Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista de investigación clínica

versión On-line ISSN 2564-8896versión impresa ISSN 0034-8376

Rev. invest. clín. vol.57 no.3 Ciudad de México may./jun. 2005

Artículo original

The impact of losartan on the lifetime incidence of ESRD and costs in Mexico

El impacto del losartan en la incidencia de por vida de la enfermedad renal de la etapa terminal y sus costos en México

Armando Arredondo,* Thomas A. Burke,*** George W. Carides,** Edith Lemus,**** Julio Querol****

* National Institute of Public Health, Cuernavaca, Mexico.

** Merck & Co., Inc., Blue Bell, PA, USA.

*** Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA.

**** Outcomes Research, MSD Mexico.

Correspondence and reprint request:

Dr. Armando Arredondo

Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública

Av. Universidad No. 655 Col. Sta. María Ahuacatitlán

62508, Cuernavaca, Mor.

Tel.: 01777 329–3062

Correo electrónico: aarredon@insp.mx

Recibido el 14 de diciembre de 2004.

Aceptado el 15 de marzo de 2005.

ABSTRACT

Background. The RENAAL (Reduction of Endpoints in Type 2 Diabetes with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan) study demonstrated that treatment with losartan reduced the risk of ESRD by 29% among hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy. The objective of this study was to project the effect of losartan compared to placebo on the lifetime incidence of ESRD and associated costs from a third–party payer perspective in Mexico.

Methods. A competing risks method was used to estimate lifetime incidence of ESRD, while accounting for the risk of death without ESRD. The cost associated with ESRD was estimated by combining the cumulative incidence of ESRD with the lifetime cost associated with ESRD. Total cost was estimated as the sum of the cost associated with ESRD from the three main public institutions in Mexico, the lifetime cost of losartan therapy, and other costs (non–ESRD/non–losartan) expected for patients with type 2 diabetes. Survival was estimated by weighting the life expectancies with and without ESRD by the cumulative risk of ESRD.

Results. The projected lifetime incidence of ESRD for losartan patients was lower (66%) compared with placebo patients (83%). This reduction in ESRD resulted in a decrease in ESRD–related cost of M$49,737 per patient and a discounted gain of 0.697 life years per patient. After accounting for the cost of losartan and the additional cost associated with greater survival, we projected that treatment with losartan would result in a net savings of M$24,073 per patient.

Conclusion. Treatment with losartan in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy not only reduced the within–trial incidence of ESRD but is projected to result in lifetime reductions in ESRD, increased survival, and overall cost savings to public institutions in Mexico.

Key words. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Losartan. Angiotensin II receptor antagonist. End–stage renal disease. Cost. Economics. Cost–effectiveness.

RESUMEN

Antecedentes. El estudio RENAAL (Reducción de los grados o puntos terminales en la diabetes tipo 2 con losartan, el antagonista de la anglotenslna II) demostró que el tratamiento con losartan redujo el riesgo de la ESRD (enfermedad renal de la etapa terminal) en 29% entre pacientes hipertensos con diabetes tipo 2 y neuropatía diabética. El propósito estudiado fue hacer una proyección del efecto del losartan comparándolo con el placebo en la incidencia de por vida de la ESRD y con los costos asociados de un tercer pagador en perspectiva en México.

Métodos. Se utilizó un método de riesgos muy competitivo para calcular la incidencia de por vida de la ESRD, al mismo tiempo que se calculaba el riesgo de muerte sin la ESRD. El costo asociado con la ESRD se calculó confirmando la incidencia acumulativa de la ESRD en relación con el costo de por vida de la terapia con losar–tan y otros costos (sin ESRD o sin losartan) con los que se contaba para pacientes con diabetes tipo 2. La supervivencia se calculó esperando las expectativas de vida con y sin ESRD por el riesgo acumulativo de ESRD.

Resultados. La proyectada incidencia de por vida de la ESRD en cuanto a los pacientes con losartan fue más baja (66%) comparada con los pacientes que tomaron placebo (83%). Esta reducción de la ESRD tuvo por resultado una disminución en el costo relacionado con la ESRD de $49,737 por paciente y una ganancia descartada de 0.697 años de vida por paciente. Luego de contabilizar el costo del losartan y el costo añadido asociado con una mayor supervivencia, llegamos a la conclusión de que el tratamiento con losartan daría por resultado un ahorro neto de $24,073 por paciente.

Conclusión. El tratamiento mediante losartan en pacientes aquejados de diabetes tipo 2 y neuropatía no sólo redujo la incidencia intraexperimental de la ESRD, sino que además nos ha servido para proyectar que resulte en reducciones de por vida en la ESRD, en una supervivencia incrementada y en un ahorro total de costos en cuanto a las instituciones públicas en nuestro país.

Palabras clave. Diabetes mellítus tipo 2. Losartan. Receptor antagonista de la angíotensína II Enfermedad renal de la etapa terminal. Costo. Economía. Efectividad de costos.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is considered to be the leading cause of end–stage renal disease (ESRD) in Mexico.1,3 There are an estimated 25,000 patients currently receiving chronic dialysis in Mexico, with the majority receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis.4 While dialysis services are unrestricted in the private sector in Mexico, there are limitations to the use of dialysis services used by salaried workers in the formal economy (40% of population), and severe restrictions in the economically disadvantaged population using services from the Health Secretariat (45% of population). It is anticipated the pressures for the use of dialysis services will continue to grow. The number of individuals receiving dialysis in Mexico is estimated to triple (to 75,000) by the year 2010,5 and the management of ESRD will continue to represent a challenge for the economically limited health institutions within Mexico. Healthcare programs aimed at preventing the onset of ESRD have the potential to substantially reduce the economic burden of ESRD in Mexico.

The RENAAL (Reduction of Endpoints in Type 2 Diabetes with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan) Study demonstrated that in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy, treatment with losartan compared with non–ACEI conventional antihypertensive therapy (CT) reduced the incidence of the primary composite endpoint of doubling of the serum creatinine concentration, ESRD, or death by 16% (p = 0.022), and reduced the risk of ESRD alone by 29% (p = 0.002).6 A within–trial economic evaluation of the RENAAL Study from a US payer perspective showed a reduction of 33.6 days with ESRD with an associated reduction of $5,144 (p = 0.003) in ESRD–related costs per randomized patient over 3.5 years. After factoring in the drug cost of losartan, this reduction in ESRD days resulted in a net savings of $3,522 per randomized patient over 3.5 years. These cost savings were observed to increase at the 4–year follow–up — $7,058 ESRD–related cost savings and $5,298 net savings.7 In this paper, the within–trial economic evaluation is extended by projecting the effect of losartan compared to CT on lifetime cumulative incidence of ESRD and associated costs. The perspective is the public institutions in Mexico, namely those representing salaried workers in the formal economy (IMSS and ISSSTE), and the economically disadvantaged population which relies on services of the Ministry of Health.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Study design

The RENAAL Study design and results have been reported in detail by Brenner et al.6 In brief, RENAAL was a multinational, double–blind, randomized, placebo–controlled clinical trial designed to evaluate the renoprotective effects of losartan in 1,513 patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. Patients were randomized to losartan or placebo on a background of non–ACEI conventional antihypertensive therapy (e.g., diuretics, calcium–channel antagonists, alpha–or beta–blockers, centrally acting agents, or some combination of these types of medications) . Patients enrolled had type 2 diabetes and a urinary albumin: creatinine ratio of at least 300 mg/g on a first morning specimen and serum creatinine between 1.3 and 3.0 mg/dL. Ninety–seven percent of patients were either receiving antihypertensive therapy or were noted to have hypertension but were not receiving antihypertensive therapy at baseline. The RENAAL population was, on average, 60 years of age, 63% male, and 18% Hispanic.6 The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each center, and all patients gave written informed consent. The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of the time to first event of doubling of serum creatinine, ESRD, or death.

Statistical methods

• Cumulative Incidence of ESRD. We estimated the lifetime cumulative incidence of ESRD using a variation of the cumulative incidence competing risk method.8 This approach accounts for the possibility that a patient may die prior to requiring dialysis or transplantation. There are two components to this estimate. The first component is the hazard (risk) function for ESRD conditional on ESRD–free survival. This component measures the risk that a patient experiences ESRD at time t given that the patient has survived up to time t without ESRD. To determine the best estimate for this component we fit several parametric survival models to the RENAAL trial data on ESRD. These models included the Weibull, log–logistic, log–normal, and exponential.9 The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to determine the best fitting model.10 The AIC criterion is a commonly used measure of the goodness of model fit with smaller values indicating better fit than larger values. The AIC was lowest (best) for the Weibull model, which we therefore chose as our model for ESRD conditional on ESRD–free survival. However, because a diagnostic plot suggested non–proportional hazards, we fit completely separate Weibull models for losartan and placebo. The second component to the cumulative incidence of ESRD is the ESRD–free survival function. This function measures the probability that a patient survives to time t without ESRD. To determine the best estimate for this component we again fit the same type of parametric survival models to the RENAAL trial data on ESRD and all–cause death. The AIC was lowest (best) for the Weibull model, which we therefore chose as our model for ESRD–free survival.

We then multiplied these two components (one) risk for ESRD conditional on ESRD–free survival, and (two) ESRD–free survival, and summed the products over time to obtain the lifetime cumulative incidence of ESRD.

Lifetime Survival. Life expectancy by treatment group was estimated by weighting the life expectancies with and without ESRD by the treatment specific lifetime probabilities of ESRD. Life years gained by preventing ESRD was estimated by taking the difference between life expectancy for patients without ESRD and life expectancy for patients with ESRD. These life expectancies were estimated with Weibull models applied to the RENAAL data.

ESRD–Related Costs. The lifetime mean cost associated with ESRD was estimated by multiplying the discounted (3%) cumulative incidence of ESRD by the discounted (3%) lifetime cost attributable to ESRD. ESRD costs consisted of the costs of dialysis obtained from the three most important public institutions in Mexico: the Ministry of Health or (Secretaria de Salud, SSA), the Mexican Social Security Institute (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, IMSS), and the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado, ISSSTE). The daily cost of dialysis at these institutions, weighted by the proportion using peritoneal vs. hemodialysis, was M$207, M$252, and M$223, at SSA, IMSS, and ISSSTE, respectively.11 The cost estimated included quantitative and qualitative differences between all inputs required to provide health care in each intervention. Before the estimation of average cost by intervention, unit costs were estimated using five categories: human resources –medical personal–, infrastructure, training for a patient relative, the average number of HD or PD, and general services. A single cost was then determined by taking an average of costs at the three institutions (M$227 per day). We applied the average daily cost to the life expectancy following dialysis, which we estimated based on survival data for diabetics started on dialysis in Mexico (forth years).

Total cost. Total cost was defined as the sum of the cost attributable to ESRD, the cost of losartan therapy, and additional costs expected for patients with type 2 diabetes but not related to ESRD treatment or study medication (M$18.54/day).12 The cost of losartan was estimated based on the price of losartan for public institutions, the overall within–trial usage of losartan by dose, and projected lifetime survival (see above). The 2004 price of losartan for public institutions in Mexico was M$ 11.59 for both the 50 mg and 100 mg tablets. We assumed that patients who discontinued study therapy incurred no additional medication costs. Given that there were no differences in the incidence of side effects between treatment groups,6 we assumed that the difference in the cost of side effects between treatment groups was zero. We also conservatively assumed that there were no differences in the cost of non–study medications between treatment groups as there was a small but not significantly greater use of non–study medications in the placebo group.6

To estimate costs, we adopted the perspective of a healthcare system responsible for all direct medical costs. All randomized participants were included in the analysis on an intention–to–treat basis. The bootstrap method13 was used to construct 95% confidence intervals on treatment differences. All costs were discounted at an annual rate of 3% and are reported in 2004 Mexican pesos. The costs estimation was adjusted to the inflation applying an econometric adjustment factor to control inflation rates according to the 2004 prices index to the consumer in Mexico. It was also validated translating Mexican pesos to US dollars with June–2004 as a reference period.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted several sensitivity analyses, including a 50% reduction in ESRD costs, confining losartan drug costs and ESRD reductions to the within–trial period, and accounting for all lifetime losartan drug costs while confining ESRD reductions to the within–trial period.

RESULTS

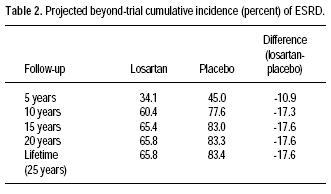

The projected cumulative incidence of ESRD beyond the RENAAL trial period is shown in table 2. Figure 1 shows these estimates coupled with the within–trial cumulative incidences reported in Gerth, et al.14 The addition of losartan therapy to the treatment regimens of persons with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and nephropathy is estimated to result in a reduction in the lifetime cumulative incidence of ESRD from 83 to 66%. In turn we projected an absolute reduction in ESRD incidence of 16% (83–66%) and an NNT (number needed to treat) of 6 (1/0.16) to prevent one case of ESRD over a lifetime.

Table 3 summarizes the results for lifetime cost, cumulative incidence of ESRD, and life years saved. The majority of patients (71%) received the 100 mg per day dosage of losartan within the trial period.6 Lifetime losartan study medication cost was estimated to be M$20,275 per patient. In addition, losartan patients were projected to incur an additional M$5,388 of cost due to increased life expectancy. However, losartan reduced ESRD–related cost per patient by M$49,737 as compared with placebo due to a lower lifetime cumulative incidence of ESRD for losartan as compared with placebo. Thus, losartan treatment reduced total cost by M$24,073. We estimated that patients without ESRD would have a discounted (3%) life expectancy of 8.8 years whereas patients with ESRD would have a discounted life expectancy of 4.3 years. The difference, 4.4 years, is the expected life years gained by preventing ESRD. By taking the product of the discounted absolute risk reduction for ESRD, 0.157, and the discounted expected life years gained by preventing ESRD, 4.44 years, we obtain an estimate of 0.697 life years gained for losartan.

Sensitivity analyses

Table 4 shows the results of the sensitivity analyses. The cost of ESRD could be decreased by as much as 45% and losartan treatment would still be cost saving. A 50% reduction in ESRD costs would result in an added cost per patient of M$ 1125 and an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of M$ 1614. If we do not project additional reductions in ESRD incidence for losartan patients beyond the trial and account only for the losartan drug cost incurred within the trial, the net cost savings would be M$ 10,087. If we do not project additional reductions in ESRD incidence beyond the trial but include all beyond–trial losartan drug cost, the net cost savings would be 1447.

DISCUSSION

The results from this study suggest that the benefits observed during the RENAAL trial continue to grow during the beyond trial period. In particular, the lifetime projections indicate that the beyond–trial incidence of ESRD grows at a slower pace in the losartan + CT treated group as compared with the placebo + CT treated group. By delaying the need for dialysis, patients eventually die of other causes such as cardiovascular disease and thus never require renal replacement therapy.

This economic evaluation, which incorporates clinical, epidemiological and cost inputs, constitutes an evidenced–based approach to health policy and planning in the context of health care reform in middle income countries like Mexico. As the epidemiological transition further progresses from infectious to chronic or degenerative disease in Mexico, so will the health care demand for diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and ESRD and the need to identify effective disease prevention strategies. Gerth et al. recently estimated that there are 175,729 persons in Mexico with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy (urine albumin/creatinine > 300 mg/g).15 If the lifetime benefits of losartan were similar to those projected here from RENAAL, we might expect that lifetime losartan treatment would reduce the number of persons developing ESRD of their lifetime by 30,928. This reduction in ESRD would translate into an M$8,740 million (M$8.74 billion) reduction in the cost of ESRD and M$4,230 million (M$4.23 billion) in net savings, based on the lifetime projection. These freed resources may be used to extend dialysis treatment to those who may not have otherwise qualified.

A potential limitation of this study is the use of the four years of within–trial data to project outcomes and costs beyond the trial. However, many medical interventions for chronic conditions have an impact on costs, and outcomes which extend over a patient's lifetime. In these instances, a life time horizon may be the most appropriate time horizon for clinical and cost effectiveness. In addition, such a time horizon is required to quantify the implications of any differential mortality effect between alternative technologies.16

Another possible issue that may be raised is whether our model of ESRD incidence may have overestimated the reduction in the lifetime cumulative incidence of ESRD for losartan and thereby overestimated the reduction in cost. To address this issue, we conducted sensitivity analyses which accounted for the lifetime ESRD–related costs for patients experiencing ESRD within the trial, but did not project additional reductions in ESRD beyond the trial. Within the sensitivity analysis, it was observed that even in the absence of a continued beyond trial treatment benefit, the results show that losartan resulted in net cost savings.

It should be recognized that the ESRD incidence results from this evaluation are being applied to a setting, clinical practice in Mexico, which is quite different from the clinical trial setting of RENAAL. The cumulative incidence of ESRD in clinical practice in Mexico may differ from that reported here; however, in the absence of epidemiological data from Mexico on the cumulative incidence of ESRD, it is difficult to predict the direction of this bias.

Finally, a trial similar to RENAAL, comparing losartan plus conventional antihypertensive therapy (calcium–channel antagonists, diuretics, alpha–blockers, beta–blockers, and centrally acting agents) regimen to conventional antihypertensive therapy plus placebo regimen would no longer be ethical based on the conclusive benefit of losartan in terms of reducing the risk of doubling of serum creatinine, end stage renal disease, or death. The conducted of any randomized trial requires uncertainty by the trial investigators, and the scientific community as a whole, in terms of the relative benefits of the randomized therapies. However, given the paper's focus on health economics this issue is beyond the present analysis.

In summary, in patients with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and nephropathy, losartan is projected to reduce the cumulative incidence of ESRD, resulting in an NNT to prevent one case of ESRD of 6. This reduction in ESRD incidence is estimated to reduce the costs of ESRD by M$49,737 per patient and to increase life expectancy by 0.99 years (0.70 discounted) . After accounting for the cost of losartan and the cost associated with greater survival, the reduction in ESRD would result in a net saving of M$24,073 per patient. Treatment with losartan in patients with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and nephropathy can result in substantial lifetime reductions in ESRD and associated costs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was funded by Merck & Co., Inc.

REFERENCES

1. García PM, et al. Las múltiples facetas de la investigación en Salud. México, DF. IMSS; 2001, pp. 153–70. [ Links ]

2. Keane H. Advances in slowing the progress of diabetic nephropathy. Patient Care 2001; 30: 28–41. [ Links ]

3. Rodríguez Moctezuma. Características epidemiológicas de pacientes con diabetes–IRC en el Estado de México. Rev Med IMSS 2003; 41(5): 383–59. [ Links ]

4. Brien H, Garcia H, Garcia G, et al. Epidemiología de la insuficiencia renal crónica en Jalisco. Boletín Colegio Jalisciense Nefrología 2001; 5: 6–8. [ Links ]

5. Cueto–Manzano AM. Peritoneal dialysis in Mexico. Kidney International 2003; 63(Supl. 83): S90–S92. [ Links ]

6. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, De Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 861–9. [ Links ]

7. Herman WH, Shahinfar S, Carides GW, et al. Losartan reduces the costs associated with diabetic end–stage renal disease. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(3): 683–7. [ Links ]

8. Kalbfleish JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York: Wiley, 1980. [ Links ]

9. Lawless JF. Statistical Models and Methods for Lifetime Data. New York: Wiley, 1982. [ Links ]

10. Akaike H. Information Theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: 2nd International Symposium of Information Theory and Control. EBN Petrov and F Csaki (Eds.). Budapest: Akademia Kiado; 1973, pp. 267–81. [ Links ]

11. Arredondo A. Costs for health care interventions in Mexican Health System. Mexico: National Institute of Public Health; 2004. [ Links ]

12. Arredondo A. Financial requirements for health services demands for diabetes and hypertension in Mexico: 2001–2003. Rev Invest Clin 2001; 53(5): 422–9. [ Links ]

13. Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [ Links ]

14. Gerth WC, Remuzzi G, Viberti G, et al. Losartan reduces the burden and cost of ESRD: Public health implications from the RENAAL study for the European Union. Kidney International 2002; 62(Suppl. 82): S68–S72. [ Links ]

15. Gerth WC, Ribeiro AB, Ferder LF, et al. Losartan reduces the burden of end–stage renal disease: Public Health Implications from the RENAAL Study for Latin America. Sociedad Iberoamericana de Información Científica (SIIC). In Press. [ Links ]

16. UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. UK National Health Service; 2004. [ Links ]