INTRODUCTION

Pharmacogenetics, a term coined in 1957 by Friedrich Vogel1, refers to the study of the genetics of variable drug response and is used interchangeably with pharmacogenomics (PGx), though the latter has a broader scope considering the impact of multiple variants across the genome. In this review, we will use the term PGx to refer to either concept2.

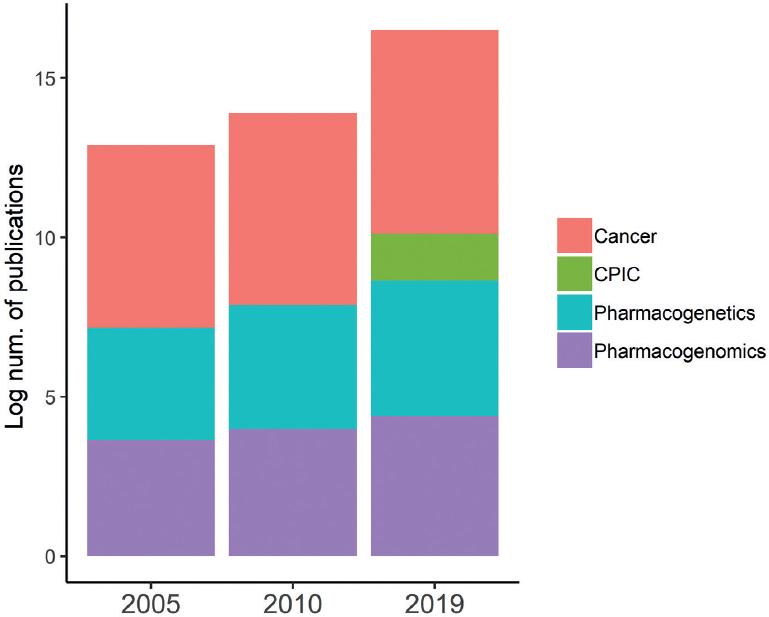

Initial observations on the relationship between drug efficacy and metabolic individuality dates back to the work of Motulsky and Garrod at the end of the 19th century3. The broader use of the terms pharmacogenetics in 1957 and PGx in 19974 supported the formality and the development of this discipline. Several decades of research in the field have led to the identification, characterization, validation, and implementation of dozens of genetic biomarkers to improve drug selection and efficacy and to prevent adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Up to June 2019, the scientific literature listed over 5500 articles on PGx, of which almost half were published in the past 5 years (Fig. 1). Recent studies cover different populations, although most efforts have focused on populations where technologies were more prevalent.

Figure 1 Growth of pharmacogenomics (PGx) published research overtime. Proportion of publications in PGx compared to those in cancer. The rate of growth of PGx reports overtime parallels that of cancer research. CPIC: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium.

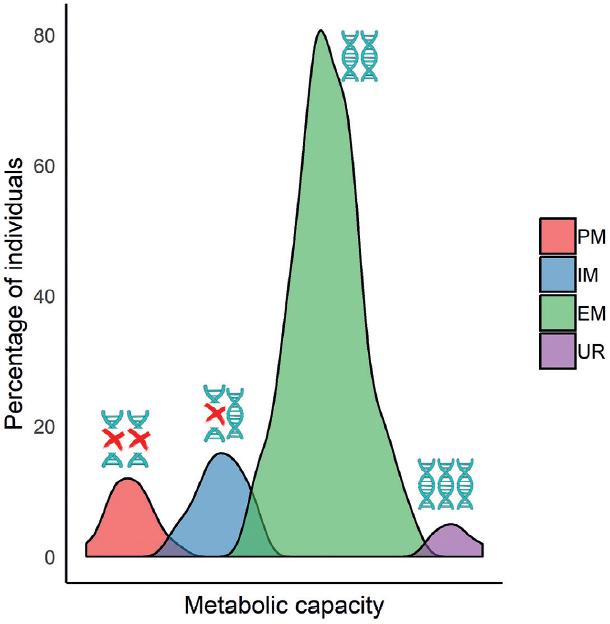

The advent of genomic technologies has facilitated the investigation of genes influencing drug safety and efficacy and its liaison with phenotyping assays. At present, it is possible to use pharmacogenetic information to personalize drug prescription for over 40 drugs using a varied arrange of genomic platforms, such as probe genotyping, microarrays, Sanger sequencing, and next-generation sequencing. These markers include single-nucleotide polymorphisms, copy-number variations, short insertions or deletions, and variable number tandem repeats, affecting a drugs pharmacodynamics (PD) or pharmacokinetics (PK). Genes affecting PK usually refer to enzymes involved in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, or elimination and include transporters and members of the CYP450 family (Table 1). Genes that affect a drugs target (PD) are intrinsic to the drug and can include enzymes, proteins, or receptors. For example, tamoxifen, used to treat breast cancer, binds to the estrogen receptor (ESR1) to prevent its activation. Furthermore, tamoxifen is a prodrug activated by CYP2D6; thus, CYP2D6 and ESR1 are part of tamoxifen pharmacogenetics (Table 1). Compared to PD, PK has been more intensely characterized so that it is possible to stratify patients into four phenotypes, poor, intermediate, extensive, or ultra-rapid phenotypes (Fig. 2)5.

Table 1 Most studied PGx genes classified by their main drug pathway

| Pharmacokinetics | Pharmacodynamics/ADRs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPYD | CES2 | SLC47A1 | RYR1 | GRK4 | DRD2 |

| ABCA1 | TPMT | CYP2C9 | EGFR | VDR | NPR1 |

| COMT | CYP3A4 | NAT2 | ESR1 | ACE | DRD1 |

| ABCG1 | CYP2B6 | ABCG2 | RYR2 | NR3C2 | PTGIS |

| UGT1A1 | POR | CYP1A2 | DBH | HSD11B2 | APOA1 |

| CYP2D6 | SLC22A1 | G6PD | PEAR1 | CRHR1 | ADRB2 |

| ABCB1 | CYP3A5 | MAOA | CACNA1S | ARID5B | VKORC1 |

PGx: pharmacogenomics; ADRs: adverse drug reactions.

Figure 2 Metabolism capacity (phenotypes) population distribution. Population distribution of variable metabolic activities (absorption, distribution, metabolism, or elimination). These differences give rise to four major genotypes.

As technology advances and results of the 1000 Genomes Project become available, research points toward the simultaneous use of hundreds of markers for tailoring diagnosis and treatment. Here, we will review actionable PGx markers, their classification, the process involved in the making of an actionable marker, institutions involved, and examples. Finally, we will complement this list with current knowledge of allele frequencies for Mexican populations and its potential impact for dosing or prescription.

DRUG-GENE PAIRS AND THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION (FDA)

Most pharmacogenetic markers are directly or indirectly involved in the PK, PD, or ADRs of medications connecting a gene and its variants with a pharmacological outcome, generating a drug-gene pair. For example, typical drug-gene pairs include warfarin, a widely used anticoagulant, and gene variants CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, CYP2C9*5, and VKORC1*2-4 represent part of the main picture of warfarins pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways. These, together with demographic characteristics, are capable of defining a tailored dose using PGx algorithms (e.g., warfarindosing.org)6. An example of a drug-gene pair related to ADRs is abacavir and HLA-B*5701. Patients with this HLA allele are strongly warned against the use of abacavir as they will likely present a lethal hypersensitivity reaction7 (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2 Current drug-gene pairs with CPIC guidelines for clinical implementation

| Year/Update | Gene | Drug(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 2011/2017 | CYP2C9, VKORC1, CYP4F2 | Warfarin |

| 2013/2017 | DPYD | Fluoropyrimidines |

| 2013/2017 | HLA-A, HLA-B | Carbamazepine, oxo-carbamazepine |

| 2013 | CYP2C19 | Clopidogrel |

| 2013 | IFNL3 | Peginterferon-alpha-based regimens |

| 2013/2018 | TPMT, NUDT15 | Thiopurines |

| 2014 | CYP2C9, HLA-B | Phenytoin |

| 2014 | CYP2D6 | Codeine |

| 2014 | G6PD | Rasburicase |

| 2014/2017 | CFTR | Ivacaftor |

| 2014 | HLA-B | Abacavir |

| 2014 | SLCO1B1 | Simvastatin |

| 2015 | CYP2D6, CYP2C19 | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| 2015 | CYP3A5 | Tacrolimus |

| 2015 | HLA-B | Allopurinol |

| 2015 | UGT1A1 | Atazanavir |

| 2016 | CYP2C19 | Voriconazole |

| 2016 | CYP2D6 | Ondansetron |

| 2016 | CYP2D6, CYP2C19 | Tricyclic antidepressants |

| 2018 | CYP2D6 | Tamoxifen |

| 2018 | RYR1, CACNAC1S | Volatile anesthetic agents |

| 2019 | CYP2B6 | Efavirenz |

| 2019 | CYP2D6 | Atomoxetine |

Adapted from https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines/.

The USA FDA, equivalent to most world drug regulatory agencies, has become an advocate for the use of PGx by including genetic information on drug labels promoting the understanding of how these markers contribute to drug responses8,9. Since 2014, the FDA has been increasingly approving personalized medicines, i.e., drugs for which PGx testing is necessary before prescription10. At present, there are 261 drug-gene pairs listed on the FDA website with pharmacogenetic information11 (/www.fda.gov/media/107901/download), but only a few require testing and have an official implementation guideline (Table 2). To be implemented, a clinically useful drug-gene pair requires a strong genotype-phenotype association followed by ample replication studies and validation.

To prioritize research and implementation policies, the classification of pharmacogenetic markers has been prompted by several researchers. For example, Haga and Burke classified PGx tests according to their biological foundation as acquired or inherited variants, alone or in combination, preemptive testing, and incidental or ancillary information13, but this classification did not stick to the current trends. Moreover, in its own classification effort, the FDA classifies PGx testing in (i) required, when genetic testing or functional protein assays ought be conducted before using the drug (e.g., trastuzumab HER2 and clopidogrel CYP2C19); (ii) recommended testing, highly useful to define dosing or preventing ADRs (e.g., azathioprine TPMT and citalopram CYP2D6); (iii) actionable, PGx information on dosing or toxicity due to genetic variants but does not mention genetic testing; and (iv) informative, mentions a gene or protein associated to the PK/PD of a drug but without variant-specific information. These tests are not FDA approved, but are regulated by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment of 198814. Of the 261 drug-gene pairs, 35% are for oncology, followed in proportion by antipsychotic, cardiovascular, metabolic, gastroenterology, hematology, urology, and autoimmune diseases. The most common PGx markers other than those for cancer treatment are located on genes CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and UGT1A1, influencing at least 20 different drugs.

Since genotyping and interpretation of results for 261 drug-gene pairs might not be straightforward, research groups have tried to consolidate shorter variant lists to facilitate PGx implementation. One of these attempts is part of the electronic Medical Records and Genomics network, which selected 82 pharmacogenes for preemptive sequencing in 5000 subjects. A selected list of these 82 genes is shown in Table 1 and represents a major part of the core of PGx15.

PHARMACOGENETIC GUIDELINES

The PGx knowledge base (PGKB) is an organization created over 18 years ago and is one of the largest resources of PGx data. Its website (www.pharmgkb.org) publishes PGx information, including drug-gene pairs, phenotypes, pathways, dosing guidelines, drug labels, and variant and clinical annotations, among other data. Note that, the concept of actionable marker is distinctively addressed by the FDA and the PGKB; the former usually refers to testing, while the PGKB refers to its clinical utility or actionability in practice16.

PGx markers listed by FDA come from two major platforms developed by the PGx Research Network which has under its wing, the PGKB, and the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC), the latter formed in 200917. The role of the PGKB is to collect, mine, annotate, curate, and assign a validation level to genetic markers of drug response according to the amount of clinical evidence associated to a drug trait. Their website currently lists genetic information for 309 drugs, although only markers with the highest level of validation have been medically endorsed and are included in implementation guidelines written and published by the CPIC18,19.

One step further to the advancement of PGx implementation is approached by the CPIC from which the FDA takes genetic information for drug labeling, warnings, and testing recommendations. Since CPICs goal is to develop and implement dosing guidelines, they also classify drug pairs according to their potential inclusion in a clinical setting as; A variants, with high evidence that should be used to change drug prescription; B variant, that could be used to improve prescription due to the availability of therapeutic alternatives; C variant, with some evidence but not yet convincing, impractical without clear drug alternatives; and D drug-gene variants, with few studies reported thus, unclear clinical actions. In brief, CPIC guidelines aim to guide patient care decisions for specific drugs utilizing genetic information20. At present, there are 23 published CPIC guidelines for 47 drugs, which include 19 genes also classified as VIP genes (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3 Allele frequencies for selected actionable PGx markers in major populations

| Gene variant | MAF (Natives) | MAF (Mestizo) | MAF (MXL/AMR) | MAF (EUR) | MAF (YRI) | MAF (EAS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C19*2 | 0-0.310 | 0 | 0.125 | 0.146 | 0.145 | 0.290 |

| rs4244285 | ||||||

| CYP2C19*3 | 0 | 0 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.083 |

| rs4986893 | ||||||

| CYP2D6*4 | 0.003-0.088 | 0.011 | 0.107 | 0.181 | 0.033 | 0.648 |

| rs3892097 | ||||||

| CYP2D6*5 | 0-0.036 | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.062 | 0.051 |

| gene deletion | ||||||

| CYP3A5*3 | NF | 0.730 | 0.800 | 0.920 | 0.150 | 0.710 |

| rs776746 | ||||||

| TPMT*3A | NF | 0.029-0.057 | 0.0384 | 0.0331 | 0.0045 | 0.0003 |

| rs1800460 | ||||||

| rs1142345 | ||||||

| UGT1A1*28 | NF | 0.334-0.360 | 0.400 | 0.316 | 0.391 | 0.148 |

| rs8175347 | ||||||

| VKORC1 | 0.008-0.020 | 0.050-0.190 | 0.460 | 0.410 | 0.100 | 0.880 |

| ars9923231 |

A comprehensive list of all CPIC variants and its allele frequency in Mexican populations is presented in Supplementary Table 1. MAF: minor allele frequency, NF: not found, 0 refers to an actual zero, MAF information comes from CPIC guidelines, the PGKB, HapMap 1000G or Genome Aggregation (gnomAD) databases, a full list with all level1 variants is found in Table S1. References to publications for each variant are also listed in Table S1.PGx: pharmacogenomics; MLA: Mexicans from Los Angeles.

EXAMPLES OF ACTIONABLE PGX MARKERS

The implementation of VKORC1, CYP4F2, and CYP2C9 markers for warfarin dosing was established in 2011 but has been rather controversial. Ample research has proven the strong association of variants on these genes and anticoagulant response or ADRs. Nevertheless, opposing results on the utility of PGx testing for warfarin by the USA21 and European22 studies were reported in 2013. Afterward, the CPIC published an update to this guideline suggesting the inclusion of continental ancestry for dose assessment23 and aiming for its implementation despite unsettling benefits.

Another interesting drug-gene pair is tamoxifen CYP2D6, for which a CPIC guideline was just published less than a year ago. Literature searches between 1982 and 2019 show almost 300 studies associating tamoxifen breast cancer response to genetic variation. Forty years of challenging research finally delivered a PGx guideline for clinical implementation. The barriers were many, including that tamoxifen is metabolized by dozens of enzymes but relies mostly on CYP2D6 to become activated. CYP2D6 is highly polymorphic with over 100 variants whose combinations can give rise to several metabolic phenotypes (Fig. 2)24. For example, individuals with the CYP2D6*9, *10, *14B, *17, *29, and *41 alleles will have decreased activity; individuals with the CYP2D6*3-*8, *11-*13, *15, *19-*21, *36, *38, *40, and *42 alleles will have no activity, and all of the above will elicit a lower activation of tamoxifen and decreased efficacy. CYP2D6 alleles have large differences between populations in addition to full deletions, duplications, and the presence of the pseudogene CYP2D7, which complicates assigning its functional impact25. At present, specific CYP2D6 genotype combinations are classified and ranked for different Activity Scores (AS = 0.5- ≥ 3) which are translated into a course of action for clinical application.

Clinical PGx guideline implementation has been slightly straightforward for several drug pairs. For instance, ivacaftor, prescribed for cystic fibrosis, is a targeted agent, approved only in cases showing specific genetic markers, including cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) G551D26. Therefore, ivacaftor prescription requires genetic testing. Nevertheless, new and rare variants on CFTR are continuously being reported, and a 2017 update for this guideline included about a dozen of additional CFTR polymorphisms to complement the PGx testing for ivacaftor. Another example is the activation of clopidogrel, which takes place by at least six enzymes. Hepatic CYP2C19 activity is mostly responsible for this activation, hence, poor CYP2C19 metabolizers are at high risk of cardiovascular events due to a lack of clopidogrel activity and should be given an alternative drug. CYP2C19 has over 30 reported alleles, and available genetic testing can identify the most common alleles, *2, *3, *4A/B, *5-*8, and *17, to provide with PGx guidance27. These examples are paralleled by many others24, supporting the prescription of personalized drugs with the aid of a PGx data network.

ETHNIC DIFFERENCES IN PGX

Variations in drug response between different populations have long been acknowledged. For example, CYP3A5*3, affecting tacrolimus disposition, is 2 times more frequent in Asian populations compared to Europeans, and variant CYP2D6*10, impacting at least 25% of all prescription drugs, is more common among individuals from Malaysia and China compared to other continental groups. Caucasian populations require a 30% lower dose of warfarin compared to Africans due to CYP2C9 and VKORC1 polymorphisms28-30. These variants account for 35% dose variations in Europeans, ~ 30% in Mexicans31, and 10% in African-Americans; . For the latter two, variants on NQO1, CALU, and GGCX may complement dose variation, highlighting the fact that certain genes distinctively impact on coumarin dosing according to population stratification. PGx research in Latin America has identified either similar frequencies on actionable markers among populations or striking differences. In this regard, variants on CYP3A5, VKORC1 rs9923231, CYP2C9, and SLCO1B1 show significant population differentiation (Fst) in admixed populations within Latin America compared to Europeans, Asians, or Africans29,30,32. Nevertheless, PGx differences are often 10- to 40-fold within individuals in any population, while differences between two ethnic groups are rarely > 2- or 3-fold33. Hence, interindividual variability is much greater than group variation, a fact framing PGx and all other complex traits so that an individualized treatment will consider interindividual variations above population differences29.

The notion that PGx would mostly benefit the outliers might have slowed down its implementation. Pharmacogenetic reports tend to list frequencies and statistics that may not necessarily highlight the relevance of a marker. For example, TPMT deficiency is a cause of severe ADRs in patients receiving thiopurines, which occurs in 1 of every 300 patients and the administration of anesthetics elicit malignant hyperthermia in 1 of every 2000 people due to variation in CACNA1S and RYR134. These statistics convey the idea of a low occurrence of PGx relevance. In this regard, the research groups of Ratain et al. and Roden et al. independently investigated actionable genotypes in over 10,000 patients and identified one or more actionable variants in > 90% of all individuals genotyped, emphasizing the benefits of the outlier in all of us and thus preemptive pharmacogenetic testing34.35.

STATUS OF ACTIONABLE PGX MARKERS IN MEXICANS

Population stratification for PGx relevant variants within Latin America has also been widely presented, for example, CYP3A5*3 and VKORC1 rs992323129, highlighting the identification and characterization of genetic variants that influence health, disease, and drug treatment as of paramount relevance for every single population37. In Mexico, Mexican Mestizos and Natives represent on average 80% and 10-15% of the population. Natives are categorized into 68 ethnic groups with low genetic diversity, but wide differentiation38. Novel variants, possibly private to Mexicans, have been described for CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and VKORC131,39-41 and could affect individual pharmacokinetic profiles and drug response. Nevertheless, Mexico does not have a program for PGx implementation. Recent updates to the federal or local health care laws (NOM 220-SSA, and the Hospital Pharmacy Program at ISSEMYM), mention PGx as a necessary tool for precision medicine, but no official policies have been issued from these initiatives, nor the adoption of those already published. Moreover, the identification of novel variants in individuals of Mexican descent is expected to increase as more genome and exome sequencing projects are completed. Today, we have an idea of this diversity given by the Exome Aggregation Consortium that reported over 600,000 genetic variants only in Mexican and Latin American individuals20. We sought to identify allele frequencies of the 144 variants in 19 genes of current CPIC guidelines in Mestizos other than MXL (Mexicans from Los Angeles) and in Natives. Table 3 summarizes allele frequencies of selected variants. A full list with all 144 variants is presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Interestingly, 12.5% (18) of all CPIC listed variants were not found in any population from Mexico. These were on CFTR and RYR1, 144 PGx markers have been listed for these genes, but no allele frequency (AF) information was found for Natives or Mestizos. (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 1).

Table 3 and Supplemental Table S1 summarize information on a higher AF of variants on VKORC1, CYP2D6*4, CYP2C9*3, or SLCO1B1*5 in Caucasians versus Mestizos or Natives, in contrast to higher AF in Natives/Mestizos versus Caucasians, for CYP3A5*1,*7, CYP2B6*4, HLA-B*1502, and HLA-B*5801. Moreover, variants CYP2C19*2/*3, CFTR G178R, S1251N, and TPMT*4 seem to be absent in Mexicans (Table 3 and Table S1). Similarities in AF have been reported for CYP2B6*1/*6, CYP3A5*3/6, TPMT*1/*3A, and UGT1A1*28, assuming similar PK/PD and ADRs as those observed for other populations. Nevertheless, these comparisons must be taken with caution as many determinations in Mexicans have been performed with a small sample size. Strikingly, fewer than 25% of the 144 PGx implemented variants were available for one or several native populations (Table S1). A scarce availability on AF data hinders comparisons between groups or populations, but prompts to direct endeavors to intensify PGx data collection in these individuals. As an example, we present AF in variants retrieved for Zapotecos, Native dwellers of the South and Center South of the country, to pinpoint similarities and differences when compared to Mestizos. Apparent differences were observed on HLA-B5801, CYP2C9*3, and SLCO1B1*5 (Table 4). It is expected that such comparisons are due to change as more research gathers information from natives.

Table 4 Example of MAF differences in Natives (Zapotecos) and Mestizos

| PGx marker | MAF Zapotecos* | MAF Mestizos |

|---|---|---|

| HLA-A*31:01 | 0.067 | 0.024 0.083 (5) |

| HLA-B*57:01 | 0 | 0 0.015 (6) |

| HLA-B*15:02 | 0 | 0 0.009 (7) |

| HLA-B*58:01 | 0.022 | 0 0.100 (5) |

| CYP2C9*2 rs1799853 | 0 | 0.130 |

| CYP2C9*3 rs1057910 | 0.012 | 0.130 |

| SLCO1B1*5 rs4149056 | 0.044 | 0.109 0.153 |

| UGT1A1*80 rs887829 | 0.367 | 0.346 |

| TPMT*2 rs1800462 | 0 | 0 0.0375 |

| TPMT*3B rs1800460 | 0.056 | 0.003 0.041 |

| TPMT*3C rs1142345 | 0.056 | 0.006 0.045 |

| TPMT*4 rs1800584 | 0 | 0 |

*The Zapotecos population size is close to 1 million. Many migration waves have pinpointed significant Zapoteco dwellings in several cities in California, USA.PGx: pharmacogenomics.

CONCLUSIONS

PGx plays a major role in precision medicine. Short-term endeavors may seek to complete a catalog of PGx variation worldwide to aid clinicians in the assignment of treatments with a higher success rate, according to the patients genetic makeup. More likely, long-term efforts will dissect the whole human genome individually in a pre-emptive manner, in addition to the consideration of relevant factors such as the environment and the microbiome42.

The implementation of PGx in Latin Americas admixed populations faces common difficulties, including access to technology, trained personnel, marker interpretation, and its inclusion in daily practice. Local implementation is also hindered by population stratification and a lack of complete registries of inhabitants PGx variations and health-care records. A dweller of Mexico can show a Native/Caucasian ancestral component from 0.01 to 0.99 hampering the use of ancestry as a PGx proxy. Moreover, understudied populations may hold private variants not previously reported nor assessed for functional impact.

We envision the use of actionable variants listed by international curating institutions such as the PGKB and the CPIC, complemented with private and rare variants using sequencing strategies on local populations.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)