Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Salud Pública de México

versión impresa ISSN 0036-3634

Salud pública Méx vol.53 no.6 Cuernavaca nov./dic. 2011

ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL

Comprehensive evaluation of cervical cancer screening programs: the case of Colombia

Raúl Murillo, MD, MPHI; Carolina Wiesner, MD, MPHII; Ricardo Cendales, MD, MScII; Marion Piñeros, MD, MScIII; Sandra Tovar, Lic en EnfII

ISubdirección de Investigaciones y Salud Pública, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología de Colombia. Colombia.

IIGrupo de Prevención, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología de Colombia. Colombia.

IIIÁrea de Salud Pública, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología de Colombia. Colombia.

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To identify critical screening program factors for reducing cervical cancer mortality in Colombia.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: Coverage, quality, and screening follow-up were evaluated in four Colombian states with different mortality rates. A case-control study (invasive cancer and healthy controls) evaluating screening history was performed.

RESULTS: 3-year cytology coverage was 72.7%, false negative rate 49%, positive cytology follow-up 64.2%. There was no association between screening history and invasive cancer in two states having high cytology coverage but high false negative rates. Two states revealed association between deficient screening history and invasive cancer as well as lower positive-cytology follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS: Reduced number of visits between screening and treatment is more relevant when low access to health care is present. Improved quality is a priority if access to screening is available. Suitable interventions for specific scenarios and proper appraisal of new technologies are compulsory to improve cervical cancer screening. Comprehensive process-failure audits among invasive cancer cases could improve program evaluation since mortality is a late outcome.

Key words: uterine cervical neoplasms; mass screening; program evaluation; cytology; Colombia

RESUMEN

OBJETIVO: Identificar factores críticos para reducir la mortalidad por cáncer cervical en Colombia.

MATERIAL Y MÉTODOS: Se evaluó cobertura, calidad y seguimiento del tamizaje en cuatro departamentos con tasas de mortalidad diferenciales. Un estudio de casos (cáncer invasor) y controles (sanos) evaluó historia de tamizaje.

RESULTADOS: Cobertura 72,7%; falsos negativos 49%; acceso a diagnóstico-tratamiento de HSIL 64,2%. La historia de tamizaje no se asoció con cáncer invasor en dos departamentos con elevada cobertura pero elevada proporción de falsos negativos. Dos departamentos con asociación entre historia de tamizaje deficiente y cáncer invasor tuvieron cobertura aceptable pero bajo acceso a diagnóstico-tratamiento. No hubo relación entre mortalidad y desempeño del programa.

CONCLUSIONES: Reducir visitas entre tamizaje y tratamiento es prioritario ante bajo acceso a los servicios. Incrementar calidad es prioritario si hay adecuado acceso al tamizaje. Intervenciones y tecnologías apropiadas a cada contexto son indispensables para obtener mejores resultados. Vigilar integralmente el cáncer invasor contribuye a la evaluación de los programas por ser un desenlace más temprano que la mortalidad.

Palabras clave: neoplasias del cuello uterino; tamizaje masivo; evaluación de programas y proyectos en salud; citología; Colombia

Cervical cancer incidence and mortality have been reduced up to 80% in developed countries.1 Despite the absence of clinical trials, the relation between Pap-smear screening and reduction of cervical cancer incidence and mortality has been recognized.2

The decreased burden of disease has been attributed to screening coverage leading to increased effort for extending conventional cytology to all women worldwide. Although screening programs have been successful in developed nations, they have not fulfilled their objectives in the majority of developing countries.1,3 In Colombia, cervical cancer remains the first cause of cancer mortality and the second cause of cancer incidence among women.4

The lack of impact of conventional cytology in low and middle income countries has been linked to social and economic factors as well as deficiencies in program organization.5 Recent studies revealed that Pap-smear coverage does not correlate with trends of cervical cancer mortality in Latin America; similarly, for countries in the region with decreasing cervical cancer mortality (Mexico, Chile, Costa Rica, Colombia), no clear association between reported organization of screening program and reduction in mortality rates could be determined.6

The aforementioned situation indicates that screening coverage is not sufficient for cervical cancer control, and highlights the need for better understanding of program components and critical success factors. Accordingly, numerous frameworks for cervical cancer screening program evaluation have been proposed;7-9 but few have been implemented in Latin America, where most evaluations remain focused on screening coverage.6

A model on screening components impact on cervical cancer mortality in Colombia revealed greater influence of follow-up of positive screened women (high grade lesion – HSIL) than did cytology coverage, since proper cervical intraepitelial neoplasm (CIN) treatment, after screening, is the real factor for preventing invasive cancer.10 Conversely, a review of evaluative studies demonstrates that evaluation on access to colposcopy and CIN treatment for HSIL cytological diagnosis is scant in Latin America, and inexistent in Colombia.6,11

In addition, a few countries in the region have reported nationwide information on Pap-smear quality.6 The analysis of cytology quality is challenging due to the abundant indicators and methodologies; however, two major topics might be considered the most influential on screening effectiveness: smear collection quality and ability of the test for detecting CIN.9 The available information shows no major differences in Pap-smear sensitivity between Latin America and Europe and North America,12-15 thus contributing to the lack of understanding about sustained high mortality rates.

Therefore, the National Cancer Institute of Colombia conducted an evaluative study aimed at identifying critical program factors for cervical cancer mortality reduction in the country through analyzing screening coverage, cytology quality, and access to colposcopy and CIN treatment. Every component was evaluated in an independent study; thus, the objective of this report is to combine the results from all components in order to provide a comprehensive analysis of the program.

Materials and Methods

The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee at the National Cancer Institute of Colombia (INC). We conducted an evaluative study analyzing four components: screening services supply, screening coverage, conventional cytology quality, and follow-up of positive screened women. Furthermore, a case-control study to evaluate Pap-smear effectiveness was done.

The study was carried out in four Colombian states selected by combined levels of mortality and screening organization. Two states with high cervical cancer mortality (Caldas and Tolima), and two states with low cervical cancer mortality (Boyacá and Magdalena) were included.16 Of the two high mortality states, one revealed satisfactory performance of cervical cancer screening program but the other was deficient, according to Ministry of Health indicators;17 the same criterion was used for selecting low cervical cancer mortality states (Table I). All four states were included according to feasibility criteria: study affordability, geographical access to municipalities, and security conditions. In total, the four states represent 4 719 116 inhabitants and 1 100 615 women 25-69 from different cultural and social backgrounds.

Detailed methodology and results for each one of the five abovementioned components has been previously described.18-22 To analyze screening services supply three kinds of institutions were considered: Pap-smear collection centers, cytology laboratories, and colpsocopy centers. Pap-smear collection centers were included based on an independent simple random sampling for every state. For cytology labs and colposcopy centers total census was reviewed.18 An audit survey was carried out on human resources availability (nurses, cytotechnologists, pathologists, colposcopists), quality control process, and productivity.

Screening coverage was analyzed through the National Survey on Demography and Health (NSDH).20 A subset of women 40-69 was interviewed, and questionnaires included questions on Pap-smear screening history. NSDH is a national probabilistic household survey representative of every state including rural and urban areas.

Cytology quality was evaluated using a stratified sample of reported Pap-smears in every state (independent universes).19 Three strata were defined: unsatisfactory smears, negative results, and positive results. Selected Pap-smears and correspondent original reports were sent to INC for a second reading by two blinded expert pathologists, using the Bethesda 2001 system. The second reading recategorized Pap-smears as unsatisfactory, non-positive (normal, low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion -LSIL-, ASCUS), positive (ASC-H, HSIL, cancer), and glandular cell abnormalities. If no agreement was initially obtained, both pathologists defined consensus diagnosis. Agreement between original and INC-expert reports was evaluated by Kappa index and correspondent 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Additionally, assuming INC-expert report as gold standard, the proportion of negative results disagreed (false negative) and positive results disagreed (false positive) were estimated for every state.

A sample of women with HSIL or higher diagnosis was recruited to evaluate access to colposcopy and CIN treatment. A structured survey was conducted and medical records reviewed registering information on compliance with colposcopy-biopsy and CIN treatment during six months after the HSIL report, as well as reasons for lack of attendance.21 A two-stage sample was designed independently for every state. The first stage selected municipalities in two strata: those with compulsory inclusion (all having colposcopy centers) and those selected by simple random sampling (without replacement). The second stage selected women with HSIL cytological report: among municipalities with compulsory inclusion women were selected by simple random sampling, and for randomly selected municipalities all women were included.

For the case-control study, fifty women, ages 25-69, with invasive cervical cancer histological diagnosis were randomly selected in every state from all invasive cancer reports; and fifty neighboring population controls matched by age, and without history of CIN, cervical cancer, or cervical treatment.22 A structured survey was conducted and medical records reviewed when necessary to determine history of cervical cancer screening within previous 48 months. Cytology exams for follow-up or diagnosis (symptomatic women) were excluded from analysis.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of Pap-smear collection centers for analysis of screening services supply was estimated to obtain a variance coefficient lower than 10% for any proportion. For screening coverage component, a proportion near 70-80% (3-year) with relative standard error 1-2% was estimated.23 For evaluating cytology quality, sample size was calculated expecting a 5% reading error, relative standard error 80%, 95%CI 3-7%, and 20% of Pap-smears not to be found. To analyze colposcopy and CIN treatment access, the sample size estimated proportions around 30-40% with variance coefficients 20-40%. For case control study, the sample size was estimated based on McNemar test, assuming 80% power, disparity rate 2:3, and proportion of discordant pairs 0.2-0.3.22

For screening services supply, screening coverage, and colposcopy-treatment access, all results are presented as expanded data according to specific weighting factors in sample design. Total and ratio estimates and variation coefficients were calculated. For Pap-smear quality, frequencies and percentages are described, as well as non-weighted Kappa with 95%CI. In the case-control study, a hierarchic conditional logistic regression model was carried out and adjusted paired odds ratios obtained. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software.

Results

In total 859 Pap-smear collection centers (Boyacá 313, Caldas 128, Magdalena 174, Tolima 244), 52 cytology labs (Boyacá 14, Caldas 7, Magdalena 21, Tolima 10), and 99 colposcopy centers (Boyacá 17, Caldas 40, Magdalena 9, Tolima 33) were identified in the four states. According to number of municipalities, Magdalena and Tolima had highest collection centers rate, Magdalena highest cytology labs rate, and Caldas highest colposcopy centers rate (Table I). No major differences on human resources availability were observed among states.

Only Tolima accomplished basic indicators on quality control process. Magdalena and Caldas reported low percentage of positive smears reviewed for quality control (Table I). With the exception of Magdalena, average of smears read annually by cytotechnician surpassed 3000; the highest average of smears by reader was in Caldas (8490.4); however, Caldas revealed lowest average of biopsies per colposcopy (0.4).

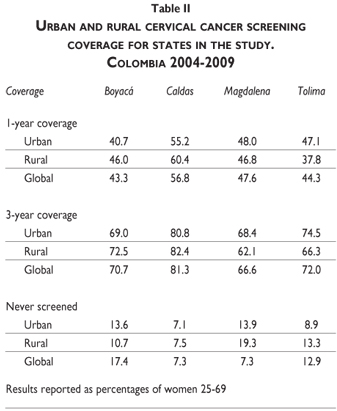

One-year coverage ranged between 43.3 in Boyacá and 56.8 in Caldas; 3-year coverage from 66.6 in Magdalena and 81.3 in Caldas (Table II). Boyacá and Caldas reported higher coverage among rural population, and Boyacá and Tolima highest percentage of women with no cervical cancer screening history (17.4 and 12.9).

Tolima and Magdalena accounted for highest percentage of inadequate smears (13 and 7.5, respectively); and Boyacá and Caldas highest percentage of false negative results (61.1 and 58.8, respectively). Overall percentage of false positive results was low (range 2.4 to 3.8) (Table III). For this component, the sample in Magdalena could not be recruited as planned because only 30.8% of cytology labs stored Pap-smears.

Some 19.4% of women with HSIL did not undergo colposcopy in Boyacá and 1.3% did not remember having colposcopy during the preceding six months. For Caldas these percentages were 19.3 and 9.1 respectively; Magdalena 31.3 and 1.0; Tolima 22.4 and 15.6 (Figure 1A). In total 166 women had indication of treatment in Boyacá, 109 in Caldas, 101 in Magdalena, and 218 in Tolima. From these numbers 17.9%, 5.1%, 4.0%, and 12.4% did not undergo treatment in Boyacá, Caldas, Magdalena, and Tolima, respectively. In summary, in Boyacá 29.4% of women with HSIL cytological report did not access or did not remember confirmatory diagnosis or treatment, Caldas 32.1%, Magdalena 33.5%, and Tolima 41.6% (Figure 1A).

Among women who did not attend confirmatory colposcopy-biopsy, in Boyacá 40% reported reasons related to health services organization or economic barriers, Caldas 50.9%, Magdalena 59.1%, Tolima 60.8% (Figure 1B). The rate of non-response to questionnaire on reasons for lack of attendance among women with indication of preneoplasic lesions treatment was: Boyacá 25.8%, Caldas 18.2%, Tolima 67.9%, Magdalena 0%.

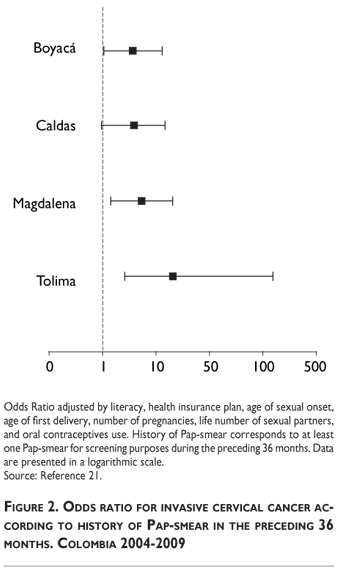

The case-control study showed significant increased risk of cervical cancer according to history of screening in Magdalena and Tolima, but no increased risk in Boyacá and Caldas (Figure 2). There was a significant difference (p<0,01) in average number of Pap-smears between cases and controls during the previous 48 months (Difference 0.45, 0.61, 0.84, and 1.53 for Boyacá, Caldas, Magdalena, and Tolima, respectively).

Discussion

The reduction of cervical cancer mortality following organization of Pap-smear in European countries has driven implementation of screening programs globally; additionally, some cost-effectiveness models show that program organization might be a more efficient way to decrease burden of disease.24 Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) has published guidelines indicating necessary components for an organized program;6 however, many developed nations have largely reduced cervical cancer mortality without meeting WHO standards.25

There is abundant literature describing requirements for organized programs, but few studies evaluating impact of organized screening.26 A meta-analysis revealed that most process failures related to invasive cervical cancer diagnosis are derived from poor screening frequency (low number of Pap-smears or never screened), and only 11.9% are due to poor follow-up of abnormal results;27 however, these data come from developed nations where follow-up is generally guaranteed.

Low screening test sensitivity and lack of correlation between screening coverage and cervical cancer mortality in Latin America6 suggest that successful screening programs depend upon frequent repetition of Pap-smears and permanent access to confirmatory diagnosis and treatment.11 Accordingly, our results revealed a significant association between history of screening and risk of invasive cancer only for Magdalena and Tolima; for the other two states, history of screening did not represent differential risk among women with invasive cancer and population controls (Figure 2). These data indicate occurrence of at least two different settings.

Caldas accounted for highest screening coverage and along with Boyacá showed highest rural cytology coverage. Concordantly, Boyacá and Caldas had the lowest percentage of women without access to confirmatory diagnosis or treatment for HSIL reports. Tolima revealed similar proportion of HSIL without colposcopy than Caldas and Boyacá; but, given the fact that the evaluation included a survey six months after cytological report and review of clinical records, it is highly probable that all women with unknown colposcopy or treatment during this period actually did not undergo these procedures. Results on screening coverage and follow-up of positive screened women suggest association between screening history and invasive cancer in Magdalena and Tolima, due to low health care access. This finding is backed by results on colposcopy barriers, wherein women from Magdalena and Tolima reported higher percentage of problems related to health services organization and economic restraints. Furthermore, no major differences in human resources availability, and no correlation with number of cytology labs or coloscopy centers per municipality were observed among states.

On the other hand, states with ostensibly better access to health care (Boyacá and Caldas) revealed higher negative results disagreement and lower overall agreement between gold standard and original cytology report (Table III). These data and lack of association between screening history and invasive cancer in Caldas and Boyacá insinuate that deficiencies in cytology quality play a more relevant role for these states. Yet, Caldas had lower biopsy/colposcopy rate and higher cervical cancer mortality than Boyacá (Table I); since a correlation between number of biopsies and colposcopy sensitivity has been established, it is possible that the abovementioned low rate decreases CIN detection despite higher colposcopy center availability.

These results are striking since they point towards necessary identification of specific problems and needs for different settings in order to guide more suitable interventions. Conversely, efforts for improving impact of cervical cancer screening in Latin America have been focused mainly on screening coverage without proper program evaluation.6 A cost-effectiveness model for Colombia has demonstrated that increased coverage without access to proper diagnosis and treatment would result in lower decrease of cervical cancer mortality than improved HSIL follow-up, even with limited 50% screening coverage.10 Therefore, alternative approaches to reduce number of visits between screening and CIN treatment seem more appropriate when low access to health care is prevalent. Accordingly, for these scenarios new technologies should be evaluated regarding their capacity to produce immediate results allowing treatment in the same or a subsequent visit. Recent reports also highlight the relevance of high sensitive tests for implementing see-and-treat approaches in low income populations.28,29

Differently, for settings with proper health care access, but screening test quality deficiencies, reduction in number of visits is secondary. Previous analyses from Europe and North America demonstrate that improving Pap-smear sensitivity over 50% is challenging;13 thus, according to our results (negative results disagreement 42 to 61%), a major augment in cytology sensitivity should not be expected. If no improvement in cytology quality could be obtained, new technologies with higher sensitivity and lower quality control requirements ought to be examined.

Separate reports on specific factors influencing every component of screening program in Colombia have been previously published.18-22 Herein we present the comprehensive analysis including all major components as related to invasive cancer diagnosis. A recent review found a few attempts to comprehensively assess screening programs in Latin America. Joint information for screening coverage, cytology quality, and follow-up of abnormal Pap-smears was found only for Chile, Cuba, El Salvador, and Nicaragua; but, just Chile reported results from a comprehensive evaluation while the remaining countries recapped different reports from different sources.6 The Chilean appraisal was based on nationwide routine data recorded by an organized program. Basic criteria for organized cervical cancer screening monitoring have been proposed comprising availability on a regular basis, high quality, meaningful targets as the evidence base builds, measures and established targets that facilitate inter-jurisdictional comparisons, feasibility of regular monitoring, wide acceptability for use in program evaluation, and screening-treatment spectrum coverage.30

Unfortunately, the aforementioned standards are unobtainable for most Latin American countries which do not have organized screening, and only a small number of countries worldwide have published this type of evaluation. Our study was conducted for a nation with no organized screening by combining different independent analyses on the same population. Similarly, a situation analysis was reported for Mexico including Pap-smear collection and reading quality, factors influencing Pap-smear uptake, and case-control study; however, no assessment of colposcopy and treatment access was done, and only Mexico City was included in all components.31

The abovementioned conditions for our study impose several limitations. Due to feasibility restrictions we were able to include only 4 out of 36 states, restraining the possibility of obtaining statistical significance in estimates. Additionally, the absence of organized activities and the lack of regular monitoring challenged the sample calculations and accessibility to medical records and women; thus, troubling data collection on cytology quality in Magdalena and reasons for lack of treatment attendance in the remaining states.

Despite the limitations, a better understanding of screening program performance was possible through our study highlighting the relevance of comprehensive evaluations. Some developed countries have conducted comprehensive audits of cervical cancer screening based on analysis of invasive cancer cases (screening history, negative results, access to colposcopy and treatment), using case control studies occasionally.32-33 Case-control studies provide rapid assessment of screening history, but if no association is found, as in the cases of Boyacá and Tolima, information from other program components, such as false negative screening and women's follow-up, would be required. Accordingly, we consider that implementing strict invasive cervical cancer surveillance, with determination not only of screening history but screening results and access to colposcopy and treatment as well, would be a feasible way to improve program evaluation and understanding in Latin America.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Colombian government through the grant program 41030311-05 at the National Cancer Institute of Colombia.

Declaration of conflict of interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

1. Parkin DM, Bray F. Chapter 2: The burden of HPV-related cancers. Vaccine 2006;24 Suppl 3:S3, S11-S25. [ Links ]

2. Quinn M, Babb P, Jones J, Allen E. Effect of screening on incidence of and mortality from cancer of cervix in England: evaluation based on routinely collected statistics. BMJ 1999;318:904-908. [ Links ]

3. Kitchener HC, Castle PE, Cox JT. Chapter 7: Achievements and limitations of cervical cytology screening. Vaccine 2006;24 Suppl 3:S3, S63-S70. [ Links ]

4. Pardo C, Cendales R. Incidencia estimada y mortalidad por cáncer en Colombia 2002-2006. Bogotá: INC, 2010. [ Links ]

5. Denny L, Quinn M, Sankaranarayanan R. Chapter 8: Screening for cervical cancer in developing countries. Vaccine 2006;24 Suppl 3:S3, S71-S7. [ Links ]

6. Murillo R, Almonte M, Pereira A, Ferrer E, Gamboa OA, Jerónimo J, et al. Cervical cancer screening programs in Latin America and the Caribbean. Vaccine 2008;26 Suppl 11:L37-48. [ Links ]

7. Lazcano-Ponce EC, Buiatti E, Nájera-Aguilar P, Alonso-de-Ruiz P, Hernández-Avila M. Evaluation model of the Mexican national program for early cervical cancer detection and proposals for a new approach. Cancer Causes Control 1998;9:241-251. [ Links ]

8. Madlensky L, Goel V, Polzer J, Ashbury FD. Assessing the evidence for organised cancer screening programmes. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:1648-1653. [ Links ]

9. Marrett LD, Robles S, Ashbury FD, Green B, Goel V, Luciani S. A proposal for cervical screening information systems in developing countries. Int J Cancer 2002;102:293-299. [ Links ]

10. Gamboa OA, Chicaíza L, García-Molina M, Díaz J, González M, Murillo R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of conventional cytology and HPV DNA testing for cervical cancer screening in Colombia. Salud Publica Mex 2008;50:276-285. [ Links ]

11. Gage JC, Ferreccio C, Gonzales M, Arroyo R, Huivín M, Robles SC. Follow-up care of women with an abnormal cytology in a low-resource setting. Cancer Detect Prev 2003;27(6):466-471. [ Links ]

12. Herrero R, Ferreccio C, Salmerón J, Almonte M, Sánchez GI, Lazcano-Ponce E, et al. New approaches to cervical cancer screening in Latin America and the Caribbean. Vaccine 2008;26 Suppl 11:L49-58. [ Links ]

13. Sarian LO, Derchain SF, Naud P, Roteli-Martins C, Longatto-Filho A, Tatti S, et al. Evaluation of visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA), Lugol's iodine (VILI), cervical cytology and HPV testing as cervical screening tools in Latin America. This report refers to partial results from the LAMS (Latin AMerican Screening) study. J Med Screen 2005;12:142-149. [ Links ]

14. Murillo R, Luna J, Gamboa O, Osorio E, Bonilla J, Cendales R, et al. Cervical cancer screening with naked-eye visual inspection in Colombia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;109(3):230-234. [ Links ]

15. Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, Meijer CJ, Hoyer H, Ratnam S, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer 2006;119:1095-1101. [ Links ]

16. Murillo R, Piñeros M, Hernández G. Atlas de mortalidad por cáncer en Colombia. Bogotá: Instituto Nacional de Cancerologia/Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi, 2004. [ Links ]

17. Ministerio de Salud. Indicadores de cumplimiento en las intervenciones de protección específica y detección temprana. Resolución 3384 de 2000. Colombia: Ministerio de Salud, 2004. [ Links ]

18. Wiesner C, Tovar S, Piñeros M, Cendales R, Murillo R. Cervical cancer screening services offered in Colombia. Rev Colomb Cancerol 2009;13(3):134-144. [ Links ]

19. Cendales R, Wiesner C, Murillo RH, Piñeros M, Tovar S, Mejía JC. Quality of vaginal smears for cervical cancer screening: a concordance study. Biomedica 2010;30:107-115. [ Links ]

20. Piñeros M, Cendales R, Murillo R, Wiesner C, Tovar S. Pap test coverage and related factors in Colombia, 2005. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota) 2007;9:327-341. [ Links ]

21. Wiesner C, Cendales R, Murillo R, Piñeros M, Tovar S. Following-up females having an abnormal Pap smear in Colombia. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota) 2010;12:1-13. [ Links ]

22. Murillo R, Cendales R, Wiesner C, Piñeros M, Tovar S. Effectiveness of cytology-based cervical cancer screening in the Colombian health system. Biomedica 2009;29:354-361. [ Links ]

23. Ojeda G, Ordóñez M, Ochoa L, Samper B, Sánchez F. Salud sexual y reproductiva: Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud 2005. Bogotá: Profamilia, Bienestar Familiar, USAID, Ministerio de la Protección Social, 2005. [ Links ]

24. Adab P, McGhee SM, Yanova J, Wong CM, Hedley AJ. Effectiveness and efficiency of opportunistic cervical cancer screening: comparison with organized screening. Med Cares. 2004;42:600-609. [ Links ]

25. Arbyn M, Rebolj M, De Kok IM, Fender M, Becker N, O'Reilly M, et al. The challenges of organising cervical screening programmes in the 15 old member states of the European Union. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2671-2678. [ Links ]

26.Madlensky L, Goel V, Polzer J, Ashbury FD. Assessing the evidence for organised cancer screening programmes. Eur J Cancer 2003;39(12):1648-1653. [ Links ]

27. Spence AR, Goggin P, Franco EL. Process of care failures in invasive cervical cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 2007;45(2-3):93-106. [ Links ]

28. Denny L, Kuhn L, Hu CC, Tsai WY, Wright TC Jr. Human Papillomavirus-Based Cervical Cancer Prevention: Long-term Results of a Randomized Screening Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1–11. [ Links ]

29. Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, Jayant K, Muwonge R, Budukh AM, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1385-1394. [ Links ]

30. Public Helath Agency of Canada. Performance monitoring for cervical cancer screening in Canada. Report form the screening performance indictaors working group, Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Network (CCPCN). Canadá: Health Canada, 2009. [ Links ]

31. Lazcano-Ponce EC, Nájera-Aguilar P, Alonso de Ruiz Pa, Buiatti E, Hernández-Ávila M. Programa de Detección Oportuna de Cáncer Cervical en México. Diagnóstico situacional. Rev Inst Nal Cancerol Mex 1996; 42:123-140. [ Links ]

32. Ronco G, van Ballegooijen M, Becker N, Chil A, Fender M, Giubilato P, et al. Process performance of cervical screening programmes in Europe. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2659-2670. [ Links ]

33. Andrae B, Kemetli L, Sparén P, Silfverdal L, Strander B, Ryd W, et al. Screening-preventable cervical cancer risks: evidence from a nationwide audit in Sweden. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100(9):622-629. [ Links ]

Corresponding author:

Corresponding author:

Raúl Murillo.

Calle 73 No. 0-16 apto. 401.

Bogotá, Colombia.

E-mail: rmurillo@cancer.gov.co, raulhmurillo@yahoo.com

Received on: October 22, 2010

Accepted on: September 20, 2011