INTRODUCTION

In late 2019, a cluster of patients with pneumonia of unknown etiology was detected in Wuhan, Hubei, China. By January 2020, a new coronavirus (Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus [SARS-CoV-2]) was identified as the causative agent. The World Health Organization (WHO) designated this new entity as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)1,2. After the first cases were reported, COVID-19 rapidly spread all over the world; on the 11th of March, the WHO declared this novel disease a global pandemic2. In Mexico, the first imported cases were described on February 28, 2020, and by the 24th of March, local transmission was detected3. As of April 24, 2020, SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in 2,626,321 subjects and caused over 181,938 deaths globally (12,872 cases and 1221 deaths in our country)2,4.

Several studies have described the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection5-9. The clinical spectrum of COVID-19 ranges from a self-limited upper respiratory tract illness to severe pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome, among other severe manifestations (e.g., acute kidney injury and multi-organ failure)1,5,10. Regional information regarding the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with COVID-19 is needed for a better understanding of the disease. Here, we aimed to describe the clinical and epidemiological features of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosed in a tertiary-care center in Mexico City and to assess main differences according to treatment setting (ambulatory vs. hospital) or by the need of intensive care (IC).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design, setting, and participants

We conducted a prospective cohort study in a tertiary care center located in Mexico City, a 211-bed referral hospital for adults that were converted as a referral center for COVID-19 on March 16, 2020. Preparations for the current pandemic included training of all personnel and changes in hospital infrastructure and organization (i.e., a new triage section and an increase in the IC unit [ICU] capacity from 14 to 40 beds). The general wards distribution and patients flow were redesigned as well. All patients with the requirement of IC were exclusively treated in ICU areas. All consecutive subjects with COVID-19 diagnosed between February 26, 2020s and April 11, 2020, were included using the definitions described by the WHO11. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (ref. no. 3333). Written informed consent was waived because of the observational nature of the study.

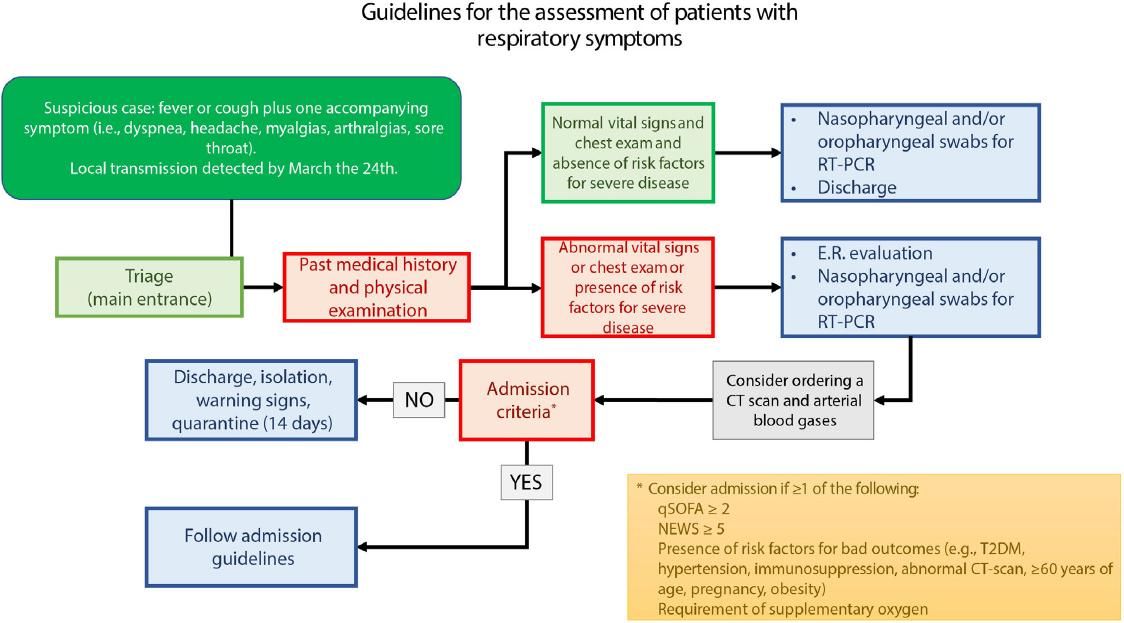

From February 26 to March 23, SARS-CoV-2 infection testing was performed in suspected cases defined as fever or cough plus one extra symptom (i.e., dyspnea, headache, myalgias, arthralgias, and sore throat) in patients with a history of contact with a COVID-19 case or of a recent travel to countries with local transmission. Since March 24, all suspected cases were tested for COVID-19 regardless of history of previous travels. The need for admission was determined by treating physicians according to our institutional guidelines (Supplementary Fig. 1). Inpatients were followed until discharge or death (last status update was on April 11, 2020); ambulatory patients were evaluated once.

Molecular diagnostic procedures

SARS-CoV-2 testing was carried out on naso/oropharyngeal swabs (two or more samples per patient, with at least one nasopharyngeal swab). Only one patient required a tracheal aspirate for diagnosis. Upper-respiratory samples were transported in a universal transport medium for viruses. Nucleic acid extraction was performed using the NucliSens easyMAG system® (bioMérieux, Boxtel, The Netherlands). Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction was carried out on an Applied Biosystems 7500 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using primers and conditions described elsewhere12. The cycle threshold value (Ct-value) for positivity was 38.

Data collection and outcomes

Clinical and epidemiological data were extracted at first evaluation using a standardized case report form13; the remainder information was obtained from electronic clinical records. Diabetes was defined as either type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Imaging and laboratory studies were performed accordingly to our local recommendations. In brief, suggested basal laboratory assessment included complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, inflammatory markers (i.e., C-reactive protein, ferritin, procalcitonin), creatine kinase, fibrinogen, D-dimer, and lactate dehydrogenase (normal ranges are provided in the Supplementary Table 1). A computerized tomography (CT) scan was performed in all hospitalized patients before admission. The quick Sequential (Sepsis-related) Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score, the National Early Warning Score (NEWS), the MuLBSTA score for viral pneumonia mortality, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index score were calculated for inpatients if data were available14-17. The primary outcomes were mechanical ventilation, ICU admission, all-cause mortality, and length of stay.

Supplementary Table 1 Reference values for laboratory tests in the INCMNSZ

| Test | Units | Reference valuesa |

|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count | × 109/L | 4-12 |

| Neutrophils | × 109/L | 1.7-7 |

| Lymphocytes | × 109/L | 0.9-2.9 |

| Monocytes | × 109/L | 0.3-0.9 |

| Hemoglobin | g/dL | 14.5-17.7 |

| Hematocrit | % | 42.5-52.5 |

| Platelets | × 109/ul | 150-450 |

| Creatinine | mg/dl | 0.7-1.3 |

| Blood urea nitrogen | mg/dl | 7-25 |

| Sodium | mmol/L | 136-146 |

| Potassium | mmol/L | 3.5-4.01 |

| Alanine aminotransferase | U/L | 7-52 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | U/L | 13-39 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | U/L | 34-104 |

| Total bilirubin | mg/dL | 0.3-1 |

| Albumin | g/dL | 3.5-5.7 |

| Globulin | g/dL | 1.9-3.7 |

| C-reactive protein | mg/dL | 0-1 |

| Ferritin | ng/mL | 23-336.2 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | mm/h | 2-30 |

| Procalcitonin | ng/mL | 0-0.5 |

| pH | 7.35-7.45 | |

| Fraction of inspired oxygen | % | 21% without supplementary oxygen |

| Partial pressure of oxygen | mmHg | 80-100 |

| Partial pressure of carbon dioxide00 | mmHg | 35-45 |

| Bicarbonate | mmol/L101 | 22.2-28.3 |

| Lactate | mmol/L | 0.6-1.6 |

| Fibrinogen | mg/dl | 238-498 |

| D dimer | ng/mL FEU | 0-500 |

| Creatine phosphokinase | U/L | 30-223 |

| High-sensitive troponin I | pg/mL | 0-20 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | U/L | 140-271 |

aReference values at the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán (INCMNSZ).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and proportions. Continuous variables were described using mean, median, standard deviation, and interquartile range (IQR) values as required. Differences between study groups were assessed using the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t-test, or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. To identify significant laboratory features that appeared during disease progression, we compared the dynamic profile in eight laboratory tests among inpatients according to their need of IC using generalized linear mixed models adjusted by age and sex. For this analysis, we included only patients with at least two laboratory measures. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the analyses were performed using R software, version 3.6.3.

RESULTS

Demographic and presenting characteristics

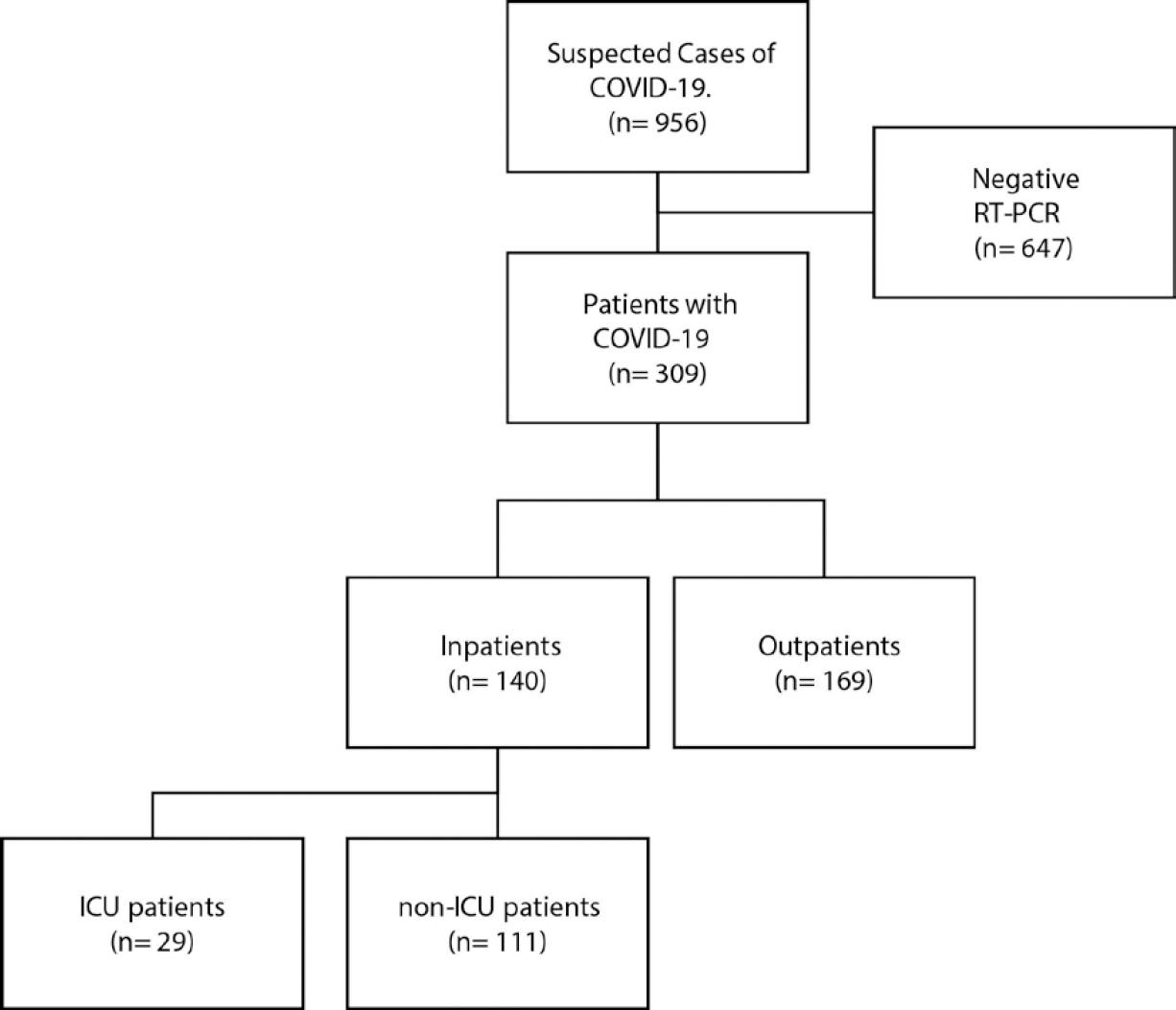

We included 309 subjects, 140 inpatients, and 169 outpatients (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The median age was 43 years (range, 11-92), 59.2% were men, and 18.6% were healthcare workers (12.3% of them worked at our center). The median body mass index (BMI) was 29.00 kg/m2; 39.6% were overweight, and 39.6% had obesity. The median time from initiation of symptoms to hospital evaluation was 5 days (range, 0-24). The most common symptoms were cough (85.6%), headache (80.7%), fever (79.4%), general malaise (77.1%), and myalgias (72.8%). Anosmia, dysgeusia, and dermatological manifestations were not systematically evaluated; they were observed in 22 of 27 (81.5%), 6 of 9 (66.7%), and 2 of 22 (9.1%) patients, respectively.

Table 1 Comparison of baseline and presenting characteristics between inpatients and outpatients with COVID-19 evaluated at the INCMNSZ (February 26, 2020-April 11, 2020)

| Characteristics | No. (%) Total (n = 309) | Inpatients (n = 140) | Outpatients (n = 169) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 43.00 (33.00, 54.00) | 49.00 (39.00, 61.25) | 39.00 (30.00, 49.00) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, male | 183 (59.2) | 85 (60.7) | 98 (58.0) | 0.712 |

| Healthcare worker | 57 (18.6) | 16 (11.4) | 41 (24.7) | 0.005 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| CCI, median (IQR) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.00, 2.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 41 (13.3) | 32 (22.9) | 9 (5.3) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 61 (19.7) | 45 (32.1) | 16 (9.5) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 9 (2.9) | 6 (4.3) | 3 (1.8) | 0.309* |

| Obesity | 67 (39.6) | 50 (39.7) | 17 (39.5) | 0.999 |

| Overweight | 67 (39.6) | 52 (41.3) | 15 (34.9) | 0.576 |

| COPD | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0.592* |

| Asthma | 9 (2.9) | 2 (1.4) | 7 (4.1) | 0.191* |

| Immunosuppression | 18 (5.8) | 8 (5.7) | 10 (5.9) | 0.999* |

| Chronic liver disease | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0.592* |

| Smoker (current or former) | 47 (15.2) | 25 (17.9) | 22 (13.0) | 0.264 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Days from symptoms onset to hospital admission, median (IQR) | 5.00 (2.00, 8.00) | 7.00 (4.00, 9.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 7.00) | < 0.001 |

| Fever | 243 (79.4) | 131 (93.6) | 112 (67.5) | < 0.001 |

| Cough | 262 (85.6) | 128 (91.4) | 134 (80.7) | 0.013 |

| Chest pain | 117 (38.2) | 53 (37.9) | 64 (38.6) | 0.994 |

| Dyspnea | 124 (40.5) | 88 (62.9) | 36 (21.7) | < 0.001 |

| Headache | 246 (80.7) | 107 (77.0) | 139 (83.7) | 0.18 |

| Irritability | 84 (27.9) | 34 (25.2) | 50 (30.1) | 0.412 |

| Diarrhea | 94 (30.7) | 48 (34.3) | 46 (27.7) | 0.264 |

| Vomiting | 30 (9.8) | 18 (12.9) | 12 (7.2) | 0.145 |

| Shaking chills | 182 (59.7) | 85 (61.2) | 97 (58.4) | 0.715 |

| Abdominal pain | 39 (12.7) | 16 (11.4) | 23 (13.9) | 0.644 |

| Myalgia | 222 (72.8) | 106 (76.3) | 116 (69.9) | 0.264 |

| Arthralgia | 199 (65.2) | 95 (68.3) | 104 (62.7) | 0.358 |

| Malaise | 236 (77.1) | 118 (84.3) | 118 (71.1) | 0.009 |

| Rhinorrhea | 126 (41.2) | 44 (31.4) | 82 (49.4) | 0.002 |

| Sore throat | 161 (52.8) | 65 (46.8) | 96 (57.8) | 0.07 |

| Conjunctivitis | 73 (23.9) | 25 (17.9) | 48 (28.9) | 0.033 |

| Anosmia | 22 (81.5) | 9 (64.3) | 13 (100.0) | 0.041* |

| Dysgeusia | 6 (66.7) | 5 (62.5) | 1 (100.0) | 0.999 |

| Dermatosis | 2 (9.1) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (–) | 0.999* |

| Physical examination | ||||

| Weight, median (IQR), Kg | 78.00 (69.00, 88.00) | 78.00 (70.00, 88.00) | 76.00 (68.50, 89.50) | 0.624 |

| Height, mean (SD), meters | 1.65 (0.10) | 1.65 (0.10) | 1.66 (0.09) | 0.524† |

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 29.00 (25.60, 31.24) | 29.10 (25.60, 31.22) | 27.60 (25.10, 31.61) | 0.309 |

| Temperature, median (IQR), °C | 37.00 (36.50, 37.82) | 37.20 (36.50, 38.00) | 36.70 (36.20, 37.50) | 0.002 |

| Heart rate, mean (SD), bpm | 97.45 (17.54) | 101.39 (18.26) | 91.38 (14.48) | < 0.001† |

| Respiratory rate, median (IQR), rpm | 20.00 (18.00, 24.00) | 22.00 (20.00, 25.00) | 19.00 (17.00, 21.00) | < 0.001 |

| Oxygen saturation**, median (IQR), % | 92.00 (88.00, 94.00) | 89.00 (86.00, 92.00) | 94.00 (93.00, 96.00) | < 0.001 |

| Arterial pressure, median (IQR): | ||||

| Systolic, mmHg | 122.00 (112.00, 134.00) | 120.00 (110.75, 134.25) | 125.00 (117.00, 133.00) | 0.155 |

| Diastolic, mmHg | 78.00 (70.00, 85.50) | 75.00 (67.00, 81.00) | 80.00 (70.00, 90.00) | 0.002 |

| Mean, mmHg | 92.33 (83.67, 100.33) | 90.50 (83.33, 99.00) | 94.67 (86.67, 104.33) | 0.006 |

BMI: body mass index; bpm: beats per minute; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease;

INCMNSZ: Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán; IQR: interquartile range; rpm: breaths per minute.

*Fisher’s exact test; †Unpaired student t-test.

**FiO2 (fraction of inspired oxygen) 21%.

Comparison between in- and outpatients

In comparison to outpatients, inpatients were older (median age 49 vs. 39 years) and had more comorbidities (diabetes 22.9% vs. 5.3%; hypertension 32.1% vs. 9.5%; and Charlson Comorbidity Index median 1 vs. 0), Table 1. Furthermore, inpatients presented with fever (93.6% vs. 67.5%), cough (91.4% vs. 80.7%), dyspnea (62.9% vs. 21.7%), and malaise (84.3% vs. 71.1%), more often, and less frequently with rhinorrhea (31.4% vs. 49.4%), conjunctivitis (17.9% vs. 28.9%), and anosmia (64.3% vs. 100%). On physical examination, hospitalized patients had a lower capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2, median 89% vs. 94%), mean arterial pressure (MAP, median 90.5 vs. 94.67 mmHg), a higher heart rate (HR, mean 101.39 vs. 91.38 bpm), and respiratory rate (RR, median 22 vs. 19 rpm).

Comparison of inpatients according to their need for IC

All inpatients had a chest CT-scan compatible with pneumonia. Among these patients, 29 (20.7%) were admitted to intensive-care areas, mostly due to respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation (28 [96.7%]). The median time from symptoms onset to ICU transfer was 11 days (range, 4-36) and the time from hospital admission to ICU transfer 2 days (range, 0-31) (Table 3). We found a higher frequency of diabetes (41.4% vs. 18%) in ICU patients; the remaining basal characteristics were similar between groups (Table 2). Since admission, ICU patients referred abdominal (24.1% vs. 8.1%), and chest pain more frequently (55.2% vs. 33.3%) The latter did not reach statistical significance. On baseline physical examination, ICU patients had a higher BMI (BMI, median 30.5 vs. 28.57), a higher RR (median 26 vs. 22), and a lower SpO2 (median 83.5 vs. 89). The qSOFA score (median 1.00 [IQR; 1.00, 1.00] vs. 1.00 [IQR; 0.00, 1.00]), MuLBSTA score (median 9 vs. 8), and NEWS score (median 8 vs. 6) were higher at presentation among ICU patients when compared to non-ICU patients (Table 3). As shown in this Table, several differences regarding baseline laboratory exams also were observed.

Table 2 Comparison of baseline and presenting characteristics of inpatients with COVID-19 according to their requirement of intensive care at the INCMNSZ (February 26, 2020-April 11, 2020)

| Characteristics | No. (%) ICU (n = 29) | non-ICU (n = 111) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 53.00 (40.00, 64.00) | 48.00 (39.00, 60.50) | 0.271 |

| Sex, female | 9 (31.0) | 46 (41.4) | 0.419 |

| Healthcare worker | 4 (13.8) | 12 (10.8) | 0.743* |

| Comorbidities | |||

| CCI, median (IQR) | 1.00 (0.00, 3.00) | 1.00 (0.00, 2.00) | 0.066 |

| Diabetes | 12 (41.4) | 20 (18.0) | 0.016 |

| Hypertension | 10 (34.5) | 35 (31.5) | 0.936 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1 (3.4) | 5 (4.5) | 0.999* |

| Obesity | 15 (51.7) | 35 (36.1) | 0.196 |

| Overweight | 10 (34.5) | 42 (43.3) | 0.528 |

| COPD | 1 (3.4) | 1 (0.9) | 0.373* |

| Asthma | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.8) | 0.999* |

| Immunosuppression | 3 (10.3) | 5 (4.5) | 0.362* |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 (3.4) | 1 (0.9) | 0.373* |

| Smoker (current or former) | 7 (24.1) | 18 (16.2) | 0.536* |

| Symptoms | |||

| Days since symptoms onset to hospital admission, median (IQR) | 8.00 (6.00, 12.00) | 7.00 (4.50, 9.00) | 0.21 |

| Fever | 28 (96.6) | 103 (92.8) | 0.685* |

| Cough | 28 (96.6) | 100 (90.1) | 0.46* |

| Chest pain | 16 (55.2) | 37 (33.3) | 0.052 |

| Dyspnea | 22 (75.9) | 66 (59.5) | 0.158 |

| Headache | 18 (62.1) | 89 (80.9) | 0.058 |

| Irritability | 9 (33.3) | 25 (23.1) | 0.399 |

| Diarrhea | 11 (37.9) | 37 (33.3) | 0.807 |

| Vomiting | 7 (24.1) | 11 (9.9) | 0.059* |

| Shaking chills | 17 (58.6) | 68 (61.8) | 0.92 |

| Abdominal pain | 7 (24.1) | 9 (8.1) | 0.024* |

| Myalgia | 23 (79.3) | 83 (75.5) | 0.85 |

| Arthralgia | 21 (72.4) | 74 (67.3) | 0.76 |

| Malaise | 22 (75.9) | 96 (86.5) | 0.266 |

| Rhinorrhea | 6 (20.7) | 38 (34.2) | 0.24 |

| Sore throat | 17 (58.6) | 48 (43.6) | 0.219 |

| Conjunctivitis | 6 (20.7) | 19 (17.1) | 0.861 |

| Anosmia | 0 (0.0) | 9 (75.0) | 0.11* |

| Dysgeusia | 0 (0.0) | 5 (83.3) | 0.206 |

| Dermatosis | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | 0.94 |

| Physical examination | |||

| Weight, median (IQR), Kg | 80.00 (70.00, 90.00) | 78.00 (69.00, 87.00) | 0.185 |

| Height, mean (SD), meters | 1.65 (1.60, 1.70) | 1.65 (1.58, 1.72) | 0.765 |

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 30.50 (27.04, 33.87) | 28.57 (25.50, 31.20) | 0.037 |

| Body temperature, median (IQR), °C | 37.30 (36.78, 37.95) | 37.20 (36.50, 38.00) | 0.382 |

| Heart rate, median (IQR), bpm | 109.00 (94.00, 120.00) | 101.00 (86.50, 114.00) | 0.068 |

| Respiratory rate, median (IQR), rpm | 26.00 (22.00, 30.00) | 22.00 (19.50, 24.00) | < 0.001 |

| Oxygen saturation (FiO2 21%), median (IQR), % | 83.50 (76.00, 88.00) | 89.00 (87.00, 92.00) | < 0.001 |

| Arterial pressure, median (IQR) | |||

| Systolic, mmHg | 124.00 (110.00, 137.00) | 120.00 (112.00, 133.00) | 0.857 |

| Diastolic, mmHg | 74.00 (62.00, 82.00) | 76.00 (68.50, 81.00) | 0.877 |

| Mean, mmHg | 90.00 (83.33, 97.33) | 91.00 (83.33, 100.00) | 0.811 |

BMI: body mass index; bpm: beats per minute; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease;

FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; INCMNSZ: Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán; IQR: interquartile range; rpm: breaths per minute.

*Fisher’s exact test.

Table 3 Baseline prognostic scores and laboratory findings of inpatients with COVID-19 according to their requirement of intensive care at the INCMNSZ (February 26, 2020-April 11, 2020)

| Baseline prognostic scores | Median (IQR) | non-ICU (n = 111) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU (n = 29) | |||

| qSOFA | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.021 |

| NEWS | 8.00 (7.00, 10.00) | 6.00 (4.00, 8.00) | < 0.001 |

| MuLBSTA | 9.00 (8.00, 12.00) | 8.00 (5.00, 9.00) | 0.006 |

| High risk MuLBSTA | 101 (91%) | 21 (72%) | 0.013 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Complete blood count | |||

| White blood cell count, × 109/L | 8.1 (5.5, 11.2) | 6.0 (4.6, 8.05) | 0.002 |

| Neutrophil count, × 109/L | 7.2 (4.3, 9.4) | 4.4 (3.1, 6.3) | 0.001 |

| Lymphocyte count, × 109/L | 0.68 (0.5, 1.1) | 0.88 (0.62, 1.1) | 0.185 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 15.50 (14.00, 16.60) | 15.60 (14.00, 16.95) | 0.422 |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | 213.00 (175.00, 283.00) | 193.00 (161.00, 231.00) | 0.034 |

| Basic metabolic panel | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.90 (0.74, 1.09) | 0.90 (0.70, 1.10) | 0.559 |

| Blood Urea Nitrogen, mg/dL | 15.40 (10.90, 16.70) | 12.30 (10.20, 16.10) | 0.067 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 136.00 (133.00, 138.00) | 136.00 (133.00, 138.00) | 0.741 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 4.00 (3.66, 4.06) | 4.02 (3.76, 4.30) | 0.107 |

| Liver function tests | |||

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 42.00 (26.00, 53.00) | 34.00 (22.90, 55.05) | 0.349 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 56.00 (34.00, 68.00) | 34.00 (25.00, 51.50) | 0.004 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 90.00 (63.00, 112.00) | 82.00 (64.50, 99.50) | 0.299 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.59 (0.49, 0.73) | 0.50 (0.41, 0.66) | 0.118 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.30 (3.13, 3.80) | 4.00 (3.72, 4.20) | < 0.001 |

| Globulin, g/dL | 3.34 (2.93, 3.51) | 3.10 (2.83, 3.27) | 0.047 |

| Acute-phase reactants | |||

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | 13.74 (11.02, 18.98) | 6.50 (2.39, 12.91) | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 646.50 (311.82, 891.25) | 335.00 (203.00, 603.00) | 0.008 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/h | 34.00 (24.00, 37.50) | 19.00 (10.25, 26.00) | 0.127 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 0.56 (0.48, 0.80) | 0.05 (0.05, 0.11) | < 0.001 |

| Arterial blood gases | |||

| pH | 7.46 (7.43, 7.48) | 7.45 (7.42, 7.48) | 0.616 |

| PaO2, mmHg | 63.90 (55.95, 93.50) | 59.00 (54.00, 68.00) | 0.171 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 31.00 (28.50, 35.35) | 32.00 (29.20, 34.00) | 0.737 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 195.00 (99.83, 252.50) | 271.43 (245.71, 302.67) | < 0.001 |

| HCO3, mmol/L | 22.00 (19.10, 24.00) | 21.80 (20.60, 22.70) | 0.47 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 1.15 (1.00, 1.45) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.30) | 0.18 |

| Others | |||

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 684.00 (485.00, 771.25) | 491.00 (415.00, 665.25) | 0.008 |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 729.00 (527.00, 1328.72) | 454.00 (353.00, 723.50) | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine phosphokinase, U/L | 126.00 (68.25, 272.00) | 104.50 (57.00, 245.25) | 0.593 |

| High-sensitivity troponin I, pg/mL | 10.60 (5.62, 16.52) | 4.00 (2.80, 5.50) | < 0.001 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 488.00 (325.00, 577.00) | 266.50 (218.75, 351.75) | < 0.001 |

FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; ICU: intensive care unit; INCMNSZ: Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán;

IQR: interquartile range; NEWS: National Early Warning Score; MulBSTA: Multilobular infiltration, hypo-lymphocytosis, bacterial coinfection, smoking history, hypertension and age score; NIH: National Institute of Health; qSOFA: quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

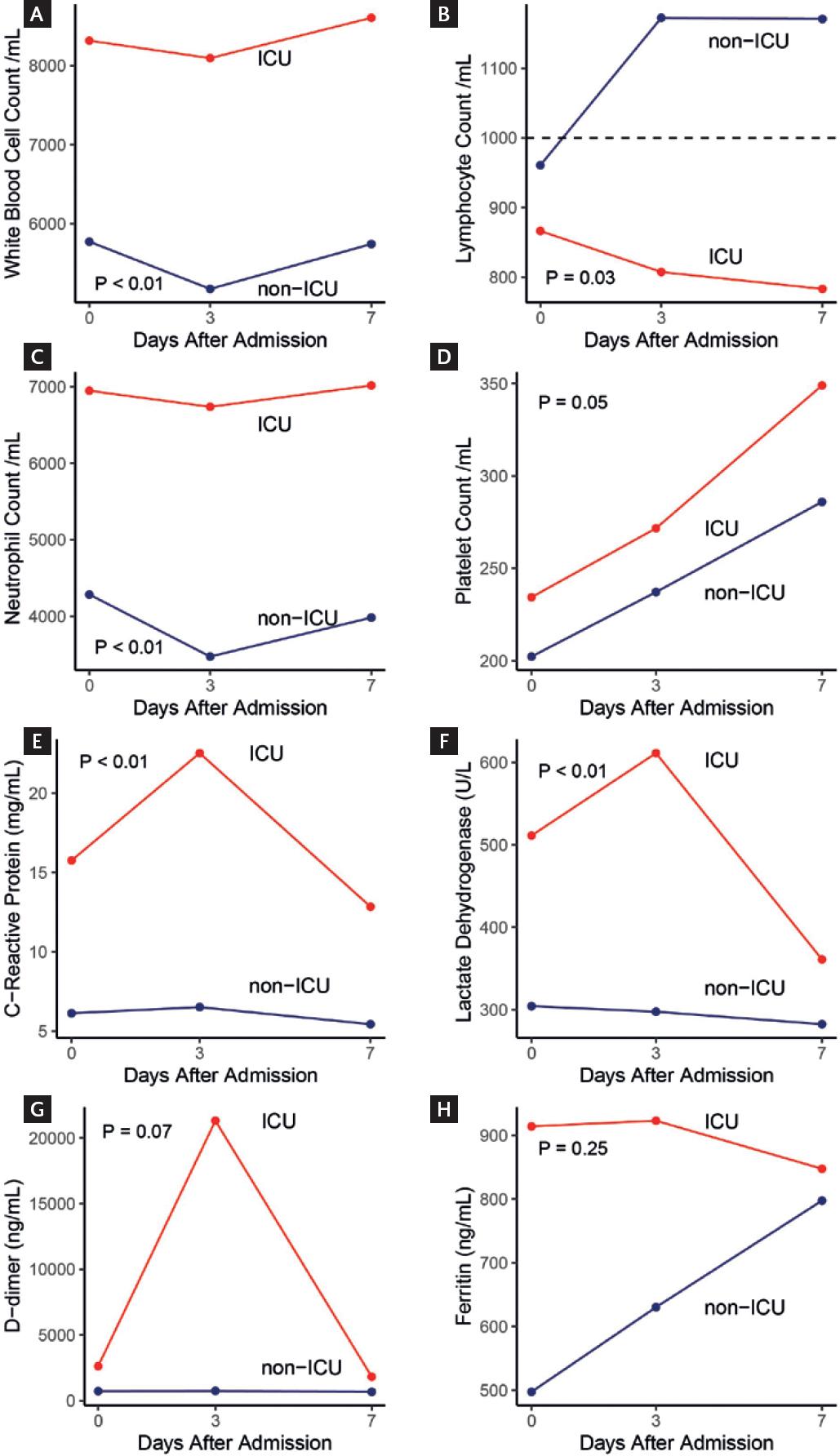

The dynamic profile of some laboratory tests involved in inflammation was also different. Patients who required ICU had lower lymphocyte counts (p = 0.03) and higher WBC and neutrophil counts over time (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2). Moreover, the levels of C-reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase were significantly higher over time in patients who were admitted to the ICU than in those who were not (p < 0.01). Platelet counts, levels of D-dimer, and ferritin were also higher in patients who were admitted to the ICU; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Treatment and outcomes

By April 11, the median length of stay of all inpatients was 5 days (IQR, 3-7.75), 6 days (IQR, 3-14) for ICU patients, and 4 days (IQR, 2-7) for non-ICU patients. All inpatients received empiric antibiotic treatment (the length of therapy was not analyzed for the present report). A beta-lactam (i.e., amoxicillin-clavulanate, ceftriaxone, or piperacillin-tazobactam) was administered to 137 (98%) patients and a macrolide (i.e., azithromycin or clarithromycin) to all of them. Moreover, oseltamivir was added in 104 (74.3%) inpatients. At least one antiviral or immunomodulatory therapy currently under evaluation for COVID-19 was administered to 106 patients (76%) (i.e., chloroquine [n = 44], hydroxychloroquine [n = 54], tocilizumab [n = 20], and/or remdesivir vs. placebo [n = 5]). Anticoagulation (either prophylactic or therapeutic) was given to 127 (90.7%) subjects. By the time of the last status update (April 11, 2020), 65 (46.4%) inpatients were discharged because of improvement, 70 (50%) continued hospitalized, and 5 (3.6%) had died (5/70 [7.1%] among discharged patients). Median age at death was 45 years (range, 33-67); septic shock and severe ARDS were stated as their cause of death.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we described the experience of a tertiary care center in Mexico City recently converted to a referral center for COVID-19. Our results provide a comprehensive description of the clinical and epidemiological features of the first wave of patients diagnosed with COVID-19. We were able to identify several clinical, epidemiological, and laboratory differences between patients according to their treatment setting (ambulatory vs. hospital) or by their need of IC. These findings could be useful for clinicians during hospitalization decision-making and in predicting the need of IC.

Overall, patients were mostly middle-aged obese or overweight men who came into the emergency room within 1 week of symptoms onset. Most COVID-19 cohort studies have focused on hospitalized subjects with several features that are shared by ours, such as presenting symptoms (mainly fever and/or acute respiratory symptoms) and a predominance of male sex1,8,18,19.

Interestingly, while the median age of our patients was similar to the reported in some series from China (median, 47-56 years), our population was younger than those from other cohorts (e.g., the United States of America, median 63 years)1,8,19, even after analyzing out- and inpatients, and the need for IC. Age is a well-known factor that impacts negatively on the outcome in COVID-19 infection and other infections, presumably due to immunosenescence20. The predominance of middle-aged subjects in our population (even those that require IC), contrasts with the findings from other reports1,19,21. These findings could be explained in part by the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in our cohort. Kass et al. found a significant inverse correlation between age and BMI among COVID-19 patients (i.e., younger inpatients were more likely to be obese). Likewise, Lighter et al. reported an odds ratio for requiring IC of 1.8 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2-2.7) and 3.6 (CI, 2.5-5.3) in patients < 60 years with a BMI between 30 and 34 or equal or > 35, respectively22,23. This assumption is also supported by our finding that a higher BMI was more frequently found among our inpatient population, as well as in patients who required IC.

Several underlying mechanisms possibly explain the relationship between obesity and COVID-19 severity. These could be mechanical in nature (e.g., restrictive lung ventilatory defect), pro-inflammatory or immune dysregulatory, or even related to a higher prevalence of other comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension among obese patients22. The association between BMI with the severity of COVID-19 might be of paramount importance in Mexico, where the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults is 39.1% and 36.1%, respectively24. Consequently, this emerging risk factor could trigger a wave of young patients presenting with severe COVID-19 with requirements of IC and, therefore, with the possibility of jeopardizing the public and private health-care service capacity in our country. Further studies are warranted to corroborate our findings.

Comprehensive knowledge of the factors related to COVID-19 complications as well as their early identification is essential components for identifying subjects that could safely receive ambulatory care. Compared to outpatients, inpatients were older and reported T2DM and hypertension more often. We also found a higher proportion of people living with diabetes among ICU patients than in non-ICU patients. As in the case of aging, the presence of comorbidities (e.g., diabetes and hypertension) is well-known risk factors for COVID-19 complications25-28. Both, inpatients and patients with ICU requirements presented with symptoms and signs suggestive of pneumonia more frequently8. In contrast, outpatients complained more about upper respiratory tract symptoms, maybe indicative of an earlier stage of the disease.

When compared to non-ICU inpatients, patients with requirement of IC presented several laboratory parameters (at baseline and over time), that were suggestive of a more intense inflammatory response, a more severe pro-thrombotic state, and a higher frequency of cardiac and liver involvement. All of these features have been previously related to worse outcomes, including the need of IC and death1,8,9,18,29,30.

These features (i.e., clinical, epidemiological, and laboratorial) could be useful in hospitalization-decision making, simplifying early identification of complications, and improving their prediction. In fact, our institutional guidelines are based on a simple evaluation at triage aimed at the early identification of complications and their related factors. Our guidelines contemplate two predictive bedside scores to identify patients with complications and patients at risk of worse outcomes (i.e., qSOFA and NEWS). Both are recommended for sepsis screening and have been shown to predict mortality and IC requirements31. According to our findings, these scores were higher in ICU patients when compared to non-ICU subjects. We also found a higher MuLBSTA score, a tool that was explicitly developed to assess 90-day mortality in patients with viral pneumonia17. Although we found all of them useful, further studies are required to assess their diagnostic and predictive capability for complications and worse outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

This study has several limitations: (a) the patients included are part of a still ongoing cohort study, and thus the results represent preliminary data on the initial evaluation of COVID-19 patients during the 1st weeks of the pandemic; (b) since many patients are currently hospitalized, their follow-up still is limited, and therefore, several endpoints are unknown; (c) outpatients were not systematically followed-up during this stage, and thus in some patients their outcomes are unknown; (d) this preliminary data does not allow to analyze the impact of treatment modalities; moreover, the mortality analysis is limited in that patients evaluated for this outcome represented only half of the included population; and (e) these data come from a single tertiary care center, and therefore, the availability of laboratory tests, facilities, and/or treatment modalities may not be generalized to every center in Mexico and Latin America.

In conclusion, patients with COVID-19 diagnosis were middle-aged obese or overweight men. Older individuals with comorbidities presenting with fever, cough, or dyspnea were most likely to be admitted. Inpatients with history of diabetes, high BMI, and clinical or laboratory features compatible with a severe inflammatory state were more likely to require IC.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)