Introduction

A relationship between the potential role of within-species geographic variation of phenotypic traits is a crucial issue in evolutionary biology because such variation can lead to local adaptation to ecological gradients, likely as a by-product of morphological adaptation (Boughman, 2002; Fisher-Reid & Wiens, 2015). Populations are subject to environmental gradients, thus individuals are likely to be restricted to local conditions, and subsequently promote a phenotypic trait variation between populations (Ribeiro et al., 2014). On a general level, there is a broad consensus that sexual dimorphism primarily reflects the adaptation of males and females to their disparate reproductive roles; however, the sexual dimorphism in traits not closely related to reproductive function, such as feeding and locomotory structures, are generally associated with ecological differences between sexes; this idea has led to the hypothesis that sexual dimorphism could reflect an adaptation of the two sexes to different ecological niches rather than to different reproductive roles (Fairbairn, 2007).

In hummingbirds (Trochilidae), morphological traits play an important role in our understanding of origin, evolution, and species or populations delimitation (Bleiweiss, 1998; Roy et al., 1998; Graham et al., 2012) because these traits are related to flight ability, physiology and feeding adaptations, behavior and sexual dimorphism (Bleiweiss, 1998; Roy et al., 1998; Temeles et al., 2010; Graham et al., 2012; Berns & Adams, 2013). Particularly, sexual dimorphism may be expressed as physical traits (e.g. body and shape size, wing and bill morphology, plumage and ornamentation), depending on the gender roles and ecological functions that males and females perform, such as feeding, mating, parental care, and other life-history characteristics (Fairbairn, 2007; Berns & Adams, 2010, 2013). For instance, because females perform all parental care and mate choice, they select mates with phenotypes that reflect fitness in order to ensure a successful reproduction and low offspring mortality (Berns, 2013). However, males may also be under selection pressure, first, due to what the mating-competition hypothesis states that males compete over females and her size is often advantageous; second, because females may prefer males with acrobatic displays and it is known that small size increases the maneuverability (display-agility hypothesis); and third, due to the resource-division hypothesis that states that increasing sexual dimorphism avoids exploiting the same resources when both sexes forage together and use the same territory (Szekely et al., 2007).

Ecological and behavioral traits are likely the common causes for the pattern of sexual size dimorphism. When morphology and behavior constrain each species to a limited range of resource densities, natural selection tends to diversify body size among species. If mating is promiscuous or polygynous, sexual selection favors large males when resources are sufficient (Colwell, 2000); thus, males tend to be generally larger than females having a bright plumage or ornamentations that increase the probability to be selected by females (Berns & Adams, 2013). But if male reproductive behavior is energetically costly, smaller males may have an advantage when resources are limiting, producing a pattern of allometry for sexual size dimorphism that conforms to Rensch´s rule (Colwell, 2000).

Xantus’ hummingbird Hylocharis xantusii (Lawrence, 1860) shows a strong sexual dimorphism in the color pattern; this hummingbird has a white post-ocular stripe contrasting strongly with a broad, blackish auricular mask, cinnamon belly, and males have an orange bill and remarkably colorful plumage around the throat to the head (Howell & Howell, 2000). Body measurements differences by sexes have not been well determined.

Xantus’ hummingbird distribution ranges across the Baja California Peninsula (BCP), and it is an endemic species to the central and southern region of the BCP (Howell & Howell, 2000). This hummingbird uses a wide array of habitats, from costal vegetation at sea level, mesic vegetation of oases, tropical deciduous forest (300–800 m), and oak-pine forests (above 1,400 m only in the Sierra de La Laguna; Rodríguez-Estrella, 1997; Rodríguez-Estrella et al., 2005;). In the arid desert temperatures can rise up to 50 °C, while in the temperate habitat of Sierra de la Laguna and oases temperatures do not exceed ~30 °C (Arriaga & Rodríguez-Estrella, 1997; Arriaga et al., 1997; Rodríguez-Estrella et al., 1997).

Hylocharis xantusii is a neotropical bird that has adapted to neartic xeric conditions and has a discontinuous distribution into the BCP divided in three genetic populations: southern, central and northern populations (González-Rubio et al., 2016). Little is known about their ecology, but it has been found that has a mutually dependent relationship with other endemic species, such as the endemic madrone Arbutus peninsularis in the Sierra de La Laguna in the Cape Region (Arriaga et al., 1990), and forages on a variety of shrubs and herbaceous plant species. H. xantusii is co-distributed only with Costa’s hummingbird Calypte costae; however, H. xantusii has been observed is restricted to the mesic conditions of oases and edge arroyos.

Xantus’ hummingbird provides an interesting opportunity to examine whether the environmental differences over the particular topography of BCP may have determined patterns of intraspecific geographical variation in morphological traits. Our hypothesis is that due to its discontinuous distribution, its tight relationships with isolated oasis´ environment, and its population genetic differentiation we could find differences in morphological traits among populations and that sex differences will be found too. In this study, we aimed first to quantify morphological variation between males and females to determine sexual dimorphism traits, and second to test whether there are differences in morphological traits between populations.

Materials and methods

Fieldwork was conducted in 10 locations throughout the Hylocharis xantusii distribution at the BCP (Fig. 1). During spring and autumn in 2012-2014, every location was sampled for three days and only adults were captured with mist nets (4-6 nets per site) and determining sexing by bill coloration and plumage. Morphological traits were measured to determine differences between males and females and also to test for differences among locations, oases and genetic populations as determined in González-Rubio et al. (2016). Six morphological traits were taken (Fig. 2) using digital vernier to an accuracy of 0.1 mm: total length (mm), wing chord (mm), tail length (mm) and bill size (bill to culmen, bill to nostril, and bill width; mm). Hummingbirds were marked to avoid recaptures and safely released once data was acquired and none was injured.

Figure 1 Studied locations for Hylocharis xantusii endemic of the Baja California Peninsula. Sampling sites names are shown in Table 1.

A general linear model (GLM; McCullagh & Nelder, 1983) was used to model morphological trait differences between sexes and among localities using environmental variables as predictors. Morphological traits were total length, tail length, wing chord and bill size. Predictors were location latitude, longitude, altitude, genetic population and oasis. Each variable was tested in turn for significance, and only those variables significant at the 0.05 level were included in the model. Explanatory variables and their interactions were fitted to the observed data following a stepwise forward procedure beginning with the random terms and testing each explanatory variable and its interactions separately. To control for the eVects of body size on morphological traits, we used a GLM to generate adjusted marginal trait means with “region” (oasis) as the Wxed factor, PC 1 (a “size” factor) as covariate to control for shape variation due to body size (i.e. multivariate allometry) (Langerhans et al., 2003), and a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed with Minitab 15 statistical software (Minitab, Inc. Pennsylvania, US).

The mean and standard error (SE) of the six traits were estimated by location, pooling all males and females of that location. Raw data met the assumptions of homogeneity of variances (Levene test) and normality (the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Trait differences between males and females were pair-compared using Student’s t test. Two-way ANOVA was used to identify morphological differences attributed to different populations defined by morphological traits, the sex, and the intersection population/sex. A post hoc comparison of means was tested using Fisher’s LSD when a significant effect was found. The Bonferroni correction was applied to multiple comparisons. These statistical analyses were performed with Statistical 7 software (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK).

Results

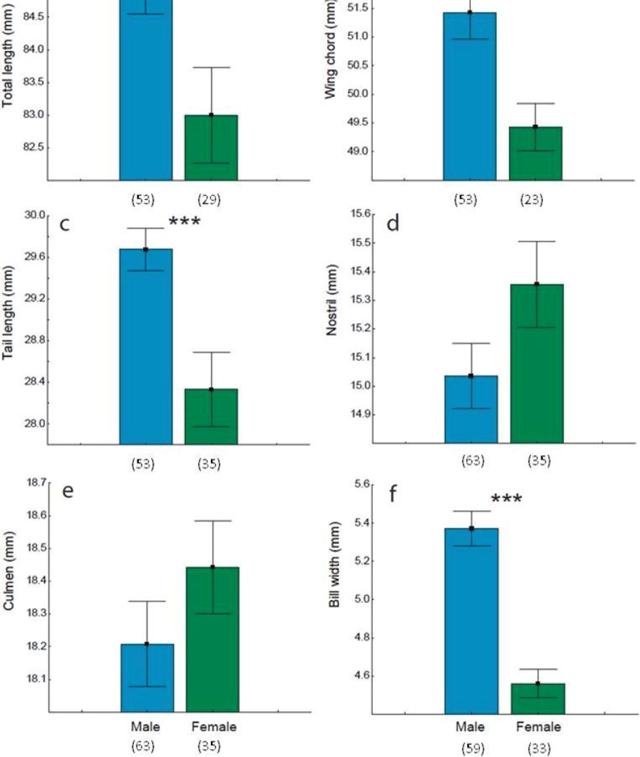

We trapped 98 adults, 63 males and 35 females (Table 1). A morphological dimorphism was found in four of the six traits analyzed in this study (Fig. 3). Xantus’ hummingbird males were bigger in size (total length, Fig. 3a) with larger wings (wing chord and tail length, Fig. 3b-c) and wider bills (bill width, Fig. 3f). Although in average the bills to nostril and culmen of female hummingbirds were larger than males, these traits were not significant (t test, p > 0.05, Fig. 3d-e).

Table 1 Sampling sites used in this work for comparing morphometry of endemic Xantus’ hummingbird (Hylocharis xantusii) populations in Baja California peninsula. Genetic populations* and sample sizes for males (M) and females (F) are indicated for each location. Numbers of sampling sites correspond to numbers in Fig. 1.

| Locations | Genetic population* | M | F | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Santa Gertrudis | North | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| 2 | Carambuche | Central | 13 | 1 | 14 |

| 3 | San Isidro | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| 4 | San José | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| 5 | San Miguel | 5 | 3 | 8 | |

| 6 | San Javier | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| 7 | La Soledad | South | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| 8 | San Blas | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| 9 | Santiago | 14 | 9 | 23 | |

| 10 | Sierra La Laguna | 7 | 3 | 10 | |

| Total | 63 | 35 | 98 |

* From González-Rubio et al., 2016.

Figure 3 Morphological traits (mean ± standard error) between male and female of Hylocharis xantusii. Individuals analyzed are indicated in parenthesis. Significant differences in “t” test, ** = (p < 0.01), *** = (p < 0.001).

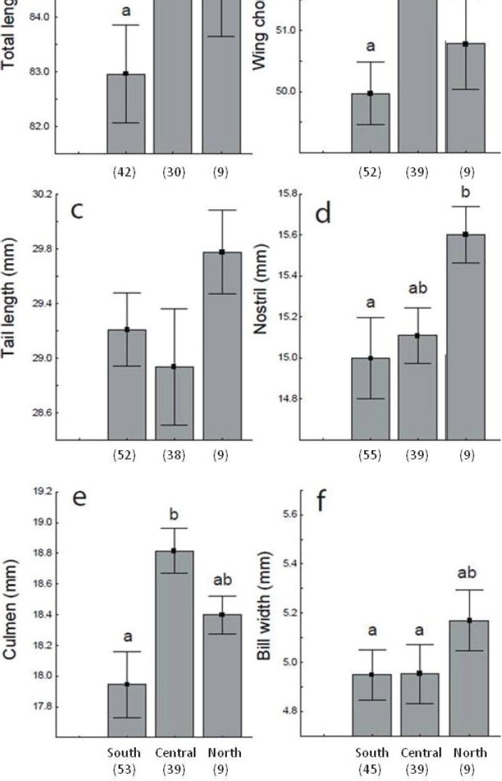

Morphological differences were also found among populations of Hylocharis xantusii along BCP (Fig. 4). Hummingbirds of the southern population were in average smaller considering body size: total length and wing chord traits (Fig. 4a-b) as well as culmen (Fig. 4e) than individuals from central and northern regions. Individuals from central population had larger bills (to culmen) (Fig. 4e) and larger wing chords (Fig. 4b) while hummingbirds from northern population showed wider bills (Fig. 4f), larger bills to nostril (4d) and longer tail (Fig. 4c) compared with other populations. These populations geographically correspond with the genetic populations (South, Central and North) we found for H. xantusii (see figure in González-Rubio et al., 2016). The best-fitted GLM model shows that the altitude and oasis location related to the genetic population correctly explains the differences in tail, wing chord and bill width traits of hummingbirds along the BCP (Table 2, Appendix 1).

Figure 4 Morphological traits (mean ± standard error) among genetic populations (South, Central and North) of Hylocharis xantusii (following González-Rubio et al., 2016). Populations with significant differences in a post hoc test are showed with different letters.

Table 2 Results of the Generalized Linear Models (GLM) showing correlations between sex and morphological traits according to locations (latitude, longitude), oases, altitude and genetic population (Pop). The model that better performed contained the lower AIC value (in bold).

| Model | Coefficients | D2 | AIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Sex vs all variables |

Altitude Pop Oases Tail Wing chord Bill width |

26.63 | 111.67 |

| 2 | Sex vs Morphological traits |

Culmen Tail Wing chord Bill width |

18.98 | 118.07 |

| 3 | Pop vs all variables |

Latitude Oases |

94.62 | 235.09 |

| 4 | Pop vs Morphological traits |

Bill width | 125.15 | 253.34 |

| 5 | Locations vs all variables |

Longitude Oases Pop |

7378.82 | 360.81 |

| 6 | Locations vs Morphological traits |

Culmen Wing chord Bill width |

673.17 | 510.25 |

| 7 | Oases vs all variables |

Altitude Culmen Pop Wing chord |

97 | 342.47 |

| 8 | Oases vs Morphological traits |

Nostril Wing chord Bill width |

85 | 438.32 |

Two-way ANOVA results (Table 3) indicate that populations and sex independently affect the morphological differences in Xantus’ hummingbird. This analysis also showed significant differences among all populations determined by morphological traits, except tail length; only nostril and culmen did not show significant differences between sexes. There was not a significant interaction effect.

Table 3 Summary of two-way ANOVA examining the effect of genetic populations (south, central and north; see Table 2) and Sex (male vs. female) of Hylocharis xantusii on analyzed traits. df= degrees of freedom, MS= mean square.

| Morphological trait | Source of variation | df | MS | F-value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total length | Population | 2 | 37.5 | 6.31 | *** |

| Sex | 1 | 19.8 | 3.33 | *** | |

| Population × Sex | 2 | 12.5 | 2.10 | NS | |

| Error | 69 | 5.9 | |||

| Wing chord | Population | 2 | 40.12 | 6.82 | *** |

| Sex | 1 | 26.96 | 4.58 | *** | |

| Population × Sex | 2 | 3.88 | 0.66 | NS | |

| Error | 69 | 5.89 | |||

| Tail length | Population | 2 | 2.53 | 0.70 | NS |

| Sex | 1 | 8.64 | 2.38 | ** | |

| Population × Sex | 2 | 1.86 | 0.51 | NS | |

| Error | 69 | 3.62 | |||

| Nostril | Population | 2 | 2.37 | 5.52 | ** |

| Sex | 1 | 0.19 | 0.46 | NS | |

| Population × Sex | 2 | 0.21 | 0.49 | NS | |

| Error | 69 | 0.43 | |||

| Culmen | Population | 2 | 4.55 | 7.86 | ** |

| Sex | 1 | 0 | 0 | NS | |

| Population × Sex | 2 | 0.31 | 0.54 | NS | |

| Error | 69 | 0.58 | |||

| Bill width | Population | 2 | 1.23 | 5.22 | ** |

| Sex | 1 | 2.11 | 8.95 | ** | |

| Population × Sex | 2 | 0.18 | 0.77 | NS | |

| Error | 69 | 0.23 |

** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 = statistical significance; NS = not significant.

Discussion

The Xantus´ hummingbird is one of the hummingbird species having colour sexual dimorphism (Howell & Howell, 2000). However, only few studies have quantified directly the sexual dimorphism mainly in North and South America species (Berns & Adams, 2013, 2010; Temeles et al., 2000; Temeles & Roberts, 1993). This is the first investigation showing quantitative differences in morphological traits dimorphism in a species of neotropical origin adapted to arid environments. Our results revealed significant differences in size (total length, wing chord and tail length) and bill width between males and females, males having a larger size.

Mating and social behavior as well as feeding ecology, have been suggested as factors shaping morphological traits to minimize the intersexual competition (Berns & Adams, 2013, 2010; Bleiweiss, 1999; Temeles & Roberts, 1993). For example, in species where males are dominant over females (because of their larger size) and that defend territories, males tend to have a colorful plumage and a wider and straight bill which favor male-male competition and promote the attraction of females (Temeles et al., 2010). Males of Xantus´ hummingbird have a larger body size and display a territorial behavior mainly during the breeding season (authors pers. obs.) and have a bright color plumage. Besides, there is now quantitative support that there is a direct link between dimorphism in bill morphology and sex-specific foraging in other hummingbird species, such that males and females forage on morphologically different resources minimizing the intersexual competition (Temeles et al., 2000). Because males of Xantus´ hummingbird also display a wider bill, it is likely that in this species there are also differences between the sexes in the use of floral resources. However, further research should be done in order to test if our suggestion is true.

The observed differences among the three Xantus´ hummingbird genetic populations in six morphological traits is remarkably as these groups inhabit by one side a mesic condition with forests in the south of the peninsula (i.e. Sierra de la Laguna) and by the other, similar mesic conditions in all other oasis surrounded by the desert. Some ecological hypotheses have been proposed to explain patterns of morphological differences, such as the influence of sex-specific divergence in response to environmental gradients related to the number of nectar-producing plants which shows marked seasonal variation (Brown & Bowers, 1985; Rappole & Schuchmann, 2003). In general, 90% of food requirements for hummingbird species derives from nectar. This level of dependence on a single food type places intense fitness pressure on the individual to locate reliable sources for this item sufficient for survival and/or reproduction; in this way, hummingbirds must adjust and balance their ability to take advantage of resource concentration in both space and time to maximize fitness (Rappole & Schuchmann, 2003). This should be certainly more important in harsh environments with seasonally dry regions (e.g. arid peninsula), where species may exhibit morphological patterns that reflect evolutionary adaptations to local conditions, for example, for mutualistic interactions with bird-pollinated flowers (Brown & Bowers, 1985). Xantus´ hummingbird has a mutually dependent relationship with other endemic species, such as the endemic madrone Arbutus peninsularis in the Sierra de La Laguna in the Cape Region (Arriaga et al., 1990). Outside the Sierra de La Laguna there are no studies that indicate some other mutualistic relationship.

The body size and morphological differences are not result only to the social behavior (defense of territories), mating systems (sex intraspecific competition, female selection) or ecological constraints (resource availability). Wing chord, body size (total length) and body mass might be particularly influenced by environmental conditions (e.g. warm and cold conditions, and low and high elevations) due to flight and physiological limitations associated with these traits, that can cause morphologic differences, promoting local variations and consequently differences at population level (Graham et al., 2012). This condition has been observed in many temperate and tropical hummingbird species (Weinstein et al., 2014; Graham et al., 2012; González et al., 2011). However, in an originally tropical-temperate species posteriorly adapted to a desert condition (e.g. Hylocharis xantusii in the BCP) these hypotheses had not been considered before. Here, we observed significant differences among all populations in all traits including those that could be related to flight and physiological ability (wing chord and total length). H. xantusii inhabits areas from sea level up to 1,400 m (Sierra de La Laguna, Cape Region), but is mostly restricted to oases regions (Rodríguez-Estrella, 1997; González-Rubio et al., 2016). The oak-pine forest of Sierra de la Laguna and the oases are the most mesic stable environments along the Peninsula, but outside these regions temperature can rise up 50ºC (Arriaga & Rodríguez-Estrella, 1997; Rodríguez-Estrella et al., 1997, 2005). Thus, temperature and desert condition together with oases distribution of the BCP could play also an important role in the differentiation of populations via their morphological traits. Finally, we want to call the attention to our finding that morphological differences in several traits of H. xantusii were correlated to the distribution of genetic populations (González-Rubio et al., 2016). The evolutionary history of the species throughout the BCP should be certainly shaped by the oases condition and location.

Conclusions

Xantus´ hummingbird endemic of the Baja California Peninsula showed a variation on morphological traits (total length, wing chord, tail length, and bill length and width) among sexes and among genetic populations. In the first case, morphological sexual dimorphism in which males have larger size, differences could be related to mating and social behavior, and differences in the use of floral resources; in the second case, population differences may be due to habitat association, habitat constraints and populations isolation.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)