Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

versão impressa ISSN 0185-1276

An. Inst. Investig. Estét vol.28 no.89 Ciudad de México Set. 2006

https://doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.2006.89.2225

Artículos

Maya Painting, in a Major and Minor Key

Mary Ellen Miller

Yale University.

Abstract

In this essay, Maya painting traditions of both small scale and monumental are considered in light of two other world traditions of painting, Greek and Moche. Attention is given to the possible relationship between slip-based vase painting and wall painting, as well as the nature and implications of such a relationship, with some consideration of both style and iconography. For Maya painting, particular attention is directed to the wall paintings of San Bartolo and Uaxactun, Guatemala, and Calakmul and Bonampak, Mexico.

Resumen

En este ensayo, las tradiciones pictóricas mayas tanto a pequeña escala como a escala monumental son consideradas tomando en cuenta dos tradiciones pictóricas, la griega y la moche. Se presta especial atención a la posible relación entre la pintura de vasijas engobadas y la pintura mural, así como a la naturaleza e implicaciones de dicha relación, señalando algunas consideraciones tanto de estilo como de iconografía. En cuanto a la pintura maya, se analiza particularmente la pintura mural de San Bartolo y Uaxactún, Guatemala, y Calakmul y Bonampak, México.

Of the many exciting discoveries revealed both by intention and accident in Mesoamerican archaeology in the past decade, Maya painting has held many surprises. Perhaps nothing has been so confounding to received wisdom as the discovery of the San Bartolo paintings in Guatemala,1 but equally stimulating is the recently uncovered painting of the North Acropolis at Calakmul.2 What will make the study of ancient Mexico painting possible in the future is the remarkable testament to ancient artists in the Proyecto de Pintura Mural, the comprehensive document directed for so many years by Beatriz de la Fuente.

For a long time, the paintings of Bonampak stood as both example and anomaly. Now new discoveries make it possible to amplify the larger picture of what we know about Maya painting during the first millennium. Is there really a Maya painting tradition? Can we see schools and patterns emerging? What relationship does Maya painting have to other media? Does wall painting intersect effectively with vase painting, or with sculpture? Perhaps one of our problems in understanding the relationships is that modern scholars, whether they know it or not, see the larger question of the arts through the lens of Aristotle, who divided the arts into the major and minor arts from one another, and who attributed value to scale. Typically, art historical studies separate one medium from another, and painting and sculpture rarely are treated in the same study as smaller scale works, especially those in precious materials — in the case of Maya art, especially jade, but also ceramics. Aristotle himself probably could not have imagined a painted work that was also sculptural, as opposed to painted sculpture, which of course was the usual procedure for Classical and Hellenistic Greek sculpture. But just consider, for one moment, the typical Early Classic Maya basal flange bowl with lid, if such a thing as a typical Maya object can be said to exist: three-dimensional forms dissolve into two dimensions on the lid, for example, and the three-dimensional form of the cormorant head seems to pull a fish out of two dimensions into three, as if to transform the fish at the moment that it is consumed (fig. 1). In this case the supporting legs return to three-dimensions, but the painter relishes transforming each leg into a snout-down peccary, painting a long-lashed eye and letting the firing hole read as if it were the mouth, and making the functional take on what may have been an amusing form. Maya potters executed similar forms dozens of times, making of them familiar tropes. But key here is that the sculptural form and painting are equally important, and one cannot be divorced from the other. Maya art has no interest in conforming to Aristotelian models, neither in the separation of media, nor in scale: major and minor are not useful distinctions for Maya art, and especially Maya painting.

For purposes of comparison, we might look briefly at what we know of two other traditions where slip-painted ceramics flourished: 5th century BC Greece and Early Intermediate Period Moche. In both cases, very few wall paintings survive, fewer than in the Maya case. Yet scholars have drawn comparisons between wall painting and vase painting. For the Greeks, the evidence is largely textual, and those descriptions are based in Roman writings; for the Moche, who had no texts, the evidence is purely archaeological and visual. Based on both texts and the surviving fragments, scholars of Greek painting have argued that vase painting depended heavily on monumental examples, deriving subject matter and evolving styles from the larger works. Although names of Greek vase painters (e.g. Euphronios) have been recovered in some cases and constructed in others from the pots themselves in modern times (e.g. Berlin painter), they are not the names of wall painters known historically. Recently, the latter approach — of constructing names for identifiable painters — has become feasible for Moche painters of ceramics as well.3

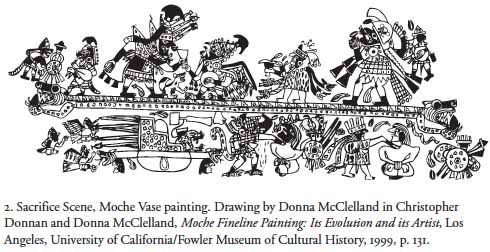

Nevertheless, at least for Classical Greek art, the traditional notion that the monumental is more important than the small-scale and hand-held has depended on the survival of named painters and perhaps on the wealthy contexts of their work, as well as the complex social relations created by the scale of works that allow public viewing. Generations of viewers and pilgrims observed the paintings by Polygnotos at Delphi; both Pliny and Pausanias commented on subject, style, and significance. Modern scholars generally believe that the vase painter Polygnotos took not only his name but also his monumental style from the wall painter.4 For the Moche, the revelation of recent years has been the very notion that the imagery painted (and sculpted, for many Moche pots depend keenly on the integration of the two media) on vessels conforms to a larger mythic sequence (fig. 2), known in its most monumental form in wall paintings at Huaca de la Luna and Pañamarca5 and in its greatest complexity in vase painting.6 However, as further revealed at Sipán, the subject of painting was a lived, believed, and re-enacted supernatural narrative.7 In short, both wall paintings and ceramic vessels underrepresent the complexity of the narrative as seen in the re-enacted — both lived and terminated — sequence performed at the death and burial of a Sipán lord. Moche lords died, if not lived, according to a supernatural narrative that dominates vase painting and wall painting.

What about the Maya? Does painting evolve as an independent tradition or as part of sculpture? What can be said about the relationship with Maya painted ceramics? The "codex-style" ceramics have long been thought to bear relationship with Maya books: do they play a role in the development of other arts? Let's look briefly at a few examples of monumental painting, and let's also look at some of the assumptions that usually dominate inquiry on the subject. To begin with, we need to dispense with sculpture, and especially the stela, as exemplary for all other media. Because the sculptural record is so vast and thrives at so many cities simultaneously, it holds a place of privilege in Maya studies. Additionally, because Tatiana Proskouriakoff's volume, Classic Maya Sculpture (1950), provides a structure for examining essentially every lowland sculpture of the first millennium, her modern-day framework has come to be the measure of all Maya works; when the Bonampak paintings came to light, Proskouriakoff analyzed their date by judging them against sculpture. But sculpture may not be the most useful measure of Maya art, and especially not for painting.

Despite their isolation as a uniquely complete early example, the paintings of San Bartolo (fig. 3) are the exception that changes all previous conceptions. Painted c. 100 BC, the paintings bear little, if any relationship to ceramics of the day, whose shapes rarely offered any surfaces for the sort of narrative seen on the interior walls of the building now called Pinturas Sub-1.8 Unlike any other substantive corpus, the paintings reveal sophisticated manipulation of Olmec precursors in both style and iconography, and on the west wall, the dominant figure, the Maize God, has been painted with features known from Olmec objects, valorizing and distinguishing this figure from others with archaisms. Figures fall into coherent groupings, as if sequential or simultaneous but distinct narrative elements. Heather Hurst has noted that these groupings fall with regularity and predictability across the walls, as if mapped and sketched onto the prepared white stucco walls from yet some earlier prototype, especially on the north wall, where a series of similar but distinct figures appears (Heather Hurst n.d.). The painters who produced the San Bartolo murals worked with confident, sure strokes, deciding to depict legs that overlap in some instances, especially for attendant, rather than principal, figures, offering an early clue to the foreshortening that would develop later. The painters knew exactly how to approach the question of placing the human form in relation to the ground line or to suspend it in air; when yellow feathers are called for, the recipe of pigment, binder, and brushwork are known quantities to the artist, who dispatches such details with calligraphic flair.

Freestanding stone sculpture of the period, in contrast, faced both technical and artistic obstacles, at least in the Peten, and insofar as archaeology has revealed. The earliest monuments discovered in situ underscore the difficulty of working with limestone. Nakbe Monument 1, of the Middle or Late Formative, depicts two figures facing one another, perhaps the Hero Twins; the stone retains the forms of the boulder from which it has been shaped, limiting sculptural possibility. Other examples in the Peten and adjacent Mexico are rare and difficult to date to the period of San Bartolo. In the Late Formative, the most sophisticated developments in terms of deploying two-dimensional human forms take place at Izapa, Mexico, and in Guatemala, both in the highlands and along the Pacific slope, at Abaj Takalik and elsewhere. All across the Maya lowlands, sculptors also worked with architects to adorn buildings with massive stucco heads, usually of deities. These heads were also painted, but the painting principally serves strategic, social, and decorative purposes, using brilliant colors that make the works legible at great distance.

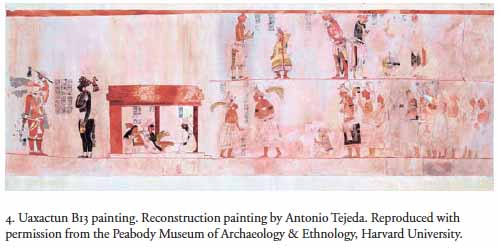

Despite the visual power of these massive stucco heads, they were to fall out of favor by the Early Classic period, just as the two-dimensional stela practice flourished. Ultimately, the stela became the dominant form of monument on the Maya plaza,9 articulating Maya buildings, emphasizing historical figures in roles of both supernatural impersonation and dynastic ritual, set within a chronological framework. What we don't know is whether there was continuous, parallel development in monumental painting, but the examples at Río Azul, in particular, would suggest that painting also flourished, although most surviving Early Classic examples are known only from tombs. Few Early Classic walls that could have supported wall painting survive in any sort of acceptable condition for painting. When a rare painted palace wall was uncovered in Uaxactun Structure B-13 in 1937,10 little was made of it, but much can be said now: like the San Bartolo paintings of 600 years earlier, the Uaxactun paintings (which cannot be later than AD 500) reveal a fully developed and flourishing tradition that far exceeds the sculpture of the period. If painting is advanced in the period, then sculpture lags behind. Where painting takes risks, sculpture repeats known patterns, engaging in dialogue with itself. Of course, one might say that these are gross generalizations, and they are: one could counter that sculpture responds to the patron, and to the context, that royal representation requires a conservative approach, in order to emphasize and underscore ancestors and continuity. If sculptural representations do more than represent — if indeed they embody the king's power — then they bear the additional burden of acting in his stead, which may further complicate the question of conservatism in sculptural form.

Nevertheless, regardless of where one situates oneself, the Uaxactun B13 paintings reveal sophisticated complexity in 5 th century art (fig. 4). Figures operate in space, within architecture; the artist represents musicians in a dense pack, overlapping one another, perhaps suggesting circular movement. Inside a house, women gather in a familial grouping, their bodies seen in profile and with casual mastery of the informal gesture. A single musician turns to the person behind him, a gesture that becomes commonplace within a century or two. Running below the scene is a 260-day count, the only one known from Classic Maya times, with punctuated days, as if to relate the scenes above to particular days. Here one sees that the calendar could be used not only to record the deeds and events of Maya royalty but also of a noble household, and in case there was any doubt about which calendar would be used for the simple shorthand of the days of one's life, the answer is here: the 260-day tzolk'in, beyond the day itself the most fundamental unit of the Mesoamerican calendar. Overall, Uaxactun reveals that narrative forms and groupings usually associated with the Late Classic period and generally known from ceramic vessels rather than in monumental form can be seen to have taken form generations earlier.

And what about ceramics? The late fourth-century move to the ceramic tripod began to liberate the painter of ceramics. Up until that date, his most successful works combined sculpture and painting, precisely as seen in figure 1. Clearly a vessel form and design imported from Teotihuacan, the tripod provided flattened, extended surfaces that opened up a new space for painting, in sharp distinction to the forms of the basal flange and its lid. Originally linked to anthropomorphic or zoomorphic lids and supported by tripod feet, the cylinder embodied the royal or supernatural being, allowing his essence or substance to be understood as the vessel's contents. This cylinder form freed itself from these elements over the course of a century, resulting in a simple form ideal for painting in clay slip and for the revelation of narrative. In so doing, the cost of making a cylinder vessel also dropped off sharply, when the fussy feet and lids were no longer required. The text of the 7 th and 8 th century cylinder spells out that its contents would usually have been a chocolate drink. Potters made cylinders in a range of shapes and proportions, from more globular cups to tall, straight-sided containers that would have held nearly two liters. With this drop-off in price, pots proliferated. From the date of the initial move to the cylinder tripod, the ceramic painter gained a surface, something akin to a canvas, although time-consuming post-fire stucco paint was often used; by AD 650, the simpler form had made it possible for distinct and powerful schools of both potting and clay slip painting to emerge that would thrive until about 800.

Now into the mix comes a most astonishing discovery: the wall paintings of the North Acropolis, Calakmul.11 The imagery bears clear relationship to Maya painted ceramics from the 7th and 8th centuries, with the red frame and narrative imagery (fig. 5). The representation of the human form, including the energetic and powerful standing female figure, cannot easily be distinguished from painted ceramics of the period; the animated and flat hands of this same woman grasp the large pot in what is also common convention in Maya ceramic painting. Almost impossible to imagine within the framework of Maya sculpture of the period, such a work can be recognized as possible when seen in light of the Uaxactun painting and what we know about ceramic traditions.

Here we see the Maya artist in easy mastery of the human form, the weight of the heavy pot shifting to the woman at left, who may well be a host of great parties celebrated in adjacent palace chambers; her presence here would seemingly signify noble responsibilities for feasting. She has also absorbed the weight of color in the scene: her blue dress and adornments dazzle in the scene, juxtaposing her wealth with the mousy grey dress of the servant or slave in front of her, yet both conform to the convention in which only women wear body paint on the face. Not only color but the absence of transparency may indicate the lower status of the servant woman, indicating the very coarseness of the cloth she wears. The larger woman speaks, her mouth slightly parted to reveal teeth, rarely shown except by captives in Maya art; a distinctive red line outlines her lips. The seated male at right, while clearly subservient, nevertheless wears a textile patterning characteristic of a sajal in the Bonampak paintings, and fancy double-weave borders edge his textiles. Additionally, he wears a headdress typical of scribes, suggesting a valued status. Although he seemingly lifts it to his lips, the spiky ceramic vessel in his hands would not be appropriate for drinking; he may, in fact, be raising this vessel in order to present it to the protagonist, and he may speak as he does so. His counterpart, at far left, also in a scribal headdress, opens his mouth but directs his gaze downward, as if to avoid looking at the protagonist's body. The artist has adorned every figure with a blue-green element, so that at least a tiny daub of the brilliant color is carried from figure to figure.

In the Calakmul painting, the artist follows traditions known to both the painter of ceramics and the muralist; the flat, grasping hands so typical of ceramic painters can be juxtaposed with the fleshy hands of the male attendant at right, which are drawn in ways that relate to late Yaxchilan sculptures. His visible foot, in particular, can be likened to those of the seated captives in Bonampak Room 2; the gauzy blue cloth with its intentional transparency that reveals the voluptuous female body at left shares commonalities with the group of enthroned women in Bonampak Room 3, but here, the artist has paid particular attention to the breast, right down to the nipple, along with the soft curves of her torso. In short, our painter reveals himself to be a master of both convention, revealed in the familiar representations of hands and feet, and perhaps a comfortable innovator, especially in the rendering of the woman in blue.

Finally, a few words about the Bonampak paintings, where a to-and-fro relationship with ceramic painting has long seemed to me to be in evidence. The exterior of Structure 1 is painted with a text that runs under the soffit, rimming the front façade of the structure as if it were a cylinder vessel. Late in the sequence of what we think of as Classic art, Bonampak inevitably draws on monumental sculpture as well as ceramic painting, but in its complexity, it may also, in turn, have inspired works in other media in its day. Although the Bonampak paintings remain unique in their scale and complexity, they, too, reveal the push and pull of the avant-garde and the retardataire. Tikal Burial 116 contained a vessel that archaeologists quickly nicknamed the "Bonampak vessel," based on imagery that clearly related more closely to Bonampak Room 1 paintings than to any other work. Securely dated no later than 726,12 the vessel's figures in white robes make gestures and feature detail in rendering that align very closely to those in the monumental painting. (The original was destroyed and cannot be examined.) Yet the Bonampak paintings cannot be earlier than the dates inscribed within them, 790-791, or at least 65 years after the Tikal vase was made. As much as we like to think of the Bonampak paintings as unique, they, too, belong to a tradition, but by their day the tradition is well-established in many media. It may be that the monumentality was fresh and unusual, or even the manner in which architectural forms, especially the "wrap-around" pyramid of Room 3, found new inspiration in the painted ceramic vessel, turning the sort of imagery typically found on the exterior of a pot inside out.

The painters of the Bonampak murals, in distinction to the painter of the Calakmul mural, did engage more directly with the sculptural tradition. This relationship can particularly be noted in the rendering of hands and fingers in Room 1 and in the captives of Room 2. On painted ceramics and in the Calakmul painting, artists use a particular shorthand to render hands, making them flat and spidery, a type of rendering known otherwise from pots, and possibly from a few depictions of captives. Of the many things one might say about both sets of murals, one would not be that the artists are struggling to develop artistic voice: rather, one might say that in the consistency of pigments, resultant colors, characteristics of line (and thus of paintbrushes), the tradition is in full flower. Both are also defined by the red line, which opens up space and then compresses it at Bonampak. The red line that defines the space of representation for ceramics, books, and monumental painting unites these Maya traditions. We cannot say with certainty that the practice originated in books, but the convention asserted order not only in books but also on painted ceramics, where the very violation of the red frame became an act of the artist.

Monumental painting or ceramic painting? Is one of these media racing ahead of the other? For the 5 th century Greeks, the answer would seem to be that monumental painting always has the lead.13 Perhaps for the Maya the problem is not a simple one of donor and recipient, but rather the larger cultural processes. Perhaps the problem is also one of lost materials. Maya art of the 7 th and 8 th centuries, at its two-dimensional best, is an art of calligraphy, an art keenly tied to the developments of writing. In comparison to writing, the representation of the human figure in time and space lagged behind the inscriptions earlier in the millennium. Then, during the seventh and eighth centuries, the Maya artist sought to position human and divine actors in just that time and space. Because a Maya artist was also a scribe, he would have understood the full range of capability of Maya writing and arithmetic and their ability to represent something. Of course, all representations always underrepresent the complexity of human actions, but the Maya scribe may well have sought greater visual representation, one with greater specificity of place and one with narration and time embedded, driven by the achievements already in place in writing and calculation. He could master that something. It may well be that painting, both wall and ceramic, responds to developments in painting and drawing on the small scale, on cloth, on fig paper, and as the latter is formed into screenfold books, or codices. Although no Classic-era book survives, the occasional extended composition of the later Dresden Codex should make us aware that it may have been a commonplace, framed with red, to draw and paint across one page to the next. Books commonly appear in painted Maya scenes, and these books may be the places of memory and narrative. Private and easily hidden, they may also have been sites of innovation, as well as means of transmission across both geography and time. Although we think of books as the domain of men, we should keep the 10 th century Japanese female author, Lady Murasaki in mind: if the rare books written by her and a few other female authors had not survived in copies until modern times, we might assume that Japanese women were illiterate rather than the first authors of novels in the vernacular.

Beatriz de la Fuente led her colleagues to study the paintings of ancient Mexico. What is clear is that these studies will continue for generations, and scholars will turn time and again to the foundations established in the 20 th century. So many questions have yet to be asked. Some may be formulated from those asked in other parts of the world, and some questions for the ancient Greeks and Moche painters may even grow from what it is we come to think about the Maya.

Notas

1. David Stuart et al., "Early Maya Writing at San Bartolo Guatemala", Science, vol. 311, no. 5665, 2006, pp. 68-77. [ Links ]

2. Ramón Carrasco Vargas and Marinés Colón González, "El reino de Kaan y la antigua ciudad de Calakmul", Arqueología Mexicana, vol. 13, no. 75, 2005, pp. 40-47. [ Links ]

3. Christopher Donnan and Donna McClelland, Moche Fineline Painting: Its Evolution and its Artist, Los Angeles, University of California/Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1999. [ Links ]

4. Stelios Lydakis, Ancient Greek Painting and its Echoes in Later Art, Los Angeles, Getty Museum, 2004; [ Links ] M. Robertson, Greek Painting, Lausanne, Skira, 1959, pp. 122-127. [ Links ]

5. Duccio Bonavia, Mural Painting in Ancient Peru, Bloomington, Indiana University, 1985, pp. 47-71. [ Links ]

6. Donnan and McClelland, Moche Fineline Painting. [ Links ]

7. Walter Alva y Christopher Donnan, Royal Tombs of Sipán, Los Angeles, University of California/Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1993, p. 223. [ Links ]

8. Stuart et al., "Early Maya Writing". [ Links ]

9. Flora Simmons Clancy, Sculpture in the Ancient Maya Plaza: The Early Classic Period, Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 1999. [ Links ]

10. Ledyard Smith, "Guatemala: Excavations of 1931-1937", Washington, D.C., Carnegie Institution of Washington, no. 588, 1950. [ Links ]

11. Carrasco Vargas and Colón González, "El reino de Kaan". [ Links ]

12. C.C. Coggins, "Painting and Drawing Styles at Tikal: An Historical and Iconographical Reconstruction", Ph. D. dissertation, Massachusetts, Harvard University, 1975. [ Links ]

13. "We can be sure that the way the figures are composed on vases painted by contemporaries of Polygnotos are an accurate reflection of the trends in free painting", Lydakis, Ancient Greek Painting, p. 111. [ Links ]