Introduction

Adolescence is a life stage characterized by the second growth period and according to the World Health Organization (WHO),1it takes place between 10 and 19 years of age. During this period, adequate quantities of energy and key nutrients are needed to avoid negative effects on cognitive performance,2 reduction in somatic growth3 and delay in sexual maturation.4 One of the primary deficiencies is anemia resulting from inadequate iron consumption,5 which leads to poor performance in school or at work, risks during pregnancy or birth and low birthweight. Low consumption of zinc leads to an imbalance in the immune system.6 During this growth period, excess consumption of foods that are high in energy and low in micronutrients, could lead to the development of overweight, obesity and chronic diseases in adulthood.7

In Mexico, according to the 2006 National Health and Nutrition Survey (Ensanut 2006), 30% of adolescents had deficient consumption of energy, zinc, vitamin A, folate and calcium. In addition, 35% had excess weight8 and poorest families had high consumption of foods that are high in energy and low in micronutrients and fiber, as sugary drinks, alcohol and some industrialized foods. Given the relevance of micronutrient deficiencies during adolescence, due to the immense demand for nutrients,9 it is fundamental that the consumption of the adolescent population is monitored nationwide. The objective of this study is to estimate the intake and percent adequacy of energy intake (macronutrients, minerals), as well as their prevalence of inadequacy, in Mexican adolescents from Ensanut 2012 using a FFQ.

Materials and methods

Data from the Ensanut 2012 survey was analyzed. This is a multi-stage, probabilistic, stratified survey with national, state and urban and rural representation, with a response rate at the household level of 87%. A semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (SFFQ) was applied to 11% of the sample. More details are described in a previous publication.10 Dietary information was obtained from 2203 adolescents (12 to 19 years old).

Data collection and construction of variables

Diet. Dietary data were collected through a SFFQ that was based on the SFFQ used in Ensanut 20068with 39 additional foods. In total, information on 140 foods and drinks was obtained. The data collected included the number of days, times per day, portion size and number of portions consumed during the seven days prior to the interview. The SFFQ was applied by personnel who were trained and standardized on information collection and recording. SFFQ was validated against 24 hours recall in adolescents and it is a suitable tool to estimate energy and nutrient intakes and rank subjects according to their intakes.11

Intake. Grams (g) or milliliters (ml) consumed per day was obtained for each food and beverage. Consumptions of foods over 3 standard deviations were eliminated. The nutritional content was obtained using a nutritional composition table compiled by INSP.* Grams consumed and nutritional content were obtained using an algorithm in Access with SQL programming.

The database was then cleaned excluding 176 adolescents with an average intake to estimated requirement ratio greater than 3 standard deviations of the mean,12 and 66 pregnant or breastfeeding female were also excluded.

Food groups intake. Food and beverages were classified into 23 food groups: Corn products, tortilla, legumes, wheat products, sweetened cereals (industrialized cookies and cakes, sweetened cereals ready to eat) , ready to eat cereals with fiber, other cereals and roots (rice, potatoes, sweet potato), fruits, vegetables, meats (beef and pork), processed meats (ham, sausage), chicken, fish and shellfish, alcoholic beverages, low-fat dairy, whole dairy and egg, fats (oils, margarine, butter, mayonnaise, cream), candies, salty snacks and desserts, sweetened beverages (juices, tea or coffee with sugar, sodas, sugary drinks), non-sweetened beverages, plain water, sweetened low-fat dairy beverages, sweetened whole dairy beverages and fast food & fried Mexican dishes. Consumption in grams and energy were estimated by food group.

Adequacy percentage (AP). The adequacy percentage for energy was derived from the estimated energy requirement (EER) using the equations from the United States Institute of Medicine (IOM)13 for maintenance of body mass. For adolescents with a lean, overweight or obese nutritional status, the corresponding weight for height was assigned to a normal nutritional status according to the WHO growth standards.14 IOM EER equations require a specific physical activity coefficients, so sedentary level for female and low activity for male coefficients were used according to previous reports in the Mexican population.15,16 For protein, calcium and zinc, the IOM estimated average requirement (EAR) was used,17,18 adequate intake (AI) was used for fiber.14 For iron, the Mexican recommended intake was used.19

Prevalence of inadequacy (PI). The prevalence of the population with inadequate intake was defined when the AP was less than 100% of the EAR or AI. For carbohydrates it was considered PI if they provided less than 55% of energy; for fat, less than 30% of energy was considered,19 as well as less than 7% of energy from saturated fat, at least 10% for polyunsaturated fats and 13% for monounsaturated fat.19

Geographic region. The country was divided into three geographic regions as they were distributed in Ensanut 2012:10 North, Central and South. Mexico City was incorporated into the Central region.

Urban and rural areas. Locations with a population ≥2500 were classified as urban centers, and areas with a population of <2500 were considered as rural.

Household wealth index (HWI). A HWI was constructed using Principal Components Analysis20 with household characteristics, goods and available basic services: materials used in the construction of the floor, walls and roof, number of bedrooms, availability of water, possession of an automobile, number of domestic appliances (refrigerator, washing machine, microwave, stove and heater) and the number of electrical devices (TV, cable, radio, telephone and computer). The first component that achieved 40.5% of the total variance was selected as the index, with an eigenvalue (lambda) of 3.24. HWI was classified in tertiles.

Indigenous ethnicity. A household was considered indigenous when the household head stated that he/she spoke an indigenous language.

Statistical analysis

The medians, 25 and 75 percentiles of intake and AP for energy, macro- and micronutrients were estimated through quartile regressions adjusted for age (intake only), area, region and HWI, taking into account sample weights. PIs are described with frequencies and 95% confidence intervals obtained using logit models adjusted for area, region and HWI. Data were analyzed using STATA, Version 13.0. Population characteristics and PIs were estimated using the SVY module for complex surveys (Stata Co., College Station, TX).

Results

Data from 1961 Mexican adolescents (12 to 19 years old) representative of around 20.68 million are presented. Two out of every three adolescents live in urban areas, close to 50% in the Central region of the country, 11% lived in indigenous households and 34% were overweight or obese (table I).

Energy and nutrient intake

The energy intake for male subjects was around 2000 kcal/d. Males from rural areas consumed a greater amount of carbohydrates and fiber and a lesser amount of heme iron and vitamin A (table II) than those from urban areas. A high intake of total fat was observed in adolescents of both sexes in the North region (table III). High HWI males had greater daily intake of energy, proteins, total fat, monounsaturated fat, total iron, calcium, zinc but lower intake of fiber compared to males with a lower HWI (table IV).

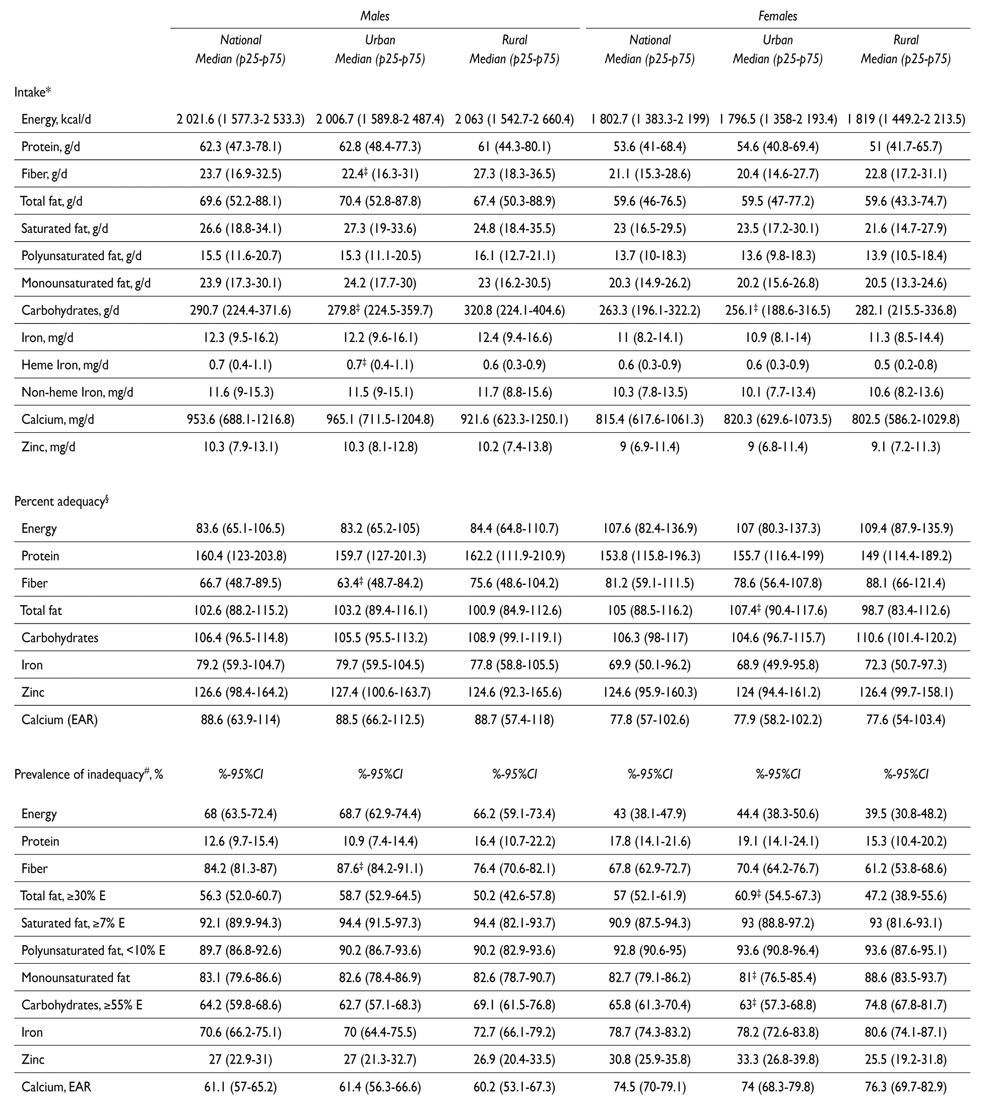

Table II Energy and nutrient intake and adequacy by sex and residence area in Mexican adolescents. Mexico, Ensanut 2012

* Quartile regression adjusted by age, sex, area, region and HWI

‡ Statistically significant differences (p<0.05) between rural and urban area

§ Quartile regression adjusted by sex, area, region and HWI

# Logit regression adjusted by sex, area, region and HWI

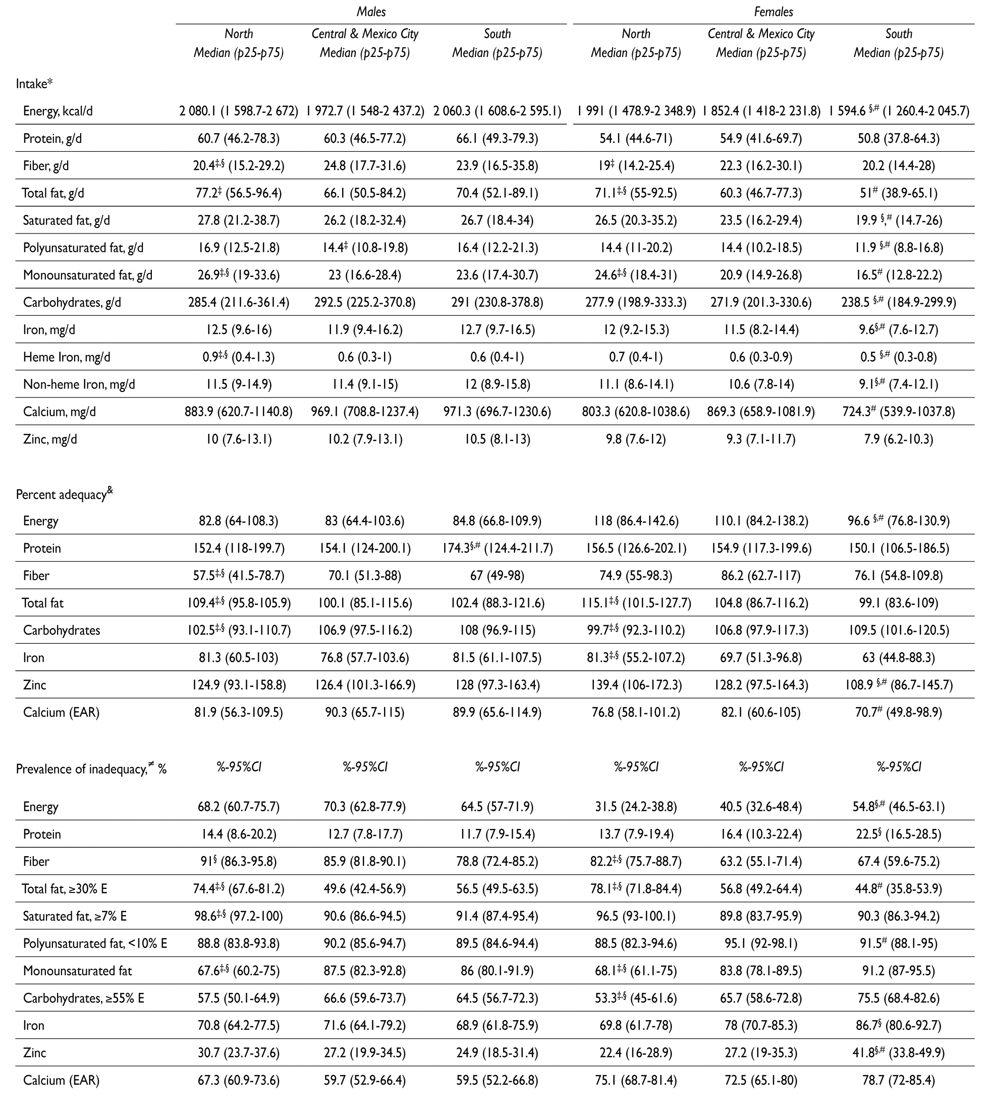

Table III Energy and nutrient intake and adequacy by sex and geographic region

* Quartile regression adjusted by age, sex, area, region and HWI

‡ Statistically significant differences (p<0.05) between north and Central-Mexico City region

§ Statistically significant differences (p<0.05) between North and South region

# Statistically significant differences (p<0.05) between Central-Mexico City and South region

& Quartile regression adjusted by sex, area, region and HWI

≠ Logit regression adjusted by sex, area, region and HWI

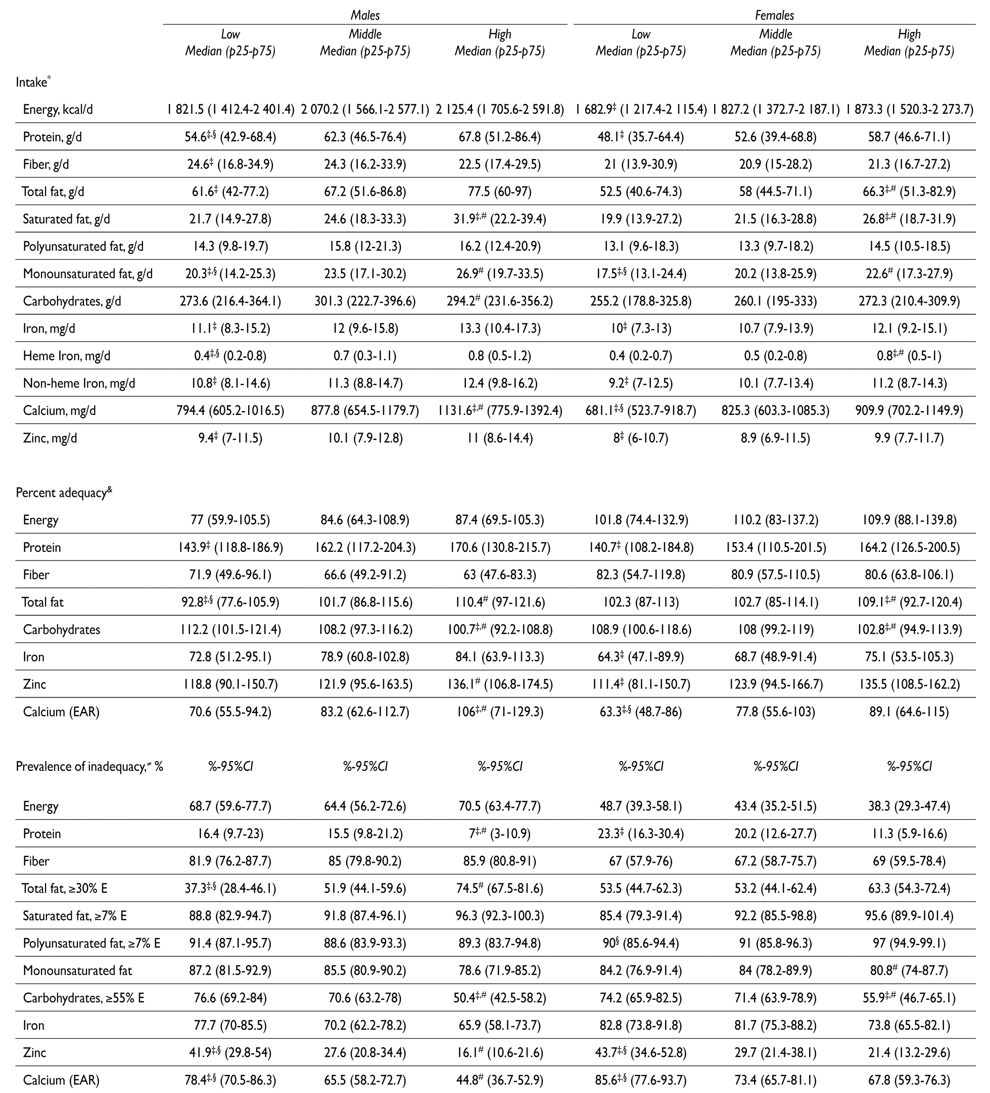

Table IV. Energy and nutrient intake and adequacy by sex and household wealth index in Mexican adolescents. Mexico, Ensanut 2012

* Quartile regression adjusted by age, sex, area, region and HWI

‡ Statistically significant differences (p< 0.05) between low and high socioeconomic status

§ Statistically significant differences (p< 0.05) between low and middle socioeconomic status

# Statistically significant differences (p< 0.05) between middle and high socioeconomic status

& Quartile regression adjusted by sex, area, region and HWI

≠ Logit regression adjusted by sex, area, region and HWI

The energy intake for females was around 1 800 kcal/d. Adolescents from the rural area consumed a greater amount of carbohydrates (table II) compared to their urban counterparts. Females from the Southern región had a lower intake of energy, saturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, monounsaturated fat, carbohydrates, iron and zinc when compared to the Central and Northern regions (table III). Adolescents with a high HWI had greater intake of total fat, saturated fat and heme iron. Meanwhile, those from the lowest HWI tertile had a lower intake of monounsaturated fat (table IV).

Adequacy percentage and prevalence of inadequacy

In males, energy adequacy was around 80%. Nutrients they consumed far above the recommendation were protein and zinc. Males from urban areas had a lower AP for fiber than males in rural areas. Young urban males had greater PIs for fiber than their rural counterparts. In females, energy adequacies were between 7 and 9% above the recommendation. Nutrients that were far above the recommendation were: protein and zinc. Females from rural areas had lower APs for total fat but higher APs for carbohydrates when compared to urban females. Urban females had lower PIs for total fat and higher prevalences for monounsaturated fat and carbohydrates than rural ones (table II).

Males from the Southern region (table III) had a greater AP for protein. In turn, males in the North had a lower AP for fiber and carbohydrates, as well as a higher AP for total fat. Regarding PI, males from the North had a lower PI for monounsaturated fat and higher PIs for total fat and saturated fat. The energy PI was greater in females from the South, who also had lower inadequacies for total fat consumption. Adolescents from the North of the country had the highest PI for fiber and the lowest for monounsaturated fat and carbohydrates (table III).

According to the recommendations, males from high HWI had the highest adequacies for total fat and calcium and the lowest adequacies for carbohydrates (table IV). As with the above findings, males from the high HWI had a higher PI due to excess intake of total fat and lower inadequacies for protein, carbohydrates, zinc and calcium than the middle and low HWI. Females with a high HWI, had the highest AP for total fat; while those from lower HWIs had lower adequacies for calcium. With regard to PIs, females from the high HWI group had lower PIs for carbohydrates; those from lower HWI groups had greater PIs for zinc and calcium (table IV).

Plain water (≈800 g), dairy and non-dairy sweetened beverages (males: 514 g, females: 466 g), tortilla, wheat products, and fruits and vegetables (<270 g) showed the higher intakes. In terms of energy, sweetened beverages, sweetened cereals, candies, snacks, desserts and fast food contributed with 37% of energy intake (table V).

Discussion

This analysis of the dietary intakes of Mexican adolescents showed high PIs of fiber, polyunsaturated fat, iron and calcium; as well as high prevalences for intakes above the recommendations for total fat, saturated fat and carbohydrates. Inadequacies were more often observed in adolescents with low HWI, in the rural areas, and in the Southern region.

Similar results were found in adolescents in the 2005 and 2006 NHANES for calcium.21 As was seen in a state in Brazil, there was inadequate consumption of calcium (>95%), and small differences by gender.22 The mean energy intake was 1 869 kcal for female and 2 198 kcal for male. Of the total energy consumption reported, 57% was from carbohydrates, 27% from lipids and 16% from proteins (37%).

According to the NHANES, average fiber consumption in children/adolescents was 13.2 (± 0.1) g/d.23 In our study, the average intake was 23.7 g/d in male and 21.2 g/d in female. Although this is greater, it is still insufficient to satisfy the requirement.

According to the 2006 National Health and Nutrition Survey (Ensanut 2006),8 there was no significant increase in energy intake for both genders over the last six years. Lower intakes were found in the rural area, the South and among adolescents in the low HWI for iron, zinc and calcium. The adequacy for key nutrients in Mexican adolescents is a fundamental factor for growth and development that may have effects on reproduction and health in adulthood, as well as on the risk of chronic diseases24,25 and effects on health in future generations.1

According to Ensanut 2006,8the national prevalence of anemia in adolescents was 5.6% (95%CI 4.9-6.4), and it was greater in females (7.7%) than in males (3.6%). In our analysis, there were significant differences in PI for iron in the North and South regions in females, which may suggest low intake of sources of heme iron and the presence of non-heme iron absorption inhibitors. Previous publications indicate that the Mexican diet has a low bioavailability of iron (7.5%) with a high amount of iron absorption inhibitors such as phytates, which are found in significant amounts in maize, which is a basic staple food in the Mexican diet.26

Consumption by food groups gives a possible explanation about the high consumption of saturated fats, which could be due to a higher consumption of whole dairy than low-fat dairy. The inadequacy in fiber intake could be related to a lower consumption of fruits and vegetables which were found below recommendations.27 Also, we found a high energy contribution of sweetened or high fat content food groups, including sweetened beverages which were consumption above the recommendation.28 On the other hand, the consumption of plain water and non-sweetened beverages was below the recommendation.

This analysis has some limitations, primarily those derived from the instrument used to measure dietary intake since it was a 7-day SFFQ. Because the period is so short, the season of the year may affect the results; however, the national survey was carried out over a 7-month period (October 2011 to April 2012), so the intake includes a large part of the year on a national level. Although the list of foods included in the questionnaire includes those that cover the diversity of the Mexican diet, it is possible that there is under-reporting of some foods that are highly consumed in some regions or states in the country. It is also possible that the reported intake is affected by factors such as memory, nutritional status and gender.29,30

Underestimations of nutrient adequacies ranging from 1 to 12% were found between the entire sample and those that reported a plausible intake -considered as those within + 1 standard deviation from the mean energy adequacy (data not shown)-. The high prevalence of energy inadequacy (68% for males and 43% for females) should be taken with caution, since underestimation and underreporting of energy intake (up to 38%) is a known limitation of the SFFQ.31

Conversely, some of the strengths of this study are derived from the design of the survey and its representativeness on different levels. Denova and colleagues11 reported an acceptable correlation between the FFQ and a 24-hour recall with a replicate questionnaire in a subsample of Ensanut 2012.

In conclusion, the diet of a representative sample of Mexican adolescents revealed insufficient intakes of some nutrients that are essential for optimal health and an excessive intake of saturated fat. Actions are needed to promote a healthy diet in this population.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)