Dear editor: Deported migrants experience mental health problems,1 and mobility and returning to places with limited services complicate their access to care. Mobile technologies can be useful in this context.2

We conducted a feasibility study3 of a cell phone-administered intervention to promote mental health in deportees. We recruited participants (n=50) in Tijuana, Mexico, from 2015 to 2016, at the point of deportation and in shelters. Eligibility criteria were: 1) <=24 hrs deported; 2) >=3 years in the US; 3) age 20-65 years; 4) Mexico-born; 5) Spanish speaker. Participants received a phone, answered a baseline questionnaire, and were called at 7, 14, 30, 60 and 90 days. During the calls, participants with depressive symptoms received a cognitive-behavioral therapy-based intervention: 1) accepting negative emotions; 2) reflecting on thought patterns accompanying emotions; 3) inventorying resources and making an action plan; 4) relaxation exercise. The caller asked about experience with the intervention (or the phone call). After each follow-up, ≈US$11 were added to phone credit, and there were raffles of gift cards (≈US$28). Our main feasibility outcome was 90-day retention, and we evaluated acceptability and barriers with qualitative data from the calls.

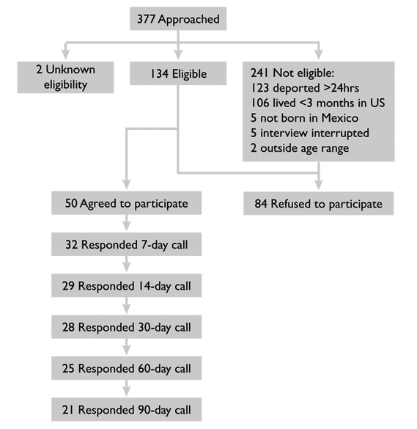

Recruitment rate was 13.3% (50/377) (figure 1). Participation rate was 37.3% (50/134). As per design, 20% of participants were female. Mean age was 35.3 years, average education 8.4 years, and average time in the US 7.3 years. Eighteen percent had a previous diagnosis of depression, and 50.0% had depressive symptoms at baseline. The 90-day retention rate was 42% (21/50). Of the participants, 13/50 (26.0%) responded to five calls, 12/50 (24.0%) to four, 4/50 (8.0%) to three, 2/50 (4.0%) to two, 6/50 (12.0%) to one, and 13/50 (26.0%) to none.

Participants said the calls made them feel “like someone cared” and “optimistic.” Those in rural areas had problems with phone reception. Noise and audition problems were also mentioned. A participant who was back in the US said the phone functioned only when close to the international border. Two mentioned that they had felt unsafe when approached by the researchers, but felt more confident with subsequent calls. The relaxation exercise was not implemented, as conditions (people around, noise) were inadequate.

That 50% of participants responded to four to five calls in the midst of moving between states and countries shows that their experience was positive. A future evaluation study is feasible provided that other means of communication are added (to solve the problem of phone reception), and participation rates might increase if conducted in collaboration with the migrant shelters or Mexican personnel at the deportation points, so that potential participants feel safer.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)