Interreligious experience between Christianity and popular Buddhism is an emerging approach in the studies of Catholic missions in early modern Japan. This perspective challenges us to rethink Japanese Christianity, by calling into question traditional historiography interpreted "from above," namely, from the viewpoint of European missionaries and local ruling class. Historians influenced by the Annales School and researchers of comparative religion have explored the Kirishitan networks, practices and beliefs "from below," that is, from the perspective of ordinary people, who were the true support of the Japanese Church.1

Even though the term Kirishitan derives from the Portuguese word christão, this concept is not an exact synonym of "Christian," but refers to a world of faith unique to Japan. The Kirishitan beliefs and practices were formed by the interconnection between Japanese religion -which mixes elements from Shin-toism, Buddhism, and Taoism- and the Catholicism transmitted from Europe from the mid-16th to early 17th centuries. Its religiosity is based on a belief system predicated and assimilated in the Japanese language. Hence, Ikuo Higashibaba points out the importance of clarifying how Japanese converts perceived the similarities and differences of a new religion by comparing with native religious traditions, and thus to construct a "history of acceptance" of the Kirishitan beliefs.2

In accordance with this perspective, it is pertinent to study the practices and beliefs linked to the Holy Rosary in Japan, since both Buddhism and Catholicism share a similar custom of using strings of beads for their respective prayers. Catholic rosary beads were called kontatsu in Japanese, a term derived from the Portuguese word contas. Its etymological meaning coincides with that of Japanese Buddhist string of beads, called juzu (lit. "beads to count"). The spread of specific prayer formulas was related to the popularization of faith in both religions. In the light of their confluent points, some questions arise: how did the Japanese converts accept Catholic rosary and blessed beads? To what extent was the conversion of Japanese people thorough?

This paper focuses on the origins, spread and interfaith beliefs of the Christian prayer beads, that is, the devotion of the Holy Rosary and its variants. The Franciscan Crown is also known as the Rosary of the Seven Joys of Our Lady. According to the Franciscan historian Luke Wadding (1588-1657), the origin of the Seraphic Rosary dates back to the year 1422. A young Franciscan novice named James decided to abandon conventual life and return to the secular world. Before entering the order, he used to offer a garland of natural flowers to the statue of the Virgin Mary, while, in the convent, he could no longer continue this devotion. But the Virgin appeared to him saying not to be sad for this reason. Instead of giving her wreaths of flowers that wilted soon and could not be found anywhere, she asked him to weave for her a wreath of prayer, which would never wilt and stay fresh forever. Thus, Mary suggested, the novice should recite in honor of her seven joys.3

Similarly, the Marian prayer of the Order of the Hermits of Saint Augustine is called the Crown of the Virgin of Consolation and Cincture. The holy Mary used a cincture throughout her life in accordance with the custom of Hebrew virgins. She was also buried with it. According to a pious tradition, at the time of the Virgin's death, all the apostles were providentially gathered together with her except Saint Thomas, who arrived in Jerusalem three days later. To fulfill his desire to see the Virgin, who had already been buried, the tomb was opened. To everyone's surprise, there was no longer the body of the Virgin, but only the canvases with which her body had been wrapped, and the cincture, which Mary had used all her life. Saint Thomas recognized this holy relic and kissed it with great respect.4

At the end of the 4th century, the devotion to the holy cincture of the Virgin Mary was resuscitated thanks to Saint Monica (332-387), mother of Saint Augustine (354-430). Saint Monica was in the greatest sorrow for the death of her husband, Patricius, and for her son's paganism before his conversion. To lighten her grief, she remembered the loneliness of Mary after the death of her Divine Son, prayed to Our Lady and asked her to show the manner of dressing that the Virgin had used in this life. Her prayer and wish were heard. The Holy Mother appeared to her dressed in a black habit and girded with a cincture, and said, "This is the dress I wore when I was among mortals, and you will wear it as a sign of my devotion."5 Mary also promised that "whoever wore this belt would receive her special consolation and protection."6 Sometime later, Augustine had a vision of divine grace, and converted to Christianity. He received from Saint Ambrose a monk's habit and the cincture which Saint Monica had prepared for him.7

This work is organized in four sections. The first presents parallels between non-Christian and Christian traditions concerning the use of strings of prayer beads. The second addresses formation and development of prayer for the Rosary. The third mentions the spread of Catholic prayer beads in the overseas missions until reaching Japan by the two opposite maritime routes opened up by the Portuguese and Spanish empires. Finally, the fourth analyses the intersection between Buddhist and Kirishitan prayer traditions.

A close connection between both religions is also seen not only in the use of strings of beads but also in the images. In particular, two Japanese Jesuit paintings depicting The Virgin with the Child and their fifteen mysteries and Loyola and Francis Xavier, show similarities with the composition and function of the Taima mandala of Pure Land Buddhism. This question has been analyzed in my article entitled "El Rosario y el juzu: experiencias interreligiosas del periodo Kirishitan."8 Similarly, I have conducted a formal and iconographic analysis of the images related to the Rosary in my work "Transculturación y sincretismo del Rosario en el Japón moderno temprano."9 This paper provides new information complementing the above.

Links between non-Christian and Christian traditions

From the earliest times various devices for counting prayers were used in different religions. Beads used to have a double function: as object with supernatural power and prayer counter. By exploring the uses of the rosary in Europe, we find that the rosary in hand used for prayer, the rosary used as a necklace, as well as the relationship between the Virgin Mary and rose are derived from ancient traditions in which certain shrubs became sacred to certain deities, or a certain mana, "a sacred impersonal force existing in the universe."10 Thus, by going back to ancient Egypt, headbands and crowns made from sacred trees were what transferred the mana of gods to priests and kings.11

In this way, the oak was linked to Zeus, the laurel to Apollo, the olive to Athene, the myrtle to Aphrodite in ancient Greece. The rose was also associated with the latter goddess, since she emerged from the sea together with roses. Her Roman equivalent Venus, therefore, was frequently described with a rose garland as in De raptu Proserpinae by the Latin poet Claudian (c.370-c.404 A.D.)12 and The Knight's Tale by Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1340s-1400).13

Prayer beads are not exclusive to Catholicism, but were also used among non-Christian religions long before the advent of Christ. One of the most widely accepted theories for the origin of the rosary is the one proposed by Wilfred Cantwell Smith (1916-2000). According to him, the use of the rosary probably spread out from India, and was adopted by different religions along two paths: it was introduced by Buddhism through Tibet, China, and Japan, while entering Christian Europe via Islam at the time of the crusades.14 However, there is also the opinion that although mutual influence cannot be ruled out, it is difficult to determine the origins. Moreover, each religion developed its own tradition.15 Therefore this phenomenon could be considered as cultural parallelism.

On the philological level, the earliest known use of prayer beads in the world is referred to as one of the ten tools of Brahman ascetics in the Jaina canon, most of whose texts have been dated back from the first century BCE to the fourth century CE.16 In this treatise, beads were in two forms called ganettiya and kañchaniyd in Prakrit, a language used in large parts of India in Maha-vira's time. The former is equivalent to ganayitrika (lit. "counter") and the latter corresponds to kdñcana (gold) in Sanskrit.17

In India, the evolution of the rosary as a prayer tool is attributed to the Hindus. Materials and number of beads vary according to the sect and cult. A worshipper of Shiva uses a string of 32 beads, while those of Vishnu use ones with 108 beads; this number later acquired symbolic meaning for Buddhism.18Rudraksha, which literally means "eye of the god Rudra" (i.e. the ancient name for Shiva), is a seed from the Elaeocarpus ganitrus and is used in preferance as a prayer bead in Hinduism, especially Shaivism, while the votaries of Vishnu prefer tulasi beads.19 It is interesting to note a parallel between the rudraksha and the rosary of the Virgin Mary, since both of them are derived from woody plants.20 The Buddhist full rosary consist of 108 beads.21 This number corresponds to the "number of mental conditions, or sinful inclinations, which are to be overcome by the recitation of the beads."22 Instead, the Muslim rosary, called sebha or tasbih, is made up of 99 beads for counting the 99 names of Allah.23

Formation and development of prayer for the Rosary

The cult of the Virgin Mary became increasingly important from the twelfth century on. Collections of Marian miracles in prose were written, as shown by the Miracula Beate Marie Virginis (Ms. Thott 128, Royal Library of Copenhagen), the Miracula Sancte Dei Genitricis Virginis Marie, Versifice composed by the Benedictine monk Nigel of Canterbury (c. 1130-1200), and the Stella Maris of John Garland (d. c. 1253).24 Similarly, the cycle of prayers in honor of the Virgin Mary became rooted in the mid-twelfth century. The custom of decorating a statue of the Virgin with a garland of fresh flowers might respond to a liturgical function and led to substitute beads for flowers.25 The number of prayers recited corresponded to a numerology. The Psalterium Beatae Mariae Virginis consisted in reciting the Hail Mary 150 times according to the number of the Psalms. In its reduced version, Rosarium Beatae Virginis Mariae, the number of recitations of the Hail Mary was 63 times, which coincides with the number of years the Virgin lived.26

In this regard it should be added that the Christian canonical scriptures did not record the death or Dormition of the Virgin Mary. Consequently, there are different traditions regarding the time the Virgin Mary lived on earth. According to the Revelations of Saint Bridget of Sweden (c. 1303-1373), Mary herself revealed to her that she had lived 63 years on Earth,27 while another Catholic tradition says that the Virgin Mary departed this life at the age of 72.28 Therefore, the Franciscan cycle of prayer consists of reciting 72 Hail Marys, as mentioned later.

In the I5th century, the Dominican Alanus de Rupe (c. 1428-1475), born in Brittany, linked the recitation of the rosary with the Virgin of the Rosary by spreading the story of the apparitions of the Virgin to Saint Dominic de Guz-mán (1170-1221). The objective of this miraculous event was to remind him of the prayer of the rosary and to commission him to spread his preaching as an efficient weapon to combat the Albigensian heresy, which had spread through southern and central France during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The first great propagators of the devotion to the Holy Rosary were Rupe, and his follower Jakob Sprenger (1436-1495), prior of the Dominican convent in Cologne. Rupe established a brotherhood of the Rosary, called Confratria Psalterii Domini Nostri Jesu Christi et Mariae Virginis in Douai, France in 1470. Five years later, Sprenger also founded a successful Rosary confraternity in Cologne.29

With regard to the methods of praying the rosary, Rupe claimed that if one prayed I50 Hail Marys every day and marked off every ten of those by one Our Father, the total number of Our Fathers recited in a year (15 χ 365) would equal 5,474, which corresponds to the total number of wounds Christ received on his body during the Passion according to Saint Bernard.30 The basis of the modern Rosary was found for the first time in the Unser Lieben Frawen Psalter, attributed to Rupe and published after his death in Ulm in 1483. The points of meditation on the life of Mary -which were later called "mysteries" by the Dominican priest Alberto da Castello (ca. 1450-1522)31- were reduced from 50 to 15. These were composed of the five joyful, five sorrowful, and five glorious mysteries. Mary's assumption and coronation were combined into a single mystery. However, unlike the current version, the Last Judgment was the fifteenth mystery or the fifth glorious mystery.32

The approval of the granting of indulgence to the confreres of the Rosary by Pope Alexander VI in 1495, was a key event in spreading this devotion in different parts of the world. Simultaneously, the publication of the manual Rosario della gloriosa Vergine Maria, written by Alberto da Castello in 1521, and its reprints contributed to the spread of the fifteen mysteries.33

The further development of this cult was achieved due to the Council of Trent (1545-1563). Within the ecclesiastical renewal of the Tridentine era, different pious practices and images were reviewed and the legitimacy of devotion to the Rosary was confirmed again. Since this was known to have been used as a weapon by Saint Dominic against the heretical Albigenses, the Church employed it as a symbol of struggle and triumph over Protestants and infidels.34 The popularity of the Rosary increased even more after the victory of a Catholic coalition formed by Spain, Venice and Rome against the Ottoman Empire in the naval battle of Lepanto on October 7, 1571, since this triumph was attributed to the intercession of Our Lady of the Rosary.35 This Madonna became the patron saint of the Spanish Armada, giving her a nickname of "La Galeona."

Similarly in Asia, an expedition to the Moluccas, carried out by Pedro Bravo de Acuña (d. 1606) in 1606 within the context of the rivalry between the Netherlands and Spain, ended successfully thanks to the intercession of Our Lady of the Rosary.36 This Madonna indeed became a protective mother of military enterprises organized by the Spanish Crown. The governor of the Philippines ordered an image of this Virgin Mary to be embroidered on the royal banner to guide the way. Moreover, a painting was executed on canvas representing the Virgin Mary and Child distributing rosaries to the governor, captains and soldiers.37

The devotion to the Holy Rosary became so important that other religious orders requested permission to spread it. Thus, this cult was no longer exclusive to the Dominicans. After all, there were not many differences in the most essential features of prayer. This devotion is also linked to the doctrine of the incarnation of the Word through the blessed Virgin Mary for the salvation of humanity.38 Hence, the Mother of God is worthy of all praise. Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), for instance, was a great devotee of the Virgin Mary and instituted the practice of "praying the Rosary to Our Lady, with the most cordial devotion" in his Exercitia spiritualia.39 The recitation of the Rosary was also prescribed in the Constitutions of the Society of Jesus.40

In addition to the propagation of the recitation of the entire rosary, the Order of Friars Minor developed its own short prayer form, known as "Franciscan Crown" or "Seraphic Rosary." This is a more simplified formula than Rupe's method of prayer. The number of mysteries is reduced further to seven to make them easier to memorize. This prayer form is based on the Corona Beatae Mariae Virginis (Corona B.M.V.), attributed to Saint Bonaventure (1221-1274).41 It centers on the recitation of prayers in honor of the Joys of the Virgin Mary, instead of three cycles (i.e. the joyful, sorrowful, and glorious mysteries) of the life of Christ.

Some of the first and most active promoters of this devotion were Bernardino of Siena (1380-1444) and his disciple John of Capistrano (1386-1456). The Hungarian Franciscan Pelbart of Temesvár (1435-1504), in his Stellarium Coro-nae benedicte Virginis Marie (1482), proposed contemplating the mysteries in relation to each of the seven parts of the Corona B.M.V. These were related to the seven joyful mysteries of the Virgin: the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Nativity, the Adoration of the Kings, the Presentation of Jesus at the temple, the Resurrection and the Coronation of the Virgin. This formula was followed by the Franciscan Mariano da Firenze (d. 1523) in his Tractatus corone beate Marie Virginis (1503).42 The order of prayer consists of reciting a rosary of seven decades of Hail Marys preceded by the Our Father, the Glory to the Father (Gloria Patri), the joy in turn, and at the end two Hail Marys are added to complete 72 years of Mary's life.43

Another cycle of Marian prayer widely promoted by the Franciscan Order is called stellarium, or crown of twelve stars. This prayer is linked to the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception.44 Regarding its origin, in his sermon in Dominica infra Octavam Assumptionis, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), Cistercian monk and mystic, identified the Virgin as the Woman of the Apocalypse, "who appears 'clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars' (Apocalypse 12:1) but who is also suffering the pangs of childbirth and is confronted by her enemy, the dragon who is the Devil."45 Saint Bernard also interpreted the twelve stars as symbols of Mary's twelve prerogatives. Later the twelve stars were associated with her twelve joys. These mystical interpretations favored the formation of the prayer cycle of the twelve Hail Marys to commemorate the crown of twelve stars. There is an anonymous work composed by a Franciscan friar at Montefalcone in 1474 and entitled the Corona di dodece stelle.46

As for the Crown of the Virgin of Consolation and Cincture, when establishing the Order of Saint Augustine in the I3th century, the Augustinians adopted the black leather cincture as a distinctive part of their habit. The faithful also were used to girding themselves with a belt in honor of the saints. To meet these devotional demands, two Augustinian brotherhoods were founded in the church of Saint James at Bologna. First, Pope Eugene IV (1431-1447) approved a Confraternity of the Cincture of St. Augustine and St. Monica in 1439.47 The devotion to the holy cincture increased markedly after the canonization of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino (1245-1305) in I446. Consequently, a Confraternity of Our Lady of Consolation was erected in 1495.48 In 1575 the Prior General of the Augustinian Order, Tadeo Guidelli, merged both brotherhoods into a single confraternity. This union was confirmed by Gregory XIII (1572-1585) in his Bull Ad ea (July 15, 1575). In the following year, this pontiff, who was from Bologna, raised the congregation, named the Holy Cincture of Our Lady of Consolation, to the rank of arch-confraternity.49 The members were obliged to wear a leather belt, and to pray daily thirteen Paternosters, Hail Marys, and the Salve Regina.50

Spread of the Rosary and Crowns in the overseas missions

There were two transmission routes of the Rosary before reaching Japan. One was the Portuguese sea route eastward to Asia and the other was the Spanish route, passing through Mexico and the Philippines. The former was the route taken by the Society of Jesus, which began to evangelize Asia, while the latter was the route of the mendicant missions. This section addresses the propagation and acceptance of the Rosary in New Spain as an antecedent of the mendicant missionary experience before arriving in Japan.

The Society of Jesus

The Catholic missions in Asia were undertaken by the Society of Jesus under Portuguese patronage. The devotion to the Holy Rosary was spread from the time of Francis Xavier (1506-1552). This saint always hung a large rosary from his neck. The first Japanese Jesuit Brother Lorenzo Ryosai (1526-1592), who supported Father Gaspar Vilela (1525-1572) around 1560, had a rosary in his hands.51 Similarly, Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries and Japanese Christians are depicted with a rosary in their hands in Nanban folding screens attributed to Kano Naizen (1570-1616) and now belonging to the Kobe City Museum (Fig. 1) and the National Museum of Ancient Art in Lisbon.52 Great fervor for blessed rosary beads, particularly among the Japanese was reported in different missionary sources. Wearing a rosary around the neck was regarded as "the greatest sign of being Christian."53

The brotherhoods were essential lay organizations aimed not only at promoting prayers and strengthening the faith, but also at maintaining the Christian faith without clergy in the context of persecution. Before Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598) issued an edict to expel Christian missionaries in 1587, the Irmandade da Misericórdia (Brotherhood of Mercy) and hospitals, which were engaged in charitable activities, were especially important within the Japanese Catholic community. Promoting the children's religious education was part of the work of the Brotherhood of Mercy in Bungo (current Oita). According to a letter from Juan Fernández, dated October 8, 1561, the children recited Christian doctrine in the catechism that took place after attending Sunday Mass. They prayed in Latin the Paternoster, the Hail Mary, the Creed and Salve Regina.54 The Jesuits also founded brotherhoods for children so that they could teach each other Christian doctrine. The confraternity of the Innocents, was established in Nagasaki, with the intention of teaching them prayers and to present a recital of crowns, thirds (praying a third of Christian doctrine instead of reciting it all at once) or rosaries to the Father Provincial once a year.55

Instead, after Hideyoshi's anti-Christian edict, missionary activities had to continue in private.56 The brotherhoods characterized by promoting internal religiosity and devotions such as the cult of the Virgin Mary and the Holy Rosary gained importance and became the basis of Japanese Christianity. To further Marian devotion, the first Sodality of Our Lady was set up for students by the Belgian Jesuit Jan Leunis (1532-1584) at the Collegio Romano in 1563; but later, several Marian congregations were also established in overseas missions. In Japan, the Jesuit Giovanni Battista Zola (1575/1576-1626) founded a Marian confraternity, called Santa Mariya no mikumi around 1595 in Arie, Shimabara after Nagasaki and Omura.57 Similarly, the activities of the Cofradia de Nossa Senhora (Confraternity of Our Lady) were recorded as an organization that resisted the persecution of Christians in Futae, Amakusa in 1596. The 1603-1604 annual reports on Jesuit missions in Japan inform that several "devotional-type" brotherhoods, such as Santissimo Sacramento (Blessed Sacrament), Nossa Senhora da Anunciada (Our Lady of the Annunciation), and "Compagnia di S. Michele" (Confraternity of St. Michael) were created in Nagasaki.58

The arrival of the movable-type printing press with the return of the Ten-sho embassy (i582-i590) to Japan together with the Father Visitor Alessandro Valignano (1539-1606) in 1590 played an essential role in the change of Kirishi-tan religiosity. Different manuals for devotional practices were translated into Japanese and printed by the Jesuit Mission Press using the Romanized characters or Japanese characters, as shown by the Doctrina Christan (Amakusa, 1592), book on the Catholic catechism, and Orasho no hon'yaku (Translation of prayers) (Nagasaki, 1600).

Several books written by the Dominican theologian Louis of Granada (1504-1588), with whom the Tensho Boys' embassy met in Lisbon in 1584,59 were published in Japanese: i.e. Fides no Doxi (Guide to the faith) (Amakusa, 1592), Guia do Pecador (Sinner's Guide) (Nagasaki, 1599), translation of Guía de pecadores (1556), Fides no Qvio (Guide to the faith) (Nagasaki, 1611), translation of Símbolo de la fe.60 Although Granada's Libro de la oración y meditación (Book of Prayer and Meditation) (1554) was not published in Japanese, the missionaries used it for evangelical works in Japan.61 Moreover, a manual of meditations, entitled Spiritual Xuguio (Spiritual Exercises) (Nagasaki, 1607) and printed with copperplate engravings, is a remarkable work of the Jesuit printing press in Japan to strengthen the devotion to the mysteries of the Rosary.

The books printed at the Jesuit printing press in Japan have greatly helped Christians, particularly in the time of persecution. According to a letter dated March 7th, 1623 and signed by twelve Jesuits in "Fingen" (Hizen), they did not prevent missionaries of other religious orders from establishing their confraternities of the Rosary, Cord and so on, and persuaded Japanese Christians to pray the Crown, or Rosary in honor of Our Lady. In order to inculcate in them devotion to the Virgin Mary, and to teach them how to meditate on the mysteries of the Holy Rosary and the life of Jesus Christ, the Society of Jesus printed a treatise on the fifteen mysteries in the Japanese language, and taught the people to pray the Crown and Rosary while meditating on their mysteries.62

Mendicant Orders

As mentioned before, the mendicant Orders were a second means for the introduction of the Rosary to Japan. Their overseas missions were carried out under Spanish patronage. In the Americas, the devotion of the Rosary was introduced by the Dominican Order. Even though this cult was a private practice among the friars in the beginning, they preached to the native people wearing a rosary around their neck, which coincides with the strategy used by the Jesuits in Japan. The rosary was regarded as a heavenly instrument given by the Virgin for conversion.63

The Franciscans also probably spread the Holy Rosary after obtaining permission from the Dominicans in New Spain. In this regard, Alonso Franco, a Dominican chronicler born in Mexico City at the end of 16th century,64 states that only the Order of Preachers could permit and commission to found a confraternity of the Rosary.65 The fact is that the use of rosary beads was widespread among indigenous peoples, as historical sources demonstrate. In his Historia eclesiástica indiana (written around 1595, first published in 1870), the Franciscan missionary Jerónimo de Mendieta (1525-1604) mentions that the Indians brought beads to pray, and then took them to a priest for blessing; "Among them, anyone who does not carry rosary and discipline (i.e. a scourge) seems to be a non-Christian."66 An almost identical statement was made by another chronicler Juan de Torquemada (c. 1557-1624) in his Monarquía indiana (Seville, 1615).67

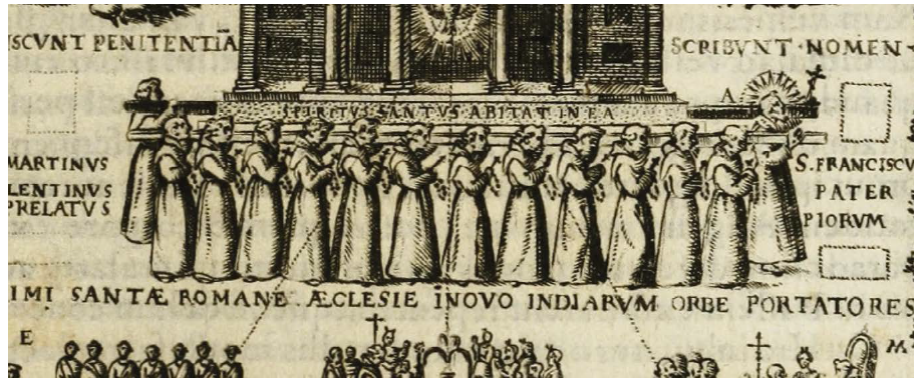

Furthermore, some visual images testify to the use of rosaries among the Franciscans of New Spain. In an engraving of the Rhetorica christiana (Perugia, 1579) by Diego de Valadés (1533-1582), the friars who carry a processional float in the atrium of the convent, have a rosary in their hands (Fig. 2). There is also a sixteenth century mural that depicts a penance procession of the Confraternity of the True Cross inside the convent church of Huejotzingo, Puebla, Mexico (Fig. 3).68 The flagellants who attend this procession carry a rosary in their hand and a cord tied around the waist. It is probable that both the Indians' beads described by Franciscan chroniclers and the rosaries depicted in the above-mentioned images are linked to the Franciscan Crown.69

2. Diego de Valadés, Rhetorica christiana (Perugia, 1579), detail of the illustration showing the activities carried out in the atrium of the Franciscan convent of New Spain.

3. The Penance Procession of the Confraternity of the True Cross, detail of a 16th century mural painting, Church of Saint Michael the Archangel, Huejotzingo, Puebla, Mexico. Archivo Fotográfico "Manuel Toussaint", IIE, UNAM. Secretaría de Cultura INAH-Méx. "Reproducción autorizada por el Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia".

In regard to the mendicant evangelization in Asia, the missionary enterprise in the Philippines began with the arrival of five Augustinians (Andrés de Urdaneta, Pedro de Gamboa, Diego de Herrera, Martín de Rada, and Andrés de Aguirre), who participated in López de Legazpi's trans-Pacific expedition and reached the archipelago in 1565.70 The discovery of the return sea route from the Philippines to New Spain in the same year made it possible to carry out trans-Pacific exchanges. Thus, other religious orders joined Catholic missions in the Philippine Islands: the Franciscans came in 1577, the Jesuits in i58i, the Dominicans in 1587, and the Recollects in 1606.

The Augustinian Order established the Confraternity of the Cincture in the Convent of Saint Augustine in Mexico in 1589.71 In the Province of the Most Sweet Name of Jesus of the Philippines, this congregation was created at the same time as their churches in Manila and Cebu, although this brotherhood could not be officially accredited until 1712.72

According to the i6th century Franciscan chronicler Marcelo de Ribadeneira, Asian converts had a high esteem for blessed beads, and prayed with them. Wearing a rosary around the neck became a popular custom for both men and women in the Philippines and Japan particularly.73 Diego Aduarte (1570-1636), Dominican chronicler and bishop of New Segovia in Luzon, informed of the spread of the Rosary confraternity in the Dominican Province of Our Lady of the Rosary from the initial stage of evangelization in the Philippines. Rosary brotherhoods were established in the towns through which the missionaries passed.74

To understand the acceptance of Catholic rosaries and blessed beads, preexisting local customs cannot be ignored. Besides the Jesuit sources, the mendicant authors describe in detail the use of blessed beads and strings of prayer beads in native religious practices and beliefs. Aduarte, for instance, states that the Filipino people "had beads tied around their wrists, such as blessed ones the sorceresses gave them, under threat of death if they took them off."75

In the Franciscan missions in Japan, Gerónimo de Jesús, devotee of the Rosary,76 founded the church of Our Lady of the Rosary in Edo (present-day Tokyo) on May 30, 1599. This church existed until 1612.77 A brotherhood of the Rosary was established with permission of the Father Provincial of the Dominican Order in Manila, although the confreres were not informed about the indulgences of the Rosary.78

The Seraphic Order promoted the prayer of the rosary or crown in their missions. The devotion to the Rosary among them is also noted in Japanese pictorial sources. In the Nanban folding screen by Kano Naizen in Kobe (Fig. 1), a Franciscan friar is portrayed with a rosary in his hand. It is also noteworthy that a Franciscan friar is represented under the flag with rose motif in the Nanban folding screen attributed to the same painter and belonging to the National Museum of Ancient Art in Lisbon (Figs. 4-5).79

4. Kano Naizen, Nanban screen, 1593-1601, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Photo: Luísa Oliveira/José Paulo Ruas. © Direção Geral do Património Cultural /Arquivo e Documentação Fotográfica.

5. Kano Naizen, Nanban screen, detail, 1593-1601. Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. Photo: Luísa Oliveira/José Paulo Ruas, © Direção Geral do Património Cultural /Arquivo e Documentação Fotográfica.

Furthermore, The Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary with Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Anthony of Padua and Saint John the Baptist is a Franciscan painting created by a local painter. This work was preserved among the Kakure Kirishitan (hidden Chiristians) in Sotome, Nagasaki. This painting was found in 1865 by Bernard Petitjean (1829-1884), a French missionary who arrived in Japan in 1862 and the first bishop of Oura Cathedral, Nagasaki. When this father found this work in Sotome, he recorded that it was a painting representing the fifteen mysteries with Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Anthony of Padua below without specifying the third figure (Saint John the Baptist) due to its deterioration.80 Later, this painting became a collection of the Urakami Cathedral in the same city, but it was lost due to the atomic bomb on August 1945.81

The Virgin of the Rosary with the Christ Child and Four Holy Hermits (Fig. 6) now belonging to the Sendai City Museum is an oil painting brought to Japan by Hasekura Tsunenaga (1571-1622), who led a diplomatic mission to Spain and the Vatican, traveling via New Spain, between 1613 and 1620. This work is linked to the Franciscan rosary because the founder of the Seraphic Order appears as one of the four holy hermits in the lower part of the painting.

6. The Virgin of the Rosary with the Christ Child and Four Holy Hermits, oil painting on metal plate, early 17th century. © Sendai City Museum.

This painting dates from the early seventeenth century, but its provenance is not known exactly. Based on the type of production, Tei Nishimura supposed that Hasekura could have obtained this work in New Spain.82 A few decades later, Keizo Kanki also supposed it to have been a Hispano-American work, most likely Mexican.83 However, after finding an ivory piece with the same composition made by a Sangley in the Philippines in the collection of the Toledo Cathedral (Fig. 7), Kanki reconsidered his previous postulate, and stated its possible Filipino provenance. Since it is a small format painting on brass plate (30.2 χ 24.2 cm), he also considered that it must have been an object of personal devotion, besides being a work produced for export.84 However, there is no consensus among researchers on its place of production. Thus, the painting has been catalogued as a Spanish-America work in the Catalogue Raisonné of Namban Art, coordinated by Mitsuru Sakamoto,85 while Kazuhiro Sasaki supports Kanki's statements.86

7. Triptych The Virgin of the Rosary with the Christ Child and Saints, ivory relief made in the Philippines by a Sangley craftsman, early 17th century, © Cabildo Catedral Primada de Toledo.

In the center of the composition, the Virgin is depicted crowned and standing on a crescent, holding the Child with her right arm and a rosary in her left hand. The Child is also holding a rosary in his hand. These main figures are surrounded by a large elliptical rosary. But unlike the Toledo ivory piece, ten roses are added to it.

Emphasis is made on the Rosary as a tool for meditative exercise through the representation of holy hermits. On the left side, Saint Jerome is represented with a lion, and Saint Anthony the hermit (Saint Anthony the Abbot) together with a pig, which symbolizes the temptations of the saint. On the right side, Saint Francis of Assisi is depicted with his stigmata in his hands, while a kneeling anchorite represented behind Saint Francis has been identified variously. He has been regarded as Saint John the Baptist for being depicted half naked and holding a stick.87 But, Keizo Kanki identifies him as Saint Onuphrius (c. 320-400), since he has a crown on the ground.88 This saint lived as a hermit in the Egyptian desert in the 4th century. His iconography is characterized by his dress with leaves, a scepter and a crown at his feet, symbolizing the resignation of his royal lineage.

Concerning the Franciscan ascetic and eremitical tradition, the active and contemplative lives are two attitudes which have been developed within Christian spirituality. Both are linked to the salvation of the human being, but through different methods. As for the mendicant orders, their preaching campaigns are often emphasized in contrast to the monastic orders. However, Franciscan asceticism and contemplative exercises date back to the time of Francis of Assisi. Eremitical practice among Francis and his followers has been studied by several authors.89 The Regula pro eremitoriis data (Rule for hermitages) by Francis of Assisi shows the importance of balance in active and contemplative lives. The Franciscan community does not profess to lead an exclusively contemplative-eremitic life, even during the period of spiritual training in the hermitage.

With regard to eremitical practices among Franciscans in New Spain, Martín de Valencia (c. 1474-1534), leader of the "Twelve" missionaries who undertook evangelical work in Mexico in i524, had been in the Convent of Saint Onuphrius in La Lapa, Extremadura.90 This was one of the major eremitical centers of the time. The guardian of this convent, St. Peter of Alcántara (1499-1562), composed his Tratado de la oración y meditación (Treatise on Prayer and Meditation), a key contemplative work of Spanish mysticism. The "Twelve" referred to above had to dedicate themselves to active life due to the demand for evangelical works. However, Martín de Valencia made his retreat in Sacromonte, near Mexico City at the end of his life. Moreover, there was an eremitic tendency among the Franciscans who arrived in New Spain in the middle of the i6th century.91 It would be a task for the future to delve into eremitical practices among the Franciscans in New Spain and the Philippines so as to contextualize the production of the painting belonging to the Sendai City Museum.

In the case of the Augustinian Order, Hernando Ayala, or de San José (d. 1617) founded the Confraternity of the Cincture for both males and females in the Convent of Saint Augustine in Nagasaki. The number of confreres grew in a short time. They gathered in the church with great devotion to practice spiritual exercises.92 Hernando's devotion to the Rosary is recorded in the moments before his martyrdom. That is, after receiving his death sentence, Hernando sent the cincture to the brotherhood of men of Saint Augustine in Nagasaki, asking not to distribute it among the confreres, but to give it to the steward. Similarly, he sent the beads to the female congregation giving the same instruction. At the moment of martyrdom, he had a rosary in one hand and a lighted candle in the other.93

In regard to the Order of Preachers, the missionaries dedicated their churches to the Virgin of the Rosary in Japan; such were the cases of Koshiki in Satsuma, Hamamachi in Hizen, Kurume and Kyoto.94 Francisco Morales (1567-1622) founded the confraternity of the Rosary in Nagasaki in 1604. According to him, "a few days after, more than twenty thousand confreres were enrolled in the book of this holy brotherhood."95 Jacinto Orfanell (1578-1622) states that, although the brotherhood of the Rosary was already established in Nagasaki throughout the time the churches existed, the devotion to the Rosary did not gain as much vitality as it did after the arrival of the Dominicans.96

Another existing Dominican brotherhood in Japan was called the Sweet Name of Jesus. This confraternity was originally founded by Diego de Victoria in the Convent of Saint Paul, Burgos, and approved by Pius IV on April 13, 1564. There are two theories concerning its origin in Japan: i) the Japanese priest Francisco Antonio, son of Murayama Toan (d. 1619), magistrate of the city of Nagasaki, established the above-mentioned brotherhood in i6i4 with support from the Dominican Alonso Navarrete (1578-1622).97 This confraternity was also called "Confraternity of the Cross"; 2) Navarrete organized the congregation in question in 1616.98

There were two types of members in the confraternity of the Rosary: "ordinary" and "numerary." The numerary members of the Rosary brotherhoods were the same persons as those of the confraternity of the Sweet Name of Jesus.99 Thanks to its effective organization, the Rosary movement gained great strength from 1616. "The Rosary brotherhood is distributed in many streets in this way. In each street there is a male steward for men, and a female steward for women, whose job is to make them pray, get together when they read a book of devotion, etc."100 The enthusiastic activities of the confreres lasted until 1619.101

The devotion grew so much that several images of the Rosary were painted, and it was even necessary to print the image because this devotion was not confined to the city of Nagasaki, but also spread to other parts.102 In particular, paintings and engravings after drawings by Alonso Navarrete helped foster this cult. The Dominican Juan de los Ángeles Rueda, who joined the mission in Japan in 1604, states that everyone was very aware of the importance of the devotion and Confraternity of the Rosary. More than fifteen hundred images of the Rosary had been painted. There were no lands where the Confraternity of the Rosary was better established than in Japan.103 Rueda also describes in detail Navarrete's work depicting the Madonna and Child distributing rosaries:

There are many confraternities that have been founded, and the images of the Rosary that have been painted [...] very large with all the 15 mysteries, and the Mystery painted within a large red rose, and a large Rosary with some angels around all the Mysteries of the Rosary. The Mysteries placed in a rose bush, the root and foot of the rose is put into a jar, a very beautiful glass, in the way that flowers are placed in glasses on the altars. There together, on one side, the Pope, cardinals and bishops, and monks of various orders are painted; and on the other side, next to that glass of the Rosary, the emperor of Rome, and Kings and noble people are painted. And all the above mentioned, with Rosary in their hands adoring the Virgin of the Rosary. Over 100 images of the Rosary have been painted in Nagasaki alone, and many images have been painted for other realms, and every day so many [images] are commissioned to three or four existing painters in Japan, who lack sufficient hands to paint with. Therefore, they always have more than enough images and commissions they cannot finish.104

This record is very valuable, since no painting produced by the Dominican Order in Japan is currently preserved. It is also worth mentioning another contribution by Rueda. He encouraged the Japanese to pray the Rosary not only with words but also by publishing two books in Manila in the Japanese language: Rozariyo kiroku ろざりよ記録 (Memorials of the Rosary) (1622) and Rozario no kyoろざりよの經 (Sutra of the Rosary) (1623).105

Intersection between Buddhist and Catholic prayer traditions

To answer the questions posed at the beginning of this paper, it is necessary to analyze the acceptance of Catholic rosaries, taking into account native religious traditions. The first references to Japanese Buddhist beliefs and practic es appear in the informative documents the Society of Jesus prepared at the request of Francis Xavier before undertaking the mission in that country. On the one hand, the Portuguese captain Jorge Álvarez (d. 1521) reports diverse uses of Buddhist "contas" (beads) in a letter sent to Francis Xavier around 1546-1547:

There are a people very devoted to their idols. In the morning everyone gets up with the beads in their hands and prays, and after finishing praying, they take the beads between their fingers and rub them three times. And they say they ask God to provide them with health and temporary well-being and to free them from their enemies. This [is practiced] in their houses, in front of the idols that they have there.106

Here it is noteworthy that praying using a Buddhist string of beads was linked to a popular belief in receiving benefits in this world such as health and temporary well-being. Precisely, this was one of the confluent points between Buddhist and Kirishitan beliefs. The Japanese converts believed in the supernatural power of the blessed beads, such as the effectiveness of the indulgences earned by recitation.107

Similarly, Álvarez describes mountain hermits, called yamabushi, of Shugendõ, a syncretic religion composed of elements taken from mountain worship, the Tendai sect, Taoism, and Shintoism. These ascetics "are great sorcerers and always wear beads around their necks."108 Here the terms "humas contas" do not refer to prayer beads, but a Buddhist stole with six tassels, called yuigesa. "The yuigesa is a surplice or vest with six brass or pompom like tassels (kesa). Normally worn with four showing on the front and two on the back, they represent Vairocana's six forms of protection."109 Wearing this stole means protecting them from misfortunes during their training."110 The string of i08 prayer beads the yamabushi carry is known as irataka nenju. Unlike other sects, these mountain ascetics make a sound with beads when praying and lecturing on the sutras to exorcise evil spirits.111 It is noteworthy that Fróis points out that for Japanese Christians, hanging a Catholic blessed bead from the neck served as protection to chase away scare the devil.112

Nicolao Lancillotto, rector of the College of Saint Paul in Goa, collected information about Japan through the interviews with Anjirō (c. 1511-1550), a Japanese man who received Catholic instruction at that college. This source describes the Buddhist method of prayer as follows: "They say one word for each number because according to them, there are eight hundred things in man which are offensive for God."113 This document erroneously reports that Buddhist prayer beads consist of "ottocento'" (eight hundred) beads.114 This error seems to have led to confusion among other writers. Francis Xavier, for instance -in his letter sent from Cochinchina on January 29, 1552- states that a set consisted of "more than one hundred and eighty" beads.115 The correct amount of the entire string of beads is 108, while its variants have half (54), a quarter (27), and a sixth (18), respectively. Xavier also informs regarding the method of praying: they recite the names of the founders of their sects, the two most important being Shaka and Amida.116

In his letter sent from Cochin on January 29, 1552, Francis Xavier states that the Japanese stopped praying Buddhist prayers as soon as they became Catholics. Everyone first learned to make the sign of the cross on their forehead."117 After praying in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, the converts recited the Kirie eleison (Lord, have mercy), and "Then they pass their beads, saying Jesus, Mary to each bead. They are slowly learning in writing Our Father, Hail Mary and the Creed."118

Nonetheless, Luís Fróis (1532-1597), in his Historia de Japam, testifies to the coexistence or simultaneous use of Buddhist and Catholic strings of beads and prayers among converts. Thus, in 1562, in the province of Kawachi,

There was an honorable man there; an old, simple and naturally good man, and very desirous of salvation, who had received baptism together with another 73 a few days before. It was very cold, and he walked on a terrace in front of this new church, praying with some beads [he had from] when he was a gentile, for which nothing more was required than to run them through the hand, saying: «Namu Amidabut», and they are like two half rosaries, one chained within the other. The priest chanced to see him, and asked him, astonished: «So-and-so, are you not a Christian?» - «Father, yes, I am» (the old man responds). - «Where are your Christian beads?». «Here (he says) I have them on my belt». - «And these ones you have in your hand, why do you pray with them?» - The old man replied: «Father, I have been a great sinner until now, and I pray with the Christian beads and ask Our Lord to have mercy on my soul; but, as I heard in the preaching, He is also very unswerving and rigorous in justice. So if at my death it should be that my sins are so many that God [might think me] unworthy to be admitted to his glory, I also pray with the se beads to Amida, begging him to take me to his paradise which I call Gocuracu."119

In this regard, Ikuo Higashibaba notes that besides the coexistence of juzu (Buddhist prayer beads) and rosary, it is interesting that the old man also prays to Amida Buddha thinking on the possibility of God failing to grant him salvation after death. In his belief, not only the deities of different religions (i.e. God and Amida) coexist, but the cult of Amida Buddha functions as a backing for the belief in God -a "religious insurance system." Kirishitan beliefs are distinguished by mixing elements derived from different religions. This is a characteristic of the religions of Japan.120

The continuity between juzu and rosary is also observed from both material and formal points of view. Fróis states on August 20, 1576, that Takayama Dario (Takayama Tomoteru, d. 1595), the daimyo (lord) of Settsu, invited a woodturner from Kyoto to make rosaries for Christians and later managed to convert him to Catholicism.121 Rosary beads found in the Takatsuki Castle of the Takayama clan, have the same shape as Buddhist prayer beads. In Japan, glass beads were very special and rosary beads were usually made of wood. There were also rosaries without separating beads just like the juzu. It is possible that distributing these Japanized rosaries was an attempt by the Society of Jesus and the Kirishitan daimyo Takayama to facilitate the acceptance of the Catholic rosary among converts.122

Similarly, the Franciscan chronicler Ribadeneira provides information on the main sects of Japan. He points out that the ways of worshiping idols are very different depending on the sect. But the common practice is the repeated invocation of the name of Amida Buddha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, as mentioned below:

[they] have idols in their temples, and carry long rosaries, hanging on the neck or in the hands, because with them they pray their vocal prayers, which is only saying Amidabut. How many times do they say this word (that means Holy Amida), and leave aside so many beads of their rosary. [...] And when the infidels go to the temple of their sect or any other, their way of worship and reverence is to link the beads between the fingers and rub them hard between the hands in front of the idols.123

With regard to the "sect of Amida," Ribadeneira states: the followers of the Xaca sect ridicule it "mocking those who seek salvation by uttering words, carrying beads in the hands, because salvation is nothing else but a quietness of soul within the body, which is achieved by spending a long time without thinking about anything, and hell [...] is to live with a restless imagination, and the heart afflicted with cares."124 Ultimately, this statement shows that prayer has a universal purpose of salvation regardless of religious differences.

Ribadeneira indicates "And it is easy to persuade because if the Christians say they carry a rosary to pray, the Gentiles also say that we carry rosaries for the same propose, but they do not heed the difference that exists between one kind of prayer and another."125 This testimony suggests a continuous practice of Buddhist prayers among Japanese converts not only in the initial stage of evangelization, but probably during the century following the arrival of the Catholic mission in Japan.

Furthermore, the intersections between Catholicism and the True Pure Land School (Jõdo-Shinshü) also occurred in the doctrinal field. Thus, in the Japanese translation of Guia do Pecador ぎやどぺかどる (Sinner's Guide) by Louis of Granada, published by the Jesuit printing press in Nagasaki in 1599, Catholic dogmatic concepts were translated using the terms of True Pure Land Buddhism. The theory of indulgences is explained here with the Buddhist term "hōsha 報謝 which shows infinite gratitude for Amida's salvation. Human beings must cultivate their virtues in response to the benefits that God offers us.126

Conclusions

This work has addressed the parallels concerning the strings of beads used by different religions. The blessed beads enjoyed particular esteem as they were believed to possess a certain kind of mana, supernatural power that inheres in animate being or things. Beads were used for both purposes: for spiritual protection and as a prayer tool.

Prayer beads are often considered to have their origin in India due to the antiquity of the known sources. But their precise origins are actually unclear. Rather than determining a single origin, it is also possible to consider mutual influences between different religions or cultural parallels. At least the Buddhist strings of beads has its antecedent in Hindu ones. Therefore, the Buddhist full string is composed of 108 beads, like the one used for the worship of Vishnu.

Regarding the Catholic custom of praying the Rosary, different religious orders developed their own prayer traditions, aside from the recitation of an entire Rosary as promoted by the Dominicans. Thus, the Order of Friars Minor has its own short prayer form, known as "Franciscan Crown" or "Seraphic Rosary," as well as stellarium, or crown of twelve stars. The Order of the Hermits of Saint Augustine promoted a Marian prayer known as the Crown of the Virgin of Consolation and Cincture. The Society of Jesus prescribed the recitation of the Holy Rosary in its constitutions and Loyola's meditation book Exercitia spiritualia.

How did the Japanese converts accept the Catholic rosary and blessed beads? To what extent was the conversion of Japanese people thorough? Several chroniclers state the deep devotion that the Japanese had towards the blessed beads. Common points between Buddhist juzu and Catholic rosary consisted in materials, forms and beliefs. On the one hand, most of the rosaries used by the Kirishitan were made of wood. The beads had the same shapes as those of the juzu, as shown by archaeological remains. This analogy could be part of the strategy of the Society of Jesus to facilitate acceptance of Catholic rosaries among the Japanese people.

On the other hand, both Buddhist and Catholic beads and prayers were linked to the popular belief in the benefits to be received in this world, such as health and temporary well-being. In both religions, wearing blessed beads around the neck served as protection to chase away evil spirits. Moreover, prayer has a universal purpose of salvation regardless of religious differences. Interestingly, in the case of Japan, there was an "addition" in the Kirishitan beliefs. The Buddhist and Catholic beads and prayers coexisted among ordinary people. The Catholic doctrine of indulgences was understood through the concepts of True Pure Land Buddhism.

The level of conversion varied according to the social status of each believer. The religiosity of the Kirishitan daimyo (lords) was not the same as that of the converts from lower classes. However, the latter's religious practices and beliefs cannot be simply regarded as "heresy," taking into account the number of martyrs among ordinary people. Ultimately, Kirishitan beliefs are at the intersection of elements derived from different religions. Consequently, they are particular to Japan.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)