Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista de investigación clínica

versão On-line ISSN 2564-8896versão impressa ISSN 0034-8376

Rev. invest. clín. vol.58 no.3 Ciudad de México Mai./Jun. 2006

Artículo original

Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after preoperative chemoradiation therapy and low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision for locally advanced rectal cancer

Factores de riesgo para la fuga anastomótica después de quimio–radioterapia preoperatoria y resección anterior baja con excisión total de mesorrecto para cáncer de recto localmente avanzado

Saúl E. Rodríguez–Ramírez,* Arizbeth Uribe,* Erika Betzabé Ruiz–García,*Sonia Labastida,** Pedro Luna–Pérez*

* Colorectal Service. Surgical Oncology Department.

** Medical Statistical Department, Hospital de Oncología, Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social.

Correspondence and reprint request:

Pedro Luna–Pérez M.D.

Puerto México 53–101 Col. Roma Sur,

06760, México, D:F.

Fax: (+525) 564–8000;

E–mail: lunapp@infosel.net.mx

Recibido el 29 de abril de 2005.

Aceptado el 15 de febrero de 2006.

ABSTRACT

Background. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after preoperative chemoradiation plus low anterior resection and total mesorectal excision remain uncertain.

Objective. To analyze, the associated risk factors with colorectal anastomosis leakage following preoperative chemo–radiation therapy and low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer.

Materials and methods. Between January 1992 and December 2000, 92 patients with rectal cancer were treated with 45 Gy of preoperative radiotherapy and bolus infusion of 5–FU 450 mg/m2 on days 1–5 and 28–32, six weeks later low anterior resection was performed. Univariate analysis was performed as to find the risk factors for colorectal anastomotic leakage.

Results. There were 48 males and 44 females, mean age was 55.8 years. Mean tumor location above the anal verge was 7.4 ± 2.6 cm. Preoperative mean levels of albumin and lymphocytes were 3.8 g/dL and l,697/mL, respectively. Mean distal margin was 2.9 ± 1.4 cm. Multivisceral resection was performed in 11 patients (13.8%), 32 patients (35%) had diverting stoma. Mean preoperative hemorrhage was 577 ± 381 mL, and 27 patients (24%) received blood transfusion. Ten patients (10.9%) had anastomotic leakage. No operative mortality occurred. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage were: gender (male) and tumor size > 4 cm. Three patients of the group without colostomy required a mean of six days in the unit of intensive care; mean time of hospital stay of patients with and without protective colostomy was 12.4 ± 4.5 days vs. 18.3 ± 5.2 days (p = 0.01).

Conclusion. In male patients with rectal adenocarcinoma measuring > 4 cm, treated by preoperative chemoradiotherapy + low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision, a diverting stoma should be performed to avoid major morbidity due to anastomotic leak.

Key words. Anastomotic. Leakage. Chemotherapy. Radiotherapy. Total majorectal excision. Colostomy.

RESUMEN

Antecedentes. Los factores de riesgo para la fuga de anastomosis colo–rectal después de quimio–radioterapia preoperatoria con excisión total de mesorrecto permanecen aún inciertos.

Objetivo. Analizar los factores de riesgo asociados con la fuga o filtración de anastomosis colorrectal que sigue a la terapia de radiación química y a la extirpación anterior baja con total excisión mesorrectal para el cáncer rectal.

Materiales y métodos. Entre enero de 1992 y diciembre de 2000, 92 pacientes con cáncer rectal fueron tratados con 45 Gy de radioterapia preoperativa e infusión del bolo de 5'FU450 mg/m2 administrados los días 1–5 y del 28–32; seis semanas más tarde, se realizó la extirpación anterior baja. Se llevó a cabo un análisis univariado en cuanto a encontrar los factores de riesgo de la fuga anastomótica colorrectal.

Resultados. Se trató a 48 varones y 44 mujeres cuya media etaria fue de 55.8 años. La localización media del tumor arriba del borde anal fue de 7.4 ± 2.6 cm. Los niveles medios preoperativos de albúmina y linfocitos fueron de 3.8 g/dL y 1,697/mL, respectivamente. El margen distal medio fue de 2.9 ± 1.4 cm. La extirpación multivisceral fue realizada en 11 pacientes (13.8%); 32 pacientes (35%) tuvieron una colostomía derivativa. La hemorragia preoperativa media fue de 577 ± 381 mL, y 27 pacientes (24%) recibieron transfusión sanguínea. Diez pacientes (10.9%) tuvieron fuga anastomótica. No hubo ningún deceso quirúrgico. Los factores de riesgo para la fuga anastomótica fueron: el género (masculino) y el tamaño del tumor > 4 cm. Tres pacientes del grupo sin colostomía requirieron una media de seis días en la UTI (Unidad de Terapia Intensiva); el promedio media de la duración hospitalaria de pacientes con y sin colostomía protectiva fue de 12.4 ± 4.5 días contra 18.3 ± 5.2 días (p = 0.01).

Conclusión. En pacientes masculinos con adenocarcinoma rectal que mide > 4 cm, tratados mediante radioterapia química preoperativa + extirpación anterior baja con excisión total mesorrectal, debería realizarse una abertura que se desvíe a fin de evitar una mayor mortalidad debida a fuga anastomótica.

Palabras clave. Fuga anastomótica. Quimioterapia. Excisión mesorrectal. Colostomía. Radioterapia preoperativa.

INTRODUCTION

With the advent of stapling devices and their increasing use to create low colorectal anastomosis, low anterior resection with preservation of the anal sphincter has become the preferred surgical option of choice for mid and low rectal cancer.1

The administration of preoperative chemo–radiation therapy (PCRT) and the use of total mesorectal excision (TME) increase the rate of anal sphincter preservation in locally advanced mid and low rectal cancer. However, both are associated with high risk of surgical morbidity. The former with pelvic infection and the later with anastomotic leakage.2,3 The associated mortality ranges between 0% and 25%.4,5

The main objective of the current study was to identify the associated risk factors for anastomotic leakage following PCRT and low anterior resection (LAR) with TME for mid and low rectal cancer.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

From January 1992 to december 2000. Ninety–two patients with histologically proven rectal adenocarcinoma located between 4 and 10 cm from the anal verge were treated at the Hospital de Oncología, Centro Médico Nacional, Siglo XXI of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social located in Mexico City. Distance between the anal verge and the distal limit of the tumor was determined by rigid rectoscopy with patients placed in a jackknife position.

Pretreatment evaluation includes: medical history; physical examination; complete blood cell count; chemistry profile; determination of carcinoembryonic antigen; chest X–ray, and computed tomography of the abdomen, pelvis and perineum; additionally, since January 1995, the evaluation included endorectal ultrasound. Colonoscopy was performed in all patients, except in those cases with rectal tumor stenosis.

Inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: tumor penetration through the muscularis propia and perirectal fat or metastatic lymph nodes; tumors attached to neighboring pelvic organs or tither or fixed to the pelvic sidewall; age under 75 years; ECOG performance status 0–2; white blood cell count of at least 4,000/mm3; platelet count of at least 100,000/mm3, and normal liver and renal function tests. Patients with distant metastatic disease at the time of pretreatment evaluation were excluded from the study. Only patients who underwent total mesorectal excision were included.

Scheduled treatment

The radiation therapy was delivered with an 8–Mev linear accelerator using a two– or three–field technique with the patient in a prone position with distended bladder. The top of the field was placed at midpoint of the body of L5; the lateral borders 1 cm outside the bony pelvis, and the inferior margin at the anal verge. A dose of 45 Gy was administered at 1.8 Gy/day for 5 days per week during five consecutive weeks. 5–Fluorouracil at doses of 450 mg/m2 was administered as a bolus infusion 1 h prior to the administration of radiotherapy on days 1–5 and 28–32. Acute toxicity from chemoradiation therapy was closely monitored and assessed according to the criteria of the World Health Organization.6

Four weeks after the completion of chemoradiation therapy, re–staging procedures were performed which included the following physical examination; computed tomography of the abdomen, pelvis and perineum; chest x–ray; complete blood cell count; biochemical profile, and rectosigmoidoscopy or full colonoscopy.

Bowel lavage with 3–4 L of polyethylenglycol was carried out the day prior to surgery, concomitantly with oral ingestión of antibiotics (neomycin, erytromycin). Two hours before surgery, 1 g of second–or third– generation cephalosporin was intravenously administered and continued for three daily doses until the second postoperative day. One hour before surgery, 5,000 IU of subcutaneous heparin was administered and after surgery, every 12 hr, until the patient was fully mobile.

Patients underwent surgery in the dorsal lithotomy position. An abdominal midline incision was performed, followed by meticulous exploration of the abdominal cavity to search for any possible metastatic disease. All abnormal findings were biopsed. The inferior mesenteric artery was ligated at its origin from the aorta, or immediately under the ascending left colic artery. The left colon and splenic flexure were mobilized and the inferior mesenteric vein was ligated below the lower edge of the pancreas to achieve a tension–free anastomosis. A complete mesorectal and pararectal dissection was performed according to the method described by Heald et al.,7 preserving the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. Before rectal transection, a povidone–iodine solution irrigation was carried out. The anastomoses were performed using single –or double– stapled technique. Stapler doughnuts were always inspected and microscopically studied. Anastomotic integrity was tested with per–anal insufflations.

Resected specimens were studied under the manual and/or modified clearing technique to identify lymph nodes.8 Surgical specimens were classified according to the TNM (American Joint Committee on Cancer) stage classification.9

Decision to perform transverse diverting colostomy was to criteria of surgeons. In general they were the following: technical difficulties, narrow pelvis, intraoperative bleeding, low colo–rectal anastomosis (< 4 cm), and sohen in doubt of anastomotic integrity.

Perioperative morbidity was defined as occurring within 30 days of surgical intervention or after, if the cause was clearly surgically related. Major morbidity was defined as complications requiring surgical treatment, a prolonged hospital stay, and life–threatening complications. Definition of anastomotic leakage was clinical as the presence of gas, pus or fecal discharge from the drain, pelvic abscess, peritonitis, discharge of pus per rectum, rectovaginal or recto–bladder fistula. All anastomotic leakages were confirmed by water–soluble contrast enema or transanal instillation of blue–dye.

The  test or Fisher's exact test were used for univariate analysis, a p value of < 0.05 was considered as significant.

test or Fisher's exact test were used for univariate analysis, a p value of < 0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

There were 48 males and 44 females, with a mean age of 55.8 ± 12.7 years. Sixteen patients (17.4%) had diabetes mellitus, 13 had arterial hypertension and 10 mixed cardiopathy. Tumors were located between 3–7 cm (n = 56) and 7.1–10 cm (n = 36) from the anal verge. Mean tumor location above the anal verge was 7.4 ± 2.6 cm. Clinically, 15 patients (16.3%) had tumor attachments to neighboring pelvic organs, or tumor attachments that were tethered or fixed to the pelvic sidewall.

All patients received the pre–scheduled treatment. Average preoperative levels of albumin and lymphocytes were 3.8 ± 0.5 g/dL and 1,697 ± 925 /\ih, respectively. At exploratory celiotomy, 11 patients (13.8%) had tumor attachments to neighboring pelvic organs that required a low anterior resection plus the following pelvic organs in block: bladder (n = 5); uterus (n = 4), ileum (n = 1), and bladder, seminal vesicles and prostate (n = 1). Colorectal anastomoses were performed as follows: double stapling technique (n = 47) and single stapling (n = 45). Mean distal margin was 2.9 ± 1.4 cm.

Mean intraoperative hemorrhage was 577 ± 381 ml and 27 (29.3%) received blood transfusion. Mean operative time was 298 ± 85 min., no operative mortality occurred. Thirty–two patients (35%) had protective colostomy. Demographic characteristics of those patients with and without protective colostomy are shown in table 1. Postoperative complications are shown in table 2. Treatment of patients with anastomotic leakage is shown in figure 1. Three patients of the group without colostomy required a mean of six days in the unit of intensive care; these patients required new surgery for intestinal occlusion, evisceration and persistent intra–abdominal sepsis. No patients in the group with colostomy needed intensive care unit. Mean time of hospital stay of patients who underwent protective colostomy was 12.4 ± 4.5 days us. 18.3 ± 5.2 days in those without protective colostomy (p = 0.01).

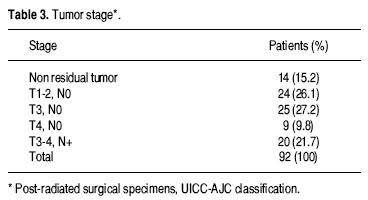

Tumor stages are shown in table 3. Univariate analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage are shown in table 4. After a median follow–up of 37 months, four patients (4.3%) had local recurrence and 15 (16.3%) had distant metastatic disease.

Colostomies were closed at a mean time of 10 weeks. Surgical approach to colostomy closure was: peristomal, in 30 patients and mid–line exploratory celiotomy in eight. Twelve patients (31.6%) had morbidity after colostomy closure. Five of them had major complications (intestinal obstruction, three; anastomotic leakage, one and evisceration, one), three required surgical re–intervention and in all these patients new stoma was performed. Seven patients had minor complications: abdominal wall infection (n = 4) and abdominal wall hernia (n = 3). In three patients the stoma was no closed; two of them due to intensive pelvic fibrosis after Hartmann's procedure, one for anastomotic stenosis; and two patients developed anal incontinence that required new surgical intervention to perform permanent stoma. Intestinal continuity was maintained in 87/92 patients (94.5%).

DISCUSSION

The 10.9% rate of clinical anastomotic leakage after colorectal anastomoses in the current series is comparable to the 6.5%–18% rate reported in recent studies.10–16 Anastomotic leakage can be caused by multiple factors such as: gender; preoperative radiation therapy; bowel preparation; anastomosis level; surgeon's experience; anastomotic technique; protecting stomas; peritoneal sepsis; duration of surgery; the presence of chronic disease, and nutritional status.17–22 However, the clinical importance of these isolated different factors remains uncertain.

Multivariate analysis can help identify a risk pattern for anastomotic leakage. Vignali, et al.23 reported a rate of 2.9% of clinical anastomotic leakage in 1,040 patients; occurring in 22/284 patients (7.7%) with an anastomosis level within 7 cm from the anal verge and 1% (7/730 patients) after high anastomotic level (> 7 cm from the anal verge). By univariate analysis the significant risk factors were: diabetes mellitus, use of pelvic drainage, and duration of surgery. Multivariate analysis identified the anastomotic distance from the anal verge within 7 cm as the only risk factor. Golub R, et al.,24 reported a series of 764 patients who underwent 813 intestinal anastomoses, with an overall rate of anastomotic leakage of 3.4%. Multivariate analysis identified the following risk factors for anastomotic leakage: serum albumin level of less than 3.0 g/L, use of corticosteroids, peritonitis, bowel obstruction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and perioperative blood transfusion of more than two units. However, both series mixed inflammatory with neoplasic disease, colon and rectal anastomoses and were unsuccessful to find the risk pattern for anastomotic leakage in patients who underwent PCRT plus low anterior resection with TME.

Pakkastie, et al.,11 reported a series of 134 patients and their rate of anastomotic leakage was 12%. The only independent risk factor for anastomotic leakage was the anastomosis from the anal verge, 27% in the anastomosis located < 7 cm from the anal verge us. 0% above 7 cm. Rullier, et al.,25 reported a series based on 272 anterior resections for rectal cancer performed by the same surgical team. Clinical anastomotic leakage was 12%. Multivariate analysis showed that male gender (2.7 RR) and anastomosis level within 5 cm from the anal verge (6.5 RR) were the main risk factors for anastomotic leakage. In low anastomosis located within 5 cm of the anal verge, obesity was statistically associated with anastomotic leakage. These risk factors also were observed in the current series. However, in the former series patients did not receive preoperative radiotherapy and in the later series, only 28 patients received preoperative radiotherapy and 19 received intraoperative radiotherapy, the rate of anastomotic leakage was 14% and 21%, respectively.

Law, et al..26 reported a series of 196 patients treated by low anterior resection with TME and low colorectal or coloanal anastomosis, in this series no data were recorded regarding the administration of preoperative radiotherapy. Their rate of anastomotic leakage was 10.2% and the risk factors found by multivariate analysis were male gender and the presence of a diverting stoma. In the current series, the male gender risk factor was confirmed, but not the presence of diverting stoma.

The presence of diverting stoma remains a controversial issue, as risk factor for anastomotic leakage. Karanjia, et al.,15 Carlsen, et al.,12 and Dehni, et al.,21 demonstrated significant decrease on incidence of clinical anastomotic leakage in patients with diverting stoma. Furthermore, Heald, et al.,10 reported a temporary stoma in 73% of their patients. However, Pakkastie, et al.,11 and the results of the current series showed that proximal diversion did not reduce the anastomotic leakage rate. The authors agree with Wexner, et al.,28 that the presence of a diverting stoma does not decrease the rate of anastomotic leakage, but it does decrease the incidence of disseminated fecal peritonitis.

Preoperative radiation therapy has been related with high incidence of pelvic and perineal wound infection however its role in increasing the rate of colorectal anastomotic leakage remains uncertain. The Stockholm Colorectal Cancer Study Group and the Basingstoke Bowel Cancer Research Project13 reported a comparative study where no differences in anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection between patients treated by preoperative radiotherapy and those treated with TME without preoperative radiotherapy (10% and 9% us. 9%, respectively) were found.

The value of preoperative radiotherapy in conjunction with TME is controversial because selected series reported local recurrences under 5%.10 The Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group2 reported the results of a trial comparing patients receiving preoperative radiotherapy (short term) plus TME and those related with TME only. Results after two years of follow–up showed significant difference in local recurrence in favor of the former group (2.4 vs. 8.2%, p < 0.001). However, high incidence of perineal wound complications was found in the group of patients treated by abdominoperineal resection plus combined treatment (26%) vs. those treated with abdominoperineal resection plus TME only (18%) p = 0.05. However, no differences with regard to postoperative morbidity and mortality between both groups were reported. Pucciarelli, et al.,29 reported that the administration of PCRT did not affect the postoperative complications after low anterior resections.

Recently, Gasstinger, et al.,30 reported a series with 2,729 patients underwent LAR, 881 of them received a protective stoma after LAR. Overall anastomotic leak rates were similar in patients with or without a stoma (14.5 vs. 14.2%). The incidence of leaks that required surgical intervention was significantly lower in those with a protective stoma (3.6 vs. 10.1%; p = 0.03). Logistic regression analysis showed that provision of a protective stoma was the strongest independent factor for the avoidance of anastomotic leak that required surgical intervention (p < 0.001). In the current series similar results were found diminishing the severity of intra–abdominal sepsis, admission in the intensive care unit and the rate of hospital stay.

CONCLUSION

The results of the current series found the following risk factors associated with anastomotic leakage after PCRT and low anterior resection with TME: male patients and tumors measuring > 4 cm. In these patients a diverting stoma should be performed as to avoid major morbidity by anastomotic leakage.

REFERENCES

1. Heald RJ, Smedth RK, Kald A, Sexton R, Moran BJ. Abdominoperineal excision of the rectum: an endangered operation. Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40: 747–51. [ Links ]

2. Kapiteijin E, Marijnen CAM, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resecable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 38–46. [ Links ]

3. Karanjia ND, Corder AP, Holdsworth PJ, Heald RJ. Risk of peritonitis and fatal septicaemia and the need to defunction the low anastomosis. Br J Surg 1991; 78: 196–8. [ Links ]

4. Luna–Pérez P, Rodríguez–Ramírez S, González–Macouzet, Rodríguez–Coria DF. Tratamiento de la dehiscencia anastomótica secundaria a resección anterior baja por adenocarcinoma de recto. Rev Invest Clin 1999; 51: 23–9. [ Links ]

5. Mileski WJ, Joehl RJ, Rege RV, Nahrwold DL. Treatment of anastomotic leakage following low anterior resection. Arch Surg 1988; 123: 968–71. [ Links ]

6. Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer 1981; 47: 207–14. [ Links ]

7. Heald RJ. The Holy Plane of rectal surgery. J R Soc Med 1988; 81: 503–8. [ Links ]

8. Sánchez W, Luna–Pérez P, Alvarado I, Labastida S, Herrera L. Modified clearing technique to identify lymph node metastases in post–irradiated surgical specimens from rectal adenocarcinoma. Arch Med Res 1996; 27: 31–6. [ Links ]

9. Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, Kennedy BJ, Murphy GP, Lippimcott–Raven Publishers. Philadelphia, Penn.: American Joint Committee on Cancer. Colon and rectum; 1998, pp. 81–8. [ Links ]

10. Heald RJ, Moran BJ, Ryall RD, Sexton R, MacFarlane JK. Rectal cancer: the Basinsgtoke experience of total mesorectal excision, 1978–1997. Arch Surg 1998; 133: 894–9. [ Links ]

11. Pakkastie TE, Luukkonen PE, Jürvinen HJ. Anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of the rectum. Eur J Surg 1994; 160: 293–7. [ Links ]

12. Carlsen E, Schlichting E, Guldvog I, Johnson E, Heald RJ. Effect of the introduction of total mesorectal excision for the treatment of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 526–9. [ Links ]

13. Martling AL, Holm T, Rutqvist LE, Moran BJ, Heald RJ, Cedermark B. Effect of a surgical training program on outcome of rectal cancer in the county of Stockholm. Lancet 2000; 356: 93–6. [ Links ]

14. Benoist S, Panis Y, Alves A, Valleur P. Impact of obesity on surgical outcomes after colorectal resection. Am J Surg 2000; 179: 275–81. [ Links ]

15. Karanjia ND, Corder AP, Beam P, Heald RJ. Leakage from stapled low anastomosis after total mesorectal excision for carcinoma of the rectum. Br J Surg 1994; 81: 1224–6. [ Links ]

16. Kasperk R, Philipps B, Vahrmeyer M, Willis S, Schumpelick V. Risk factors for anastomosis dehiscence after very deep colorectal and coloanal anastomosis. Chirurg 2000; 71: 1365–9. [ Links ]

17. Averbach AM, Chang D, Koslowe P, Sugarbaker PH. Anastomotic leakage after double–stapled low colorectal resection: analysis of risk factors. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 780–7. [ Links ]

18. Irvin TT, Goligher JC. Etiology of disruption of intestinal anastomoses. Br J Surg 1973; 60: 461–4. [ Links ]

19. Goligher JC, Graham NG, De Dombal FT. Anastomotic dehiscence after anterior resection of rectum and sigmoid. Br J Surg 1970; 57: 109–18. [ Links ]

20. Moran B, Heald RJ. Anastomotic leakage after colorectal anastomosis. Semin Surg Oncol 2000; 18: 244–8. [ Links ]

21. Maas CP, Moriya Y, Steup WH, Kiebert GM, Klein Kranenbarg, Van de Velde JH. Radical and nerve–preserving surgery for rectal cancer in the Netherlands: a prospective study on morbidity and functional outcome. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 92–7. [ Links ]

22. Carlsen E, Schlichting E, Guldvog I, Johnson, Heald RJ. Effect of the introduction of total mesorectal excision for the treatment of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 526–9. [ Links ]

23. Vignali A, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, et al. Factors associated with the occurrence of leaks in stapled rectal anastomoses: a review of 1,014 patients. J Am Coll Surg 1997; 185: 105–13. [ Links ]

24. Golub R, Golub RW, Cantu Jr. R, Stein HD. A multivariate analysis of factors contributing to leakage of intestinal anastomoses. J Am Coll Surg 1997; 184: 364–72. [ Links ]

25. Rullier E, Laurent C, Garrelon JL, Michel P, Saric J, Parneix M. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 355–8. [ Links ]

26. Law WL, Chu KW, Ho JWC, Chan CW. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision. Am J Surg 2000; 179: 92–6. [ Links ]

27. Dehni N, Schlegel RD, Cunningham C, Guiguet M, Tiret E, Pare R. Influence of a defunctioning stoma on leakage rates after low colorectal anastomosis and colonic J pouch–anal anastomosis. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 1114–7. [ Links ]

28. Wexner SD, Alabaz O. Anastomotic integrity and function: role of the colonic J–pouch. Sem Surg Oncol 1998; 15: 91–100. [ Links ]

29. Pucciarelli S, Toppan P, Friso ML, et al. Preoperative combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy for rectal cancer does not affect early postoperative morbidity and mortality in low anterior resection. Dis Colon Rectum 1999; 42: 1276–83. [ Links ]

30. Gastinger I, Marusch F, Steinert R, et al. Protective defunctioning stoma in low anterior resection for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg 2005; 92: 1137–42. [ Links ]