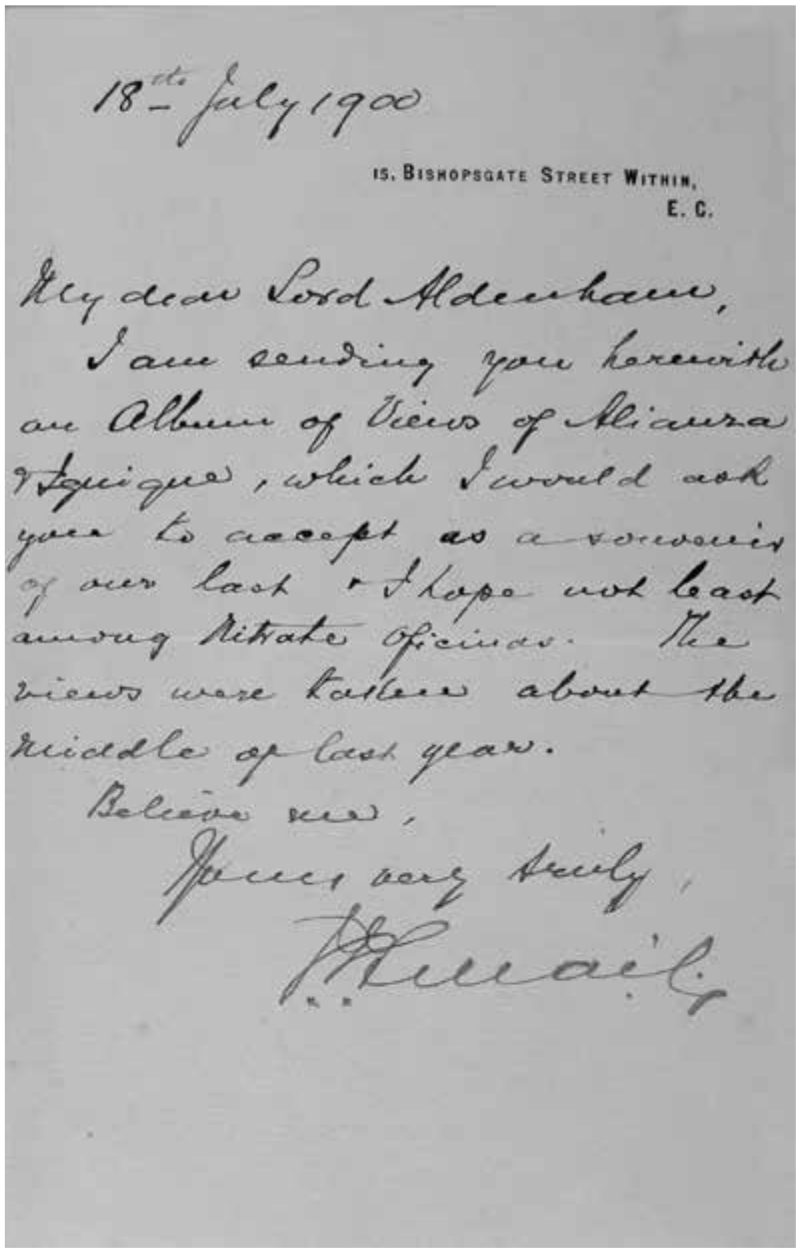

On 18th July 1900 Mr. Smail wrote to Henry Hucks Gibbs. He addressed him by his title:

My dear Lord Aldenham,

I am sending you herewith an album of views of Alianza Iquique, which I would ask you to accept as a souvenir of our last but I hope not least among of Nitrate Oficinas. The views were taken about the middle of last year1 (Fig. 1).

1. "Letter to Lord Aldenham from Mr. Smail," 18th July 1900, in Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, album 12, Fondo Fotográfico Fundación Universidad de Navarra/ Museo Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona.

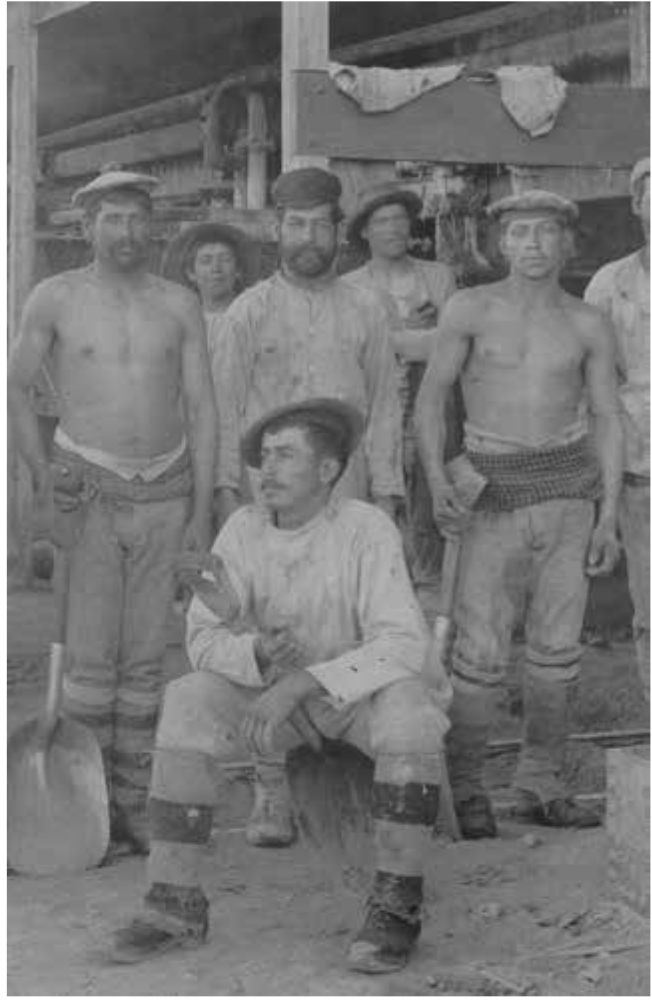

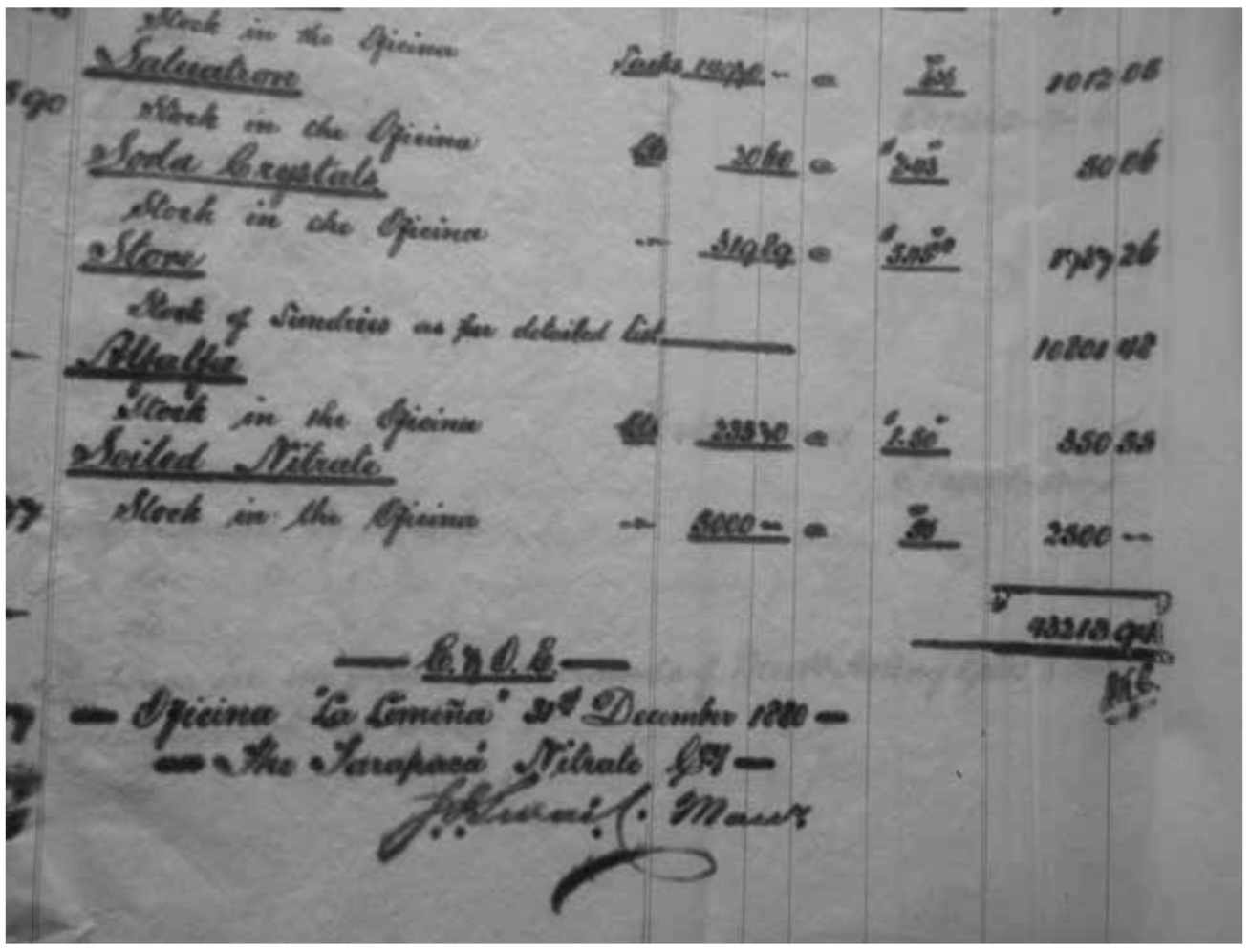

Mr. Smail was a manager of nitrate companies mining in Chile owned by merchant house Antony Gibbs and Sons; he was accustomed to corresponding with their London office, sending financial accounts to the head of the house (Fig. 2).2 The "Album of views," which has the title Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 embossed on its cover, contains around 90 photographs of the nitrate industry in the Atacama Desert of Chile, concluding with panoramas of the nitrate ports. The desert was intensively mined for nitrate from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century. The industry was driven by British capital and investors that colonized an inhospitable place, an almost waterless environment. Machinery was imported from Britain and men to labor, Chilean, Bolivian and Peruvian, were brought and bound through an enganche system to live in the nitrate Oficinas.3

2. Manager's Report, Tarapaca Nitrate Company, Antony Gibbs and Sons Limited, London Metropolitan Archives.

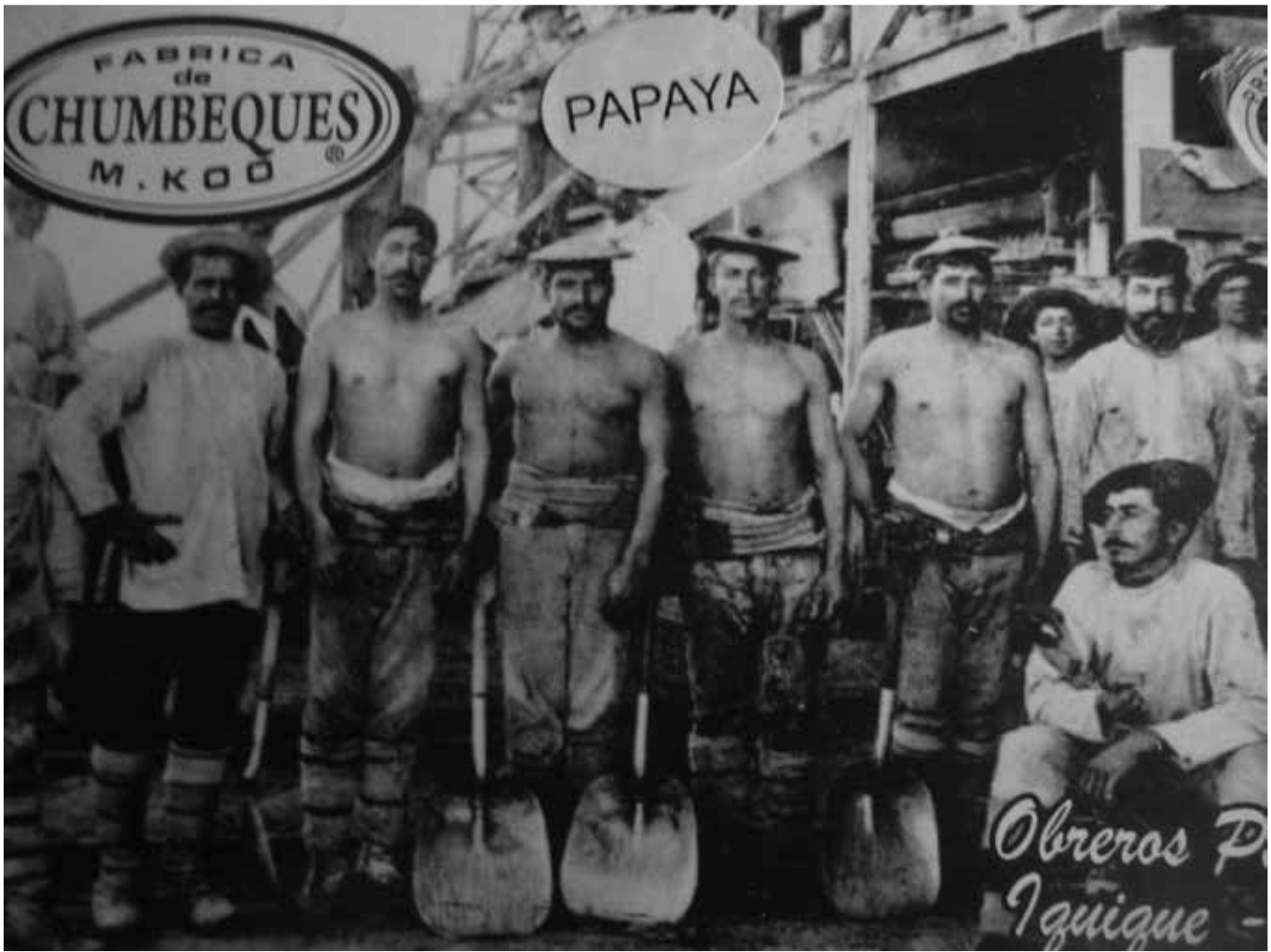

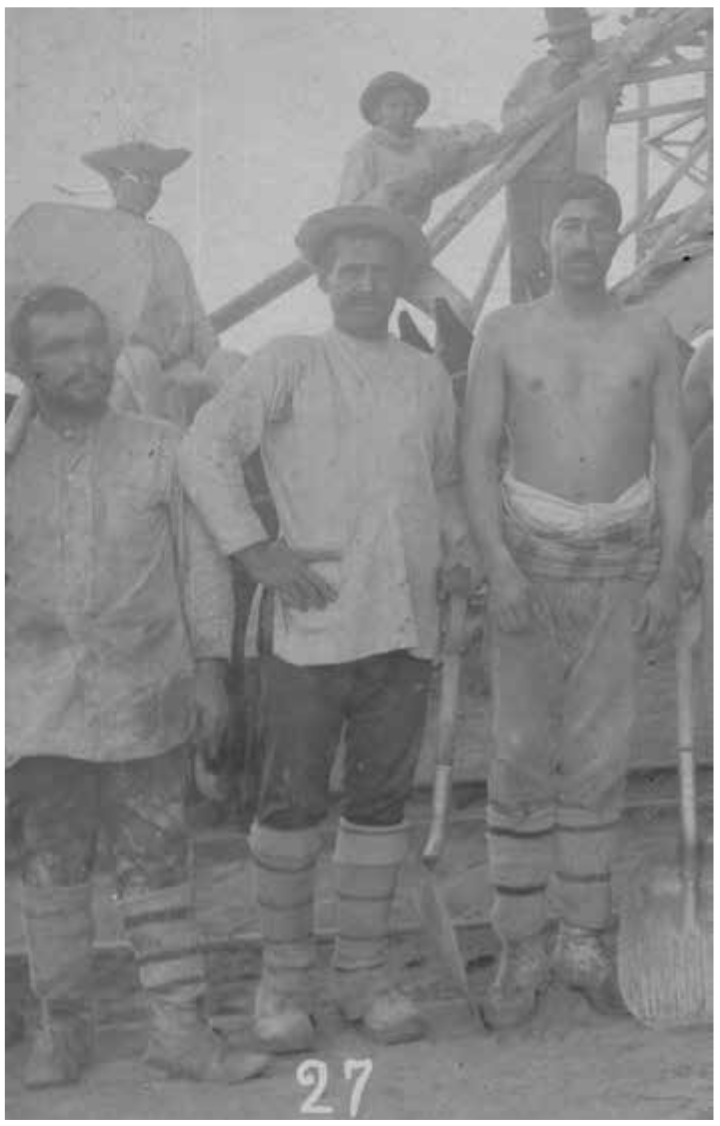

The Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album contains one image of contemporary political significance: the photograph numbered 27 (Fig. 3) presents a row of nitrate miners, shovels in hand, entitled "A Group of Desripiadores"; it has been deployed in commemorations of the Escuela Santa María massacre, when the killing of hundreds of striking nitrate miners, railway workers, cart drivers and artisans by government troops took place in Iquique on 21 December 1907. A week before, 5,000 nitrate workers had walked from the oficinas along the railway lines that cross the pampa to rally in Iquique; they waited in the large courtyard of a school called Santa María while their representatives, including José Briggs and Luis Olea, presented their demands: an end to payments in fichas, the nitrate company tokens that were the currency of the overpriced company stores; wage stability with the establishment of an eighteen pence peso; safer working conditions, especially around cachuchos, the mechanism for crushing caliche, the desert rocks containing nitrate; honest working practices, particularly an end to processing the low grade caliche for which workers had been refused payment; more schools and free evening lessons for workers; an amnesty for strikers. The nitrate companies, merchants and bankers refused to negotiate. Regional Governor intendente Carlos Eastman declared a state of siege and ordered nitrate workers back to the pampa. When they refused, the military, led by General Silva Renard, used machine guns to fire on the strikers and then charged at them with mounted troops and bayonets. "Iquique, site of the greatest labour uprising, remains part of the class consciousness of militant labourers" writes Michael Monteón.4 The Santa María massacre is, summarizes Lessie Jo Frazier, "the central symbol of repression that led to the formation of working-class consciousness."5 It has been commemorated with annual rallies at the school and, most importantly, recalled in song. The Cantana Santa María of Iquique was written and popularized during the 1970-1973 Popular Unity period. The 1907 killings became a more complex symbol of class struggle in Chile: "an allegory for the overthrow"6 of Salvador Allende's government by General Pinochet with his United States supporters.

The figures of nitrate workers photographed some eight years before the Santa María massacre are an embodiment of the heroism of manual labour, collectively organized. Their forms circulate far beyond their position in the Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album;7 they have been remodelled in metal, digitally reproduced on Left radical blogs as well as used to represent the regional history of Iquique to tourists (Fig. 4). The image is arresting (Fig. 3); it offers the possibility of catching a glimpse of the work behind nitrate mining, of the experience of shovelling the desert earth, of the material conditions of laboring in the desert: a flash8 of a past reality. It contains, in Walter Benjamin's words, a "tiny spark of contingency":

No matter how artful the photographer, no matter how carefully posed his subject, the beholder feels an irresistible urge to search such a picture for a tiny spark of contingency, of the Here and Now, which reality has so to speak seared the subject.9

Maybe. Hopefully. We shall see. This analysis examines the Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album as a fragment of an archive of the British nitrate industry in Chile. I offer a reading of its sequence of photographic images. Space allows pausing upon only a few of the 90 images to consider photographic practices used to record the mining exploitation of Atacama Desert.10

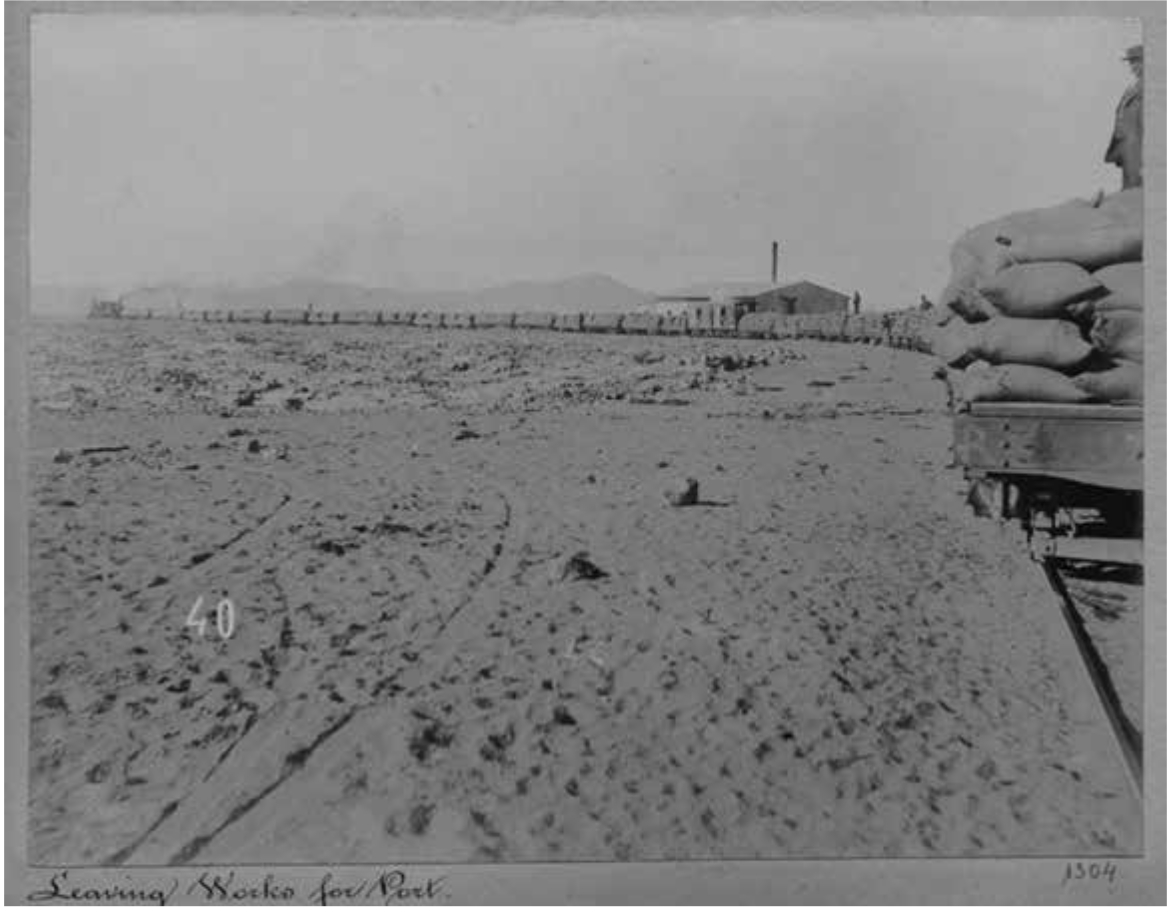

The first image, the number 1 scratched onto its surface, is, I would suggest, one of the most important of the album (Fig. 5). Initially, it might appear rather blank: an empty sky, pale sepia produced by colodion printing process, hangs over a flat desert, which is only a little darker in colour. The rocky surface creates some shadow. The nineteenth century camera has captured details of surface. The earth has texture but, with its emptiness, the sky moves to the foreground beneath and below it. The railway tracks established lines of perspective along the left of the image; the right hand track, a long straight line with a dark sharp shadow, propels the viewer towards a building and then a wall. Also distinguishable because its shape is darker, straighter than the surface of the desert, a wall cuts across the horizon where the desert fades into the sky, providing another line of sight through a series of structures that continue to draw the viewers attention across the image towards a distant factory building. Entitled "General View of Grounds and Works" (Fig. 6), the image prepares the viewer for the following 90; it sets the scene, indicates everything that is in store.

Rather than blank, the empty, flat image is full and quite dynamic. The railway tracks generate a geometrical order; the lines square off the desert. The view's photographic arrangement posits an industrial topography; it shows a worked and controlled landscape. Within a measured boundary, the desert's uneven surface becomes a nitrate field, one of the "Grounds" of industry, to use a word taken from the image's written title. Tracks and walls are furthermore, lines of movement, visual and geographical trajectories. Their destination, on the far right of the horizon is the Oficina. Its smoking chimney, a sign, or more precisely, an index of industrialization (Fig. 6). The viewer's visual path simulates that of the train, on which the photographer carrying his camera and other photographic paraphernalia would certainly have travelled. Train and photographer, with those who have flicked through the album trailing behind them, are heading for the Oficina. The opening image promises a journey and, indeed, a journey does unfold through the album.

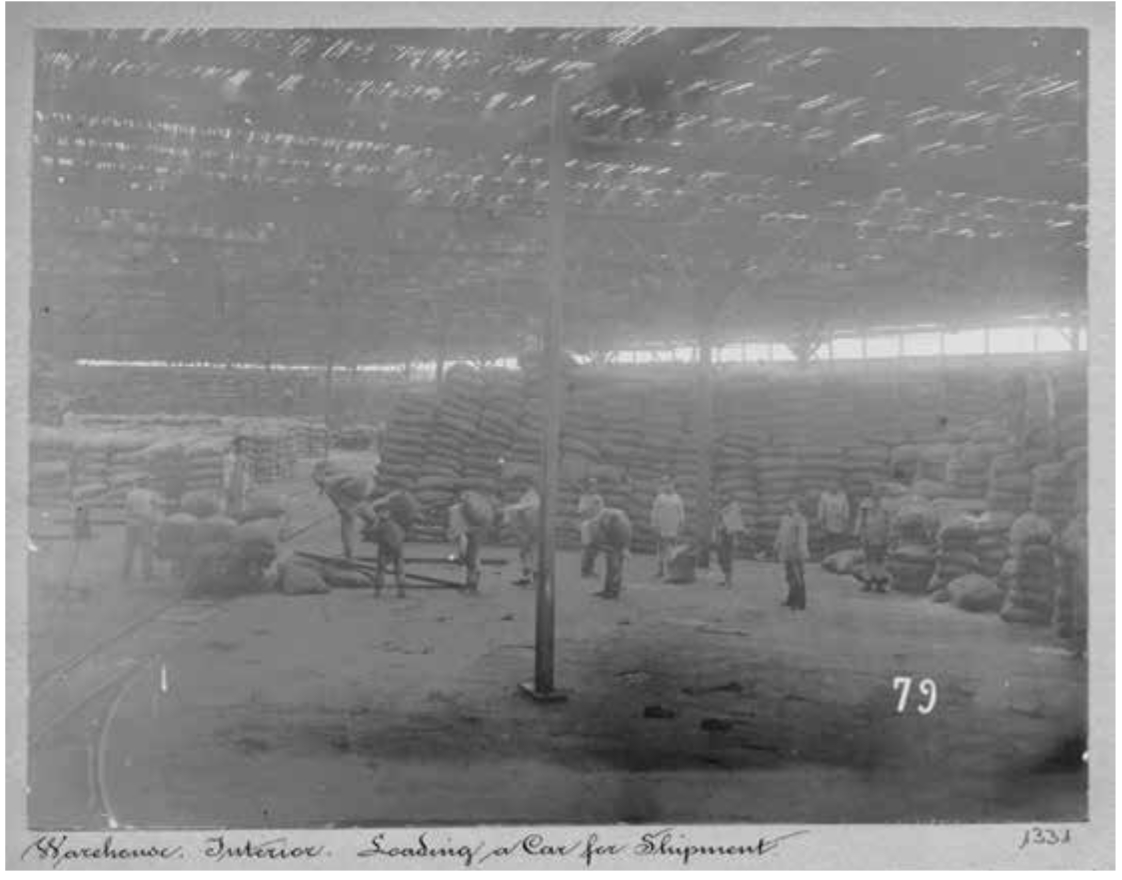

The first 40 photographs trace the mining, processing and transport of nitrate; its transformation from desert rock, a mineral deposit, caliche, lying just beneath the surface, to a chemical, bagged and ready for transport (Figs. 7 and 8). As nitrate changes its material state, it crosses the landscape: each photograph shows an industrial stage and is a geographical frame. When the nitrate is loaded onto the train to leave the desert (Fig. 8), the camera's movement and the viewer's gaze behind it, rest on the Oficina itself. A tour of the nitrate works and nitrate town in 20 photographs opens with a view of the general stores and concludes with one of the administrator's house (Figs. 9 and 10). This sequence is an interlude. The image that immediately follows, the selection of which seems to use editing techniques that characterised early moving film, shows the arrival of the train pulling sacks of nitrate to the port of Iquique (Fig. 11). It is as if the nitrate town tour took place while the bags of nitrate were travelling across the desert to Iquique. Geographical frames are also time frames. When the train enters Iquique, the viewer joins nitrate's journey. The next sequence, ten or so photographs, tracks the movement of nitrate as it is transferred from vehicle to vehicle, stack to stack, from train to warehouse, warehouse to dock, boats to ships (Figs. 12 and 13). Here is evidence of its export, a measurement of the quantity of nitrate. The effect of the images is cumulative: piles upon piles of stock are a display of abundance, always a representation of wealth.

12. "Warehouse Interior. Loading a Car for Shipment," Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 79.

The album Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique presents a photographic sequence that is spatial, material and temporal: from the desert to the sea, from rock to commodity. Furthermore, there is an evocation of historical time within the sequence that makes industrial process appear as historical progress. It is the second image of the album-that which immediately follows the opening photograph of a worked controlled desert landscape, an industrial topography- which opens the historical sequencing. Entitled "Virgin Nitrate Grounds," it is almost featureless, a photograph of nothing, no event, no action (Fig. 14). It consists of two blocks of colour: a pale earth and an even paler sky. It displays the desert as vast empty expanse, an uninhabited land, waiting for something to happen. The human figure is scaled small against the desert to demonstrate its emptiness and readiness. Two men on horses are positioned in the centre of the photograph; their forms are indistinct; only an outline is discernible. The horses are held (one by the reins) facing each other, angled to form a gateway into the desert vanishing to a point between them. Across from each other, the men look into the distance. The profile of their clothed bodies, the shape of their hats not their faces visible, indicates they turned away from the camera, encouraging the viewer to gaze as far as their eyes can see, to the vanishing point. The undisturbed surface of the empty desert spreads out before them. In this geographical time frame, there is no smoking chimney, no signs of industry. In the photographer's time, real time, if you like, he has simply pointed his camera away from the Oficina Alianza, the fully operational Oficina, that he was heading towards as he travelled on the train. He has produced another view of the desert seen as the Oficina's past; thus his sequencing of photographs becomes an account of the desert's industrialisation; it shows the industrial transformation of the Atacama desert as a historical as well as daily operation.

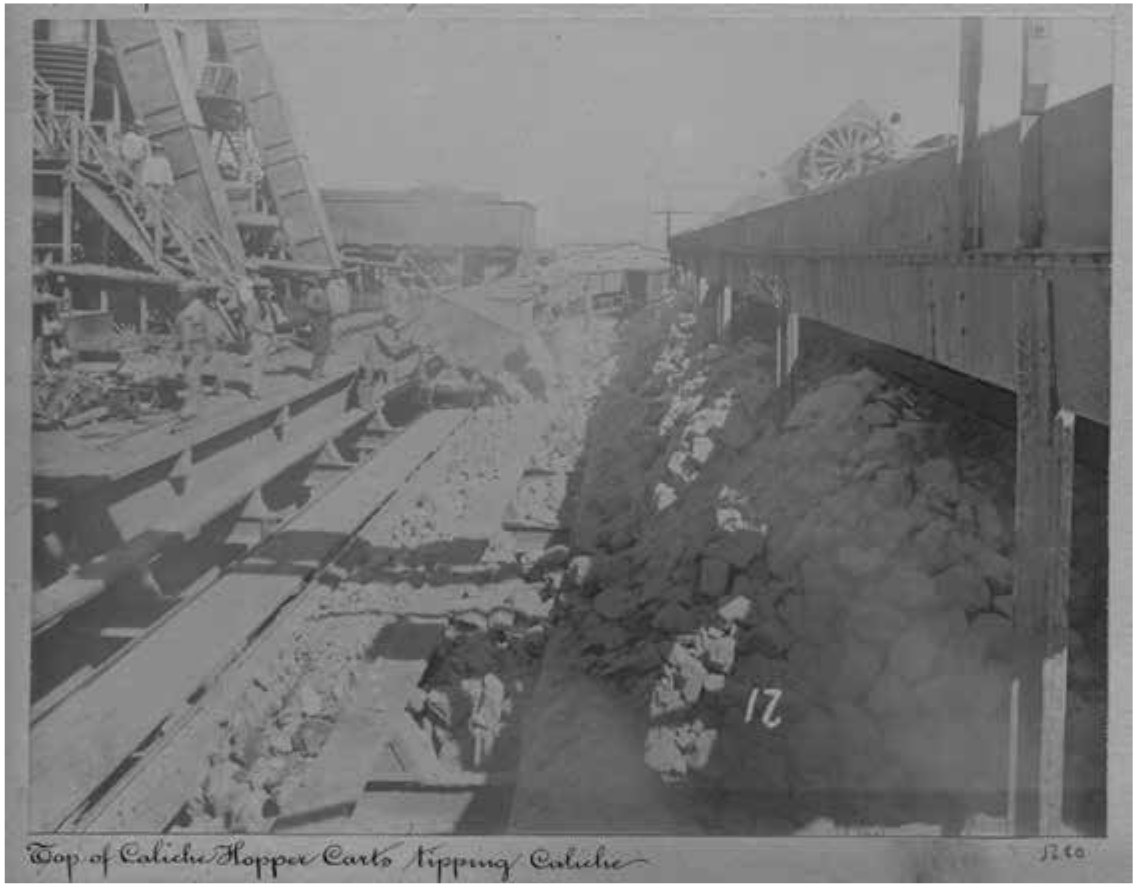

In the album, the desert landscape dominates (expansive ochre fields under large empty skies), until the arrival of technology. The album's seventeenth frame is a well-organised image of industry (Fig. 15). The tracks, girders and planks (the railway carrying carts of caliche and regular openings of the crusher's hopper) extend from bottom left to centre providing lines of perspective around which the image's elements are drawn into symmetry and balance. Steep sided structures, exposed constructions reproducing metal forms, rise on either side of the tracks. Industry lies between, represented by activity and quantity, productivity, to use a term taken from Economics. Men engage in purposeful stances within the industrial architecture and oversee mounds of materials. At the very centre of the image, where lines of perspective converge, is its defining moment, a stage for the industrial process' announced by the title: "Top of Caliche Hopper Carts tipping Caliche." Three men reach and hold the cart as dusty rocks pour from the bottom and spill from the top (Fig. 16). The foremost figure's face, whose leaning body is aligned with the cart to become part of the shape and movement of the tipping caliche, is turned upwards towards the camera. His glance punctures the image, alerting its viewers, us, that this moment is being presented. But the image's other elements combine to encourage the dismissal of his stare, and the challenge it implies, in favour of the documentary requirements of nineteenth century industrial photography. The cart and its handlers might have paused for the camera but the heavy loads stacked behind them ratify that the sight of a tipping cart of caliche is routine in nitrate processing, in fact, it is repeated in the image: a dust cloud pours from a mule drawn cart, positioned above right. The viewer can see enough to assume that this happens often.

15. “Top of Caliche Hopper Carts tipping Caliche,” in Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 17.

These moments in the journey of nitrate are not merely a record of where the photographer stood nor is the narrative of nitrate his invention. I am assuming the photographer is male, though I do not know his name and have no other sign of his identity. Records of him have unfortunately been lost or overlooked; his anonymity is an historical accuracy of a kind. The photographer of Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 cannot be distinguished as an individual practitioner because his work reproduces standard photographic forms of the late nineteenth century. The sequencing of images was created through considerable careful editing, their numbering and renumbering is discernible on some plates (Fig. 15), but the composition of the views of the desert landscape and nitrate industry dutifully follows the conventions of late nineteenth century photographic practices. The extraordinary spaces of the Atacama Desert are presented as an industrial scene, like other industrial scenes. The desert is framed through the practice of industrial photography, which was well established by the time the album was compiled in 1899. The historian of the art of the engineer, Francis Pugh, states:

During the latter half of the nineteenth century industrial photography became one of the principal means for recording and publicizing the achievements of British industry, so that by 1900 there was hardly an industrial sector which did not make use of photography in one form or another11

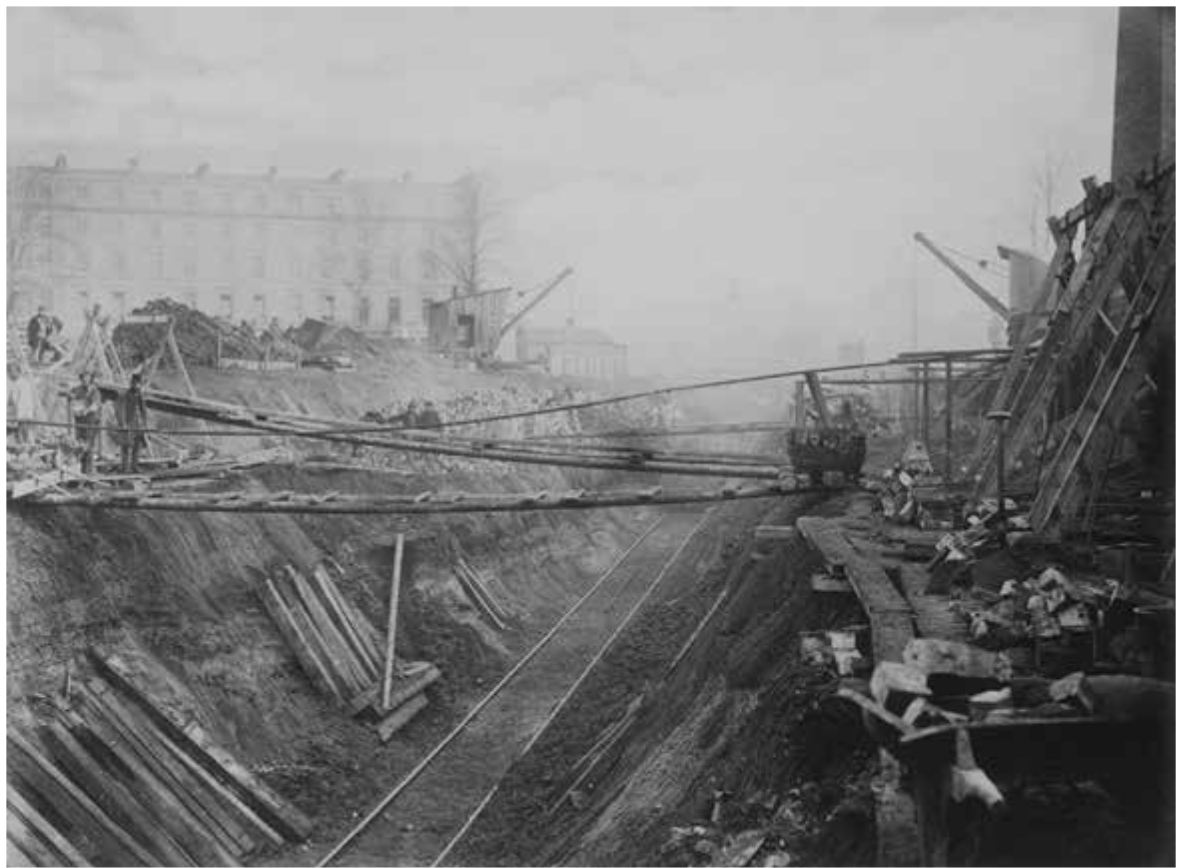

It was from the mid-nineteenth century on when photographers with some professional status were commissioned by engineers or contractors, to produce photographic records of large-scale industrial schemes. Typically, it was ambitious structural interventions on landscapes that were documented, such as bridges or tunnels for railway lines. Henry Flather's Construction of the Metropolitan and District Railway (Fig. 17) is an important example of this photographic practice. Many of Flather's 64 images contributed to the establishment of the conventions of industrial photography; I would draw attention to just two images. One, Figure 17, is a perfectly arranged scene of industry. Flather deploys pictorial practices to provide a frame through which industry can be represented; he organizes the view of industry, brings order to the disorder of an unfinished industrial work. His photograph has the formal arrangement of a landscape painting:12 a left to right, top to bottom axis creates movement across the picture plane. On either side of this axis, the railway cutting across and the subject of the photograph; alongside exposed surfaces of dark dug out earth and lighter rocky shelves lie heaps of stuff, piles of wooden planks awaiting use, barrows of blocks ready to be carried away. An unfinished scene is drawn into a balanced arrangement. A symmetry between two cranes suggests an archway. The heaps of temporarily discarded stuff form geometrical patterns, repeating rectangles or the lines of isosceles triangles. The incomplete nature of the scene is busy but not chaotic; it is an image of the moment of material transformation. Human figures hold a small part in this scene; they stand within its industrial structures, as if emplacements, belittled by the amount of materials and the scene's dimensions and scale.

Another image of the Bayswater Excavations by Flather is captioned A gang of workmen around a steam crane which is removing spoil from an excavation at Craven Hill (Fig. 18). It has the human figure, the worker's body, a group of laboring men, as its subject. They are turned to face the photographer, the camera and, once the shapes of light upon photographic plate are fixed in chemicals and reproduced, they face us, the photograph's viewers. They have been positioned ascending and descending the steam crane, another balanced classic painterly arrangement. The figures form sight lines from the left and right that move towards the center of the image, to the pulley mechanisms, cogs and wheels, the steam pipe atop it all, the pinnacle of the image. The group of laboring men presents the technology of industrial work and themselves; the poses their bodies hold can be read as industrial labor. The foreman positioned center right holds out his chest and fills out his waistcoat to demonstrate his authority. The white jacketed workers' stance, front leg bent, shovel held, back leg straight, does not simply display his type of manual work but also his readiness to work. The group of laboring men are not shown with their backs bent in labor (another trope of industrial photography). We see they have stopped to be photographed, but labor is the photograph's subject, as it is also represented in the Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique album's 27 image (Fig. 3).13

18. Henry Flather, A gang of workmen around a steam crane which is removing spoil from an excavation at Craven Hill, Bayswater Excavations, 1866-1868, © Museum of London.

A row of nine nitrate workers confronts the viewer. They do so because they have been lined up directly in front of the photographer and have held their positions. The figure on the far left is posed as for an individual portrait: his gently angled body weighted on his back foot, his face and glance tilted upwards, he carries a token of his identity, the shovel (Fig. 19). The rest of the row of nitrate workers has simply faced the camera: a full-length frontal view of their entire body is plainly visible: legs straight, arms to their sides, faces looking forward. They appear to await a military inspection; nitrate workers on display. Yet, they do not entirely present themselves. Their presentation is arranged within the image, through the photograph's composition. The row of workers is mediated by a single figure in the foreground (Fig. 20). Seated on his shovel, beneath eye level, he does not block out the view of the nitrate workers; moreover, to use metaphors stemming from performance, he announces them. In the background there are nine figures (Fig. 3). Their faces less distinct, their bodies partially visible, they fade into the image's architecture. Five figures with the smaller frame of a child are evenly spaced ascending wooden stairs, and function as supporting cast to the main players. Five of a row of nine nitrate workers are bare-chested and four stand together in the middle. If the row is the main performance; they are its centerpiece. All other nitrate workers are fully clothed in every other image in the album. Desripiadores, those shoveling waste of nitrate processing from boiling tanks, worked with their shirts off. One female North America observer, Mabel Loomis Todd, noted they were half-naked.14 Perhaps, then, in a moment of rest from work prompted by the act of photography (the interruption of their routine by the photographer's arrival, the installation and adjustment of his equipment), some men cooled and dressed, or others felt the heat of the day and undressed. Two white shirts hang over the wooden structures supporting the Oficina's boiling tanks, the collar-less one, a worker's garment, just visible. Unintentional or otherwise, this is a show of strength: physical, manual, masculine. That much can be seen but its meaning is not clear, neither in 1899 nor now. Classical and primitive subjects wear bare chests in all kinds of imagery from sculpture to comic strips: ancient warriors and colonial peoples.

To try to understand the contradictions of such a show of strength, I would like to consider that moment of interruption, the act of photography. When the photographer was ready to take his shot, did he fear asking the nitrate workers to appear fully dressed? Or, did they reach for their shirts and he told them to stand for the photograph without them? In that moment, to whom did their strength belong? There are two figures who do not stare at the photographer or at his camera but look to their left: the seated figure in the foreground and an upright figure parallel to him, behind the row of nitrate workers. They seem to be looking at the same thing or the same person; they wait for the photograph to be taken, the moment to pass, to then perhaps receive a sign from the foreman, el capataz, to get back to work.

Like Flather's Bayswater Excavations photograph, the "Group of Desripiadores" is an image of work arrested, but industrial labor is its subject. I am not arguing that the photographer of Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique had seen Henry Flather's photographs or admired the work. My proposal is that by 1899, when he arranged his tripod on the uneven surface of the rocky desert to point his heavy camera towards an empty landscape before turning to focus upon the operations of machinery, a way of picturing industry was already in place. Furthermore, by the 1880s, according to Francis Pugh, photographic documentation of industrial works had become part of that industrial work, organized by the engineer, contractor or company carrying it out. At this time, he states "the engineer-photographer becomes a more familiar figure."15 The photographer of the album is just another industrial worker,16 and the less we know about him, his relationship to the nitrate companies, the owners of the machinery or the railway, the more the photographs appear to record the historical inevitability of industry, that the desert was there just waiting to be industrialised, rather than his own existence which was contingent upon industrial relationships.

Each industrial stage of nitrate mining at the Alianza Oficina documented in its album was "entwined" with,17 even determined by, competitive relationships of accumulation of capital. If it is not a contradiction in terms, nitrate trafficking was a matter of competing monopolies. Following Chile's victory in the War of the Pacific over neighbours Peru and Bolivia, the natural monopoly of sodium nitrate of the Atacama Desert became the site of concentrated capitalist exploitation. Competition for concessions to mine nitrate fields and the railway routes from these desert fields to the Pacific ports led to the rapid expansion of nitrate mining and the industrialisation of the Atacama. One nitrate company, for instance (that owned by Antony Gibbs, John Thomas North, Balfour Williamson, Campbell Outram and Folsch Martin) worked several nitrate fields and owned the nitrate Oficina and warehouse in Iquique or Pisagua where sacks of stored nitrate awaited export to Liverpool, London and Europe. German farmers, who grew beets for cattle feed and liked the quickening effect of nitrate fertilizers, were important customers. The railways that transported nitrate from the desert to the sea were the "key" to profits and profiteering in nitrate.18 Railway companies charged nitrate companies for transportation. Monopolies reigned. High tariffs were charged per quintal (close to an American hundredweight) of nitrate. In 1887, British engineer turned financial speculator John Thomas North, bought 7,000 shares in the Nitrate Railways Company, a Peruvian firm owned by the Montero brothers, but registered in London in 1882. The following year, North became company director. Herbert Gibbs complained to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that "the monopoly of the nitrate railways was weighing unmercifully upon British capital invested in the nitrate works."19 Gibbs' objection to paying North's high tariffs and, more broadly, to his parvenu status in British nitrate trade, meant that the Alianza nitrate field remained unworked as they diplomatically pressed for a concession to build their own railway line, and until North's railway monopoly was brought to an end. Monopoly was the nature of the nitrate business.

Allan Sekula states that industrial photography was the form of monopoly capitalism: "institutionalized industrial photography characteristic of the epoch of monopoly capitalism."20 Are the images that comprise the Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album so bound to Antony Gibbs and Sons interest in Chile that they can only display the values of the monopoly's capital? The album holds a dual status; it is both a general and specific form. It is of a type, an example of industrial photography, a generalizable representation of a landscape transformed by feats of engineering: cuts, lines and movement made by massive metal structures and engines. But it is also quite a specific representation of Antony Gibbs and Sons interests. I use interest here to evoke at least three of its meanings: a scene that might attract attention, a matter of concern, and their business. Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 is an album of interest to Antony Gibbs for all these reasons. In Mr. Smail's words, it is "a souvenir" of "our last but I hope not least among nitrate oficinas"; the album Oficina Alianza brings a part of it into a London office. It is accepted as such. Photographic bounty is analogous to profitability. "My dear Smail" replies Henry Hucks Gibbs:

I am much obliged to you for the excellent photography of the Alianza [...] handsome volume [...] If the business itself produces a corresponding handsome result, it will be in great measure due to your zeal and ability, which are fully appreciated by my friends as well as by me.21

So where might the Benjaminian "spark of contingency" be found in "A Group of Desripiadores"? It must be there since it is the only image of the album that has been widely reproduced. It might be found in the nitrate workers' stance. Even without their shirts, they guard themselves. Their bare chests, a display of physical and collective strength for the photographer in Oficina Alianza in 1899, may be the spark. Quite out of chronological sequence, it illuminates the gestures of the nitrate workers lined up in front of General Silva Renard's troops in 1907. Micheal Monteon relates that when they surrounded the Escuela Santa Maria, "Labourers greeted the soldiers' arrival with hoots; some ripped open their shifts and dared the troops to fire."22 Or, the reality that has "seared the subject" is in the hands of a nitrate worker. The sixth figure from the left holds his shovel with an easy familiarity: thumb balanced on the top of the handle, fingers gently curling under it, resting but ready to hold it more tightly (Fig. 21). At first glance, there appears to be a perfect fit between hand and tool. The repeated act of shoveling, of laboring, can be seen in the image of physical familiarity. More details can be detected between the hand and the tool, the nitrate worker and the shovel: there is fabric wrapped around its handle. All visible shovel handles are similarly wrapped. Nitrate workers' dress have a number of fabric bindings; some, known locally as polainas, are bound around their waist and their socks to protect their skin from the abrasive mined material of the desert: salty, sharp nitrate and dusty, dirty ripio. The nitrate worker's gentle grasp over the folds of fabric wrapped around his shovel's handle reveals some of the hard labour performed in an inhospitable place. Thus, momentarily, the material conditions of mining in the Atacama Desert are captured in the photograph numbered 27 (Fig. 3) in The Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album.

Conclusion

Despite the orderly sequences of productivity and profit revealed by this "album of views" of the nitrate industry, I have been unable to suppress the "urge to search [...] for a tiny spark of contingency." There is a tension between the album of industrial photography and the photographs it contains, or at least one: "A Group of Desripiadores." They pull in different directions to reveal nothing less than the historical contradictions of industrial capitalism: pictured here is the inevitable opposition between mining monopolists and the labor of miners. In the photographed bodies of the ripio workers, we can see both industrial oppression and organised resistance.

The Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album is a document of industrial capitalism. Its long photographic sequence, which begins with desert rocks and ends with bagged commodities, highlighting the dynamism of machinery in this material and spatial transformation, is an account of industrial progress. Its articulation is dependent upon the practice of industrial photography, Alan Sekula's "characteristic" form of capitalist monopoly. The album Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 reproduced a series of scenes of industry that were already established views: the dramatically altered landscape, the force of machinery, the image of labour obediently coming to a stop. Plate 27, "A Group of Desripiadores" (Fig. 3), is just another of those "characteristic" forms of industrial photography wherein the workers' bodily strength stands as part of the documentation of the amassing of capital. Pasted into the album, their image was transported from Iquique to London, following the same path as the bountiful bags of nitrate and their detailed account books, to be received as an analogy of profit: a "handsome volume" that projects a "handsome result." In the photograph, capital assumes a visual rather than numerical form. Yet "A Group of Desripiadores" has been retrieved from the hands of monopolist merchant houses in London through the same process by which it advanced itself: photography. It is a "dialectical image."23 The light of the Atacama Desert that filtered back through the lens of the camera to react with the chemical covering of its plate left evidence of the reality of mining in Chile: the abrasive conditions of shovelling nitrate residue overcome by the collective strength of those who stood to face the camera and the forces that had brought them all there. §

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)