Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista de investigación clínica

On-line version ISSN 2564-8896Print version ISSN 0034-8376

Rev. invest. clín. vol.57 n.6 Ciudad de México Nov./Dec. 2005

Artículo original

Incidence and risk factors for cutaneous adverse drug reactions in an intensive care unit

Incidencia y factores de riesgo en las reacciones adversas medicamentosas de tipo cutáneo en la unidad de cuidados intensivos

Maria del Mar Campos–Fernández,* Samuel Ponce–de–León–Rosales,** Carla Archer–Dubon,* Rocío Orozco–Topete*

* Department of Dermatology.

** Department of Hospital Epidemiology. Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán.

Correspondence and reprint request:

Dra. Rocío Orozco–Topete

Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán

Vasco de Quiroga 15, Col. Sección XVI

14080, México, D.F.

Phone: 52 (55) 5487–0900 ext 2435 Fax: 52 (55) 55282407

E–mail: rorozco@quetzal.innsz.mx

Recibido el 3 de junio de 2005.

Aceptado el 2 de septiembre de 2005.

ABSTRACT

Objective. To evaluate the incidence of adverse cutaneous drug reactions in intensive care unit patients.

Design. Cohort study.

Setting. General adult intensive care unit of an institutional tertiary care hospital.

Patients. Patients in the intensive care unit during a consecutive 8–month period were examined for adverse cutaneous drug reactions.

Results. Patients in the intensive care unit have an incidence of 11.6% of adverse cutaneous drug reactions. Associated risk factors were female gender, obesity, age over 60 and immune dysregulation (systemic lupus erythematosus, dysthyroidism, and antiphospholipid antibodies syndrome). Few patients had previous history of adverse cutaneous drug reactions. Antimicrobials were the main drug involved. Morbilliform rash followed by urticary were the most frequently observed reactions. Interestingly, over 50% of patients with massive edema –independent of etiology– died.

Conclusions. Intensive care unit patients are particularly at risk for developing an adverse cutaneous drug reaction.

Key words. Cutaneous drug reactions. Hospital epidemiology. Intensive care unit.

RESUMEN

Se realizó un estudio de cohorte en la Unidad de Terapia Intensiva (UTI) de un hospital de tercer nivel para evaluar la incidencia de reacciones cutáneas adversas a drogas. Se examinaron todos los pacientes internados en dicha unidad durante un periodo consecutivo de ocho meses. Observamos una incidencia de reacciones adversas a medicamentos de 11.6%. Los factores de riesgo asociados fueron sexo femenino, obesidad, edad mayor a 60 años y alteraciones inmu–nológicas (lupus eritematoso sistémico, distiroidismo y síndrome de antifosfolípido). Los antimicrobianos fueron los principales medicamentos involucrados. La erupción morbiliforme y la urticaria fueron las reacciones más frecuentes. Un hallazgo interesante fue que más de 50% de los pacientes con anasarca fallecieron. Concluimos que los pacientes internados en la UTI son particularmente susceptibles para desarrollar una reacción adversa cutánea a medicamentos.

Palabras clave. Farmacodermias. Epidemiología hospitalaría. Terapia intensiva.

INTRODUCTION

Adverse cutaneous drug reactions (ACDR) occur in approximately 2%–6% of all patients treated;1–6 morbilliform rashes represent the majority of ACDR (95%), followed by urticaria (5%).7–11 Although virtually any drug is capable of eliciting an adverse cutaneous reaction, the most frequently implicated agents are antimicrobials and non–steroidal anti–inflammatory drugs (NSAID)3,6,7,12–15 Although the latency period for presenting an ACDR is variable, most reactions appear within the first week of treatment.7 Thirty percent of patients hospitalized for over a month present at least one cutaneous reaction following drug administration2,16 and this results in longer hospital stay, greater cost, and almost twice the morbidity than for the rest of the hospitalized population. Severe ACDR were the fourth cause of death among hospitalized patients in the United States in 1994 and its incidence has remained stable during the last 30 years.10,11,17

The most frequent underlying predisposing factors for the presentation of ACDR are asthma,2,6,18 pregnancy,4,19 hepatic failure,20–22 renal failure,23–25 systemic lupus erythematosus,22 infection by Herpes Virus 6–7,23,26 AIDS,5,23 and other immune dysregulations.27,28

We designed a prospective study to evaluate the incidence and risk factors involved in cutaneous adverse drug reactions among ICU patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An observational, prospective cohort study from March 1st–October 31st 2003 at the general ICU of an adult tertiary care center was conducted. Prior approval by our Institutional Review Board, all patients were physically examined twice a day. A certified dermatologist clinically diagnosed cutaneous adverse drug reactions. All patients in the ICU were seen daily and the following were recorded: age, gender, number of days in the ICU, underlying diseases and administered drugs. In addition, the following were recorded in those who developed an ACDR: personal or familiar history of adverse reactions to drugs, dermatological diagnosis, evolution of the dermatosis, and patient follow–up. Suspicious drugs were chosen by their frequency in the literature.

All patients were followed until skin problem resolution, hospital discharge or death. Frequency, median, mean and mode were obtained with the SPSS program and the Epi Info 6.0 program was used to calculate odds ratio, p and  of the possible risk factors for presenting an ACDR.

of the possible risk factors for presenting an ACDR.

RESULTS

190 patients were hospitalized at the general ICU during our 8–month study period. ACDR occurred in 22 (11.6%), and of these, 45% were over 60, 36.3% were 40–60 years of age and 18.1% were 20–40 years old. No pediatric patients are seen at this Institution. Six (27%) developed the reaction within the first four days of hospitalization in the ICU. The majority of patients were females (n = 15; 68.2%). Mean duration of stay at the ICU was 4 days, 1.8 days more than patients without ACDR, which was statistically significant.

The most common underlying diagnosis were: dysthyroidism (hypo–hyperthyroidism) in 15 patients (68.18%), obesity in 12 (54.5%) patients (BMI >30), systemic lupus erythematosus in 11 patients (50%) and sepsis in 9 patients (40.9%). Patients with SLE or antiphospholipid antibodies syndrome were under corticosteroid treatment. Interestingly, 3 (50%) of the 6 patients with antiphospholipid antibodies syndrome developed ACDR. Other underlying diseases are shown in table 1. Diagnoses were taken from the patients' clinical records.

Most reactions (n = 18; 81.8%) were attributed to antimicrobials, mainly cephalosporins (33.3%), and the second most common offending drug group were NSAID (10 patients–45%); other drugs implicated were angiotensin converter enzyme inhibitors (ACE) administered to 7 (31.8%) patients and diuretics to 6 (27.2%) patients. Although anticonvulsant seizure drugs are commonly implicated in ACDR none of the 19 patients that received them presented an ACDR.

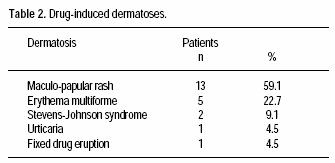

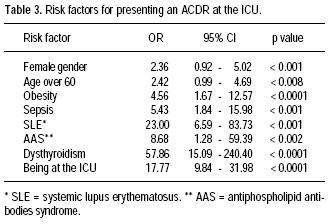

Seventeen patients (77%) had no previous personal or familiar history of ACDR. The most frequent ACDR seen was morbilliform rash (59%); other ACDR are shown in table 2. Odds ratio for risk factors associated to ACDR are shown in table 3.

One hundred and thirty patients (68.42%) had some degree of edema, of which 71 (54.61%) died.

Of the 168 patients that did not present an ACDR during their hospitalization at the ICU, 83 (49.4%) were females and 85 (50.5%) males. Forty–nine (29.16%) were between 20 and 40 years old, 96 (57.14%) between 40 and 60 years, and 23 (13.7%) over age 60.

These patients with no ACDR had several underlying diseases (see Table 1). Ninety–four (55.9%) were taking antimicrobials, 63 (37.5%) patients were taking NSAID, 36 (21.42%) patients were taking ACE and 61 patients (36.3%) were taking diuretics.

Twelve (7.14%) patients had previous personal of familiar history of adverse drug reactions.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of ACDR in ICU patients was 11.6% and most were attributed to antimicrobials and secondly to NSAID; a majority appeared within the first 4 days of hospitalization at the ICU and cleared 24–48 h after the suspicious drug was withdrawn.

The risk factors associated to the development of ACDR were female gender, age over 60, being hospitalized in the ICU, obesity, and immune dysregulations such as systemic lupus erythematosus, dysthyroidism, and antiphospholipid antibodies syndrome.

Immune dysregulation was an important risk factor for developing an ACDR; autoimmune conditions such as SLE, AAS, and dysthyroidism were the most prevalent underlying diseases in our population with ACDR. Only 3 patients with AIDS were hospitalized in the intensive care unit during the study period and none presented ACDR, though evidently no conclusions can be drawn.

Obesity was an important risk factor for drug interactions; over 50% of the patients with ACDR were obese (BMI >30). A decreased metabolism of isoform 3A4 is seen in obese patients, resulting in an indirect inhibition of CYP3A4, one of the isoenzymes of cytochrome P–450.29 This may predispose to more adverse drug reactions and drug interactions in obese patients than in non–obese ones.

According to a recently published study of ACDR during a 5–year period, the risk for developing an adverse cutaneous reaction to drugs in patients with a positive family history for these reactions is 14% compared to 1.2% for those without a family history.30 In our study only 23% of the patients with an ACDR had a positive personal or family history.

The frequency of adverse cutaneous reactions increases with age, being more common in patients over 60.30–32 They are 35% more frequent in women independent of age and are 50% more common in senescent hospitalized women. This is probably secondary to these patients' increased drug intake, particularly NSAID for arthritic pain and their greater longevity compared with men.27,33,34 The majority of our patients were females over 60 years of age.

A recent prospective cohort study at our Institution with 4785 non–ICU hospitalized patients found an incidence of ACDR of 0.7% (in press). We found a greater incidence of ACDR among ICU patients (11.6% vs. 0.7%), probably secondary to longer hospitalization, greater drug intake, and more severe illness. Also, hospitalization in the ICU implies many risk factors including an intrinsic "stress load" that probably alters immunity in itself.

An interesting finding was that over 60% of the patients in the ICU had massive edema, and more than half of these died. Anasarca in ICU patients can be multifactorial: heart or kidney failure, multiple organ failure or physician–induced. A drug is defined as any substance that affects the structure or functioning of a living organism;35 thus water, when administered by a physician for therapeutic purposes, can be considered a drug. We believe this finding warrants further investigation to determine if physician–induced edema is related to an increased mortality in the ICU. In any event, edema should be considered a cutaneous sign of poor prognosis independent of its etiology.

Also of interest for further investigation is the relationship between diabetes mellitus, hypertension and a low incidence of ACDR.

The skin, though frequently neglected in an ICU setting, is an important reflection of the patient's general health status. We consider there is a need for a pharmacological surveillance program of acute cutaneous reactions specifically in ICU patients.

REFERENCES

1. Breathnach SM. Adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. Clin Med 2002; 2: 15–9. [ Links ]

2. Beltrani VS. Cutaneous manifestations of adverse drug reactions. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 1998; 18: 867–95. [ Links ]

3. Cordoliani F. Eczemas. Rev Infirm 1988; 38: 29–32. [ Links ]

4. Lee A, Phil M, Pharm MR, Thomson J. Adverse drug reactions: Drug–induced skin reactions. Pharm Jour 1999; 262: 357–62. [ Links ]

5. Saiag P, Caumes E, Chosidow O, Revuz J, Roujeau JC. Drug–induced toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell syndrome) in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26: 567–74. [ Links ]

6. Vervloet D, Durham S. ABC of allergies: Adverse reactions to drugs. BMJ 1998; 316: 1511–4. [ Links ]

7. Bigby M. Rates of cutaneous reactions to drugs. Arch Dermatol 2001; 137: 765–70. [ Links ]

8. Sonntag MR, Zoppi M, Fritschy D, Maibach R, Stocker F, Sollberger J, et al. Exanthema during frequent use of antibiotics and antibacterial drugs (penicillin, especially aminopenicillin, cephalosporin and cotrimoxazole) as well as allopurinol. Results of the Berne Comprehensive Hospital Drug Monitoring Program. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1986; 116: 142–5. [ Links ]

9. Alanko K, Stubb S, Kauppinen K. Cutaneous drug reactions: clinical types and causative agents. A five–year survey of inpatients (1981–1985). Acta Derm Venereol 1989; 69: 223–6. [ Links ]

10. Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients. A meta–analysis of prospective studies. JAMA 1998; 279: 1200–5. [ Links ]

11. Lang DM, Alpern MB, Visintainer PF, Smith ST. Gender risk for anaphylactoid reaction to radiographic contrast media. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995; 95: 813–7. [ Links ]

12. Ramesh M, Pandit J, Parthasarathi G. Adverse drug reactions in a south Indian Hospital –their severity and cost involved. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safi 2003; 12: 687–92. [ Links ]

13. Reiner DM, Frishman WH, Luftshein S, Grossman M. Adverse cutaneous reactions from cardiovascular drug therapy. N Y State J Med 1992; 92: 137–47. [ Links ]

14. Jick H, Porter JB. Potentiation of ampicillin skin reaction by allopurinol or hyperuricemia. J Clin Pharmacol 1981; 21: 456–8. [ Links ]

15. Naldi L, Conforti A, Venegoni M, Troncón MG, Caputi A, Ghiotto E, et al. Cutaneous reactions to drugs: an analysis of spontaneous reports in four Italian regions. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 48: 839–46. [ Links ]

16. Litt J, Pawlak W, editors. Drug Eruption Reference Manual. New York: Parthenon Publishing Group; 1999. [ Links ]

17. Cluff LE, Thornton CF, Seidl LG. Studies on the epidemiology of adverse drug reactions. I. Method of surveillance. JAMA 1964; 188: 976–83. [ Links ]

18. McKinney PA, Alexander FE, Cartwright RA, Ricketts J. The Leukaemia Research Fund data collection survey: the incidence and geographical distribution of acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 1989; 3: 875–9. [ Links ]

19. Kurtz KM, Beatty TL, Adkinson NF Jr. Evidence for familial aggregations of immunologic drug reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 105: 184–5. [ Links ]

20. Shapiro LE, Shear NH. Mechanisms of drug reactions: the metabolic track. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1996; 15: 217–27. [ Links ]

21. Pullen H, Weight N, Murdoch JM. Hypersensitivity reactions to antibacterial drugs in infectious mononucleosis. Lancet 1967; 2: 1176–8. [ Links ]

22. Becker LC. Allergy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Johns Hopkins Med J 1973; 133: 38–44. [ Links ]

23. Dover JS, Johnson RA. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Part I. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127: 1383–91. [ Links ]

24. Wintroub BU, Stern RS. Cutaneous drug reactions: pathogenesis and clinical classification. J Am Acad Dermatol 1985; 13: 167–79. [ Links ]

25. Adkinson NF Jr. Risk factors for drug allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1984; 74: 567–72. [ Links ]

26. Yamanishi K, Okuno T, Shiraki K, Takahashi M, Kondo T, Asano Y, et al. Identification of human herpesvirus–6 as a causal agent for exanthema subitum. Lancet 1988; 1: 1065–7. [ Links ]

27. deShazo RD, Kemp SF. Allergic reactions to drugs and biologic agents. JAMA 1997; 278: 1895–906. [ Links ]

28. Kauppinen K, Stubb S. Drug eruptions: causative agents and clinical types. A series of in–patients during a 10–year–period. Acta Derm Venereol 1984; 64: 320–4. [ Links ]

29. Shapiro LE, Shear NH. Drug interactions: Proteins, pumps, and P–450s. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47: 467–84. [ Links ]

30. Asakura E, Mori K, Komori Y, Takano M, Hasegawa T, Kobayashi W, et al. The trend of the drug eruptions in the last fifteen years. Yakugaku Zasshi 2001; 121: 145–51. [ Links ]

31. Walker J, Wynne H. Review: the frequency and severity of adverse drug reactions in elderly people. Age Ageing 1994; 23: 255–9. [ Links ]

32. Bork K, editor. Cutaneous side effects of drugs. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1988. [ Links ]

33. Brawn LA, Castleden CM. Adverse drug reactions: an overview of special considerations in the management of the elderly patient. Drug Saf 1990; 5: 421–35. [ Links ]

34. Miller RR. Drug surveillance utilizing epidemiological methods: a report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. Am J Hasp Pharm 1973; 30: 584–92. [ Links ]

35. The Bantam Medical Dictionary. New York: Market House Books Ltd; 1990, p. 131. [ Links ]

Note: We have recently been advised that this project was chosen by the International Student Research Foundation as one of the five finalists among 396 International Research Projects.

Note: We have recently been advised that this project was chosen by the International Student Research Foundation as one of the five finalists among 396 International Research Projects.