INTRODUCTION

The virus now referred as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged late 2019 in the Wuhan region in China. Since then, and up to April 3, 2020, around one million cases have been documented throughout the world in at least 181 different countries and regions1-3. The World Health Organization has declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a global pandemic, which implies efficient infectious mechanisms and a global spread of SARS-CoV-24. In the United States of America, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed and published a series of guidelines to orient health-care systems on how to deal with pandemics, one of the main goals being the installation of protocols to provide better population healthcare4. Without a doubt, the surge capacity for massive critical care requires organizing the health system’s response effort. As cases have started to appear in Latin America, first in Brazil, and shortly after in Mexico, planning the delivery of adequate resources for vulnerable patients is essential to reduce overall mortality and to optimize the distribution of supplies4,5.

Epidemiologic reports of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic have consistently shown older adults as a, particularly vulnerable population to severe forms of disease, as well as to worse health-related outcomes such as the need for mechanical ventilation (MV), hospitalization in intensive care units (ICU), and higher mortality risk6. It has also been hypothesized, that the incubation time of SARS-CoV-2 among older adults is shorter, as well as the progression from the appearance of symptoms to the worsening of the overall state7,8. Guan et al. reported that severe forms of the disease, as well as other composite primary outcomes (length of stay in the ICU, MV, and death), were more common in older adults compared with younger groups (32.8% vs. 18.0%) and that milder forms of the disease were more common among younger patients6.

Knowing that the COVID-19 pandemic importantly affects older adults, which represent the group with the highest number of comorbidities, there is a need to develop strategies to identify older persons at a higher risk of disease-related complications, as well as those with a higher likelihood of having a satisfactory response to treatment (including invasive measures). In regions like Latin America, the steady growth of the older adult population emphasizes the need of being prepared for providing care for them during events like the current pandemic and to develop strategies adapted to locally available resources9.

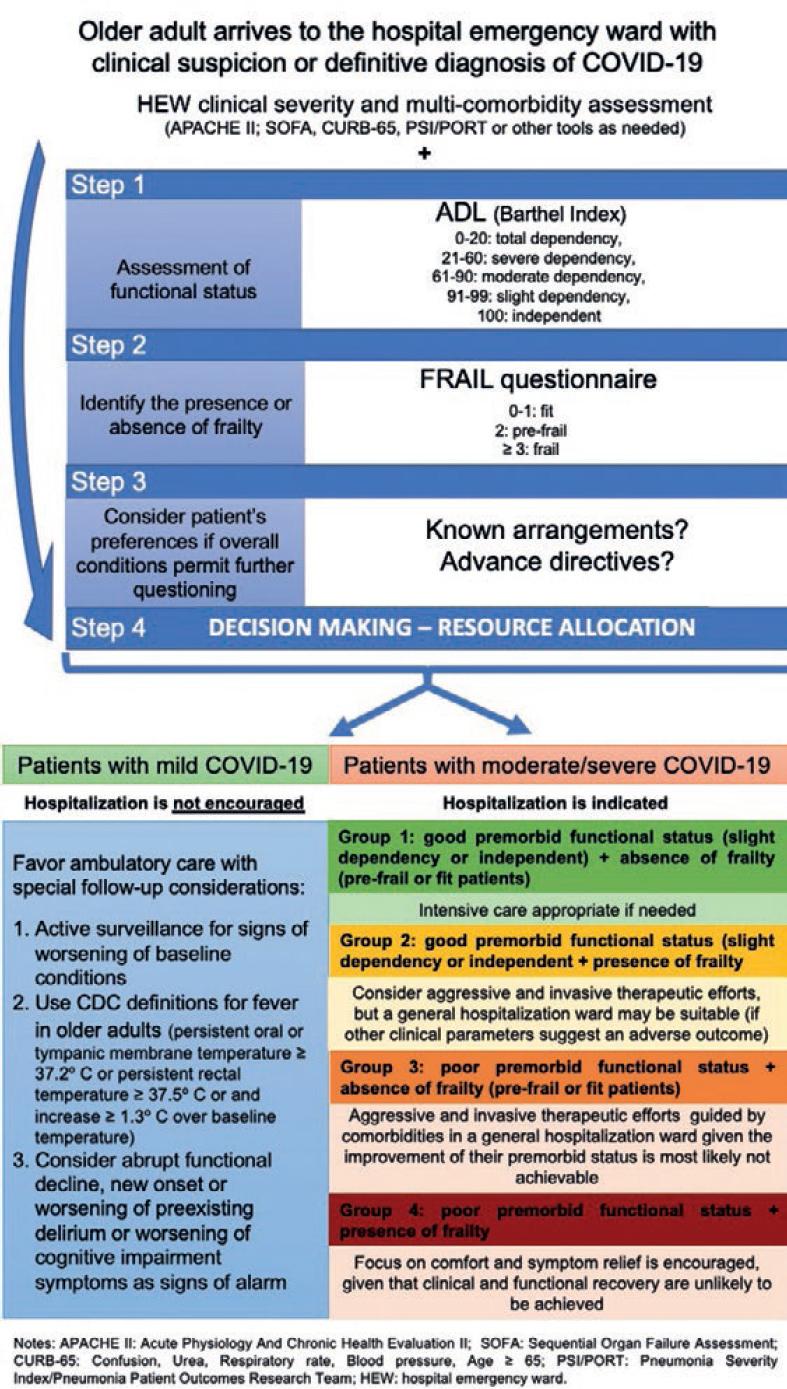

Implementing massive critical care demands deploying simple response teams with pre-established and standardized protocols to increase accountability of care, and facilitate care during a disaster event. Therefore, the objective of this review is to propose a pathway to assist in the decision-making process for hospital resource allocation for older adults with COVID-19, including ICU admission, using simple geriatric assessment-based tools, which can be easily implemented in resource-limited settings.

STRATEGIES FOR THE CATEGORIZATION OF OLDER ADULTS WITH COVID-19 IN RESOURCE-LIMITED SETTINGS

Although older age is known to increase the risk for COVID-19 associated complications, other health problems specifically seen among older adults should be taken into account to identify those with a worse prognosis beyond chronological age, for example, the presence or absence of frailty, functional status, and multi-multimorbidity, might be better predictors for complications in older adults with acute illnesses.

Frailty and functional status have been largely and consistently related to adverse health-related outcomes, and those results have been replicated in diverse scenarios of medical care. Frailty describes a predominantly biological syndrome, product of a diminished homeostatic reserve and poor resilience, which in turn increases the vulnerability of an individual, and correlates with a larger use of health-care services, risk of immobility, disability, and death in diverse settings10-15. On the other hand, multi-comorbidity has been recently envisioned as an entity that correlates with synergistic poor health-related outcomes and complex management, rather than just a numerical descriptor of clinical conditions or an inventory of diseases16. In the case of hospitalized adults with COVID-19, age-related conditions including hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular, and lung diseases have been reported as the mainly found comorbidities17,18. Thus, it would be biologically plausible that frail and multi-comorbid individuals who develop severe manifestations of COVID-19 would have the worst expected outcomes10.

The standard of reference regarding the quality of care for older adults and detection of geriatric syndromes is the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), which is a method that provides valuable diagnostic information, including the presence of frailty, functional status, and multimorbidity, and establishes goals of care during the evaluation of older patients. However, performing a CGA is time consuming and requires special training, making its implementation in critical care challenging.

To identify those patients who are frail and distinguish them from those in good health conditions (often referred as non-frail or “fit”), critical care providers that are not familiar with CGA have at their disposition various tools, which have been developed and evaluated for their use in the hospital emergency ward (HEW)19-21. These tools might be of major relevance in contingency situations like the one we are now facing, given their easy implementation by non-geriatricians11.

Decision making to allocate health-care resources for the adequate care of older patients is a complex process. Therefore, considering the current knowledge about SARS-CoV-2, we propose that health-care professionals caring for older patients in the HEW should first identify persons with greater risk of complications associated to their individual characteristics and disease severity, as they do for every patient, and then categorize them according to the presence or absence of frailty, and baseline functional status.

It is important to emphasize that chronological age alone should not be used as the sole parameter to decide which patients should receive care and that our recommendations under no circumstances intend to endorse refusing medical care to older adults. In contrast, this approach seeks to achieve a tailored model of care that considers each patient’s specific needs and expects to avoid situations in which health-care professionals are forced to refuse life-sustaining care based on chronological age. This approach could also work for improving decision-making at triages, since multi-comorbidity, functional status, and frailty are better correlates of clinical and geriatric outcomes.

For logistical purposes, we propose a stepwise approach for categorizing older patients with COVID-19. In routine clinical practice, multi-comorbidity and disease severity are frequently evaluated at the same time, and their assessment is the standard of care in the HEWs. The additional proposed steps (assessment of functional status and frailty) should only add minutes to the initial work-up. If the patient is unresponsive or in a critical state, a proxy evaluation could be performed from the information provided by the closest family member or caregiver.

STEP 1: ASSESSMENT OF FUNCTIONAL STATUS

Functional status must be assessed in all older adults with suspected COVID-19 since it provides a better insight of the patient’s general condition than age alone. The assessment must consider the premorbid state of the patient and not the functional status at the time of the first medical evaluation in the HEW, which may underestimate the actual state of the patient.

To standardize the time frame and scales used for the evaluation of functional status, a period of 14 days before the initial assessment should be considered. We suggest using the Barthel index, which evaluates the individual capacity to perform 10 basic activities of daily living: Feeding, bathing, grooming, dressing, bowel control, Cladder control, toileting, chair transfer, ambulation, and stair climbing (Table 1). The Barthel index is scored from 0 (completely dependent) to 100 (completely independent), with items rated based on the amount of assistance required to complete each activity. A score of 0-20 indicates “total dependency,” 21-60 indicates “severe dependency,” 61-90 indicates “moderate dependency,” and 91-99 indicates “slight dependency.” Given its replicability and easy implementation in diverse clinical settings, this is a useful tool to assess functional status in a rapid manner22,23.

Table 1 Barthel index for functional evaluation22

| Barthel index* | |

|---|---|

| Activity | Score |

| Feeding | – 0 = Unable – 5 = Needs help cutting, spreading butter, etc., or requires modified diet – 10 = Independent |

| Bathing | – 0 = Dependent – 5 = Independent (or in shower) |

| Grooming | – 0 = Needs help with personal care – 5 = Independent face/hair/teeth/shaving (implements provided) |

| Dressing | – 0 = Dependent – 5 = Need help but can do about half unaided – 10 = Independent (including buttons, zips, laces, etc.) |

| Bowels | – 0 = Incontinent (or needs to be given enemas)

– 5 = Occasional accident – 10 = Continent |

| Bladder | – 0 = Incontinent, or catheterized and unable to manage

alone – 5 = Occasional accident – 10 = Continent |

| Toilet use | – 0 = Dependent – 5 = Needs some help, but can do something alone – 10 = Independent |

| Transfers (bed to chair and back) | – 0 = Unable, no sitting in balance – 5 = Major help (one or two people, physical), can sit – 10 = Minor help (verbal or physical) – 15 = Independent |

| Mobility (on level surfaces) | – 0 = Immobile or < 50 yards – 5 = Wheelchair independent, including corners, > 50 yards – 10 = Walks with the help of one person (verbal or physical) > 50 yards – 15 = independent (but may use any aid; for example, stick) > 50 yards |

| Stairs | – 0 = Unable – 5 = Needs help (verbal, physical, carrying aid) – 10 = Independent |

*1. The Index should be used as a record of what a patient does, not as a record of what a patient could do. 2. The main aim is to establish degree of independence from any help, physical or verbal, however minor and for whatever reason. 3. The need for supervision renders the patient not independent. 4. A patient’s performance should be established using the best available evidence. Asking the patient, friends/relatives and nurses are the usual sources, but direct observation and common sense are also important. However, direct testing is not needed. 5. Usually, the patient’s performance over the preceding 24-48 h is important, but occasionally longer periods will be relevant. 6. Middle categories imply that the patient supplies over 50% of the effort. 7. Use of aids to be independent is allowed.

STEP 2: IDENTIFYING THE PRESENCE OR ABSENCE OF FRAILTY

To achieve this objective, we suggest using the FRAIL questionnaire, which was developed for frailty identification by non-geriatricians (Table 2). The questionnaire is composed of 9 items and takes an estimated 5 min for its application (with the option of being self-administered or performed by a health-care professional)24. It has shown an adequate correlation between diverse geriatric outcomes and properly categorizes older adults in frail, pre-frail, and fit. The questionnaire has a good correlation with mortality, being highest in the frail group. This questionnaire even has several cross-cultural validations which further ensure its usefulness worldwide25.

Table 2 FRAIL questionnaire for identifying frailty among older adults24

| FRAIL questionnaire | |

|---|---|

| Item* | Question/criteria for positive score |

| F – Fatigue Is the patient easily fatigued? | Does the patient have difficulty walking a quarter of a

mile? – Some, a lot, unable to do AND Does the patient have difficulty performing housework such as washing windows or scrubbing floors? – Some, a lot, unable to AND Activity in a typical 24-h day – No moderate or vigorous activity |

| R – Resistance Is the patient unable to walk up one flight of stairs | Pre-injury level of activity for climbing stairs:

–Unable to do |

| A – Ambulation Is the patient unable to walk one block? | Does the patient have difficulty walking a quarter of a

mile? – A lot, unable to do |

| I – Illnesses Does the patient have more than five illnesses? | Number of comorbidities |

| L – Loss of weight Has the patient lost more than 5% of weight in the past 6 months? | Lost 5 pounds or more in the past 3 months without

trying? – Yes AND/OR Unintended weight loss = – Yes |

*0-1 positive items categorize the patient as “fit,” 2 positive items categorize the patient as “pre-frail,” and 3 or more positive items categorize the patient as “frail.”

STEP 3: CONSIDER THE PATIENTS’ PREFERENCES

We consider that it is important to take a moment and interrogate the patient or their family, regarding their preferences in subjects such as willingness to be admitted to the hospital and/or to go through invasive maneuvers. Evidence shows that some older adults consider the adverse events of the treatment (in this case treatment may include hospitalization, continuous monitoring, use of oxygen, or even need for MV) of equal or more important than their beneficial effects, and may even choose to decline treatment to avoid said adverse events26. We suggest using this step to question the patients and/or their family about goals and preferences of treatment, advance directives, etc., to include the patients’ goals in the resource-allocation decision.

After the evaluation of multi-comorbidity and functional status, categorizing frailty, and establishing the patients’ preferences, we would have the following possible scenarios for resource allocation:

STEP 4: CLINICAL SEVERITY OF COVID-19 AND DECISION MAKING

Patients with mild presentation of COVID-19

Older adults with a mild presentation of COVID-19 should follow the recommendations of isolation and care as the rest of the population that falls in this category, regardless of their age. However, some considerations must be made:

Older adults may get worse faster than their younger counterparts; family and caregivers must be actively vigilant for any change in their baseline conditions once the diagnosis has been made.

-

Older adults may not present overt fever; clinicians and caregivers must consider the following temperature measurements to define fever in the elderly, as established by the CDC27:

-

Older adults may present an atypical worsening of their conditions. Health-care professionals, family, and caregivers should consider the following as signs of worsening conditions and should act accordingly:

Abrupt functional decline.

New onset of delirium.

Worsening of previously documented delirium28.

In patients with baseline cognitive impairment, worsening of known symptoms may be the only manifestation of acute illness.

Establishing the presence of frailty is encouraged in this group. Patients with mild disease AND frailty could be at high risk for complications and mortality. Hospitalization may be desirable in this group; however, if the local resources are precarious, ambulatory care may also be adequate for these patients.

Patients with moderate to severe COVID-19

We propose that resources for this group of patients should be allocated according to their comorbidities and the assessments stated in Steps 1 and 2:

Patients with a good premorbid functional status include those categorized as “slightly dependent” (91-99 points) or “completely independent” (100 points), according to the Barthel index23. Patients with “moderate dependency” or worse should be considered as having a poor premorbid functional status. Likewise, the presence or absence of frailty should be noted using the tools mentioned in Step 2.

Based on their comorbidities, and on these two parameters, older patients with moderate/severe COVID-19 could be further classified into the following groups (as depicted in figure 1):

Group 1: Good premorbid functional status + absence of frailty (pre-frail or fit patients)

This group includes those older adults who would most likely respond favorably to treatment, have a better mortality prognosis, and if recovery is achieved, they would be expected to return to their baseline functional status. Patients in this group should be considered as good candidates to aggressive and invasive therapeutic efforts, including, but not limited to, ICU admission.

Group 2: Good premorbid functional status + presence of frailty

This group of patients includes older adults with higher morbidity and mortality risks associated with prevalent frailty. Patients in this group could be considered for aggressive and invasive therapeutic efforts, but a general hospitalization ward may be more suitable for their care if other clinical parameters suggest an adverse outcome.

Group 3: Poor premorbid functional status + absence of frailty (pre-frail or fit patients)

This group includes older adults who were highly dependent before their initial assessment. In the absence of frailty, mortality risk may not be as high as in the other groups. However, patients in this group could also be considered for aggressive and invasive therapeutic efforts in general hospitalization ward given that the improvement of their premorbid status is most likely not achievable.

Group 4: Poor premorbid functional status + presence of frailty

Patients in this group have a poor baseline condition and a high mortality risk. Therefore, the ideal goals of care for these patients should be to focus on comfort and symptom relief given that clinical and functional recoveries are unlikely to be achieved.

It is important to emphasize that, as more characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 infection are known, other clinical and biochemical parameters will emerge to help us guide more accurately our decision-making process. Although this is a dynamic situation, and with constant updating, it is significant to standardize a model to categorize resource allocation for older adults with COVID-19 based on the currently available information. We believe that this model could be implemented across the HEWs in resource-limited settings and we have begun to implement it at our own institution.

CONCLUSIONS

We must highlight the fact that, as in every medical decision, clinical judgment cannot and should not be substituted. The patient categories proposed in this report have the only objective of helping health-care professionals in their decision-making process in this particularly hard time and in a scenario, such as ours, of limited resources and not necessarily with a geriatrician as part of their team.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)