Introduction

Our interest in Boniface Augustin Lucien, called Auguste, Ghiesbreght (1812–1893) arose from amphibians and reptiles reputedly collected in Oaxaca, and in particular the disputed origin of the holotype of Coryphodon oaxaca Jan, 1863, a Racer (Coluber constrictor oaxaca) described from “Mexique” but obtained in the eponymous state according to contemporary French herpetologists (e.g., Duméril et al., 1854a, see Table 1).

Table 1 MNHN-RA amphibians and reptiles reputedly collected by Auguste Ghiesbreght in “Oaxaca”: Verbatim registration in catalogue of acquisitions, taxon and accession number of respective specimen or series (type status if applicable), and early published records.

| Ledger entry | identity | reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1842 – “d’Oaxaca, au Mexique” from M.[onsieur] “Ghuisbreght” [sic] – amphibians (Hylidae, Plethodontidae) and lizards (Phrynosomatidae) | ||

| “Hyla Baudinii” | Smilisca baudinii (Duméril & Bibron, 1841) MNHN-RA 4799 | Brocchi (1881: 30, Hyla Baudini [sic]), various specimens (“de nombreux exemplaires”) from “Mexique” incl. MNHN-RA 4799 |

| “Geotriton mexicanus” | Pseudoeurycea gadovii (Dunn, 1926) MNHN-RA 4749 (five specimens) | Duméril, Bibron & Duméril (1854c: 94 f., Pl. 104, Bolitoglossa mexicana), all five “Oaxaca“ specimens without type status (“peut-être […] autre espèce”) |

| “Tropidolepis variabilis seu aeneus” | Sceloporus variabilis Wiegmann, 1834 MNHN-RA 3056 (two specimens) | Duméril & Duméril (1851: 77, T.[ropidolepis] variabilis), “Oaxaca: M. Ghuisbreght” |

| “Microlepidotus (Tropidolepis)” | S. grammicus microlepidotus Wiegmann, 1828 MNHN-RA 3152 (six specimens) | Duméril & Duméril (1851: 77, Tr. Microlepidotus), “Oaxaca (Mexique): M. Ghuisbreght”; Duméril (1856: 548), “du Mexique par […] M. Ghuisbreght” |

| ibid. – snakes (incl. Colubridae, Dipsadidae, Natricidae) | ||

| “Coronella spec. nov.” | Lampropeltis cf. polyzona Cope, 1860 MNHN-RA 0419 | Duméril et al. (1854a: 623, Coronella doliata (Linnaeus, 1766) [suppressed name]), “Oaxaca par M. Guisbreght”, see text |

| “Dipsas nebulosa” | Sibon dimidiatus (Günther, 1872) MNHN-RA 7297 | Duméril et al. (1854a: 468, Petalognathus nebulatus (Linnaeus, 1758)), “Mexique […] Variété D […] par […] Ghuisbreght”; Mocquard (1908: 882), see text |

| “Lycodon ?” | specific allocation and specimen (1) unknown | see text |

| “Psammophis ?” | Coluber constrictor oaxaca (Jan, 1863) MNHN-RA 7378 (holotype) | Duméril et al. (1854a: 184, Coryphodon constrictor (Linnaeus, 1758)), “d’Oaxaca, par M. Ghuisbreght”; Jan (1863: 63), “Mexique”; Bocourt (1890: 697, 701–02, Pl. 48.2, Bascanion oaxaca), “rapporté d’Oaxaca (Mexique)”, see text |

| “Tropidonotus saurita” | Thamnophis sp. (spp.?) unlocated (six specimens) | Duméril et al. (1854a: 587, Tropidonotus saurita (Linnaeus, 1758)), incl. “Ghuisbreght […] recueilli à Oaxaca, dans le Mexique”, see text |

| 1845 – “d’Oaxaca (Mexique)” from M.[onsieur] “Ghisbregcht” [sic] – lizard (Corytophanidae) and snakes (incl. Xenodontidae) | ||

| “Saurien voisin du G.re Polychrus” | Laemanctus serratus Cope, 1864 MNHN-RA 2094 | Duméril & Duméril (1851: 55) and Duméril (1856: 512, Pl. XXI.4, “près de la ville d’Oaxaca”, in error), as L. longipes (Wiegmann, 1834), see text |

| “Aphobérophide” | Conophis lineatus (Duméril, Bibron & D., 1854) MNHN-RA 3740 (paralectotype) | Duméril et al. (1854b: 938, Pl. 73.1–4, Tomodon lineatum), “du Mexique”; Jan & Sordelli (1866: Pl. 6.3); Bocourt (1876: 407), “recueillis à Oaxaca, par […] Ghiesbreght”; Bocourt (1886: 644, Pl. 38.5, Conophis lineatus), see text |

| “Dendrophis ?” | specific allocation and specimen (1) unknown | see text |

Auguste Ghiesbreght was gathering plants, animals, and other natural history items in Mexico for more than fifty years and “was perhaps the botanist with the greatest knowledge of the flora of northern Mesoamerica during the first half of the XIX century” (Ossenbach, 2009). One bizarre souvenir is a skull erroneously attributed to Moctezuma II (Comas 1967), the Aztec emperor M. Xocoyotzin who ruled when Hernán Cortés conquered his capital in 1519.

Surprisingly little is known about Ghiesbreght’s travelling in the country where he spent most of his life, and biographies (Rovirosa, 1889; Silvestre, 2014) basically attest a blank as to details such as his specific movements and whereabouts in the forties and early fifties of the nineteenth century. Casas-Andreu (1996) does not quote the collector at all and Flores-Villela’s et al. (2004) sketch of the herpetological exploration of Mexico, to cite an example, dedicates “Ghiesbrecht” a single mention in a short parenthesis, prompting our quest for the collector’s activities, and in the first place within Oaxaca State.

Sources and material

José Narciso Rovirosa-Andrade’s essay on Auguste Ghiesbreght is based on notes by the biographer’s friend “el Lic. Pánfilo Grajales”, a former (1882) major of San Cristóbal Las Casas [sic], and help received from the leading concurrent Mexican plant taxonomist José Ramírez. Britton (1890) formulated an English summary of Rovirosa’s (1889) publication. The bulk of information on the Belgian expedition to Mexico and Ghiesbreght exposed in Possemiers (1993b), Ceulemans (2006), Diagre (2011: 89, 95–96), and Silvestre’s (2014) exhaustive study regarding the Benelux relies upon documents in official archives, mostly covering the period from 1837 to 1840, as well as contemporary newspaper articles. Ghiesbreght’s diary, however, only exists in the present authors’ flights of fancy and the English translation of Ceulemans (2006); the original French edition merely avers the accounts of one of his companions in Mexico (“les récits de Funck”) [Nota 1].

José Rovirosa never met the profiled man and some episodes are unsubstantiated, for example Ghiesbreght’s doctor degree in Paris at young age or his military career as a surgeon in the aftermath of the ‘Night of the Opera’ on August 25, 1830, viz. the Belgian secession from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands (Silvestre, 2014). Relevant within our primary time horizon (1838–1854) are the fictive leave for a short visit to Europe in summer 1839 and the 1840 shipping of the collections erroneously dated in spring (“Marzo”). Three unspecified traverses from the Gulf to the Pacific and the ascent of various volcanoes between Jalisco and Oaxaca (“cruzó por tres veces la gran cordillera […] y ascendió á los volcanes de Colima, Jorullo y Cempoaltepec”) appear not to be quite accurate as to these summits and the mountaineer. Rather, Frederik Michael Liebmann visited the peak of Cerro Zempoaltepec and, at the same time (i.e., September 1842), our protagonist collected on Cerro Zempoala (“Sempoala”, MNHN-P 430498–99) near Huauchinango in N Puebla (Fig. 1, see The “Oaxaca” Issue). For the rest, a few of Rovirosa’s (1889) minutiae are inaccurate, for instance the date of Ghiesbreght, Linden, and Funck’s disembarkation at Veracruz allegedly at the beginning of January (“8 de Enero”) 1838 or the former’s voyage to Europe in “1857” (1856) [Nota 2].

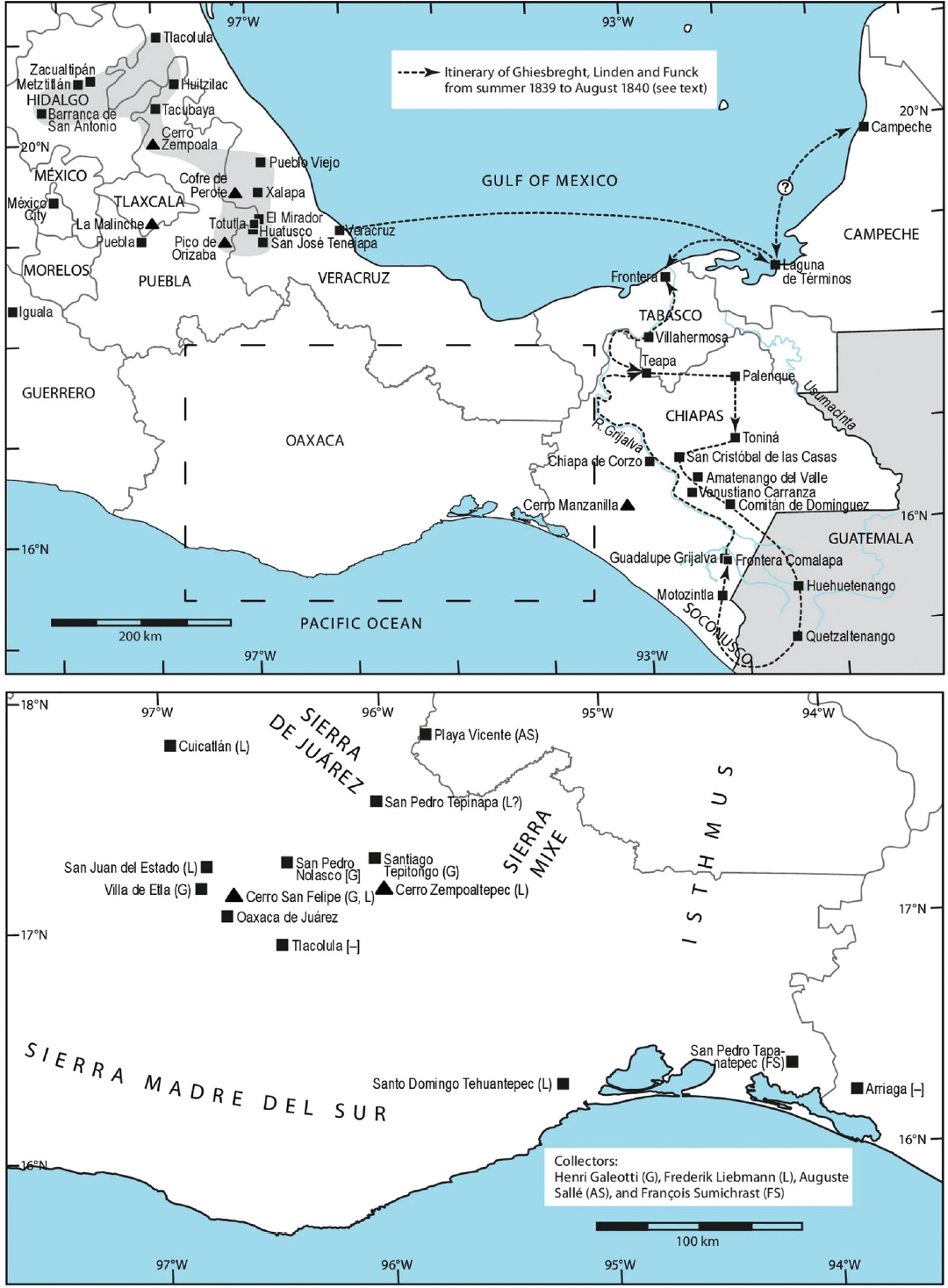

Figure 1 Localities and geographical features mentioned in the text (parts of Guerrero and area northwest to Colima not shown). Stippled area in Atlantic central Mexican highlands (Sierra Madre Oriental) shows region explored by Ghiesbreght between 1841 and September 1843. Drawing Andrea Stutz.

Admittedly, information for larger periods in Ghiesbreght’s life is virtually inexistent and most evidence has vanished in the mist of time, all but impossible to bring to light. According to his passport fetched on September 8, 1835, he was tall (170 cm) for that time, had auburn hair, and blue eyes (Silvestre, 2014: 144). The richly illustrated homage of Jean Linden by a fourth generation descendant (Ceulemans, 2006) does not show his field mate in Brazil and Mexico or later provider of living plants for his business, and an inquiry among the Council of Horticultural and Botanical Libraries neither resulted in a portrait of Ghiesbreght.

On-sight investigations did not uncover yet unknown personal data of this singular man except the death certificate in the civil registry of San Cristóbal de las Casas. The bachelor “Doctor Agustin Ghiesbreght” died on March 7, 1893 at 7 pm in his home of Santa Lucía neighbourhood by apoplexy. The body was entombed in the mausoleum of José Joaquín Peña, seemingly an intimate. That cemetery has disappeared and no new vault of this liberal lawyer, politician, and journalist could be found in today’s packed San Cristóbal de las Casas communal graveyard that opened in 1899.

Plants from “Ciudad-Real, Cacaté, les forêts de San-Bartolo et de Jitotoli” (Chiapas) and “Santiago de Tabasco [Villahermosa], la capitale, Tcapa [Teapa] et ses forêts, les Rios Tcapa, Puyapatago et Tabasco, etc.” outlined by Lasègue (1845: 213) or the fern Llavea cordifolia Lagasca, 1816 from “Chiapas pr. Amatenango” (coll. Linden) found in February (Fournier, 1872: 122) helped to establish the 1839–40 itinerary. These localities are situated in the surroundings of San Cristóbal de las Casas (“Ciudad Real”, Cacaté Ixtapa, Jitotol Municipality), Venustiano Carranza (“San Bartolo”) District, and the vicinity of Teapa including the Río Puyacatengo. Furthermore, memoirs of Linden (in Linden & Planchon 1863: LXVIII–LXIX), Ghiesbreght’s companion in Mexico from 1838 until summer 1840, unveil a few details of the Belgian exploration as, for example, a trip to Palenque two years after the description and illustration of those Mayan ruins by Frédéric de Waldeck. These recollections and James McKinney’s testimony of “three Belgians […] on a scientific expedition” in early 1840 (Stephens, 1841: 250), making us understand that they clandestinely visited archaeological sites, allow a fair approximation of the route in southern Mexico and Guatemala (see next chapter, Fig. 1) [Nota 3].

Data regarding Ghiesbreght’s life in Mexico after 1840 expounded hereafter largely relies upon his correspondence with influential members of the Paris Museum between 1842 and summer 1854, viz. Adolphe-Théodore Brongniart (“Monsieur Brogniart” or “Brogniard”, eight letters), the father of paleobotany, and the head of horticulture Joseph Decaisne (September 12, 1849). These lines composed at different places including Coscomatepec southwest of Totutla and Pueblo Viejo in Veracruz (October 1844 and May 1845, resp.) or “Tajimaroa” in Michoacán (Ciudad Hidalgo, April 1852) reveal details of the collector’s personal situation, projects, and areas or localities visited. Other annotations refer to certain shipments of plants to Brongniart. We learn, for example, that Ghiesbreght was planning an expedition to California, which he never achieved due to the lack of sponsoring or the war with the United States of America (1846–48), and that he was working on an unspecified and never published contribution to the Mexican flora. In mid-October 1849, he gave a “vivid description of his journeys through Mexico” (Ossenbach, 2007: 186, footnote 10) to another leading botanist of that time, Charles François Antoine Morren in Liège. Unfortunately, a pdf-archive of this letter got astray “through a server failure” resulting in the loss of records (C. Ossenbach in litt.), and we could not locate the original document nor a few other letters (see next chapter).

Most specimens mentioned on the following pages (coll. A. B. Ghiesbreght [ABG], “Ghiesbrecht”, “Ghisbrecht”, “Ghisbreght”, “Ghuisbreght”, or “Guisbreght”) are deposited in the Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Bruxelles (Brussels, IRSNB) and the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris (MNHN). BMNH denotes The Natural History Museum, London (former British Museum, Natural History), K is short for Kew Royal Gardens, and USNH stands for the United States National Herbarium (Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.). Ghiesbreght’s correspondence with Brongniart is filed in the botanical library of the Paris Museum (MNHN-P), and the Institut de France holds his 1849 letter to Decaisne (Ms. 2445/XX/97–98). In the case of bird taxonomy, we follow http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org (accessed December 2016) except for Pipilo cf. torquatus Du Bus, the Collared Towhee (van Rossem 1940), “an obvious hybrid” (IRSNB 3043, holotype) [Nota 4].

Information regarding vertebrate specimens housed in the IRSNB is deplorably incomplete. With respect to fishes, amphibians, reptiles or mammals, we do not know whether any material exists at all in the IRSNB, and cannot corroborate a single voucher in the Brussels collections attributed to Ghiesbreght’s Mexican field mates Linden and Funck between 1838 and 1840. We achieved to procure some general records from the bird and type registers. However, detailed requests for specific additional data did not produce any reply as to the collectors (or numbers) of holdings such as, for instance, a male paratype of Aphelocoma unicolor Du Bus, 1847 and a couple of Euphonia elegantissima (Bonaparte, 1838) from “S. Pedro” in Oaxaca (Du Bus, 1846), nor the provenance of the holotype of Arremon [Chlorospingus flavopectus] ophthalmicus Du Bus, 1847 and various syntypes of Euphonia [Chlorophonia] occipitalis Du Bus, 1847 [Nota 5].

Life in Mexico

Auguste Ghiesbreght first came into contact with the New World and its flora and fauna as a member of the Belgian expedition to Brazil between end of 1835 and beginning of December 1836. Consequently, King Leopold I commissioned the botanist and entrepreneur Jean Linden, twenty-one years old draughtsman Nicolas Funck, and Ghiesbreght to explore Central America and Colombia (e.g., Anonymous, 1837). They embarked at The Hague in October 1837 and reached Havana fifty days later. The halt on Cuba, plagued by yellow fever, prolonged and in January 1838, a royal envoy on his way to Mexico brought instructions that compelled the three voyagers to accept modification of plans and join that diplomatic mission. They may not have been very amused to learn about their new destination, due to the raising tensions between Mexico and France.

A dozen cases comprised of roughly 150 living plants collected during the three month-stay on the island were dispatched from Havana under the auspices of the Belgian Ministry of Interior in late February 1838. According to Rovirosa (1889), Ghiesbreght and his friends received orders from Prime Minister (“primer ministro plenipotenciario belga”) de Norman. In reality, Baron Félix de Norman, landlord and Major of Westmalle in Flanders with a longing for transatlantic projects, was an emissary of Leopold I in search of fortune. It was fairly frivolous to launch into that venture precisely when foreigners including diplomatic personnel were about to leave Mexico because of the looming Pastry or First Franco-Mexican War (1838–39) which had its origin in a looted French-owned confectioner shop in Mexico City.

In March 1838, the naturalists and de Norman’s entourage arrived at Veracruz (Linden & Planchon, 1863, see Notae 1–2). They marched to the capital via Xalapa where the party rested for a week and explored the outskirts. The sojourn in Mexico City demanded patience from the academic team until it received the necessary endorsement for travelling and field work issued by the Secretary of Foreign Relations and signed by Anastasio Bustamante, the President of the Republic (Rovirosa, 1889). A cargo of nine wooden boxes and crates with botanical and zoological collections left Veracruz on June 15, 1838 but was lost in the Pastry War blockade (e.g., Possemiers, 1993b).

Formally in charge of zoological aspects and in distinguished company, Ghiesbreght ascended the Pico de Orizaba (5636 m asl), the third highest North American summit, in August 1838. Another alpinist present on that occasion was the French-Belgian botanist and geologist Henri Guillaume Galeotti. A comment by the latter narrates an entire year spent with Ghiesbreght in Veracruz and what he called the Mexican plains (“une année avec M. A. Ghiesbreght dans les forêts de Xalapa et dans les plaines de Mexico”, Martens & Galeotti, 1843: 213), namely the Central Plateau from around Mexico City (“le plateau d’Anahuac”, Linden & Planchon, 1863) to the Orizaba area, the vicinity of Huatusco in the interior highlands of central Veracruz near the border with Puebla (e.g., Cofre de Perote), and all along the Gulf versant (“tout le versant oriental de la Cordillère”, l.c.), possibly as far north as Hidalgo. Galeotti’s annotation alludes to the period roughly between spring 1838 and April 1839 (Lasègue, 1845: 211, 215).

Ghiesbreght’s (1839) letter relating the time spent between the Orizaba area and their operation centre at El Mirador (see below) where he penned the lines ends with the hope that the French blockade may soon come to a term and the expectation of subsequent collecting in Oaxaca. This endeavour, however, seems never have become a reality. Linden (in Linden & Planchon, 1863) notes that they sailed from Veracruz to Campeche (“s’embarquèrent à la Vera-Cruz pour Campêche”), perhaps directly to Laguna de Términos and not the state capital. It was in summer 1839 when Linden fell severely sick with amarillic typhus, and the mission stayed put for three months (l.c.). By sea, the Belgians returned to Tabasco (Frontera) around October. They rested a moment near Villahermosa before roaming the outskirts of Teapa for a good while until the end of the year (Rovirosa, 1889), probably preparing the cargo of living plants to be picked up in July (see below) [Nota 6].

Passing through Tabasco and Chiapas, the Belgian expedition penetrated into adjacent Guatemala. In July 1840, and with rich collections aboard (fourteen containers fide Silvestre, 2014), Funck and Ghiesbreght departed by boat from Guadalupe Grijalva in Frontera Comalapa Municipality (Chiapas) via Teapa to Europe (Fig. 1). Linden set forth to Tabasco and Havana the following month and made for the United States prior to returning home. Together with his companions, he had “formed by far the largest collections we have seen from those parts of Mexico” (Hemsley 1887) [Nota 7].

Literally, Linden (in Linden & Planchon, 1863) averred that they had entered the highlands of Chiapas, made an excursion into what he described as northern Guatemala, and returned through the Soconusco along the so-called South Sea (Pacific) coast (“ils explorèrent ensuite les régions élevées […] de Chiapas, pénétrèrent dans la partie septentrionale du Guatemala […], et revinrent sur le golfe du Mexique, en appuyant vers le Soconusco et les côtes de la mer du Sud”). Given the departure from Teapa not earlier than towards the end of 1839, the unnavigable Usumacinta or mention of the Lacandon rainforest (“territoire des Indiens Locandones”), locality records of their collections or visits of Palenque and nearby Mayan ruins (“Ocosingo”, viz. Toniná, see preceding chapter), and the naturalists’ presence in the Upper Río Grijalva (Linden, l.c.: “Guadalupe de Frontera”) near the border with Guatemala before the end of July 1840 (Silvestre, 2014), there can hardly be reasonable doubt that Funck, Ghiesbreght, and Linden passed over San Cristóbal de las Casas and Comitán de Domínguez into Totonicapán-Huehuetenango (Guatemala). The territory in the latter country alluded to in Linden’s recollections is the western portion of today’s Guatemala as far east as the departments of Quiché, Sololá, and Suchitepéquez as well as Soconusco Province. Most certainly, the Belgians crossed the Sierra Madre of Chiapas above Motozintla on their way towards Frontera Comalapa (Fig. 1) [Nota 8].

Ghiesbreght spent five months (October 1840 until March 1841) in Belgium and France and left the old continent aboard the metaphorical vessel Flore, this time at his own expense. He arrived in Veracruz on May 13 after a horrific voyage (L’Observateur August 18, 1841, reproduced in Silvestre, 2014: 146–47). Ghiesbreght was supposed to gather geographic data for Philippe Vandermaelen (see Silvestre 2016: 338) and collected plants on behalf of Belgian horticulturists such as Louis Van Houtte, Henri Galeotti, and eventually Jean Linden (e.g., Morren, 1857), or natural history items in general commanded by the museums in Brussels and Paris. Private collectors including the avid Hugh Cuming acquired, for instance, snail shells today mostly housed in the BMNH (see Notae 14 and 22). However, specifics of Ghiesbreght’s life between 1841 and 1854, when he resided mainly in Mexico City (fide Rovirosa, 1889), are poorly documented.

After the westward crossing of the Atlantic, Ghiesbreght apparently pitched headquarters at Carl Christian (“Carlos”) Sartorius’s Hacienda El Mirador close to Totutla. The generous host, committed to natural history himself, collected ”at every opportunity” plants, today deposited in the USNH (Hemsley, 1887), or for example herpetological material (Flores-Villela et al., 2004). El Mirador was the place of encounter and veritable fulcrum for European travellers and naturalists, and that is where our protagonist first met Frederik Liebmann. This botanist, passionate collector of amphibians and reptiles, later director of the Copenhague Botanical Garden, and editor of the Fauna Danica had arrived in early 1841 and ascended the Pico de Orizaba at the beginning of September in company of Ghiesbreght (Liebmann, 1869). Relevant in our context is their last, and certainly prolonged, reunion at El Mirador after the Dane’s return from Oaxaca (see last chapter).

In 1842 and the following year, Ghiesbreght visited Hidalgo, the northern corner of Puebla, and central Veracruz. In September and early November 1842, he supervised the clearing of two consignments for Paris in the City of Veracruz, and spent at least a couple of days in Mexico City around mid-December. From September until the beginning of December 1843, Ghiesbreght trekked beyond the Sierra Madre del Sur (“la grande Cordellière [sic] et au-delà”, L’Observateur May 1st, 1844, see Silvestre 2014: 148, note 819), probably in Guerrero (Acapulco area), and fell sick as a consequence. This resulted in limited hunting and the suspension of shipments to Europe for the rest of 1844. Field work in Guerrero as early as in “1842” implied by, for example, a Bletia adenocarpa Reichenbach, 1856 (MNHN-P 430326, ABG 66) from the vicinity of Iguala or another orchid with a much higher field number (MNHN-P 484734, ABG 265) gathered in the same general area (“terre tempérée de la Cordillère entre Acapulco et Mexico”) is simply an impossibility (see above).

An untraceable letter to Linden in Venezuela, supposedly written in 1844, relays the grief of Carmencita desperately longing for Linden’s return (Ceulemans, 2006). However, we do not know how Ghiesbreght learnt about the young Creole beauty’s solitude and whether his words testify a recent visit to Teapa and reunion with their 1839 host, namely the girl’s seemingly wealthy father. Another equally vague pointer is a vicious assault by brigands near Puebla in “1846” (fide Rovirosa, 1889).

Specimens (ABG) from Michoacán (e.g., MNHN-P 623856, Apatzingán) were collected from 1845 onwards. Orchids from unspecified places in this state (1849–50) or the central Mexican Pacific versant (1853) including northern Guerrero (Du Buysson, 1878: 203, 409, 431) date from as late as into the next decade (e.g., Morren, 1857). Ghiesbreght’s presence in Michoacán over a certain period (1852–53) is corroborated by letters to Brongniart. A strong hint that the collector had ties with compatriots operating business there are the late summer 1849 lines to Decaisne penned in the house of “J. Keymolen”, a relative of the contentious Belgian consul (Louis K.) at Mexico City. Two plants from Colima (MNHN-P 624895–96) farther northwest along the Pacific versant were probably gathered during an expedition in the mid-forties [Nota 9].

It seems that Ghiesbreght had suspended the search for orchids, bromeliads, etc. towards 1850 because of private motives and reasons beyond his control such as, after war with the northern neighbour (1846–48), the raging cholera epidemic of 1848–1850. In the long term, however, this was contrary to his gusto and neither risk nor danger could deter him from answering the call of passion for nature as he put it in letters to Brongniart. After an interruption of several years, the collector re-established relations with the MNHN in summer 1852.

In 1855, Ghiesbreght took up residence in Teapa and returned to Europe the following year, for the first time since March 1841 (see Note 7 and Silvestre 2014: 149, note 822). The passengers’ list of the Porta-Coeli reproduced in a Mexican newspaper (Anonymous 1856) affirms the arrival of “Augusto Ghiesbreght” in Veracruz from Le Havre (departure August 30).

After a longer stay at Hacienda La Bellota of Manuel Jamet on the Tabasco coast in 1862, Ghiesbreght made for a journey to San Cristóbal de las Casas that same summer (Rovirosa, 1889). From November 1862 until his death, “D.[on] Agustín, el Naturalista” as he was known among locals (Rovirosa 1893: 72), lived in that South Mexican highland city and then Chiapanecan capital. There, he helped the community in matters such as the determination of the town’s elevation (Anonymous, 1886) and did not tire of providing medical service for the poor. An obituary of Ghiesbreght appeared, for example, in a Mexico City based English newspaper (Anonymous, 1893a).

Amphibians and reptiles from “Oaxaca”

Two lots composed of a total of twenty-seven specimens purportedly from Oaxaca were purchased from Auguste Ghiesbreght and incorporated into the collection of the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (MNHN) at the very beginning of August 1842 and in October 1845, respectively. They belong to twelve species, viz. two amphibian, three lizard, and seven snake taxa. Except in the case of the untraceable “Tropidonotus saurita” series, ophidians are represented by single specimens, and two among them (“Lycodon ?” and “Dendrophis ?”) cannot be located for the time being (Table 1). They may be destroyed or are possibly lost (see last paragraph of chapter) [Nota 10].

Given the systematic concept, generic allocations, and higher rank terminology used by the then head of the herpetology and ichthyology department (e.g., Duméril & Bibron, 1844; Duméril et al., 1854b: p. I, “Serpents opisthoglyphes ou Aphobérophides”), the latter family name denotes the back-fanged Conophis lineatus (Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1854), and we tentatively identify “Psammophis ?” with Coluber constrictor oaxaca (Jan, 1863). In the case of the systematically problematical Oaxacan Milk Snake (Lampropeltis Fitzinger, 1843), we follow recent local contributions (e.g., Mata-Silva et al., 2015; Schätti & Stutz, 2016) and refer the species in question to L. cf. polyzona Cope, 1860 [Nota 11].

The catalogue of acquisitions gives no individual locality data for Ghiesbreght’s 1842 and 1845 lots, although the corytophanid lizard and natricid taxon were later published with more precise indications. The origin of Coryphodon oaxaca Jan is contradictory (Table 1) and Tomodon lineatus Duméril, Bibron & Duméril was introduced without a hint to Oaxaca or the collectors (see Nota 11).

As is evident from the illustration in Duméril (1856: Pl. XXI.4), a Casque-headed Basilisk (“Laemanctus longipes”) from the vicinity of Oaxaca de Juárez (“près de la ville d’Oaxaca”, l.c.) belongs to L. serratus Cope, 1864. This area above 1500 m asl on the Central Plateau is completely isolated from all Mexican populations at “low and moderate elevations” in Veracruz, Chiapas, and the Yucatán Peninsula (McCranie & Köhler, 2004b). The species has never been found again in Oaxaca and the origin of MNHN-RA 2094 is indeed incorrect [Nota 12].

The wording in Duméril et al. (1854a: “recueilli à Oaxaca”) regarding the provenance of at least one (i.e., that used for preparation of the skull) out of six “Tropidonotus saurita” refers to a place rather than a region, viz. the City of Oaxaca de Juárez and not the homonymic state. The proper identification of the unlocated Garter Snake series (Thamnophis Fitzinger, 1843) and individual allocations remain open to debate.

We did not unearth herpetological specimens (ABG) other than those cited in this text (1842–1854) and shipments received after 1854 probably entirely consisted of dry vouchers, basically plants and snail shells (see Discussion). Although the holotype of Coryphodon oaxaca Jan (MNHN-RA 7378) cannot be precisely assigned to one of the originally undetermined taxa, there can be no doubt that this and another type specimen (MNHN-RA 3740, Conophis lineatus) must have been received between 1842 and 1845 because both snakes present in Ghiesbreght’s next (1854) delivery (Tantilla deppii, Thamnophis melanogaster, see Nota 10) are not considered in the ‘Erpétologie générale’ issues (vol. 7) published that same year.

Pituophis mexicanus Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1854 was established upon an unknown number of individuals with unspecified origins and different provenance (“envoyée du Mexique par plusieurs voyageurs”) including “Ghuisbreght” [sic], the only specified collector. Despite the lack of indication, we think that this might be MNHN-RA 3188, a fine specimen of nearly two metres total length. Morphologically, that syntype is most similar to P. catenifer (Blainville, 1935) differs from P. deppei (Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1854) and clearly so vis-à-vis the southern highland P. lineaticollis (Cope, 1861) from SW Michoacán into SW Guatemala [Nota 13].

As in the case of Coryphodon oaxaca Jan (see second paragraph of chapter), we cannot positively associate Pituophis mexicanus Duméril, Bibron & Duméril with any ledger record, and in particular material provided by Ghiesbreght (see Table 1 and Nota 10). Admittedly, it seems hard to imagine that this taxon had originally been classified as “Lycodon ?” or “Dendrophis ?”, viz. the supposedly missing “Oaxaca” taxa. However, it cannot be excluded that this is exactly what happened. A plausible explanation would be that these generic names were those attributed to the specimens by Ghiesbreght, and conveniently adopted by Gabriel Bibron when he registered the 1842 and 1845 lots (Table 1). Even under that assumption, our identification of the Racer (Coryphodon oaxaca Jan) with “Psammophis ?” makes sense. Another possibility that cannot be ruled out based on the absence of data for the syntype of P. mexicanus among Ghiesbreght snakes consists in a confusion of the collector by Duméril et al. (1854a).

Discussion

Our attempt to retrieve information on botanical and zoological items discovered by Auguste Ghiesbreght in Oaxaca State involved the examination of a large number of natural history literature and specimens. However, expectations to unearth relevant details and get a clear picture of the areas visited by this ardent and vigorous naturalist dwindled in the course of our investigation and made way to meagre results in terms of positive evidence, but not necessarily so in circumstantial findings.

Mexican natural history material obtained by Ghiesbreght prior to 1841 (e.g., Nyst, 1841) is deposited in Belgium including the IRSNB (see Sources and Material). Specimens in other European collections, mostly plants, were registered starting in 1842. That year, various departments of the Paris Museum (MNHN), for example, bought lots from Ghiesbreght (e.g., Duméril & Bibron, 1844: p. X, “Ghuisbreght”; Papavero, 1971; McVaugh, 1972; Papavero & Ibáñez-Bernal, 2001, see Notae 4 and 14). At the same time, the French banker, businessman, and passionate botanist Benjamin Delessert acquired Mexican plants with identical provenance (Lasègue, 1845: 211). The latter reference, one of the few to quote collecting sites other than Mexico (or “Mexique”) or often incorrect origins such as “Tabasco” (see below), specifies localities (coll. “Linden”) in the latter state and Chiapas (“Chiapan”), as does Rovirosa (1889) for the years after 1854.

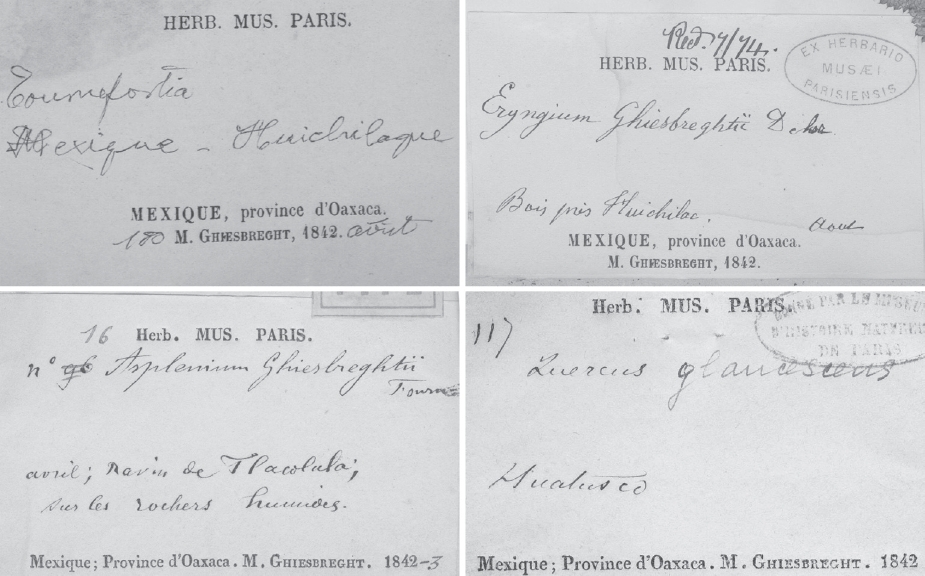

Digitalised specimens (ABG) with useful locality data basically housed in the MNHN-P (see Nota 4) demarcate the region investigated by Ghiesbreght between January and early September 1842 and the same period in the following year. All sighted items bearing a specific origin and uncontestably gathered in 1842–43 (incl., e.g., BMNH 1045304 and K 529746 received in exchange) come from Hidalgo, far northern Puebla, and central inland Veracruz. These series are comprised of Ghiesbreght’s handwritten field labels up to no 124 (presenting some minor gaps and ABG 85–105 missing) as well as 180 (e.g., MNHN-P 3897154, Figs 1–2) [Nota 14].

Figure 2 “Oaxaca” labels of a Tournefortia sp. (MNHN-P 3897154, upper left) and Eryngium ghiesbreghtii Decaisne, 1873 (K 529746, upper right) from Huitzilac (“Huichilaque”) in northernmost Puebla as well as Asplenium ghiesbreghtii Fournier, 1872 (MNHN-P 219954, “type”, lower left) and Quercus glaucescens Kunth, 1817 (MNHN-P 754021, isotype, lower right) from Tlacolula and Huatusco, respectively, in central Veracruz (Fig. 1).

The only specific faunistic passage in Ghiesbreght’s correspondence is the description of the content of a box with sixty-two terrestrial snails (24 spp.) on the packing list of the late 1841 shipment. Published Mexican records (ABG) appear to be absent for large insect orders (Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera) or Mantodea, Odonata, and Orthoptera, as well as Arachnida and other arthropods or further invertebrate phylae other than gastropods and diptera enumerated in Nota 14. With regard to lower vertebrates or mammals, we did not hit upon any detailed Mexican locality at all (see Sources and Material incl. Nota 5 regarding IRSNB, preceding chapter, and Nota 20).

Thirteen supposedly new species of birds from northern Mesoamerica described by Du Bus (1845–46, 1847a–b), four valid taxa assigned to Bonaparte (1850) upon an unfinished manuscript by the former, a junior synonym of the White-crowned Sparrow Zonotrichia leucophrys (Spizella maxima Bonaparte, 1853), and Cyanocitta [Cyanocorax] yucantanica Dubois, 1875 are partly devoid of collecting data as noted by van Rossem (1940: “no locality […] nor […] original source either in the register or on the stand”) in context with the male holotype of Pipilo torquatus (“No. 7391”, viz. IRSNB 3043, see Nota 5).

The provenance (ABG) is confirmed for ten birds with type status from Mexico including the vicinity of the “Hacienda de Mirador” or “Xalapa” in Veracruz, “Tabasco”, and “Yucatan” (IRSNB 3014, 3016, 3020–21, 3031, 3034, 3051, 3091–93) and six additional items (3015, 4724, 5258, 7417, 7581, 7581β) encompassing a supposed “cotype” of Buteo ghiesbreghti Du Bus, 1845. Another fourteen specimens comprising at least eleven holotypes and a paratype apparently have no data as to their collectors and it is questionable how many may have been obtained by Ghiesbreght (Appendix) [Nota 15].

Cyanocorax unicolor and Sylvia taeniata Du Bus were described from “Mexique”, and the former was subsequently illustrated and reported from various places including “Tabasco” (Du Bus 1848: Pl. 17, IRSNB 3034, “Voyage Ghiesbreght” fide register, see Appendix). Nevertheless, van Rossem (1942) indicates the origin of both the Unicoloured Jay and Olive Warbler to be “Tabasco”, considers their respective “type” to have been “without doubt collected by Ghiesbreght in the same locality” of Chiapas (“it is certain that Chiapas, not Tabasco, is the type region of both”; see Hellmayr 1934: 58, footnote 2, “The locality «Tabasco» [for C. unicolor] can hardly be correct”), and he is mistaken when stating that the former was encountered “probably in the spring of 1838 or 1839”. The holotype (IRSNB 3034) of this cloud forest species was likely shot during the traverse of Chiapas in 1840 (see Life in Mexico, Nota 14 regarding Teapa area, and below as to paratypes from Oaxaca).

Nominal bird species described by Du Bus (1847a–b, 1855) from unspecified places in Mexico (except Playa Vicente) or Guatemala and definitely not collected by Ghiesbreght include Carduelis notata (Spinus notatus, IRSNB 3044, holotype, “don. Carron de Villardt 17. IV. 1855”), Cyanoloxia concreta (C. cyanoides concreta, see Nota 16), Ischnosceles niger (Geranospiza caerulescens nigra, IRSNB 3032, holotype, “Achat Verheyen 29. XI. 1847”), Monasa inornata (Malacoptila panamensis inornata, IRSNB 3047–48, syntypes, “Achat C. Dubois 27. VIII. 1847”), or Prionites carinatus (Ramphastos sulfuratus Lesson, 1830, IRSNB 3049, holotype, “Achat Dubois 27. VIII. 1847”) [Nota 16].

Two “young of the year” (van Rossem, 1942) paratypes of Aphelocoma unicolor (♂♀ fide Du Bus, 1848) from Oaxaca have identical origins as reported for a pair of Euphonia elegantissima (“S. Pedro”, Du Bus, 1846) and a male syntype (IRSNB 3017) of Trogon collaris shot at “Tepitongo” in September 1843 (Du Bus, 1845: T. xalapensis). Du Bus (1848: footnote, “indications […] données par la personne même qui a tué ces oiseaux”) does not unveil the identity of the person who killed the two A. unicolor, which appears to be Henri Galeotti who sold at least the female paratype from Tepitongo (IRSNB 3035, “Achat Galeotti”, see Sources and Material incl. Nota 5 regarding lack of data for three “S. Pedro” specimens incl. E. elegantissima). The collector of the trogon is unknown (“inconnu” fide register) but this paratype was likely obtained from the same provider. By all means, Galeotti shot a Middle American Saltator, Saltator coerulescens grandis (Deppe, 1830), at Tepitongo in “Sept.” (Salvin, 1882: 200, year not specified) as well as a Black-throated Gray-Warbler, Setophaga nigrescens (Townsend, 1837), a male Eastern Warbling-Vireo, Vireo gilvus (Vieillot, 1807), or a female Bush Tanager, Chlorospingus flavopectus ophthalmicus (Du Bus, 1847), at “San Pedro” (Salvin, 1882: 90) or “S. Pedro” (l.c.: 112, 196) in October (S. nigrescens, Ch. f. ophthalmicus) and December (V. gilvus) 1844 [Nota 17].

Our brief analysis of the distribution pattern of Ghiesbreght’s MNHN-RA amphibians and reptiles from “Oaxaca” (Table 1) does not take into account the unlocated Thamnophis sp., or different spp., nor MNHN-RA 0419 (Lampropeltis cf. polyzona). This Milk Snake belongs to a genus with disputed species concepts and would hardly contribute useful information.

The Tree Frog Smilisca baudinii inhabits Mesoamerican tropical lowlands southeast into Costa Rica whereas the False Brook Salamander Pseudoeurycea gadovii (det. David B. Wake) is confined to alpine habitats at elevations higher than 2200 m above sea level in Puebla, Tlaxcala, and limitrophe Veracruz, viz. the Pico de Orizaba (type locality), La Malinche, and Cofre de Perote Ranges, respectively (Solano-Zavaleta et al., 2009).

The endemic Mesquite Lizard Sceloporus grammicus extends over large parts of Mexico and is found, for instance, throughout the Oaxacan highlands. The Mesoamerican Rose-bellied Lizard S. variabilis occurs along the Gulf versant and in SE Oaxaca (Mather & Sites, 1985; Mata-Silva et al., 2015: Table 4). The Casque-headed Basilisk Laemanctus serratus is absent from the whole state (see preceding chapter).

The Racer Coluber constrictor oaxaca is recorded from northern Mexico and the Gulf region into Guatemala (Wilson, 1978: Map). The few known collecting sites situated closest to Oaxacan territory are in the vicinity of Tierra Blanca and at the western limit of the Central Isthmus in Veracruz (Pérez-Higareda & Smith, 1991) near the state border (Atlantic lowlands along Sierra de Juárez and S. Mixe), and Ocuilapa in W Chiapas (Smith, 1971). The presence of this taxon in Oaxaca is “inferred” (Wilson 1978) from or “implied” (Smith & Taylor, 1945) by the scientific name and far from confirmed (“perhaps «Oaxaca»”, l.c.). Mata-Silva et al. (2015: Table 4) correctly question (“?”) the occurrence of C. constrictor oaxaca in this state [Nota 18].

Within Mexico, the Mesoamerican xenodontid Conophis lineatus is reported from Jalisco, Querétaro, and Veracruz to the Yucatán Peninsula (see Wallach et al., 2014). The species occurs in the Central Isthmus at Matías Romero (Conant, 1965) and the Tehuantepec Plain (Mata-Silva et al. 2015: Table 4). Bocourt’s (1876, 1886) mention from Oaxaca de Juárez based on Ghiesbreght’s paralectotype is unsubstantiated (MNHN-RA 3740, see Table 1 and Nota 11). Highland records of “Conophis lineatus (Kennicott in Baird, 1859)” from the “Sierra Madre de Oaxaca”, the “Mixteca alta”, and “Valles centrales” (Casas-Andreu et al., 2004) belong to Conopsis lineata (Kennicott).

The Snaileater Sibon dimidiatus (Günther, 1872) from Veracruz to Central America occurs along the Oaxacan Gulf versant (Kofron, 1990). It appears that nobody has ever examined MNHN-RA 7279 since Mocquard (1908) who refers Ghiesbreght’s specimen to Petalognathus nebulatus (Linnaeus, 1758) and mentions various (“plusieurs”) specimens lacking names of collectors and with identical origin (“Mexique”) as reported by Duméril et al. (1854a).

Based on the above, we conclude that two species among Ghiesbreght’s “Oaxaca” amphibians (Pseudoeurycea gadovii) and reptiles (Laemanctus serratus) are absent from this state. The Racer (Coluber constrictor oaxaca) at best enters peripheral Atlantic areas and Conophis lineatus is only documented for the Isthmus (see above and penultimate paragraph of chapter), resulting in strong reservations as to the genuine origin of specimens with the provenance “Oaxaca” (Table 1). The salamander was most likely collected between Tlaxcala and the Puebla–Veracruz border region east of the Central Plateau. As a matter of fact, both amphibian species and all systematically verified “Oaxaca” lizards and snakes (ABG) are recorded from within less than fifty kilometres between Huatusco and Xalapa (i.e., Hacienda El Mirador) encompassing altitudes from below 1000 m around the former town to over 4000 m above sea level (Fig. 1). A plethora of plants from Ghiesbreght with detailed locality data and gathered in the same period as his herpetological specimens (1841/42–1854) in fact originates from that comparatively small area (see Nota 4, Life in Mexico, and below). Higher elevations close to the Puebla border west of the capital Xalapa are also inhabited by the pinesnake Pituophis deppei, a species that potentially might have made part of the 1842 or 1845 shipment (see preceding chapter) [Nota 19].

No first-hand information is available regarding herpetological material (ABG) in the IRSNB (see Sources and Material). Werner’s (1909) Crocodylus rhombifer (Cuvier, 1807) from “Mexiko” is without further published data. The malacophagous snake Leptognathus maxillaris Werner, 1909 (“No. 120”) was described on the basis of a single specimen from “Tabasco, Mexico”, viz. IRSNB 2026 received from Linden (“17. XI. 1857”, Lang 1990). Laurent (1949: Figs 20–22) examined and illustrated this female (“I. G. no 1939, Reg. no 3042”, see Nota 5). Dipsas maxillaris (Werner) is only known from the holotype, the origin probably in error (suspected to be in South America), and the taxon possibly a synonym of D. elegans (Boulenger, 1896) whose type locality (“Tehuantepec”, leg. Boucard 1871) is equally incorrect (Kofron, 1982: 46; Cadle, 2005: 88 incl. footnote; Schätti & Stutz, 2016: nota 2). We suppose that the name-bearer of L. maxillaris Werner was collected during Linden’s botanical explorations in Colombia and parts of Venezuela.

THE “OAXACA” ISSUE

One of our initial hypothesis conjectured a possible northwestward march of the Belgian expedition along the Chiapanecan coast in summer 1840 on their way back to the Gulf. However, the assumption must be refuted that the explorers might have entered extreme SE Oaxaca near San Pedro Tapanatepec, or having traversed the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Nothing indicates a fastidious detour over Arriaga close to the recent Chiapas–Oaxaca border and via Chiapa de Corzo (Tuxtla Gutiérrez) far downstream of Guadalupe Grijalva, the point of embarkment. That potential route would neither have made sense nor be in line with the time schedule of the party (see Life in Mexico). Moreover, our investigations did not generate evidence for Ghiesbreght’s supposed north-south passage of Oaxaca (Rovirosa, 1889). At any rate, there is no hint whatsoever as to collecting in the Tehuantepec area (Isthmus) or the contiguous Pacific coast of Oaxaca [Nota 20].

Apart from his expressed hope for collecting in “Oaxaca”, once the French blockade were over, at the end of the 1830’s (see Life in Mexico), we came across a single mention of this state by Ghiesbreght himself in his reply to a letter from Brongniart. These lines composed in the City of “Vera Cruz” in mid-September 1842 specify the contents of various containers sent to Paris and refer to the difference of the flowers among morphologically otherwise highly similar species of “macrobulbum orchidées” (possibly incl. Epidendron [Cyrtopodium] macrobulbon La Llave & Lexarza, 1825) in a former “Oaxaca” cargo (“[…] envoyé […] dans mon second envoi de Oaxaca”). Taking into account all available evidence and the context of the letter, there can hardly exist doubts about a lapsus calami, namely that Ghiesbreght rather meant the delivery from the Orizaba region encompassing the northwestern foothill areas (e.g., vic. Coscomatepec) probably despatched in late 1841.

The complete lack of information on Ghiesbreght’s whereabouts in Oaxaca and not a single reliable specific locality record from there inspire certain unease. Qualms as to the true origin are nourished by McVaugh’s (1972) thought-provoking discovery in the Paris herbarium. This author found plenty of “printed labels, with […] a line at bottom «Mexique-Province d’Oaxaca M. Ghiesbreght. 1842»” on sheets with plants from outside this state (see text, Fig. 2). Specimens “commonly bear additional handwritten labels, often with precise information as to locality of collection”, for example in the case of a Crownbeard and another Sunflower species (Asteraceae) with “Oaxaca” tags but actually from Morelos. Similarly, Renner & Hausner (2005) report the lectotype of the shrub Citriosma riparia Tulasne, 1855 (Monimiaceae), a junior synonym of Siparuna thecaphora (Poeppig & Endlicher, 1838), from “Veracruz [«Prov. Oaxaca»]: Huatusco, 1843 (female), coll. Ghiesbrecht” [sic] [Nota 21].

The borage Ehretia tinifolia Linnaeus, 1759 from Cuicatlán (“Quicatlan”, MNHN-P 3514373, ABG 58, coll. “1842”) and the epiphytic orchid Rhynchostele aptera (La Llave & Lexarza) Soto Arenas & Salazar, 1993 from San Juan del Estado (MNHN-P 449989, no 4, “1842-3”) are indeed from Oaxaca. That year, however, Ghiesbreght travelled through the Atlantic interior highlands between Hidalgo and central Veracruz. At the same time, his friend Liebmann explored the Southern Plateau between Tehuacán in SE Puebla and Oaxaca de Juárez (until end of May) including “Cuicatlan” and the “Cuesta de San Juan del Estado (9400 pieds)”, viz. the northern precipice of the San Felipe Range (Cerro Peña de S. F.) close to 3000 m above sea level. Subsequently, this naturalist climbed the Zempoaltepec (“mont Sempoaltepec”), descended to the Pacific coast in October, visited the Tehuantepec area, and returned over the Oaxacan capital to El Mirador in January 1843 (Liebmann, 1869). There, the latter most probably ceded duplicates of his plants to Ghiesbreght whose presence at the hacienda is corroborated by, for instance, a Tillandsia pruinosa Swartz, 1797 (MNHN-P 1641216, see Life in Mexico).

The terrestrial gastropod Ampullaria eumicra Fischer & Crosse, 1890 (lectotype MNHN-IM 2000.23082, ABG), presumably a junior synonym of Pomacea f. flagellata (Say, 1827), was described from Oaxaca (“in provinciâ Oajaca dictâ”) and the type locality carelessly positioned near the Pacific coast (l.c.: 244, “Mexique, dans l’Etat d’Oajaca, près du Pacifique”). Apart from the immediately preceding taxon (A. innexa Fischer & Crosse, 1890) with identical origin and synonymy (“Oajaca”, P. f. flagellata), not a single Oaxacan snail shell was received from Ghiesbreght according to Fischer & Crosse’s (1888, 1890, 1893) indications. The introduction to the first volume of the land and sweet water molluscs (l.c. 1870: 3, 7 [table]) states that Ghiesbreght explored in particular “Oajaca” and Chiapas, but all specimens associated with him are exclusively reported from the latter state or, in a few instances, the southern part of Mexico (“Habitat in parte meridionali reipublicæ Mexicanæ”) and “Tabasco” (p. 363). Material from Oaxaca indeed comes from other collectors including Boucard and Sallé (see Nota 15) [Nota 22].

To summarise, our search for Auguste Ghiesbreght’s natural history items from “Oaxaca” produced no trustworthy locality record situated in that state. With respect to amphibians and reptiles, the salamander Pseudoeurycea gadovii is a central Mexican high altitude endemic with a restricted distribution range, the reputed presence of the basilisk Laemanctus serratus in the vicinity of the capital Oaxaca de Juárez is conclusively in error, and at least two out of eight (without Lampropeltis cf. polyzona) systematically identified species purportedly obtained in Oaxaca have never been recorded from there. Scientific specimens with that provenance may in reality hail from any region visited by the collector during the 1840’s, and in particular the Gulf draining inland versants from Hidalgo to the Orizaba Range. We strongly suppose that most, if not all, MNHN-RA herpetological material from “Oaxaca” (ABG) was in fact obtained between Huatusco, Xalapa, and the Cofre de Perote in the interior highland area of central Veracruz along the border with Puebla.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)