Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

versión impresa ISSN 0185-1276

An. Inst. Investig. Estét vol.29 no.91 Ciudad de México 2007

https://doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.2007.91.2250

Artículos

Bac on the Border

Emily Umberger

Arizona State University

Abstract

Although now on the Tohono O'odom reservation in the modern US Southwest, when the Franciscan church of San Xavier del Bac was built (1780-97), its location was the northern frontier of New Spain. From the outset the church stood out from other northern New Spanish missions in its elaborate decoration, and it still stands out because its contents remain intact, despite changes through time. This essay serves as an introduction to the church as a subject of art historical study. It highlights the following topics: the relationship of the Franciscan program to the Jesuit program that preceded it in an earlier church at the site, the original Franciscan arrangement of figures, style linkages among the sculptures and what they imply about the New Spanish workshop/s from which they must have been imported, the painters and plasterers who worked at the church itself, and the possibility of different readings of the program by the Spaniards who created it, succeeding religious who altered it, and generations of native congregations. In addition to documenting eighteenth-century Franciscan ideas, the church at Bac provides evidence seemingly not available elsewhere about the transferral of Jesuit properties and ideas after the order's expulsion from Spanish territories in 1767.

Resumen

A pesar de que actualmente se encuentra en la reserva de Tohono O'odom en el suroeste moderno de Estados Unidos, cuando la iglesia franciscana de San Xavier del Bac (1780-1797) fue construida, su ubicación era la frontera norte de la Nueva España. Desde el principio la iglesia sobresalió de las otras misiones del norte de la Nueva España por su elaborada decoración, y todavía se distingue porque su contenido ha permanecido intacto. Este ensayo es una introducción a la iglesia como sujeto de estudio de la historia del arte. Se resaltan los siguientes temas: la relación entre el programa franciscano con el jesuita que le precedió en una iglesia anterior en el emplazamiento, la disposición franciscana original de las figuras, los vínculos de estilo entre las esculturas y lo que significaban sobre el (los) taller (es) de la Nueva España de donde debieron haber sido importados; los pintores y enlucidores que trabajaron en la iglesia misma, y la posibilidad de distintas lecturas del programa creado por los españoles, sucesivos religiosos que lo alteraron, y generaciones de congregaciones autóctonas. Para documentar las ideas franciscanas del siglo XVIII, la iglesia de Bac proporciona evidencia, que aparentemente no está disponible en ningún otro lado, sobre la transferencia de propiedades e ideas jesuitas después de la expulsión de la orden de territorios españoles en 1767.

For Larry Fane

Increased attention in recent decades on the late eighteenth-century Franciscan mission church of San Xavier del Bac near present-day Tucson,1 Arizona, invites further study of many features of the structure (fig. 1). The great number and arrangement of its paintings and sculptures (fig. 2) indicate that its creators, friars Velderrain and Llorens, had ambitions for this church beyond others in the Arizona-Sonora chain. They were evidently inspired by structures further south for its forms and layout. In addition, they imported most of Bac's artworks and brought some artists to the church from the metropolitan centers of New Spain(now Mexico).2

There aremany factors to consider in the scholarly analysis of the church. Its original environment was very different fromthe present one. Although now on a reservation in the modern US Southwest, the church was built on the northern frontier of a Spanish viceroyalty by Franciscans at a mission site that had been founded by the Jesuit order a century earlier. There were two very different audiences from the outset and both changed greatly over time: the Franciscans and other observers who arranged and read its artworks in Euro-Christian ways; and the Native Americans, the recipients of teaching through these same images, whomight have read them differently. The published information on the church comes from the former, not the latter.

My focus is the Franciscan program during the church's Hispanic period, an eclectic mix of sculptures in different materials, techniques, and styles, linked by painted decorations. Blanks in our knowledge about its design introduce complex problems, which, although probably without definitive solutions, can be tackled. Many local studies of the corpus have been accomplished and the materials have been published or are in the process of being made available to researchers (see n. 1). These include archaeological reports, documents and photographs, studies of materials and manufacturing techniques, and observations of usage. On the basis of these resources, it is possible to use art historicalmethods to place the church within the broader context of the world of Spanish and New Spanish religious art. Even if the artists cannot be identified by name, their numbers and levels of skill may be hypothesized through study of the images themselves, and their places of training and later activities may be discovered from comparison with productions in particular areas of Mexico.

That the church's iconographic programwas designed in tandemwith the new structure is indicated by the first description of the church in the year of its inauguration, 1797. Mentioned are paintings on the walls, dome, and choir loft and thirty-two sculptures, meaningmost of those nowthere.3 The program focused on two sculptures that were moved from the earlier Jesuit structure at the site. These were joined by the majority of the remaining sculptures, whose style indicates that they must have been sent together as a commission from a single workshop or a group of connected workshops, presumably before the consecration of the church.Othersmay have arrived later fromthe same or different sources.With the addition of two final figures representing the parents of Christ sometime after 1848, the present ensemble appears to have been in place. These last figures were probably replacements for images of the same personages in the original program. Although the major sculptures that were focal points in the layout of 1797 have remained in the same places, anomalies in the locations of some of the small sculptures in peripheral niches indicate that changes weremade after that date. Principally, the addition or enlargement of the pulpit seems to have led to their rearrangement, and this happened probably sometime between the 1850s, when the church became a us possession, and the 1870s, whenthe first photographs of its interior were taken. After this, theAnglo period seems to have been characterized by onlyminor adjustments and repairs at the church, as it became increasingly a site of historical veneration and tourism.

In this essay, I will highlight the following topics: the relationship of the existing Franciscan program to the Jesuit program that preceded it, the sources and original arrangement of figures, style linkages among the large group of portable sculptures and what they imply about the hypothetical workshop/s, the artist/s who worked at the church itself, and the possibility of a different reading of the program by native audiences.

From the outset the Franciscan structure at Bac stood out from other northern New Spanish missions in its elaborate decoration, and it still stands out, because its contents were never destroyed or dispersed. The church's roof did not collapse, it was not seriously damaged by natural disasters, and members of the native congregations guarded its art during times of abandonment by religious. In addition, the international border that separated Bac from most of the other churches in the Arizona-Sonora mission chain protected it from Mexican post-Revolutionary activists who destroyed religious imagery in the 1930s.4 Theresult is that Bachas themost elaboratemissionary program from itstimeonthe northern frontier of theviceroyalty. In addition to documenting eighteenth-century Franciscan ideas, it provides evidence seemingly not available elsewhere about the transferal of Jesuit properties and ideas after the order's expulsion from Spanish territories in 1767.5

The Jesuit Mission at Bac

Long before the creation of the Franciscan church, Eusebio Francisco Kino (1645-1711) entered the area now covered by northern Sonora and southern Arizona. The year was 1687, near the end of the Habsburg era in Spain, and the region was called the Pimería Alta after itsNative American inhabitants, who were then as now categorized broadly as speakers of Piman languages. After establishing his headquarters at Dolores, the village of Cosari in Sonora, Kino went to Bac in 1692 and designated it as the site of missionary activities addressed to a local Papago group, the Sobaípuris who inhabited the ranchería (village) there. In later years other Papagos joined the Sobaípuris. Today the Sobaípuris are extinct, and the inhabitants of the SanXavier Reservation, created around the church in 1874, are descendants of these other, late arriving Papagos. They call themselves Tohono O'odom ("Desert People"), O'odom being a generic name used by Piman groups.

We know little of Jesuit conversion techniques at this site,6 and little of how the native congregations received the Jesuit ministry. No sermons are known, and there are few material remains and documents. Until 1756 the Jesuits had only modest buildings, a "house" for a friar and an open ramada serving as a church.Nevertheless, we know that Kino himself had ambitions for Bac. Having named it after his patron saint, Francis Xavier, he envisioned it as the site of a head church formissions yet to be founded in the territories he was exploring further north andwest. He never completed a significant ecclesiastical structure at Bac; nor was anymission founded in the areas further north. If his dream had been accomplished, however, Bacmight have replaced his headquarters at Dolores. 7

It was Alonso Espinosa who built the first true church in 1756, forty-five years after Kino's death. According to hypotheses made from archaeology at the site, this structure was a rectangular hall church, oriented with the chancel to the north and the entrance to the south. It had thick walls of sun-dried adobes and a flat roof made of wooden beams covered by earth. The appearance of the exterior is unknown, but an inventory written in 1768 mentions important aspects of the interior, notably three altar tables.8 The principal altar was devoted to Francis Xavier, the dedicatory saint; on it was featured his sculpted image dressed in real clothing. According to a document discovered by J. Augustine Donohue, Espinosa ordered it from Mexico City in 1759: "a head and hands of San Xavier with a body frame resembling the statue inVera Cruz."9 It is assumed by modern scholars that the dedicatory figure of the Franciscan church is the one listed in the inventory,10 given its closeness to the description (fig. 3).11

Other features of themain altar were a gilded wood tabernacle, paintings of Saint Joseph and the Virgin Mary in gilded frames, a small painting of the dedicatory saint, and four engravings on paper, whose subjects and framing are not mentioned. A 1763 document, also found by Donohue, gives further details about the two framed paintings: they were 1-3/4 varas (about five feet) in height, represented Saint Joseph and Our Lady of Refuge (a specific Marian type), and were "by the hand of Cubrera.12 Richard Ahlborn guesses that the reference is to Miguel Cabrera, the great painter active in Mexico City in the mid-eighteenth century.13 The paintings were probably by a follower. Given their size and subjects, they must have been half-length figures rather than heads or full-length figures.14 Nothing in the inventory or any other description indicates the presence of an altarpiece behind the altar. The mention of frames for these two paintings suggests, rather, that they were hung on the walls.

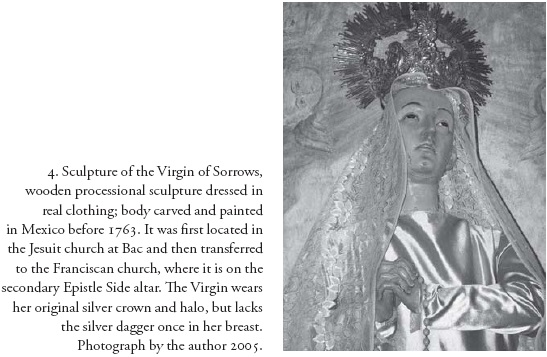

Of the two secondary altars peripheral to the main altar, one was devoted to the Virgin of Sorrows, the Dolores after whom Kino named his head town in Sonora. On this altar was another sculpture dressed in real clothing, imported from an unnamed location. The document of 1763 indicates its presence in the church by that time, and gives details on the form of the figure ("una cabeza, y manos de Nra Sra de los Dolores/ con la demas armazon para el cuerpo"). The description matches the present figure, which has removable hands, a dressed torso, and an armature for the lower body, like the Saint Francis Xavier figure. It is currently the focus of the Eastern/Epistle transept arm of the Franciscan church and the dedicatory figure of the altar at its end (fig. 4).15 Mentioned in both the 1763 and 1768 documents are the Virgin's appurtenances and articles of jewelry, mostly of silver, which recall similar objects in the wardrobes pertaining to Her in other Hispanic churches. The present sculpture still wears the silver halo-crown mentioned, and a slit in the chest indicates that a dagger, also listed but now gone, was once implanted there to symbolize the Virgin's pain.16 Whether her altar was on the west side of the main altar or on the east, as it is now, is not indicated by any document, but a location comparable to its present one would be logical.17

The 1768 inventory gives some information about the third altar in the Jesuit church. Associated with it were four prints on paper, a green curtain, and six metal wall candlesticks, but the subjects of the prints are not mentioned; nor is a sculpture. Given that the other two altars had major figures on them, the lack of a sculpture is surprising. Was Espinosa unable to obtain the image needed to complete the program? Or did someone take a sculpture from the church before the Franciscan arrival? In the present, Franciscan church, the niche directly above the altar is occupied by an image of Christ as Man of Sorrows, while an image that represents Saint Francis Xavier lies in a glass coffin or bier on the altar, incorrupt as his body was said to be in Goa, India. The Xavier sculpture is actually a reused processional Christ figure of unknown origin and date of arrival at Bac.18 It now represents the Jesuit dedicatory saint, but it is not mentioned in the Jesuit inventory, and it was probably not in the Jesuit church. As will be argued later on the basis of style, the standing Christ sculpture was made for the new Franciscan church, but it is most likely that a comparable sculpture of Christ at the time of the Passion existed or was anticipated in the earlier structure, to balance the Virgin of Sorrows.19 Given the north-south orientation of the church, the west side would have been on the proper right-hand of the main altar, the Gospel Side, from the point of view of God at the top of the main altarpiece or a cleric facing the congregation, and the east side would have been on the proper left-hand, the Epistle Side. According to Christian ideas, the Gospel Side had priority in multiple senses over the Epistle Side.20 If the Virgin of Sorrows were on the east side and a male figure were on the west, this would correspond with the rules of priority in terms of gender and time.

In 1767, only eleven years after the initiation of Espinosa's church, the Bourbon kings of Spain expelled the Jesuits from their territories all over the world, including the Arizona-Sonora mission chain, and the inventory, the church, and the church's contents were given to the Franciscan friar Francisco Hermenegildo Garcés who was sent to replace them there.21

The Franciscan Elaboration of the Jesuit Program22

Garcés ministered to the residents of Bac until his departure in 1779. He was replaced by Juan Bautista Velderrain, a friar who had been at the site since 1776 and who began construction of the Franciscan church at some time between 1780 and 1783. The building itself was probably finished by 1788. Velder-rain died in 1790, and was succeeded by Juan Bautista Llorens, a new arrival who directed the completion of the decoration. The church was inaugurated in 1797. The degree and nature of collaboration between Velderrain and Llorens is unknown. Franciscans who reported to administrators in Mexico to the south controlled the site until 1844, when they too left the area.23 Archaeology reveals that they buttressed the failing walls of the Jesuit structure, presumably while they were still using it as their primary church. Other evidences indicate that theydisassembled this older building before 1843 and reused the materials to build the wing of the cloister that was seen then and still abuts the Franciscan church.24

The period during which the Jesuit church was the Franciscans' primary religious structure was approximately twenty to thirty years in length — depending on when between 1788 and 1797 they began using the new one — and a number of similarities between the two indicate purposeful continuity. Perhaps ambitions similar to those of Father Kino when he founded the first mission there —the anticipation that this would be a center for further foundations to the north—were behind the later Franciscan structure. Although the new church was in the form of a cross, with a transept containing the secondary altars at the ends, it preserved the north-south orientation of the Jesuit structure. Thus, the Gospel Side remained to the west of the main altar and the Epistle Side to the east. The Franciscans also kept the dedications of the main altar and one of the side altars (possibly both), and transferred the sculptures of Saint Francis Xavier and the Virgin of Sorrows to the new church.

It seems, in fact, that the Franciscans kept the essence of the Jesuit program and elaborated on it. In addition to moving the secondary altars into the transept arms, they added a pair of tertiary altars at the junctures of the transept with the main body of the church. These altars were conceived as parts of their respective transept arm ensembles and, simultaneously, as a pair flanking the chancel with its main altar. The builders who worked for the Franciscans also pierced the walls above all altars with niches for full-length figures on two levels, framed the niches vertically with estípite columns, and topped them horizontally with cornices to create the effect of Baroque retablos (retables). The niches are of two sizes, a large size reserved for two levels of figures above each of the five altars, and a smaller size for flanking figures. To tie together the altars within the transepts, the retables behind them were extended to meet at bends in the walls. Above the cornices a third level of small niches was created for three-quarter-length figures in the case of the transepts and (decapitated) heads in the case of the main retable. A great fluted "shell" topped the main retable. Like the walls themselves, all cornices and estípites were made of bricks, which were shaped and then plastered and painted. Shaped and painted plaster swags, imitating patterned cloth, framed the niches. Plaster bases for candles were used instead of metal sconces on the walls. The ceilings of the nave, transept, and chancel were also sculpted and painted as shallow domes decorated with floral motifs or with faux folded cloth. The Franciscans also had figures in-the-round constructed of brick and plaster on the façade, above the retable cornices, and on walls and estípites in various places (e.g., angels of different ages). To fill the large niches they used the sculptures acquired from other churches or ordered from further south. Some of these were already dressed in garments made of wood or stiffened cloth, but most consisted of wooden bodies (like manikins), which were dressed in real clothing or plaster garments once they were at Bac.25

All parts of the church were covered with paintings. On the walls framed narrative and figural scenes participated in the iconographic program. The great dome over the crossing was decorated with painted images of saints and holy figures. Large and small flowers are among the textile patterns found in the clothing of two-dimensional figures and the swags over niches, as well as the clothed sculptures. Also noteworthy are elaborate interlaces, geometric hatching and net-like patterns, as well as the painted faces and bodies of attached sculptures. Gilding was applied to the estípites of the main retable and glazes were painted on silver surfaces flanking these supports.26 Imitating other objects and materials that were not attainable at Bac are a dado of faux tiles, faux marbling, and faux wooden doors, seat backs, and picture frames.

The interrelationships among these varied forms at the church need further study to indicate which paintings were integral to the installation of the 1790s and which not, and to determine the order of their placement and execution. Whatever the results, it is evident that the general plan of the iconographic program dates from that time, and the identities of the majority of sculpted and painted images were anticipated in the original plan, even if the actual objects were not present.

Primary among the Franciscans' physical retentions from the old church were the sculptures of Saint Francis Xavier and the Virgin of Sorrows. Both are processional figures and the present congregation uses them this way, removing them from their niches for rituals in other parts of the church or outside.27 One must conclude that they were part of the native Christianity introduced by the Jesuits after their arrival at Espinosa's church, and were retained for this reason as well as for their value as finely made sculptures.28

In addition to moving sculptures and paraphernalia from the Jesuit church into the new structure, the Franciscans replaced other art forms with their own versions. The most obvious of the replaced objects is the tabernacle (cupboard for the sacramental wine and bread) directly above the main altar. Being stylistically related to the other forms in the new church, it is easily recognizable as a replacement. The images of Joseph and Mary, the dedicatory saints of the tertiary altars on either side of the chancel, were replacements for the paintings of these two near the Jesuit main altar, but the history of these replacements is more complex. The 1797 description of the Franciscan church indicates that the tertiary altars intended for them were integral to the new ensemble, but if there were images on the altars, they are not mentioned. I do not doubt that the altars were intended for sculptures of Joseph and Mary, given the paintings in the Jesuit church, but what occupied them before the arrival of the present sculptures from Tumacácori, reportedly in 1848, is a mystery. There is one document pointing to a set of previous figures, a report by Cave Johnson Couts, saying that he saw a sculpture of Mary that was missing an arm two months before the arrival of the Tumacácori sculptures (something that could not be the case of the other two Marian representations in the church).29 It seems likely then that there were previous sculptures of Joseph and Mary that needed replacement.

Interesting in respect to these are the bases under the present figures. The base under Joseph is painted in a style seen elsewhere in the church, and there is no reason to suppose that it is from the Anglo Period. Moreover, outlines on the back of Mary's niche indicate the former presence there of a base of the same shape. This was partially dismantled to accommodate the present figure, seemingly because of the wooden block to which she is attached. The presence of bases from the Hispanic Period probably indicates that there was truly an earlier pair of sculptures, and that they too were too small for the niches they occupied. They must have been of the same relative size as the present sculptures, or perhaps somewhat larger. Without further study of the painting on the remaining base to ascertain when it was made, at this point all that can be concluded is that the change in location of these personages to the transept and the change in material from painted to sculpted forms were intended to highlight the parents of Christ with their own altars and, at the same time, to leave space around the main retable for a series of narrative murals detailing the events of Christ's birth.30

Further aspects of the Franciscan program mayhave corresponded to Jesuit ideas, but the Jesuit predecessors either were painted on the walls, and thus not mentioned in the inventories of portable objects, or were not represented visually in their church, but rather mentioned in sermons or other verbal forms. Specifically, I am thinking about the apostle figures that line the Franciscan nave. Although no such images are described in the Jesuit church, and style dictates that the present figures were made for the Franciscan church, the apostles must have been included in sermons and lessons. Evidence of their significance as models for the native congregation is the composition of an important native organization, the settlement's Feast Committee of twelve members.31 There is good reason to suppose that this organization's correspondence with the apostles may date from the Jesuit period. The Jesuits emphasized the link of their mission to the apostles in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Mexico.32 And, Kino himself, the Jesuit who founded the missions in the Pimería Alta, named a line of villages along the Gila River north of Bac for the apostles; the river itself he called the Río Grande de los Apóstoles.33

This naming was in anticipation of future missions, and although they were never founded, it indicates Kino's thinking in terms of an arrangement comparable to that of the figures in the Franciscan church.34 Thus, it is reasonable to think that the linking of the missionary activities on the northern frontier with the apostles, as evidenced in the sculptures in the Franciscan church, probably dates from the Jesuit period. When during this time the notion of the committee's comparability to the Apostles was incorporated into native thought is unknown. There were many gaps in Jesuit ministrations at the site, and much disruption by rebellious native groups, so the committee may have been changed or elaborated upon significantly as late as the building of the Espinosa church.

Among other possible Franciscan visualizations of Jesuit themes are the heads of the first Deacon Martyrs of the early Church, Saints Lawrence and Stephen, in oval frames flanking God above the main retable.35 As Lange and Ahlborn note, Lawrence and Stephen are represented with the Apostles, on the lower story of the façade of the great Jesuit church of Saint Francis Xavier at Tepotzotlan, Mexico, a church built at the same time as the Jesuit church at Bac. One might add that on the same façade there was a set of Virgin Martyrs, and that all of these early church figures are found at Bac, but in different locations.36 However, as in the case of the Apostle figures, in the Jesuit church these probably were presented in verbal narratives rather than in visual imagery.

Some convergences at Bac were probably a matter of like ideas that both Jesuits and Franciscans subscribed to —for instance, ideas about holy figures like the Virgin of Sorrows and the representatives of the early church; while others — for instance, the retention of the church's Jesuit dedicatory saint —were Jesuit only and, although possibly disagreeable to the Franciscans, they were deemed necessary because they were original to the church and had acquired local significance. In addition, the Franciscans would not have wanted to confuse the natives with ideological distinctions between different parties within the Spanish-Catholic world; nor would they have wanted to reveal conflicts. At Bac there is more evidence than so far revealed elsewhere in New Spain of an actual modification of a Jesuit program by a different order. Because the Franciscans brought the parts of their creation together with nearly invisible seams, it is difficult for us to untangle the threads —to analyze the histories, changes, and intentions behind the parts. This is especially true in places like the façade that show no signs of varied hands and sources. Yet comparisons of the motives on it with other churches and with the interior reveal the political conflicts involved in the change from Jesuits to Franciscans and, possibly, subtle messages addressed by the Franciscans to other non-natives.37

The Façade

We know nothing of the old Jesuit façade, but it would not have been like the Franciscan one, which emphasizes the relationship of that order to the holy figures of Christ and the Virgin as well as the Spanish Crown. The church has a retable-façade between two towers, and in this it resembles the multitude of parish churches that sprang up all over Mexico in the second half of the eighteenth century, except in its broader proportions. At the very top are the remains of a sculpture usually identified as the founder of the Franciscan Order, Saint Francis of Assisi. It now consists of a cone-shaped lower body, covered by "hard plaster" in the last quarter of the twentieth century, but some observers reportedly saw the remains of a Franciscan cord at the waist before it was covered. This is debated by Lange and Ahlborn, who argue for the figure's having been a representation of Saint Francis Xavier, the dedicatory saint. Their questioning of the identity of the figure is legitimate but the problem remains unresolved, due to the present state of the image.38 Saint Francis Xavier is the dedicatory saint, and he is highlighted on the interior main retable. However, the church is Franciscan and Francis of Assisi is also represented by a major sculpture inside, above Christ over the Gospel transept altar. In a Mexican church the dedicatory saint is generally found on both the façade and the main retable; at Bac this may or may not have been the case. Whoever the figure is, the insignia below him is definitely Franciscan. So, although the Franciscans did not change the dedication of the church, they put their insignia in prominent places and their own founder in at least one.

Other than this possible irregularity, the façade is like its Mexican contemporaries in announcing the devotions that were explicated on the interior, those to Christ and the Virgin.39 These references are in the form of symbolic reliefs combining their monograms with plant and animal metaphors rather than using figurative sculptures. The exclusion of figurative representations of Christ's death on the façade is understandable. The Franciscans had learned in the sixteenth century that the Crucifixion could be misunderstood by new converts and unconverted natives as a form of justifiable violence.40 It was safer to represent the ideas symbolically with the monograms of Christ and the Virgin surrounded by grape vines standing for Christ's blood transformed into the wine of the Eucharist. Although the insignia of Christ is very like the emblem of the Jesuit order (IHS above three nails and surmounted by a cross), in a Jesuit composition it would have been alone and centrally located, whereas here it forms a pair with the Virgin's name and together they flank a symbol of the Franciscan Third Order. This latter symbol, the crossed arms of Christ and Francis of Assisi nailed to the crucifix (an image that would be difficult to read by an uninitiated person), refers to the fact that Francis of Assisi bore the wounds of crucifixion also — uniting him with Christ in a relationship that was much closer than that of any Jesuit to Christ.

Another Franciscan sign that underlines this relationship is the cord belt. Introduced within the frame around the Franciscan symbol, it is repeated in a larger sculpted version running below the cornice of the second story. On the inside a similar sculpted rope forms part of the cornice and encompasses the whole interior, with its ends hanging on either side of the dedicatory figure on the main altar. The cross shape of the church traditionally was meant to embody Christ on the Cross, but the interior rope at Bac emphasizes the building's conflation of the body of Francis of Assisi and that of Christ, just as the symbol on the façade indicates the saint's identification with the holy figure.

On the façade the Franciscans linked themselves to the rulers of Spain as well, through emblems from the imperial coat-of-arms. Relieves of rampant lions stand for the kingdom of Leon and the actual towers of the church may stand for the castles of the kingdom of Castile.41 The lions differ from the Spanish coat of arms in holding plants, probably sheaves of wheat representing Christ's body transformed into the Eucharistic wafer, just as the vines refer to His blood. The inclusion of Franciscan symbols on a façade was not unusual in eighteenth-century Mexico,42 but royal symbols were,43 and the purpose was probably political. They were a reminder that the same Spanish dynasty that had ousted the Jesuits sponsored the Franciscan take-over. In fact, since the Jesuits had earlier wrested control of religious life in Central Mexico from the Franciscans, this inclusion of royal symbols on the upper façade may be interpreted as a statement of Franciscan triumph addressed to other Europeans.

In contrast to the more abstract treatment of the upper façade, the lower façade was to be understood in human terms, and its message was less political and more comprehensible to the local congregation. Its organization of niches within a grid of estípites and cornices is very like the interior retables, and figural sculptures likewise occupy the niches. These represent the four female martyrs of the early years of the Christian Church, and, since they are not repeated on the inside, they must have served another function in relation to the interior program.

The Present Arrangement of Figural Sculptures

The church has an elaborate, yet coherent program that involves both sculptures and paintings (fig. 2).44 The paintings that are important to the icono-graphic program are labeled in the diagram, but even painted motifs that are unimportant in this respect may contribute to the understanding of the sculptures; for instance, some indicate the relative date of arrival of images in the church.45 The focus in this section being the sculptures, I will mention only the major paintings. The program includes sixteen attached and thirty-four movable sculptures of personages that can be named (the majority of angels and putti are not included as they probably did not have individual names).46 The attached images are in their original locations, of course. They include the disputed Francis and four females on the façade, the eight females in niches above the transept altars, plus God the Father and the decapitated heads of two male saints in niches above the main retable (those called Stephen and Lawrence).47 Among the portable sculptures ten are the holy figures and saints made for placement in large niches above altars, one is the recumbent Francis Xavier figure (reused Christ) placed upon the secondary altar on the Gospel Side, two are the large angels hanging from the piers flanking the chancel, and the remaining twenty-one are apostles and male members of monastic orders, all destined for small niches. These figures are dressed in a variety of clothing types rendered in a variety of techniques, 48 but, as stated above, their wooden parts were imported from an unknown city further south in Mexico.

The portability of these sculptures does not imply major problems in their arrangement. The present positions of those that were focal points above altars generally make sense, and conform to rules behind comparable programs in Mexico. There is no reason to think that any (except one whose misplacement is obvious) are located in positions different from those intended for them in the original program. The large ones could fit only in the large niches, and their imagery was distinctive enough for them not to be confused. The two processional figures from the Jesuit church, in particular, were regularly removed and returned to their niches, so the congregation would have known well where they belonged. In the case of the Virgin of Sorrows, there are clear thematic links between the sculpture and the crucifixion scene above her. The obvious misplacement is that of Saint Ignatius Loyola, a small figure who seems to have been intended for a large niche, and this misplacement will be dealt with below. However, a few anomalies exist among the figures that were intended for small, flanking niches. First, there are anomalies that indicate that the friar-designers' ideas could not be realized as originally envisioned when the sculptures arrived from Mexico. In these cases, accommodations had to be made at the time of installation. Second, there are anomalies resulting from changes in the arrangement after its installation. When the church was no longer under Franciscan control, documents indicate the removal of figures and their storage by native parishioners; this introduces the possibility that some could have been misplaced upon their return to the niches.49 Such accidental changes would have occurred within the series of small apostles and the series of small friars, because the members of these groups would seem to be interchangeable. In addition, there were purposeful rearrangements.

First I will describe the layout of images as it is now, and then explain the anomalies and changes that can be detected, ending with the hypothetical program of 1797. The program starts on the exterior with the four virgin martyrs of the early church. These lack basal inscriptions, but in earlier times had some of the identifying attributes.50 The program continues in the nave with the apostles, who were also members of the early church. Their representations line the nave and continue to the main retable, where four flank the central figures on two stories. The names of the apostles are still on some bases but are missing from others. There are only slight differences in the forms, colors, and decorative motifs ofthe costumes of ten of these. The other two, Peter and Paul, are decorated in markedly dark colors to match the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception between them on the upper story of the main retable. The narrative murals in the nave likewise represent important events in the lives of Christ's followers. To the left of the entrance is the Last Supper, where Christ shared the Passover meal with his disciples and instituted the Eucharist, and to the right is Pentecost, where those disciples that remained after Christ's death and Judas's treachery received the Holy Spirit that made them the first missionaries. Although the names and numbers of apostles vary historically and are a matter of dispute, at Bac the importance of the number twelve seems to have been maintained. The paintings and the sculptures represent Christ's followers at three different times, those at the last Supper, those at Pentecost, and those who became missionaries later. The sculptures are the later missionaries, including Matthias who replaced Judas at Pentecost and Paul who joined later.51

Crossing the nave is the transept with its secondary and tertiary altars. At the end of the Gospel transept arm the two figures in the large niches over the secondary altar are Christ as Man of Sorrows (fig. 5) and above him Francis of Assisi (fig. 6). On the altar is the bier holding the reclining body of Francis Xavier. Flanking Christ and Francis are four male Franciscans. As in the case of the apostles, the names or fragments of names remain on most bases. Those presently in the Gospel arm are: Saints Peter Regalatus and Peter of Alcantara above, and a figure with an illegible inscription and Saint Bonaventure below. Over the tertiary altar next to the chancel are two large niches holding, respectively, Saint Joseph below and Saint Dominic above (fig. 7). Both are relatively small figures of the same approximate size as the small Franciscans and apostles. Joseph is easily recognized from his pairing with the Virgin, his flowering rod (a replacement for an earlier one), and the peg on his arm presumably for the Christ Child. The name on Dominic's base is clear ([St]o Domingo). Both are too small for their niches, so Joseph is on a pedestal and Dominic is on a stack of blocks.52 On the third story above the retable bays are four female nun-saints, who are identifiable from their robes as being from several different religious orders (fig. 8). These do not have inscribed names.53

In addition to decorative motives, there are paintings depicting angels holding a rope and chain, flanking Christ, and angels flanking Joseph holding a grape vine and a fish. Assuming that these four angels form a set, the symbols they hold probably identify them as archangels and/or refer to Christ and Joseph in some way.54

Finally, there are two framed mural paintings, one on top of the other on the south wall of this transept arm. The lower one is a monumental statue painting of the Virgin of the Pillar, who holds the Christ Child. A pilgrim with the shell of Saint James the Great on his shoulder kneels as a supplicant below, and beside him a text reads: "Rezando Vn. AVE Maria Siempre que diere El Relox delante de Qualquier Imagen de n-ra Señora del pilar ganan 100 dias de Indulgencias" ("Saying an Ave Maria whenever the clock dictates before an image of Our Lady of the Pillar earns 100 days of indulgences"). The upper painting is an image of the Christ Child and Mary, perhaps the Presentation in the Temple or the Circumcision. The focus on Christ in this upper painting is appropriate because he is the main subject of the Gospel arm.

On the opposite side of the church, directly over the altar at the end of the Epistle arm is the Virgin of Sorrows sculpture from the Jesuit church, standing below a crucifix set within a cross-shaped depression in the wall. Originally a sculpture of Christ was on the wooden cross still in the depression, but only one arm has survived (it is now in the church museum).55 Flanking the cross are paintings of Saint John and the Virgin of Sorrows with seven daggers focused on her heart area. The side bay niches of the Epistle retable contain four more male Franciscans, flanking the painted Virgin and John above and the sculpted Virgin of Sorrows below. Names on the bases indicate that they are Saints Bernardino of Feltre, Fidelis of Sigmaringen, James of Alcalá, and Anthony of Padua.56

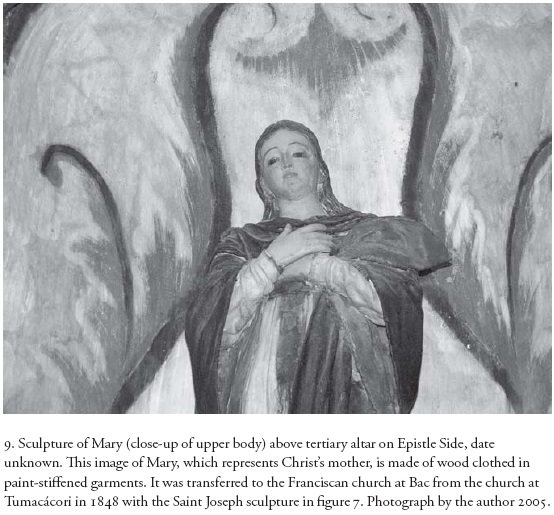

In the large niche over the tertiary altar, the Tumacácori image of Mary (fig. 9) stands on a rough block of wood which tops the remains of the lower part of the pedestal that once stood there. This image forms a pair with Joseph in the Gospel arm. Above her is a fifth male Franciscan, Benedict the Moor of Palermo, who was moved there in recent years,57 and beside her, in a niche on the pier where the transept meets the chancel, is Ignatius Loyola,58 who, like Saint Dominic, is the same size as the small Franciscans and apostles. Interestingly, the large niches above the transept altars containing sculptures of the Virgin lack the flanking paintings of adult angels found on the Gospel Side. Rather, the Tumacácori Mary has abstract interlaces, while the Virgin of Sorrows has groups of putti (vaguely visible are vessel-like objects in the hands of two of these, which are probably thuribles for incense). Above the retable bays the four female saints are all identifiable as Franciscan nuns by their robes.59

On the south wall is a monumental painting representing the Virgin of the Rosary or the Virgin of Aranzazu, a specifically Basque devotion (fig. 10).60 Like the Virgin of the Pillar that balances it in the Gospel arm, it is a statue painting of a Marian icon with the Christ Child. Although it lacks both the praying figure and writing below, the rosary indicates the words that were to be used. Above is a painting of the Child Mary and Her parents, in keeping with the general dedication of this arm to the Virgin. The book being read by the Virgin refers to her learning. Both statue paintings represent the Virgin and Child without emphasizing one personage over the other, despite the dedication of one transept arm to Christ and the other to the Virgin. How they relate more specifically to the other events of the transept is also unknown. One can imagine that they were the objects of petitions from the native congregation, just as the sculptures were.

Between the transept arms are the chancel and its retable, the focus of the whole church. In the center is the figure of the living Saint Francis Xavier, the Jesuit sculpture, placed above the altar and tabernacle. Above him are the sculptures of the Immaculate Conception and the attached figure of God at the top. Flanking the center bay are the four remaining apostles, as stated above, and flanking God are two adolescent angels and the niches with the heads of the two martyrs. On the walls on either side of the retable are narrative paintings, representing the Annunciation and the Adoration of the Shepherds on the Gospel Side and the Visitation and the Adoration of the Kings on the Epistle Side. The nearness of these four scenes to the main altar is logical as they document the events surrounding Christ's birth, His Incarnation in human flesh, which is represented symbolically in the Tabernacle.

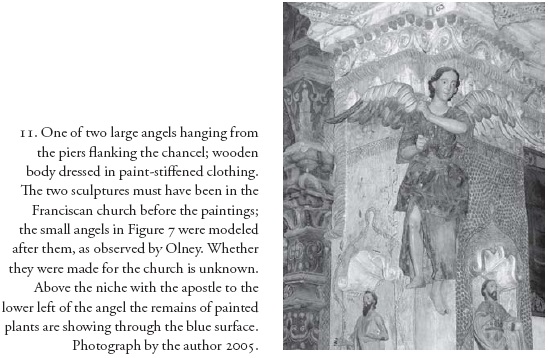

Finally, flanking the chancel area are sculptures of the two large Angels hanging from the piers of the crossing (fig. 11). They cannot be identified specifically by attributes, but given their location they might be the Archangels associated with the Virgin, Gabriel and Michael, since she is the focus of the main retable. Gabriel was the angel who announced Christ's conception (and he is represented thus in the Annunciation painting), and Michael is considered to have been the Virgin's protector. The positions of their legs and feet seem to indicate that they were intended to stand on clouds or perhaps on the devil in the case of Michael, just as the positions of their hands indicate that they probably once held banners.61 They may have served the same function as the smaller two-dimensional angels holding emblems beside the niches with Christ and Joseph in the Gospel arm.

The large figures above the five altars at the north end of the church, just described, dominate the organization of the whole, but there are actually several overlapping organizational structures that work together. Among humans there is a type of chronological ordering from early to late times, going from the early church on the south end — the female martyrs on the façade and the apostles in the nave — to the late church in the transept and chancel—the later friars who are mostly Franciscans. Among the large images in the northern area, the two saints named Francis mix with members of the holy family—Christ, Joseph, and the Virgin. The nave being dedicated to the apostles, the transept arms are dedicated to the suffering of Christ and the Virgin, which the modern saintly descendants of the apostles share. The chancel and its main retable focus on the rewards of suffering: salvation and eternity, through the doctrine of Christ's Incarnation. All altars are activated in the present during different seasons in the church calendar; Mary's altar, for instance, has a small nativity on it at Christmas.62 This was probably true in the past, too.

Within the northern areas of the church the chronological consideration that dominated the ordering of human saints breaks down with the juxtaposition of the early modern humans with the holy figures whose historical lives were contemporary with the figures of the early church. Further, in this northern part, painted scenes are arranged together in areas around sculptures according to theme rather than chronology, and there is even a reverse chronological order from north to south, from the chancel back to the front of the church.63 The events of Christ's birth are around the main altar at the northern end of the church, while events that were historically later are located to the south—Christ's death and the institution of the apostles in the transept arms and nave, respectively. But the chancel conflates Christ's historical birth with the timeless events represented by the tabernacle with the Monstrance on it, the living Francis Xavier, the Immaculate Conception, and Saints Peter and Paul, the founders of the Catholic Church.

As Ahlborn states, the overall theme of the church interior, with its focus on apostles and modern saints, is the missionary project to spread the word of the holy events involving Christ and the Virgin.64 Additionally, I would emphasize the chronological considerations described above, the timeless aspects of the main retable, and the differentiation between Gospel and Epistle Sides, the latter in keeping with Barbara Anderson's analysis of European treatises and ensembles in Mexican churches.65 At Bac the Gospel Side clearly takes precedence over the Epistle Side according to various considerations: especially relative chronology and gender precedence.66 The element of time is expressed in the sequence of earlier Gospel Side events and later Epistle Side events within matched pairs of paintings and major sculptures. In addition, precedence of male over female seems to rule in the dedication of the Gospel transept altars to Christ and Joseph and the Epistle transept altars to two different Marian types.

There seem also to be significant relationships among the major figures on opposite sides of the nave. In addition to the pairing of Joseph and Mary on the tertiary altars—where gender rather than time (and importance) dictates Joseph's location on the Gospel Side67 —there are interesting links of different types among the other figures. The altar at the end of the Gospel arm focuses on Christ as Man of Sorrows and Francis of Assisi who is identified with Christ's suffering.68 In the Epistle arm, the Virgin of Sorrows and the Crucified Christ figure once above her (now missing) were comparable in their positions to the Christ figure and Francis of Assisi in the Gospel arm. There are complex correspondences between these figures across the transept. Christ and the Virgin are comparable as suffering images at earlier and later points during the Passion, and Christ himselfis represented in earlier and later images. At the same time Francis of Assisi bears the wounds of crucifixion and he looks across the space at the Crucified Christ.

These ideas about the pairing of Gospel and Epistle examples seem not to be relevant to the present arrangement of small modern saints and apostles. In fact, even their relationships with the major figures and the paintings near them are unknown. In the small figures, the precedence of male over female does rule, but this is a matter of vertical arrangement rather than transept sides. Males and females are on both Gospel and Epistle retables, but males flank the major images, while the female saints are above the retables. This arrangement is characterized by Lange and Ahlborn as a descending hierarchy, in which the important figures are below and the lesser figures above. At Bac, this is in contrast to the ascending hierarchy of the main retable, where the progress from below to above involves increasing importance from Francis Xavier to the Immaculate Conception to God.69

Anomalies Involving the Apostle Sculptures

It is in the arrangement of the small male figures, both apostles and modern friars, that the greatest number of anomalies are evident. Of the twelve apostles, two, Peter and Paul, are matched in the coloring of their clothing to the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception sculpture that they flank, and the other ten are different from these two in their lighter colored robes (fig. 12).

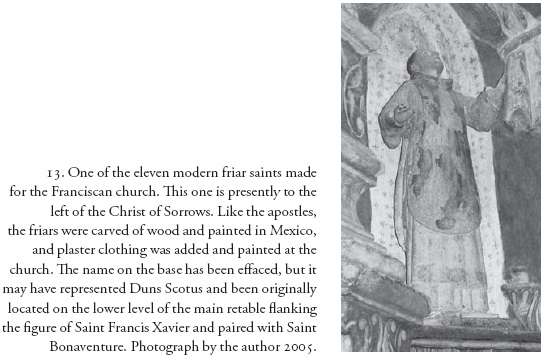

Of the eleven modern friars, nine are Franciscans (figs. 13 and 14) and two, Saints Dominic and Ignatius, were founders of the Dominican and Jesuit orders, respectively. The friars differ from the apostles in several ways. Among them, there is more purposeful variation in faces, expressions, hair styles, age, and clothing. In other words, differences are a matter of individual characterizations, which are lacking among the apostles. Despite their differences, all members of the two groups, both apostles and friars, are of the same construction (wood bodies and plaster clothing) and, except for one apostle to be discussed later, they are of the same approximate height (between 106 and 109 cm). The locations of the two groups form consistent patterns: the apostles are in the nave niches and the early modern friars are in the transept niches. Since there are twelve female saints altogether —those above the retables and those on the façade —as well as twelve apostles, it seems (again) that twelve was the operative number in groups of multiple figures, so the question is why there are only eleven modern friars (I am guessing that one is missing and that its removal dates from after the church's Franciscan period).

The perception that the number twelve was emphasized, along with the patterned locations of types, is behind the identification of anomalies. One anomaly is the presence of only nine occupied niches in the nave, while the tenth is empty. This niche is behind the pulpit and is presently too shallow to hold a figure, but I believe that in the original program it was like the other nave niches —that it held an apostle —and was altered later, as will be explained below. Another anomaly is the placement of one of the friars, Saint Ignatius, in a nave niche. This sculpture not only interrupts the line of apostles along the nave but also does not balance thematically with the corresponding (apostle) figure on the Gospel Side. Given the principle of balance between sides, which obviously dominated the arrangement of images at the church, this niche had to have been occupied by an apostle too. A final anomaly in this area is the location of a Franciscan above Mary, whereas the image in the comparable niche on the Gospel Side is Saint Dominic, who like Ignatius founded a monastic order. Logic would place Ignatius in the Epistle niche to balance Dominic in the Gospel niche.70

The obvious correction, the removal of the Franciscan saint above Mary and placement of Saint Ignatius in that niche, result in an empty nave niche. If one were to remove one apostle from among the four in the main retable, the only place with extra apostles, to fill it, there would be three apostles left there. I suggest, then, that the third one be removed also to a nave niche, the one behind the pulpit. In other words, since there are twelve apostle figures and ten niches altogether along the nave, one would be tempted to put apostles in all the nave niches, the one now occupied by Ignatius and the altered, empty one, and leave only two apostles in the main altarpiece niches — Peter and Paul, who obviously belong there.71 I believe this is the solution and will suggest other occupants for the empty niches below them.

Otherwise the arrangement of the apostles is unknown. Perhaps paintings in particular areas will give clues — e.g., the painted images of the pilgrim (identified with Santiago) and Saint John in the Gospel and Epistle arms, respectively—or perhaps there was some sort of internal hierarchy among them, as in the named villages on the Río de los Apóstoles. Or perhaps there was no significant original arrangement of these figures.

The Placement of Two Franciscans in the Main Retable

The removal of the two apostles from the lower story of the main retable would leave two empty niches, which I suggest were occupied by Franciscans in the original plan of 1797. Lange and Ahlborn suggest Jesuit saints in these positions, arguing that the entire retable followed a Jesuit model, but I disagree.72 Although the Bac friars were forced to retain Francis Xavier as the dedicatory saint, they would have wanted some of their own brothers in prominent positions on the retable. The most likely candidates for this position are the two figures flanking Christ in the Gospel arm. One is unidentified (fig. 13), his basal inscription being illegible, and the other is labeled as Saint Bonaventure (fig. 14). There are several reasons for arguing for the placement of these two on either side of Francis Xavier. First, they are different from the other small Franciscans in wearing red and white church vestments rather than the brown, rough cloth robes and rope belts of mendicant friars. The vestments —on one a cassock, surplice, and chasuble, and on the other a cassock, surplice, short cape, and biretta—are those that clerics would wear while officiating at the mass in the chancel of a church. Placed in the main retable, these sculptures then would be in the location dictated by their garments and would be comparable in this respect to the image there of Francis Xavier, who wears a real cloth cassock. The depiction of birettas on top of two of the columns of the retable indicates the same.73

Second, there would be significant formal interrelationships among these two and the other figures in the main retable, as well as iconographic relationships with the paintings that flank the retable. The figure without a basal name is the only small figure in the church with head and eyes raised, a position that would make more sense if he were looking up at something, specifically the Immaculate Conception on the second story of the main retable, than it does now in the Gospel retable, where he looks up at nothing. Bonaventure does not look up, but the biretta on his head would echo that of Francis Xavier, and the red and white coloring and painted lace on the clothing of both small Franciscans would complement the larger figure's costume (which is changed from black to red according to season).74

My final suggestion is that the unnamed figure might have represented Duns Scotus, the first and best-known theologian to argue for the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception and the one connected with it by the Franciscans.75 In this capacity he was represented previously in a mural at the great sixteenth-century friary at Huejotzingo in Puebla, Mexico, and in a sculpture on the eighteenth-century façade of one of the Franciscan churches in the Sierra Gorda, Querétaro, Mexico.76 In both he is one of two figures flanking the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception; in the mural he is with an opponent to the doctrine, the Dominican Thomas Aquinas, and on the façade, he is with another supporter, Sor María de Agreda. His dress, posture, and facial hair vary in different representations, but at Huejotzingo, he wears a biretta, the sign of an officiating cleric.77 Although Saint Bonaventure denied the Immaculate Conception, a doctrine that the Franciscans supported as a group by the time Bac was built, he was an important church official, and this fact may be more relevant to his placement in the main retable. Perhaps his specific connection in the program was to the Annunciation, as he is credited with having instituted the ringing of the Angelus bell in honor of that event, and this may indicate that he was on the Gospel Side of the chancel, where that subject is featured in a painting.78 Otherwise, since the poses of these two Franciscans are similar although reversed, it is difficult to say which was on the left and which on the right.

If these two Franciscans were moved to the main retable, and if the incorrectly placed Saint Benedict of Palermo (now in the niche that should hold Ignatius) were put in one of the spaces left by these two, or another niche proper to the Franciscan friars, one transept niche would still lack a figure. It is for this reason that I believe one Franciscan is missing.79 I would guess that, as in the suggested ordering of the main retable, the organization of the Franciscans had significance for the friar-planners; they were meant to relate to each other, the painted decorations, the figures they flank, and the females in niches above them. However, the arrangement probably lacked the same type of interaction across the church that was suggested in the case of the major sculptures. Local relationships might be hypothesized after further study of poses, gestures, and events of the lives of the personages represented.

In summary, the original program of 1797 probably featured the twelve missionary apostles in a line of ten niches along the nave and in two niches flanking the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception. Images of Joseph and Mary, as parents of Christ, were above the tertiary transept altars and above them were the images of Saints Dominic and Ignatius, the founders of the two other important monastic orders in northern New Spain. The smaller niches around the major figures in the transepts were occupied by Franciscans (one image now missing), and the two Franciscans dressed in priestly robes were located in the lower-story niches in the main retable, where they flanked the dedicatory saint, also dressed as a priest.

The Enlargement of the Pulpit and Rearrangement of Figures

If the small monastic and apostle sculptures were moved from their original positions in the program, when did this happen, and who did it? It is logical to think that the changes occurred in tandem with the installation of the present pulpit, and the alteration of the niche behind it. There may have been some sort of pulpit in the area from the beginning; a difference in the carving of the lower and upper parts indicates that they were not made at the same time. If the change was an enlargement, it involved an upward expansion so that the pulpit covered the niche. Visual observation reveals that plastering in the area covered a painted red-and-white hatched frame like those around the other nave niches. This seems to indicate that the niche itself was originally like the others and that it was reshaped (the base and crowning volutes being removed) when the area was replastered. Why a shallow, empty niche was preserved is a mystery. It is now popularly believed to stand for the traitor Judas, an unlikely association in the original conception of the program.

It was probably the need to place the apostle from this niche elsewhere that led to the rearrangement of the other small figures. This occurred sometime before the 1870s, when the first photographs of the interior reveal the present pulpit and arrangement of Franciscans and apostles80 (I am not aware of previous mentions of the pulpit). To determine when these changes were made needs more thorough investigation. However, I would guess that it happened after the church's Hispanic period, when the early representatives of Us Catholicism retook the church and restored it. This possibility is supported by documentary mentions of building activities. The first concerns Bishop Lamy's friend Joseph Projectus Machebeuf. Having arrived at the church in 1859, he reportedly "took steps for the repair and preservation of [...] San Xavier del Bac [...] and succeeded in putting it in such condition that it could be used for services."81 In 1863 the Jesuit Carolus Evasius Messea talked of plans "for the restoration of the mission [...]" on his way to take up residence there.82 And finally, Jean Baptiste Salpointe, who arrived at the church in 1866 and became Bishop of the area later, made further repairs.83 Such non-Franciscans would not have been bothered by the removal of Franciscan figures from the main retable and their replacement by apostles, a group whose original number of twelve probably needed to be maintained. The locating of Ignatius in the empty pier niche may or may not have been connected with the pulpit project. The Jesuits, who returned to the site in 1863 would have been pleased to see their founder in the more visible position where he now resides, and may even have put him there, even though he does not match the other apostles in style. Unfortunately, the niche now holding Ignatius is not visible in the 1870s photographs, so whether he was moved before that period is not known.

The "Communication Gap"

Some anomalies being understandable as the result of later rearrangements, the remaining inconsistencies/problems in the program seem to be the result of imperfect communication between one or both of the friars involved and the distant sculptors who made the figures, or even between the two friars, as Llorens arrived at Bac after Velderrain's death. Interestingly, most of the sculptures that suggest this imperfect communication are in their proper iconographic locations (with the obvious exception of the Ignatius figure) —evidence that Llorens knew the general outline of the program. The "communication gap" is indicated first of all by the different size and style of one of the nave apostle figures. This figure has the name of an apostle on the base (S. Math., presumably San Matheo [Saint Matthew]) and he wears the same type of classical robes as the other apostles, but he is anomalous in that he is larger in size and has markedly different facial features and hair style. His hair and beard are short, whereas the other apostles have long, curling hair and beards, and he is probably about 10 cm taller (as judged by his fit in the niche, not his stated height in Ahlborn's study).84 It would appear from this that only eleven matched apostle sculptures arrived at the church, meaning that the intentions of whoever commissioned the sculptures were not understood at the place of production, and that this larger figure had to be dressed as an apostle to make their number twelve.

The second sign of possible miscommunication is the fact that a number of sculptures, likewise in the correct positions iconographically, are of inappropriately small sizes for the large niches that they occupy. Most noticeable in this second category are the figures above the tertiary altars—Joseph and Mary below and Saints Dominic and Ignatius above. While the present Joseph and Mary figures seem to have been added to the program sometime after 1848, they were probably preceded by equally small sculptures in the same places, as argued above. The style and technology that Dominic and Ignatius have in common with other sculptures at Bac indicate that they were part of the ensemble installed in the 1790s, but they also are too small for their niches. What is to be made of this? In fact, no figures in the church, besides those that were located (correctly) above the other altars, are large enough. Since the small and large niches probably indicate the numbers of small and large sculptures anticipated, one logical conclusion is that whoever placed the order for figures and had the niches made wanted some of the figures to be larger in size. It is also possible that the size difference was not considered to have visual significance, or else one or the other of the two friars changed his mind about niche size after the order was placed. Or this discrepancy resulted from the fact that Velder-rain died before the project was completed and Llorens inherited incomplete information about it. At any rate, all four figures above the tertiary altars were made too small for the niches.

Whichever friar received the new images at the church had to solve the problems. The small figures, all being sent without robes and names, had to be dressed, decorated, and labeled at the church, and it was here that he and his installers made the changes dictated by the predetermined program. Whoever dressed them had to choose the appropriate clothing, while considering the hair, age, and expression of each figure sent. They were aware that the men with longer hair and beards were apostles, and that those with individualized expressions were modern friars, and they must have been able to distinguish Joseph from these as well as the Virgin. Given that there were only eleven matched apostles, they had to make the "mysterious" larger figure into an apostle and they had to put bases under the four figures that were too small for their niches. Another indication of a mismatch is the depiction of the Franciscan Benedict of Palermo (a Moor with dark skin) as a man of light complexion.

The final problem that could be due either to this communication gap or to changes later in the church's history is represented by the figure of Christ. It is the correct size for its niche, but it is posed to carry a cross and there is no room in the niche for a cross.85 In addition, it was made as a procession figure, which would typically be removed from its niche, but easy removal is blocked by the location of the bier in front of it. And although there is evidence of the moving of the bier around in the church, I am not aware that this was ever the case as regards the Christ figure.

These problems of figure sizes, poses, and arrangements are definite facts, while the suggested solutions are tentative. Further investigation may produce alternate scenarios.

Questions of Workshops and Training: The Imported Works86

The main decoration of the church at Bac occurred in the final years of the Spanish Baroque, when the arts of painting and sculpture were linked in many ways. In the Hispanic world it was typical for the production and decoration of sculptures to involve separate steps using multiple artists, who were trained in different skills or the handling of different materials. The sculptures sent to Bac were most likely the results of the collaboration of a sculptor or sculptors and a painter or painters. In the case of the sculptures that were dressed at the church, in addition to the original carver/s and painter/s in Mexico, there may have been as many as two additional artists, the plasterer who clothed them and the painter of the clothing.87

In addition to the working of multiple artists on single works, a single artist might practice in what we would consider very different artistic forms. A painter, for instance, might paint on flat as well as sculpted surfaces and with the different types of paints required by different surfaces. All painting at Bac is on plaster, and the same style of flower depiction is apparent in wall painting as on clothing. However, in the case of artists who worked in more than one medium, talent and training might lie in one artistic form but not the other. For instance, an artist might be a great painter of sculptures, but not of human bodies and narrative scenes. This too seems to have been the case of the artist/s who worked at Bac.

Two separate types of problems are posed by the imported objects and by the works produced locally. Nine major sculptures —the two Jesuit sculptures, the two Tumacácori sculptures, the reclining Francis Xavier (reused Christ), the remains of the Crucified Christ (just an arm), the Immaculate Conception, and the two large Angels — cannot be linked to other sculptures in the church. In contrast, commonalities in style indicate that twenty-five others, two major sculptures (the Christ as Man of Sorrows and Francis of Assisi) and the twenty-three small ones that still remain in the church seem to have been made by one workshop of carvers or a group of related workshops. Although the places of origin of none of the figures have been determined, this group provides interesting data about its creators, who were definitely multiple. Given the variety and circumstances of their clothing, evidences of the carvers in this workshop are seen only in the faces, hands, and feet. The large Christ as Man of Sorrows and Francis of Assisi figures are close enough in style to be from the same workshop, but not close enough to be the creations of one carver. The Christ figure, in turn, displays similarities with the eleven apostle figures that form a stylistically coherent group, but the apostles are not the creations of the same artist, and there is evidence of a variety of hands among them. The other small figures, Saints Dominic and Ignatius and the Franciscans form another group, also apparently by more than one artist. Among these, the small Saint Dominic so closely resembles the large Saint Francis that they must be the creations of the same carver, but not the same artists who created the others. There are also possible connections between the small Benedict of Palermo and the large Immaculate Conception, but this is more tentative —given the distance of both figures from a viewer on the floor—and it needs confirmation from further examination.

So style characteristics in faces seem to indicate a single workshop, but the fact that the majority of figures lacked clothing when sent out may indicate a workshop focused on carving and perhaps the painting of encarnación (flesh) but not estofado (clothing) painting. All the painting or creation of clothing would have been done elsewhere. The Christ, apostles, and small friars were made to be dressed else where, while Saint Francis and the Immaculate Conception (if she was part of the commission) were conceived as dressed but were decorated elsewhere in different styles of estofado. Interestingly, among the apostles Peter and Paul seem to have been painted at the church in the same colors as the Immaculate Conception, and only closer investigation will reveal how close in style their locally-made decorations are to the imported estofado of the larger figure.

It is obvious in the differences in carving that there were a variety of hands involved and varying levels of skill, corresponding to a hierarchy based on both talent and training. The large sculptures of Christ and Saint Francis seem to have been the creations of two artists working in very close styles. Their faces are not in the academic styles of sculptures published in Mexican studies; presumably they were from workshops in less peripheral areas of New Spain.88 Yet, they are strongly conceived characterizations, with the face of Christ being a more impressive image. They may be productions of masters (maestros)in the hypothetical workshop. In contrast, the treatment of the eleven matched apostles suggests lesser talents — oficiales and aprendices (craftsmen and apprentices). Some of the faces are clearlyderivative in style from the large Christ sculpture, and they are all frozen in expression and lacking individualized characterization. The style of the anomalous twelfth apostle, the one that is larger than the others, indicates a different artist in the same workshop, as he resembles the two large sculptures in other ways (for instance, in the ears).

In contrast to the apostles the set consisting of the nine Franciscans and Ignatius and Dominic is difficult to define, more because of the inaccessibility of the figures, even using a telescopic lens, than of the differences in their characterizations. Close-up photos reveal their creators as being as skilled as the artists of the major figures. The faces are more enlivened and varied than the apostles', and individuals of different ages and temperaments are depicted. Only closer examination of details of ears, hands, hair, painting, and other traits will indicate how many artists were probably involved, and whether the suggested workshop ties are plausible.

Other notable creations are the two large Angels attached to the piers flanking the chancel. Although nothing ties them to the other sculptures, Robert Olney argues for their presence in the church before the decorative wall painting, presumably in the 1790s, since they provided models for the position of the legs in many figures, most notably in the two-dimensional painted angels (seen in fig. 7).89 But these sculptures seem to have been imported from a source different from the rest of the ensemble.

Artists Working at the Church

Wherever the wooden sculptures were carved, those that arrived without robes were plastered and painted at Bac. So in both two- and three-dimensional works done at the church the focus was on the arts of shaping and painting plaster. There are a great number of examples of both arts (fig. 15), and there are evidences of different levels of skill as well as evidences of later repainting. The question is: how many artists worked at the church, and when? As in the case of the sculptures, the names of the artists probably cannot be found, but future studies of the visual and material evidence might suggest their numbers, training, and sequence of work, as well as distinguishing between work done at the time of initial decoration of the interior and later changes and repairs.

In the Hispanic world an elaborately decorated interior like Bac's would have required many specialists. 90 As explained above, multiple artists might work on a single production and single artists might work on different objects. The number of artists employed and the quality of their work depended on the wealth of the patron, as did the value of the materials. Even at Bac, where faux paintings allude to unattainable materials, a variety of specialized skills were required for its initial decoration. These included: the design of the building and the program of the whole, the translation of the design of the building into a real structure of bricks, the shaping and assembling of brick armatures for the plasterer, the modeling of plaster over the brick forms and wooden sculptures, the decorative painting on plaster walls and clothing, the figurative painting on plaster, and the application and painting of gold and silver leafon the main retable.

Because of the volume of work at Bac, there had to be multiple artisans involved. However, because of the poverty of the area and the distance from metropolitan Mexico, the myriad tasks had to be accomplished by a small number of trained artisans directing apprentices and amateurs. We know that Indian workers did the manual labor, and it is now fairly certain that the master mason who directed the work was a Spaniard or New Spaniard named Ignacio Gaona; his name is found in both oral accounts and documents.91The number of trained artisans he brought with him is undocumented, but, as in the case of the sculptures created in Mexico, the training, numbers, and relative talents of the creator/s should be visible in the artworks themselves.