Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Boletín mexicano de derecho comparado

versão On-line ISSN 2448-4873versão impressa ISSN 0041-8633

Bol. Mex. Der. Comp. vol.41 no.122 Ciudad de México Mai./Ago. 2008

Artículos

Two different approaches in constitutional interpretation with special focus in religious freedom. A comparative study between Germany and the United States*

Geraldina González de la Vega**

** LL. M. and Dr. iur. student at the Universität Heinrich Heine Düsseldorf (Germany) with a Scholarship of Conacyt (México).

* Artículo recibido el 11 de septiembre de 2007

Aceptado el 29 de noviembre de 2007.

Abstract

In this paper I analyze the constitutional approaches that the German Federal Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court of the United States use, in particular, I analyze the approaches they use to solve religion controversies. Particularly, the focus is the way both courts approach to State-Church relations and the possibility of fundamental rights encroachments. The emphasis of the paper is that decisions involving freedom of religion, like many other hard cases, have to be solved in a way in which the judges optimize the interests in stake and not just try to define what the meaning of the norms are or was meant to be.

Key words: Constitutional Interpretation, Religion, United States Supreme Court, German Federal Constitutional Court, Fundamental Rights, Freedom of Religion, Establishment Clause, State-Church Relations, Optimization, Balancing, Practical Concordance.

Resumen

En este trabajo se analizan los métodos de comprensión e interpretación constitucional utilizados tanto por la Suprema Corte de los Estados Unidos, como por el Tribunal Constitucional Federal de Alemania, con especial atención a casos en donde se involucra la libertad religiosa. El enfoque es sobre la forma en que ambos tribunales interpretan las relaciones entre el Estado y la Iglesia y las posibilidades de que éstas limiten o violenten derechos fundamentales. El énfasis de este trabajo se encuentra en la necesidad de que los jueces constitucionales resuelvan este tipo de casos difíciles optimizando los intereses involucrados y no intentando definir cuál es el significado de las normas constitucionales o la intención del Constituyente.

Palabras clave: Interpretación constitucional, religión, Suprema Corte de los Estados Unidos, Tribunal Constitucional Federal de Alemania, derechos fundamentales, libertad religiosa, Estado laico, relaciones Estado-Iglesia, optimización, ponderación, concordancia práctica.

Summary

I. Introduction. II. Interpretative Approaches. III. State-Church Relations. IV. Conclusion and Five Theses. V. References.

I. Introduction

The words that communicate a norm are the building block of a normative clause. Because these clauses are linguistic by nature, we can say that they are constructed out of arguments of reason. In this sense, one could understand law as language. Since a normative clause is constructed with words, it has to be always interpreted in order to understand its meaning and to apply it to a real case. The interpretation can be made by using many tools and different approaches. The interpretation of the law is made in the first instance by the legislator when s/he interprets the Constitution in order to create norms. The law is interpreted also by judges in order to solve a particular case that is presented to them as controversial. Lawyers interpret the law in order to accomplish their jobs like defend, prosecute, study, etc. Peter Häberle has developed a thesis that proposes public interpretation of the Constitution (öffene Gesellschaft der Verfassungs Interpreten, 1975 or Verfassung als öffentlicher Prozess, 1978 among many others). According to this thesis, the law and, particularly, the Constitution is not interpreted only by the parties involved in law making and law application, but also by all the members of a the democratic and pluralistic society, since a critical and democratic society can and should interpret its own law. In this sense, the Constitution is an open instrument of integration.

When a case is brought to court of justice, the parties have already interpreted the law and in that sense, taken a certain position. Normally the complainant has already interpreted that a certain act violated a norm or a number of norms and that this violation hurts his/her rights or interests. The duty of the court is to revise if this interpretation is correct and if so, to give the reason to the party or to propose a third solution. Usually, cases brought to court of justice are contradictory. This means that a case is a contradicting interpretation of a norm or number of norms applying to a certain case, in which normally at least two different and controversial interests or rights have been involved. To put it simply: both parties claim to have the reason about a particular issue concerning their interests or rights. Respectively, the duty of the court is to revise which party has interpreted the norm correctly and to give this party the reason. In this sense, legal justice means to interpret the language of the law, e. g. the judge has to interpret the language of the law by means of legal reasons that justify his/her decision.

The interpretation of the law is not as simple as it seems. One should make a difference between simple norms and constitutional norms (as well as between rules and principles). Generally, it depends on the kind of legal system and the kind of legal culture of each country. Very important issue is also the constitutional history, which gives a special approach to legal concepts within the legal system and particularly to the way of understanding the State organisation, the balance of powers, the relations between the State and the citizens (fundamental rights) and between the citizens themselves, the democracy and the role of the State in international issues.

Legal theorists1 distinguish between easy cases and hard cases. This distinction is introduced, due to the existence of some real (or ideal) cases which could be interpreted in various ways and which cannot be answered in a single correct answer or at least it is very difficult to do so. The easy cases are those for which the subsumtion process is very simple: the facts do not contradict with the norm and there is only one possible answer: e. g. a norm has either been complied/violated or not. The justification of the easy cases causes no difficulties because neither the application of the norm nor the examination of the facts poses any reasonable doubts. On the contrary, the argumentation of the hard cases is not a simple logic process of sumbsumtion. In these kinds of cases the judge has to analyse a series of problems related to the case that according to Atienza should be determined by the following schema:

1. Problems of relevance or which is the norm to apply.

2. Interpretation problems or how should I understand the norm/s applicable to the case.

3. Proof problems or doubts about the facts of the case.

4. Classification problems or doubts if a fact or number of facts were to be taken under a particular concept contained on the norm.

Once the interpreter has determined the problem/s, s/he should clarify if the problem exists because of insufficient or excessive information. Then, s/he has to build a hypothesis for a solution and build new premises. These new premises have to be justified by arguments in favour of the proposed solution and finally, a conclusion according to the subsumtion process with the justified premises should be given. Deontic logics, as well as legal theory, have developed a number of tools that help to justify the arguments supporting a solution by reasons.

Constitutional norms interpretation is also problematic. That is because the constitutional norms are often open texture norms2 and the discretion of the interpreter is higher. Complex societies, developed within democratic institutions tend to face more hard cases. The existence of different convictions and beliefs within a pluralistic society cause controversies in the interpretation of the language of the law. Determining the meaning of a norm, interpreting and relating a norm to the facts vary according to the ideology of the interpreter. Democratic and constitutional countries try to have just and reasonable judges in order to solve these problems by the most impartial interpretation. Normally, hard cases involving philosophy of life, religion or political preferences have no correct answer.

Often, these cases are solved depending on the ideology and values of the judges (within the constitutional frame). The judges will attempt to solve a hard case by following, to a certain degree, the above-mentioned steps. This means that they will look at the facts that adjust to the norm and, in order to stand within the constitutional frame, they have to justify their decision by reasonable arguments, giving the parties what they think is the most objective and constitutional decision.

The constitutional review is the power of a court to evaluate the constitutionality of the law or actions of the public sector. The sense of this power is to preserve the Constitution by which the people agreed to live and organise their Government. Two different paradigms have been developed; one, within the common law system, the Judicial Review and the other, within the civil law system, the Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit. Each constitutional review system was developed in accordance with a different constitutional tradition and understanding.

Traditionally, scholars have said that these two constitutional review paradigms work differently and some times in a contradictory way. These classical differences3 are found in the nature of the constitutional review (concrete or abstract), in their character (incidental or principal), in the type of court (diffuse or concentrated) and in their effects (special or general).

The American system was developed in order to give supremacy to the Judicial Power and it was formulated by the end of the 18th Century. Whereas the Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit was developed in the 20th Century to support the rule of law and, conversely, looked to re-establish the supremacy of the Parliament.

Likewise, the forms of the constitutional interpretation are analysed and differentiated between both classical systems. Typically, it is said that in the Judicial Review system, that is, the system followed by the United States, the courts interpret the Constitution in a more pragmatic way, since the American Constitution is open and abstract. On the other hand, it is said that the German Constitutional Court, which follows the Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit of the civil law system, interprets the German Fundamental Law based on dogmatics and written law, since this norm is written in a more comprehensive and narrow way.

I will try to demonstrate that these interpretation differences and divergences are not plausible in every case and that there are hard cases in which each of these Courts approach in a very different way as expected. That is because, although the constitutional paradigms are based on different values, goals and views, nowadays both constitutional review systems are approximating. This progressive convergence happens not only in the procedural and technical aspects, but also in the methodology to approach the constitutional norms. The existence of the stare decisis principle and the balancing method are some of it's reasons.

Religious issues are among the most common hard cases in contemporaneous plural societies, that is because they are highly controversial and usually the courts are inclined in their decisions to fully argument what the State's role is and in which degree can it intervene in the freedom sphere of the people, that can be translated in a general interpretation of the role of the State and its relation with the people.

Firstly, I am going to analyse what are the differences and the coincidences between the general and the constitutional approaches of the German Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court of the United States to solve controversies. Secondly, to illustrate how these Courts approach in fundamental rights issues, I am going to analyse how the constitutional courts approach generally, and then, specifically in freedom of religion cases; what are the differences and coincidences; how are regulated the relations between Church and State in both countries and what are the common interpretation methodologies the United States Supreme Court (USSC) and the Bundesverfassungsgericht (BVerfG) use in this type of cases.

Thirdly, I will briefly analyse two cases in which the freedom of religion is involved in order to show how the courts approached and support my thesis.

Lastly, I will present a conclusion and five theses that emerge from this paper.

II. Interpretative Approaches

1. General Approach

The way a Court understands4 and approaches a given case is different. In Germany, as well as in the United States, general judicial approaches depart from the same canon: Issue, Rule, Analysis and Conclusion. But the way to understand it and the order of the process is different. The German approach pretends to be syllogistic, one seeks for a pertinent norm and uses the subsumtion methodology. This formal method analyses the characteristics of the case to prove if they comply with the characteristics of the norm (Tatbestandsmäâigkeit). Subsequently, the facts and the problems are analysed and reasonable arguments are offered to justify the conclusions. The American judges work similarly, even though they do not start with the rule. The process is inverted and they start from a decision and they move on to analyse the facts. The judicial practice looks for the truth, though in each country, each court searches for it in particular and different way.

In Germany the jurisprudence is a scientific research and it is formed through academic arguments. The style is scientific, objective, formal and comparative. The use of rules is preferred over discretion, although the interpretation of statutes is an open work because the norms are wide; the clauses are general and abstract so they give an extensive room for variance. In Germany, it is more likely to find general principles than detailed norms.5 The binding of the wording in German interpretation is teleological, the judges look for analogy cases (reduction or restriction), they interpret first the literal meaning but they favour the systematic interpretation, the objective purpose and the history of the rule. The Constitutional Court acts as an institution, the decisions are issued by the institution and not by the persons. The judicial activity is rational, conceptual and ideal. It can be described as a dialectic process.

The judicial process in the United States can be characterised as a more practical process with experience-oriented or common sense arguments. The style is individual, emotional, free or informal and formed by opinions. The use of discretion is favoured over rules. The statutes are detailed; they have precise definitions, concrete situations. The binding of the words in American jurisprudence is textual;6 the judges look first for the plain meaning and for the legislator's intent. There is a lack of analogy. Originality is a favoured method of interpretation and is understood either as the original intent (for the people at that time) or as the original meaning. The Supreme Court's judgements are published as "opinions" that are issued by persons.7 The judicial activity is experience and case oriented.

The constitutional interpretation in Germany and in the United States has to be understood in terms of their respective constitutional structure and history. The conception of law and judicial process in Germany focuses on the idea of law based on the legal positivism or Begriffsjurisprudenz,8 deriving from the fact that Germany has a continental law system. Written codes and regulations, law, as a logical and reasonable system and dogmatics are the trademarks of the German law conception. In this sense, the judicial process is influenced by the classical idea of the judges as the voice of the law.

On the other hand, the American conception of law is a pragmatic one. Its legal history is based more on the real side of the law; therefore the common law system focuses on the case law and the judicial decisions. This conception can be summarized by the quotation of Oliver Wendell Holmes: The life of the law has not been logic, it has been experience. This systemic and cultural difference has influenced also in the constitutional interpretation.9 The spirit of American public law is symbolized by figures like Holmes, Pound, Llewellyn, Cardozo, Frank and Hand, while the spirit of German public law is influenced by legal theorists such as Jellinek, Anschütz, Laband, Puchta and Radbruch. The German constitutional jurisprudence finds its guide in the idealistic rationalism of Kant, Hegel and Fichte and the American constitutional jurisprudence locates its roots in the commonsense realism of Madison, Hamilton and Wilson.

The interpretive methods10 for legal norms that the courts in both countries employ are very similar: Textual, Historical, Teleological and Systematic, together with the "interest balancing", among other methods. The comparative methodology is proposed by some jurists11 as a way to approach other constitutional court's interpretations in order to search for balanced and democratic decisions or to put side by side the opinions in order to search for equity and justice or to enhance and develop freedoms or civil rights. Vicki C. Jackson12 proposes the constitutional comparison as a method to help judges of the Constitutional Courts to aid the deliberative process but also as an accountability method. She acknowledges three models that describe the relationships between domestic constitutions and law from transnational sources: a) The Convergence model, in which the Courts assume the desirability of convergence with other nations' laws; b) The Resistance model, that relishes the resistance of outside influence; and c) The Engagement model, in which courts are informed but not controlled by considerations of other nations' legal norms. She finds that the best model for the American Constitutionalism is the Engagement model,13 because it may help to interrogate the understanding of the Constitution in several ways. Firstly, it may help to understand empirical concerns; secondly, it can shed light on the functioning of the system; and thirdly, it may illuminate the "suprapositive" dimensions of constitutional rights. Moreover, she finds that this model may enhance the ethical engagement and transparent judgements. Finally, the author argues that the comparative engagement model is helpful in hard cases that arise in constitutional democracies, mentioning as an example the public support for religion.

One basic difference between the judicial system in the United States and Germany is the technique of the stare decisis which is a Latin legal term, used in common law, to express the notion that prior court decisions must be recognized as precedents, according to case law. In Germany, the Courts refer to other opinions from previous cases but the stare decisis does not apply.14

2. Constitutional Approach

In Germany, the Constitution or the Basic Law is viewed as a structure. Since the first constitutional decisions, the Federal Constitutional Court [BVerfGE 1,14 (Südwestaat)] characterised the Basic Law as a unit that should be interpreted as a whole, "No single constitutional provision should be taken out if its context and interpreted by itself... [it] should be always interpreted in such a way as to render it compatible with the fundamental principles of the Constitution and the intentions of its authors". This point of view is important in order to understand the interpretative approach in fundamental rights cases. According to Kommers, this concept is traceable to Rudolf Smend's "integration" theory of the Constitution, "Smend regarded the Constitution as a living reality founded on and unified by the communal values embodied in the German nation... the Constitution not only represents a unity of values, it also functions to further integrate and unify the nation around these values".15 This particular view differs from the American constitutional understanding, the main idea of the US Constitution was to organise the federal government, and in this sense the Framers had no "integration" purposes. The US Constitution was designed only to specify the competences and rules of organisation of the federal government, which had at the beginning the only duty to represent the States on international level.16 This idea makes the US Constitution understanding not as values collection or an integration document, but as the rule of Government and the rule of rules, by which the Federal Institutions act. A liberal society inspired the philosophy of this type of Constitution in which the rules act as guarantees, but not as values that try to pull together the society, or form a national culture.

In Germany, on the other hand, the emergence of the Bonner Basic Law had also the purpose to create a new order and to give the post-war society a Fundamental Law that carried out values and hopes for the morally devastated State.17 In this sense, the German Constitution is seen as a unit that departs from the concept of human dignity binding the State power to it and linked with the federal republican, social and democratic Rechtsstaat. These principles are fundamentally regulated in the articles 1 and 20 of the Basic Law, which function like docks for the interpretation and legislative process (statutory, as well as in constitutional amendments). This issue has also a lot to do with the German philosophy and history, in which culture and nation (Zeitgeist) have always played a special role.

By contrast, in the United States the culture founds itself on the liberal principle of laissez-faire. The less State, the better. Together with the idea of integration, but in a social level, this means that in the US the separation between the assignments of the State and the Society is well defined and separated. To put it simple: the integration in Germany is realized in the level of the State (political power and society) and in the US it is realized in the level of the Nation18 (the people that identifies with some shared and common values).

Another important difference between the constitutional comprehensions of both countries is that in the United States the Constitution was a new phenomenon, since it organised from scratch new forms of government (Constitutional, Republican, Federal and Presidential). Also, the United States had the advantage and difference with European countries of having a homogeneous society (it does not existed nobility). In Germany, the constitutional history was a battle in order to create rules to limit the power of the "Royal Centre" (Fürstentum vs. Kaisertum) and of the administration (Citizen vs. State), which ended in the creation of the Rechtsstaat. The federal organisation in both States has little in common and a lot of historical and traditional traces.

Related to this, the conception of the Basic Law as a structural unit has a lot to do with its interpretation and particularly with the method known as praktische Konkordanz or practical concordance, which is similar to what the courts in the United States have been doing, since the 1930s, through the balancing method.19 Through the former, "the constitutionally protected legal values must be harmonized with one another when such values conflict. One constitutional value may not be realized at the expense of a competing constitutional value. In short: constitutional interpretation is not a zero-sum game"20 but it is more like Pareto optimality. 21 The praktische Konkordanz method optimises the values or the principles in conflict in such a way that the Constitution always wins.

On the other hand, there is the balancing methodology of the United States, which according to Aleinkoff, it is the:

Metaphor that refers to theories of constitutional interpretation that are based on the identification, valuation and comparison of competing interests. By 'balancing opinion', [the author] mean[s] a judicial opinion that analyses a constitutional question by identifying interests implicated by the case and reaches a decision or constructs a rule of constitutional law by explicitly or implicitly assigning values to the identified interests.22

This author is particularly critical to the balancing methodology of the Supreme Court because in his opinion the Constitution contains rules that have to be interpreted and explained, therefore, more than assigning values or weights to the rules, the justices should develop a theory of what the rules mean. Also, it is remarkable in this context of comparison, that this author says "the Constitution [of the United States] is a complex document with many kinds of provisions drafted at different times by persons with different goals. [Therefore] a unitary theory of the constitutional interpretation may be elegant, but it is likely to be a distinctly unrealistic approach to the document".23

The German dogmatic has developed what is known as the Verhaltnismäâigkeitsprinzip or the principle of proportionality, which is basic for the fundamental rights interpretation. According to this principle, all the acts of the government may be scrutinized in order to understand if the encroachment of a rule or a right was justified or not. According to Kommers, this principle plays a similar role as the American doctrine of the due process of law24 and it is also applied just like the standards of judiciary review in order to analyse encroachments of fundamental rights.

3. Fundamental Rights: Theory and Interpretation

Just like the constitutional comprehension, the fundamental rights theory about their foundation and interpretation is also different in both countries. While in the United States the rights are seen as individual "defences" against the State, in Germany the fundamental rights are seen in a double perspective: as "defences" (Abwherrechte) but also as objective values.25 This theory based on the ideological unity of the Constitution has been developed thanks to the paradigmatic Lüth sentence of 1958 [BVerfGE 7, 198]. In this decision, the fundamental rights contained in the Basic Law are not only seen as rights (positive, negative and procedural faculties) but also as an objective order of values that radiates the whole legal system. In this sense it is understood that every time that a law is enforced, that the administration takes action, or that a court imparts justice, these fundamental values have to be always acknowledged. And it is the principle of proportionality (Verhaltnismäâigkeitsprinzip) that makes this system work. Every time the legislator creates a law, when a judge solves a case or the administration acts, this principle has to be taken into account.

The principle is a three-step process.26 A State act (taken here as a general concept for any State's branch activity) has to compel the following principles: a) Geeignetheit or suitability, that the act is adapted to the end; b) Erforderlichkeit or necessity, that is the requirement to look for the milder means to that end; and c) Angemesenheit (Verhältnismäâigkeit im engeren Sinne) or reasonability (proportionality in strict sense), that is balancing or weighing between the principles in stake. According to Robert Alexy's theory, it is in the last step where the balancing of the rights or principles is made and it is where it is looked for the optimization of opposed interests. In Alexy's theory steps (a) and (b) are seen as factual, while the last step (c) is seen as the legal balancing of the rights or interests at stake. That means that the rights or the principles should be realized in between the factual and the legal possibilities.27

This process is also done by the Supreme Court of the United States through standards28 used to review the constitutionality of a governmental action. The Supreme Court applies three key standards of review, which are chosen depending on the context of the case. These standards are 1) Mere rationality; 2) Strict scrutiny and 3) Middle-level review. Normally, when fundamental rights are involved in the case, the Supreme Court uses the hardest of the three standards to review the action, the strict scrutiny. By which the governmental action has to satisfy two very tough requirements: a) Compelling objective, the objective being pursued by the government must be compelling (that means not just legitimate) and; b) Necessary means, the means chosen must be necessary to achieve that compelling end, that implies that the concordance between the means and the end must be extremely tight. In the practice, the Court reviews also the c) No less restrictive alternatives, which means that there must not be any less limited means that would accomplish the government's objective just as well.

These three requirements are much alike like the three steps of the principle of proportionality that the German Courts use. Although, it is important to make clear the different sense that the rights have in each system and the role of the State. In the United States the rights are usually understood as limits for the action of the government, they are founded in the nature of the human being29 and they were incorporated to the text of the Constitution30 in order to make clear that the Federal Government31 has to limit their activity when the freedom of an individual is or could be at stake. To illustrate the comprehension of the freedom in the American constitutionalism I quote here a section of Alexander Hamilton's number 84 of The Federalist:

I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and to the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed Constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers not granted; and, on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretense for claiming that power.

In short: While in the United States the rights are recognized as status that existed before the State and as limits before the governmental action, in Germany they imply also cultural or moral values that the Constitution protects and guarantees, but also it promotes. The rights are achieved with the State. One can say that the fundamental rights model32 of the United States is understood as subjective and jurisdictional, the rights exist before the State existed. While the original European model was objective and legislative and the rights exist together with the State or thanks to it. Today, and thanks to the development of constitutional law (constitutional normativity and judicial review fundamentally), the European model is in the middle: the law as well as the rights are based on the constitution. The escape during the decade of the 50's from the "Weimar mistake" developed the understanding of the laws only in accordance with and conditioned by the fundamental rights.

The rights in the United States are seen as barriers and in Germany they are seen also as ideals that involve the whole society. These pragmatic and ideal approaches constitute the basic and general differences between both constitutional systems, as illustrated also by Thomas Paine:33

A constitution is not a thing in name only, but in fact. It has not an ideal, but a real existence; and wherever it cannot be produced in a visible form, there is none. A constitution is a thing antecedent to a government, and a government is only the creature of a constitution. The constitution of a country is not the act of its government, but of the people constituting its government.34

In contrast, for Konrad Hesse, the Constitution implies a system of values that integrates the politic unity and the legal system. In his classical text of Constitutional law,35 Hesse describes the Constitution as a system, in which the State and the society integrate and realize the ideals contained in the Basic Law. He also explains that the Basic Law is the legal constitutional structure of the community, because it contains the guiding principles through which the political integrity is constructed and the State activities are done. The realization or concretization of the Constitution is translated in the realization of these values among, not only the legal order, but also among the community members (Verwirklichung or Konkretisierung). The constitutional theory of Germany is based on the unity of the community and the Constitution, and this is the significant difference with the theory of the United States, in which the "ideal" is a liberal society "without any ties" and a limited and well regulated Government.

III. State-Church Relations

1. Cole Durham's Model (Theory)

The philosophical approaches that influence the constitutional and fundamental rights comprehension also influence the State-Church relations. This is easy to understand if one takes into account the history of each nation. Actually, both nations were shaped by the role of the Church and the faith. The idea of the constitutionalism arises as a result of the conflicts stemming from religious differences and they were often solved or limited by regulating the government structures. Giving rules to the governments was one solution, but the other and more important solution was the recognition of the freedom of religion. Once the separation between the Church and the State was possible; it was brought into constitutional documents the control of the State through laws and the recognition —in a written document— of the freedoms as a way of assuring them. The United States was constituted in the first place due to the religious persecution and intolerance of the pilgrims back in their homeland England; as well as in Germany, at the beginning, the State was organized due to the power of the Catholic Church, and later, thanks to the Peace of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Year's War.36 In both nations the Church has played and important role to its constitution. The classical liberal arguments for toleration and religious freedom helped stabilize the conflicts and found divergent forms of organisation on each country.

According to W. Cole Durham37 religious liberty needs some conditions in order to be guaranteed and properly protected. These conditions are: minimal pluralism, economic stability, political legitimacy and religious respect for rights of those with differing beliefs, which means the willingness of different religious groups and their adherents to live with each other. In Germany and in the United States, the first three conditions are more or less stabile and existent. The problem can be found in the fourth condition: it is a rather contemporary issue the emergence of religious minorities that demand their rights. The majorities38 in both countries belong to Christianity and these groups have to be prepared to be tolerant to differing beliefs. Sometimes they impose rather conscious or unconsciously, their values, traditions, symbols and practices, limiting the minorities. Religious liberty will not be fully actualized in a community when at least one group feels inhibited in actualizing its religious beliefs. The solution for this problem can only be found in the call for tolerance and the guarantee of the freedom of religion through the actualization of the Constitution, moreover that is also a question that remains a responsibility of the representatives of the Churches.39

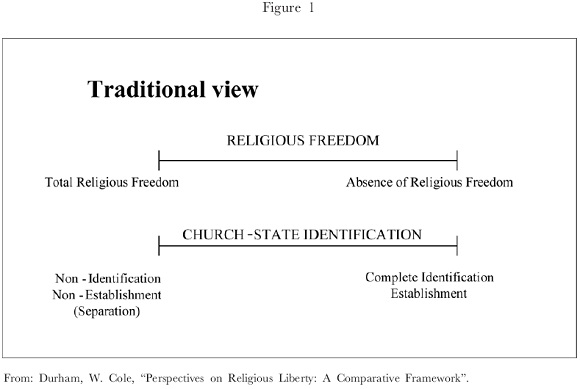

In order to achieve freedom of religion in a constitutional State, the relations between the State and the Church have to be at least clear and sure. Durham proposes a new perspective, he criticises the traditional view40 of the relationship between religious freedom rights and Church-State separation.

There is a tendency to assume that there is a straightforward linear correlation between these two values... [This] oversimplifies matters. The primary difficulties arise in connection with the Church-State identification gradient and its correlation to the religious freedom continuum. Few religious establishments have ever been so totalistic as to achieve complete identification of Church and State. To the extent that extreme situation is reached or approached; there is clearly an absence of religious freedom... At the other end of the Church-State identification continuum... The mere fact that a State does not have a formally established Church does not necessarily mean that it has a separationist regime characterized by rigorous non-identification with religion. Moreover, there is considerable disagreement about the exact configuration of relationships between Church and State that maximizes religious liberty, and it may well be that the optimal configuration for one culture may be different than that for another.41

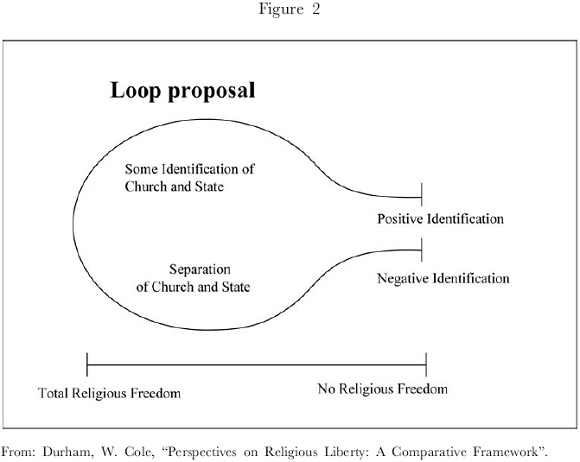

For Durham the complete separation between State and Church does not always mean total religious freedom, since there should be always a relation between religious freedom and the history and culture of the State, as well as the tolerance ingredient that does not assure its existence when there is a total non-identification between State and Church. The problem of this conceptualization lies in the attempt to characterize each country. For example, Durham shows that England has middle levelled State-Church identification and this does not mean that there is middle levelled freedom of religion. To solve this question, Durham proposes:

The answer to this seeming puzzle lies in reconceptualizing the Church State identification continuum as a loop that correlates with the religious freedom continuum... This model accurately reflects the fact that both strong positive and strong negative identification of Church and State correlate with low levels of religious freedom. In both situations, the State adopts a sharply defined attitude toward one or more religions, leaving little room for dissenting views.42

This loop allows the characterisation of each country within open models that show the level of correspondence between the positive and negative identification continuums with no religious freedom and the models in between with different degrees of religious freedom. "Turning to the identification continuum, one can conceive it as a representation of a series of types of Church-State regimes. Beginning at the positive identification end of the continuum, one first encounters absolute theocracies".43 Then the author describes the following models: a) Established Churches, b) Endorsed Churches, c) Cooperationist Regimes, d) Accommodationist Regimes, e) Separationist Regimes, f) Inadvertent Insensitivity and g) Hostility and Overt Persecution. This proposed approach helps to understand the types of institutional configurations and compare them while keeping institutional issues in perspective.

For the purposes of this paper I will focus only on the Cooperationist and the Accommodationist regimes since these are the models that, according to the author, characterise Germany and the United States, respectively.

The Cooperationist Regime According to C. Durham this type of regime:

Grants no special status to dominant Churches, but the State continues to cooperate closely with Churches in a variety of ways. Germany provides the prototypical example of this type of regime... [t]he State may provide significant funding to various Church-related activities, such as religious education or maintenance of Churches, payment of clergy, and so forth... The State may also cooperate in helping with the gathering of contributions (e. g. the withholding of "Church tax" in Germany). Cooperationist countries frequently have patterns of aid or assistance that benefit larger denominations in particular. However, they do not specifically endorse any religion, and they are committed to affording equal treatment to all religious organisations... It is all too easy to slip from cooperation into patterns of State preference.44

In Germany the relations between the Church and State are largely regulated through the Basic Law (GG):

The Article 4 is the centrepiece45 where the freedom of religion is recognized, protected and guaranteed:

I. Freedom of faith, of conscience, and freedom of creed, religious or ideological (weltanschaulich), shall be inviolable.

II. The undisturbed practice of religion is guaranteed.

III. No one may be compelled against his conscience to render military service involving the use of arms. Details shall be regulated by federal law.

In its Article 4, the Basic Law regulates the freedom of religion (number I), anti-Establishment Clause (number II) and the objection of conscience (number III). Taking into account the German theory of the unity of the Constitution, these rights are protected together with Articles 5 freedom of speech; 9 freedom of association; 2 personal inviolability; 6 (2) right of upbringing and care of the children; 7 (2) right of the parents to have their children educated in the faith of their choice and 7 (3) religion class. These rights together with the Article 140 that incorporates to the Basic Law the Articles 136, 137, 138, 139 and 141 of the Weimar Constitution (WRV), which regulate the relations between the Church and the State, being basic the text of the Article 137 (I) "There shall be no State Church". These articles are the core of the non-establishment provision and the basic regulation of the Religionsverfassungsrecht or religion constitutional laws.46

On the other hand, the Accommodationist Regime is:

A regime [that] may insist on separation of Church and State, yet retain a posture of benevolent neutrality toward religion. Accom modationism might be thought of as cooperationism without the provision of any direct financial subsidies to religion or religious education. An accommodationist regime would have no qualms about recognizing the importance of religion as part of national or local culture, accommodating religious symbols in public settings, allowing tax, dietary, holiday, Sabbath, and other kinds of exemptions, and so forth.47

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution recognizes and guarantees the freedom of religion, it determines the so called Establishment Clause, and also it protects the freedom of speech, assembly and the right of petition.

First Amendment: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The Establishment Clause prohibits any law respecting the establishment of religion and its main purpose is to prevent the government from endorsing or supporting religion. The overall intention of this clause is to put a wall between Church and State, so the government stays out of the business of religion and the religious groups stay to some extent, out of the business of the government.48 On the other hand, the free exercise clause bars any law prohibiting the free exercise of religion and its main purpose is to prevent the government from outlawing or seriously burdening a person's pursuit of whatever religion (and whatever religious practices) s/he chooses.49 These two clauses protect the negative and positive liberty of religion and are also applicable to the States through the Fourteenth Amendment's due process clause. When both clauses enter in conflict, the free exercise clause dominates.

2. The Interpretation of the Norms Regulating the Church-State Relations (the Cases)

A. The Crucifix Case50

This case, brought to the German Federal Constitutional Court (BVerfG), attracted a great deal of public attention. Bayern is the most heavily Roman Catholic State in Germany, and after the decision many politicians and Church representatives manifested their disagreement. "The duration and the intensity of the protest worried Germany's judicial establishment. The German Judges Association warned that the rule of law was at stake and that any refusal to obey the Crucifix ruling would endanger the Federal Republic's constitutional democracy. The Judge Dieter Grimm published a letter in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung titled 'Under the Law. Why a judicial ruling merits respect'".51 Even the former Chancellor Helmut Kohl qualified the decision as incomprehensible.

This case was argued in 1995 before the Bundes - verfassungsgericht. The complainant is a family that considers their freedom of religion violated by the Government of the State of Bayern. Through a Constitutional Complaint (Verfassungsbeschwerde) they challenged a School Statute (Volksschulordnung) that is a legal regulation issued by a Bavarian State Ministry.

The Children of the complainants (1 and 2) named in the body of the decision with the numbers 3, 4 and 5 are school-age minor children. The Parents are followers of the anthropophilosophical philosophy of life and they bring up their children accordingly. The family has been objecting through many years to the fact that in the schoolrooms attended by the children first, crucifixes, and later, in part crosses without a body have been affixed. The complainants assert that through these symbols, and in particular through the portrayal of a "dying male body", the children are being influenced in a Christian direction; which runs contrary to their educational notions, in particular to their philosophy of life.

The affixation of the crucifixes and the crosses were supported by § 13(1), third sentence, of the School Regulations for Elementary Schools in Bayern Volksschulordnung - VSO) of 21 June 1983 (GVBl. p. 597), in which was disposed that a cross is to be affixed in every classroom in the public elementary schools. The Volks- schulordnung issued by the Bayern State Ministry for Education and Cultural Affairs, based on a power delegated in the Bayern Act on Education and Public Instruction (BayEUG) and in the (since repealed) Elementary Schools Act (VoSchG). § 13(1) VSO reads: The school shall support those having parental power in the religious upbringing of children. School prayer, school services and school worship are possibilities for such support. In every classroom a cross shall be affixed. Teachers and pupils are obliged to respect the religious feelings of all.

The complainants brought a constitutional complaint directly against the orders issued in the summary proceedings and indirectly against § 13(1), third sentence, VSO. The complainants object to infringement of their fundamental rights under Art. 4(1), Art. 6(2), Art. 2(1) and Art. 19(4) Basic Law.

The majority opinion of the Court was joined by Judges Henschel, Grimm, Kühling, Seibert and Jaeger. On the other hand, Judges Siedl, Söllner and Haas filed a dissenting opinion.

The decision of the BVerfG can be summarized as it follows:

a) First premise (Norms)

The Court analysed the extension and description of the freedom of religion (art. 4.1 Basic Law) and parental right to educate and bring up their children (art. 6.2 Basic Law).

b) Second premise (Facts)

The Court analysed the affixation crucifixes and crosses supported by § 13(1), third sentence, of the School Regulations for Elementary Schools in Bayern Volksschulordnung - VSO) and together with it, the court took into account the following facts:

Fact 1: Exposure and effect of the Crucifix on children.

Fact 2: Purpose of education in public schools.

Fact 3: Meaning of the Crucifix or Cross.

c) Balancing (praktische Konkordanz)

The BVerfG balanced between the following principles of the Basic Law in order to optimize the rights of the complainants, the majority of parents and pupils and the State's educational mandate.

Principle 1: Rights of the Complainants.

Principle 2a: State's educational mandate (art. 7 Basic Law).

Principle 2b: Freedom of religion of the other parents and pupils.

Conclusion: The limitation to the freedom of religion on it's negative aspect is not justified by the principles 2a and 2b, because a State that obliges parents to send their children to State schools may give consideration to the religious freedom of those parents who desire a religiously cast upbringing. Art. 4 (1) Basic Law does not confer on the bearers of the fundamental right an unrestricted entitlement to activate their religious convictions in the context of State institutions. Public schools cannot treat its task in the religious and philosophical area in missionary fashion, nor claim any binding validity for the content of Christian beliefs. The affirmation of Christianity accordingly relates to acknowledgement of a decisive cultural and educational factor, not to particular truths of faith. But Christianity as a cultural factor includes the idea of tolerance for the other-minded.

In this case it is very clear that the BVerfG solved the case by optimizing the rights of all the parties involved. Particularly in this circumstances the right of the parents and the other children in the school had to be considered, so that the Court would be able to balance between a negative and a positive freedom of religion, as well as between the majority's and the minority's freedom of religion. The affixation of the cross cannot be justified from the positive religious freedom of parents and pupils of the Christian faith either. Positive religious freedom is due to all parents and pupils equally, not just the Christian ones. The arising conflict cannot be resolved through the majority principle, since the fundamental right to religious freedom is aimed specifically in a way to protect minorities.

Moreover, Art. 4(1) Basic Law does not confer on the bearers of the fundamental right an unrestricted entitlement to activate their religious convictions in the context of State institutions. [I]t would not be compatible with the principle of practical concordance for the feelings of the other-minded to be completely suppressed in order that pupils of the Christian faith might be able, over and above religious instruction and voluntary devotions, to learn the profane subjects too under the symbol of their faith [the Classroom Crucifix Case of 1995 BVerfGE 93, 1].

So far this case, together with the following are considered the paradigmatic cases on Establishment Clause decided by the Bundes- verfassungsgericht:

a) The School Prayer Case of 1979 [BVerfGE 52, 223].

b) The Interdenominational School Case of 1975 [BVerfGE 41, 29].

c) The Mixed-Marriage Church Tax Case I of 1965 [BVerfGE 19, 226].

d) The Osho Case of 2002 [BVerfGE 105, 279].

e) The Schächten Case of 2002 [BVerfGE 104, 337].

f) The last52 disputed Jurisprudence on this matter was the Head- scarf Case of 2003 [BVerfGE 108, 282].

As shown above, in some cases the German Constitutional Court solves questions about religious liberty and Church-State relations in a more pragmatic way and much less interpretive than the methodology that the Supreme Court of the United States seems to prefer.53 This means that the BVerfG tries to optimize every interest in conflict taking into account every fact and balancing the rights and values protected by the Basic Law in a unitary way. The Court has recognized both the negative and positive characters of religious freedom in its jurisprudence, but also considers other rights that the Constitution protects and that in each case are related to the exercise of the religious freedom. In its decisions, like in the analysed Crucifix Case, the BVerfG applies also democratic values, such as minority rights. They are inclined to use a holistic interpretation methodology by which all the constitutional values are taken into account.

According to David M. Beatty54 the analysis of the German Constitutional Court begins with and is grounded in the relevant constitutional text, but they rely more constantly on the facts of the case and the consequences of a decision and in particular to the details of the laws which constitutional integrity has been attacked. Exactly like the BVerfG did in the examination of the facts in the above-analysed Case. This is particularly clear with the proportionality principle and the principle of practical concordance that the Court applies. "As a practical matter, State neutrality can be defined by a single principle of proportionality or mutual toleration".55 The pragmatic approach helps to judge whether the justifications that State authorities offer for the laws they enact, meet basic tests of legitimacy that are immanent in all constitutional texts. This approach also takes into account the different interests that may be affected by the decision, as well as the consequences of all the possible decisions (Folgenorientierte) .

The practical concordance method is defined in the above analysed Crucifix Case as the method according to which "none of the conflicting legal positions [is to] be preferred and maximally asserted, but all [are to be] given as protective as possible an arrangement".56 With this more pragmatic and consequential approach, the courts determine if the justifications of State authorities meet basic tests of legitimacy that are immanent in the Constitution.

The most profound difference in the two approaches [the German and the American] is that instead of looking to the constitutional document to provide definitive answers to hard practical questions..., the Federal Constitutional Court deduces formal principles like 'practical concordance' from the text which it then uses to evaluate the relevant interests as impartially and objectively as it can. In sharp contrast to the American practice of analysing positive (free exercise) and negative (anti-establishment) claims of religious freedom under separate parts or categories in the Constitution, the German method is to rely on the same principles to evaluate and reconcile the competing interests at stake regardless of whether the claim is cast in positive and negative terms and regardless whether those defending the action of the State rely on the well being of the community at large or on the rights of some of its members. Practical, fact specific reasoning, rather than interpretative insight, is how the Germans decide whether someone's religious freedom has been violated or not.57

B. Mc. Creary County v. ACLU Kentucky58

The issue in this case is whether two Kentucky Counties (Mc Creary County and Pulaski County) violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment through government-sponsored displays of the Ten Commandments in their courthouses. The suit was brought by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Kentucky to the Federal District Court in November 1999. The Federal District Court decided that the purpose of the display was religious rather than secular one. The Counties appealed to the 6th Circuit, which affirmed stressing that under the case "Stone" , displaying the Commandments bespeaks a religious object unless they are integrated with other material so as to carry a "secular message". The Counties appealed and in 2004 the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear the case and ruled on June 2005. The decision of the high court was:

Displaying the Ten Commandments bespeaks a religious object unless they are integrated with other material so as to carry a "secular message". The court saw no integration here because of a lack of a demonstrated analytical or historical connection between the Commandments and other documents. The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment was violated.

The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari and in the majority opinion59 is prevented that the development of the presentation of the Ten Commandments should be considered when determining its purpose. They also argued that the First Amendment contains no textual definition of what establishment means, "[I]t covers a variety of issues, as well as the fact that the First Amendment has two clauses tied to religion: the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause, and sometimes these two clauses compete".

The main argument bases on the principle of neutrality: "Given the variety of interpretative problems, the principle of neutrality has provided a good sense of direction: the government may not favour one religion over another or religion over irreligion, religious choice being the prerogative of individuals under the Free Exercise Clause".

The arguments that preceded the conclusion can be summarized in the following way:

a) Factual Premises: The Counties posted displays with religious content (Ten Commandments). The context of the displays was changed two times, but none of them had a clear secular purpose. The history of the modifications shows abuse of discretion and an apparent litigation position.

b) Normative Premises: The Establishment Clause forbids government to endorse religion. The principle of neutrality is not clear, but there are approaches of interpretation. The precedent cases are: Stone, which is basically the only legal benchmark, along with the Lemon test (see page 32) that the lower courts used to proof the purpose of the displays.

c) Conclusion: The intention of the Counties in advancing religion is clear. The purpose they allege based on the modifications of the displays and their contents is not serious, and could be a sham. There is no neutrality on their purposes. The displays are unconstitutional.

The concept of the Establishment Clause has been determined through Court's decisions as well as scholars. The governmental actions that are "clearly" forbidden by this clause are: an official Church, going to Church or encouraging the worship, the preference of one religion over another and the participation in religious affairs. In order to analyse the governmental action challenged in a court of justice, the Supreme Court has developed60 a number of tests or standards to find out if a government act violated the freedom of religion or the Establishment Clause. Formally the Supreme Court has not adopted an historical approach, but their opinions continue to rely on history and tradition.

Through the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court one can find the following standards, whose benchmark is the 1947 decision of Everson v. Board of Education. In this decision, the Court extended the Establishment Clause jurisprudence to the States through the Fourteenth Amendment. Also, in this decision the concept of "wall between Church and State"61 was adopted by the Thomas Jefferson's quotation and is commonly cited since then.

• The "Schempp test"62 (1963) which attempted to reconcile the Free Exercise Clause with the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment through a two-pronged test, which replaced the "wall metaphor". The first prong is the secular purpose and the second revises that the effect neither advances nor inhibits one particular religion.

• The "Lemon test",63 (1970) which is a three-part test providing that in order to withstand a challenge under the Establishment Clause, the religious display must have a secular purpose; its primary effect must neither advance nor inhibit religion; and it must not foster an excessive entanglement with religion. It seems that recently, in Mc Creary County v. ACLU of Kentucky (2005), the Supreme Court gave the Lemon test a new approach: instead of focusing on the purpose, they focused on the effect.64

• The "endorsement test",65 (1984) is a simpler and more permissive test, under which a display of religious symbols on public property could be successfully challenged under the Establishment Clause only if a reasonable observer of the display in its particular context would perceive a message of governmental endorsement or sponsorship of religion.

• The "coercion test",66 (1989) adopts a broad policy of religious accommodation and is even more permissive, this test only finds a violation of the Establishment Clause if the effect of the governmental action can be said to have the effect in coercing anyone to support, or participate in any religion, or give a direct benefit to religion in such a degree that it tends to establish religion or religious faith.

As it has been mentioned above, the Supreme Court solves the questions about religious liberty and Church-State relations in a more interpretive way.67 This means that instead of taking the facts and approaching the practical matters of each case like the Constitutional Court, the Justices try to develop definitions, concepts, doctrines or rules to apply and, accordingly, to develop what the parameters of religious freedom in America will be. According to Beatty68 these are some of the defining features of the large jurisprudence on the subject of religious rights: The categorical rule like quality of the decisions; The free exercise clause and the Establishment Clause are read as two separated rules; The evolution of the understanding of the religious freedom; The historical record and Supreme Court's own precedents are open to these changes and that means that the interpretations are never settled and secure.69

According to some scholars, in the Mc. Creary case, the Lemon Test had some changes.70 As the Court contested the importance of the use of this test it had substantially reshaped the doctrine by altering the purpose prong. "[A] close look at the Court's formulation of Lemon's purpose prong reveals a critical shift from a search for actual government purpose toward a search for the objective observer's perception of government intent. The Court thereby effectively folded the purpose prong into the effects prong...".71 Instead of looking at the government's purpose as offensive to the Establishment Clause, the review focuses on the perception of the government's purpose and the possible effects of a perceived endorsement.

IV. Conclusion and Five Theses

It may seem awkward that the United States Supreme Court uses a more rigid and interpretive approach and that in Germany the Bundesverfassungsgericht relies more on the facts and the consequences using a more pragmatic approach. The legal traditions in both countries would "contradict" theoretically this behaviour. I believe that in order to distribute justice and enact the Constitution the judicative and more over, the constitutional judicial review has to search for an average term in between both systems and between rules and principles.

Decisions involving freedom of religion, like many other hard cases, have to be solved in a way in which the judges optimize the interests in stake and not just try to define what the meaning of the norms is or were meant to be. Choosing between competing conceptions of religion within the public sphere is a matter of political culture or personal preference, and not a question of right or wrong that can be democratically imposed. This is why the role of the constitutional courts should be to maximize the freedom of the people involved in order to balance what is permissible and what is tolerable.

I have explained how the German and American courts approach to the religious issues. The pragmatism of the first and the interpretivism of the second are not indigenous to their legal cultures. That means that courts have chosen their way to solve hard cases according to legal practice and their jurisprudence, but there is nothing in the Constitution or the laws that binds the courts to this or that approaches and moreover, any approach will be compatible with any legal system.

The role of the courts in this matter can turn against popular sovereignty,72 and that is for the reason that courts strike down laws passed by legislators representing people's preferences. The court that only reads and tries to define what the Constitution says and strikes down a law that according to the majority is correct, but for a minority it violates their freedom of religion, invades the popular sovereignty with absoluteness. Cases in which the freedom of religion is involved include normally the negative and the positive faces of this freedom, and therefore, in hard cases, absolute decisions may encroach one of both interests in stake. It is not just a matter of words interpretation, but analysis of the facts, optimization of interests and acknowledgement of the consequences of the decision.

The approaches that German courts use, namely the practical concordance, as well as the principle of proportionality, are integrative methods that analyse not only what the norm says, but what the facts are and what the effects of the decision could be. In this practical sense, German courts are trying to optimize all the interests involved in order to search for the best decision for everyone and allowing the Constitution to fulfil its ideal.

The search of a court to elaborate and extend the meaning of the Constitution eclipses its original purpose: to give justice. Sometimes that can only happen through practical, fact and consequence oriented, reasoned equitable and balanced decisions. For it, we need Dworkin's judge Hercules, " immensely wise and with full knowledge of legal sources".

First Thesis: Hard cases do not have one single correct answer. In order to interpret the constitutional norms accurately, one should make a difference between rules and principles, and between easy and hard cases. Typically, the cases in which the freedom of religion is engaged are hard cases that involve principles, and that is why the courts should fully argument and justify their decisions.

Second Thesis: The constitutional State as a universal standard has to recognize and guarantee general principles and values. A very important method of interpretation nowadays is the comparison between constitutional court decisions of democratic States. The idea to seek in other countries courts the solution of controversial cases is based on accountability principles, as well as in the idea of universal standards of liberty and human rights.

Third Thesis: The constitutional courts represent the values and norms prescribed in the Constitution and not the majorities as the Parliament does. The courts are obliged to search for the truth and to do justice by acting fairly according to the law. The task of a court in the first place is not to develop concepts or dogmatics, but to interpret the Constitution in order to preserve it and to assure the rule of law.

Fourth Thesis: The basic idea of the constitutional judicial review is to protect the rule of law (Rechtsstaat); hence nowadays one can not distinguish between two different systems. The convergence between both systems is a result of the search of fair decisions that also guarantee the rule of law. The Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit was too rigid, whereas the Judicial Review was too lax.

Fifth Thesis: The interpretation model should favour an optimal solution for the parties and for the Constitution (according to Pareto's optimality). The utility of such a model is that when everyone wins, the Constitution wins and vice versa. Neither the American Constitution nor the Grundgesetz prescribe how should they be interpreted.

V. References

ALEINKOFF, Alexander, "Constitutional Law in the Age of Balancing", 96 Yale L. J., abril de 1997. [ Links ]

ALEXY, R., "Derechos, razonamiento jurídico y discurso racional", Isonomía, México, núm. 1, 1994. [ Links ]

----------, Teoría del discurso y derechos constitucionales, México, Fontamara, Cátedra Ernesto Garzón Valdés, 2004. [ Links ]

ATIENZA, Manuel, "Las razones del derecho. Sobre la justificación de las decisiones judiciales", Doxa, Alicante, núm. 1, 1994. [ Links ]

BEATTY, D. M., "The Forms and Limits of Constitutional Interpretation", 49 Am. J. Comp. L. 79, invierno de 2001. [ Links ]

BEURSKENS, Michael, "Different roads to success. Approach to legal issues in Germany and the US", Conference Law & Language, Düsseldorf, del 17 al 19 de mayo de 2006. [ Links ]

BÖCKENFÖRDE, E. W., "Die Entstehung des States als Vorgang der Säkularisation", Recht, Staat, Freiheit, Suhrkamp. [ Links ]

DURHAM, W. COLE, "Perspectives on Religious Liberty: A Comparative Framework", found in Jackson, Vicki C. and Tushnet, Mark, A Comparative Model for Analysing Religious Liberty on the Chapter X: "Comparative Constitutional Law" , University Case Book Series 1999. [ Links ]

EMMANUEL, Steven L., Constitutional Law, 19a. ed., Aspen Law & Business. [ Links ]

FERNÁNDEZ SEGADO, Francisco, La justicia constitucional ante el siglo XXI: la progresiva convergencia de los sistemas americano y europeo-kelseniano, México, UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, 2004. [ Links ]

HAMILTON, Alexander; MADISON, James and JAY, John, The Federalist Papers. [ Links ]

HESSE, Konrad, "Grundzüge des Verfassungsrechts", 20 Auflage, C. F. Müller.

HOWARD, William M., J. D., Ph. D., American Law Reports, 5th. ed., First Amendment Challenges to Display of Religious Symbols on Public Property. Originally Published in 2003 in Westlaw. [ Links ]

JACKSON, Vicki C., "Constitutional Comparisons: Convergence, Resistance and Engagement", Harvard Law Review, vol. 119, núm. 109, 2005. [ Links ]

JIMÉNEZ ASENCIO, Rafael, El constitucionalismo, Oñati, IVAP, 2001. [ Links ]

KOMMERS, Donald P., The Constitutional Jurisprudence of the Federal Republic of Germany, 2a. ed., Londres, Duke University Press, 1997. [ Links ]

PAINE, Thomas, Derechos del hombre (Rights of Man: Part 1), Madrid, Alianza Editorial, 1984. [ Links ]

"With History, all things are secular: The Establishment Clause and the Use of History", found in Analysis and Interpretation of the Constitution. Annotations of Cases decided by the Supreme Court of the United States, Senate Doc. No. 108-17. 2002 Edition: Cases decided to June 28, 2002.

ZAGREBELSKY, Gustavo, El derecho dúctil (Il Diritto Mitte), 5a. ed., Trotta, 2003. [ Links ]

Internet sites

www.constitution.org/fed/federa00.htm.

www.gpoacces.gov/constitution/brouse2002.html.

www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/index.html.

Notas:

1 Originally this distinction was made by Ronald Dworkin in Taking Rights Seriously (Harvard University Press, 1978). Such a distinction has been widely accepted in contemporary legal theory. In this case, I will follow the analysis of Manuel Atienza on his paper "Las razones del derecho. Sobre la justificación de las decisiones judiciales", Doxa, Alicante, núm. 1, 1994.

2 A Concept used by H. L. A. Hart (The Concept of Law, 1961, Chapter VII) and that is basic for the analysis of Ronald Dworkin's distintion between principles and rules. Op. cit. , note 1, pp. 22 y ss.

3 More about this in: Fernández Segado, Francisco, La justicia constitucional ante el siglo XXI: la progresiva convergencia de los sistemas americano y europeo-kelseniano, México, UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, 2004.

4 I am using some ideas presented by Beurskens, Michael, "Different roads to success. Approach to legal issues in Germany and the US", Conference Law & Language, Düsseldorf, del 17 al 19 de mayo de 2006.

5 Typical examples for the open concepts (Unbestimmte Rechtsbegriffe) are the "Truth and Believe" (Treu und Glauben) concept in the civil law (§ 242 BGB) or the general clauses of the police law and order law (§ 8 PolG and §14 OBG both of NRW).

6 Although, in statutory interpretation exists a controversy between textualists, who favour the enacted act of the legislative; and purposivists, who on the other hand, favour what the Congress wanted or what the aim of the legislative was.

7 It is very rare that the Supreme Court makes a per curiam opinion. This term means "by the court", and the opinion is made by the Court as a whole and it is opposed to the usual personal statements of the judges. Normally a judge makes an opinion and the other judges either "join it" or "dissent with it". There are not many cases on which the Supreme Court has made a per curiam decision, normally they deal with issues the court views as relatively non-controversial. Recently, Bush v. Gore, 531 U. S. 98 (2000). However, per curiam decisions do not mean that all the judges agree and there can be also dissenting opinions, namely in Bush v. Gore, there were cuatro dissenting opinions.

8 Although I would say that in fundamental rights issues, the BVerfG tends more to the Interessenjurisprudenz. That is because the judges pay more attention to what are the interests in stake, namely through the "Verhaltnismäâigkeitsprinzip" and the "praktische Konkordanz" standards that I am going to analyse later.

9 I follow the analysis of Kommers, Donald P., The Constitutional Jurisprudence of the Federal Republic of Germany, 2nd ed., London, Duke University Press, 1997, pp. 40-49.

10 In both countries it is differentiated between constitutional interpretation and statutory interpretation. In the US there is a classic controversy between judicial activism and it's opposite, the judicial restraint. The interpretation theories in the US range from Originalism (Justice Scalia) and Strict Constructionism (Justice Rehnquist) to the idea of the "Living Constitution" (Howard McBain 1972, or the "Living Tree" Canadian Doctrine). See: Ronald Dworkin's 1977, Taking Rights Seriously and 1988, Law's Empire; Hart's 1961, The Concept of Law; or Neil McCormick's 1978, Legal Reasoning and Legal Theory. In Germany, the constitutional interpretation is also well defined and it ranges between a State orientated interpretation (Böckenförde) and an open or dynamic interpretation (Hesse and Häberle). See: Konrad Hesse's 1966, Grundzüge des Verfassungsrechts der Bundesrepublik Deutschland; E. W. Böckenförde's 1991, Die Methoden der Verfassungsinterpretation and his classic of 1974, Grundrechtstheorie and Grundrechts- interpretation; Peter Häberle's 1970, Öffentliches Interesse als Juristisches Problem; or Horst Ehmke's paper for the VDStRL in 1963, Prinzipien der Verfassungsinterpretation (The mention of these texts, neither for the US nor for Germany, does not pretend to be exhaustive).

11 Also Peter Häberle has proposed to recognize the comparative method as the 5th method (in addition to the classical ones of Savingy) especially for constitutional issues. See for example his Works: Verfassung als öffentlicher Prozess, 1978 and Rechtsvergleichung im Kraftfeld des Verfassungsstaates, 1992.

12 Jackson, Vicki C., "Constitutional Comparisons: Convergence, Resistance and Engagement", Harvard Law Review, vol. 119, núm. 109, 2005.

13 I believe, that in terms of Vicki Jackson's models, Germany uses the Convergence Model, since the reception of the European law, as well as its court's decisions has been gradually regulated by the BVerfG in the Solange I and Solange II, as well as the Maastricht Urteil, the Bananenmarkt-Beschluss and more recently, in the Görgülü decision. These decisions regulate, (in general terms) that the national courts have always to take European laws and decisions into account. European laws have priority over statutory law. The BVerfG has acknowledged also the priority of the European law and courts decisions before the Grundgesetz Although, this issue must be revised case by case, and of course, they must not contradict the GG and the fundamental rights standards.

14 This question is disputed. Indeed in Germany there is no stare decisis rule, but some scholars recognize that the role of the Präjudizien can be understood as an important part of the rule of law (Rechtsstaatsprinzip), since they give security and favour the confidence of the citizens (Rechtssicherheit und Vertrauenschutz) as well as it supports the integrity of the legal system and the equal protection. The §31 of the BVerfG law stipulates that the decisions of the Constitutional Court have the same effects as enacted laws for all the State powers, although for the BVerfG they are not obligatory.

15 Kommers, Donald P., op. cit. , note 9, p. 45. See Smend, Rudolf, Verfassung und Verfassungsrecht, 1928, Staatsrechtliche Abhandlungen und andere Aufsätze.

16 See The Federalist Papers, mainly the numbers 1 to 13.

17 Naturally, this is a simplified way to understand the constitutional theory of both countries. The American Constitutional tradition can be traced back to the Mayflower Compact (the first governing document of Plymouth Colony, drafted by the pilgrims who escaped seeking religious freedom in 1620). Also, the understanding of the Constitution in Germany as a cultural and integration document has to be traced along its particular constitutional evolution during the 19th Century and the Weimar Constitution, which however falls out of the scope of the present paper.

18 In take this idea from Huntington's, Samuel, Who are we? America's Great Debate, 2004. It can be here acknowledged (and opposed to the US understanding) the influence for Germany's "integration ideal" of the State Theory of Georg Jellinek, in which he develops the tripartite theory of the State elements: Territory, Nation and Government. Jellinek, G., Allgemeine Staatslehre, 1900.

19 Aleinkoff, Alexander, "Constitutional Law in the Age of Balancing", 96 Yale L. J., abril de 1997.

20 Kommers, Donald P., op. cit., note 9, p. 46.

21 Alexy, R., "Derechos, razonamiento jurídico y discurso racional", Isonomía, México, núm. 1, 1994. The author understands this in the sense that when you have a multi-objective problem (for example a right vs. another right, or a right vs. a policy) you need to arrange many possible solutions, in order to contemplate all the possibilities in the moment of the decision. So a Pareto optimal solution is the best one, because there is no other solution that improves an objective, without making the other objective worse. See also Hesse, Konrad, "Grundzüge des Verfassungsrechts", 20 Auflage, C. F. Müller, Rdn. 72 and following.

22 Aleinkoff, op. cit. , note 19, p. 946.

23 Ibidem, pp. 1003 and 1004.

24 Kommers, op. cit. , note 9, p. 46.

25 See Böckenförde, E. W., "Grundrechtstheorie und Grundrechtsinterpretation", NJW, 1974.