Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

versión impresa ISSN 0185-1276

An. Inst. Investig. Estét vol.24 no.81 Ciudad de México sep./nov. 2002

Artículos

New Spanish Art in the Weddell Collection in Richmond, Virginia, USA: a Preliminary Catalog

Michael J. Schreffler

Virginia Commonwealth University

Resumen

Este artículo presenta un estudio y catálogo preliminar de un conjunto de obras de arte coleccionadas en México entre 1924 y 1928 por Alexander Weddell (1876-1948), cónsul general de los Estados Unidos de América, y su esposa, Virginia Chase Steedman Weddell (1874-1948). Mientras que otros extranjeros que conocieron el México de principios del siglo XX coleccionaron arte popular y obras de pintores contemporáneos, los Weddell se interesaron más en lo que llamaron "antigüedades". Su colección, que hoy en día pertenece a la Virginia Historical Society en Richmond, Virginia, EU, consta de varias obras del siglo XVIII, entre ellas una pintura de la Virgen de Ocotlán, un juego de pequeños lienzos ovalados con episodios del martirio de santa Inés, dos biombos —uno con una serie de escenas de caza y el otro con imágenes del Horatii Emblemata de Otto van Veen—, una parte de una sillería del coro, una escultura de la Virgen de los Dolores y varios textiles y obras de arte decorativo. Los Weddell reunieron su colección para decorar la "Casa Virginia", que posteriormente sería su domicilio permanente, asistidos en sus adquisiciones por René d'Harnoncourt, expatriado austriaco y corredor de arte. La escasa información sobre la procedencia de las obras se encuentra en Description of Virginia House, libro escrito por Alexander Weddell en 1947, y en la correspondencia entre Weddell y su esposa durante el periodo que residieron en México.

Abstract

This article presents a preliminary study and catalog of a group of art objects collected in Mexico by US consul general Alexander Weddell (1876-1948) and his wife, Virginia Chase Steedman Weddell (1874-1948), between 1924 and 1928. While other foreigners in early-twentieth century Mexico collected "folk" or "popular" art and the works of contemporary painters, the Weddells were more interested in what they called "antiques". Their collection, which today belongs to the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond, Virginia, US, consists of a number of works that date to the eighteenth century. They include a painting of the Virgin of Ocotlán, a set of small, oval canvases portraying episodes from the martyrdom of St. Agnes, two folding screens—one depicting a series of hunting scenes, and another with imagery derived from van Veen's Horatii Emblemata—, part of a choir stall, a carved image of theVirgin of Sorrows, and several textiles and works of decorative art. The Weddells assembled their collection to decorate "Virginia House", the home that later would become their permanent residence, and were assisted in their acquisition of the objects by Austrian ex-patriot and art dealer René d'Harnoncourt. Scant provenance data about the works in the collection appear in Alexander Weddell's 1947 Description of Virginia House and in volumes of correspondence between Weddell and his wife during the period of their residence in Mexico.

Alexander Wilbourne Weddell (1876-1948) served as US Consul General to Mexico from 1924 to 1928.1 His four-year tenure coincided with the presidency of Plutarco Elías Calles (1924-1928) and the us ambassadorships to Mexico of James Sheffield (1924-1927) and Dwight Morrow (1927-1930).2 Weddell and his wife, Virginia Chase Steedman Weddell (1874-1948), were fixtures in the high society of the North American and British "colonies" in post-Revolutionary Mexico City. They socialized regularly with the Sheffields and Morrows during their respective diplomatic assignments; they participated in the high-profile visits of goodwill ambassadors such as Will Rogers and Charles Lindbergh; and they befriended celebrated expatriots in Mexico like D.H. Lawrence and Zelia Nuttal.3

During his term, the Consul General and his wife rented a house in Mexico City's Zona Rosa at Calle Havre, No. 18. In a 1925 letter to a North American acquaintance, Alexander Weddell described their temporary residence in the capital city as idyllic and insular:

We have a pleasant home here with a bit of a garden, which my wife is enjoying supervising. There is a huge iron gate, which clangs behind one and shuts out the world as thoroughly as the portcullis which nearly trapped Marmion. We have luncheon on a terrace soaked in sunshine, and there is a tiny pool around which lilies are in full bloom now and then throughout the year.4

Virginia Weddell may indeed have enjoyed supervising her Mexico City garden, but by the following year, 1926, she had developed an even more consuming avocation: that of collecting what she and her husband referred to as "antiques." With the help of Austrian ex-patriot and art dealer René d'Harnoncourt, the Weddells assembled in their Zona Rosa home a sizeable collection of New Spanish paintings, sculptures, textiles and decorative arts, most of which dates to the eighteenth century. By 1928, at the end of the Consul General's tenure, the entire collection had been shipped north to Richmond, Virginia, USA, where the Weddells had built a country home they called Virginia House. An avid amateur historian, Alexander Weddell hoped that the Virginia Historical Society would make the house its headquarters in later years, and so in 1929, the Weddells bequeathed the house and its contents to that institution.5 Following Alexander and Virginia Weddell's untimely deaths in a 1948 train accident near St. Louis, Missouri, usa, Virginia House and its contents became the property of the Virginia Historical Society.

The years since their deaths have seen the production of some scholarship on the Weddells' lives, the construction of Virginia House, and its gardens, but their extensive collections of art and furniture have been virtually ignored.6 This article begins to fill that void by focusing on one sector of their collection: the works they acquired in Mexico in the 1920s. What follows below is a preliminary catalog of those objects prefaced by a brief examination of the circumstances of their acquisition. These findings are the result of a research seminar conducted in the spring of 2002 by graduate students in the Department of Art History at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.7 The article's dual aims are to bring these previously unpublished works to the attention of art historians in Mexico and elsewhere, and to contribute to the growing corpus of scholarship on art collecting by North Americans in early-twentieth century Mexico.8

The Weddells as Collectors in Post-Revolutionary Mexico

Alexander and Virginia Weddell collected art and furniture in the many places they lived and visited, including Mexico, India, Argentina, Peru, Spain, and England.9 The eclectic nature of the collection they assembled at Virginia House reflects the history of their travels and the cosmopolitan lives they led, but it also complements the imaginative style of the house itself, which incorporates the architecture of a twelfth-century priory the Weddells bought in England in the 1920s with that of two sixteenth-century English manor houses, and a loggia built with columns acquired in Spain.10 Construction on the house began in 1925 and was finished in 1928, a period that corresponds almost precisely to that of the couple's residence in Mexico City. It was, in fact, in the Mexican capital that the Weddells' architect, Henry Grant Morse, met with his clients to discuss his plans for Virginia House. Correspondence between the Weddells and Morse in this period suggests that the couple's collecting habits in Mexico were driven in large part by their vision for the house and its decoration. In keeping with the revival style and religious overtones of Virginia House, the Weddells sought to acquire art and furniture from previous centuries and, especially, works of a religious nature. For the Weddells, then, it was a happy coincidence that they found themselves in post-Revolutionary Mexico, where New Spanish art and furniture, much of which was religious in nature, was becoming increasingly available for purchase.

The Weddells' sharp focus on Spanish colonial art contrasted with the collecting habits of other foreigners in early-twentieth century Mexico. The easel paintings of Mexican "Indians" by Diego Rivera and his contemporaries were eagerly sought by vacationing tourist/collectors from the US,11 and ambassador Morrow and his family, whose period of residence in Mexico overlapped with that of the Weddells, joined a host of other North Americans in collecting "popular" or "folk" art.12 Although Weddells were mildly interested in folk art and acquired a few ceramic works, they had no interest whatsoever in the paintings of Rivera and his generation. Their disdain for contemporary art was a matter of their personal taste, but it was also based, at least in part, on their politics, as they saw the work of the Mexican painters of the 1920s as anti-American and closely allied with Bolshevism and the political Left. A 1927 letter from Alexander Weddell to the us State Department, for example, attests to the Consul General's perception of the radical political content of contemporary art in Mexico. In it, he criticizes the Mexican government's support of Rivera's murals at the Ministry of Education, claiming that their imagery included "visible expressions of contempt of and hostility to a neighboring country."13 Indeed, Weddell allied himself politically with other US citizens and officials in this period who believed that Mexico's foreign policy in the 1920s was "anti-American." He explained his view of the circumstances in a letter to his sisters. "There is nothing complicated about the Mexican situation," he wrote. "We have here a Bolshevik government, which is determined to get hold of the property of foreigners in the Republic and pay nothing for it."14

In his published works intended for a broader audience, however, Weddell's politics yielded to his passion for history and art. His 1947 Description of Virginia House, a publication that takes its reader on an illustrated tour of the couple's home in Richmond, is an important source for the study of the works the Weddells collected in post-Revolutionary Mexico.15 Following the example of his eighteenth-century British idol, Horace Walpole, Weddell set out in this publication to document the construction and contents of Virginia House for his friends and other interested parties.16 Weddell's art-historical bent is revealed in his preface to the Description, where he writes that one of his aims in documenting the objects in the collection is to give "where possible, an indication of their origin and place of purchase."17 Wed-dell recognized the historical value of the pieces in the collection, and he kept records on many of the couple's purchases. And while the Descriptions data on the Weddells' Mexican acquisitions are scant and sometimes questionable, they provide singular clues in the search for provenance information and, therefore, they are cited in the catalog below.

In some rare cases, the Description expounds on the couple's acquisition of an art object. Such is the case, for example, in his recounting of their 1941 purchase of a suite of marble columns in Granada, Spain and their 1940 discovery of a seventeenth-century genealogical chart in an antique shop in Seville.18

Those relatively lengthy passages in the text reveal that while it was Alexander Weddell who concerned himself with history and the keeping of records about the objects in the collection, it was Virginia Weddell who masterminded its assemblage.19

Personal letters exchanged between Alexander and Virginia Weddell from 1924 to 1928 confirm the latter's more active role in collecting art and furniture during the period of their residence in Mexico. Throughout the Consul General's tenure, the couple spent long periods apart, Alexander Weddell remaining in Mexico City while his wife traveled back and forth between Richmond, where she oversaw the construction of Virginia House, to Santa Barbara, California, where she received medical treatments at the Cottage Hospital. The Weddells were prolific correspondents, and their numerous letters and telegrams to one another, preserved in the archives of the Virginia Historical Society, frequently include Virginia Weddell's instructions to her husband on the purchase and shipping of her Mexican acquisitions.

Their correspondence indicates that in his wife's absence, Alexander Weddell served as the intermediary between Virginia Weddell and her art and antiques broker in Mexico, René d'Harnoncourt. In 1930, d'Harnon-court would organize the Mexican Arts exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and he later would become director of the Museum of Modern Art. At the time of Weddell's term as Consul General, however, he was a recent immigrant from Austria, having arrived in Mexico in 1926, where he sought and found work as an artist and antiques dealer.20 D'Harnoncourt's name first appears in the Weddells' correspondence and diaries in the fall of 1926, suggesting that Alexander and Virginia Weddell were among his first North American clients.21

In addition to scouting for art objects for the Weddells, d'Harnoncourt himself designed several works of decorative art which today form part of the collection at Virginia House. His profile portraits of Alexander and Virginia Weddell served as sketches for their wooden portrait medallions, carved in Mexico by Jesús Enríquez, which today adorn the entrance hall of Virginia House.22 He also designed the imagery for a carved oak plaque, produced in Mexico as well, which today hangs in the Weddells' library, and he constructed lampshades for lighting fixtures in the house from what appear to have been medieval manuscript folios.23

"The count," as the Weddells referred to d'Harnoncourt, was instrumental in the assemblage of their collection of New Spanish art, but their correspondence indicates other sources from which they acquired art and furniture as well. These include the antique shops that were magnets for collectors from the US in Mexico City in the 1920s: Sonora News, where d'Harnon-court eventually would work with Frederick Davis;24 Aztec Land; and Sanborn's. Alexander Weddell additionally refers in his letters to a shop at Calle Honduras, No. 45,25 the "funny old American who runs an antique shop over the crop shop opposite the Alameda"26 and the "thieves' market," which he describes as a "happy hunting ground for the person of antiquarian tastes."27

Despite the existence of a rich corpus of documents relating to the period of the couple's residence in Mexico City, the sources from which the Weddells acquired the works in their collection can in most cases only be surmised. It is hoped that future research will be able to shed light on the history of collecting practices in post-Revolutionary Mexico and the works from the collection of Alexander and Virginia Weddell.

Catalog of the Weddell Collection of New Spanish Art

I. Paintings

1. José María Montealegre, Virgin of Ocotlán, 1792. Oil and gilt on canvas, 96.5 cm X 75 cm (38 in X 29.5 in).

In his Description of Virginia House, Alexander Weddell erroneously believed this painting (fig. 1) to depict the Virgin of Guadalupe. He described it as follows:

Over an elaborately carved chest of drawers from Mexico is a painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Our Lady, who wears a royal crown and a gorgeous cope, is held aloft by cherubim; an enormous nimbus is behind [her] head and shoulders. Beneath is a rosary, displayed by cherubs, while others of these angelic attendants hold up medallions, each with a Latin inscription, illustrating the apparition of the Virgin to the poor Indian, Juan Diego.28

The subject of the painting is, in fact, Our Lady of Ocotlán. The canvas employs the conventional eighteenth-century iconography of her cult: a large, central image of the Virgin is surrounded by four smaller, oval medallions depicting her apparitions in 1541 to Juan Diego Bernardino.29 It includes a series of texts in Latin, some of which describe the images pictured in the medallions, and others which exalt the Virgin more generally. Beneath the central figure of the miraculous image of Ocotlán, and adjacent to the three cherubs that support it, the name José María Montealegre—presumably that of the painter—appears in red paint. The same pigment was used to write both the date, "año de 1792", on the medallion at the bottom right of the picture, and the damaged inscription across its lower edge, which reads, "[illegible] de D.n Leonotarsio y de su esposa D.ña sevastiana maria".

2. Artist(s) unknown, Episodes from the Martyrdom of St. Agnes, 18c. Oil and gilt on four oval canvases, each approximately 42 cm X 32 cm (16.5 in X 12.5 in).

Like the medallions in the corners of the painting of the Virgin of Ocotlán (fig. 1), these four, small oval paintings (figs. 2a, b, c, d) are interrelated and recount a religious narrative: that of the life and death of the third—or fourth—century virgin martyr St. Agnes of Rome.30

The first image in the series represents an early episode in Agnes' biography: her imprisonment in a brothel (fig. 2a). The Weddell canvas depicts a partially nude Agnes with bound wrists in an interior setting, where she is surrounded by a group of men. The diaphanous, cloudlike matter that covers her nude, upper body represents the fog or cloth that, according to some accounts, miraculously intervened to shield her from the onlookers. The second canvas (fig. 2b) also relates to the episode in the brothel, depicting Agnes on her knees, in prayer, as one of her aggressors lies injured on the ground, the apparent victim of an angel's wrath. The third painting in the series (fig. 2c) depicts the aftermath of the brothel scenes. According to both the Acts of the Martyrdom of Saint Agnes and the Golden Legend, the Romans, by order of Aspasius, attempt to kill Agnes by burning her on a pyre, but the saint remained untouched by its flames. The fourth image (fig. 2d) depicts Agnes' death by the sword. The Acts describe her death as having occurred by decapitation, while the Golden Legend reports that Aspasius, who previously had ordered her death by fire, later killed her by piercing her throat with a dagger. The Weddell canvas shows the kneeling martyr in prayer as her executioner drives a sword into her neck, causing a great stream of blood to fall to the ground.

Neither the original context of display for these works nor the source of their acquisition is evident. The canvases are not mentioned in Weddell's Description, but a 1928 inventory in the Weddells' papers shows that at the end of the Consul General's tenure, five small, oval paintings were shipped from Mexico City to Richmond. Four of these must have been the St. Agnes paintings, while the fifth must have been the crucifixion scene, described below (cat. no. 3; fig. 3). Their shipment from Mexico, together with a textual reference to the Colegio de Tepotzotlán on the crucifixion canvas suggest a Mexican provenance.

3. Artist unknown, Crucifixion with the Virgin and St. John, 18c. Oil on canvas, oval format, 44 cm X 33 cm (17.25 in X 13 in).

Nearly identical in size and shape to the St. Agnes canvases (figs. 2a, b, c, d) this image depicts the Virgin Mary and another figure, probably Saint John, flanking an image of Jesus Christ crucified (fig. 3). The dark background, together with artist's inclusion of the moon next to the body of Christ, suggest the artist's representation of the moment in the crucifixion narrative just before Christ's death on the cross, when, according to the scriptures, "a darkness fell over the whole land.. ."31

Beneath the image of the crucifixion is a text, which reads

Proprio Retrato, y medida. del S.to Xpto, qu

traxo pintado el demonio âvn hombre, de M.

illan conpacto dellebarse su alma, conlas ci

rcunstancias de traerlo, segunlevio en el.

Calvario, Oysevenera en Roma dh.a

Imagen; sacóseésta, delqestá en e

l Collegio de Theposotla.n

As noted above, documents in the Weddells' papers indicate the shipment of five small, oval canvases from Mexico City to Richmond in 1928. In the absence of other small, oval canvases in the collection, it is likely that the inventory was referring to this picture of the crucifixion and the four images of the martyrdom of St. Agnes. Apart from the difference in subject matter, the crucifixion scene diverges from the St. Agnes images in another way: the canvas on which it is painted is a more coarsely woven and, possibly, older cloth.32

4. After Miguel Cabrera, The Divine Shepherdess, 18-19c Oil on canvas, 102 cm X 82.5 cm (40.25 in X 32.5 in).

This canvas is nearly identical in its iconography, composition, and coloration to several of Miguel Cabrera's paintings of the Divine Shepherdess, of which Cuadriello notes there are at least six.33 In his Description, Weddell writes that the canvas was "bought in Mexico in 1927" and that "It hung for many years in an old convent for which it was perhaps painted."34

5. Artist unknown, St. Christopher and the Christ Child, 18c. Oil and gilding on canvas, 92 cm X 67 cm (36.25 in X 26.5 in).

The theme and iconography of this canvas (fig. 5) relate to accounts of the saint's life in hagiographies such as the Golden Legend, where Christopher is described as being "a man of prodigious size" who carried the Christ child across a river. The painting's composition, in which the saint dominates the canvas and is seen obliquely, with his head turned toward the child on his shoulders, echoes that of countless other images of Saint Christopher produced in Spain and the Americas in the age of Spanish imperialism. A Mexican provenance for the canvas is suggested in Weddell's Description, where he writes that it was "bought in Mexico in 1926."35 He provides no further information on the work. In a 1927 letter to Virginia Weddell, however, the Consul General reported to his wife from Mexico City that "René [d'Harnoncourt] came this morning: the paintings are at the house, also the photographs, also the painting of the Saint."36 The image of Saint Christopher and the Christ Child is the only work in the Weddell collection that could be described as "the painting of the Saint" and which, simultaneously, could have been acquired in Mexico. Thus, it is not unreasonable to hypothesize that Weddell was referring to this image in his letter to Virginia Weddell, and that d'Harnoncourt had a hand in its acquisition.

6. Miguel Cabrera(?), Virgin of the Rosary, 1760. Oil on oval canvas, 83 cm X 63.5 cm ( 32.75 in X 25 in).

An inscription placed prominently in the lower-right quarter of this oviform canvas (fig. 6) reads "Mich.l Cabrera. pinxt. ao. 1760," a signature phraseology and format similar to that on Cabrera's 1759 San Anselmo and his 1761 Agony in the Garden.37 Preliminary examinations indicate that the inscription is painted atop a layer of varnish, thus allowing for the possibility that it may be apocryphal.38

7. Artist(s) unknown, Biombo with Hunting Scenes, 18c. Oil on ten canvases, each approximately 185 cm X 53 cm (73 in X 21.25 in)

Of the unorthodox decoration of the Dining Room at Virginia House, Wed-dell wrote that

The West Wall is covered by what was once a ten-fold screen, representing an eighteenth-century hunting scene, probably the work of a Spanish artist. Men and animals are depicted in a style of naïve charm. This was bought in Mexico in 1926.39

The hunt may not have been among the most frequent subjects for pictorial biombos produced in the New World, but the Weddell screen (fig. 7) is not unique in its representation of the theme. A six-panel screen in the collection of the Museo Nacional del Virreinato in Tepotzotlán, for example, depicts a hunting scene on one of its two sides, as does its companion biombo in the Rodrigo Rivero Lake collection.40 Moreover, a screen produced in the Viceroyalty of Nueva Granada—today in the collection of the Museo Soumaya—depicts a hunting scene in front of a palace,41 and several biombos in published seven-teenth—and eighteenth—century censuses from New Spain are described as depicting similar themes of aristocratic leisure such as "montería."42

Apart from Weddell's own claim that the screen was "bought in Mexico in 1926," no firm documentary evidence of its provenance has been found in the couple's correspondence or shipping records. Letters exchanged between Alexander and Virginia Weddell in 1926 and 1927 contain several references to the packing of folding screens and their shipment from Mexico City to Richmond, but the Weddells acquired at least two and possibly three other biombos in Mexico. The references to screens in the correspondence do not include descriptions of the works, and, thus, it is impossible to know to which of the screens the Weddells were referring in any given letter.43 But in support of Weddell's claims to the Mexican provenance of the Hunting Scene biombo, it is noteworthy that it shares several characteristics with many of the screens produced in seventeenth and eighteenth-century New Spain, including its size, its composition of ten panels, and its use of a textured, gilded border around at least three of its edges.44

8. Artist(s) unknown, Biombo with Emblems from Otto van Veens Horatii Emblemata, 18c. Oil on canvas mounted on seven wood panels, each approximately 185 cm X 53 cm (73 in X 21.25 in).

This screen (fig. 8) originally consisted of at least ten panels, seven of which are presently in the Weddell collection at Virginia House.45 Each panel is uniformly divided into three rectangular sections framing distinct genres of imagery. The lower registers, which are the smallest of the three, depict ornamental swags of leaves and ribbons against a faux-marble background. The larger, central sections are more varied, representing architectural niches whose contents alternate between small, lidded urns on tall pedestals and long-necked vases that hold flower arrangements. Finally, the oval medallions in the upper registers frame imagery from Otto van Veen's Quinti Horatii Flacci Emblemata, a widely published seventeenth-century emblem book based upon quotations from the classical Roman poet, Horace.46

The provenance of the Weddell biombo is not provided in the Description, but the screen joins several others produced in eighteenth-century New Spain that take van Veen's Horatii Emblemata as their source. One of the latter is held in the collection of the Museo Soumaya in Mexico City; another was included in the 1994 exhibition Juegos de ingenio y agudeza, whose catalog documented it as belonging to the Galería de Antigüedades la Cartuja; and a third, smaller screen is in the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art in Dallas, Texas.47

II. Sculpture and Decorative Arts

9. Choir stall, c. 1700-1730. Mahogany, 138.5 cm X 218.5 cm X 62 cm (54.5 in X 86 in X 24.5 in).

Weddell's Description includes a relatively lengthy passage on the history and acquisition of this piece of church furniture (fig. 9). He writes that

The triple-seated choir stalls, with misericords, seen just below the sweep of the stairway [in the entrance hall], bear a shell motif over each seat [...] these stalls [...] were bought from the Martínez del Río family in Mexico City. They came originally from the Church of the Virgin of Guadalupe, built in the time of the Conquistadors. It is related that early in the last century [i.e., the 19th century] an archbishop of progressive ideas removed these seventeenth-century seats replacing them with something more modern!48

If Weddell's data on the provenance of these choir seats are accurate, then they may have come from the Old Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The relatively small size of their seat backs suggests that they may have come from the lower (rather than upper) register of a choir. Weddell's reference to the "misericords" is unclear; the stalls in their present condition do not incorporate such supports on the undersides of their hinged seats, nor do they show evidence of ever having included them. According to their correspondence, the couple was in possession of the stalls by October of 1926, when they had them packaged and shipped from Mexico City to Richmond.49

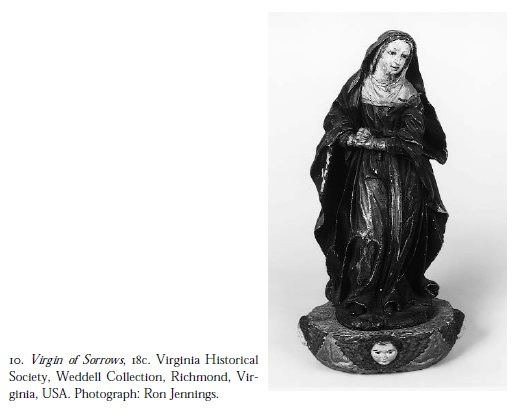

10. Virgin of Sorrows, 18c. Polychromed wood, 84 cm (33 in).

This small, wooden sculpture (fig. 10) follows the conventional iconography for the theme of the Virgin of Sorrows, representing a tearful Virgin Mary holding her hands together in prayer and dressed in red and blue robes.50

Her heart is pierced with a small, wooden dagger made of a separate piece of wood, which appears to be of distinct, possibly later manufacture than the sculpture itself. The faint remains of elaborate, gold patterning are visible on the back of the figure, thus suggesting that it may have originally borne extensive estofado on its robes. The date "MDXXV" (1525) is carved into the figure near her feet.

Weddell, in his Description, identified the image as representing the "Mater Dolorosa," a Latin designation for this advocation of the Virgin, and added that the sculpture was "found in Mexico."51 Correspondence between Virginia and Alexander Weddell in February of 1927 refers to their acquisition of a wooden figure of the Virgin Mary and indicates that it was cleaned and "refinish[ed]" by d'Harnoncourt.52

In addition to this image of the Virgin of Sorrows, the Weddell collection contains several other religious images in polychromed wood, including a representation of Saint Francis of Assisi that was, according to Weddell, also "acquired in Mexico."53 The provenance of the other sculpted works in the collection is unknown.

11. Two Pedestals, 18-19c Polychromed wood, each approximately 89 cm X 47 cm X 33.5 cm (35 in X 18.5 in X 13.25 in).

In his description of the "gallery," a room just outside the "state" bedroom on the main floor of Virginia House, Weddell notes the presence of two "wooden pedestals, painted in red and gold, with supporting eagles." He writes that the pieces were acquired "from a private chapel destroyed in the disorder of Mexico after 1911" and that "A[lexander] and V[irginia] bought them there in 1925." If this information is correct, then the pedestals would be among the Weddells' earliest documented acquisitions in Mexico. Moreover, the date given by Weddell indicates that their purchase could not have involved d'Harnoncourt, who did not arrive in Mexico until 1926.

12. Wall Hanging, 17-19c Red velvet, 615 cm (242 in).

Describing a particularly dramatic element of the decoration of the entrance hall at Virginia House, Weddell wrote that

From the roof of the hall, and partially concealing the entrance [...] hangs a Glorious sweep of ruby-red Genoese velvet of the 17th century [...] This was found in Mexico [...] [and may have been] one of a series of hangings used in a cathedral during festival seasons.54

The red velvet cloth that adorned the hall is one of hundreds of textiles in the Weddell collection, but it is the only one to which Alexander Weddell assigned a Mexican provenance in the Description. It is certain, however, that other textiles at Virginia House were also acquired in Mexico. Virginia Wed-dell was a tireless collector of patterned fabrics, linens, and ecclesiastical vestments, and references to her purchase of such objects during the couple's residence in Mexico abound in their correspondence. Those references reveal that, together with the help of her husband and friends, she searched for and found many such works at Sonora News and in other antique shops in Mexico City.55

13. Chandeliers, 18-19c Silver, wood, and gilding, various sizes.

The Weddells acquired at least four chandeliers in Mexico. One of these was hung in the room they called the "gallery" and was made of silver; Alexander Weddell wrote that it was "bought in Mexico in 1926" and that it was "made to carry eight candles..."56 The silver chandelier was subsequently fitted for use as an electric lighting fixture, as were the three others acquired in Mexico. These latter works now hang in the library at Virginia House. In the Description, Weddell describes them as "three wooden, gilded chandeliers of eighteenth-century workmanship." He adds that they were "found in Mexico in 1928"; that they were "originally fitted for candles"; and that they were "thought to have come from some religious establishment sacked during the Mexican Revolution following the expulsion of President Díaz in 1911."57 Correspondence between Alexander and Virginia Weddell suggests that they may have been purchased at Sanborn's.58

Notas

1. As Consul General, Weddell was charged with protecting the interests of us citizens in Mexico. He made frequent public speeches on international affairs, reported to the Secretary of State on economic and political conditions in the country, and kept records on North Americans residing and traveling in Mexico City. He outlined his duties as Consul General in "The American Consular Service", Mexican American 1, no. 40 (Feb. 28, 1925), p. 11. [ Links ]

2. Weddell served during Sheffield's ambassadorship, a time of strained diplomatic relations between the USA and Mexico, as well as during the first year of Morrow's tenure. On diplomats and diplomatic relations between the two countries in the 1920s, see Daniela Spenser, The Impossible Triangle: Mexico, Soviet Russia, and the United States in the 1920s, Durham, Duke University Press, 1999; [ Links ] Richard Melzer, "The Ambassador Simpático: Dwight Morrow in Mexico 1927-30", in Ambassadors in Foreign Policy: The Influence of Individuals on US-Latin American Policy, C. Neale Ronning and Albert P. Vannuci (eds.), New York, Praeger Publishers, 1987, pp. 2-27; [ Links ] James Horn, "El embajador Sheffield contra el presidente Calles", Historia Mexicana 78, no. 2 (Oct.-Dec. 1970), pp. 265-284. [ Links ]

3. On Virginia Weddell's presence at the Lindbergh landing, see Harold Nicholson, Dwight Morrow, New York, Arno Press, 1975, p. 313. [ Links ] On the Will Rogers visit, see Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 25 January 1927. References to D.H. Lawrence and Zelia Nuttal appear in the Weddells' correspondence, including Alexander Weddell to Doris Jones, 2 April 1925; and Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 27 March 1927. These and all subsequent references to the Weddells' correspondence refer to letters held in the Weddell papers in the Library of the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia, USA.

4. Alexander Weddell to "Tuck", 23 February 1925. Weddell's mention of "Marmion" refers to the title character in the novel by Sir Walter Scott, a copy of which was in Weddell's library at Virginia House (Sir Walter Scott, Marmion, Philadelphia, Frye and Kammerer, 1808).

5. Alexander Weddell, A Description of Virginia House in Henrico County, Near Richmond, Virginia, the Home of Mr. & Mrs. Alexander Wilbourne Weddell: Together with an Account of Some of the Furniture, Pictures, Curiosities, &c. Therein, With Illustrations of the Interior, the Exterior and the Surrounding Gardens, Richmond, VA, Virginia Historical Society, 1947, pp. x and 12. [ Links ]

6. Works on the Weddells and Virginia House include Robert L. Scribner, "Virginia House", Virginia Cavalcade 5 (Winter 1955), pp. 20-29; [ Links ] Elizabeth Cabell Dugdale, "Virginia House and Gardens", National Horticultural Magazine 36, no. 2 (April 1957), pp. 192-200; [ Links ] Irene Ruth Clancy, "The Relations Between the United States and Argentina during the Ambassadorship of Alexander W. Weddell, 1933-39", 1967 (M.A. Thesis, University of Virginia); [ Links ] Charles Raymond Halstead, "Diligent Diplomat: Alexander W. Weddell as American Ambassador to Spain, 1939-1942", Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 82, no. 1 (Jan. 1974), pp. 4-38; [ Links ] Halstead, "The Dispute Between Ramón Serrano Suner and Alexander Weddell", Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali 41, no. 3 (1974), pp. 445-471; [ Links ] Joyce MacDonald Glover, "Historic Attribution at Virginia House", Bulletin of the Virginia Historical Society 40 (June 1980), pp. 11-15; [ Links ] K. Richmond Temple, "Alexander Weddell: Virginian in the Diplomatic Service", Virginia Cavalcade 34, no. 1 (1984), pp. 22-39; [ Links ] Scott Burrell, "The Gardens of Virginia House", Bulletin of the Virginia Historical Society 53 (June 1986), pp. 1-4; [ Links ] Burrell, "Virginia House, A Growing Treasure", Bulletin of the Virginia Historical Society 64 (Spring 1989), pp. 1-3; [ Links ] Gary Inman, "Virginia House: An American Country Place", 1993 (M.A. Thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University); [ Links ] Heather Lynn Skilton, "A Tale of Two Houses, Transported: Virginia House and Agecroft Hall", 1997 (M.A. Thesis, University of Richmond). [ Links ] A painting in the collection believed by the Weddells to have been painted by El Greco is mentioned in Harold Wethey, El Greco and His School, Catalogue Raisonné, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1962, vol. 2, p. 256. [ Links ]

7. I am grateful to Bruce M. Koplin, former chair of the Department of Art History at Virginia Commonwealth University, for encouraging the undertaking of this project. At Virginia House, I thank Muriel B. Rogers, Curator, and Tracy Bryan, House Manager, for their enthusiasm and generous provision of access to the collection. I am indebted to the graduate students in my seminar—Jacqueline Carrera, Virginia Cofield, Dennis Durham, Emily Gerhold, Traci Horne, and Margaret Southwick— for the research they conducted on some of the objects catalogued in this article. I also thank Lorraine Brevig, who generously offered her expertise as a conservator, and Clara Bargellini, Charles Brownell, Barbara J. Johnston, Muriel B. Rogers, and an anonymous reader for the Anales who read and commented on drafts of the manuscript.

8. See Clara Bargellini, "El coleccionismo estadunidense", in México en el mundo de las colecciones de arte, Nueva España 2, Mexico City, Grupo Azabache, 1994, pp. 257-261; [ Links ] Bargellini, "Frederic Edwin Church, Sor Prudenciana y Andrés López", in Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, no. 62 (1991), pp. 123-138; [ Links ] James Oles, "South of the Border: American Artists in Mexico, 1914-1947", in South of the Border: Mexico in the American Imagination 1914-47, Washington, DC, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993, pp. 48-212; [ Links ] Rick A. López, "The Morrows in Mexico: Nationalist Politics, Foreign Patronage, and the Promotion of Mexican Popular Arts", in Casa Mañana: The Morrow Collection of Mexican Popular Arts, Susan Danly (ed.), Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 2002, pp. 47-63; [ Links ] Helen Delpar, The Enormous Vogue of Things Mexican: Cultural Relations between the United States and Mexico, 1920-1935, Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 1992. [ Links ]

9. In addition to his appointment in Mexico, Alexander Weddell also served as US Consul General to Zanzibar, Athens, Cairo, and Calcutta. In 1933, he was appointed US ambassador to Argentina, and in 1939 he was appointed ambassador to Spain.

10. On the design and construction of the house, see Weddell, op. cit.; Inman, op. cit.

11. Oles, op. cit., p. 110.

12. See Susan Danly (ed.), Casa Mañana: The Morrow Collection of Mexican Popular Arts, Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 2002; [ Links ] Danly, "The Morrows in Mexico: A Pictorial Essay", Hopscotch 2/4 (2001), pp. 86-107. [ Links ]

13. Alexander Weddell to Secretary of State, Mexico City, 20 October 1927, cited in Spenser, op. cit., p. 94.

14. Alexander Weddell to his sisters, Mexico City, 20 January 1927.

15. As in n. 5. The book was published in a limited edition of 350 numbered and autographed copies.

16. Weddell (p. x) refers explicitly in the text to Walpole and his publication, Description of the Villa... at Strawberry Hillnear Twickenham, Strawberry Hill, Thomas Kirgate, 1774. [ Links ]

17. Weddell, op. cit., p. XI.

18. Ibid., pp. 20 and 55.

19. Virgina Weddell's role in assembling the collection of art and antiques in Mexico echoes her very active involvement in the construction of Virginia House, which occurred during the couple's residence in Mexico. See Inman, op. cit., p. 15.

20. On d'Harnoncourt in Mexico, see Geoffrey T. Hellman, "Imperturbable Noble", New Yorker 36, no. 12 (May 7, 1960), pp. 49-112; [ Links ] René d'Harnoncourt, 1901-1968: A Tribute, New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1968; [ Links ] Delpar, op. cit., p. 66; Oles, op. cit., p. 123-131; Susan Danly, Casa Mañana. , pp. 95-97. [ Links ]

21. Among his other clients were Ambassador Morrow and his family. On d'Harnoncourt's relationship with the Morrows, see also Delpar, op. cit., pp. 66 and 134; Oles, op. cit., pp. 127-133, Danly, op. cit., pp. 95-97.

22. Weddell, op. cit., p. 32.

23. Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 26 October 1926; Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 30 October 1926; Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 21 January 1927; Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 30 January 1927; Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 7 February 1927.

24. See Hellman, op. cit.; Delpar, op. cit., p. 66; Oles, op. cit., pp. 123-125.

25. The names of these shops appear in the Weddells' correspondence. See, for example, Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 24 February 1929; Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 2 March 1927; Virginia Weddell to Alexander Weddell, 24 January 1927; Virginia Weddell to Alexander Weddell, 13 January 1927.

26. Alexander Weddell to Emma Lewis, 24 November 1928.

27. Alexander Weddell to Joseph C. Grew, 27 October 1927.

28. Weddell, op. cit., p. 75.

29. The apparitions are recounted in Manuel de Loayzaga, Historia de la milagrosísima imagen de Nuestra Señora de Ocotlán, Puebla, Viuda de Miguel Ortega, 1745. [ Links ] On the eighteenth century iconography of Virgin of Ocotlán, see Jaime Cuadriello, "Tierra de prodigios: La ventura como destino", in Los pinceles de la historia. El origen del reino de la Nueva España, 1680-1750, Mexico City, Museo Nacional de Arte, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1999, pp. 201-211. [ Links ]

30. On the life of the saint, see St. Ambrose, De Virginibus, I, 2; Prudentius, Peristephanon, Hymn 14; Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend, trans. Granger Ryan and Helmut Rip-perger, New York, Arno Press, 1969, pp. 110-113.

31. See Matthew 27:45; Mark 15:33; Luke 23:44.

32. Lorraine Brevig, Richmond Conservation Studio, personal communication, January 2002.

33. Jaime Cuadriello, Catálogo, p. 68; cf. Guillermo Tovar de Teresa, Miguel Cabrera: Pintor de cámara de la reina celestial, Mexico City, InverMéxico Grupo Financiero, 1995. On the Weddell canvas, see Marybeth Rabung, "La Divina Pastora, A Vision of Paradise", 1987 (M.A. Thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University).

34. Weddell, op. cit., p. 61.

35. Ibid., p. 56.

36. Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 4 February 1927.

37. Inscriptions reproduced in Abelardo Carrillo y Gariel, El pintor Miguel Cabrera, Mexico City, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1966, p. 46. [ Links ]

38. On apocryphal signatures on New Spanish paintings, see Jaime Cuadriello, "Imposturas y ficciones colonialistas", Artes de México, no. 28 (1995), pp. 40-49. [ Links ]

39. Weddell, op. cit., p. 48.

40. On these two screens, see Salvador Moreno, "Un biombo mexicano del siglo XVIII", Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, no. 28 (1959), pp. 29-32; [ Links ] Antonio Bonet Correa, "Un biombo del siglo XVII", Boletín del INAH, no. 21 (Sept. 1965), pp. 33-37; [ Links ] Manuel Toussaint, Colonial Art in Mexico, trans. Weismann, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1967, p. 392; [ Links ] Marta Dujovne, Las pinturas con incrustaciones de nácar, Mexico City, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1984, p. 101; [ Links ] Virginia Armella de Aspe, "La influencia asiática", in La concha nácar en México, Mexico City, Grupo Gutsa, 1990, pp. 89-90; [ Links ] Rodrigo Rivero Lake, Visión de un anticuario, Mexico City, Landucci, 1997, pp. 284-285; [ Links ] Schreffler, "Art and Allegiance in Baroque New Spain", 2000 (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago), pp. 248-249. [ Links ]

41. María Teresa Espinosa Pérez, "Constelación de imágenes: en los confines del viento", in Viento detenido: mitologías e historias en el arte del biombo, Mexico City, Asociación Carso, 1999, pp. 237-246 [ Links ]

42. See Manuel Toussaint, "Las pinturas con incrustaciones de concha nácar en la Nueva España", Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, no. 20, vol. 5 (1952), pp. 10-12; [ Links ] Gustavo Curiel, "Relación de descripciones de biombos que aparecen en documentos notariales de los siglos XVII y XVIII", in Metodologías e historias en al arte del biombo. Biombos de los siglos XVIII-XIX en la colección del Museo Soumaya, México, Grupo Carso/M.S., 1999, pp. 24-32. [ Links ]

43. Virginia Weddell to Alexander Weddell, 14 May 1926; Virginia Weddell to Alexander Weddell, 31 October 1926; Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 5 November 1926; Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 9 November 1926.

44. Schreffler, op. cit., pp. 138-142.

45. Three other panels belonging to this screen are held in a private collection in Charlottesville, Virginia.

46. Otto van Veen, Horatii Emblemata, Stephen Orgel (ed.), New York, Garland Publishing 1997. [ Links ]

47. Santiago Sebastián, Iconografía e iconología del arte novohispano, Mexico City, Grupo Azabache, 1992, pp. 150-157; [ Links ] Marita Martínez del Río de Redo, "Los biombos en el ámbito doméstico: sus programas moralizadores y didácticos", in Juegos de ingenio y agudeza: la pintura emblemática de la Nueva España, Mexico City, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1994, pp. 142-43; [ Links ] Dallas Museum of Art: A Guide to the Collection, Dallas, Dallas Museum of Art, 1997, p. 206; [ Links ] Viento detenido, pp. 195-206. [ Links ]

48. Weddell, op. cit., pp. 33-34.

49. Virginia Weddell to Alexander Weddell, 31 October 1926.

50. See Carol M. Schuler, "The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin: Popular Culture and Cultic Imagery in Pre-Reformation Europe", Simiolus 21, nos. 1-2 (1992), pp. 5-28. [ Links ] On the iconography of the Virgin of Sorrows in New Spain, see Jaime Cuadriello, "Mater Dolorosa", Memoria, Museo Nacional de Arte 7 (1998), pp. 96-97. [ Links ]

51. Weddell, op. cit., p. 65.

52. Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 4 February 1927; Alexander Weddell to Virginia Weddell, 7 February 1927; Virginia Weddell to Alexander Weddell, 14 February 1927.

53. Weddell, op. cit., p. 65.

54. Ibid., p. 36.

55. Alexander to Virginia Weddell, 24 February 1927; Virginia Weddell to Alexander Weddell, 11 November 1926; Virginia Weddell to Alexander Weddell, 22 January 1927.

56. Weddell, op. cit., p. 58.

57. Ibid., p. 69.

58. Virginia Weddell to Alexander Weddell, 24 January 1927.