Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought not only the risk of transmission and infection-related death, but also important psychological effects.1 Psychological factors are known to play a vital role in the success of public health strategies that are used to control epidemics and pandemics, as well as in the communication of risks, vaccination and antiviral therapy, hygiene practices and social distancing.2-4

Pandemics, such as that of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), have been reported to be stressful situations that threaten physical health and psychological well-being, in addition to causing disruptions in interpersonal functioning and the perception that transmission is relatively uncontrollable even when measures that reduce the risk are taken (for example, wearing masks, avoiding crowds).5

In viral outbreaks, a person with severe anxiety can misinterpret benign muscle aches or cough as signs of infection, as well as developing maladaptive behaviors such as compulsive handwashing, social withdrawal and panic shopping, which can have negative consequences for the individual and his/her community. For example, a sense of urgency for products that are needed for quarantine can lead to overspending in the storage of resources and harm to the community, which needs such resources for other purposes, including medical care.3 On the other hand, people who consider themselves to be at low risk of infection are unlikely to change their behavior and follow the social distancing recommendations, with the consequent negative impact on efforts to mitigate the dissemination of the virus.

With regard to reported psychological symptoms, mild anxiety was identified in 21.3 % of 7143 college students exposed to COVID-19; in 2.7 %, moderate anxiety, and in 0.9 %, severe anxiety. Living in urban areas and with the parents were protective factors against anxiety. Having relatives or acquaintances infected with COVID-19, unstable financial situation and backlog in academic activities were associated with higher anxiety (p < 0.001). Social support was negatively correlated with the level of anxiety (p < 0.001).1

Moderate to severe or severe anxiety and/or depression symptoms were identified in 35 % of 180 SARS survivors one month after recovery. Health workers or those who had relatives who died because of SARS were more likely to develop high levels of distress.6

When hospital health workers (n = 82) were compared during the peak of the epidemic with hospital staff who recovered from SARS (n = 97), both groups were found to have the same level of concern about infecting others (especially their family members). Workers were more afraid of infection; in survivors, SARS-related fear was correlated with post-traumatic stress symptoms; in addition, they expressed concern about other health problems and discrimination (p < 0.05).7 People who have experienced public health emergencies have varying degrees of stress, even after the event has ended or they have recovered and been discharged from hospital.6,8

Taking into account social interaction restrictions and confinement measures, mental health services have adopted the use of hotlines, mobile application platforms, the internet and social networks to share strategies for dealing with stress,9 as well as for assessing the psychosocial impact on exposed population. Therefore, the purpose of this research was to determine the levels of anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as self-care behaviors, during the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population.

Method

A non-experimental, cross-sectional study was carried out,10 for which an online survey was conducted using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling; 1508 male and female participants from Mexico and abroad were included. As inclusion criteria, a minimum age of 12 years and knowing how to read and write were considered. Individuals with cognitive impairment that prevented them from answering the survey were excluded, and those who during or after completing the survey decided not to continue participating were removed from the investigation.

An identification card was designed, which included sociodemographic and clinical data. The following evaluation instruments were used:

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), developed by Kroenke et al. in 2001,11 is a screening tool that assesses the possible presence of major depressive disorder and the severity of depression symptoms. Its structure is one-dimensional, it has nine items based on Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition, Text Revision (DSM IV TR) criteria and a global Cronbachs alpha of 0.89. It was validated in the Mexican population,*1 with an internal consistency of 0.86 and an explained variance of 47 %.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Scale (GAD-7). Developed by Spitzer et al. in 2006,12 it is a screening tool that assesses the presence of possible generalized anxiety disorder. It has a one-dimensional structure of seven items based on DSM IV TR criteria, which explain 63 % of variance, and a global Cronbachs alpha of 0.92. It was validated in the Mexican population,* with an internal consistency of 0.88 and an explained variance of 57.72 %.

Self-care behaviors visual analogue scale. Behaviors were assessed using a 10-point visual analogue scale, where 0 means I do not follow the recommendation at all and 10 means I follow the recommendation all the time, which specify how individuals carried out self-care strategies.

Sample collection was carried out from March 26 to April 12, 2020. The purpose of the investigation, its procedure, data confidentiality, as well possible risks and benefits, were explained to each participant by electronic means. All individuals voluntarily participated and granted written consent. The procedures of this investigation complied with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki with regard to research in human subjects.

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 22.0. Descriptive analysis of central tendency and dispersion measures was carried out to illustrate demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as univariate analysis to identify the differences between sociodemographic variables and the level of anxiety and depression symptoms. Normality of variables was determined by means of Kolmogorov-Smirnov goodness-of-fit test (p < 0.001), whereby a non-normal distribution was observed; therefore, medians and non-parametric Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used.13 Finally, Pearsons correlation analysis was carried out. A p-value < 0.05 was established as statistically significant.

Results

As it can be observed in Table 1, total sample consisted of 1508 participants, 1,123 women and 385 men, with an average age of 34 years; 61.3 % were childless, 50.8 % were single, 55.2 % had a college degree, 35.6 % worked as professionals and 24 % referred having some chronic degenerative disease.

Table 1 Characteristics of the surveyed individuals with regard to symptoms of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 1508)

| Age (years) | Mean = 34.46; range 18-82 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Level of education | ||||

| Females | 1123 | 74.5 | Basic education | 34 | 2.3 |

| Males | 385 | 25.5 | High school | 209 | 13.9 |

| Country | College degree | 833 | 55.2 | ||

| Mexico | 1421 | 94.2 | Postgraduate | 406 | 26.9 |

| Other | 87 | 5.8 | Other | 26 | 1.7 |

| Marital status | Occupation | ||||

| Single | 817 | 54.2 | Homemaker | 58 | 5.8 |

| Married | 397 | 26.3 | Student | 256 | 25.6 |

| Widower | 17 | 1.1 | Employee | 254 | 25.4 |

| Divorced or separated | 111 | 7.4 | Unemployed | 48 | 4.8 |

| Cohabitation | 157 | 10.4 | Professional | 356 | 5.6 |

| Other | 9 | 0.6 | Retired | 27 | 2.7 |

| Paternity | Residence in Mexico (n = 1426) | ||||

| Yes | 583 | 38.7 | Mexico City | 688 | 42.8 |

| No | 925 | 61.3 | State of Mexico | 265 | 18.6 |

| Medical comorbidity (n = 417) | Other states | 473 | 33.2 | ||

| Hypertension | 85 | 20.4 | Disease | ||

| Diabetes | 43 | 10.3 | Yes | 400 | 26.5 |

| Cancer | 29 | 7.0 | No | 1108 | 73.5 |

| Depression | 75 | 18 | |||

| Anxiety | 116 | 27.8 | Health insurance | ||

| Other | 196 | 47.0 | Yes | 1035 | 68.6 |

| No | 473 | 31.4 | |||

| Prior mental health care | |||||

| Yes | 929 | 61.6 | |||

| No | 579 | 38.4 | |||

Different behavioral areas related to the contingency and its psychosocial consequences were explored. Most participants (92 %) referred that they would undergo the test for COVID-19 detection, whereas 90 % did not have any relative or friend with the virus infection at that moment.

Regarding self-care behaviors, adequate adherence to recommendations stood out, since 80 % complied with not attending meetings or crowded places, 88 % frequently washed or disinfected their hands, 66 % kept the recommended distance (1.5 to 2 m) and 72 % stayed home.

As for coping strategies, 41 % cared little about getting sick, approximately 15 % were frequently worried about getting the disease, while 31 % continually analyzed their bodily sensations, interpreting them as symptoms of the disease. Half the participants frequently used past stressing experience strategies to reduce fear and generated a list of activities to stay active; the same percentage claimed that they maintained an optimistic and objective attitude towards the situation, as well as to have support networks to talk and solve problems (Table 2).

Table 2 Coping and self-care behaviors in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic in surveyed individuals with regard to symptoms of depression and anxiety

| Never | Rarely | Frequently | Almost always | Always | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| How often do you worry about getting infected with COVID-19? | 7.4 | 6.9 | 629 | 41.7 | 523 | 34.7 | 164 | 10.9 | 81 | 5.4 |

| Are you continually analyzing and interpreting your bodily sensations as symptoms of disease? | 329 | 21.8 | 704 | 46.7 | 340 | 22.5 | 84 | 5.6 | 51 | 3.4 |

| Do you feel frustrated by the effects COVID-19 has had on your life? | 207 | 13.7 | 585 | 38.8 | 436 | 28.9 | 185 | 12.3 | 95 | 6.3 |

| When you are afraid, do you rely on experiences you have had in similar situations to reduce fear? | 140 | 9.3 | 361 | 23.9 | 437 | 29.0 | 365 | 24.2 | 205 | 13.6 |

| You generate a list of daily activities and try to keep busy | 138 | 9.2 | 302 | 20.0 | 390 | 25.9 | 390 | 25.9 | 288 | 19.1 |

| You maintain an optimistic and objective attitude towards the situation | 20 | 1.3 | 134 | 8.9 | 423 | 28.1 | 521 | 34.5 | 410 | 27.2 |

| You have someone you can lean on or with whom you can talk about your problems | 40 | 2.7 | 200 | 13.3 | 244 | 16.2 | 341 | 22.6 | 683 | 45.3 |

| Visual analogue scale score | ||||||||||

| 0-1 | 2-3 | 4-5 | 6-7 | 8-10 | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| How much have you followed the following recommendations? | ||||||||||

| − Not attending social gatherings or crowded places | 44 | 2.9 | 44 | 2.9 | 82 | 5.4 | 92 | 6.8 | 1236 | 82.0 |

| − Washing or disinfecting your hands frequently | 10 | 0.7 | 12 | 0.8 | 40 | 2.7 | 97 | 6.4 | 1349 | 89.4 |

| − Keeping at least 1.5 m away from other people | 64 | 4.3 | 46 | 3.3 | 167 | 11.1 | 225 | 26.3 | 1006 | 66.8 |

| − Staying home | 97 | 6.5 | 49 | 3.3 | 120 | 7.9 | 123 | 8.8 | 1109 | 73.0 |

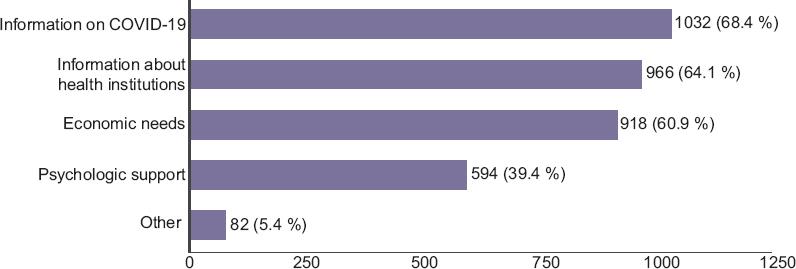

As regards specific needs to face the current health problem, 68 % answered that having information about the disease was essential, as well as knowing the health institutions they can attend and covering the economic needs for subsistence; 34 % considered it necessary for the psychological aspect to be taken care of (Figure 1).

The anxiety and depression symptom scores had means of 12.35 and 14.4, respectively. The fact that 20.8 % had symptoms of severe anxiety, and 27.5 %, of severe depression, stood out (Table 3). Participants without children, with medical conditions and a history of mental health care were observed to have higher levels of depression and anxiety (p <0.001). Specifically, the female gender reported higher levels of anxiety, and single individuals, higher levels of depression (p <0.001) (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 3 Level of COVID-19 pandemic-derived anxiety and depression

| Anxiety | Depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | n | % | Level | n | % |

| Minimal | 525 | 34.8 | Minimal | 598 | 39.7 |

| Mild | 253 | 16.8 | Mild | 337 | 22.3 |

| Moderate | 416 | 27.6 | Moderate | 158 | 10.5 |

| Severe | 314 | 20.8 | Severe | 415 | 27.5 |

| Total | 1508 | 100.0 | Total | 1508 | 100.0 |

Table 4 Sociodemographic variables comparison between participants with symptoms of anxiety (n = 1508)

| Variable | GAD-7 score | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | p | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Females | 352 | 67 | 199 | 78.7 | 316 | 76 | 256 | 81.5 | 1123 | 74.5 | < 0.001 |

| Males | 173 | 33 | 54 | 21.3 | 100 | 24 | 58 | 18.5 | 385 | 25.5 | |

| Paternity | |||||||||||

| Yes | 223 | 42.5 | 98 | 38.7 | 158 | 38 | 104 | 33.1 | 583 | 38.7 | 0.008 |

| No | 302 | 57.5 | 155 | 61.3 | 258 | 62 | 210 | 66.9 | 925 | 61.3 | |

| Marital status | |||||||||||

| Single | 268 | 51 | 142 | 56.1 | 215 | 51.7 | 192 | 61.1 | 817 | 54.2 | 0.151 |

| Married | 145 | 27.6 | 71 | 28.1 | 112 | 26.9 | 69 | 22.0 | 397 | 26.3 | |

| Widowed | 9 | 1.7 | 3 | 1.2 | 4 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 17 | 1.1 | |

| Divorced/separated | 40 | 7.6 | 19 | 7.5 | 28 | 6.7 | 24 | 7.6 | 111 | 7.4 | |

| Cohabitation | 60 | 11.4 | 17 | 6.7 | 54 | 13 | 26 | 8.3 | 157 | 10.4 | |

| Other | 3 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.6 | |

| Disease | |||||||||||

| Yes | 105 | 20 | 58 | 22.9 | 105 | 25.2 | 132 | 42 | 400 | 26.5 | < 0.001 |

| No | 420 | 80 | 195 | 77.1 | 311 | 74.8 | 182 | 58 | 1108 | 73.5 | |

| Place of residence | |||||||||||

| Mexico City | 237 | 48 | 122 | 50.6 | 178 | 45.3 | 151 | 50.7 | 688 | 48.2 | 0.645 |

| State of Mexico | 87 | 17.6 | 45 | 18.7 | 75 | 19.1 | 58 | 19.5 | 265 | 18.6 | |

| Another state | 170 | 34.4 | 74 | 30.7 | 140 | 35.6 | 89 | 29.9 | 473 | 33.2 | |

| Medical insurance | |||||||||||

| Yes | 348 | 66.3 | 180 | 71.1 | 278 | 66.8 | 229 | 72.9 | 1035 | 68.6 | 0.120 |

| No | 177 | 33.7 | 73 | 28.9 | 138 | 33.2 | 85 | 27.1 | 473 | 31.4 | |

| Previous mental health care | |||||||||||

| Yes | 265 | 50.5 | 155 | 61.3 | 274 | 65.9 | 235 | 74.8 | 929 | 61.6 | < 0.001 |

| No | 260 | 49.5 | 98 | 38.7 | 142 | 34.1 | 79 | 25.2 | 579 | 34.8 | |

GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7.

Table 5 Sociodemographic variables comparison between participants with symptoms of depression (n = 1508)

| Variable | PHQ-9 score | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | p | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Females | 429 | 71.7 | 247 | 73.3 | 127 | 80.4 | 320 | 77.1 | 1123 | 74.5 | 0.024 |

| Males | 169 | 28.3 | 90 | 26.7 | 31 | 19.6 | 95 | 22.9 | 385 | 25.5 | |

| Paternity | |||||||||||

| Yes | 285 | 47.7 | 124 | 36.8 | 51 | 32.3 | 123 | 29.6 | 583 | 38.7 | < 0.001 |

| No | 313 | 52.3 | 213 | 63.2 | 107 | 67.7 | 292 | 70.4 | 925 | 61.3 | |

| Marital status | |||||||||||

| Single | 274 | 45.8 | 175 | 51.9 | 95 | 60.1 | 273 | 65.8 | 817 | 54.2 | < 0.001 |

| Married | 196 | 32.8 | 94 | 27.9 | 39 | 24.7 | 68 | 16.4 | 397 | 26.3 | |

| Widowed | 10 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 1.4 | 17 | 1.1 | |

| Divorced/separated | 45 | 7.5 | 23 | 6.8 | 9 | 5.7 | 34 | 8.2 | 111 | 7.4 | |

| Cohabitation | 69 | 11.5 | 42 | 12.5 | 14 | 8.9 | 32 | 7.7 | 157 | 10.4 | |

| Other | 4 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.6 | |

| Disease | |||||||||||

| Yes | 117 | 19.6 | 80 | 23.7 | 46 | 29.1 | 157 | 37.8 | 400 | 26.5 | < 0.001 |

| No | 481 | 80.4 | 257 | 76.3 | 112 | 70.9 | 258 | 62.2 | 1108 | 73.5 | |

| Place of residence | |||||||||||

| Mexico City | 278 | 48.7 | 149 | 47.2 | 67 | 46.5 | 194 | 49.1 | 688 | 48.2 | 0.173 |

| State of Mexico | 95 | 16.6 | 54 | 17.1 | 39 | 27.1 | 77 | 19.5 | 265 | 18.6 | |

| Another state | 198 | 34.7 | 113 | 35.8 | 38 | 26.4 | 124 | 31.4 | 473 | 33.2 | |

| Health insurance | |||||||||||

| Yes | 421 | 70.4 | 232 | 68.8 | 113 | 71.5 | 269 | 64.8 | 1035 | 68.6 | 0.100 |

| No | 177 | 29.6 | 105 | 31.2 | 45 | 28.5 | 146 | 35.2 | 473 | 31.4 | |

| Prior mental health care | |||||||||||

| Yes | 296 | 49.5 | 224 | 66.5 | 106 | 67.1 | 303 | 73 | 929 | 61.6 | < 0.001 |

| No | 302 | 50.5 | 113 | 33.5 | 52 | 32.9 | 112 | 27 | 579 | 38.4 | |

PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

It should be noted that there may be variability in each countrys data, since the survey was conducted at different times according to the epidemiological phase of each nation. However, 88.4 % of participants considered that they will experience negative repercussions in their individual economy.

A positive, middle-magnitude and statistically significant correlation was identified (Pearsons r = 0.721, p < 0.001), between the levels of depression and anxiety symptoms.

Discussion

The main strategies to fight coronavirus COVID-19 transmission involve self-care behaviors, which should be approached from a psychological perspective, since they require modification or implementation of behaviors in people who apparently have no immediate reinforcing mechanisms, which complicates their execution.

Higher levels of anxiety and depression were identified than those reported in the SARS and influenza pandemics, which denotes a larger effect on general population mental health. Belonging to the female gender, not having children, a single marital status, medical comorbidity and a history of mental health care coincided with the variables indicated in the literature as being related to the presence of greater psychological symptoms; in addition, economic concerns, repercussions of the pandemic on daily life and academic backlog were identified.1 The presence of a medical condition was reported by 26.5 % of the sample, mainly of a cardiometabolic nature, which means that this group is at higher risk of becoming seriously ill with COVID-1914, and during the pandemic it might face difficulties for obtaining adequate treatment.9

One possible explanation for high levels of anxiety and depression is high exposure to information about COVID-19, which Avittey associates with constant exposure to overwhelming news headlines and misinformation.15

A need for general information about the health institutions people can resort to was identified, as well as concern about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy. Family income instability or decrease has been identified as a significant factor in anxiety during the crisis.16

Even though acceptable adherence to health recommendations was recorded in the present study, 5.8 % did not stay away from meetings, 7.4 % did not keep appropriate distance from people and 9.8 % continued to leave home, a situation that entails repercussions on public health, since dissemination and transmission of the virus increases inasmuch as confinement and social distancing strategies are not followed.

Finally, although adequate psychological strategies to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic were identified, half the participants did not have such tools or conditions to adapt to the situation; therefore, it is necessary to focus on the population particular needs and cover them to help improve coping strategies. Receiving mental health care was considered necessary by 24 % of participants; however, 72 % did not have any remote care service, either by phone or online.

It is relevant to consider recommendations such as those reported by Li,9 who claims that the population exposed to COVID-19 can be classified in four levels:

1. People who are more vulnerable to mental health problems, such as hospitalized patients with confirmed infection or serious physical condition, frontline health professionals, and administrative personnel.

2. Isolated patients and in clinics with atypical infection symptoms.

3. Individuals with level 1 and 2 contacts, i.e., family members, colleagues, friends, and rescue workers.

4. People affected by epidemic prevention and control measures, susceptible people and the general population.

Among the limitations, it should be noted that the sample was collected by convenience and that a cross-sectional research design was used; therefore, making a prospective follow-up is suggested, which will allow changes in symptoms and safety measures to be observed as the public health situation is modified.

Conclusions

Mental health problems in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic represent a challenge for the public health system; therefore valid and reliable psychosocial interventions are required to timely identify the onset and intensity of symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as to assess the effects of clinical and community psychosocial interventions.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)