Marriage is an appreciated worldwide institution. Since more than 90% of the world population marries at least once in their life (Javanmard & Garegozlo., 2013), it affects a large number of people. Statistics also suggest that nearly half of first marriages end in divorce (Brock & Lawrence, 2008). Thus, the relevance of understanding how people choose their partners and what features can predict a satisfactory relationship (Luo, 2009). Stability, family harmony and their association with factors, such as role distribution and fairness, have been studied in recent years (Stanfors & Goldscheider, 2017). Associations with fertility, offspring, and stability of the relationship or with the couples’ work outside and inside the home (Bernardi & Martinez-Pastor, 2011; Ruppanner, Bernhardt, & Branden, 2017) have also been studied. However, there is still much to investigate and efforts from multiple theoretical and methodological approaches are necessary to try to answer the question of why people decide to join, stay together and have offspring. Studies on marital satisfaction state that for partners to be compatible there must be a complex fit of two types of characteristics (Buss, 2004): complementarity and similarity. Complementarity relates to one partner having resources and skills that differ from their counterpart. The similarity hypothesis holds that people are seeking a partner like themselves, as similarity generates attraction (Díaz-Morales Estevez, Barreno, & Prieto, 2009).

When talking about choosing a partner similar to ourselves we refer to positive assortative mating, whereas if we choose a complementary person, we refer to negative assortative mating (Figueredo, Sefcek, & Jones, 2006; Russell & Wells, 1994). While some studies indicate that spouses are chosen on the basis of genetic similarity (Lucas et al., 2004; Russell & Wells, 1991, 1994), recent studies indicate that other factors, such as educational level (Domingue, et al., 2014), cognitive functioning and personality features (Botwin, Buss, & Shackelford, 1997; Díaz-Morales et al., 2009), are stronger predictors. This similarity maximizes the probability of success and reduces the risk of abandonment or dissolution of the relationship (Buss, 2004; Cabrera & Aya, 2014; Chi, Epstein Fang, Lam, & Li, 2013; Esteve & McCaa, 2007).

Additional evidence in support of this hypothesis is found in studies examining the similarity between the spouses under the paradigm of homogamy (Esteve & McCaa, 2007; Rammstedt & Schupp, 2008). Homogamy can be understood as the similarity of status in different life domains. For several decades, homogamy has been studied in terms of income or socioeconomic status (Kalmijn, 1991), education (Shafer, 2013b), ethnicity (Frias & Angel, 2013), religion (Heaton & Pratt, 1990; Kalmijn,, 1991; Schramm, Marshall, Harris, & Lee, 2012), age (Shafer, 2013a), personality (Bon et al, 2013), and intellectual ability (Lucas et al., 2004), among other variables. The concept of homogamy is also of interest in the reproduction of social class structure (Rodríguez, 2008; Mäenpää & Jalovaara, 2013). From this point of view, homogamy is considered an indicator of social openness: the lower the level of homogamy, the more open a society and the less relevant the barriers between different groups (Rodríguez, 2008) and the greater the acceptance of nontraditional unions, the greater the tolerance of partner differences (Schwartz & Graf, 2009). Conversely, homogamy functions as a mechanism of intergenerational reproduction of inequality (Velázquez, 2015).

When referring to situations opposite to homogamy, the term heterogamy is used (López-Ruiz et al., 2009; Rodríguez, 2008, 2012). Heterogamy reveals the interaction of people across social boundaries of groups and also shows that members of different groups accept each other (Esteve & Cortina, 2010; Rodríguez, 2012). The position of women within the couple is usually taken as the reference point to distinguish two types of situations: hypergamy and hypogamy (López-Ruiz et al., 2009). Hypergamy occurs when a woman partners with a man who is better positioned in the social hierarchy. Hypogamy occurs when the woman occupies the higher position in the hierarchy. These unions appear to be associated with socio-cultural characteristics as well. This class endogamy has been found in Latino cultures (Colantonio, Küffer, & Nazer, 2014).

One more concept closely related to the issue at hand is that of marital satisfaction, which can be understood as the individual’s attitude toward their partner and the relationship (Iboro & Akpan, 2011) or feelings about the relationship by one spouse through evaluative judgments (Fincham & Linfield, 1997). As some studies suggest, the more similar the partners, the more satisfying the relationship (Dillon, 2012; Gaunt, 2006) and to the contrary, when educational hypergamy occurs, marriage satisfaction is lower (Zhang, Ho, & Yip, 2012). Other authors show that compatibility, rather than similarity, is an important factor in maintaining marital satisfaction (Arrindell & Lutejin, 2000; Lucas et al., 2004; Luo, 2009; Russell & Wells, 1991). Here, it could be said that marital satisfaction is subjective, since it is related to one’s life, personality, and the expectations about marital relationships (Oprisan & Cristea, 2012). With the incorporation of women into the labor market, educational expansion and reduction of gender differences, caused the traditional marriage to face serious changes and challenges worldwide (Bedmar & Palma, 2011; Heaton & Mitchell, 2012). These changes have a potential to impact on the symmetry in relationships, the homogamy, and, accordingly, on marital satisfaction.

Despite the importance of this issue there are few studies that analyze the relationship between homogamy and marital satisfaction. Homogamy has been little studied in non-Western societies and a large number of studies on the subject have been made in the last century (Lewinsohn & Werner, 1997; Lucas et al, 2004). Studies in Spanish-speaking countries from different cultures, such as Spanish (European) and Latin contexts, are even more scarce and are focused on specific issues such as intimate partner violence (Flake & Forste, 2006; Frías & Angel, 2013) or li mited facets of homogamy, such as educational homogamy (Díaz-Morales et al, 2009; Esteve & McCaa, 2007; López-Ruiz et al, 2009). The current study on Dominican couples compared with Spanish couples, is therefore relevant because it offers both an overview of homogamy in Spain as well as an analysis of homogamy in a non-Western Latin country, and their cross-cultural comparison. And these, in relation to marital satisfaction.

Therefore, and in view of the previously discussed, in this study we aim to: (1) identify similarities and differences in marital satisfaction; (2) identify similarities and differences in status, and to (3) identify associations bet ween marital satisfaction and status. We expect to find differences among studied countries, as they have diffe rent sociocultural status, as well as differences based in the personal conditions that may impact on the symmetry in relationships. More specifically, we expect to find: (1) differences in marital satisfaction by country, gender, prior marriages, years of marriage, having or not children from previous marriages, and having or not children from the current marriage, (2) differences in status by country, years of marriage, prior marriages, having or not children from previous marriages, and having or not children from the current marriage. Also, we predict that (3) Homogamy will be associated to higher marital satisfaction in both countries.

Method

Participants

A stratified quota sampling was employed. The sample is composed of 600 participants that correspond to 300 pairs, of which 150 are Spanish couples and 150 are Dominican couples. In addition, the sample is divided into 100 couples who have been married up to six years, another 100 married between seven and twenty-four years and finally, 100 couples who have been married for twenty-five or more years, with 50% Spanish couples and 50% Dominican couples in all cases. Run test verified the randomness in data (Bartels, 1982) for marital satisfaction (z=-1.024, p=.31) and for status (z=.824; p=.410). Randomness was also found by gender (z=-.082; p=.935).

For 85.16% of couples, the current marriage is their first marriage, while for 11.66% it is their second, for 2.83% it is their third and for 0.33% it is the fourth marriage. As for the number of children with the current spouse, 22.20% of couples have no children, 20.80% have one, 31.80% have two children, 16.70% have three children, 5% have four children, and the remaining 3.5% have five or more children. As for the number of children living with the respondents, 29.8% have no children living with the couple, 27.3% have a child living with them, 30.2% have two, 10 % have three, and the other 2.7% have four or more children living with the couple. In general, these couples have been married an average of 17.08 years (SD = 13.74), with 68-years as maximum. The average age of the respondents is 45.45 years (SD = 13.75; range: 17 to 88). The average of years living together before marriage is 1.06 years (SD = 2.66).

Design and analyses

This is a descriptive and correlational cross-sectional study with ex post facto measures. It is also a comparative, cross-cultural study, understanding that the study of differences between cultures to estimate the generality of psychological laws on an event of interest is, in our case, marital satisfaction. Cultures can be considered as natural quasi-experimental treatments (Hernández, Fernández, & Baptista, 2006) that allow, using cultural modulation of human diversity, the study of the interaction between human behavior and variable social, economic, political, ecological and biological predictors. Descriptive analysis, together with Chisquared tests for categorical data, tests statistics (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha for reliability, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses) were utilized to assess the psychometric properties of the measures, when appropriate (Brown, 2015, Yu & Shek, 2014). Also, Pearson’s correlation for continuous variables were performed. Multivariate tests (Manova) were used to determine potential differences in the dependent variables taken together. If the multivariate analysis was significant, univariate analysis of variance was performed (Garson, 2015). An alpha =.05 was set for the analyses. Effect sizes (r, h2, n) have been estimated to determine the strength of the associations (Ferguson, 2009). The values of r=.2, and h2=.were established as cut-off for practical significance (Ferguson, 2009).

Procedure

Data were collected from Spanish and Dominican couples. In all cases, confidentiality and anonymity was guaranteed. Participants completed the questionnaire individually. The data collection was conducted between September 2013 and August 2014.

Measure

We used two parallel forms, one for the wives and the other for the husbands, of the general-purpose inventory Marriage Questionnaire (Russell & Wells, 1993; Weisfeld, Russell, Weisfeld, & Wells, 1992) that was provided by the authors. As is usual with this measure (Russell & Wells, 1994a, 1994b), only a small number of items were selected for this study. Specifically, we selected the 10 items that assess marital satisfaction (α=.87 for Spanish participants, and α =.73 for Dominican participants). Exploratory factor analysis allowed us to identify two factors: (1) Factor 1, composed by 5 items that assess positive feelings toward the relationship (α =.91 for Spanish participants, and α =.73 for Dominican participants); (2) Factor 2, composed by 5 items that assess negative feelings toward the relationship (α =.76 for Spanish participants, and α =.64 for Dominican participants). For the analyses, the scores from factor 2 were inverted, so for total scale, the higher the score, the higher the marital satisfaction.

Next, we performed a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis to check if the proposed two-model factor fitted both subsamples. Table 1 shows the parameter estimates (unstandardized and standardized) and r2 values for the model when using ML estimator. Note that all the items have medium-high r2 values, as well as high loadings in their respective factors. The hypothesized model appears to be a good fit to the data: X2 (68) = 159.003; p<.001; X2/ df=2.33. The GFI is .95, CFI is.95; RMSEA is.047 (90%CI: .038 to .057). In addition, the standardized regression weights of all variables were higher than .44 in both countries; the critical ratios (C.R.) of the regression weights were all significant and much higher than 1.96; all the variances were also significant (p<.001). The correlation between the two latent variables was .556 for Spanish participants (covariance=.311, SE=.055), and .489 for Dominican participants (covariance=.162, SE=.038). Altogether, the results offer support to the proposed two-factor model for both countries.

Table 1 Unstandardized loadings (Standard Errors), Standardized loadings, and r2 value for 3-factor confirmatory model

| Spain | Dominican Republic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized (S.E.) | Standardized | r2 | Unstandardized (S.E.) | Standardized | r2 | |||||

| IT054 | <--- | F1 | 1.114 | (.061) | .748 | .638 | 1.707 | (.279) | .515 | .239 |

| IT063 | <--- | F1 | 1.313 | (.059) | .856 | .767 | 1.886 | (.277) | .632 | .331 |

| IT067 | <--- | F1 | 1.213 | (.060) | .789 | .666 | 2.460 | (.338) | .780 | .329 |

| it006inv | <--- | F2 | 1.000 | (---) | .507 | .417 | 1.000 | (---) | .531 | .216 |

| it016inv | <--- | F2 | 1.320 | (.139) | .504 | .468 | 1.033 | (.199) | .443 | .319 |

| it018inv | <--- | F2 | 1.399 | (.128) | .684 | .254 | 1.144 | (.192) | .564 | .197 |

| it033inv | <--- | F2 | 1.899 | (.163) | .646 | .257 | 1.162 | (.217) | .465 | .281 |

| it035inv | <--- | F2 | 2.169 | (.172) | .816 | .623 | 1.388 | (.232) | .574 | .608 |

| IT070 | <--- | F1 | 1.290 | (.057) | .876 | .733 | 1.653 | (.254) | .575 | .399 |

| IT009 | <--- | F1 | 1.000 | (.---) | .799 | .559 | 1.000 | (.---) | .489 | .265 |

Note: Dashes (---) indicate the standard error was not estimated. r2= Squared Multiple Correlations

In addition, and according to the study by Weisfeld et al. (1992), we used seven items of the multipurpose marriage questionnaire in parallel forms to assess status, in various aspects, such as in health (How is your health?, item 1), education (How much education have you received?, item 2), income (How much do you contribute to all household income, item 3), domestic roles (How much housekeeping do you do?, item 4), intellectual capacity (is your spouse more intelligent than you?, item 5), financial status (item 6: Will you be in a difficult position if divorced?, and decision making (Item 7: Who makes important decisions?). As in previous questionnaire, negative-worded items were recoded so, the higher the scores the higher the status. In addition, as Weisfeld et al. (1992) suggest, after passing the parallel forms, couples’ homo gamy was calculated by subtracting the scores obtained by the wife from the scores obtained by the husband (i.e., husband score - wife scores). Thus, positive scores indicate that the husband has higher status (i.e., hypergamy), while negative scores indicate that the wife has higher status (i.e., hypogamy or husbands having lower status).

Results

Marital satisfaction and associated variables

Concerning our first hypothesis, regarding marital satisfaction, the multiple analysis of variance revealed significant differences in marital satisfaction by countries [Wilks’ Lambda=.0.920, F(3, 596)=17.3; p<.001]. The univariate tests revealed that there were significant differences in factor 1 (F=35.10; df=1; p<.001; h2=.06), and in the total scale (F=8.84, df=1; p<.05; h2=.02), but not differences in factor 2 (F=1.31, df=1; p>.05). Dominican couples were significantly more satisfied in factor 1 and total (M=4.77, SE=.07, and M=4.57, SE=.05, respectively), than Spanish couples (M=4.23, SE=.07, and M=4.34, SE=.05, respectively).

On the impact of gender, the multiple analysis of variance revealed lack of significant differences [Wilks’ Lambda=.999, F(3, 596)= 0.181; p=.91]. Concerning years of marriage and its potential effect, significant differences were found in the multivariate test [Wilks’ Lambda=.0.944, F(6, 1190)=5.85; p<.001]. Univariate tests revealed significant differences in factor 1 (F=11.2; df=2; p<.001; h2=.04), factor 2 (F=11.7; df=2; p<.001; h2=.04), and total (F=16.4; df=2; p<.001; h2=.05). Post hoc comparisons revealed that the most recent couples (i.e. up to six years) were significantly more satisfied (M=4.75; SE=.06) than the other two groups (i.e. couples married between 7- 24 years, and couples married for 24 years or more) (M=4.28; SE=.07, and M=4.34; SE=.06, respectively). On the impact of previous marriages or not, the multiple analysis of variance revealed a lack of significant differences [Wilks’ Lambda=.0.997, F(3, 596)=.574; p=.63].

Continuing with our first hypothesis, having children from previous marriages significantly impact on marital satisfaction [Wilks’ Lambda=.986, F(3, 596)= 2.88; p<.05]; univariate tests revealed only marginal differences in factor 2 (F=3.56; df=1; p=.06; h2=.01), and those who have children from previous marriages scored lower on factor 2 (M=4.20; SE=.12), than those who do not have them (M=4.44; SE=.05). In the same vein, having children from current marriage significantly impact on marital satisfaction [Wilks’ Lambda=.973, F(3, 596)= 5.55; p<.001]. Univariate tests revealed significant differences in factor 1 (F=4.04; df=1; p<.05; h2=.01), factor 2 (F=15.72; df=1; p<.001; h2=.03), and total (F=12.31; df=1; p<.001; h2=.02). Those who have children from the current marriage scored lower, than those who do not have them, in factor 1 (M=4.45, SE=0,05, vs. M=4.67, SE=0,09), factor 2 (M=4.33, SE=0,05, vs. M=4.73, SE=0,09), and total scale (M=4.39, SE=0.04, vs. M=4.70, SE=0.08).

In sum, as expected, we have found differences in marital satisfaction by country, years of marriage, and having or not children from either current or previous marriages. Yet, in contrast to our predictions, no differences were found by gender or by having or not previous marriages. So, our first hypothesis has received some support.

Status and associated variables

In order to identify similarities and differences in status, we first performed analyses of the correlations between husbands and wives scores (7-item test), with data disaggregated by country (see Table 2). These results suggest that spouses are matched by similarity in their health and education or by the perception of similarity in intelligence or advantages of staying together, at least from the economic point of view. Some differences are seen in the results by country. In particular, economic heterogamy is more marked in Spain, while for Dominicans there is no significant association with this variable.

Table 2 Correlations between husbands and wives scores (7-item test), disaggregated by country

| Items | Spain | Dominican Republic |

|---|---|---|

| IT01 (health) | .369** | .263** |

| IT02 (education) | .232** | .511** |

| IT03 (income) | -.304** | -.112 |

| IT04 (house-keeping) | -.091 | .146 |

| IT05 (intelligence) | .282** | .258** |

| IT06 (divorce) | .242** | .234** |

| IT07 (decisions) | .086 | .023 |

| Total | -.218** | .189* |

Note: ** significant with p<..01 (two-tails).* significant with p<.05 (two-tails).

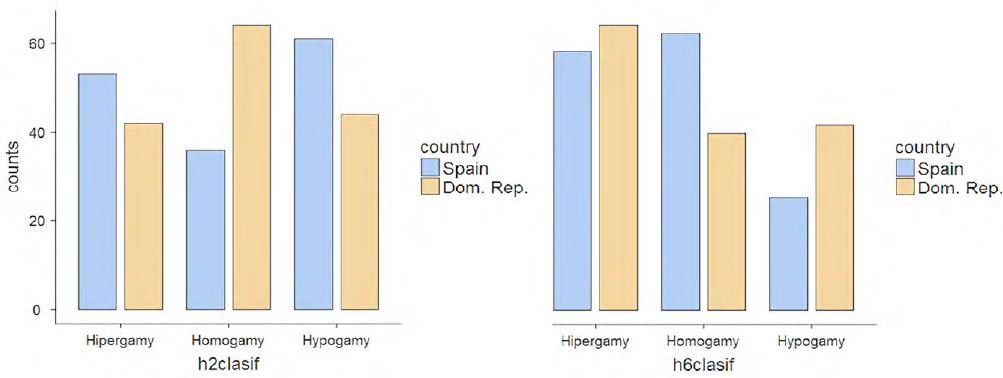

To contrast our second hypothesis, we first recoded, for each of the items on the status scale, the percentage of answers that reveal if husbands have less, equal or higher scores, namely, status, with hypogamy, meaning that husbands have lower status than wives, homogamy, meaning equal status, and hypergamy, meaning husbands having higher status than wives. Then, we calculated the potential association between these variables and sociocultural factors, by performing Chisquared tests. On the potential association of country, analyses were significant in education (X2=11.9; df=2; p=.003; n=.20), and economic impact of a potential divorce (X2=9.51; df=2; p=.009; n=.18). Data revealed that, for Spanish participants, there is more education hypogamy, whereas for Dominican participants there is more education homogamy. Concerning financial issues in case of divorce, while there is more homogamy for Spanish participants, there is more hypergamy for Dominicans (see Figure 1).

Having previous marriages or not was not associated to differences in status. Concerning potential association between status and years married, significant associations were found in health (X2=14.7; df=4; p=.005; n=.16), and while for couples married up to six years, homogamy or hypogamy prevails (40.4%, each), for couples married 24 years or longer, hypergamy prevails (43.4%). In other words, for the group with more years married, husbands have lower health status. Having children from previous marriages and having children from current marriage did not significantly affect status.

In sum, the analyses concerning the second hypothesis revealed that contrary to our expectations, the most significant feature associated to status is the country.

Association between status and marital satisfaction

To contrast our third hypothesis, that predict that homogamy will be associated to higher marital satisfaction for both countries, we have estimated the scores in marital satisfaction among the three types of status (hypogamy, homogamy, and hypergamy) for the seven items of the scale. The analyses revealed significant differences in marital satisfaction based on health status [Wilks’ Lambda=.951, F(6, 584)= 2.47; p<.05]. Univariate tests revealed significant differences in factor 2 of marital satisfaction (F=4.54; df=2; p<.05; h2=.01), with no significant differences by country. Post hoc comparisons revealed that hypergamy in health status have significantly smaller marital satisfaction than hypogamy situations (M=4.14, SE=0.11; and M=4.57, SE=0.10, respectively).

Also, significant differences in marital satisfaction based on education status were found [Wilks’ Lambda=.938, F(6, 584)= 3.17; p<.01]. Univariate tests revealed significant differences in factor 1 (F=5.46; df=2; p<.01; h2=.03), and total scale (F=3.61; df=2; p<.05; h2=.XX). There were also significant differences in factor 1 by country (F=12.32; df=1; p<.001; h2=.04), as well as by the interaction of status by country (F=4.90; df=2; p<.05; h2=.03). Post hoc comparisons revealed that hypogamic education status situations have significantly smaller marital satisfaction than hypergamic situations (M=4.18, SE=0.11; and M=4.58, SE=0.11, respectively). In addition, hypergamy situations in Spain and Dominican Republic scored significantly higher than hypogamy situations in Spain. Homogamy situations in Dominican Republic scored significantly higher than hypogamy situations in Spain. Finally, hypogamy situations in Spain scored significantly lower than hypogamy situations in Dominican Republic.

Likewise, significant differences in marital satisfaction based on economic status were found [Wilks’ Lambda=.937, F(6, 584)= 3.21; p<.01]. Univariate tests revealed significant differences in factor 1 (F=6.64; df=2; p<.01; h2=.04). There were also significant differences in factor 1 by country (F=11.09; df=1; p<.001; h2=.03), with Dominicans scoring significantly higher than Spaniards (M=4.8, SE=.015, and M=4.34, SE=.10, respectively). Economic hypergamy was associated to significantly higher marital satisfaction (factor 1) than homogamic and hypogamic status. Spaniards with hypergamy status scored significantly higher than the other two groups from Spain. Dominicans with hypogamic status scored significantly lower than the other two groups from the same country.

Additionally, significant differences in marital satisfaction based on housekeeping status were found [Wilks’ Lambda=.920, F(6, 584)= 4.12; p<.001]. Univariate tests revealed significant differences in factor 1 (F=10.230; df=2; p<.001; h2=.06), and total scale (F=6.84; df=2; p=.001; h2=.04), without significant differences by country. Hypogamy status was associated to significantly higher marital satisfaction (factor 1) than hypergamy status (M=4.88, SE=.14, M=4.34, SE=.07, respectively).

Status on intelligence was not associated to significant differences in marital satisfaction. Economic status in case of divorce was not associated to significant differences in marital satisfaction either. Yet, significant differences in marital satisfaction based on decision making status were found [Wilks’ Lambda=.950, F(6, 584)= 2.55; p<.05]. Univariate tests revealed significant differences in factor 1 (F=5.01; df=2; p<.01; h2=.03), where significant differences by country were also identified (F=17.22; df=1; p<.001; h2=.05), with Dominicans scoring significantly higher. Hypogamic status in decision making was associated to significantly lower marital satisfaction in factor 1 than homogamic and hypergamic status.

To summarize those findings, neither the status on intelligence nor the economic impact in case of divorce are related to marital satisfaction. Some situations are associated to higher marital satisfaction: economic hypergamy, and housekeeping hypogamy. Other situations are associated to lower marital satisfaction: health hypergamy, education hypogamy, and decision making hypogamy. So, in general, complementary situations rather than similar situations impact most significantly in the outcomes in terms of marital satisfaction. Thus, our hypothesis has not received support.

Discussion

The analysis of marital satisfaction indicates that some features of marital satisfaction are associated with sociocultural factors. For example, having children is associated to lower marital satisfaction. Role conflict, arising from having to combine work and family, could be at the root of these findings, which are aligned to those studies concluding that not only biological but also cultural factors are strong predictors of wanting another child (Yang, 2017). Likewise, couples with traditional housework allocations are more likely to have a child (Ruppanner, Bernhardt, & Branden, 2017). These findings also support the relevance of cooperating for raising one’s offspring, as found in previous studies (Dillon, Nowak, Weisfeld, Weisfeld, Shattuck, & Imamoğlu, 2015). Years married also appear to reduce marital satisfaction. These results are in line with previous studies in other countries (Twenge, Campbell, & Foster, 2003; Wight, Raley, & Bianchi, 2008).

As regards status, for Spanish couples, economic heterogamy is more marked, hypogamy predominates in education and homogamy is more prevalent in economic impact of a divorce. The finding that, in Spain, education hypergamy is obsolete to the point of reversal, agrees with previous studies (Bernardi & Martinez-Pastor, 2011; Esteve & Cortina, 2005) and suggest the existence of a more dynamic society. For Dominican couples, education homogamy is more prevalent, which contrast to the growing educational similarity that has been found in couples in other countries such as the USA (Schwartz & Graf, 2009). Also, for Dominican couples, hypergamy in economic impact of a divorce is also more prevalent. Taking these findings together may reflect, on the one hand, differences in social class structure, as the lower the level of homogamy, the more open a society and the less relevant the barriers between different groups (Rodríguez, 2008). On the other hand, the fact that men have significantly higher scores on the economic features and significantly lower scores in housekeeping involvement, confirms the persistence of gender roles in Spanish speaking countries and power structures associated with male gender, in contrast to other studies carried out in strong egalitarian societies such as Sweden (Ruppanner et al., 2017). These findings suggest that attaining equal opportunities in a society with clear role differentiation remains difficult. Women, regardless their competencies, education, etc., are relegated to home chores and less money and power in decision making. In sum, this study allows us to glimpse the rigidity and permeability of social stratification barriers and the traits that structure social inequality in our societies (Rodríguez, 2012).

The next studied issue was the association between status and marital satisfaction; that is, are similar couples happier than dissimilar ones? According to the evolutionary approach to homogamy, both concepts should be positively related. In this regard, the first finding is that, contrary to our expectations, homogamy status in all of the studied variables (health, education, finances, house-keeping, intelligence, economic impact of a divorce, decision making) is not associated to higher marital satisfaction. The second noteworthy finding is that, even though Dominican and Spanish couples score significantly different in several variables, there is no significant interaction between status scores and countries, meaning that both countries follow similar patterns. The only exception are the findings in education status where, while in Spain hypergamy is associated to higher marital satisfaction, homogamy is associated to higher marital satisfaction in Dominican Republic. These findings could suggest that power relations do not affect marital satisfaction, at least in the studied couples. A tentative explanation could be related to the fact that, in relatively traditional contexts, as those studied, unequal relationships are accepted and not disputed. In fact, we have found that, while some hypergamy situations, such as economic, are associated to higher marital satisfaction, other hypergamy situations, such as health, are associated to lower marital satisfaction. In the same vein, while some hypogamy situations, such as housekeeping, are associated to higher marital satisfaction, other hypogamy situations, such as education and decision making, are associated to lower marital satisfaction. These trends depict rather traditional roles, where men are the providers and women are the caregivers. The fact that these roles significantly impact marital satisfaction seem to reflect that the studied countries have social structures with assumed or accepted role distribution. Further studies that include other variables, such as personality characteristics (Arrindell & Lutejin, 2000), as well as features from the extended family, or work contexts (Cabrera & Aya, 2014), could help better explain marital satisfaction.

We do not wish to conclude without first mentioning a series of shortcomings of the present study. First, because this is a study with a cross-sectional design with ex post facto measures, it is not possible to establish cause-effect relationships between the studied variables. Second, we have only included successful couples in the study, so findings cannot be extrapolated to those couples who did not last or to couples in consensual unions. This fact could also explain the small effects size of the identified differences. Further studies with unsuccessful (i.e. divorced) couples will probably obtain much higher effect sizes. Third, only questionnaires have been included in the study, so for future research efforts, additional measures, such as semi-structured interviews, are advisable. Even with these shortcomings, the current findings allow us to state that relationship between homogamy and marital satisfaction is a cross-cultural phenomenon moderated by sociocultural variables; by traits valued in a society, by greater or lower permeability between classes and by the degree of accepted asymmetry in different roles and personal characteristics. Further studies with complementary qualitative methodologies, and additional variables, can contribute to shed light on these complex associations.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)