Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

versión impresa ISSN 0185-1276

An. Inst. Investig. Estét vol.34 no.101 Ciudad de México nov. 2012

Artículos

José Luis Cuevas and the "New" Latin American Artist

José Luis Cuevas y el "nuevo" artista latinoamericano

Christopher Fulton

University of Louisville.

Recibido el 30 de agosto de 2011.

Aceptado el 24 de agosto de 2012.

Abstract

José Luis Cuevas emerged in the mid-1950s as an independent artist who refused to subordinate his art to imposed standards and expectations. In his conflict with the artistic establishment he was defended by prominent critics and other artists of like mind and received crucial support from foreign sources, including the critic Marta Traba and curator José Gómez Sicre. He was heralded as an exemplar of the liberal spirit in Latin American art, and his frequent travels and personal associations placed him on an international stage. The present study of Cuevas's activities from the midfifties through the early sixties considers him as a paradigmatic case of the "new" Latin American artist and as an agent in the process of dissolving barriers between the national artistic cultures of the region.

Keywords: José Luis Cuevas; José Gómez Sicre; Mexican art; Ruptura; modernism.

Resumen

José Luis Cuevas surgió a mediados de los años cincuenta como un artista independiente que se negó a subordinar su arte a los estándares y expectativas de la época. En su conflicto con el establishment artístico fue defendido por críticos y otros artistas afines y recibió el apoyo crucial de personalidades del extranjero, incluyendo a la crítica Marta Traba y al curador José Gómez Sicre. Asimismo, fue proclamado como ejemplo del espíritu liberal en el arte latinoamericano, y sus frecuentes viajes y vínculos personales lo situaron en el escenario internacional. El presente estudio de las actividades de Cuevas de mediados de los años cincuenta hasta los tempranos años sesenta lo considera como un caso paradigmático del "nuevo" artista latinoamericano y como agente en el proceso de disolución de las barreras entre las culturas artísticas nacionalistas de la región.

Palabras clave: José Luis Cuevas; José Gómez Sicre; arte mexicano; Ruptura; modernismo.

José Luis Cuevas—a Mexican graphic artist, born in 1933—burst on the international scene in the mid-1950s with his drawings of depraved and forlorn subjects. An intense, private young man (fig. 1), he found himself suddenly thrust into the middle of a heated controversy between the defenders of politically oriented art and advocates of openness and freedom of expression, and within a short period he overcame his natural shyness to develop into an effective polemicist and model for progressively minded artists. In his own work he escaped the confines of Mexican national art by addressing universal themes about the human condition, and became an important personality in the wider Latin American region by traveling and exhibiting in other countries and cultivating relations with foreign artists and critics. This essay examines Cuevas's activities of the years 1954 to 1964, in an effort to gain a better purchase on the conflicts of the era and on the multiple forces that were then converging to produce a continental artistic culture, as well as to illuminate his own role in this process.

José Gómez Sicre and the launching of a young artist

A formative influence on the young Cuevas was exerted by a number of exiles from the Spanish Civil War, who introduced him to the wider world of European ideas and gave encouragement to his independent spirit.1 He became acquainted with the émigré artists Arturo Souto, Enrique Climent and José Bartolí, attended lectures by the philosophers José Gaos and Ramón Xirau, and was introduced to the poets Luis Cernuda, Luis Rius and León Felipe. However, more than any other individual, it was the author and critic Margarita Nelken who nurtured in him a life-long interest in the broad spectrum of European thought.2 She was thirty years his senior, and shared generously from her rich stores of knowledge and experience, especially of Spanish artistic and literary traditions. It was also Nelken who first gave critical attention to Cuevas's drawings, and in later years she continued to write approvingly about his art.3

An Iberian strain of melancholy and decay and a picaresque interest in low-life characters typify Cuevas's early work. While the prevailing fashion among Mexican artists of the post-war years was to venture into the countryside in search of pictorial subjects, he explored the capital's grim alleyways and seedy boulevards, and there discovered the secret, exotic life of its abject inhabitants—beggars, prostitutes, cripples, vagabonds, drunkards, knaves and ruffians of assorted kinds. Intrigued and captivated by such marginalized subjects, he also visited the psychiatric hospital La Castañeda to study its deranged inmates (fig. 2) and made a series of tormented ink drawings that contradicted in strident and disturbing tones the popular image of abundant, cheerful Mexico, of Mexico as a continual fiesta.4 The notes of cruelty, terror and isolation that chime in these images echo the tortured language of exiled poets León Felipe and Luis Cernuda, while the hard and intransigent line that describes the weary figures brings to mind the drawings of Bartolí, which Cuevas knew quite well.5

Yet before he stepped foot into La Castañeda and even before holding his first solo gallery exhibition, Cuevas caught the eye of a visiting official from Washington, D.C., named José Gómez Sicre (fig. 3), who had come to Mexico in the early months of 1953 to identify emerging artists with a progressive outlook like his own. Cuban by birth, Gómez Sicre served as director of the Visual Arts Section of the Pan American Union (PAU), which was the main operational unit of the Organization of American States (OAS), an alliance constituted in 1948 to foster inter-American relations and prevent the spread of communism in the Western hemisphere. As exhibition organizer and director of the PAU Art Gallery, he worked tirelessly to promote Latin American art and was regarded as one of the most knowledgeable critics in the Americas. During his stay in Mexico, he was introduced by his Cuban compatriot Felipe Orlando to a circle of artists associated with the recently formed Galería Prisse: young men who had become disillusioned with social realism and wished to open new lines of artistic discovery. He immediately took the group under his wing by offering several of them solo shows at the PAU Art Gallery, and chose Cuevas as the first of the young Mexicans to represent the new wave.6 The Cuevas exhibition of July-August 1954 was an unqualified success. Gómez Sicre wrote the short catalogue essay and arranged for extensive press coverage—Time magazine and The Washington Post were among the publications that printed significant reviews.7 What is more, all 39 of the featured drawings and watercolors were sold to important American collectors or to diplomats from Latin American countries, and Gómez Sicre himself selected two drawings for acquisition by the Museum of Modern Art of New York.

The show brilliantly launched Cuevas's career, signaling him as an ascendant figure in contemporary art, and from that point forward the artist tied his star to Gómez Sicre, who effectively managed his career for a half-dozen years, arranging shows in the U.S., Europe and Latin America, putting him in contact with gallery owners and dealers, writing on his art and encouraging others to do the same, while sending him on trips abroad, to Cuba, France, South America, Italy and Spain, where the attractive and well spoken, if still somewhat aloof, prodigy pleaded the cause of artistic freedom.8 Under Gómez Sicre's care, Cuevas's rise from obscurity to international fame was astonishingly fast. After the close of the PAU show, he stayed in Washington for about a month and then went to New York, where he remained till year's end. There he was introduced to the gallerist Phillip Bruno and to Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the illustrious director of the Museum of Modern Art. The following spring, he showed at the gallery of Edouard Loeb in Paris, at which time the first monograph on his work appeared—bearing the title La personalité de Cuevas, it was edited by Michel Brient and included texts by the Dadaist poet Philippe Soupault, the director of the Musée d'Art Moderne Jean Cassou, and the critics Horacio Flores Sánchez and Margarita Nelken.

The positive reception of Cuevas's art occurred at a juncture in the history of Mexican art when the hegemony of social realism was beginning to be seriously tested. In 1952 Rufino Tamayo resettled in the country after nearly twenty years living abroad, and in the same year Juan Soriano and Pedro Coronel returned from sojourns in Europe, enthusing local artists with their international perspectives and non-naturalistic styles. Also in 1952, the German émigré Mathias Goeritz moved to Mexico City from the outpost of Guadalajara and began the construction of the experimental gallery El Eco. Other sites for progressive tendencies were the Galería Prisse (1952-1954), where Cuevas began showing in 1953, and its successor Galería Proteo (1954-1961).9 Indeed Cuevas appeared on the scene precisely as tensions between non-conformists and the old guard were coming to a head in a dispute over the Salon of Mexican Visual Art (Salón de la Plástica Mexicana) of 1954-1955. At this show the organizers gave preference to Mexican School Painters and awarded prizes to social realists, prompting a rival exhibition which opened in March 1955 at Galería Proteo. Named International Confrontation of Experimental Art (Confrontación Internacional de Arte Experimental), and later called the First Salon of Free Art (Primer Salón de Arte Libre) or simply the Independent Salon (Salón Independiente), it was curated by Goeritz and featured eighteen native and foreign-born artists, including Cuevas, who had recently returned from New York and who became a leading voice in the critical test of wills elicited by the show.10

Gómez Sicre's backing of avant-garde artists in Mexico was calculated to take advantage of these initial cracks in the edifice of social realism. The year prior to his trip he had organized shows at PAU of José Clemente Orozco and Rufino Tamayo, and the previous year of Carlos Mérida: three mature artists who had strayed from the Mexican School and represented an early "counter-current" (Jorge Alberto Manrique's term) to realism. In the years immediately following his trip to Mexico, from 1954 to 1960, he fitted into the gallery schedule the aforementioned series of shows of younger artists, most of whom were associated with Galería Prisse and are identified today with the Ruptura movement.11 Cuevas was chosen to be the first artist represented in the series because Gómez Sicre considered him the arch-example of a new, individualistic and cosmopolitan spirit, and the subsequent management and promotion of his career was designed to encourage others of like tendency in Mexico and throughout the hemisphere.

Gómez Sicre also intervened in Cuevas's practice, by redirecting his attention away from life studies of street persons and the insane to great works of literary fiction. The first book he put into the artist's hands was a copy of Kafka, and in 1957, he arranged a six-month residency for Cuevas at the Philadelphia Museum School of Art, where he made a suite of drawings which would later be published in the volume The Worlds of Kafka and Cuevas, issued by the Philadelphia-based publisher Eugene Feldman.12 This is not to say, however, that Cuevas's literary interests stemmed entirely from his North American handler. Well before they met, the artist had shown an enthusiasm for European literature, which was fostered by Nelken and other exiles.13 But it was Gómez Sicre who saw the commercial opportunity of art tied to great books and anticipated the fructifying effect that works of literature would have on Cuevas's art. Additionally, Gómez Sicre, and Cuevas too, perceived a larger significance in the project, for it demonstrated that a Latin artist could contend with the masters of European fiction on the same plane, as a co-participant in world culture, and not from a timid and subordinate position; hence the publication was titled The Worlds of Kafka and Cuevas, implying equality of status between the two creators.14

We may pause for a moment to consider the style of the images that correspond to literary works. Beginning with the Kafka series, Cuevas's graphic technique and treatment of pictorial scenes evolved in stages until reaching a fully resolved manner around 1969, with the lithographs published in the suite Homage to Quevedo (fig. 4). When held against the earlier sketches from life, these "mature" works are seen to be constructed from graphic marks that are less fragile and attenuated; the figures are more intricately modeled and assume substantial form; the compositions are not so scattered as before but almost "classical" in balance and spacing (Cuevas referred to the lessons he drew from Fra Filippo Lippi and other Renaissance masters); and rather than scrawled onto the flat whiteness of the paper the subjects are set within dimmed cavities of notional space. The images are pictorially complete, formally composed, and visualize a fictive world that appears whole and self-sufficient.

Cuevas has always been attracted to cinema and theater, particularly to films with a surreal or oneiric quality and to the theater of the absurd, and the lurid environments of his later drawings resemble at times film or stage sets.15 They represent defined but unspecified locales, usually interiors, in which a figurative grouping may be invented and arranged freely, imaginatively, without the pressure of describing an actual place or illustrating a set narrative. Most of the environments are in fact so stripped down and cleansed of domestic bric-a-brac that they begin to resemble the antiseptic wards of a hospital or mental asylum, places that have continually haunted Cuevas, who is a self-confessed hypochondriac and frequent convalescent, and in this aspect they provide suitable contexts for his medico-artistic investigation of inner life.16 Or, in their darkness and vacuity they may suggest caves, a word rendered in Spanish as cuevas, reflecting the artist's patronymic, and thus designating spaces of his own domain—the sealed chambers of his personal fantasies; and they additionally bring to mind the numinous hollows where the high priests of ancient Mexico communed with their hoary gods and spirits. As postulated by one commentator, they situate Cuevas's pictorial imaginings within mankind's primeval abode: "the cavern, the prehistoric belly, the locale of origins and the reserve of phantasms, hell and paradise lost in an irreducible ambivalence."17

Confronting the Cactus Curtain

To his contemporaries Cuevas's art appeared as an open rebellion against the main current of Mexican art. The austere, direful images, drawn in black ink on white paper, controverted the idyllic charm and lush colorism of the Mexican School of Painting, which was then in full flower, and their introspective character ran against the social mission of art as defined by the muralists.18 The intimacy of the drawings, the individuality of their gestural marks, the idiosyncratic treatment of their hermetic subjects, whose purport is accountable only to the artist's private satisfaction and to no collective interest, the apparent lawlessness of the washes and vermiculated hatch marks, all of this appeared to abjure the oath of social responsibility which was not only the central tenet of the mural movement but an article of faith expected of all citizens in a country striving to affirm its sovereignty and achieve the communitarian goals of the Revolution. Cuevas's quirky, cryptic, "apolitical" drawings, accompanied by the insults he threw at the muralists and his declarations of artistic freedom, were taken quite seriously. His open heresy against social art and the revolutionary ideology presented a tangible threat to the artistic establishment and bestirred the ire of its supporters.

Cuevas began his famous polemic with muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros in an interview of August 1954 for Time magazine, in which he showed the youthful temerity to mock the mural painters, and the subsequent war of words between Cuevas and his friends and Siqueiros and his clique continued deep into the 1960s, and even spilled into the following decade.19 Siqueiros stood as champion of social art against modernist abstraction and "art for art's sake," which he believed was a bourgeois invention dependent on the capitalist market, as well as an instrument of imperialism exported to the far corners of the earth to impress a uniform way of life on all peoples while suppressing any competing nationalism or social philosophy.20 As evidence of this he pointed to the crucial support for modernism by non-nationals living in Mexico, including the community of Spanish exiles, and the still more egregious interference of U.S. officials, like Gómez Sicre, in the cultural affairs of the country. To rebuff this capitalist-imperialist conspiracy, he helped organize the National Front of Visual Arts (Frente Nacional de Artes Plásticas) in 1952, and later, in 1959, his allies Juan O'Gorman, Carlos Orozco Romero and Raúl Anguiano founded the Union of Painters, Sculptors and Printmakers of Mexico (Unión de Pintores, Escultores y Grabadores de México) to preserve "art at the service of the people" (arte al servicio del pueblo).21

Cuevas, with lance lowered on the tilting yard, upheld the banner of artistic freedom, charging that the quality and variety of expression had been artificially constrained by a narrow and overbearing political agenda, as plainly indicated by the title of Siqueiros's 1945 publication No hay más ruta que la nuestra ("There is no other route than ours"). In a caricature of Siqueiros from 1958 (fig. 5)—drawn in Washington, D.C., and attached to a letter addressed to Gómez Sicre which mentions the dissemination of some polemical writings by Cuevas to Latin American publishers—the newcomer portrayed his rival as the last-standing monster of muralism, still chanting the old refrain, "There is no other route than ours." As Siqueiros propounded a political or socialist humanism (which I have elsewhere described as his "revolutionary humanism"), based on a structure of shared values and a program of collective action, Cuevas represented the outlook of neo-humanism, associated with European existentialism and grounded in the dignity of the individual and his right to free thought and expression.22

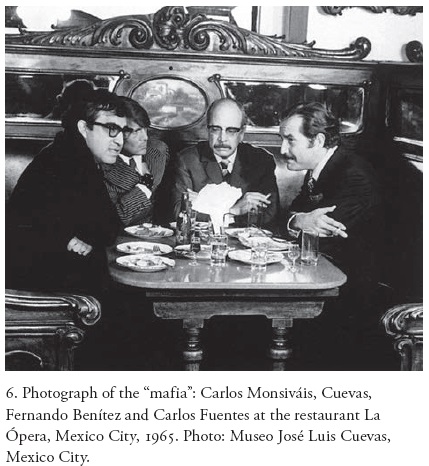

The controversy with Siqueiros soon made Cuevas a pivotal figure in the cultural politics of the 1950s and forced him to become an articulate polemicist, writer, lecturer, interviewee, who ever since has been constantly in the public eye, and under public scrutiny. Through the novelist Carlos Fuentes, he was introduced to Fernando Benítez, publisher of México en la Cultura, the cultural supplement of the newspaper Novedades, to which he began submitting essays of various sort, some polemical in nature and others of broad cultural interest, and later he wrote regular columns for the dailies Excélsior and El Universal.23 In this way he developed into a talented writer and entered into Mexico's literary community, which was then beginning a new era of cosmopolitanism, as seen in the pages of the Revista Mexicana de Literatura (1955-1965), which Fuentes directed in its early period.24 Similarly, Cuevas consorted with authors from outside Mexico, among them Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Julio Cortázar, and as they rose to international fame with the Latin American literary "boom" of the 1960s, so his aura grew ever brighter.25 He shared with them a broad view of international culture and an experimental turn of mind, and could depend on them to join his campaign against official art and defend him from hostile criticism, as did Fuentes, Xirau, Benítez, Juan García Ponce, José Emilio Pacheco and Octavio Paz on innumerable occasions. In response, Cuevas's foes extended their reproach to the entire consortium of Mexican artists and authors to whom he was attached, baptizing them "the mafia" and attributing to them a collusive scheme to diminish the national culture (fig. 6).

Cuevas's most widely read critique of the art establishment was the fictionalized, but largely autobiographical, tale of 1958, slyly titled "The Cactus Curtain" (La cortina de nopal) to equate the cultural regime in Mexico with the Soviet tyranny that had descended across Europe.26 The story centers on the character of Juan, a young artist whose creative spark is doused by a regulative system of art patronage and an oppressive social ethic which award mediocrity and depreciate originality and true talent. In this and other writings, Cuevas exposed the parochialism, exacerbated nationalism and sterile group-think plaguing Mexican art—as he saw the conditions prevailing at the time—while espousing a wider, more tolerant, international perspective, with which artists might reach out to foreign sources, as he had done. "What I want in my country's art are broad highways leading out to the rest of the world, rather than narrow trails connecting one adobe village with another," he said.27

Cuevas undertook his first visit to South America in 1958, shortly after the publication of the "Cactus Curtain" article. With financial support from PAU, he made a circuit of five countries (Colombia, Peru, Chile, Uruguay and Argentina) and exhibited his art in Caracas and Lima.28 However, hardly had he disembarked in Venezuela than he met a salvo of criticism from the social realists of that country, who were faithful admirers of Mexican muralism. In an interview with the newspaper El Nacional (Caracas) he pronounced against the muralists and South American painters of indigenous subjects, such as the adored Oswaldo Guayasamín, thereby inciting further fury and causing a rabble of artists and critics to block the doors of the gallery showing his art.29 The controversy followed him to Lima, where he responded with an inflammatory lecture in defense of free art.

Similar heat awaited him the following year when he traveled to Brazil and Argentina. This journey took him to São Paulo in the company of José Gómez Sicre and artists Armando Morales (from Nicaragua), Alejandro Otero (from Venezuela) and Modesto Cuixart (from Spain), who, along with Cuevas, were presenting work at the Fifth Biennial of Modern Art. By then the essay on the Cactus Curtain had become well known, and—as a consequence of its notoriety and of the recognition he received by winning first prize for drawing at the Biennial—Cuevas found himself widely acclaimed, and condemned, as one of Latin America's prime exponents of progressive art, even though he had only recently turned 26 years of age. A residence of three months in Buenos Aires was especially rewarding. There he befriended the authors Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Guillermo de Torre, Rafael Alberti, Manuel Mujica Láinez, and Jorge Romero Brest, all of whom praised his art in print. He exhibited at Galería Bonino—the city's main venue for modern art—and delivered several lectures, including one for the Asociación Ver y Estimar, founded by the eminent critic Romero Brest. As before, his defiant words attracted vehement protest in the popular press.30

The body of drawings and watercolors that Cuevas showed at São Paulo and Buenos Aires included a selection from the series Funeral of a Dictator (Funerales de un dictador), which he had begun in New York, and elements of which had earlier been presented in Caracas and Lima and in the United States.31 The series was inspired by a photograph of the 1875 funeral of Ecuadorian tyrant Gabriel García Moreno (fig. 7), which apparently Gómez Sicre had lent to Cuevas, and which represented the ruler's embalmed body sitting stiffly on the presidential throne in Quito Cathedral and flanked by a lugubrious guard of grenadiers. The bulky and swollen figures in this and other drawings from the series were based on the cubic shapes of Pre-Columbian art, which enhanced the universality of the theme of dreadful and petrified tyranny (fig. 8).32 The images were not specifically political in any partisan sense and referenced no particular governor or regime. They rather evoked the sloth, cruelty and wretchedness of despots or of oppressive systems of rule wherever they may be found, though most acutely with Latin American dictatorship in mind. As Cuevas explained with reference to the seminal source photograph: "I saw [the display of García Moreno's body] as something monstrous, an act, indeed, of 'Black Spain' in America. I began to work on the theme, and the sketch in gouache that appeared in Américas [the monthly publication of PAU] represents the most objective aspect of the series Funeral of a Dictator (Funerales de un dictador: verdugos y torturados). Afterward I tried to include all possible aspects of that idea: torture, sham, informers, subordinates, cringers, mourners, and so on. With that abominable funeral I wished to condemn all dictatorships of all times as the most intolerable indignity human beings can stoop to."33

It may be recalled that when these drawings were first presented in Caracas, Venezuela, that country had just rid itself of the military government of Marco Pérez Jiménez, and the images, sent south at the suggestion of Rómulo Betancourt, the newly elected President who had communicated his wishes to Cuevas at a reception in New York, must have struck viewers as a pointed critique of the defunct regime.34 However, as indicated in the quotation above, Cuevas hoped to render through the series a compendiated portrait of tyranny in its most generic form. In a later interview he said that the dictator might even be associated with Richard Nixon, for example—a thought which had perhaps crossed his mind already in 1958, the year of Vice-President Nixon's disastrous tour of Latin America, during which unruly demonstrators in Lima and Caracas, angered by US intervention in Latin America and its coddling of autocrats, pelted Nixon with insults and stones.35

It was around 1959 that critics began to notice the influence of Cuevas's drawing style and penetrating study of the human condition on other Latin artists, or if not a clearly direct influence, then at least a shared propensity in artistic practice.36 Cuevas himself observed that his exhibition and lecture in Buenos Aires had a palpable effect on Argentine artists, particularly Alberto Greco, and indeed one finds correspondences between Cuevas's expressive draftsmanship and the gesturalism of members of the Otra Figuración group, who first exhibited together in 1961 at the Peuser Gallery of Buenos Aires.37 These artists sipped from various international sources— De Kooning, Spanish Informalism, CoBrA—and also, it seems, from Cuevas, whose graphic style was admired by several in the group (namely, Luis Felipe Noé, Rómulo Macció, Ernesto Deira and Jorge de la Vega). Indeed Cuevas's art came to be admired all around South America—by such likes as the Brazilian Marcelo Grassman, the Venezuelan Jacobo Borges, the Peruvian Fernando de Szyszlo, and the Colombians Leonel Góngora, Alejandro Obregón, Enrique Grau and Fernando Botero—leading some critics of the early sixties to speak of a wave of "cuevismo" spreading over the continent.38

Cuevas exerted a still stronger influence on the Mexican movement Nueva Presencia (1961-1963), also known as Interiorismo, and was identified in the brochure for the group's inaugural show of 1961 as its chief member and inspiring force.39 In fact, though, he exhibited rarely with Nueva Presencia and remained more impressed by his South American disciples; he later distanced himself from the artists of the circle and wrote derisively about the quality of their work.40

These artistic movements in Argentina and Mexico were local expressions of an enthusiasm for the human subject that was felt globally in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and Cuevas may be viewed within this large panorama. Commonalities may be found between his work and Art Brut, for example, or even more prominently between his work and that of the Spanish Informalists, though in this instance the precise line of influence is hard to establish. Certainly Cuevas was aware of the experimental practice of Spaniards in the El Paso and Dau al Set crowds. He got to know Modesto Cuixart in 1959, and would later befriend Antonio Saura and Manolo Millares. Indeed, one may fairly imagine that the phrases in the manifesto of the El Paso artists, calling for the salvation of the individual and radical liberty, might have been uttered by Cuevas himself, and the discussion of artistic gesture in Saura's book Espacio y gesto could well have been illustrated by Cuevas's loose and agitated drawings.41 Parallels may also be established with artists in the United States, such as Leonard Baskin and Ben Shahn, and it seems that ideas originally proposed by Cuevas were picked up by North American critics and reappear, among other places, in Seldon Rodman's influential publication of 1960, The Insiders (from which the Mexican Interioristas derived their name).42

On entering the wider arena of international art and culture, Cuevas turned his back on the parochialism of the Mexican scene, with its essentializing notion of Mexicanness (mexicanidad) and restrictive demand for social responsibility. At home he continued to be defended by writers like Nelken, Fuentes and Paz, while in South America he found a forceful and energetic ally in the critic Marta Traba (fig. 9). She seems to have had the pulse of his artistic temperament, and in one place he described her as "my dearest friend and critic of my work."43 Born and raised in Buenos Aires, Traba spent the crucial years 1958-1969 in Bogotá, Colombia, as professor of art history and director of the Museo de Arte Moderno, and in that period she developed into the most vociferous proponent of independent art in Latin America.44 Like Cuevas, she traveled constantly around the hemisphere, and also like him she received support from OAS (Gómez Sicre was a close friend and frequent collaborator) and from United States corporations and their Latin American subsidiaries, despite her avowed leftism.45 Traba spoke about a "culture of resistance" which opposed the anonymity and heartless rationalism of industrial society and the sterility of authoritarian systems, and she stood up for figuration against geometrical abstraction, which she saw as another symptom of modern dehumanization. In several books and articles she proclaimed Cuevas as a brilliant exemplar of figurative art, and described with much sensitivity and philosophical circumspection his unique insight into the human condition.46 Her most important publications sought to define the artistic tendencies that were then extending across Latin America, and in this critical project—one of the first sustained narratives of contemporary Latin art—Cuevas was given a central place as instigator of what Traba called "the leap into the void" (el salto al vacío) by the most advanced and daring artists.

Cuevas and the Inter-American System

Cuevas was no friend of Francoist Spain. In 1961 he presented in the Roman gallery Il Obelisco the series The Spain of Franco (La España de Franco) (fig. 10), which satirized the moribund dictatorship (Cuevas wrote, "these drawings represented a beast who dies after suffering successive mutilations"), and one image in particular, a triptych titled The Fall of Francisco Franco, portraying the assassination of a tyrant, so offended the Spanish embassy in Rome that Cuevas's visa to Spain was revoked.47 Nevertheless, two years later he achieved admission into the country—from the United States—where he prepared the series From the Diaries of Spain (De los diarios de España). But when invited to participate in the Hispano-American Biennial "Art of America and Spain" (Bienal Hispanoamericana "Arte de América y España"), organized by Luis González Robles for the Instituto de Cultura Hispánica under the aegis of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and supposedly assured by the organizers that he would win the prize for drawing, he declined to enter his art in protest against Franco's hold on power, and afterwards laid out his position in an interview with the Madrid-based publication ABC.48

It was not Spain herself that Cuevas rejected. On the contrary, he was then and is today deeply enamored of the country and its literature, customs and artistic traditions; over the years he has periodically returned there for extended sojourns, and has dedicated nine separate series of prints and drawings to Iberian themes.49 Yet Spain's tinseled glory has no particular allure. He is drawn rather to the image of "dark Spain," of the ravenous, hierarchical, credulous, brutish Spain, the malformed entity described in the literature of Unamuno and Valle Inclán. He once stated: "The Spain that conquered me is, of course, that of somber hues, the black Spain of [the painter] Gutiérrez Solana, that of the Rastro and of the Calle Echegaray [areas infested with prostitutes], grotesque and Goyesque Spain."50 Cuevas shows no more appreciation for an artificially exalted image of peninsular civilization than for the reductive mexicanidad propagated by the officialdom at home.51 Indeed he finds congruence between the rigidities of Spanish society and the stultifying hierarchies of his own country, and accepts Black Spain as part of his own inheritance, such that his critical images of Spain may be seen as reflections on Mexico and on his own self as a bastard son of the metropolis.

It is perhaps a sign of shifting allegiances that once Cuevas had formally rebuffed González Robles and publicly declared his anti-Francoist views, he returned not to Mexico but to the United States, and exhibited his recent work in a second solo show at the Pan American Union. Does this physical movement of the artist from Madrid to Washington indicate a redirection of sympathies from Spain to the United States? Does it reflect a transition in Cuevas and the artists and intellectuals of his generation from a loose adherence to transatlantic Hispanism—mainly understood in the liberal, humanistic sense as pronounced by Nelken and other exiles—to the acceptance of a new cosmopolitanism led by the US? And is there a political dimension to this realignment? Does the choice bear witness to a reordering of cultural influence in the Americas, paralleling the political concession that Franco's government made to the United States, in which North American supremacy in the Western hemisphere was accepted in exchange for diplomatic recognition and the integration of Spain into the Western alliance, as described by the historian José Luis Rubio Cardón?52

Certainly there had existed for some time a concerted effort by the US government and associated institutions (OAS, Museum of Modern Art, Rockefeller Foundation, Fulbright Program, etc.) to curry favor with the intelligentsia of Latin America and bring it into alignment with North American political interests and values.53 This began with the Good Neighbor Policy of the Roosevelt administration and the creation of a network of multilateral organizations in what is known as the Inter-American System (IAS). The ultimate justification for the system—which extended over all areas of social, economic, political and cultural life—was collective hemispheric defense, first against Fascism and later against Communism, though underlying the arrangement was the older goal of unifying the entire hemisphere under North American leadership, in what is known as Pan Americanism.54

The Organization of American States, founded in 1948 and operating from 1951, was the linchpin for the Inter-American System. The mandate of Gómez Sicre, director of the Visual Arts Section of PAU, was to use the resources at his disposal to foster amity and understanding among the nations and peoples of the hemisphere by encouraging frequent interchanges of artists and critics, by issuing publications on the arts, by lending support to the most promising and original creators of the region, by sponsoring exhibitions in the United States and abroad, and by advocating in miscellaneous ways for freedom of expression.55 With the financial resources and network of contacts of OAS behind him and by dint of his personal drive and intelligence, in the 1950s and early 60s he reigned as the most important North American critic and curator of Latin American Art.

Gómez Sicre is occasionally dismissed as a mere agent of US diplomacy, and the art he promoted as an instrument of Cold War politics, or even of North American imperialism.56 However this portrayal is quite unjustified. Although an opponent of Communism, he was an individual of refined sensibilities, respectful of artistic and critical independence, and one who had no wish to impose North American artistic styles on the diversified cultures of Latin America or to force the artists of the region into a condition of dependency on North American patronage and critical taste; although he did recognize the United States' role as "natural center" within an emergent hemispherical culture.57 He thought broadly about the region and its art, and hoped to encourage a lively and fertile dialogue among the artists and critics of the Latin countries. Marta Traba called him "the prime defender of a continental art and the first one capable of conceiving it panoramically, as a conjunction of sentiment..."58

Admittedly there exists an element of truth in the argument that Gómez Sicre, even if not a chest-thumping imperialist, served through his actions to place Latin artists under US cultural hegemony and weaken national art movements.59 Despite his broad mindedness he made no bones about his anti-Communism and openly wished to break social realism's hold on Latin American art, not only because he thought it restrained creativity but also for the reason that it tended to support leftist political movements. It may further be observed that Gómez Sicre held an important post at PAU and subscribed to the fundamental goals, which included the spread of political rights, freedom of expression and other tenets of democracy, and the development of an international civic society in the Americas. But the idea that anti-Communism, democracy and interdependence are simply code words for imperialism, as some have argued, or that OAS functioned merely as a tool of US foreign policy, are highly debatable positions, as is the inference that Gómez Sicre and Cuevas were obliging stooges of the North Americans in their grab for power.

One may rather set Cuevas within a web of institutions that took shape in the 1950s and promoted a hemispheric artistic culture, at the center of which sat Gómez Sicre, with tentacles on the many strings. For PAU was only one piece, albeit a crucial piece, within a consortium of institutions that contributed to the cultural unification of Latin America. Brought into the fold were numerous art galleries and museums spread around the hemisphere, beginning with the PAU Art Gallery, and extending to such institutions as the New York Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Fine Art at Houston, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Walker Art Center of Minneapolis, Museo de Arte Moderno of Bogotá, Instituto de Arte Contemporáneo of Lima, Taller Libre de Arte of Caracas, and in Buenos Aires the Galería Bonino, Instituto Torcuato Di Tella and Museo de Arte Moderno. In Mexico there were the private galleries Prisse and Proteo, plus those of Antonio Souza (est. 1956) and Juan Martín (est. 1961), the briefly lived El Eco, directed by Cuevas's close friend Mathias Goeritz, the Casa del Lago, and the Museo de Arte Moderno.60

Many of these institutions were wholly or partly independent of government, and beholden to private industry for financial support—IBM, General Electric, W. R. Grace & Co., Acero del Pacífico, Alcoa Steamship Company, and particularly the oil conglomerates, most of all Esso corporation (today's ExxonMobil) and its Latin American affiliates, were strong supporters of the modern art movement.61 The Rockefeller family, which controlled Esso and stood behind MoMA, was enormously influential. Nelson Rockefeller, in addition to being a patron and collector of Latin American art, was one of the key architects of the Inter-American System; and in 1965 David Rockefeller founded the Center for Inter-American Relations, New York, now operating as the Americas Society, which ran an important exhibition space.62 Philanthropic organizations (e.g. Guggenheim Foundation, American Council of Education) as well as universities and colleges in the United States and Latin America distributed grants to progressive artists, exhibited their work, and gave them employment—for example, Cuevas held solo shows at the Universidad de Costa Rica (1967), Museo Universitario of Mexico City (1970), and Museo de Arte Moderno attached to the Universidad de Bogotá (1973), taught for brief periods at the Philadelphia School of Art, San Jose State College (now University) and Fullerton College, was supported by the Ford Foundation in 1965, and received private grants for residencies in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Washington and New York.

Gómez Sicre, as one of the presiding figures in this hemispherical art system, together with Traba and Romero Brest, was often asked to organize exhibitions or sponsor meetings and exchanges, and gave special attention to a select number of artists from different countries whom he considered most representative of the new progressive spirit (besides Cuevas, others within this privileged circle were Fernando de Szyszlo of Peru, Alejandro Obregón of Colombia and Armando Morales of Nicaragua). Exhibitions curated or facilitated by him were circulated in the US and Latin America and often funded by private corporations.63 Among the larger shows of this type were the international competition sponsored by the Alcoa Steamship Company, with a series of local exhibitions in cities where the sponsor maintained port facilities, and culminating in an exhibition at the National Academy of Design, New York, in September 1955; the Gulf-Caribbean Art Exhibition, financed by the engineering firm of Brown & Root, Inc., which opened at the Museum of Fine Art, Houston, April-May 1956, and then traveled to several venues in the United States; the three American Biennials of Art (Bienales Americanas de Arte), 1962-66, underwritten by Industrias Kaiser Argentina and held in Córdoba, Argentina, the home base of the corporation, before being taken to the PAU Art Gallery in Washington, and from there to other U.S. sites;64 and the 1962 exhibition titled Three Thousand Years of Colombian Art (Tres Mil Años de Arte Colombiano), funded by the International Petroleum Company, and shown in Bogotá, Miami and Washington. However the most ambitious of these enterprises was the Salon of Young Artists (Salón de Artistas Jóvenes), 1964-1965, sponsored by the Esso companies of Latin America. This exhibition of artists under forty years of age from eighteen countries marked the 75th anniversary of the Inter-American System. The process of selection took place in two stages: the first involved local exhibitions and the awarding of national prizes, and the second a show of national prize-winners at PAU, in April-May 1965, and the bestowal of international awards. Over 300 artists participated in this "Inter-American event," as Gómez Sicre described it, and in the catalogue he affirmed the private stimulus behind the project: "Of singular significance was the fact that it was private industry—the capitalist initiative of a free world—that was thus seeking to foster the things of the spirit by an undertaking with broad cultural repercussions."65

Mexico's preliminary show was held at the Museo de Arte Moderno in early 1965, as Competition of Young Artists of Mexico (Concurso de Artistas Jóvenes de México), but more popularly called Salon Esso. Today most historians identify this show as marking the full arrival of avant-garde art in the country. However, at the time the event stirred up blistering controversy. To begin with, there was the charge of favoritism in the awarding of first prize to Fernando García Ponce, brother of one of the judges. But in fact no group appeared very satisfied with the exhibition. Leftists such as Raquel Tibol and Luis Arenal denounced the attention it gave to non-political artists, while conservatives such as Federico Cantú and Francisco Moreno Capdevila, along with Francisco Icaza of the Nueva Presencia group, bemoaned the display of non-representational art and the honoring of García Ponce, who was an abstractionist. Amid the almost palpable tension at the award ceremony, Cuevas impulsively yelled out that García Ponce was greater than Orozco, provoking a hostile group to surround him. "Go back to Washington, traitor!" (¡Lárgate a Washington, traidor!), "Sold to the OAS!" ( ¡Vendido a la OEA!), they screamed in his ear, as he and Icaza got into a pushing match. Soon after the incident, the journal Político issued an editorial portraying Cuevas and Gómez Sicre as unwitting agents of imperialism.66 This was not the first time that this charge had been leveled. Cuevas felt the sting of the same insult in earlier exchanges with Siqueiros and during visits to South America; and Gómez Sicre had been similarly condemned in 1959 by Celestino Gorostiza, head of the National Institute of Fine Arts (inba), who asked the government to investigate his activities "en contra de la pintura mexicana."67

At stake was an autonomous national art dedicated to the interests of the Mexican people, which for many of Cuevas's critics included the socialist program of the Revolution, itself under threat from a succession of pro-capitalist governments and conservative leaders. Thus the rebuke leveled at Cuevas and Gómez Sicre represented an attempt to hold onto a political ideal. But the tide of events was inexorably driving this ideal out to sea, as the revolutionary outlook and the social art it commanded became increasingly untenable under the pressures of modernization and internationalization. Although this process was clearly abetted by North American institutions operating under the requirements of Cold War politics, it is unlikely that Mexican isolationism in politics and the arts could have been sustained deeply into the late twentieth century even had there been no such direct and coordinated intervention.

Internationalism, independence and art of resistance

Access to modern means of transportation—particularly travel by air—helped artists transcend national boundaries (fig. 11). Gómez Sicre drew attention to the importance of travel, arguing that it put artists in contact with one another and opened new markets to them, so they could begin to pry themselves loose from governmental patronage. He further pointed to the complementary growth of public and private art institutions that fostered diversity, openness and cross-fertilization.68 Cuevas was exemplary in taking advantage of these opportunities. As we have seen, he traveled widely in Europe and the Americas and exhibited at a variety of sites. However he was by no means the only Latin artist to venture from his home base. Many members of the avant-garde, such as Botero, Ramírez Villamizar, Del Villar, Negret, Grau and Obregón, made frequent trips abroad. In the decade of the 1950s, Latin artists routinely traveled to the European art centers of Paris and Madrid, and to New York and other points in the United States.69 Just as significant was their circulation within their own region, which allowed them to share artistic and critical ideas peculiar to Latin America, and to form a Latin consciousness and a more positive self-estimation.70

Cuevas was well served by the art market and able to make a living by selling his art through commercial galleries, which freed him from reliance on governmental support. This gave him the liberty to say what he wanted, to criticize official institutions without putting his livelihood at risk, and to be the self-governed creator that the character Juan in the parable of the Cactus Curtain had set out to become.71

Ever the subject of controversy, he attracted criticism for this very independence and freedom of movement, and found himself unfairly accused of being an essentially foreign artist who had gained wealth and fame from external sources of patronage and had become demexicanized in character and art. While it is true that he prospered abroad as much as at home (for instance, his illustrated books from 1959 to 1972 were all published outside Mexico), he strenuously insisted on his Mexican roots and emphasized the local origins of his art, declaring in one interview: "While I paint, I am an eminently Mexican painter, and in my work there appears in an obsessive manner the personal mythology created as a result of my Mexican experiences."72

Fully Mexican in his style of life and personal investment in the local culture, Cuevas nonetheless felt a troubling ambivalence about his native land. Continuing in the same interview quoted above, he announced, "However, in addition, for me Mexico is a world of terror and of horror, and to give it life in this world I need the perspective of distance. Before the monster, I cry, I become agitated, but I don't work. Instead, from afar, I have the tranquility necessary to create."73 Mexico exercised an oppressive effect. There he felt under pressure, under scrutiny, assailed by hostile critics and required to live on the defensive—"Kafkahuamilpa" was his original epithet for the country's inquisitorial climate. As noted by Alaíde Foppa, in conversations with her he frequently alluded to Mexico as a source of frustration and torment: "Mexico suffocates me" (México me asfixia), "I can't tolerate this country" (Ya no tolero este país), "I feel closed in like on an island" (Me siento encerrado como en una isla), "I think I'll never return" (Pienso no volver)74 Further complicating this relationship were his physical maladies, for in Mexico City he suffered from the smog, altitude and changeable climate, making daily life a misery and prodding him to flee to a more salubrious locale. Yet Mexico was his inescapable home and point of origin, and the constant wellspring for his work. Though his art was one of fusion and appropriation and his imaginative worlds filled with characters from world literature and diverse streams of popular culture— Kafka and Rembrandt, the Marquis de Sade and Fatty Arbuckle cohabit in the vacant spaces of his drawings (fig. 12)—at root was a deep feeling for Mexican society and vivid memories of early experiences in the country; these were ever present no matter which subject he chose to illustrate.75

Much as Cuevas benefited from patrons and sponsors in the United States, he refused to assimilate to North American culture or conform to its artistictrends. Quite the opposite, he resisted actively and with characteristic pugnacity the totalizing and dominating discourse issued from the North. In 1959 he began a campaign against abstractionist tendencies imported into Mexico and Latin America, and urged artists of the South to develop a figurative art that would best represent their independent culture.76 In this desire to strengthen the Latin American voice, he allied himself with Traba's notion of a "culture of resistance," which opposed equally the parochialism of local taste and the homogenizing effect of global discourses.77 Traba argued for the development of authentic regional languages of art criticism, which can evade the reigning meta-language that originates in and is addressed to a non-Latin social context. And she asked artists to invent modes of representation that were original to the continent and suitable to the culture and experiences of the region. With these positions Cuevas was in full accord.78

The oddest thing about Cuevas's art is that it is extremely personal and introspective yet constantly touched by outer stimuli. The images are projections of private thoughts and by the same account reflections on a large range of sources, chiefly literary. The nodal point is located in the living consciousness of the artist, of course, which blends his own rich memories and moods with the thoughts, images and even the personalities of authors he reads; hence the fixation on his own biography and mental and physical processes, as evidenced in his immense archive of personal documents, in the photographs he has compulsively taken of himself on every day of his mature life, and in countless other eccentricities.79 Cuevas is frequently accused of narcissism. But this is a mistaken view which takes in only one side of his art, the self-reflective part, when in fact the work involves both a projection outward and a reception inward, in such a way that the imagery is suspended between selfhood and otherness, identity and non-identity, being and non-being.80

There are points of correspondence between Sartrean existentialism and Cuevas's aesthetic and political position, and in fact it sometimes seems he may have consciously modeled his actions on existentialist principles. For the French philosopher, consciousness has no fixed or absolute definition but arises from our individual encounter with the world about us. We become ourselves through what we do and what we apprehend, and the wider our field of experience the larger and deeper the dimension of our conscious being. And so we choose to be who we are, and our selfhood is necessarily constituted in the realm of freedom. To deny or avoid this freedom is to resign ourselves falsely to another will or principle and to pretend that our selfhood is not of our own making; it is, in Sartrean terms, an act of "bad faith." In agreement with these philosophical postulates, Cuevas maintained that it is the artist's duty to strive for authenticity, to repudiate "bad faith," and to enrich himself and his expression by exploring the world openly and profoundly.

Cuevas represented a neo-humanism that did not aspire to save humanity as did the social art of Siqueiros. He refused to work within the confines of any organized movement or interest group, and rarely entered into political discussions. Yet he interrogated the grand premises and collective thinking of ruling institutions in an incisive and comprehensive way. By exposing the fragility, weakness, and instability of human subjects, he put in doubt the ideals of personal virtue and social progress which stood behind the myth of Mexican greatness (La grandeza de México) and the national revolutionary project.81 Of course, he was not the only artist to contest the reigning systems of art patronage and the parochial values they clung to. In the same period, fellow Mexicans—Gironella, Corzas, Vlady—and artists from lands to the south— De Szyszlo, Grau, Negret—similarly took new directions. But he was one of the most forceful polemicists of his generation, one of the most fiercely independent creators, and one who moved adeptly through the institutions that supported alternative modes of expression; and for these reasons he became exemplary of a "new" type of artist and identified with a new cosmopolitanism in Latin art.

On one occasion Cuevas declared: "I am the one Mexican who fights for the affirmation of the 'I' in the present, not in the future. The Mexican doesn't like to speak in the first person, nor to look straight ahead. I live in the first person."82 This statement was both a declaration of independence and a positioning of the artist in relation to social conventions. Cuevas recognized only the sovereignty of the individual, and maintained the artist's prerogative to forge his own path, without surrendering to any ideology or social program, and without postponing or otherwise bracketing the search for authenticity in the name of the collective interest. In this respect his art is aligned with the "weak subject" proposed by the Italian philosophers Gianni Vattimo and Pier Aldo Rovatti, a subject who retreats from the "strong thought" of reason and ideology and throws off their transcendental signifiers, and instead applies himself to local and heterogeneous histories and adopts new, individual strategies to apprehend the world from a position of non-subordination.83

Cuevas was one of the principal authors of a de-centered Latin American artistic culture, which grew from the independent choices of creators who passed beyond the tissue of common knowledge and consensual politics (without however utterly erasing all forms of interpersonal, social and national affiliation).84 This culture rested on the principle of untrammeled freedom of expression, which extended even to the concept of hemispherical identity; as Cuevas said, the trail blazers of modern art "learned to escape Latin Americanism" and acceded to a realm of liberty in which each could act and create on his or her own terms, and, unbounded, explore, interrogate, and drink copiously from local and global sources.85

1. For relations between Spanish exiles and Mexican artists of Cuevas's generation, see Christopher Fulton, "En una tierra más allá: refugiados de la Guerra Civil y la estética del exilio," in Wilfredo Rincón García et al. (coords.), in Arte en tiempos de guerra, Madrid, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2009, pp. 343-353, [ Links ] and the same author's "El éxodo español y el arte moderno en México: la migración de un ideal humanista," Goya, no. 321, November-December 2007, pp. 365-382. [ Links ]

2. Cuevas frequently spoke of his relations with Spanish refugees; for example, in an interview with Javier Arnaldo, "Una conversación con José Luis Cuevas en Madrid," Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos, no. 575, May 1998, pp. 19-28, [ Links ] and in an interview with Silvia Cherem, Entre la historia y la memoria, Mexico City, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 2000, p. 213. [ Links ]

3. His friendship with Nelken is described in Arnaldo, "Una conversación." Nelken reviewed Cuevas's inaugural show at Galería Prisse in Revista Hoy (Mexico City), June 23, 1953; [ Links ] and his second show at Prisse in Excélsior (Mexico City), June 1954, [ Links ] reprinted in José Luis Cuevas, José Luis Cuevas: el ojo perdido de Dios, Mexico City, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, 1997, pp. 96-97, n. 10. [ Links ] Other Spaniards who wrote on this exhibition were Rafael Hernández and Matilde Mantecón, and a short note of praise was written by Jorge Juan Crespo de la Serna. Nelken also reviewed Cuevas's show at Galerie Edouard Loeb, Paris, in Diorama de la Cultura, supplement to the newspaper Excélsior (Mexico City), April 30, 1955, [ Links ] and the exhibition of his work at the São Paulo Biennial, in "Un Primer Premio Internacional para México," Excélsior (Mexico City), October 4, 1959. [ Links ] Clippings of these and other reviews by Nelken may be found in the Hemerografía, Centro de Documentación e Investigación Especializado Octavio Paz, Museo José Luis Cuevas, Mexico City (henceforth Cuevas Archive). For Nelken, see Miguel Cabañas Bravo, "Margarita Nelken, una mujer ante el arte," in La mujer en el arte español, Madrid, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1997, pp. 463-484. [ Links ]

4. This observation is made by Rita Eder, Gironella, Mexico City, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, 1981, p. 23. [ Links ]

5. In 1954, soon before his departure for Washington, D.C., Cuevas was presented by the Catalan author Narcís Molins i Fàbrega with a book on the concentration camps in France, written by Molins and illustrated by Bartolí, as recounted in José Luis Cuevas, Gato macho, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1994, p. 77. [ Links ] The book is considered a classic work on the experience of the Spanish exiles; José Bartolí and Narcís Molins i Fábrega, Campos de concentración, 1939-194..., Mexico City, Iberia, 1944. [ Links ]

6. The encounter is described in José Luis Cuevas, "La breve historia de una generación arrinconada," México en la Cultura, supplement of Novedades (Mexico City), October 30, 1960, [ Links ] clipping in Cuevas Archive.

7. The reviews included Leslie Judd Portner, "Mexican's Work Sold Out," The Washington Post and Herald Tribune, August I, 1954 (www.washingtonpost.com); [ Links ] James Truitt (unsigned), "A Word with José Luis Cuevas," Américas (Washington, D.C., organ of PAU), vol. 6, no. II, November 1954, p. 15; [ Links ] by the same author (unsigned), "Art: A Vision of Life," Time, August 16, 1954 (www.time.com); [ Links ] Florence S. Berryman, "National Gets Two Stuarts; Mexican Artist," The Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.), July 24, 1954, [ Links ] clipping in Cuevas Archive; and unsigned review, "Exposición Cuevas," Boletín de Música y Artes Visuales (Washington, D.C., organ of PAU), no. 54, August 1954, pp. 33-34 (which mentions another review in the New York journal Visió [ Links ]n). It is sometimes said that Life magazine printed a review, but this is not true. Gómez Sicre further ensured that the show would be covered in South American publications; for example, Anonymous, "Nunca visto en Washington: un pintor latino de 21 años vendió todos sus cuadros," El Nacional (Caracas, Venezuela), August 22, 1954, [ Links ] clipping in Cuevas Archive. For the show, see Cuevas, Gato macho, pp. 78-82.

8. Cuevas's advocacy of artistic freedom is emphasized in José Gómez Sicre, introduction to José Luis Cuevas, Self-Portrait with Model, New York, Rizzoli, 1983, pp. 7-18. [ Links ] Cuevas was given a second solo show at PAU, held July 16-August 22, 1963; a retrospective of his prints and drawings was shown there on June 5-July 30, 1978, with lengthy catalogue essay by Gómez Sicre; and new work exhibited on April 2-17, 1982, in acknowledgment of his reception of the Premio Nacional de Bellas Artes de México.

9. The Galería Prisse welcomed foreign artists, including Vlady, Bartolí and Orlando, as well as Spanish writers and critics, such as Nelken and Hernández. The organizers of the gallery, Vlady, Héctor Xavier and Bartolí, were among the first to consider a new direction for Mexican art, according to Rita Eder, "La joven escuela de pintura mexicana: eclecticismo y modernidad," in Ruptura, 1952-1965, Mexico City, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, 1988, pp. 44-78. [ Links ]

10. For Cuevas's participation in the Salon and his role in the disputes of that year, see his Gato macho, pp. 87-89. He criticized the Salon and the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes in several places, including an interview with Luisa Mendoza, in Zócalo (Mexico City), December 13, 1954, [ Links ] clipping in Cuevas Archive.

11. The Mexican artists represented in this series of shows were Cuevas, July 14-August 16, 1954; Enrique Echeverría, July 6-August 6, 1955; Nacho López, August 28-October 4, 1956; Gilberto Aceves Navarro, September 19-October 13, 1958; Alberto Gironella, March 18-April 13, 1959; Lilia Carrillo and Manuel Felguérez, March 2-20, 1960, as recorded in Annick Sanjurjo (ed.), Contemporary Latin American Artists: Exhibitions at the Organization of American States, 2 vols., Lanham, Md., The Scarecrow Press, 1993 and 1997. [ Links ] For the Ruptura movement, see Rita Eder, "La joven escuela," and her "Las artes visuales en México de 1910 a 1985," in México, setenta y cinco años de Revolución, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1988, pp. 335-358; [ Links ] Teresa del Conde, "La aparición de la ruptura," in Un siglo de arte mexicano, 1900-2000, Mexico City, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes/Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1999, pp. 187-212; [ Links ] Romero Keith Delmari, Tiempos de Ruptura: Juan Martín y sus pintores, Mexico City, Landucci, 2000. [ Links ] The term "Ruptura" as a designation for the group did not come into common use until the 1980s, although as early as 1961 it was employed to denote the modernists' break with social art by Luis Cardoza y Aragón, "Pintura activa" (1961), in Ruptura, 1952-1965, Mexico City, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, 1988, pp. 1523. [ Links ] The existential interests and tendencies of the group are explored in Juan García Ponce, Nueve pintores mexicanos, Mexico City, Era, 1968. [ Links ]

12. The Worlds of Kafka and Cuevas, ed. and designed by Louis R. Glessmann and Eugene Feldman, texts by Franz Kafka, Max Brod and Rollo May, introduction by José Gómez Sicre, Philadelphia, Falcon Press, 1959. [ Links ]

13. Kafka, Dostoyevsky, Beckett, Sartre, Ionesco, Unamuno, Quevedo, Rulfo, Borges and Paz are some of the authors that captured Cuevas's interest. Several of these, particularly Kafka, Dostoyevsky and Unamuno, were popular among Mexican intellectuals from the circle of José Gaos, including Cuevas's close friend Ramón Xirau.

14. Cuevas, quoted in Héctor Ayala, "José Luis Cuevas a los 50 años: tiempo de recordar/I," El Semanario, cultural supplement of Novedades (Mexico City), vol. 2, no. 97, February 26, 1984, p. 4: "Nunca fui extranjerista, [ Links ] en ningún momento sufrí la tentación de querer ser cosmopolita por mi obra, ni entregarme a las modas impuestas por otros pintores o del centro de consumo... Creo que este libro [The Worlds of Kafka and Cuevas] es otro manifesto, pues muestra que un mexicano también puede observar la obra de un artista universal y aproximarse a él sin complejos provincianos." The significance of the pairing is also noted by Fernando de Szyszlo, "Imágenes para Kafka," El Comercio (Lima), February 1960, republished in Cuevas, José Luis Cuevas, pp. 97-99, [ Links ] and by Marta Traba, "Los mundos de Kafka y Cuevas," Semana (Bogotá), June 30, 1960, republished in Cuevas, José Luis Cuevas, pp. 103-105. [ Links ]

15. As described by Cuevas in an interview with César Benítez and Elizabeth Salgado, "Soledad, eroticismo y libertad en la obra de José Luis Cuevas: un mexicano universal," Imprenta (Mexico City), vol. 4, no. 14, March-April 2000, pp. 3-7. [ Links ]

16. In 1961 Cuevas visited the insane asylum of the Hôpital de la Charité de Charenton, France, and did a series of drawings and prints that imaginatively placed the Marquis de Sade in that space, for he recalled that Sade had been sent to an asylum and had organized theatrical performances with the patients as actors; he also set there Ambroise Tardieu, the nineteenth-century illustrator of the insane, as surrogate for himself.

17. Jean-Clarence Lambert, "Les maladies secrètes de José Luis Cuevas," Colóquio Artes, no. 71, December 1981, p. 45. [ Links ] Several others have noted this reflection of the artist's patronymic.

18. Cuevas, quoted in Alaíde Foppa, Confesiones de José Luis Cuevas, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1975, p. 212: "Y todaví [ Links ]a hay insensatos que me censuran por dibujar y pintar en blanco y negro, y me exigen que pinte con colores engañosos, con los colores de la mentira que tantos han usado para describir a México como país folklórico y alegre, mientras yo sólo veo drama y podredumbre."

19. Cuevas, quoted in anonymous, "Art: A Vision of Life," said that Rivera and Siqueiros "died several years ago and what is left are the politics and the public relations." In a later, unsigned article, "Art: New Directions in Mexico," Time, March 29, 1963 (www.time.com), [ Links ] he again attacked the muralists, calling Siqueiros "a comic dictator"; and he insulted Siqueiros's political program and artistic work in an interview with Jacobo Zabludovsky, "Cuevas habla de Orozco, de Diego, de Siqueiros, y por supuesto, de Cuevas [...] y dice: ¡El muralismo está en decadencia absoluta!," Siempre! (Mexico City), September 15, 1965, [ Links ] clipping in Cuevas Archive. Cuevas extended his criticism to the National Institute of Fine Arts (INBA) and other governmental institutions in December 1954, when interviewed by Luisa Mendoza for Zócalo (Mexico City), December 13, 1954, [ Links ] clipping in Cuevas Archive.

20. Most members of this group were non-partisan, though Bartolí and Vlady (son of Victor Serge, a prominent Russian Anarchist) possessed solid leftist credentials. However even they shied from Stalinism, which Siqueiros adhered to, and showed a preference for Trotsky, whom the muralist reviled.

21. Siqueiros, José Chávez Morado, Juan O'Gorman, Raquel Tibol, and Antonio Rodríguez identified modernism and abstract art as imperialist tools and faulted Cuevas for having become an agent of colonialism. A selection of arguments from this group was collected from a round-table discussion in 1958 and published as "Discusiones en el Frente Nacional de Artes Plásticas," in Raquel Tibol (ed.), Documentación sobre el arte mexicano, vol. 2, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1974, pp. 103-135. [ Links ]

22. In the early 1950s Emilio Uranga described the conflict between the social humanism of the Mexican Revolution and the bourgeois humanism that rejected the Revolution and its ideological program. For commentary on Cuevas's humanism, see Luis Rius Caso, "Entre lo monstruoso y lo humano: en torno a la fortuna crítica de José Luis Cuevas," in José Luis Cuevas, Mexico City, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2008, pp. 121-175, [ Links ] in which we read: "Su deformidad corresponde con la del nuevo hombre que hurga en su conciencia en busca de señales que le indiquen su verdadera identidad —su fondo y su forma— distinta y a la vez parecida a la del Hombre del que hereda tantas catástrofes íntimas e históricas, pero comprometida con la del hombre, su coetáneo, que se sacude el horror al encarnarlo y denunciarlo."

23. A selection of these pieces were republished in José Luis Cuevas, Cuevario, Mexico City, Editorial Grijalbo, 1973. [ Links ] Among the intellectuals who gathered around México en la Cultura were Luis Cardoza y Aragón, Jaime and Celia García Terrés, Juan Rulfo, Bárbara Jacobs, Augusto Monterroso, Iván Restrepo, Carlos Monsiváis, Zarina and Ricardo Martínez, Catalina Sierra, Manuel Buendía, José Emilio Pacheco, Paul Westheim, Jomi García Ascot, Juan García Ponce, Carlos Fuentes and José de la Colina.

24. Fuentes ran the journal with Emmanuel Carballo, and it was later headed by Tomás Segovia and Juan García Ponce.

25. Luis Rius Caso, "Entre lo monstruoso." Friendly commentaries by these writers are collected in Eduardo Cabrera (intro.), José Luis Cuevas visto por los escritores, 2 vols., Mexico City, Ediciones El Tucán de Virginia, 2000. [ Links ] For the contribution of these authors to the formation of a new Latin American culture, see Diana Sorensen, A Turbulent Decade Remembered: Scenes from the Latin American Sixties, Palo Alto, Stanford University Press, 2007. [ Links ]

26. The article was written as a letter sent from New York to Fernando Benítez, with the proposal that it should be published. It first appeared in México en la Cultura, cultural supplement of Novedades (Mexico City), April 8, 1958, [ Links ] and was reprinted in English with added foreword and afterword as "The Cactus Curtain: An Open Letter on Conformity in Mexican Art," Evergreen Review, vol. 2, no. 7, Winter 1959, pp. 111-120. [ Links ]

27. Cuevas, "The Cactus Curtain," p. 120.

28. The shows were organized by PAU and consisted of drawings from the series Funeral of a Dictator. They were held at the Galería de Arte Contemporáneo, Caracas, Venezuela, and Instituto de Arte Contemporáneo, Lima, Peru, October 20-31, 1958. The catalogue for the Lima exhibition was written by Fernando de Szyszlo. A summary of the trip is found in José Luis Cuevas, Cuevas por Cuevas, 2nd ed., Mexico City, Era, 1966, pp. 53-60. [ Links ]

29. Cuevas, quoted in Foppa, Confesiones, p. 144.

30. Ibidem, p. 148: "El cáncer del realismo socialista no había hecho grandes estragos en Argentina. Aun artistas políticamente comprometidos como Juan Carlos Castagnino y Berni, hacían un realismo bastante diferenciado del que practicaban, por ejemplo, Gómez Jaramillo, Acuña, Sabogal, Guayasamín y otros hijastros de la Escuela Mexicana. Por eso en Buenos Aires, mi batalla en favor de un arte neo-figurativo fue muy apasionada." His exhibition at Galería Bonino, Buenos Aires, 1959, was reviewed in La Nación by Ramón Gómez de la Serna and Manuel Mujica Láinez.

31. Drawings from the series were shown in Caracas, Lima, Buenos Aires, Pittsburgh (one large sheet, titled The Farse, at the Carnegie Institute's International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting), St. Louis, and Washington, before being presented in São Paulo. Some pieces were later exhibited at venues in Latin America, the United States and Europe.

32. Cuevas, quoted in Francisco Estrada Correa, "José Luis Cuevas," Posdata, vol. I, no. 1, November 1993, p. 18. [ Links ]

33. Cuevas, Letter to the editor, Américas (Washington, D.C.), vol. II, no. 10, October 1959, p. 43. [ Links ] In this passage he states that an Ecuadorian friend shared the photograph with him from an issue of Vistazo; though in Cuevas, Cuevario, p. 34, he says Gómez Sicre gave him the image.

34. The 1950's saw the fall of dictators: Juan Perón in Argentina (1955), Gustavo Rojas Pinilla in Colombia (1954), Marcos Pérez Jiménez in Venezuela (1958), Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic (assassinated 1961), and Fulgencio Batista in Cuba (1959, replaced by the Communist strongman Fidel Castro).

35. Cuevas, quoted by anonymous interviewer, "Habla José Luis Cuevas," Política, May 15, 1960, pp. 50-52, [ Links ] clipping in Cuevas Archive.

36. José Gómez Sicre, "Para la pintura, el mañana es hoy," Visión (New York), vol. 24, no. II, March 22, 1963, p. 21: "Junto con Tamayo, [ Links ] Cuevas es de las figuras latinoamericanas que mayor influencia han ejercido, no sólo en el arte del país y de América, sino en el de otros creadores extracontinentales."

37. Cuevas, Cuevario, pp. 134-135. For Otra Figuración, see Deira, Macció, Noé, de la Vega: 1961 Nueva Figuración 1991, Buenos Aires, Centro Cultural Recoleta, 1991. [ Links ] Otra Figuración (the name was inspired by the French art autre, coined in 1952 by critic and artist Michel Tapié) thrived 1961-1965, and was represented in a special exhibition at the Pan American Union in 1962, which assigned to the group the English title New Figuration. This nomenclature has been adopted by many Latin critics, who often refer to the movement as "Nueva Figuración." For the relationship between Otra Figuración and Cuevas, see Jacqueline Barnitz, "New Figuration, Pop, and Assemblage in the 1960s and 1970s," in Waldo Rasmussen (ed.), Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century, New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1993, pp. 122-135. [ Links ]

38. On the spread of Cuevas's influence in Latin America, see Luis Lastra, "José Luis Cuevas y el cuevismo," Excélsior (Mexico City), April 7, 1963, [ Links ] clipping in Cuevas Archive. At the Museo de Arte Moderno, Bogotá, 1964, Cuevas addressed his imitators in a lecture titled "El Cuevismo visto por Cuevas," and in a statement contained in Cuevas, José Luis Cuevas: el ojo perdido de Dios, pp. 161-162, he claimed that Botero began drawing fat people after having seen his work. Marta Traba, Dos décadas vulnerables en las artes latinoamericanas, 1950-1970, Mexico City, Siglo XXI, 1973, p. 76, [ Links ] says that Cuevas's influence produced a bloc of young artists who, around 1970, "harán del dibujo una bandera y consigna de rescate de la personalidad perdida."

39. Malkah Rabell, Los interioristas, Mexico City, Centro Deportivo Israelita, 1961; [ Links ] a copy of the brochure is kept in the Cuevas Archive. The organizers of Nueva Presencia were Arnold Belkin and Francisco Icaza, and the group included Mexicans and foreigners, including the Spaniards Rodríguez Luna, Messeguer and Moreno Capdevila. For the movement, see Shifra M. Goldman, Contemporary Mexican Painting in a Time of Change, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1981, [ Links ] and Antonio Rodríguez, Nueva Presencia: Los Interioristas, Mexico City, Club de Periodistas de México, 1962. [ Links ]

40. Cuevas separated himself from the Interioristas in an article titled, "José Luis Cuevas contra los interioristas," Excélsior (Mexico City), January 20, 1963, [ Links ] clipping in Cuevas Archive.

41. For the emergence of the Spanish avant-garde, see Julián Díaz Sánchez, El triunfo del Informalismo: la consideración de la pintura abstracta en la época de Franco, Madrid, Metáforas del Movimiento Moderno, 2000; [ Links ] Valeriano Bozal, "La imagen de la posguerra," in España: vanguardia artística y realidad social, 1936-1976, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1976, pp. 83-110; [ Links ] and Genoveva Tusell García, "La internacionalización del arte abstracto español: exposiciones oficiales en el exterior (1955-1965)," in Miguel Cabañas Bravo (ed.), El arte español fuera de España, Madrid, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2003, pp. 121-130. [ Links ] The influence of the Spanish avant-garde was strongly felt in Mexico in the early 1960s, as recollected by the artist Manuel Felguérez, quoted in Rita Eder, Gironella, Mexico City, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1981, pp. 43-44; [ Links ] cf. El Informalismo en México: arte abstracto no geométrico, Mexico City, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1980. [ Links ]

42. Selden Rodman, The Insiders: Rejection and Rediscovery of Man in the Arts of Our Time, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1960. [ Links ] Although this book does not mention Cuevas by name (it does make reference to Orozco and Siqueiros), its title seems to derive from a series of drawings that he exhibited in the David Herbert Gallery of New York, and it appears to be indebted to an earlier publication by Alton Parker Balder with some sentences taken word for word from what Cuevas had told him; cf. Cuevas, Cuevario, pp. 136-137. Luis Rius Caso, "Entre lo monstruoso," pp. 162-163, suggests that some of Rodman's ideas may have been taken from Nelken, including the crucial thesis about expressionism which Nelken developed with reference to Cuevas's art.

43. Cuevas, Gato macho, p. 532: "mi más querida amiga y crítica de mi obra." A touching eulogy to Traba is offered by Cuevas in Uno más uno (Mexico City), November 30, 1983, [ Links ] republished in Marta Traba, Bogotá, Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá, 1984, p. 397. [ Links ]