Dear editor: Lung cancer (LC) is the number one cause of death among all cancers worldwide1 and in Mexico.2 LC mortality rates in Mexico increased for both sexes between 1970 and 1999,3 but recent studies have shown a favorable decreasing trend.4,5 However, these studies included all ages in the analysis, or specific age groups (30-74, 35-64, 0-80 years of age), resulting in variable mortality rates. Considering that the majority of malignant lung neoplasms (97%) are usually seen in those age ≥40 years it would be more accurate to determine mortality rates in this population. In this letter we compare the age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR) of LC in people of all ages (ASMR-all) vs people age ≥40 years (ASMR≥40), to determine the degree of underestimation if all ages are considered; compare medians of ASMR≥40 for the periods before and after 2008, when new tobacco taxes and laws were implemented in Mexico, to determine their impact on LC mortality, and determine trends of age-specific rates and of ASMR for the period 1999-2014.

De-identified LC mortality and population growth data were obtained from official websites.6,7 ASMR were calculated according to the World Standard Population8 and joinpoint regression analysis9 was used to determine national rate trends. Lung cancer deaths were identified as ICD-10th codes C33 and C34.

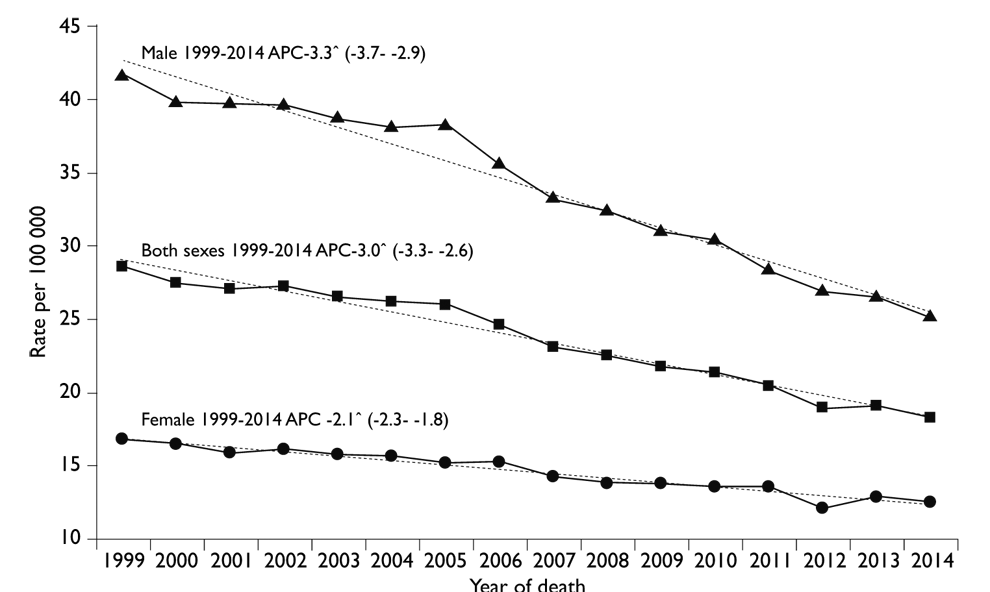

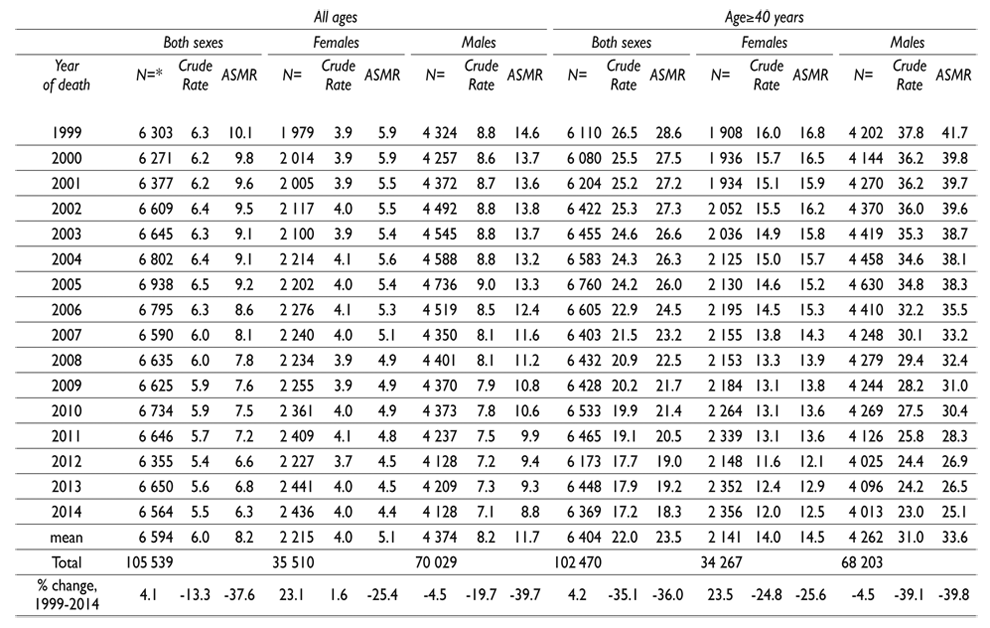

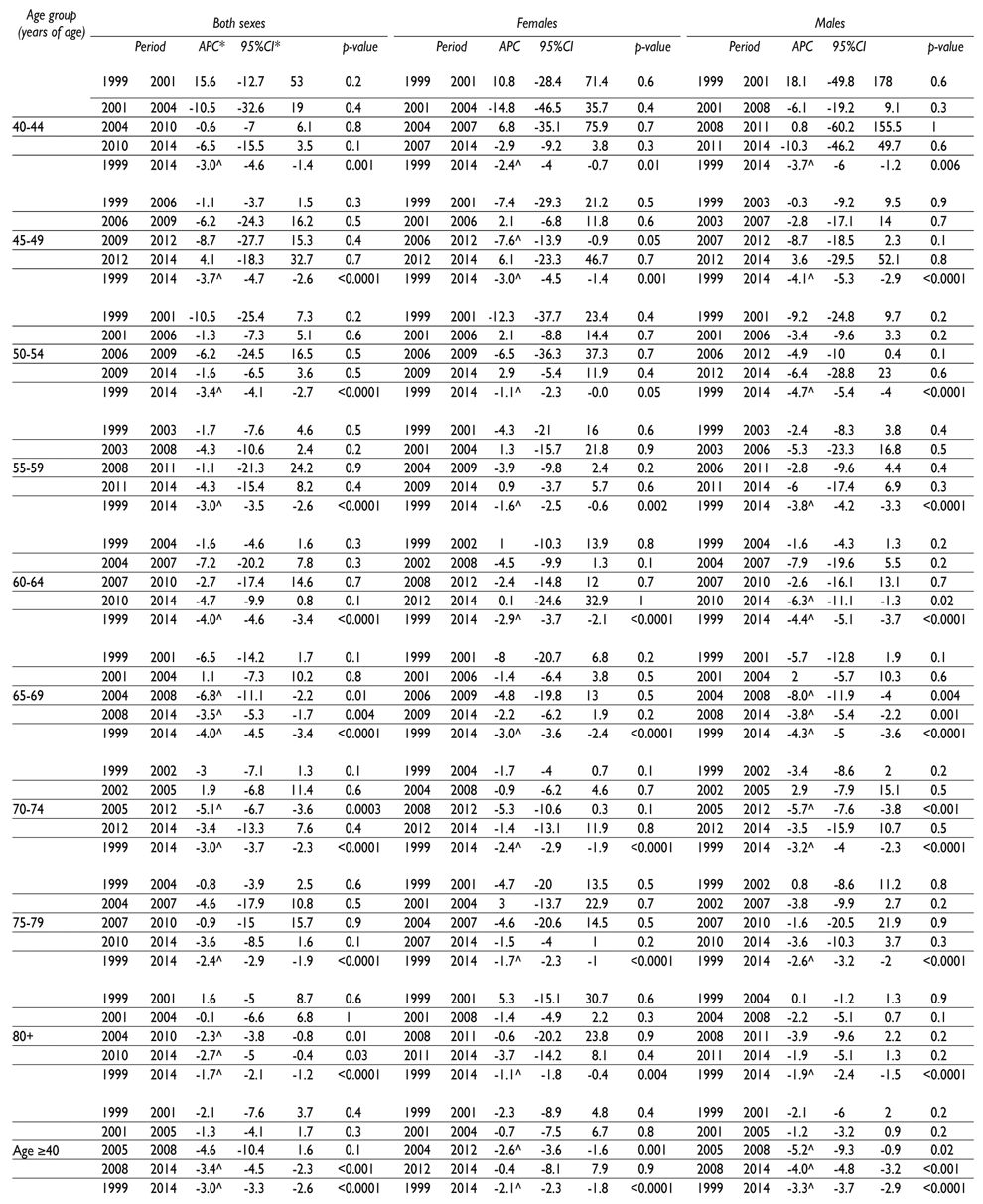

The results showed that ASMR≥40 were about three times higher than ASMR-all (table I). Compared to the first period (before 2008), the ASMR≥40 medians of the second period (after 2008) decreased from 26.6 to 20.5 overall, from 15.8 to 13.6 in females and from 38.7 to 28.3 in males. All changes were statistically significant (p<0.001, data not shown). From 1999 to 2014, the annual percent change (APC) of age-specific rates decreased for the whole sample, for females and for males (table II). The largest decline was seen in males aged 65-69, from 2004 to 2008 (APC -8.0). From 1999 to 2014, the ASMR≥40 decreased 36% in the whole sample, 25.6% in females and 39.8% in males, with an APC of -3.0, -2.1 and -3.3, respectively (p<0.05). Higher APC from 2008 to 2014 were found in the whole sample (-3.4) and in males (-4.0) (figure 1, tables I and II). This study shows that LC’s ASMR will be underestimated about threefold if all ages are considered in the analysis. Trend analysis showed a persistent favorable trend in LC mortality in Mexico, which is likely associated with the implementation of smoking laws and taxes in 2008, and the decrease over time of the prevalence of smoking10,11 and of the use of wood as the main cooking fuel.12 Prevalence of biomass smoke exposure (BSE) resulting from cooking is still high in rural areas of Mexico (44.5% in 2012-201312) and has been associated with lung cancer in Mexican women,13 who usually perform the cooking. BSE may be contributing to the slower pace of decrease in ASMR in women, as they have a lower smoking prevalence than men.

APC= annual percent change (95% confidence interval) by joinpoint regression analysis, ˆ p<0.05

Source: Mexican Ministry of Health, Dirección General de Información en Salud6

Figure 1 Age-standardized mortality rates from lung cancer in Mexico. Age ≥40 years only 1999-2014

Table I Mortality from Lung cancer in all ages and those age≥40 years by gender and year of death. Mexico 1999-2014

* Total lung cancer deaths. ASMR= age-standardized mortality rate. Rates are per 100 000 population

Source: Mexican Ministry of Health, Dirección General de Información en Salud6

Table II Annual percent change estimates by joinpoint analysis of age-specific mortality rates for lung cancer in both sexes, in females and males. Mexico 1999-2014

* APC: Annual percent change,^significantly different from zero at alpha= 0.05,95%CI confidence interval

Source: Mexican Ministry of Health, Dirección General de Información en Salud6

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)