Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

versão impressa ISSN 0185-1276

An. Inst. Investig. Estét vol.23 no.79 Ciudad de México Set./Nov. 2001

Artículos

Made for the USA: Orozco's Horrores de la Revolución1

Anna Indych

University of New York

Abstract

This paper traces the development of a series body of drawings by José Clemente Orozco known upon their commission as Horrores de la Revolución (The Horrors of the Revolution, 1926-1928), and their relation to his murals at the National Preparatory School, in terms of the political pressures on Mexico's post-revolutionary regime and the demands of the New York art market

Resumen

Este trabajo bosqueja el desarrollo de una serie de dibujos de José Clemente Orozco conocidos desde el momento que fueron encargados como Horrores de la revolución (1926-1928), y su relación con los murales de la Escuela Nacional Preparatoria. Todo ello en terminos de las presiones políticas sobre el régimen posrevolucionario y de las demandas del mercado del arte en Nueva York.

What seems to be the eternal violence of the civil war in Mexico spills out in the crude and raw, yet delicate ink and wash drawings by José Clemente Orozco, known upon their commission as Horrores de la Revolución, and later, in the United States, entitled Mexico in Revolution. One of the lesser known works from the series, The Rape, in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, exemplifies Orozco's horrific vision of the Revolution. In a ransacked room, a soldier mounts a half-naked woman, pinning her down to the floor by her arms and hair. He perpetuates a violation committed by the other figures leaving the room—one disheveled soldier, viewed from the back, lifts his pants to cover his rear as a shadowy figure exits through the parted curtains to the right of the drawing. Bottles of alcohol, as well as the soldiers' hats, a rifle and a cane are strewn about the floor. A chair teeters over; a painting and a hanging mirror have been knocked asunder; and the glass door of the armoire is shattered. The dynamic zig-zag lines utilized by Orozco to represent the glass reflections of the hanging mirror and the armoire door heighten the tension and volatility of the scene. A brutal image of biting realism, The Rape, like many other drawings in the series, is an unprecedented visualization of the struggles and upheaval of the Revolution.

Painted on many public walls in Mexico, the Revolution finds perhaps its most primal visual form in these small-scale, intimate drawings. The development of Orozco's unique series within the context of the political pressures of the post-revolutionary regime and the demands of the New York art market is the subject of this paper.

Made to order in 1926 while Orozco was still in Mexico, the series is based on events the artist had witnessed over ten years prior to their making. According to Jean Charlot, the bulk of the series was made in Mexico and only a few new drawings and duplicates were added in New York.2 Regardless of where they were created, all of Orozco's Horrores drawings were made expressly for an audience north of the border.

The commission began as six drawings meant to illustrate a book about the Revolution to be published in the United States. As a way to help Orozco during difficult financial times, Anita Brenner, writer, journalist, and energetic supporter of Mexican artists, invented "a mythical gringo' patron.3 Orozco must have been aware of the conceit of Brenner's commission early on, yet continued, upon her suggestion, to develop the series despite the phantom patron and bogus context for the work. Though Brenner concocted the North American client to aid the artist, the circumstances of the actual patronage were not so different.

Brenner, though born in Mexico, grew up and studied in the United States. At the time of the commission she was busy preparing a book in English on Mexican art that would eventually become her magnum opus, Idols Behind Altars.4 Even though Idols is not a book about the Revolution, the civil war plays a prominent role in the narrative. While Brenner intended to mask her patronage in fear that Orozco would not accept money from her, the well-intended ruse turned out to be rather transparent. She in essence was the gringa client who had her own book in mind when commissioning the drawings. In the end, several images from the series were featured in Brenner's publication.

At the time Brenner commissioned the drawings from Orozco, he had already begun the second phase of work on the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria murals, which relate both formally and thematically to the Horrores series. Accommodating the monumentality of the murals in a small-scale format, the drawings carry forward some of the general themes begun on the third floor of the enp. Some of the iconographic elements shared between the murals and the drawings are: soldiers preparing for or returning from battle, grave diggers, torn maguey plants, as well as blank architectural backdrops.

What I would like to emphasize here, however, is rupture and not continuity. While there is a tendency to group all of Orozco's work with revolutionary themes into a cohesive entity, the Horrores are a breed apart. Though they relate to the third floor murals of the Preparatoria, the drawings propose a very different viewpoint of the Revolution.

The third floor Preparatoria murals painted during the post-Revolution, an era of consolidation, evoke a temporally abstract notion of the civil war. Debates remain to this day as to whether the scenes depict moments before or after the Revolution. Are the workers leaving or returning home? Are the soldiers returning from or preparing for battle? Three panels out of the entire mural cycle—The Trinity, The Trench and Revolutionaries—are the only scenes where armed struggle is even suggested by the inclusion of weapons and guns. Only one of these three panels, Revolutionaries, is part of the cohesive third floor that has been compared to the Horrores. The rest of the six panels on the third floor evoke the Revolution through more oblique means: the impact on the land, the implicit sacrifices of war, and the separation of families. Armed struggle, indeed struggle in any sense of the word, is not signified. As others have commented, Orozco's unified statement about the civil war is a muted drama which evokes restrained and subdued emotions with little emphasis on direct action.5 "The rigidly controlled structure," sense of balance, "the three dimensional clarity of the individual forms, and the serene strength of the blue background" lead American author Bernard Myers to call the cycle in 1956 a "summing up of Orozco's classical phase."6 This kind of representation could not be further from the realities of the Horrores drawings.

While the Preparatoria scenes manifest an understated sense of drama, an overall static quality, and a sense of controlled emotion, the Horrores, as a series, represents sheer brutality and bloodshed; the drawings are tragic, expressive, aggressive, and abject. Many graphically depict blood, body parts, intense drama, emotional and physical suffering, as well as overt action. Significantly, the carnage of the Revolution is enacted on the human body which is depicted as vulnerable, fragmented, and dislocated.

Among the drawings that most graphically display corporeal devastation are Mutilated and The Wounded, images of temporary field hospitals filled with disfigured and amputated soldiers. Piles of dead bodies abound in several other drawings. Battlefield No. 1 and Battlefield No. 2 each show two bodies at the bottom of a hill crowned by the image of a torn, ripped maguey plant. The bodies are so flat, they seem to be eviscerated of skeleton and bone, appearing as lumps of flesh lining the hill. Each drawing includes the form of a hat that sits in volumetric repose to the formless bodies.

Under the Maguey, a similar composition, contains two figures beneath a cactus. A sharp knife held in the stiff hands of the central corpse provides the focus of the image and mimics the tactile sharp tendrils of the cactus above. The dead body to the right of The Destroyed House is stabbed in the back with a knife and the rape scene to the left of the image is almost the mirror-image of the one depicted in The Rape.

Common Grave is a conglomeration of fragmented body parts while Dynamited Train on the right depicts three naked figures. In the foreground, one of the women crouches on her knees with her upper body slouched forward. Her head is covered by a piece of corrugated metal, from which blood drips down her body in a pattern that formally mirrors the corrugation. Drops of blood coagulate at her elbow and at her nipple.

With a biting realism, Orozco visualizes the sheer brute force and violence of the Revolution. Workers stage a violent strike, a train is held up at knife point, houses and churches are looted, enemies kneel before the firing squad and armed forces clash head-on in a battle that sees no victor. José Juan Tablada who saw the series in New York vividly suggested that "blood continued to flow from the drawings; that smoke from the fires was immobilized in them and that they made the acrid odors of the battle endure."7 His statement suggests their graphic potency made contemporary Mexican viewers relive the Revolution.

The drawings are explicit in a way the murals are not. Unlike the ambiguous temporal location of the Preparatoria scenes, the Horrores clearly depict the Revolution, not moments before or after. Bodily carnage and physical pain, effaced in the murals, are "brought back with graphic certainty" 8 in the drawings. Octavio Paz has described, in reference to the drawings, how Orozco "made mock of the Revolution as an idea and found it repellent as a system and horrifying as a power."9 In an era when the Revolution needed to be legitimized, then, Orozco's critique could only be developed in small-scale drawings meant for export, not in the public murals of Mexico City.

The capacity of the drawings to make one viscerally experience the Revolution and to provoke intense emotive responses, has lead to speculations about their social function. In the United States they have been seen as a force for political change. Calling them "little 'painted bibles,'"Alma Reed interpreted them as moralistic tales "unshaken in their demand that we abandon the ways of the jungle."10 Myers contended that "Orozco had a definite utilitarian purpose in mind... [and that the series] was done for immediate and practical use."11 Myers did not realize the drawings were never meant for a Mexican audience. As the drawings were made, Orozco delivered them to Brenner who held onto them until they were brought to the United States. They were destined, from their inception, for an audience north of the border far removed from the political realities of the post-revolutionary period. The circumstances of their production made social change least desirable.

Moreover, the drawings represent a standard middle class viewpoint of the Revolution—a mixture of disdainful despair and morbid fascination with the sheer carnage of the civil war—a viewpoint shared by intellectuals such as Orozco and his friend Mariano Azuela, author of the famous revolutionary novel Los de abajo12- Orozco and Azuela shared a vision of the Revolution as an inevitable, natural upheaval. The one certainty of the Revolution was death; the specifics of the civil war—the programs, leaders, and factions—mattered little in the face of an oppressive, inescapable, human catastrophe. Such a vision of the Revolution precludes the idea that Orozco desired to effect any particular change with his series. Though these images represent a compassion for the oppressed and are an invective against social injustice, Orozco did not aim to direct behavior because he did not think it was possible. The whole point of the series is that we are condemned to a power beyond our control.

The Horrores commission and Brenner's support of Orozco fell within her larger plan to bring an awareness of Mexican art to the United States. From the beginning, she pushed Orozco to create enough for an exhibition. Once Brenner arrived in New York in 1928 she showed the Horrores to numerous gallerists, dealers, and critics with the hope of securing an exhibition for the series. Yet, the plan failed as the drawings were not well received. Years later she remarked: "At that time, the Mexican painters were so little known that I got a rather odd reception, and it was pointed out to me that these things weren't really art, they were drawings and cartoons suitable for the New Masses, and I was seriously advised by an art dealer who is now one of the Orozco 'Discoverers' to take them to that magazine."13

The Horrores drawings, then, were not considered "fine art" but political caricatures by the New York art community. J.B. Neumann of the New Art Circle not only questioned their status as art, but also suggested to Brenner that they were "insulting to lovers of pure art."14 Frank Crowninshield of Vanity Fair dismissed the drawings while Pierre Matisse disparaged all Mexican art as illustrative.15 Even Walter Pach, who had included Orozco's water-colors of prostitutes in the Independents exhibition of 1923 in New York and would later pay tribute to Orozco's art, found the drawings "heretical" and "not pure art, but illustrative."16 Attuned to the style and subject matter of Cubism and European modernism, in general, New York gallerists must have considered Orozco's social realism contrary to current aesthetic tastes. The influx and dominance of French art at the time played into the skewed reception of Orozco's drawings.

Though Brenner received some positive feedback from the Anderson Galleries and deposited a few of the drawings at the Weyhe Gallery on consignment, no exhibition organized by her ever materialized. The mainstream art galleries of New York decided the subject matter of the drawings made them suitable for the social criticism and political cartoons of the radical Marxist magazine New Masses but not mainstream consumption.

Though the drawings were created by Orozco for an audience supposedly removed from the historical realities of the civil war in Mexico, the artist was not any freer to represent the Revolution in the United States. When they were finally publicly displayed, through the efforts of Alma Reed, at the Marie Sterner Galleries in New York in 1928 as the Mexico in Revolution series, the drawings launched the season to virtually no reviews. With regard to the violence of the images one guest had asked Tablada "why do Mexicans do this?" To which he responded, "It isn't Mexicans who do this... but all men..."17 The clientele of the Marie Sterner Galleries interpreted the drawings according to the then ubiquitous stereotype of Mexicans as violent bandits. Reed later stated that "It was obvious. fashionable Manhattan had not yet developed an interest in Mexican tragedy—or in tragedy of any nationality. Most of the guests expressed considerably more interest in Mrs. Sterner's collection of Biedermeier furniture than in Orozco's portrayal of revolutionary violence."18 Years of anti-Mexican rhetoric in the press, and strained relations between the two countries as a result of the events of the Mexican Revolution, generated a rather inhospitable climate for the debut of Orozco's revolutionary drawings in the United States.

Even the linguistic turn of phrase, a shift in title from Brenner's more forceful "horrors of the Mexican Revolution," to the more benign "Mexico in Revolution" did not make the series any more palliative. Though the Sterner title evacuated the series of its immediate visceral significations, a more drastic measure needed to take place in order for the Horrores to garner more widespread appeal in the United States.

Due to the lack of immediate success with the Horrores series, Orozco turned to lithography as an immediate solution to his financial problems and as a long term strategy to give him the exposure needed to bring him mural commissions in the United States. In early 1928, the artist assured his wife that if "the 'horrores,' had been printed instead of drawn," he "would have already sold many."19 Thus, with the idea of conquering the art scene in the United States, Orozco began to make lithographic versions of the Horrores.

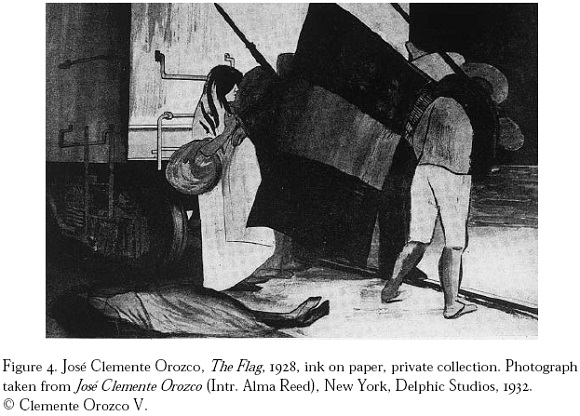

The Flag was the first of the Horrores series to be turned into a print. The lithographic version of the drawing departs from the drawn original in several significant ways. Orozco cropped the somber image of dejected soldiers and soldaderas walking across train tracks with bowed heads while carrying a large flag, to eliminate the prone figure splayed across the railroad tracks in the lower left foreground of the composition. The lithograph focuses instead on the group of walking figures, which was skewed slightly to the right of the drawing so that the huge flag is now centralized. Because Orozco expunged the dead figure and cropped the whole composition, the central group of figures now fills most of the composition. The artist's formal changes monumentalize the figures and cause the flag to occupy a third of the image. The flag, part of a broader narrative in the drawing, overwhelms the composition and the transformed image thus comes to suggest nationalistic sentiment. In addition, Brenner had entitled the original drawing The Flag Bearer, emphasizing its human element. Reed's title The Flag, shifted attention away from the figures and to the flag itself. The meanings produced by the lithograph therefore deviate significantly from the critical stance and anti-revolutionary fervor of the original drawing and the series as a whole.

From the entire Horrores series, Orozco made lithographic versions of four drawings; following The Flag he produced Requiem, 1928; Ruined House, 1929; and Rear Guard, 1929. Though these three lithographs remained more faithful to the original drawings, they did not need to be cleansed in the manner of The Flag. All three images closely relate to the murals on the third floor of the enp. The departing backs of soldiers and soldaderas in Rear Guard echo those of the Revolutionaries panel of the Preparatoria; the huddled forms of the peasant women in Ruined House echo similar figures in The Family, while the foreground figure of the man lying down on his side is a variation of the Gravedigger. Like Rear Guard, Requiem depicts the backs of mourners and reflects the general mood of the third floor mural panels. The somber, brooding tone of these images remains more tranquil and pensive than the Horrores focusing on the atrocities of war.

Orozco's reworked Horrores found immediate critical and commercial success, and brought the series out of the darkness. The American Institute of Graphic Arts chose Requiem as one of the best fifty prints of 1928. Walter Pach, who only a year earlier had considered the Horrores heretical, was the juror who helped make the selection. Orozco himself noted that "This lithograph has been a stupendous success, everyone has liked it and the newspapers have spoken very well of it."20 In April 1929 Orozco wrote his wife: "The success continues! The Weyhe Gallery... wants me to make more lithographs. I have only made three. in all the days of my life and they have already given me fame and money."21 In July 1929, Requiem appeared in a group print exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art along with prints by old and modern masters such as Michelangelo, Durer, Rembrandt, Picasso, and Matisse. The critic for the New York Evening Post found Flag and Requiem "dramatic, yet without any forcing of... emotional appeal."22

Only those drawings bearing more of a direct relationship with the Preparatoria murals, the more classic, serene, less brutal scenes, were turned into lithographs. The real "horrors"—those drawings graphically depicting violence, bodily injury, and blood—were virtually repressed. In effect, what happened to the series by the shift in title, the isolation of individual drawings from the entirety of the series, and the choices made to promote certain images through lithography, is that it became another way of representing "lo mexicano." Stereotypical subject matter—peasants, maguey plants, soldaderas—were emphasized, but the horrific vicissitudes of the civil strife and the struggles of the Mexican people would be sanitized from the series in order to effect its commercial debut in the United States. Neither the public in Mexico nor the United States in the late 1920s was ready for Orozco's horrific portrayal of revolutionary violence.

Notas

1. This paper was presented as a lecture for a scholarly symposium held in conjunction with the exhibition "José Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927-1934" at the San Diego Museum of Art in March 2002. Many thanks to Betti-Sue Hertz for her invitation to participate in the conference and to Renato González Mello for making the publication of this paper possible. The research and ideas presented here originate from a much broader and detailed chapter of my doctoral dissertation, "A Mexico for Export: Mexican Art and Artists in the United States, 1927-1940." I would like to thank my advisors, Professor Edward J. Sullivan and Professor Robert S. Lubar for their invaluable mentorship and support. I am also grateful to Susannah Glusker who so generously made accessible the diaries of her mother, Anita Brenner; Professor Kenneth E. Silver for his esteemed wisdom; and Lynda Klich for her astute editorial assistance.

2. Jean Charlot, "Orozco's Stylistic Evolution," in Charlot, An Artist on Art (Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 1970), p. 287. Originally published in College Art Journal 9, no. 2 (Winter 1949-1950), pp. 148-157. [ Links ]

3. Ibid.

4. Anita Brenner, Idols Behind Altars (New York: Payson and Clarke, 1929). [ Links ]

5. Leonard Folgarait, Mural Painting and Social Revolution in Mexico, 1920-1940: Art of the New Order (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 63-71. [ Links ]

6. Bernard S. Myers, Mexican Painting in Our Time (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956), p. 94. [ Links ]

7. José Juan Tablada, El Universal, 21 October 1928. (Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own.)

8. Folgarait, Mural Painting and Social Revolution in Mexico, p. 7. [ Links ]

9. Octavio Paz, "The Concealment and Discovery of Orozco," in Paz, Essays on Mexican Art, trans. Helen Lane (New York, San Diego and London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1993), p. 188. Originally published in Vuelta (Mexico City) 10, no. 119 (October 1986). [ Links ]

10. Alma Reed, Orozco (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956), p. 41. [ Links ]

11. Myers, Mexican Painting in Our Time, p. 53. [ Links ]

12. In 1929 Orozco illustrated the English translation of Mariano Azuela s Los de abajo: The Under Dogs: A Novel of the Mexican Revolution, trans. E. Munguia, Jr. (New York: Brentanos, 1929).

13. Anita Brenner quoted in Charlot, "Orozco's Stylistic Evolution," p. 286. [ Links ]

14. Anita Brenner diaries, 20 October 1927, courtesy Susannah Glusker, Anita Brenner Estate.

15. Ibid., 20 December 1927 and 10 January 1928.

16. Ibid., 19 November 1927.

17. Tablada, El Universal, 21 October 1928.

18. Reed, Orozco, pp. 77-79.

19. Orozco to Margarita V. de Orozco, 14 March 1928, Cartas a Margarita (México, Era, 1987), p. 104.

20. Ibid., 29 March 1929, Cartas, pp. 152-53.

21. Ibid., 20 April 1929, Cartas, p. 157.

22. Margaret Breuning, The New York Evening Post, 7 January 1928 (Weyhe Gallery Scrap-books, Volume III, p. 156, Weyhe Gallery Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution). [ Links ]