Introduction

Since his initial studies, Freidson1 pointed out that medicine, as a profession, is founded on an autonomy that is guaranteed and recognized by the State, which leads to the creation of a sort of monopoly, as a result of the recognition of the benefits this contributes with. This social contract is granted in exchange for professionalism and an ethical behavior that comprises empathy, compassion, honesty, integrity, altruism, and professional excellence.

In the last decades, professional autonomy has constantly been limited because highly hierarchical bureaucratic organizations that seek to control costs or increase profits are involved.1 The practice of medicine has been subjected to all kinds of directives, guidelines, protocols and standards adopted from production processes, to the detriment of the relationship with the patient.2,3 This situation has led to a distancing from the expectations of individuals, families and communities, which, far from promoting a sense of service, ignores social needs.

Despite the above, medical schools’ social contract indicates that these institutions have the responsibility to influence the changes in the health care system, in order for it to evolve into an effective, efficient, accessible, equitable and sustainable model. To achieve this, medical education principles consistent with the statements of the World Health Organization4 and the General Consensus for Social Accountability of Medical Schools were formulated.5 The COVID-19 pandemic constitutes a direct challenge to these premises wich, although they have evolved through the years, today they are obsolete and insufficient.6

Medical schools current social accountability

The World Health Organization defines medical schools social accountability as the obligation to direct their educational, research and service activities to the solution of priority health problems in the place where they are to provide services.4 This need became evident when it was verified that various medical schools obtained low scores in their relationships with society.7

In the same line of thought, the Global Consensus for Social Accountability (GCSA) of Medical Schools states that medical schools must respond to current and future health needs, redirect their educational and research priorities, strengthen their association with stakeholders and use performance-based certification.4 Part of these responsibilities are fulfilled with the training of health professionals based on a structure derived from the Flexner Report, which has been accepted for decades.8

Medical education basic principles

The dominant model in medical education is organized around four basic principles, which are insufficient in current COVID-19 pandemic conditions (Table 1).

Table 1 Principles of medical education where challenges unveiled by the COVID-19 pandemic are faced

| Principles of medical education | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Concentration of training at higher levels of the health system | The emergency requires prevention and patient management at home. The hospital is no longer a propitious environment for patient treatment and teaching. |

| Segmentation and disaggregation of components | The virus affects multiple organs and levels of organization. Comorbidities and lack of definition require coordinated action of several clinical departments, including their multifunctionality. |

| Patient homogeneity | There are no single patterns in the evolution of the disease. |

| Centralized generation of knowledge | The research agenda includes areas that have not been of great interest to academic researchers, such as basic science and public health. |

First principle: concentration of training at the higher levels of the health system

Since the Flexner Report, a curricular structure that establishes science teaching followed by clinical learning has been perpetuated; a first stage of learning about biomedical content and then teaching in hospitals at patient bedside.9 This contradicts GCSA-established directions: “the medical school acknowledges that a sound health system must be founded on a solid primary health care approach.”5 Recent studies show that home-based medical care has better clinical outcomes, especially in patients with comorbidities;10 however, students exceptionally dedicate time to home-based medical care interventions or at schools and work centers.

Challenge 1. COVID-19 emergence has required intra-domiciliary care through telemedicine, community-based paramedicine and virtual care services.11 Correct management involves remote medical counseling, testing for early detection of symptoms, and even using capillary oxygenation monitoring to prevent patient complications and hospitalization.12,13 To the above, prevention, education of communities, isolation of cases and follow-up of contacts must be added as the axis of the health system, where the hospital should only be a support mechanism.

Second principle: segmentation and disaggregation of components

Flexner’s proposal postulates a scientific medicine that guides one-way and linear clinical practice.14 Future physicians are trained on reductionist guidance, which breaks people down into parts to locate faults and correct them. This disciplinary tradition creates difficulties for curricular integration.15 Medical students learn independent contents and practices, which they experience in isolation and uncoordinately in clinical departments, under the concept of privileging immediate causality.

Challenge 2. The linear paradigm is in crisis, since knowledge is generated both in the laboratory and in clinical practice, according to the concept of translational medicine.16 COVID-19 acts at all levels of organization: molecular, cellular, and on organs and systems, which requires an approach by interdisciplinary and multifunctional teams.17 The emergency requires the articulation of experts from different levels of care in order to empower community-based action.18

Third principle: patient homogeneity

Students are educated in the paradigm that all patients respond the same way to the same diseases and should treated the same way. This approach has been named by Montori3 “industrialized medicine”, because it acts with parameters that are characteristic of manufacturing production. This orientation implies ignoring the context and avoiding adaptation to the specific case. Berwick19 has demonstrated the harm that can result from eliminating said variations.

Challenge 3. A person with COVID-19 can be without manifestations or develop complex molecular phenomena such as inflammation, cytokine storm and intravascular coagulation, until culminating in multiple organ failure.12 Uncertainty and diversity offer greater learning opportunities, such as those based on challenges.20,21

Fourth principle: centralized generation of knowledge

Academic centers capable of research are centralized and articulated with the leading biomedical-industrial complex that directs medical research in the world. Students are only trained to locate, read, and value the quality of a research article.22 This reality lacks methodological training and opportunities to conduct research or make innovations to improve the quality of care.23

Challenge 4. Each member of the academic community is learning about SARS-CoV-2 from multiple sources, where they can investigate from the molecular biology of the virus, the pathophysiology, the usefulness of drugs, clinical management or preventive measures.24 Currently, research can be carried out at all three levels of care and in a decentralized way in multiple countries and international groups, thanks to advances in computing. Other forms of rapid publication such as preprints, to which the scientific community has immediate and free access, are gaining relevance.25

Graduates’ traditional profile

Since the year 2000, several countries and international medical education bodies have strived to establish the competencies of the modern physician.26,27 However, this competency design work was carried out under a different assumption than the world that today is collapsing due to the pandemic. The change is so radical that some point to two different eras, before and after COVID-19, B. C. and A. C. by their acronyms.28,29

Given this new scenario, it should be questioned whether medical competencies are sufficient for the so-called new normality. For this analysis, the competencies of the Mexican general practitioner established by the Association of Faculties and Schools of Medicine (AMFEM – Asociación de Facultades y Escuelas de Medicina) are used:30

1. Mastery of general medical care.

2. Mastery of scientific bases of medicine.

3. Methodological and instrumental capacity in science and humanities.

4. Ethical and professionalism mastery.

5. Mastery of medical care quality.

6. Mastery of community care.

7. Capacity to participate in the health system.

This conceptualization is consistent with the competencies established in European countries and by medical associations, and therefore represents the thinking and meaning of medicine of those who were trained in past decades.26 When reviewing these competencies, it stands out that patient health, safety and expectations are privileged, ignoring the physician in training as a person. When contrasting them with the GCSA principles, it is identified that there is consistency regarding the individual-family-community approach, health promotion, health education, prevention and specific protection from diseases, epidemiological approach and care for human rights, among others.30

However, in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for a new competency that considers the student as a person with needs and expectations becomes evident.*31-32 This perspective is partially included in the competency called “ethical and professional mastery”, where the “commitment to oneself” section is identified, which focuses on reflection and personal analysis.30

This biased vision of exclusive benefit to society has been interpreted as heroism, servility and charity, which has had an impact in the form of infections, suicides, freedom of conscience limitations, and even sarcasm for aspiring to a decent remuneration for the provided services.33,34 Students themselves lack a patient-centered vision due to the constant threat to their professional identity.35 The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for training in the following aspects: emotional strength, self-protection against risks inherent to the profession and self-care of personal health and own economy.34

Medical schools new social function after the pandemic

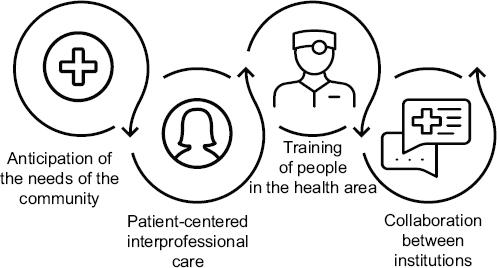

Social accountability is redirected and re-conceptualized in the face of the COVID-19 contingency. A model is proposed that reflects the functions of anticipating community needs, interprofessional, patient-centered care, training of people in the health area, and collaboration between institutions (Fig. 1).

Clithero-Eridon, Albright, and Ross36 find that –from the perspective of medical students, mentors and physicians– social accountability primarily means serving the community by ensuring health and well-being. For years, the hospital has been identified as the most important learning scenario for medical schools; however, according to Woolliscrof,37 maybe it’s time to consider “home-based hospital” and virtual communication as effective and efficient resources for clinical care and education. The pandemic is demanding continuous learning, creatively acting in the face of the uncertain and unknown, as well as critically evaluating one’s own performance.38

The new models need to be structured from patient- and community-centered reality, with a comprehensive and personalized approach.39 Stratification of disciplines and professions is blurred along with the line that divides the borders of knowledge between them. Inter-professional education becomes a fundamental need in order to collaborate in environments of uncertainty.40 This type of teaching and collaboration allows team members to make decisions as equals to ensure the quality and safety of clinical care.41 Inter-professional intervention becomes an opportunity to find new strategies for the treatment of patients with COVID-19.18

Regarding the social function of training health professionals, it is essential to add a competency: mastery of self-protection and self-care of the person, where the person can be the patient, the student, the teacher or the doctor (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Model of competencies for the Mexican General Practitioner adapted from the Association of Medical Faculties and Schools model.30

The institution’s commitment must be extended towards educational programs that guarantee safety, physical integrity, health, freedom, professional development, prestige, dignity, care of emotions, autonomy and relationships.26 According to Kofman42, a conscious endeavor is that with awareness of both the inner and outer world. This implies caring for society without neglecting the academic community. Current educational programs for health professionals are being insufficient to address a multifactorial reality in the new complex paradigm.43 The only constant fact in recent years is uncertainty, chance, indeterminacy and emergency, which becomes tangible with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Professionals of the present and the future must be trained to face adversities in a creative and innovative way. The health emergency has led to the use previously little-explored innovations such as long-distance clinical care, determination of diagnoses and therapeutic interventions with advanced techniques and virtual education, which is transforming the way to conceptualize medical education.37,44,45

COVID-19 has demonstrated the inability to make educational programs converge with health systems. There is an imperative need to serve the communities from medical schools through open collaborative models between institutions, including higher education, the health sector, private initiative and government.5 According to Boelen, Dharamsi, and Gibbs,46 the socially accountable medical school works in this association in order to impact on people’s health and demonstrates it with relevant, high-quality results. Torre47 warns on the need for convergence of public and private sectors to meet biological health needs and, in addition, economic needs, which are increasing as the pandemic progresses.

Conclusion

As a new era advances towards patient-centered care, the need for the country’s medical schools to articulate and explain public perceptions and their internal and external obligations becomes evident. Medical schools must stop self-conceptualizing under linear and isolated schemes in order to move to flexible, integrated and active structures, towards a transformation that has a direct impact on everyone’s health.

Institution leaders must involve the academic community and other stakeholders in society in the planning and accelerated execution of policies, programs and interventions that initiate a new A.C. health system and medical education. Leaders must do it now, simply because it is the right thing to do.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)