cut-outs, ceramics, magazines, card games such as lotería (Mexican bingo), and more that nourished his imagery-again, often treated with a Camp-Cursi-Kitsch flair.

Many areas of lo popular captured Galán’s attention. For example, music, from bolero to pop was important to the artist; fragments of song lyrics would find their way onto his canvases, their titles, and he wrote them by hand on the verso of many paintings, such as the above-mentioned Tehuana behind which reads, “Tehuana dame un besito no sea que en un momento me lleve el mismo diablito. Tehuana niña bonita, pareces de mentiritas y solo sé que te quiero tanto tanto que me muero” (Give me a kiss Tehuana for the devil may take me at any moment. Beautiful little girl, Tehuana, you look like you look too good to be true, and I only know that I love you so much that it kills me),” verses Galán added with ironic intention likely from a Mexican folk song or poem. His tastes were eclectic and changed over time, but he had his favorites: Miguel Bosé, Madonna, Mecano (Anna Torroja, José María and Nacho Cano), and Tania Libertad’s boleros, among others, forming personal relationships with many of these musicians.

Galán’s juxtaposition of high and low in his surroundings and in his artwork was important to him. “He had many objects,” recounts Galán’s first gallery representative, Guillermo Sepúlveda; “he mixed what was cheap with what was very expensive.”56 He puzzled, “How could a boy age 18 or 19 live with 400 objects around his bed? Moreover, each one represented something, a memory, a story, music, fragrances, lights, candles, religious objects, all in a mix.”57 Galán enjoyed displaying Border Kitsch aesthetic side by side with a cultured taste, inherited from his mother María Elisa Romo (b. 1930-d. 1999) and her father/his grandfather Adolfo E. Romo (b. 1907-d. 1976), for collecting antiques such as porcelain dolls, porcelain doll furniture, tortoiseshell boxes, and jewelry, among numerous other kinds of items. Refinement and tackiness (lo cursi) could hold the same value for Galán, who began collecting at a young age. “What I did inherit from him (Adolfo) was a passion for collecting antiques and rare items […]. I also inherited the taste for acquiring things from my mother, or say, the taste for good things, if they can be called that, or refined. I am sure that trait came from her,” explained Galán.58

Galán’s practice of visiting antique stores and flea markets was recorded in a photograph taken in Manhattan’s Meat-Packing district in the spring or fall of 1990 as he returned home to his apartment on Horatio Street accompanied by his friend and assistant, fashion model Luisa Peña. Resting on the ground at his side is a seascape and a bag of items that he found at The Annex Market in on West 25th and Sixth Avenue in Chelsea, the flea market that they regularly frequented on Sundays.59 This pastime he had shared in common with Andy Warhol (Fig. 7); they shopped together in New York City in the mid-80s just prior to Warhol’s death in 1987. Warhol would at times buy Galán those objects, which the latter found he could not afford, that he wanted to incorporate in his artwork.60 One day they were browsing when Galán discovered a box full of magician’s knives from the 1940s; “they were toys, the kind where it looks like you are being stabbed but it is fake,” he explained. Of the 70 knives, he could only buy one or two. Warhol bought the whole lot and sent it to Galán later that day as a gift.61 Those knives are likely the very ones incorporated at the base of the painting Intentaré (I Will Try) (Fig. 8), punctuating Galán’s attack on religious spectacle. Galán sits, his Mickey Mouse gloves covering his hands while he chokes himself performatively.

7. Julio Galán with Andy Warhol, mid-1980s. Photograph: Unattributed. Courtesy of and reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

8. Julio Galán, Intentaré (I Will Try), mid-1980s. Mixed media on canvas, ca. 1.52 × 1.52 m. Photograph: Unattributed. Courtesy of and reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

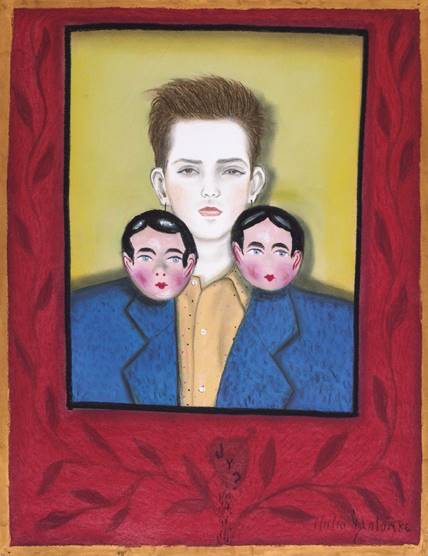

Galán often visited Sepúlveda’s second home in the colonial town of Villa de García northwest of Monterrey. The Spanish-style villa of ten rooms or more, courtyards and gardens was built in 1840. Its adobe walls and thick viga ceilings hold a treasure trove of Mexican folk antiquities, both secular and religious, that Sepúlveda collected. Built-in cupboards (alacenas) are filled with objects such as retablos and ex-votos, plaster mold figurines (baby Jesuses, creche animals, boxers, bull fighters, and monkeys),62 mid twentieth-century portraits of the dead (fotoesculturas), while walls, glass display cases, floor space, and furniture surfaces boast life-size carved wood santos or bultos of the wounded, bleeding Christ with articulated limbs, decorative chests (baúles de laca), embroidery, huipiles (embroidered clothing), money banks (alcancías), stuffed peacocks, small birds under glass, and a leopard, tree of life sculptures, figurative pulque jars, and more.63 That Galán spent time at the house in the mid-1990s is recorded in a spontaneous mural that he painted on one of the walls that he dedicated to his friend, “para Guillermo Sepúlveda.” Many of Galán’s inclusions of popular and folk art elements have their source in Sepúlveda’s collections, such as the decorative frame in Me quiero morir (I Want to Die) (Fig. 9), which draws from lacquerwork from Guerrero (Fig. 10), or the androgynous, pale-skinned, blue-eyed maracas (Fig. 11) from Jalisco that hang as earrings in the artist’s self-portrait, Y nadie (And No One) (Fig. 12) of 1986.

9. Julio Galán, Me quiero morir (I Want to Die), 1985, oil on canvas, 1.32 × 1.87 m. Photograph: The author. Reproduced with permission from the Galán Family.

10. Baúl (chest) in Guillermo Sepúlveda’s home in Villa de García, Nuevo León, ca. early-to-mid twentieth century. Photograph: the author.

11. Maracas, Guillermo Sepúlveda’s home in Villa de García, Nuevo León, twentieth century. Photograph: the author.

12. Julio Galán, Y nadie (And No One), 1986, pastel, 65 × 50 cm, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. Photograph: Camilo Garza y Garza. Reproduced with permission from the Galán Family.

Upon seeing in Sepúlveda’s collection a “crying child” (Fig. 13), a form of sculptural portraiture of disembodied, European-looking children’s heads with distorted faces and open mouths, Galán acquired a similar one, affixing it to his painting Mi segundo pecado (My Second Sin) (Fig. 14) of 1998 of a fallen angel.64 These compelling objects made from molds with clay and plaster were produced in Saltillo, Coahuila in the 1940s and 1950s. Galán’s approach of combining the three-dimensional found object on a canvas surface recalls Germán Venegas’ (b. 1959) escultopinturas (Sculpture-paintings) or low-relief paintings of 1983-1985, such as Santo ángel and El ángel y el diablo.65 While Venegas offers his brash meditation on the violence of syncretic religion and mestizo culture, or the merging of aspects of indigenous tradition with im- posed colonialism, Galán personalizes his version of the tension between the sacred and profane with the text “mi segundo pecado” (“my second sin”), which he adds in the upper left-hand corner of the painting.66 The full-length figure reads, as is typical of Galán’s oeuvre, as a self-portrait; while a self-refer- ential painting, Galán points to the sin that followed the original sin of Adam and Eve-the “second sin” is that of covering up or hiding from one’s actions deemed to transgress divine law.

13. Niño llorón (Crying Child) from Saltillo, Coahuila, 1940s-1950s, clay and plaster, ca. 20 × 15 × 15 cm. Guillermo Sepúlveda’s home in Villa de García, Nuevo León. Photograph: the author.

14. Julio Galán, Mi segundo pecado (My Second Sin), 1998, oil and montage on canvas, 1.9 × 1.3 m. Private Collection. Photograph: Camilo Garza y Garza. Reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

Sepúlveda’s wife Kana Fernández, who wore huipiles, had a collection of Oaxacan and china poblana clothing, which Galán studied at the Villa de García house;67 he also took Polaroids of his sister Lissi in that clothing as source material for the more naturalistic ¡Quién te manda! (Who Forced You to Do It!) of 1999 and Retrato de Elizabeth (Portrait of Elizabeth) of 2000, paintings featuring her in china poblana dress.68 A direct example of Galán’s “lifting,” appropriation, or reinterpretation is exemplified by the artist’s faithful study of a late nineteenth to early twentieth-century ceramic pulque portrait pitcher from Barrio de la Luz, Puebla (Fig. 15) with dripped glazing decoration that Galán borrowed from Sepúlveda’s collection.

15. Unidentified artist, Pulque vessel from Puebla, late-nineteenth/ early twentieth century. Ceramic, ca. 61 × 30 × 30 cm. Guillermo Sepúlveda’s home in Villa de García, Nuevo León. Photograph: the author.

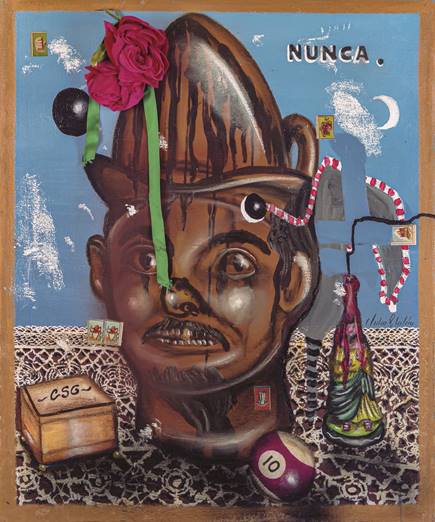

Marion Oettinger explains that such pitchers were utilitarian, and not specifically portraits of individuals, but mold-made for the purpose of producing multiples made distinct by accidental glazing.69 The popular beverage representative of the poor indigenous and mestizo classes, pulque was consumed in pulquerías, “rough places (for men) with urinals at the base of the bar where one could drink and urinate at the same time,” found in lower-class barrios.70 Among the various kinds of pulque pitchers (some taking the shape of a Victorian woman’s shoe, for example), are those with Indian headdress, pointing to pulque’s association with mexicanidad of the final years of the Porfiriato. Produced for celebrations, Sepúlveda’s portrait pitcher may well represent a soldier, in helmet, of the 1862 battle of Puebla honored annually in Cinco de mayo festivities. Galán took the pulque pitcher to his studio to paint the fearsome warrior in Nunca (Never) of 1993.71

Cerámica, Provincial Portraiture, Wordplay, and Feathers

A large sculptural head with a conical helmet and short neck, all of a rich bronze color stands centrally on an embroidered tablecloth. Wide-eyed and teeth bared, black stains drip freely down the figure’s face. A decorative box inscribed with the letters “A” (Adrian) and “E” (Esther), also sits on the table as well as the number 10 burgundy pool ball (which, to be correct, should be blue as the burgundy stripe belongs to the number 15), and a religious candle in the figure of a saint. A tacky red rose made of fabric with a green ribbon is fastened to the canvas. The word “nunca” (“never”) painted prominently in the upper right-hand corner, appears significant, but of what?

Sepúlveda pointed out that Galán painted Nunca concurrently with Sofía vestida de china poblana (Sofia Dressed as a China Poblana) of 1993, a painting commissioned by then-President Carlos Salinas de Gortari’s administration for the President’s Collection housed in Los Pinos, the Presidential residence in Mexico City.72 Taking inspiration from nineteenth-century provincial por- traiture and studio photography of types, Galán has painted a young girl, his sister Sofía, full-length and frontally, in china poblana dress, which he has decorated with jewel-like sequins affixed to the canvas. Initially rejected, commissioning agents found unacceptable Galán’s inclusion of the President’s initials (CSG) on the china poblana’s rebozo; when he eventually altered these to appear like abstract decoration, the work was finally accepted.73 Sepúlveda suggested that Nunca’s imagery-the figure’s façade and the billiard ball-was a political dig pointing to a “negative presence” in relation to then-President Salinas.74 (“Nunca jamás volverás a ser presidente”/ “Never again will you return as president”)? Salinas’ tenure ended in 1994 in scandal, the collapse of the Mexican economy, self-exile, and his brother Raúl’s incarceration as he was accused of tax fraud, illicit enrichment, and murder. Salinas employed culture as a means to improving his country’s foreign image in his campaign of neo-liberalism and privatization while he negotiated the National Free Trade Agreement (nafta) in 1991-92.

However, Galán painted Nunca at the time that the Grupo Financiero Serfín sponsored a major publication for the artist reproducing the painting within its pages. At that time the box on the left-hand side of the canvas was unmonogrammed; subsequently Galán added its decorative elements with the letters “A and E” in honor of his patrons, Adrián Sada González, and his wife, Esther Cueva de Sada. Adrian Sada, head of the glass corporation Vitro, was also president of Serfín, his family having won the bank’s concession in 1992 when President Salinas privatized the national banks. In the same year as Nunca, which Galán donated to Serfín along with two other paintings as payment for the publication, Galán painted El mago Adrián (Adrián the ma- gician), an orientalized portrait of Adrián, his wide-set eyes similar to Nunca’s warrior’s.75 Accompanying Adrian’s tender portrait is text that begins, “Once upon a time there was a prince,” and ends, “My life lives in you, love.” Whose voice (Galán’s? Esther’s?) proclaims their love for the prince? Perhaps “Nunca” is also a statement of the impossibility of love: (“Nunca jamás estaré contigo”/ “Not ever will I be with you”)? It is possible that in this thematic vein Galán’s intent was to invoke the song “Nunca” written in 1927 by poet Ricardo López Mendez and sung by Guty Cárdenas, which proclaims:

I know that I will never

kiss your mouth

your flaming purple mouth

I know that never

will I arrive at the crazy

And passionate source of your life.

I know that uselessly I venerate you,

how uselessly the heart invokes you

but nonetheless I love you

but nonetheless I adore you

although, I can never kiss your mouth.76

Galán’s love interest is unattainable. Fascinating is, not only the painting’s source of inspiration in the arte popular ceramic pulque jug and Galán’s trans- formation of the three-dimensional object into two-dimensions and a new context, but his juxtaposition of image and a single word “Nunca,” opens up a world of intrigue.

But this story does not end here. Camilo Garza y Garza, long-term pho- tographer of Galán’s oeuvre guards an early stage of Nunca (Fig. 16) in his photographic archive. All of the imagery remains the same as described above, with the important exception of the monogram on the box. Across the top of the box Galán has painted the letters “CSG,” a pointed reference to Carlos Sa- linas de Gortari; Galán’s choice to then hide the direct reference to President Salinas could be viewed as a self-censoring move to avoid potential political repercussions, but on the other hand, such erasure was in keeping with the artist’s constant play with what content he revealed, and what content he hid from the viewer.

16. Julio Galán, Nunca (Never), early stage, 1993, oil on canvas, 80 × 90 cm. Mauricio Jasso Collection, Spain. Photograph: Camilo Garza y Garza. Reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

In the early 1980s Galán succeeded in bartering with Sepúlveda for El niño del violín (Violin Boy), an undated painting from Nuevo León in the style of provincial funerary portraiture commissioned by the subject’s family. The haunting, full-length portrait of a young boy dressed in a suit, violin in hand, was certainly in remembrance of the deceased adolescent Gregorio Alanís

González (1895-1908). A life-size marble sculpture of the violinist, likely produced by Italian-born, Monterrey resident Michele Giacomino Manchineli (1862-1934), based on the above painting or a photographic source, crowns the boy’s tomb in Monterrey’s Panteón del Carmen cemetery. El niño del violín’s frontality, pallid visage, youth, carefully parted hair, and isolation were conceptually and stylistically important to the ways in which Galán approached the figure in his art. Autorretrato (pianista sin piano) [Self-Portrait (Pianist Without a Piano)] of 1993, for example, is one of many of Galán’s works that embodies these qualities; also invoked is a sense of loss or absence, as, defying expectations, the musician has no instrument to play. Galán’s references and sources were consistently eclectic; not only does Autorretrato (pianista sin pia- no) draw from the formal lessons of nineteenth-century provincial portraiture, as Mexican vanguard artists Kahlo and Izquierdo did long before him, but just as easily takes inspiration in a contemporary film such as Amadeus (1984), whose flamboyant, outrageous protagonist played by Tom Hulce, Galán would have identified with, and whose Rococo dress Galán mimics here.

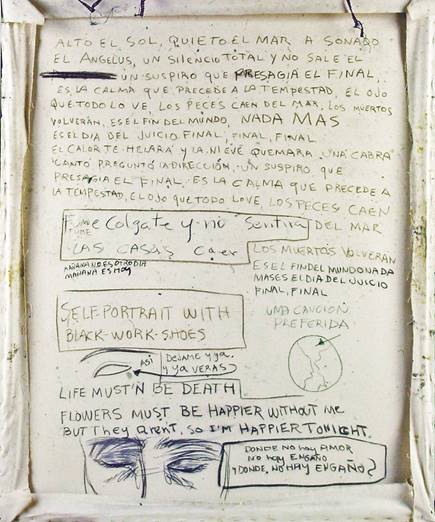

Galán achieved complexity in his paintings combining text with image. Using wordplay, epigrams, rebuses, and fragments in his dialogical art, he enjoyed secret code and language, rewarding with inclusion and knowledge of his personal world that viewer who could discern meaning. Furthermore, as noted previously, he often wrote text and drew images on the back of his can- vases adding yet another layer of meaning typically hidden from view when the work hung on a wall. Take, for example, the enigmatic Autorretrato con zapatos de trabajo negros (Self-Portrait with Black Work Shoes) of 1990, as Galán has titled the painting in English on its reverse (Fig. 17). He has covered the back of the canvas with hand-written lyrics from the brazen, Spanish-Mexican, punk-goth artist Alaska’s (Olvido Gara, b. 1963) oddly upbeat song “El fin del mundo” (The End of the World) released in 1986, identifying it on the canvas as “una canción preferida” (a favorite song). Galán then drew an eye and wrote “Así. Déjame y ya. Y ya verás” (Like this. Leave me and that’s it. And you’ll see) and next to the drawing of a face with closed eyes he wrote in English the message “Life must’n [sic] be death. Flowers must be happier without me. But they aren’t. So I’m happier tonight,” followed by “Donde no hay amor, no hay engaño y ¿dónde? no hay engaño” (Where there is no love there is no betrayal and where, is there no betrayal?). The front of the painting with its Latin alchemical saying “Visita interiora terrae rectificando invenies ocultem lapidem” (Visit the interior of the earth, and by rectifying you will discover the hidden stone) paired with a white and black swan, their necks intertwined to form a double helix, and a pair of shoes affixed to the canvas create an incongruent whole that is at once spiritual and secular.

17. Julio Galán, Autorretrato con zapatos de trabajo negros (Self-Portrait with Black Work Shoes) (verso), 1990, oil on canvas and mixed media, 1.48 × 1.83 m. Courtesy of the Galería omr. Reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

One childhood source for Galán’s fascination with word puzzles was a red carcacha (jalopy car) (Fig. 18), likely a Ford Model A Cabriolet from 1930, that his family owned in Múzquiz in the late-1960s when the artist was nine or ten years old that they would drive around town. The convertible was completely covered with “Lizzie labels,” witticisms and slogans that were painted on Model T Fords, but in this case, in the Spanish language and with white, yellow, and black paint.77 Lissi Galán explained that one had to puzzle-out the meaning of the sayings such as “Así se B + 9 cito” meant “Así se ve más nuevecito” (In that way it appears newer), or “tdj” meant “Te dejé” (I left you) or “tbc” read as “Te besé” (I kissed you).78 Just such an epigram served as the title for the striking self-portrait Noe stenchin gando, text painted in all capital letters on the bottom right-hand corner of the large canvas in the otherwise empty field with the exception of Galán’s suspended face, centered like a target. When pronounced one can decipher the slang phrase “No estén chingando” (Don’t fuck with me). The former epigrams (tbc, tdj) can also be clearly discerned, for example, lettered on one of Galán’s sculptures from the late 1980s (Fig. 19).

18. Red jalopy, likely a Ford Model A Cabriolet from 1930, owned by the Galán Family in the late-1960s. Photograph: Unattributed. Courtesy of and reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

19. Julio Galán, Untitled, ca. late 1980s-early 1990s, ceramic and metal, 180 × 70 × 70 cm. Photograph: Camilo Garza y Garza. Reproduced with permission of the Galán Family.

While painting was the artist’s primary medium, he produced a body of at least twenty-five ceramic works, heretofore relatively unknown, that both dialogue with his painting and are compelling aesthetically and contextually. Among these were a series of high-fired and glazed ceramic globes or orbs (globo/esferas) topped with expressive heads, their round bodies the satisfying circumference of a human embrace; nestled on metallic bases, which raised the forms to eye-level, some were functional-to hold flowers or serve as ashtrays. Among the many treasures at Sepúlveda’s Villa de García home are two “gordo” ceramic pulque pitchers (Fig. 20) that were sent to him by mistake, after Galán had purchased them in Puebla.79 With their spherical bodies and small heads, these were certain to have been the inspiration for Galán’s sculptural orbs, seven of which were presented at the artist’s first solo exhibition with the Annina Nosei Gallery in 1988. Not well understood by reviewers at the time, they were dismissed by the Village Voice as low art, “having the garish trashi- ness of Mexican souvenir ceramics.”80 while the New Yorker Magazine viewed them as high art, or “marvelously high-flown rococo ceramics.”81

20. Pulque vessels from Puebla, late-nineteenth to twentieth-century, ceramic, ca. 33 × 38 cm. Guillermo Sepúlveda’s home in Villa de García, Nuevo León. Photograph: The author.

Developing this body of sculptural work over at least five years, Galán described not only the utter sense of loss that he felt on accidentally breaking his favorite one, but also the level of communion that he experienced with his artwork:

I had one that was my favorite. A shepherd holding his hand forward from which fell iridescent threads. In his head he carried a pale green candle and around his waist a long red ribbon that dragged. That night I wanted to put it in a room where there is no electricity. I was anxious to see it installed on a shelf and to see this iri- descent effect, where (the globe) illuminated by the light of the candle with moving shadows projected on the wall, but that did not happen. Going down the stairs from my studio, I tripped, and the sculpture fell. It shattered. It shattered. I do not want to describe what I felt and I cannot.82

Galán’s personal, emotive, inventive, and highly contemporary spheres conceal, rather than announce, their debt to these Mexican ceramic pulque vessels. Two spheres exemplify Galán’s use of the language of types in sculpture.

A charra or adelita (horsewoman or female fighter/camp follower during the Mexican Revolution) rides a horse sidesaddle on top of one of the spheres, below which appear the artist’s prominent initials, “JG.” In the second globe, a boy wears a gold sombrero and a purple bow tie, his spherical body abstractly decorated and riddled with numerous gold cylindrical protrusions, perhaps openings where flowers can be inserted. These Galán produced at Roberta Brittingham Sada’s ceramics workshop, Taller de Arte y Diseño, in the ceramic tile manufacturing company, Cerámica Regiomontana, in the late 1980s and early 1990s in Monterrey, Mexico. As Brittingham recalls, Galán age 14 first visited the Taller with his mother one day when factory workers were experimenting in the workshop with hand-painted designs and varying color palettes on ceramic tiles intended for wall murals.83 The workshop became increasingly professional, with ceramicist Gerda Gruber (b. 1940) teaching factory employees classes in porcelain, and how to work with different clays and glazes. When Galán returned years later as an emerging artist, he was excited by the Taller’s artistin-residence program; he arrived with drawn sketches for sculptures that he wanted to create in clay, having had no prior experience with the medium. Artists in the Taller would work with Galán’s designs to create the hand-built sculptures from slabs of clay. Once fired and covered with a white base glaze, Galán would paint and finish them.

In addition to Galán’s play with Mexican types, artesanía craft, provincial portraiture, popular music and poetry, and ceramics, he produced at least two paintings incorporating the unusual material of feathers. The entire surface of Múzquiz, 1997 of 1989, a commanding canvas at 2.28 × 1.77 metres, is covered with feathers; these the artist dyed and spray-painted to achieve an impressionist seascape complete with moon, horizon line, moonlight reflected on water, a boat, trees, birds, and a small house in mauves, purples, and yellow.84 The artist described using a bag of white feathers that his sister Lissi sent from Mexico to his West Village apartment in New York City; it left “a hell of a mess.”85 High and low art collide in Múzquiz, 1997 (which, like Niña triste porque no se quiere ir de México, he also post-dates) both in material and imagery.

The nostalgic, saturated memory of Galán’s childhood home at once, again, evokes the mass-produced popular imagery of the romanticized mid twentieth-century calendar chromolithographs, while simultaneously invoking the arte plumario (featherwork) of the pre-Columbian era employed by elite Aztec amanteca (feather workers who lived in the area of Amantla in Tenochtitlan) to construct shields and headdresses, as well as the tequitqui (Colonial artwork and architecture that shows evidence of an indigenous hand) Colonial era feather mosaics of Christian saints that indigenous artists produced under Catholic Church direction. The former were created with feathers collected from hummingbird, quetzal, and other precious birds, while Galán’s experimental approach and his secular landscape locates his feather painting firmly in the realm of the contemporary regardless of a reviewer for the New Yorker Magazine referring to Múzquiz, 1997 as a “post-apocalyptic rendition of an ancient Mayan pillow fight.”86 With Múzquiz, 1997, Galán’s Camp-cursi-Kitsch with its sense of artifice, sentimentality, tactile nature, exaggeration, and nostalgia is on full display.

To reiterate, throughout Galán’s career, Frida Kahlo’s name was frequently raised by scholars and art critics as his parallel especially in the two artist’s shared interest in self-portraiture, Catholic imagery, costuming, bodily fluids, preoccupation with death and pain, and queerness.87 A debt to ex-votos and retablos has been identified in both artist’s work. Kahlo and husband Diego Rivera collected these popular expressions of devotion, covering the stairway walls of their home, the Casa Azul, with them, Salon-style. Kahlo at times resorted to the ex-voto compositional format incorporating narrative text that added a documentary dimension to her portraiture. Galán considered his use of text on his canvases spontaneous: “my paintings are a kind of diary; if I look at them from first to the last, I see my life reflected,” he stated.88 Galán, who worked on a much larger scale than Kahlo did, avoided echoing the rigid ex-voto format, or precise narrative, but rather, incorporated fragmented text on his canvases in a graffiti-like manner and/or with a rotulista (sign-paint- er) quality, often made illegible by the artist because of erasures and strike- throughs, and its backwards, upside-down, or coded presentation.89

Lo popular: Countercurrent vs. Postmodernism

In considering Galán’s relationship with Mexican popular art, it is important to revisit the motivations of those artists of the immediate post-Revolution who engaged with the revalorization of arte popular or indigenous craft as a means to create new visual languages. Gerardo Murillo (Dr. Atl) published his two-volume anthology on Mexican folk arts and crafts, Las artes populares en México in 1921 (reprinted in 1980) to accompany the first major exhibition of its kind presenting more than 5,000 objects in Mexico City and subsequently in Los Angeles.90 Dr. Atl’s efforts to re-valorize arte popular in its various forms had a significant impact on artists of the immediate post-Revolution who advanced Mexican modernism.

Following the 1911 student strike at the Academy of San Carlos in protest at the institution’s conservative, Eurocentric program of study, and the subsequent development of alternative approaches to art study, Mexican artists in the 1920s broke away from the Academy’s neo-Classicism to pursue avant-garde strategies. Employed as rural art teachers by President Álvaro Obregón’s Ministry of Education, Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, Julio Castellanos, Antoniio Ruiz, Rufino Tamayo, Carlos Mérida, Agustín Lazo, and others of the contracorriente, helped reformulate art pedagogy to be more inclusive across social classes. They turned to the local, indigenous subjects for thematic and formal approaches while drawing lessons from the European vanguard, particularly the School of Paris, as means to renovate national art. This effort was spear-headed by Alfredo Ramos Martínez’ implementation of his Open- Air School project, and Adolfo Best Maugard’s new pedagogical program, the Pro-Mexican Art movement, in which the above artists and others both taught, and incorporated, if for a time, into their personal art practice.

Abraham Ángel (b. 1905-d. 1924), a protégé of Adolfo Best Maugard and Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, applied the decorative techniques of arte popular to portraits of his family; he attained highly patterned compositions with shallow depth of field and dramatic shifts in scale painted with an unnaturalistic, almost fauvist palette, but retaining a certain opacity through his use of tempera paint. Galán’s appreciation of Ángel’s approach can be noted in his pastel Sofía of 1986 in comparison with Ángel’s La chica (Retrato de Amelia Card Valdés) [The Girl (Portrait of Amelia Card Valdés)] of 1924, each work apparently depicting the corresponding artist’s sister as indicated by their titles. Similar is their enjoyment of decorative pattern, the shallow space between figure and ground, the placement of the subject centrally and against wallpaper with tacky, framed landscapes nailed to the wall, and a focus on dress and accessories. But Galán literally extends his content by giving his subject an impossibly tall, stiff coiffure supported by ribbons and pearls. He then not only repeats this imagery in three-dimensions as one of his globe ceramic sculptures (titled M. Posewhite, likely a nod to his former muse Marcela Postlethwaite Sepúlveda) dons the same stout hairdo, but also reproduced this look, likely in the late 1980s, with his model Cristal Martínez in a performative action as Mauricio Jasso recounts: “Julio arranged her hair and make-up giving her a Madame Pompadour hairdo that measured almost a meter in height. He then took her out to eat tortas (Mexican sandwiches). Cristal had to get into the car with her head sideways. Can you imagine how the diners reacted?”91 Forward-thinking in his style, this look is echoed a decade later by one of Galán’s favorite fashion designers, Yohji Yamamoto in his Autumn-Win- ter 2011 show in Paris where his models wore their hair in cotton-candy-like whipped hairdos likely woven with Merino wool, their colorful coif standing straight up.92

Galán, at a much later place and time, was looking at some of the same sources of inspiration as Mexican artists of the 1920s and 30s to include ex-votos and retablos, but also provincial portraiture, figurative functional ceram- ics, and textiles; while these vanguard artists turned to these sources in their drive to build a new national art, Galán, did so a half-century later with a transgressive, non-conformist, and queer point of view. Mandarín of 1993 exhibits many of Galán’s transgressive strategies discussed above with his camp- Kitsch-cursi approach as he collapses boundaries of race, gender, and high and low art. As I have argued elsewhere:

Galán painted his full-length self-portrait in a skirt, long jacket, and Chinese head- dress as he animated the number sixty-two card, “El Mandarín” from Mexican lotería (bingo). This painting not only drew from lo popular, but would have been inspired by a collage of sources, from Galán’s attraction to the androgynous dress of the Mandarin, to the artist’s fascination with the Hollywood film The Last Emperor of 1987, and the appeal of a range of Chinese imports, whether from the border town Mexicali or purchased from Sanborns, or Chinese inspired Mexican artesanía from Michoacán.31 Here…Galán appropriates this lotería type to resignify heteronormative views of lo mexicano as gender fluid and transcultural.93

Galán’s Camp-cursi-Kitsch sensibility is further noted in the decorative wallpaper in Mandarín that serves as backdrop. Here and in the aforementioned China poblana of 1987 Galán has Orientalized his content as a means to spotlight aspects of a hybrid Mexican culture. The paintings Té con la reina entre azules (Tea with the Queen Amidst Blues) of 1997, whose title likely plays off of the sixteenth-century Spanish pottery center, Talavera de la Reina, and Mentes azules (Blue Minds) of 1990 evidence the artist’s fascination with Chinese ceramics, whether Border tourist kitsch or ancient vessel. The blue designs simultaneously evoke Chinese motifs, as well as traditional Mexican white and blue glazed talavera. Finally, as with Mandarín, Galán reveals stereotype, and racial and gendered identity as malleable, rather than fixed, through self-portraiture in such paintings as the major canvas Chinese of 1990, Chino con arracada (Chinese with Teardrop Earring) of 1992, and You Are Going to Finish Me Off of 1995.

At the symposium Fashioning Identities: Types, Customs, and Dress in a Global Context held at Hunter College, cuny in the fall of 2013, as I presented the lecture “Playing the Devil’s Advocate with a Twist: Julio Galán and Lo mexicano,” I emphasized to the audience, as I have here, that Galán’s overtly mexicanista paintings in which he incorporated Mexican national imagery in a seemingly direct way were but a small number of perhaps ten canvases within a vast oeuvre of his some estimated 1,000 artworks.94 These Mexicanist paintings have been considered representative of Galán’s production, and were absorbed into neoMexicanism (neomexicanismo), the post-modern tendency in Mexican art that revisited known signs of identity, icons, and historic figures and periods (pre-Columbian, Colonial, Independence, Revolution), blurred the boundaries of the sacred and the profane, and high and low, with a sometimes nostalgic, often irreverent approach. Following the precedents of Lowery S. Sims and Francesco Pellizzi, I emphasized Galán’s international positioning, and his crossing of multiple borders geographically, conceptually, and in his image-making. I put forth that this he accomplished with a transgressive, non-binary intent.95 The formal analysis presented here of several of these works identifies the variety of lo popular that Galán engaged with, from the language of Mexican types, to calendars, studio and souvenir photography, music, everyday domestic objects, ceramics, laquerwork, provincial portraiture, games such as lotería, textiles, and more, as well as his particular Camp-Cursi-Kitsch approach, which argues that fixed identity is artifice.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)