Francis in the Sky: a New Look at a Beloved Saint

“A meta-narrative about the future of the human race as it was understood in the early modern world of the Americas,” is how Jaime Lara introduces on page one the main topic of Birdman of Assisi: Art and the Apocalyptic in the Colonial Andes1 and Lara concludes his book, “My intention first and foremost has been to write a work of art history” (256). Between the covers Lara has accomplished both objectives; but Birdman is far more. Lara reveals how St. Francis becomes the Birdman of Assisi in fascinating detail along with more than two hundred gorgeous color plates and photographs of etchings, woodblock prints, mosaics, murals, oil paintings and finally Andean processional winged sculptures.

Hagiography

The life of St. Francis (né Giovanni Francesco de Bernardone c. 1181-1226) was one of contradictions: luxury/poverty, insouciance/troubled self-examination, solitude/outgoing charity, hedonism/Christian devotion, gentleness/strictness and above all mystic influence. Francis envisioned living as Jesus did -an itinerant life dependent on the good will of strangers as he wandered his world, and even the Saracen world, bringing Christ’s message to all he met. Born in Italy, in the small town of Assisi, Francis’s legend spread throughout the Christian world. His Order, the Franciscans Minor, approved by Pope Innocent III in 1209, was the first to bring the Christian faith to the Americas three centuries later, and the saint remains to this day the inspiration for countless books and for art in all media.

The entire life and history of St. Francis are products of the era in which he lived: the Middle Ages, and all that we read and see has to be filtered through that historical scrim. Religion during Francis’s life meant the Roman Catholic Church. And the Church, with supremacy as great as the crowned heads of Europe, meant wealth and power for its pope and high officials. Until the Reformation, no one questioned the Church. Brilliantly, Lara presents the eschatological-driven age into which Francis was born as the crux for understanding the development of Francis the winged icon. Integral to Francis’s story, Lara, early on in Birdman, devotes a large section to the visionary writer and near contemporary of Francis, Joachim de Fiore (1135-1202), a priest and a monk who, being well-known in the Middle Ages, appears in Dante’s Paradiso: “at my side there shines Calabria’s abbot, Joachim, endow’d with soul prophetic.”2 When it was necessary in 1245 to prevent the destruction of the writings of Joachim de Fiore where they were kept in his monastery at San Giovanni, Joachim’s manuscripts were brought to Pisa and placed in the hands of a group of Franciscan friars there “from this time on, many in the [Franciscan] Minorite Order dedicated themselves to the study of [these] texts. Those in favor of the most rigorous observance of poverty within the Franciscan family began to make use of the Joachite apocalyptic to further their cause” (22). Because Lara probes in great depth the connection of Francis with the writings of Joachim de Fiore, his impressive tome is perhaps the definitive work on the impact of St. Francis, in early religious history, and Lara’s erudition and flowing style create a riveting narrative.

Joachim’s exegesis of the biblical book Revelation, presaged the imminent end of the world. His predictions also appeared to foretell the coming of St. Francis and St. Dominic who, according to Joachim, would convert all who remain on earth to Christianity and issue in a New Jerusalem. True to Joachim’s vision, the proselytizing orders, Franciscans and Dominicans, were both founded in the 13th century. We are told that Dominic and Francis met each other only one time, cordially, an event that was a favorite subject in paintings by Fra Angelico, and others in the early Italian Renaissance and beyond.

Nevertheless, in later centuries their orders would become rivals, particularly around the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, another topic Lara explores in depth. With a whiff of humor, Lara notes that in Arequipa, Peru the ritual of the Holy Encounter of Saints Francis and Dominic continues to this day […] The images are borne on ornate litters from their respective churches to the rendezvous in the public plaza. There they are made to embrace one another and offer a fraternal kiss during which they supposedly whisper celestial secrets that only a saint could know (188).

It was a member of the Order of Franciscans Minor, Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, who in 1263 was chosen by the Brothers to write a legenda of the life of Francis. “With almost blasphemous literary license,” Lara notes, “Bonaventure substitutes the Poverello [Francis’s nickname] for Christ ‘The grace of God our savior has appeared in these last days in his servant Francis’ ” (18-19). Rapidly, Francis evolved, as Joachim foresaw, into the alter-Christus, he who is a second coming of Christ.

In Lara’s book, we see Francis as a newborn in a painting from the 1700’s entitled Nativity of Saint Francis. The complex iconography in the painting contains a host of notables including Joachim de Fiore, Old Testament scribes, a pre-Christian sibylline, Franciscan friars, and, in a later version of the same scene, the archangel Rafael who tattoos Francis’s chest with a crimson cross -surely one of the earliest tattoos on a person of European extraction. Other mind-boggling symbols from the book of Revelation in the painting include a bleeding moon and a blackened sun, a roiling sea and a dragon. Francis’s well-off parents are dressed in the finery of the eighteenth century, and, as if the message of St. Francis as the alter-Christus weren’t clear enough, the artist has placed the scene in a stable and the baby Francis in a manger (9).

Another birth scene, painted by Basilio Pacheco de Santa Cruz Pumacallao (1635-1710), a Quechua painter from Cuzco, depicts the newborn St. Francis in the arms of a typical South American archangel. Richly dressed midwifes attend the mother who lies in a canopied bed under which is a fine oriental rug. In the background, again suggestive of St. Francis as the alter-Christus, is a scene of baby Jesus in a manger with animals in the stable looking on.

Biography

In 1202, as a young soldier of Assisi’s local cavalry, Francis, dressed in chain mail, fought in the war against Perugia. The battle between the warring city-states did not go well, and Francis was captured and made a prisoner for nearly a year.

Francis was deprived of his horse, stripped of his arms and marched by the light of torches up through the gates of Perugia. Herded through the streets between jeering crowds, the prisoners had no idea if they were heading for execution or torture. The dungeons into which they were finally thrown were part of the city’s Etruscan foundations -cold, dark, damp, and soon stinking. For the first time Francis, the spoiled young man, with his troubadour dreams of love and knighthood, had collided with the uglier realities of medieval life.3

After his release from prison, Francis, looking for some meaning in his life beyond the sports and games of the knights and playboys of his age, came upon a leper and was suddenly moved to give him his own cloak. His well-known conversion from bon vivant to servant of Christ had begun. Shortly afterwards Francis heard himself addressed by a voice as he was praying in the run-down chapel of San Damiano in the hills above Assisi. The voice which was coming from a 12th century Syrian-style painted crucifix told Francis to repair the old church (9). In astonishment but with enthusiasm, Francis set about to do just that. However, in order to afford building materials, he stole and sold bolts of expensive French cloth that belonged to his textile-merchant father. As might be expected, his father disinherited him and, after locking him in a storage room, dragged him before the Bishop of Assisi and insisted Francis repay him for the cloth he had taken, whereupon Francis returned what cloth and coins remained and, stripping off all his clothes, gave them to his father as well. Shocked but sympathetic, the bishop “stepped to Francis and covered his nakedness with his ample cloak” and sent him away.4

G.K. Chesterton opines with insight:

It is possible that after his humiliating return from his frustrated military campaign he was called a coward. It is certain that after his quarrel with his father about the bales of cloth he was called a thief. And even those who had sympathized most with him […] had evidently treated him with an almost humorous amiability which left only too clear the ultimate conclusion of the matter. He had made a fool of himself.5

Lara picks up the story of Francis’s conversion:

The action marked a decisive point in his turn toward radical poverty as a means and as a goal, and it would mark all his actions for the rest of his life. Now Francis set off wandering in the hills around Assisi, improvising hymns of praise as he went. [During a mass one morning in 1208], the Gospel of the day told how a disciple of Christ was to possess neither gold nor silver, nor two coats, nor shoes, nor a staff for his journey […] This passage lit Francis’s path and later became the rule for a loosely bound community of [his fraternity of friars] (9).

Francis as alter-Christus

Critical to understanding Francis, his legend, and his appearance as a religious icon is the mystery of the stigmata. In August 1224, two years before his death, lame and nearly blind, Francis ascended to a mountain retreat on Mont Alverna with three friends for a forty day period of prayer and fasting in preparation for Michaelmas, the celebration of Lucifer’s expulsion into Hell by the Archangel Michael. Here Francis experienced a miracle.

“It was on or about the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, while praying on the mountainside, that Francis beheld the vision of a flying crucified seraph and watched as there appeared on his own body the visible marks of the five wounds of Christ” (10).

Artists for centuries have envisioned and depicted this miracle, this anointing with Christ’s wounds. In churches, monasteries, and convents around the world, printed and painted images of the sackcloth clad, tonsured St. Francis, bleeding with the marks of the stigmata on his hands and feet and the single wound on his right side are greatly venerated. Lara writes:

Brother Leo, who claimed to have been with Francis when he received the stigmata, has left us a clear and simple account of the miracle that transfigured Francis into an alter-Christus, another Christ. In Leo’s stunned eyes, Francis’s right side bore an open wound that appeared to have been made with a lance. Driven through his hands and feet were black nails of flesh, the points of which were bent backward (11).

At the Philadelphia Museum of Art a tiny painting by 15th century Dutch painter Jan Van Eyck depicts St. Francis receiving the stigmata. So fine are the details of men in a boat on the sea in the background of the painting that a magnifying glass is provided to visitors in order for them to marvel at Van Eyck’s mastery of his brush. Francis, kneeling, stares off into the distance at what we know not. He evinces no pain, yet his feet and hands clearly show the wounds of the crucifixion. In front of Francis, Brother Leo is asleep in a sitting position, completely unaware of the transformation occurring behind him.

Of particular interest here is the seraph. In the background, while not iconographically unique, the figure is not the typical fiery angelic seraph hovering in the sky but a cross with the clear INRI (Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews) taunt on which hangs Christ, bleeding from his side, who is himself the seraph with four seraphic, colorful wings like those seen on archangels in South American art.

Already broken by continual mortification, Francis suffered increasing weakness throughout his frail body following his stigmatization. Chief among Francis’s ailments was pain and blindness in his eyes. Horror stories of medical treatments in the Middle Ages abound, and, not unexpectedly, the treatment for the severe pain Francis had been experiencing in his eyes for several years “entailed cauterizing the veins in his temples to stem the flow of tears and pus […] In a tall bare room upstairs Leo and the others waited with him while the brazier was lit and Master Nicholas plunged his branding irons into its heart until they grew red hot.6

So that he wouldn’t be too frightened Francis said to the fire: “My brother, noble and useful among all other creatures as you are, be courteous to me in this hour for I have always loved you and still do. I beg our Creator, who made you, to temper your heat so that I can bear it.” As for us who were with him, we all fled out of love and pity; only the doctor remained.7

It would be two years more before St. Francis died. When it was clear to him that his life was at an end, Francis had his Brothers carry him to the Portiuncula, St. Mary of the Angels, another of the beloved chapels for which restoration he had collected alms. The date of his death was October 3, 1226. Only at his death was his stigmata revealed to the world.

Taking off his shift they laid his naked and emaciated body as the last expression of his vows of poverty and humility on the bare ground […] Then they washed him [and] anointed him with spice […] Candles and incense were lit around his bed. Francis had taken the greatest care to ensure that [his stigmata wounds], which had never fully healed since their appearance two years before, should be kept secret except to the very few who looked after him.8

Although his last years were physical agony, it is the persona of the joyful man at peace with himself and his God that persists.

There was about Francis a chivalry and a poetry that gave to his other-worldliness a quite romantic charm and beauty and put him thoroughly in touch with the spirit of the age. He delighted in singing the songs of the French troubadours, in tearful public speech, in play-acting, and in comedy […] This exquisitely human element in Francis’s character was the key to that far-reaching, all-embracing sympathy for human beings, as well as for flora and fauna, that may be called his characteristic gift (11).

On the other hand, Francis could be harsh. In his own writings, Francis took care to leave instructions for the very strict rules of his Order. They carefully lay out what is entailed for a brother to accept and keep to the Order’s vows of Poverty, Chastity, Humility, Obedience to God, Prayer, Work, Harmony, and Preaching. In a letter to all the friars, Francis wrote:

I also beg my brothers who are priests […] whenever they desire to celebrate Mass, they should offer the true sacrifice of the Body and Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ with purity and reverence, with a holy and blameless intention […] If anyone acts otherwise, he becomes like Judas the traitor and will answer for the body and blood of the Lord!9

Jon M. Sweeny, who compiled Francis’s own writings, cites I Corinthians 11:28-29 as the closest Biblical source for Francis’s admonition above, but the passage in the Bible is far less harsh and does not make the miscreant responsible for the betrayal of Judas that led to the death of Jesus upon the cross. Again, Sweeny quotes Francis who goes on to remind his Brothers to take Mass once each day and to observe this Rule with “purity of heart.” With asperity, Francis says, “Whoever does not observe these rules I consider neither a Catholic nor my brother, and I don’t wish to see them or speak with them until they have done penance.”10 Needless to say, the sometimes saccharine image of Francis does not always ring true. In art also, Francis has a vengeful side.

Three paintings reproduced in Birdman show St. Francis, the alter-Christus, with sword in motion, stabbing the Anti-Christ in the chest. The most delightful depiction of vengeance is the story behind paintings on the pages of Birdman in chapter six entitled “Francis and the Headless Bishop” from a seventeenth century tale:

In the church of a bishop who persecuted the Order of the [Franciscan] Minorites there was an image of Saint Paul with a sword in his hand and another [image] of our father Saint Francis holding a cross. One night the sacristan heard the image of Saint Paul speaking and offering Saint Francis his sword [a scimitar] so that he could take the life of that bishop, the persecutor of his Order. In the morning they found the emblems of the saints [in the paintings] interchanged: Saint Paul with the cross in hand and Saint Francis with the bloody sword; and the Bishop awoke beheaded (209).

Revisionist art

In the early Renaissance in Italy, artists Cimabue, Giotto and others depicted a clean-shaven St. Francis. By the seventeenth century, Spanish artists Zurbarán and El Greco, Caravaggio in Italy and the 17th century Cuzco artist Diego Quispe Tito had added a beard to his visage (fig. 4).

Francis’s rough brown robe tied at the waist with a rope is nearly constant in Europe except that through the centuries it becomes a richer, cleaner fabric that falls gracefully and is from time to time a grey-blue color. However, St. Francis in Latin America is at times regally depicted in a robe embroidered with gold or lace as if the saint had sequestered bolts of his father’s cloth (fig. 5).

Franciscan friars, who were the first religious to arrive in the New World, brought with them Flemish and Italian prints as aids in evangelizing the native population. In her discussion about originality in the art of New Spain and South America, Clara Bargellini identifies details from the prints and also paintings copied by natives and New World Spaniards who added their own creative variations.11 Clearly the unique Andean adaptation consisting in putting wings on St. Francis was a creative invention inspired by the winged gods of the Andean natives and the abundance of colorful native birds. Bargellini reminds us also that religious paintings are iconographically determined according to the saint or deity depicted and therefore repetitive despite the originality of the painter. St. Francis is known by his contemplation of a skull and/or his stigmata even when not in his typical brown robe of rough cloth tied with rope.

Francis and the Birds

How St. Francis became Birdman, or the evolution of St. Francis in the sky, begins with his ascendency in medieval times as a figure on early monumental Byzantine mosaic ceilings and interior dome paintings high above any viewers’ heads. As always, he is identifiable by his sack-cloth robe tied at the waist with a knotted rope and the stigmata on his body. In works of art, Francis keeps august company. We see him with God and Christ; with the Virgin Mary; with burning seraphim, angels and archangels; with bishops, priests, nuns, prophets, and fellow mendicants. Best known are stories and paintings of Francis preaching to the animals, especially the birds (fig. 6).

My brother birds, you should greatly praise your Creator, and love Him always. God made you feathers to wear, wings to fly and whatever you need. God made you noble among His creatures and gave you a home in the purity of the air, so that, though you neither sow nor reap, He nevertheless protects and governs you without your least care.12

In Birdman, Lara creates a veritable registry of birds that appear in the Bible and in Biblical tradition (75-78). According to Lara:

Colonial Andean art is full of birds and feathers, perhaps more so than in any other region of Latin America, and certainly more than in European art […]. In a church mural in Oruro, Bolivia, depicting the Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, birds assist an archangel in preventing the first parents from re-entering the Garden of Eden. Spanish settlers were dazzled (97) […] particularly by the polychromatic birds -the parrots, macaws, and toucans- and the fact that they could mimic speech. Even for today’s tourist, a visit to the Andean highlands or the Amazonian lowlands is an otherworldly experience, not least because of the region’s birds. Peru is home to 1800 species, most of them year-round residents (59).

In pre-colonial times the art of the Andes was expressed in weaving and pottery. Marianne Hogue in her essay “Cosmology in Inca Tunics and Tectonics” reminds us that “Textiles naturally possess close associations with the life-sustaining world of plants and animals, whose raw materials were transformed (primarily) by Inca women into objects of utilitarian and religious significance.”13 It is certainly not surprising then to find European artists in South America as well as native artists trained by Europeans in the Andes creating landscapes of European topography yet filling their canvases with Andean flora and local birds -a veritable marriage made in Heaven.

Beyond their economic importance, birds inspired craftsmen creating colorful textiles, elegant metal adornments, and ceramic vessels. Pelicans, cormorants, waders, owls, condors, vultures, ducks, and hummingbirds were sometimes depicted with great realism and beauty, other times portrayed as supernatural winged creatures. The prominence of birds in [Andean] art reflects their importance in mythologies and ritual performances.14

Francis in the Sky

The quintessential winged figures are, of course, angels. “As in the New World, seventeenth century Europe witnessed an explosion of angelic art and an abundant display of wings” (143). A cult of angels emerged that fairly dominated religious paintings. “One did not mess around with these fearsome creatures,” Lara writes: “witness the terrors they inspired in Jacob, Isaiah, Ezekiel, the shepherds of Bethlehem, and even the Virgin Mary”(17). Influential in the development of “angeology” was a Jesuit and great admirer of St. Francis, Andrés Serrano who suggested that, in the advancement of converting Indians, substituting angel veneration in place of native deities, would lead to success. And, Lara adds: “One could say that angels are, in effect the real huacas and apus of the new Christian dispensation -and good role models as well” (99). Among other serendipitous syncretisms were the ancient gods with wings already in the Andean pantheon.15 In Birdman, pictures of petroglyphs and of exquisite, colorful textiles woven with winged gods attest to beliefs in flying men in the earliest Andean cultures which Lara lays out in detail (fig. 7).

Andean Christians of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries… believed “the witness of their eyes” […] that Francis has wings and Francis flies through the air to accomplish deeds similar to the birdmen of their Inca, Chanca, Moche, Cañari, and Aymara past (259).

How lucky the missionary friars must have felt to discover that the natives already believed in “angels.” Syncretisms aided in bringing the populations of the Americas into the Christian fold more rapidly, and, because of this blending, Christian worship in Latin America is unique in its beliefs and practices to this day. The successes of the missionaries in converting the natives, nevertheless, faltered in the beginning. In addition to the cruelty of the Spanish settlers who treated natives as slaves, “the immensity of the Andes, the extremes of altitudes and temperatures, and the challenges of travel through forbidding terrain were obstacles surmountable only by the most hardy and adventurous souls” (83).

Delightful examples of Serrano’s syncretic recommendation to substitute angel veneration in place of native deities are blended images which exist only in South America where there are paintings of “angels riding shotgun” as Lara dubs them (98). These archangels wear a hybrid costume of the dandyish, lacey jacket of a Spanish noble over an Andean tunic and something akin to a broad brimmed South American sombrero sporting enormous imported ostrich feathers (fig. 8).

In their hands, as elegant as Arthur’s sword, is a long-barreled harquebus shot gun, not threatening, but hardly comforting. They are as startling as they are unique.

As so often in his writing, Lara puts great notions into pithy sentences: “The conquest had been the result not only of the encounter of two political empires, but more importantly, a collision between two theocracies” (91).

Indeed from one point of view, it was not the failure but the success of conversion that threatened Spain […]. Compared to Native Rebels, the Spanish looked like rather lukewarm Christians […]. The true Christians were now the Indians. They were ready for the revolutionary proclamation of a truth they had long suspected -namely, that their Spanish oppressors were demons, heretics, and excommunicated sinners.16

A form of eschatology was not unknown to the peoples of the Americas. In the Andes, as in Aztec Mexico, the end of the world could be forestalled only by sacrifices to the gods. The Andean concept of pachacuti underlay the native world view encountered by the missionaries. Pachacuti, or “a radical cosmological shift -literally a revolution of time and/or space […] refers to the notion of regular episodes of the cataclysmic destruction and re-creation of the world” (67). This concept was enough like the eschatological predictions in the Bible book of Revelation for the missionaries to exploit it as Francis did. Pachacuti made perfect sense in a land where people lived with fear of volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. Perhaps the most devastating volcanic eruption in the Andean region occurred near the beginning of the colonial regime on January 1, 1600, near Cuzco. Despite hot lava and falling ash, Lara’s description of it is chilling. The missionaries wasted no time in preaching the end of the world and, therefore, the urgency of baptism and confession. Surely God was punishing the people for their pagan beliefs.

Following the volcanic eruption and earthquake of 1600 and another devastating earthquake in 1650, the need for restoration of damaged buildings and churches made it possible for indigenous artists to demonstrate their talents and gave birth to what is known today as the “Cuzco School of Painting”(119). Before long, wings on St. Francis in Andean art were de rigueur. The native artist, Basilio de Santa Cruz Pumacallao, was commissioned to paint a series of thirty scenes of the life of St. Francis for the cloister in the Order’s monastery in Cuzco. Santa Cruz painted the saint with gold-tinted wings above a landscape that includes Joachim de Fiore writing his apocalyptic tome (120-124). The cover image on Jaime Lara’s book comes from one of Pumacallao’s murals (fig. 1).

Figura 1 . Basilio de Santacruz Pumacallao, La Profesía, imagen tomada de Lara, Birdman of Assisi, 122.

Several copies of Santa Cruz’s series, some with additional scenes, were completed over the next century. A mural in a series painted for a nunnery in Santiago de Chile depicts Francis with wings whose outline, like those of many native birds and angels, are a glow-in-the-dark red. Again with Joachim de Fiore, Francis is seen with sword in hand defending the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (148). Other artists completing their own commissions of the series, such as those by Francisco de Escobar in Lima, were now placing St. Francis in the air with wings that varied in color and were often of a dramatic length (152-154).

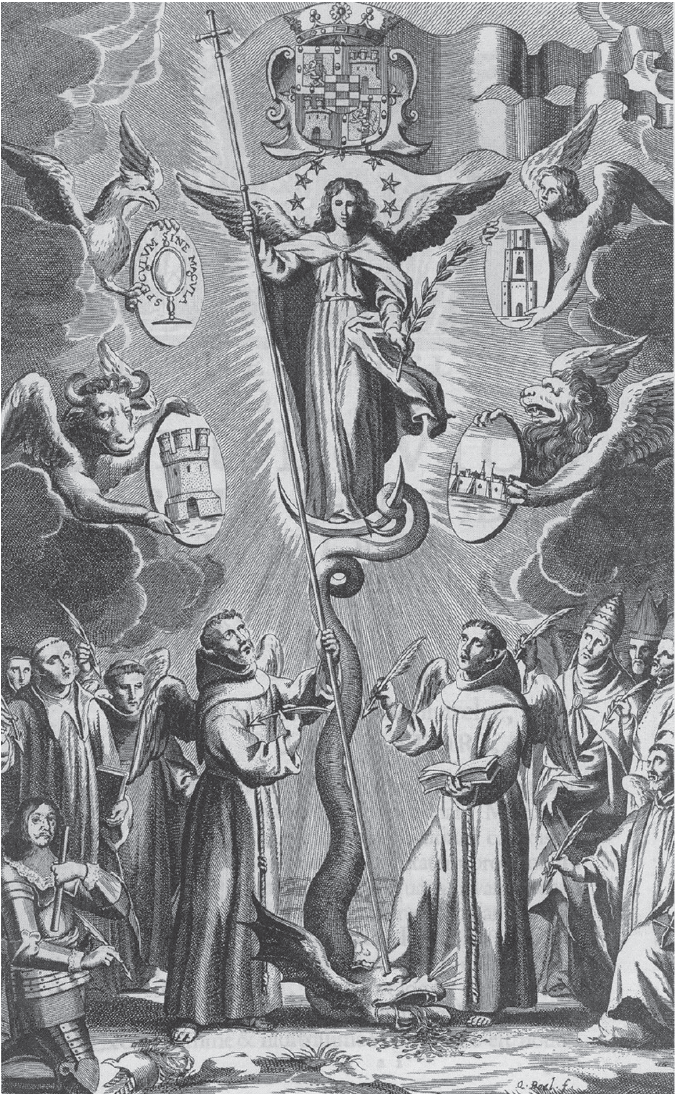

Friar Pedro Alva y Astorga, a Franciscan scholar of renown (b. 1601 in Spain), was another important influence on images of Francis in the air. He grew up and was educated in Cuzco, to which his family had emigrated. Later he moved to Belgium where he founded a publishing company. Although living in Europe, his influence “was alive in the viceroyalty of Peru through his students and publications and through the teaching of scholars […]. In Cuzco, copies of Alva y Astorga’s books were housed in the friary library, and each of them offers some image of flying Francis….” (142) (fig. 3).

Figura 3 Alva y Astorga, Militia Inmaculate Conceptionis, portada tomada de Lara Birdman of Assisi, 149.

As a winged figure, St. Francis, like archangels, now had powers of intercession and retribution and even of vengeance. In Bolivia, Mexico, and Cuzco, the winged Francis defended the doctrine of Immaculate Conception (147-151). Francis aloft in Lima and Quito participates in the apocalyptic end of the world and fights the demons of the book of Revelation. By the end of colonial rule in the Andes, St. Francis had become a paragon of angelic righteousness, the new Redeemer, the alter-Christus, the Second Coming.

In the Andes the winged Francis also became 3-dimensional. Statues of Francis, created mostly for the use of confraternities in religious processions and festivals, have made the flying saint a folk image. “Modern Indians dress and treat the winged Saint Francis […] in the same way as their ancestors treated the Lord Yucyuc. They also regard Francis as a shaman, one who controls atmospheric phenomena, heals, flies, acts as psychopomp, and knows the ‘secret songs’ of birds” (72-73) (fig. 2).

Figura 2 Melchor Guaman Maytax escultura processional de San Francisco, 1960 Cuzco, Perú, imagen tomada de Lara Birdman of Assisi, 8.

Throngs of people from peasants to potentates still attend parades in which floats of scenes from the Bible and those lauding Mary and the saints, especially the winged Francis in the sky, are celebrations of worship and entertainment.

Lara has been clear that his purpose in writing Birdman is to bring us an evolution of Francis in the history of art at which he succeeds incomparably. For Francis as a spiritual phenomenon, however, we are more likely to turn to passages like the following from G.K. Chesterton:

Now in truth while it has always seemed natural to explain Saint Francis in the light of Christ, it has not occurred to many people to explain Christ in the light of Saint Francis […] Saint Francis is the mirror of Christ rather as the moon is the mirror of the sun. The moon is much smaller than the sun, but it is also much nearer to us; and being less vivid it is more visible. Exactly in the same sense Saint Francis is nearer to us; and being a mere man like ourselves is in that sense more imaginable (118).17

In his final chapter, having summed up his purposes and offered a valuable lesson in Art Appreciation worthy of Albert Barnes, Lara concludes:

To tell the story of life, one needs symbols that unite the concrete sensuousness and interrelatedness of existence with images of a universal destiny […]. One of the principal reasons for the spread of Christianity in the New World was that it had concrete stories to show and tell: mega-narratives about origins, first parents, heroes and villains, failures and successes, happiness and sorrow, health and suffering, living and dying (259).

That St. Francis should end up able to defy gravity like an angel over the Andean landscape is one of the beautiful myths and miracles of religious art. Francis as an icon in art continues to capture our imagination, and, in our day, the current Pope, although of the Jesuit Order, has chosen to honor the saint by taking the name Francis and thereby creating new interest in art that depicts him.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)