The genus Iresine P.Browne comprises mostly dioecious herbs, shrubs and trees and is the most speciose lineage of the Amaranthaceae in Mesoamerica and México (Borsch 2001, Zumaya et al. 2013, Borsch et al. 2018). It is one of the medium-sized genera of the Amaranthaceae s.str. (Hernández-Ledesma et al. 2015) where it belongs to the monophyletic subfamily Gomphrenoideae (Sánchez del-Pino et al. 2009). Like all members of Gomphrenoideae, the species of Iresine are characterized by unilocular anthers but pollen differs in the Iresine clade by mesoporia with evenly spread microspines and punctae and a specific aperture type, whereas the core Gomphrenoideae, that includes all other genera of the subfamily, possess metareticulate pollen (Borsch et al. 2018). A comprehensive molecular phylogenetic analysis revealed two major clades within the monophyletic genus Iresine (Borsch et al. 2018), one of which contains the Iresine diffusa Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. species complex that extends throughout the Neotropics and a number of more widespread Mesoamerican species extending well into the Mexican highlands (e.g., I. interrupta Benth.) and in evergreen tropical forests north of Puebla (I. arbuscula Uline & W.L.Bray). The other clade (clade “A” in Borsch et al. 2018) contains just one Mesoamerican-Mexican species (I. latifolia (M.Martens & Galeotti) Hook.f.), whereas all other species are range-restricted in parts of the Mexican highlands or the northern deserts (e.g., I. ajuscana Suess. & Beyerle, I. cassiniiformis S.Schauer, I. discolor Greenm., I. hartmanii Uline, I. rzedowskii Zumaya, Flores Olv. & Borsch or I. valdesii Zumaya, Flores Olv. & Borsch). Divergence time estimates indicate a Miocene diversification of this Mesoamerican-Mexican clade “A”, whereas the crown group of the genus Iresine is much older (26.1 Ma [16.0-36.4 95 % HPD], Ortuño Limarino & Borsch 2020). Mexican Iresine speciation is likely fostered by geographic isolation and adaptation to different rainfall regimes with increasing humidity from North to South with conditions sustaining evergreen forests and the complex geological and paleoclimatological processes affecting plant diversity in northern Mesoamerica and the Mexican highlands (Ornelas et al. 2013, Mastretta-Yanes et al. 2015, Sosa et al. 2018). In order to better understand species limits in Iresine the examination of specimens belonging to putative entities indicated by morphology throughout their range was warranted.

During the past decade we have studied the genus using morphology, pollen micromorphology, and molecular phylogenetics what has resulted in the recognition and description of four new species to science (Zumaya et al. 2013, Flores-Olvera et al. 2016), and a comprehensive taxonomic backbone with 35 species currently accepted (Borsch et al. 2018). The state of knowledge for each of these accepted taxa was commented to be (A) a natural entity (monophyletic) as currently defined, (B) species limits not yet studied in detail, and (C) probably not a monophylum as currently defined, but requiring further study. Such varying degrees in understanding species limits reflect a typical situation in most genera of flowering plants, in which some species can be clearly delimited whereas this is not possible for others. In the case of Iresine we reported in addition to the 35 currently accepted species a morphotype which was similar to I. cassiniiformis and I. hartmanii in some characters but also differed in others and appeared in two different positions of subclade “A1” of the Mexican-Mesoamerican clade in our plastid and nuclear trees (Borsch et al. 2018).

These specimens provisionally annotated as “morphotype XXXIV” show medium-sized and loosely branched inflorescences with shortly cylindrical flower heads composed of long and thin flowers, positioned in a rectangular angle to the inflorescence axis. Based on these features the specimens resemble I. hartmanii and accordingly, were earlier often identified as this taxon in various herbaria (Zumaya 2008). Unlike that species, “morphotype XXXIV” differs by glabrous, green sepals and almost glabrous cauline leaves with a prominent midrib and lateral veins beneath. Iresine hartmanii was originally described from the Sonoran Desert and is characterized by a dense indumentum on all floral and vegetative parts. Its distribution extends into the Chihuahuan desert and to Durango, Jalisco, Michoacán to Querétaro and Zacatecas. However, specimens resembling “morphotype XXXIV” were collected exclusively in Oaxaca and Chiapas. This left the question if I. hartmanii is a distinct species restricted in the northern Mexican desert areas and adjacent drier parts of the central highlands, which can be circumscribed using molecular evidence and morphology, or if I. hartmanii represents a widespread taxon exhibiting clinal variation due to adaptation along a climatic gradient spanning deserts to evergreen tropical forest. A similar question arose with respect to I. cassiniiformis that was also resolved in subclade “A1” and apart from I. hartmanii shows the highest morphological similarity to “morphotype XXXIV” in this subclade although inflorescences of I. cassiniiformis (= I. grandis) are denser with much more numerous flower heads that also show a less pronounced cylindrical outline. One individual of “morphotype XXXIV” from Querétaro was even resolved as sister to the two I. cassiniiformis plants from Michoacán and Puebla that were included into phylogenetic analyses (Borsch et al. 2018), underscoring the need to evaluate the distinctness of both entities. Specifically, the question arose if I. cassiniiformis is a species restricted to deciduous tropical forest and shrublands in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt region or has a wider distribution, considering that morphologically similar plants were also found in Guatemala. It should be further noted that all other species currently recognized in the very well supported subclade A1 of the Mesoamerican-Mexican clade (I. ajuscana, I. alternatifolia, I. discolor, I. orientalis G.L.Nesom, I. rzedowskii) are each strongly differentiated morphologically and palynologically and in part are shown as being monophyletic (Zumaya et al. 2013, Borsch et al. 2018).

So far only very few samples from I. cassiniiformis, I. hartmanii and from plants provisionally annotated as “morphotype XXXIV” had been included into molecular phylogenetic trees (Borsch et al. 2018). One objective of this investigation was therefore to extend the sampling of each of the three entities to represent individuals from throughout their putative distribution areas and to reconstruct their phylogenetic relationships within the Mesoamerican-Mexican clade of Iresine. Using the same specimens, another objective was to assess a spectrum of morphological and palynological characters and states and to determine in how far “morphotype XXXIV” differs from either I. hartmanii or I. cassiniiformis and to evaluate if it there are discontinuous entities of morphological variation corresponding to lineages revealed by molecular phylogenetic analysis. Considering that individuals of “morphotype XXXIV” occur in the Flora Mesoamericana area, and that the question had to be answered whether I. hartmanii and I. cassiniiformis occur in the area covered by the Flora or not, this study also had the aim to elaborate an integrative taxonomic treatment for the respective plants to support a robust contribution for the genus Iresine in our upcoming treatment of the Amaranthaceae for Flora Mesoamericana.

Material and methods

Taxon sampling. About a dozen herbarium specimens identified with I. cassiniiformis and I. hartmanni were selected mostly from MEXU but also from B to represent plants from the different parts of Mexico. From “morphotype XXXIV” all available individuals were included. Subclade A of Iresine (Borsch et al. 2018) was the study group for the phylogenetic analysis with sequence data taken from that study, and I. arbuscula representing subclade B to root the trees. Detailed voucher information can be found in Supp. mat. 1. All specimens examined for morphology and shown on the distribution map are also included in the molecular data set and thus documented here.

Assessment of morphological data. Morphological characters and their states were assessed for individual specimens. The characters can be found in the description of I. viridipallida (see below) which is complete for both pistillate and staminate plants. Floral characters required the use of a stereo microscope. The leaf indumentum was imaged from representative specimens selected on the base of the molecular trees using a standard magnification for upper and lower surface. Pollen grains were taken from herbarium specimens (see Supp. Mat. 1), treated with dimethoxypropane and then critical point dried following Halbritter (1998). Dry grains were then put on silicium platelets mounted on aluminum stubs and examined in a Hitachi SU8070 cold field emission electron microscope at 1 kV without sputtering.

Analysis of specimen metadata and distribution mapping. The distribution map was produced using QGIS Brighton (2.6.1) employing layers from INEGI (2017) and CONABIO (1998). Geographic coordinates were obtained from specimen labels or georeferenced from the locality information on the label using Google Earth 7.1.8.3036 (32 bit).

DNA isolation, amplification and sequencing. Genomic DNA was isolated from herbarium specimens using a CTAB triple extraction method (Borsch et al. 2003). For plastid matK-trnK-psbA and nuclear ITS the same protocols were used as described in Borsch et al. (2018). For matK-trnK-psbA the psbA5-R primer (Shaw et al. 2005) was consistently employed as reverse amplification primer of the downstream half of this region, so that the psbA-trnK spacer could also be covered. Since the amplification of the plastid region trnL-F did not work well with DNAs isolated from herbarium specimens, we employed shorter fragments using the primers trnTc (Taberlet et al. 1991) and the in this study newly designed IREtrnL558R (5’-TCTATCTTTATTCTCGTCCG-3’) or alternatively IREtrnL3ex38R (5‘-AAGCTTTTGGGGATAGAGG-3’). An overlapping upstream half of the trnLF region was amplified with primers trnL460F (Worberg et al. 2007) and trnTf (Taberlet et al. 1991). The rpl16 intron including the upstream rps3-rpl16 spacer was amplified in two halves following the approach described in Borsch et al. (2018). Both strands were sequenced in trnLF and rpl16 using forward and reverse primers due to microsatellites. Pherograms were assembled in PhyDE v. 0.9971 (Müller et al. 2012) and inspected for erroneous base calls (mostly due to a slippeage effect following long poly A/T microsatellites). GenBank accession numbers of all sequences newly generated for this investigation and those used from earlier publications are available from Supplemental material.

Multiple sequence alignment and indel coding. New sequences were added to the multiple sequence alignments provided by Borsch et al. (2018) reduced to the taxa covered by this investigation in PhyDE v. 0.9971 by applying a motif-based alignment approach (Morrison 2009, Ochoterena 2009) using the criteria described in Löhne & Borsch (2005). This was straightforward as microstructural mutational events were already represented by sequences in the existing alignment. Hotspots of uncertain sequence homology (Ochoterena 2009) were adjusted and were smaller in extension due to the lack of more distant sequences of the core Gomphrenoideae and Amaranthoideae in this dataset as compared to Borsch et al. (2018). Indels were coded using the simple indel coding method (Simmons & Ochoterena 2000) implemented in SeqState (Müller 2005).

Phylogenetic analyses. All three inference methods, Bayesian Inference (BI), Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Maximum Parsimony (MP) were used. Model testing was implemented with ModelTest-NS (Darriba et al. 2020) and subsequent model selection using AIC. Models obtained for the plastid partitions were TVM+G for the trnK intron and trnK-psbA spacer, TVM+I for the matK CDS, TPM3uf+I for rpl16 and TVM+G for trnLF and SYM+G for nrITS. For the indel partition a binary model was applied. We implemented BI using MrBayes v. 3.2.5 (Ronquist et al. 2012) with four independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) runs each with four chains and 10 million generations, a burn in set at 25 %, then sampling trees every 1,000th generation. Convergence of chains and effective sampling size (ESS) were checked with Tracer v. 1.5.0 (Rambaut et al. 2014). For ML we used RAxML GUI 1.3 v. 7.2.8 (Stamatakis 2014) with 1,000 bootstrap replicates and for MP the version PAUP* v. 4.0a169 (Swofford & Bell 2021). The JK evaluation of node support was done with 10000 replicates, deleting 36.788 % of characters and maxtrees = 1. Phylogenetic results were then visualized based on the Bayesian majority rule consensus tree with posterior probabilities to indicate node support and parsimony Jackknife as well as ML bootstrap percentages plotted using TreeGraph 2 (Stöver & Müller 2010).

Results

Sequence data sets. The multiple sequence alignment of matK-trnK-psbA had 2,819 positions, from which two mutational hotspots from positions 535-588 and 730-742, corresponding to hotspots HS3 and HS4 in the dataset of Borsch et al. (2018) had to be excluded for analysis because of uncertain homology. A three nt inversion was present from positions 612-615 of the matK CDS which occurs throughout Amaranthaceae and frequently oscillates. The trnK-psbA spacer was not yet included in Borsch et al. (2018) but yielded another 263 sequence positions with additional variable and informative characters for our study group. The rpl16 intron showed the same polyA/T microsatellite hotspots (counted from the 5’ exon in MSA positions 35-47 (HS1), 183-196 (HS2), 232-239 (HS3), 293-307 (HS4), 661-666 (HS5), 733-746 (HS6), 818-824 (HS7), also excluded from analyses. Including the rps3-rpl16 spacer, the rpl16 5’ exon and the flanking part of the 3’ exon it had 1,509 positions. The trnL-F region had 1,102 positions, from which poly A/T microsatellites were excluded in positions 100-110 (HS2), 133-147 (HS3), 241-244 (HS4), 321-332 (HS5), 425-449 (HS6), 728-738 (HS7), and 985-997 (HS8). These correspond to earlier recognized hotspots (Borsch et al. 2018), from which only HS1 was not variable in this data set, and HS6 was considerably smaller due to the lower sequence divergence in this subset of Iresine as compared to the whole of Gomphrenoideae.

The final plastid sequence matrix comprised 5,256 characters, of which 43 were indels. A total of 364 characters was variable, of which 158 were informative (26 from the indel partition). The final ITS sequence matrix comprised 620 characters, of which 13 were indels. A total of 190 characters was variable, of which 142 were informative (6 from the indel partition). No polymorphic sites were present in ITS. The final matrices used for analyses can be obtained from supplementary files S1 for plastid and S2 for ITS.

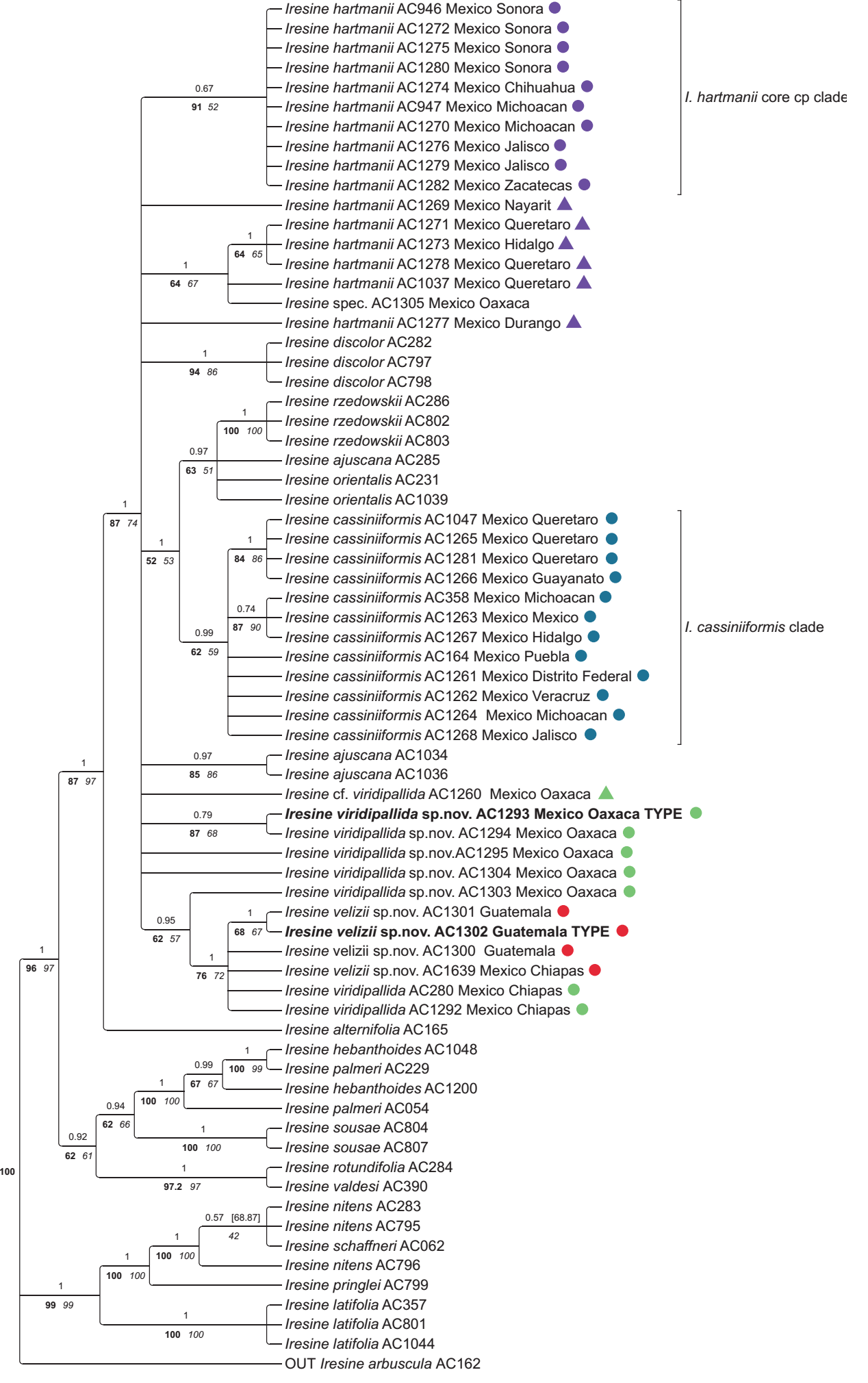

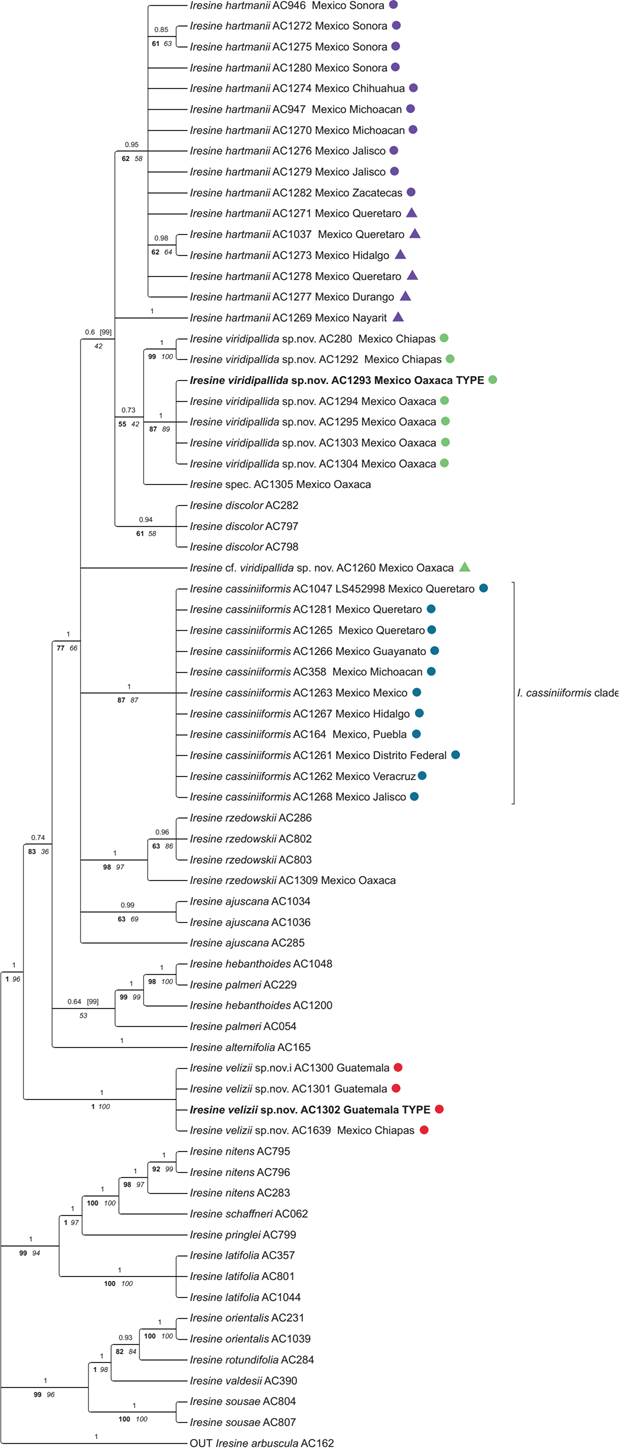

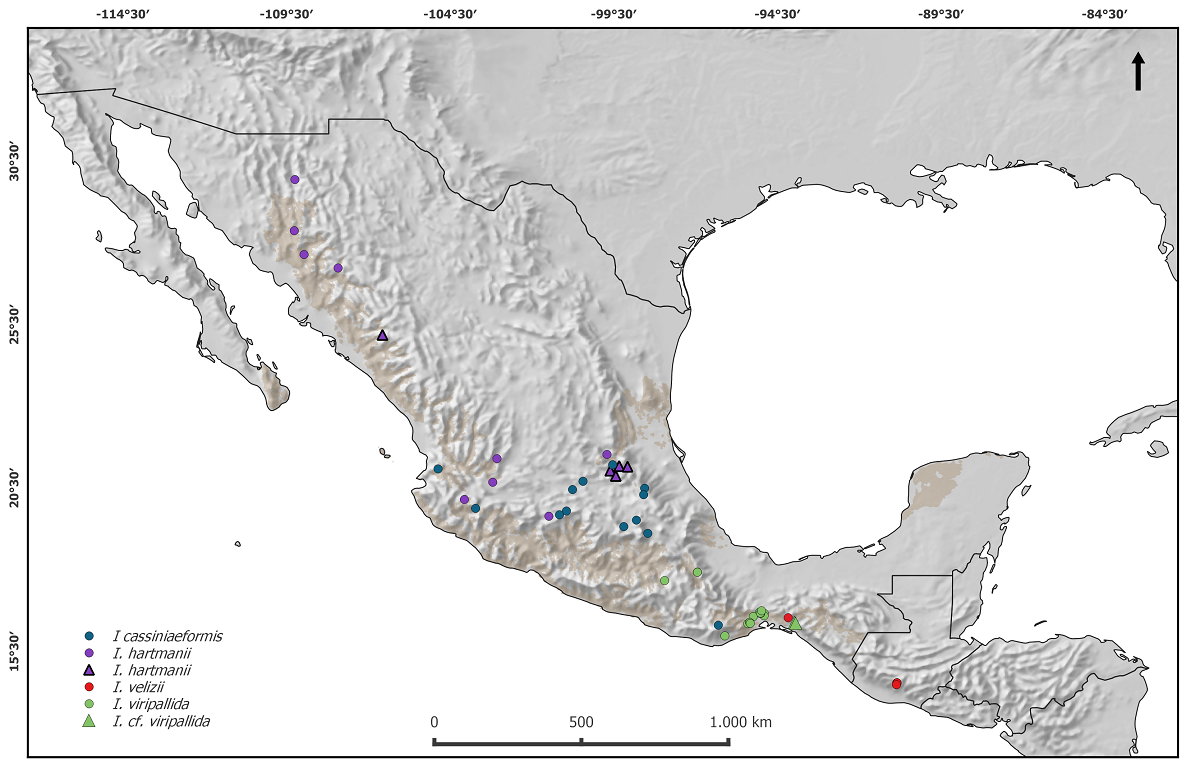

Trees inferred from plastid and ITS data. The trees obtained from all three inference methods (BI, ML and MP) were largely congruent with only slight differences in statistical support for some nodes. The results are shown in Figures 1-2 for the plastid partition and nuclear ITS, respectively. Both trees depict three major lineages within Iresine subclade A (A1, A2, A3). The combined matK-trnK-psbA + rpl16 + trnLF tree reveals I. alternifolia as sister of all remaining taxa in subclade A1. It depicts a clade of the individuals of I. hartmanii from the dry areas of Central to North-Western Mexico (“I. hartmanii core clade” in Figure 1 (plastid); purple circles in distribution map of Figure 3), and a clade of individuals of I. cassiniiformis that is also recovered with ITS in the same composition (“I. cassiniiformis clade” in Figures 1-2 (plastid, ITS); blue circles in map of Figure 3). On the other hand, the ITS tree depicts a more inclusive clade of I. hartmanii (Figure 2), whereas the south-eastern individuals of this I. hartmannii clade in the ITS tree are resolved in an own sublineage based on plastid sequences (Figure 1, “I. hartmanii SW individuals”; purple triangle in distribution map of Figure 3) that appears in a polytomy of the I. hartmanii core cp clade. And the same applies to sample AC1277 (I. hartmanii from Durango). The individuals of morphotype XXXIV from Oaxaca are part of a broad polytomy in the plastid tree, whereas one individual of morphotype XXXIV from Oaxaca (AC1303), and the individuals from Chiapas are resolved in another sublineage of this assembly paraphyletic to the individuals from Guatemala (Figure 1). The ITS tree reveals a weakly supported lineage of all morphotype XXXIV individuals from Oaxaca plus two from Chiapas, whereas the three individuals from Guatemala and one individual from Chiapas (AC1639) appear as a highly supported isolated clade as sister to the remainder of all other individuals in subclade A1.

Figure 1 Phylogenetic relationships of Iresine clade A based on the combined matrix of the plastid regions matK-trnK-psbA + rpl16 + trnLF. The 50 % majority rule consensus tree from Bayesian analysis is shown with Posterior Probabilities (PP) above branches, and jackknife values from maximum parsimony inference (left, bold) and bootstrap values from maximum likelihood inference (right, italics) plotted below. Graphic symbols next to terminals represent the different entities of the Iresine cassiniiformis-I. hartmanii alliance as shown in the distribution map.

Figure 2 Phylogenetic relationships of Iresine clade A based on nuclear ITS sequence data. The 50 % majority rule consensus tree from Bayesian analysis is shown with Posterior Probabilities (PP) above branches, and jackknife values from maximum parsimony inference (left, bold) and bootstrap values from maximum likelihood inference (right, italics) plotted below. Graphic symbols next to terminals represent the different entities of the Iresine cassiniiformis-I. hartmanii alliance as shown in the distribution map.

Figure 3 Geographical distribution of specimens of the Iresine cassiniiformis-I. hartmanii alliance included in the phylogenetic analysis (graphic symbols can also be found in the tree figures): Iresine hartmanii core clade (purple circles), specimens representing possible ancestral types of I. hartmanii (purple triangles), I. cassiniiformis (blue circles), I. viridipallida sp.nov. (green circles), I. velizii sp.nov. (red circles).

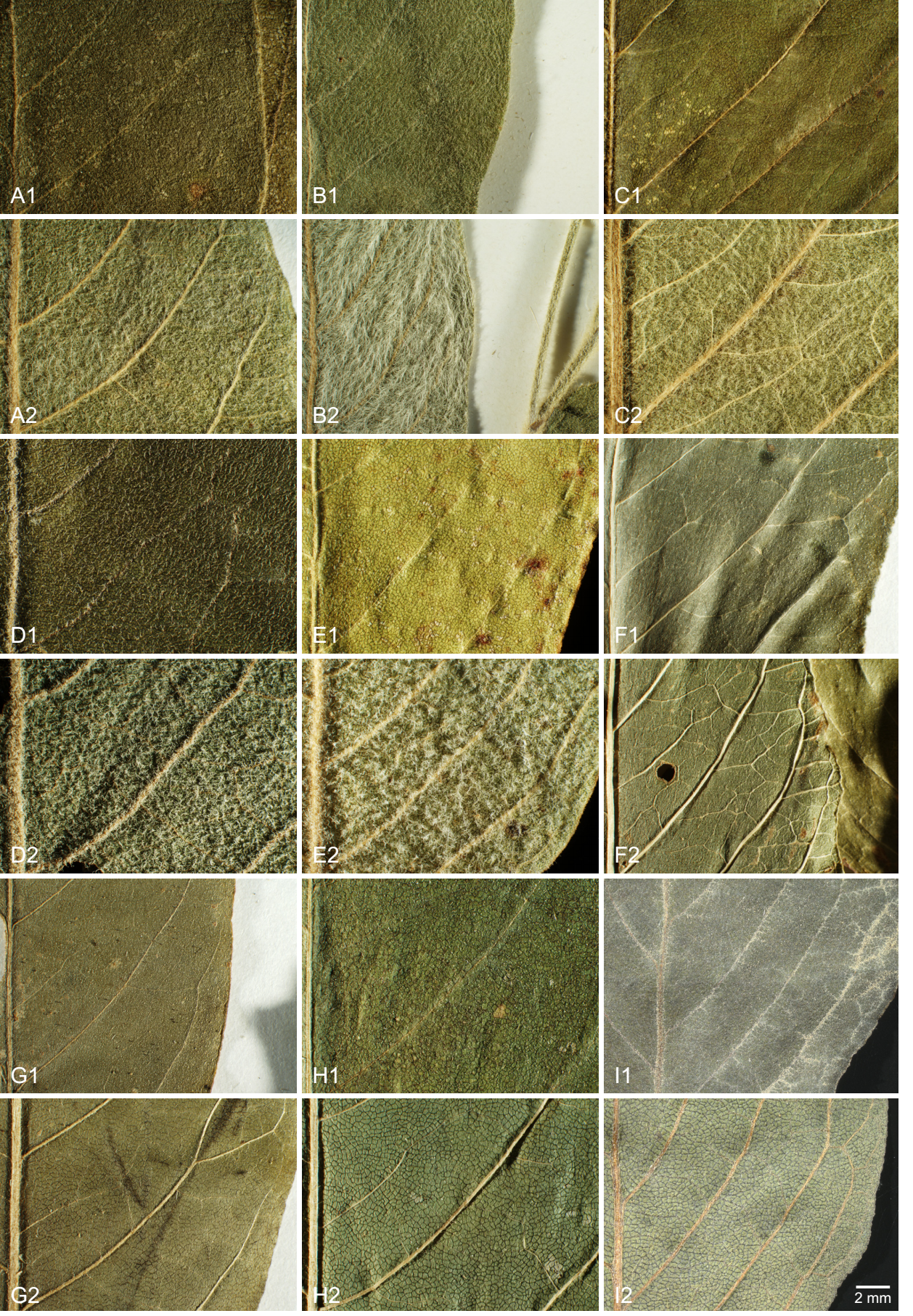

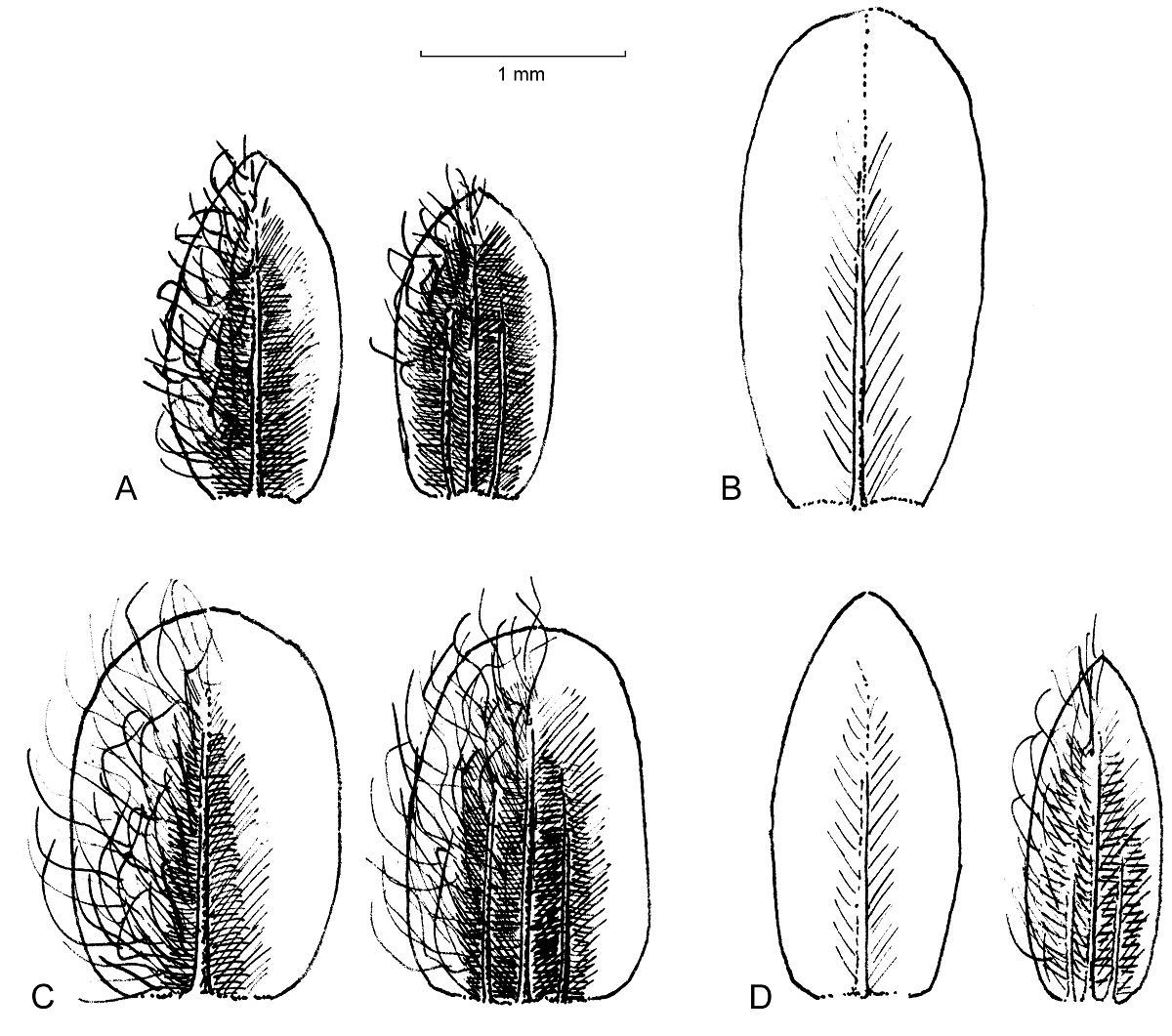

Morphology. The leaf venation and indumentum from a representative set of specimens is illustrated in Figure 4. The lower leaf surfaces in the core clade of I. hartmanii are covered by a dense, more or less appressed indumentum of white uniseriate trichomes whereas the upper surface is rather sparsely pubescent with shorter, uniseriate trichomes. AC1278 is intermediate (upper surface glabrous). Iresine cassiniiformis densely pubescent below (not appressed). All specimens from Oaxaca and Chiapas (Figure 3F-H) are glabrous or almost so from both sides with very prominent midvein and first level lateral vein; this applies also to the specimen from Guatemala (Figure 3I) but lateral veins are closer to each other.

Figure 4 Microphotographs of upper (images annotated with “1”) and lower (images annotated with “2”) leaf surfaces in selected individuals of Iresine as represented in the molecular phylogeny. Iresine hartmanii from the core plastid lineage: A (W. Trauba 98-11, Sonora, AC1280) and B (V.W. Steinmann 93-152, Sonora, AC1275; possible ancestral types of I. hartmanii from the southern border of the species’ range: C (H. Rubio 2667, Queretaro, AC1278); Iresine cassiniiformis: D (J. de la Luz Castaneda L. 120, Guanajuato, AC1966) and E (H. Flores Olvera 1352, Hidalgo, AC1967); Iresine viridipallida sp.nov.: F (L. Alvarado C. 1216, Chiapas, AC1292) and G (R. Torres C. 4212, Oaxaca, staminate specimen, AC 1293, type) and H (J. Pascual 1048, Oaxaca, AC1303); Iresine velizii sp.nov.: I (M. Veliz 12708, Guatemala, AC1302, type).

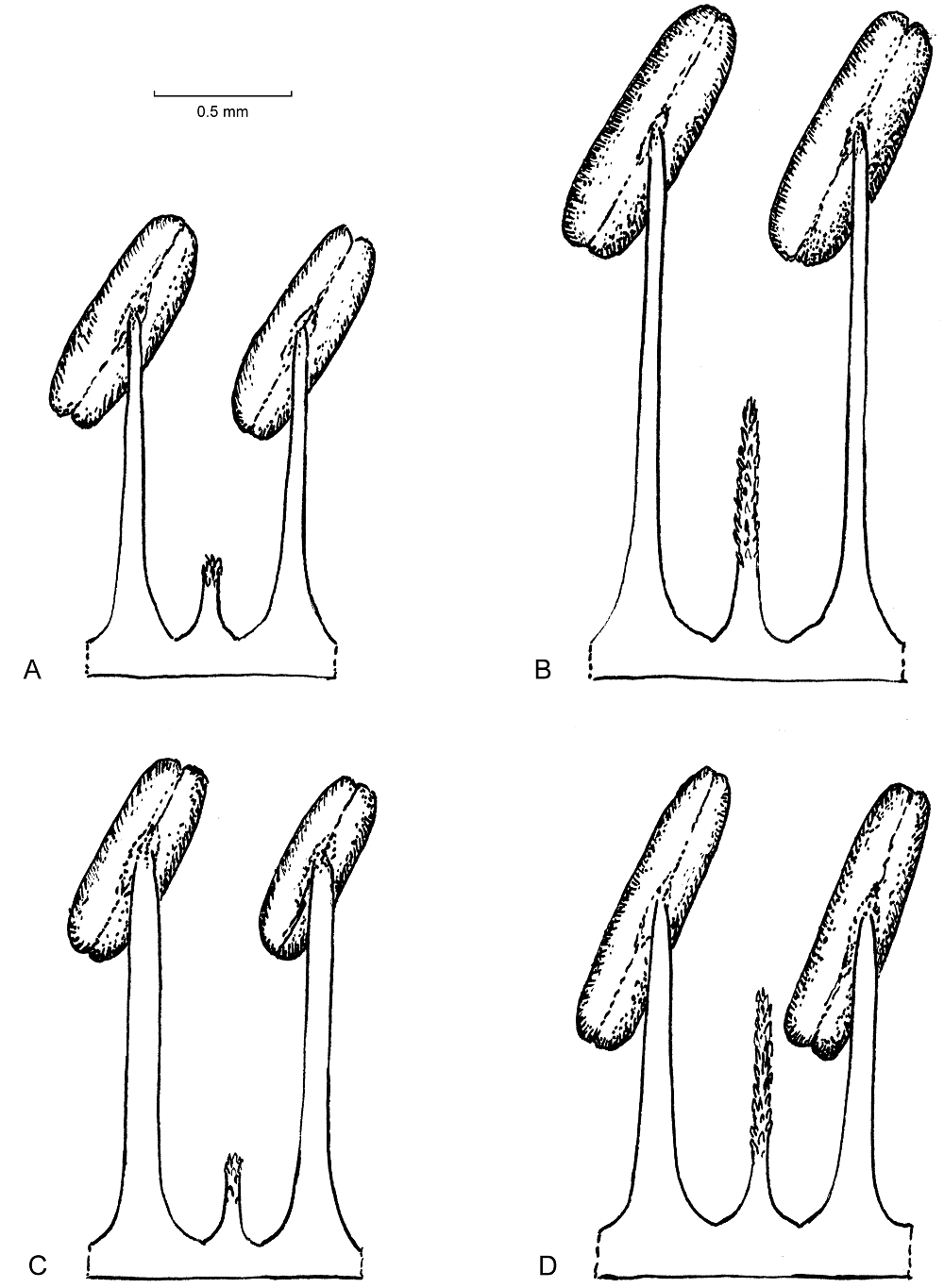

The morphology of tepals is shown in Figure 5, presenting one of the two outer tepals in staminate and pistillate individuals. Tepals of pistillate plants are 3-veined, although weakly so in I. cassiniiformis (Figure 5D). In comparison to I. viridipallida (Figure 5A and see detailed description in the taxonomic treatment part) the tepals of I. hartmanii (Figure 5C) are more broadly ovate with a rounded to obtuse tip and a broad hyaline margin. The inner part is scarious and green in colour, laterally with a little thinner pale brown part. The abaxial surface is densely covered by uniseriate trichomes. Contrary to the other species, tepals of staminate pants in I. cassiniiformis (Figure 5D) are completely glabrous and cream in color, the scarious texture gradually becomes thinner to the margin. Tepals of pistillate flowers differ by being lanceolate and also a gradually thinner tissue towards the margin with an indistinct hyaline margin. Tepals of staminate plants of I. velizii (Figure 5A and see detailed description in the taxonomic treatment part) are the largest in the species compared, slightly obovate in shape and also completely glabrous.

Figure 5 Outermost tepals of staminate (left) and pistillate (right) individuals in standard magnification. A: Iresine viridipallida sp.nov. (R. Torres C. 4212, AC 1293, type); B: I. velizii sp.nov. (staminate M. Veliz 12708, AC1302, type); C: I. hartmanii (staminate P. Tenorino L. 18649, AC1274, pistillate W. Trauba 11-98, AC1280); D: I. cassiniiformis (staminate de la Cruz Castaneda 120, AC1266, pistillate E.J. Lott 756, AC1268).

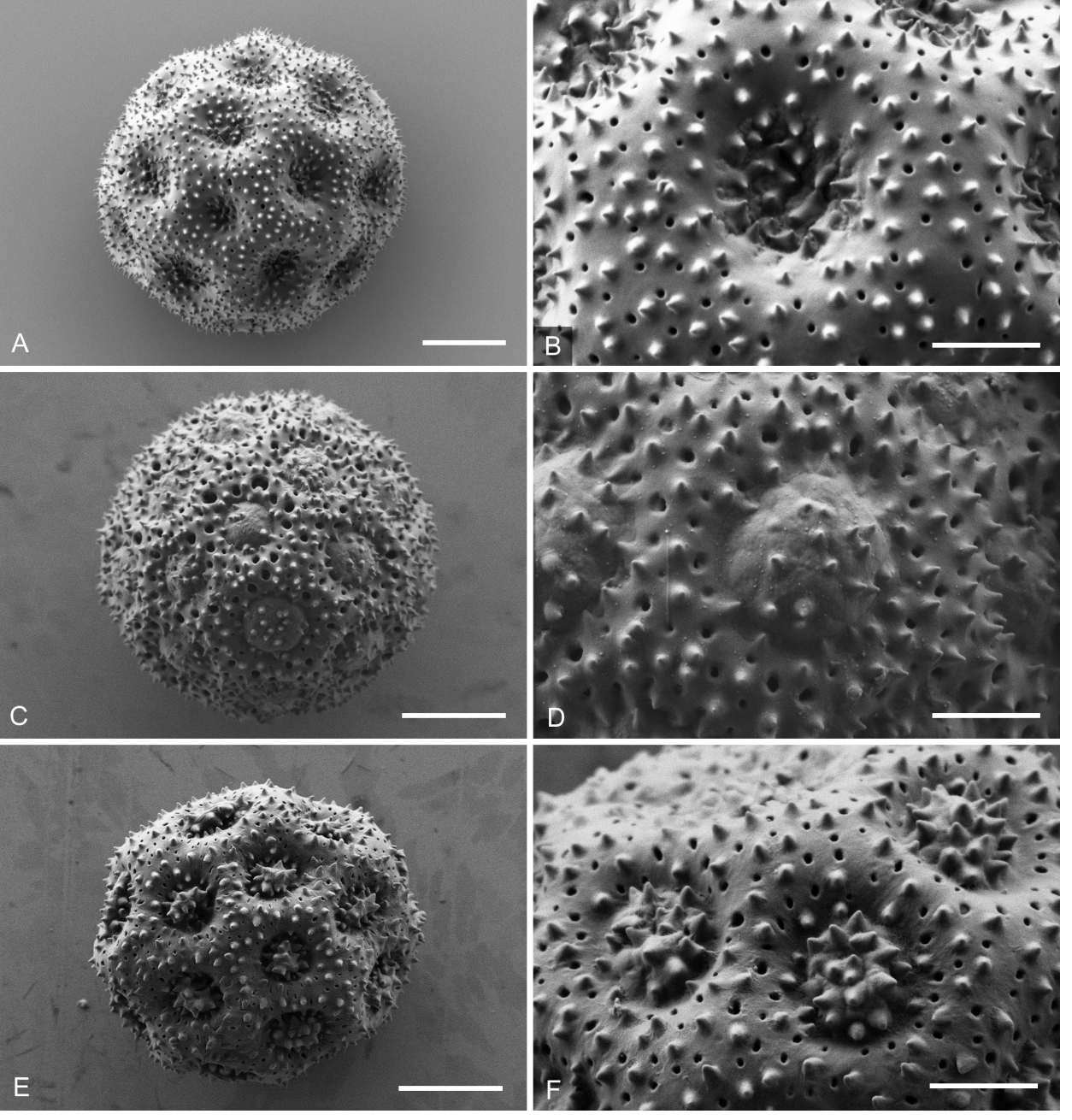

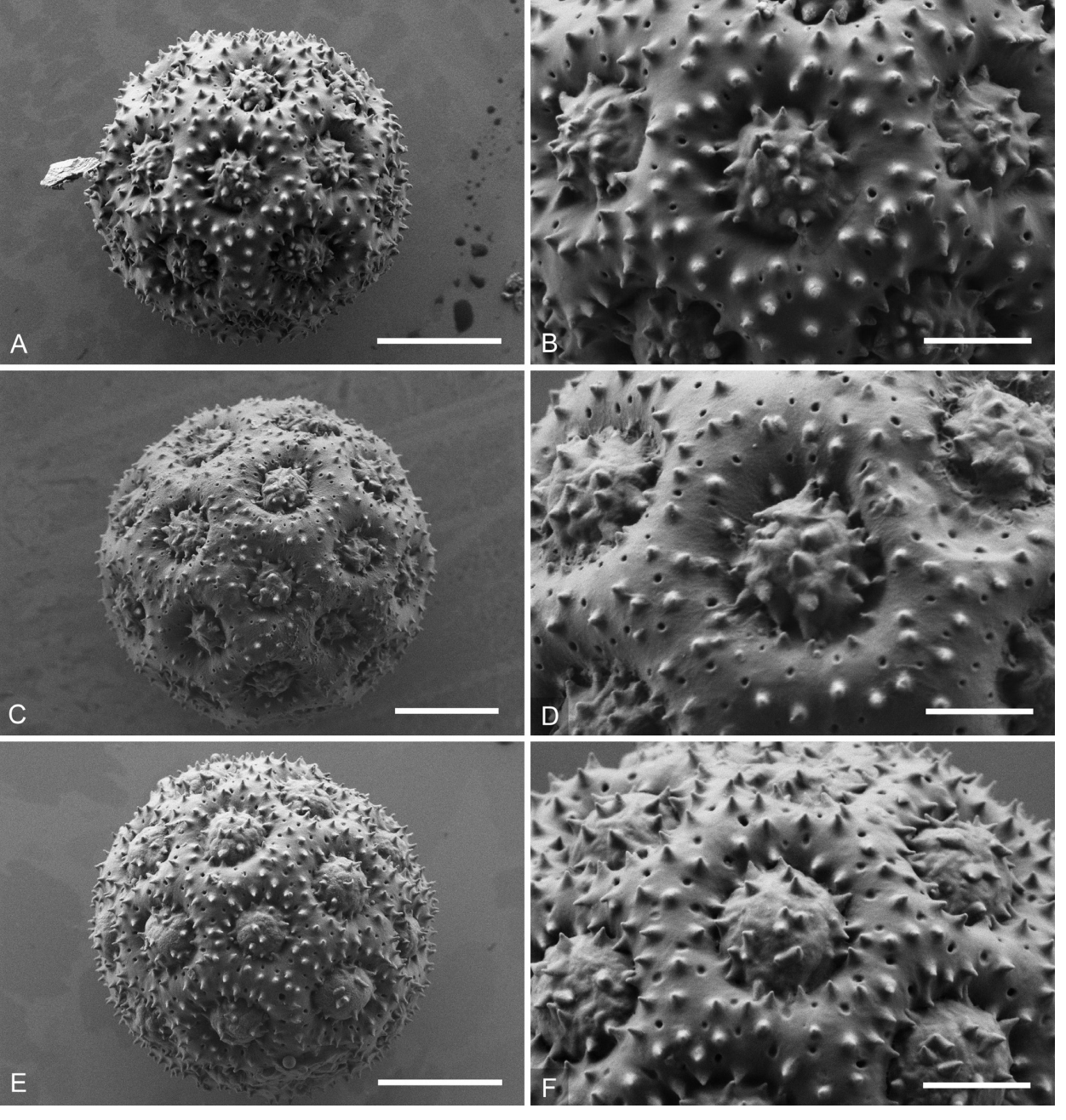

The morphology of pollen grains and details of the apertures and tectum in standard magnification is illustrated in Figures 7 and 8. Like in other species of Iresine pollen of the investigated samples is pantoporate with broadly vaulted mesoporia and a spinulose, perforate tectum. The apertures possess evenly distributed ektexinous bodies in the form of microspines (Iresine-type pollen, see Borsch et al. 2018). Iresine viridipallida (Figure 8A, B, E, F) differs by slightly higher microspines than the other samples. These are particularly smaller in I. velizii (Figure 8C, D) which also has fewer and smaller tectum perforations. Microspines are smaller and more frequent in pollen of I. hartmanii (Figure 7 A, B) as compared to I. viridipallida, what seems to be stable across different flowers (the grain illustrated here is from the same specimen Tenorio 18649 as in Figure 4H of Borsch et al. (2018) but from a different flower and shows identical features). Pollen characters therefore differ to some extent in the two species to be recognized here. However, this variation is rather quantitative and the scarce currently available material (one staminate specimen with mature flowers of I. velizii; except one the specimens from the core cp clade of I. hartmanii are pistillate plants) limits its statistical analysis.

Figure 6 Androecium morphology. A: Iresine viridipallida sp.nov. (R. Torres C. 4212, AC 1293, type); B: I. velizii sp.nov. (M. Veliz 12708, AC1302, type); C: I. hartmanii (P. Tenorino L. 18649, AC1274); D: I. cassiniiformis (de la Cruz Castaneda 120, AC1266).

Figure 7 Scanning electron photomicrographs of pollen grains and corresponding apertures (the latter in standard magnification). A, B: Iresine hartmanii (P. Tenorino L. 18649, AC1274) from the same specimen as in Borsch & al. (2018) paper, but a different pollen grain; C, D: Possible ancestral type of I. hartmanii (G. Flores F. 1800, AC 1269); E, F: I. cassiniiformis (de la Cruz Castaneda 120, AC1266). Scale = 4 µm for whole grains and 1.5 µm for apertures.

Figure 8 Scanning electron photomicrographs of pollen grains and corresponding apertures (the latter in standard magnification). A, B: Iresine viridipallida sp. nov. (R. Torres C. 4212, AC 1293, type); C, D: I. velizii sp.nov. (M. Veliz 12708, AC1302, type); E, F: I. viridipallida (L. Alvarado C. 1160, AC1292). Scale = 4 µm for whole grains and 1.5 µm for apertures.

Discussion

Phylogenetic relationships and species diversification in Iresine. Considering overall relationships, the genus Iresine is constituted by two major clades (A and B in Borsch et al. 2018). The first of them largely represents a radiation of species in Mexico with the exception of I. latifolia that extends throughout Mesoamerica (Borsch 2001), whereas clade B entails mostly Mesoamerican (I. arbuscula, I. nigra Uline & W.L.Bray) or even widespread neotropical taxa (I. angustifolia Euphrasén and the I. diffusa species complex). Clade A was shown to have three internal clades (A1, A2, A3 in Borsch et al. 2018). The phylogenetic trees presented here show that all samples added here were resolved within clade A1 which remains well supported as monophyletic in plastid (Figure 1) and ITS trees (Figure 2). Most strikingly, the first branch of clade A1 in the ITS tree (Figure 2) is now constituted by three samples from Guatemala (AC1300, AC1301, AC1302) and one from Chiapas (AC1639) which were not sampled previously. The plastid tree comprises them in a larger subclade including further samples from Chiapas and Oaxaca (Figure 1). Overall phylogenetic analyses of the genus Iresine (Borsch et al. 2018) already revealed a small terminal clade of I. cassiniiformis, that included three samples (AC164 and AC358, and AC1047) the latter of which was annotated as morphotype XXXIV, from Queretaro) but was confirmed to be I. cassiniiformis based upon more detailed morphological examination in line with the more extensive molecular data presented here. The weekly supported subclade that indicates a common ancestry of the plastid genome of I. cassiniiformis with I. orientalis and I. rzedowskii (see Figure 2 in Borsch et al. 2018) is also revealed in this investigation with more extensive taxon sampling (Figure 1).

Ortuño Limarino & Borsch (2020) inferred a Miocene origin of Iresine clade A, whereas Di Vincenzo et al. 2018 only sampled I. alternifolia, I. cassiniiformis, and I. palmeri that in fact represent subclades A1 and A2 of clade A, so that their much younger crown group age of 7 Ma of an “Iresine” crown group at the Miocene/Pliocene boundary is caused by sampling differences at the species level, but still corresponds with divergence times in Ortuño Limarino & Borsch (2020). Therefore, the diversification of the largely Mexican Iresine clade A started at a time when the Mexican Transvolcanic Belt (Mastretta-Yanes 2015) and many drier habitats of the Mexican highlands began to form. It is possible that early branching lineages in subclade A1 were adapted to more or less humid forest habitats including the two new species recognized here, with a subsequent northward diversification with different lineages arising in drier conditions, with desert species like I. hartmanii. Future research and increased resolution of relationships will be needed to further illuminate this.

An evolutionary scenario for the members of Iresine in Oaxaca, Chiapas and Guatemala hitherto considered as I. cassiniiformis- and I. hartmanii-like morphotypes. In the plastid and nuclear trees (Figures 1, 2) the specimens from Oaxaca and Guatemala hitherto annotated as I. cassiniiformis, I. hartmanii or as morphotype XXXIV are found distinct from both the I. cassiniiformis and I. hartmanii sublineages. Most of the plants from Oaxaca (AC1293, AC1294, AC1295, AC1303, AC1304; annotated with green circles on trees and the map in Figure 3) come from elevations of 480-680 m where they grow in tropical deciduous forest (selva baja caducifolia). In the following they are called “I. viridipallida”. Their morphology is relatively uniform, with lax, mostly leafless synflorescences in pistillate and staminate plants, and flowers arranged in distinct heads. In this respect they resemble specimens of the core I. hartmanii clade, but contrary to those, the shape of flower heads is never cylindrical but subglobose and the number of flowers is much less. Cauline leaves (Figure 4) differ from I. cassiniiformis and I. hartmanii by being glabrous on both sides with prominent veins, like in other species growing in semigreen or evergreen forests (e.g., I. arbuscula, I. nigra). The tepals (Figure 5) are similar to I. hartmanii with three veins and a distinct hyaline margin but slightly shorter (outer around 1.4 mm) and with a less dense indumentum, so that the greenish to pale brown color of the tissue between the three veins becomes visible. Individuals of I. cassiniiformis on the other hand have much larger (outer 1.9 mm), one-veined, entirely glabrous and cream-colored tepals (Figure 5D). Also, the individuals of the I. viridipallida lineage differ by very short interstaminal appendages (Figure 6A). The two plants from Chiapas (AC280, AC1292) also come from lower elevations with tropical deciduous forest. The morphology of their staminate flowers deviates from the flowers of individuals from Oaxaca by longer free filament parts (1.2 mm) and interstaminal appendages reaching to about half their length, slightly longer 3-veined tepals (1.8 mm for the outer) with a scarious pale brown inner part with an indumentum of short uniseriate trichomes concentrated only near the apex. But their inflorescences have the lax and leafless architecture with well-delimited subglobose paracladia typical of I. viridipallida (specimens annotated with green circles) and plants possess the glabrous cauline leaves with prominent veins. All the I. viridipallida specimens from Oaxaca and the two specimens from Chiapas (AC280, AC1292) appear in a single subclade of the ITS tree (Figure 2), albeit only weakly supported.

The plants from Guatemala (AC1300, AC1301, AC1302) and a further specimen from Chiapas (AC1639) (all four annotated with red circles in Figures 1-3) constitute a very distinct and unique lineage in Iresine that is resolved based on ITS as having branched prior to the diversification of Iresine clade A1 (Figure 2). Morphologically, these plants are different by large staminate flowers with cream colored, scarious, completely smooth tepals that are 2.1-2.2 mm (outer) and 2.0 mm (intermediate and inner) long. Also, the filaments are long in comparison with the allied species (1.4 mm, free part) and interstaminal appendages reach about half their length (Figure 6B). In this respect, the flowers resemble those in I. cassiniiformis (Figure 6D), although in the latter the interstaminal appendages are even longer, reaching to two thirds of the filament’s length. So far, pistillate individuals are not known. The inflorescences are richly branched and up to 30 cm tall, with numerous cauline-like leaves and poorly defined flower-heads.

The hard incongruence between plastid and nuclear trees points to a reticulate origin of the ancestor of the four samples in this lineage. The fact that the plastid haplotypes of the plants from Guatemala and specimen AC1639 from Chiapas are nested as one terminal subclade among specimens of I. viridipallida from Oaxaca and Chiapas in the plastid tree points to an I. viridipallida-like maternal ancestor. In Guatemala the plants grow at elevations between 1,900-2,100 m at the Volcan Acatenango and also the specimen from Chiapas (AC1639; Breedlove 31450) is from montane rainforest at 1,600 m on Cerro Baul (Municipio Cintalapa, close to the border with Oaxaca). It was thus collected about 400 km northwest of the Guatemala site but in proximity to the sites in Chiapas where the two specimens AC280 and AC1292 (also annotated by green circles; Figures 1-3).

Based on the plastid tree I. viridipallida is paraphyletic to I. velizii but the ITS ribotypes of that species are unique and represent an isolated lineage in Iresine. No polymorphic sites in ITS were evident indicating strong concatenation either towards the paternal parent or if intermediate, the paternal parent had an even more distant ribotype. Strongly biased concerted evolution in ITS is also known from other plants (e.g., Wendel et al. 1995, Winterfeld et al. 2009). Our hypothesis of such a reticulate speciation event suggests that the paternal ancestor is uncollected or even extinct, with the consequence that its possibly also distinct plastid haplotype is now also extinct. The maternal parent came from the I. viridipallida gene pool, which is rather diverse considering both, plastid haplotypes and ITS ribotypes (Figures 1, 2). The high similarity of these sequences in the Guatemala plants and the specimen from Cerro Baul indicates a single reticulation event with subsequent dispersal. Considering the current small overlap of plants belonging to the I. viridipallida lineage and the I. velizii lineage, this reticulation event could have occurred in the area of the Isthmus de Tehuantepec. Here it fits to vicariance patterns found across the isthmus of Tehuantepec (Ornelas et al. 2013), although with a more complex speciation history than simple allopatric differentiation. However, it is remarkable that no collections have been reported for most of the Sierra Madre de Chiapas south to Guatemala, although there are similar pine-oak-liquidambar forest habitats between 1,200 and 2,000 m (Miranda 2015).

Iresine viridipallida is a morphologically consistent entity that includes nested the I. velizii plastid haplotypes. The plastid tree (Figure 1), however, does not resolve all specimens in a clade but this is the case in the nuclear ITS tree (Figure 2), further supporting its recognition as a distinct species in addition to morphology. Further sequencing of complete plastid genomes will need to test if they have also a common ancestor as our current sampling of DNA characters does not yet comprise enough information. Partial sorting may have happened in the mountain ranges of Oaxaca, resulting in uniform ITS ribotypes (AC1293 = type specimen, AC1294, AC1295, AC1303, AC1304), whereas the two Chiapas specimens appear together exhibiting slightly different ribotypes (Figure 2) in line with slight deviations of some morphological character states. Based on the currently available data, we delimit I. viridipallida as a species that comprises populations from Oaxaca and Chiapas. It may have arisen from a single ancestor, with the observed infraspecific variation representing patterns of geographic differentiation. The type specimen was selected from the gathering of R. Torres C. 4212 from Oaxaca because pistillate and staminate individuals were available of this same gathering. While assuming that one ancestral population provided a captured chloroplast for another hybrid speciation event that led to I. velizii, we do not see evidence for para- or peripatric speciation because this hybridization included phylogenetically distant parents.

Species limits of I. cassiniiformis and I. hartmanii. As indicated by our phylogenetic trees from both the plastid and nuclear compartments I. cassiniiformis is a monophyletic species (Figures 1, 2) that occurs in the central Mexican highlands from Jalisco to Puebla at elevations from 1,700 to 2,500 m NN, and in this circumscription the species has a center of distribution in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (TMVP). In the North-West it extends to Aguascalientes and Zacatecas (specimens in HUAA and HZAC) based on inspection of morphology. The synflorescences are leafless and densely branched up to the 3rd order and flowers appear in little defined heads, thus differing from the other species discussed here. Leaf undersurfaces are densely pubescent (Figure 4D, E) with uniseriate trichomes, which are not appressed. Contrary to I. hartmanii and I. viridipallida the tepals of staminate flowers (Figure 5) are 1-veined, scarious in texture without a distinct hyaline margin, cream-coloured and somewhat larger (outer 1.9 - 2.5 mm). In pistillate plants the outer tepals (Figure 5D) are much narrower and lanceolate and weakly 3-veined with an indistinct hyaline margin, whereas in I. hartmanii these tepals are broadly ovate to boat-shaped, with rounded apex and possess a distinct and broad hyaline margin (Figure 5C). Plants of I. cassiniiformis collected in Puebla at the end of the dry season (AC164) show that cauline leaves are mostly falling off during the dry season and then new leaves grow with the beginning rains. Further research will need to show, if this is a consistent and distinct pattern in this species. It will be interesting to see to what extent the patterns of infraspecific genetic diversity of the species are influenced by landscape connectivity versus isolation in individual mountain areas, which have fluctuated in the TMVP during the Pleistocene (Mastretta-Yanes et al. 2015). Iresine cassiniiformis was collected by Alwin Aschenborn (1839-1841) in Mexico without further locality data (Nees ab Esenbeck & Schauer 1847). Morphologically the type (FR barcode FR-0036366!) fits to the specimens in the I. cassiniiformis clade.

Iresine hartmanii comprises a clade of individuals confined to the northern deserts that is well supported by Bayesian posterior probabilities but less in the other inference methods and annotated as “I. hartmanii core cp clade” in Figure 1. These individuals have a synapomorphic “AC” close to the downstream end of rpl16 intron, which was not discovered in Borsch et al. (2018), since one of the two sequences of the two samples of I. hartmanii included there ended prior to this position, rendering this mutation as potentially variable but uninformative. Morphologically, the individuals of the core cp clade of I. hartmanii (annotated with purple circles) stand out by cylindrical flower heads with many densely aggregated flowers, with a dense indumentum, also abaxially on tepals (Figure 5C) in both pistillate and staminate plants. Individuals of this core clade are so far reported from Chihuahua, Jalisco, Michoacán, Sonora and Zacatecas (Figure 1). Morphologically similar specimens from Aguascalientes (in HUAA) still need to be sequenced. The type specimen of I. hartmanii is from Sonora (Hartman 232, US barcode 00102825!; Uline 1899) and also fits this morphology. The ITS tree depicts a more inclusive clade, comprising the same individuals of I. hartmanii from the desert regions but also specimens from Hidalgo (AC1273) and Querétaro (AC1037, AC1271, AC1278) which are found in an own subclade in the plastid tree that appears in a polytomy with the core clade of I. hartmanii, I. cassiniiformis, I. discolor and others. The specimens (annotated with purple triangles) are morphologically intermediate to I. cassiniiformis (AC1278 leaf Figure 4C), occur directly south of the desert zone, either representing ancestral types in the speciation of I. hartmanii or a result of introgression from I. cassiniiformis. Specimen AC1269 from Nayarit fits the morphology of tepals of I. hartmanii although they are rather large (outer 1.8 mm), whereas the filaments are shorter (0.6 mm free part) and interstaminal appendages 0.3 mm (a little bit more similar to I. cassiniiformis). Leaves are only sparsely pubescent with prominent veins (like in I. pallidifolia), and the plant was collected also in dry forest at 500 m. It is therefore also annotated with a purple triangle in this group.

If the Iresine hartmanii core clade is seen as a derived lineage adapted to the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Desert regions, our hypothesis of the presence of ancestral genotypes in the area south of the Coahuila filter barrier would be in line with the idea of transition zones in the evolution of the warm deserts (Hafner & Riddle 2011). In the case of Grusonia (Cactaceae) an age of the crown group of Chihuahuan and Sonoran species was inferred at 3.7 Ma (Bárcenas & Hernández 2022). Contrary to these cacti, Iresine hartmanii occurs more at the margins of the deserts but will thus constitute a complementary example from plants for better understanding biogeographical history of the desert flora.

Based on the phylogenetic analyses and morphological evidence presented above, we describe two new species within the Iresine cassiniiformis – I. hartmanii alliance.

Iresine viridipallida Borsch & Flores Olv. sp. nov. (Figures 4, 5, 6 and 8).

Type. Mexico, Oaxaca, Cerro Guiengola al NW de Tehuantepec, 1,110 m, 16° 23' 21.92" N 95° 20' 35.18" O, 27. Nov. 1983, R. Torres C. 4212, AC1293 (Holotype: MEXU barcode MEXU1572668; Isotype: B barcode B 10 1244348).

Diagnosis. (based on staminate plant) - Compared to I. hartmanii, which has broadly ovate outer tepals with rounded apex and a broad hyaline part, the tepals are broadly lancelolate with a distinct and narrow hyaline part and a green center close to the midvein. Filaments are shorter (0.8 mm versus 1.0 mm, free part) and flower heads of inflorescences have fewer flowers (2-4) and are subglobose in shape versus 6-10 flowers and being long cylindrical in I. hartmanii. Cauline leaves are glabrous (or with sparsely scattered uniseriate trichomes) versus densely pubescent in I. hartmanii with slightly appressed uniseriate trichomes).

Description. Treelets up to 4 m, dioecious. Stems upright, richly branched in upper part, solid bark greyish yellow with scarse whitish lenticels. Leaves opposite; petiole 0.6-1.5 cm long; blades lanceolate to ovate-lanceolate, 3.0-9.5 × 1.4-3.4 cm, membranous, with 7-15 pairs of lateral veins, these prominent on the lower surface, base narrowly cuneate, apex acute; glabrous to very sparsely hairy at lower surface on and close to midvein, trichomes simple up to 0.1 mm long. Synflorescences of staminate plants branched up to 2nd order with a dominant principal axis, 8-9 cm high, 7-10 cm wide, the lower 2 to 3 branches of 1st order opposite, the others shifted, the lowermost pair of 1st order branches supported by normally-sized cauline leaves, the others by small bract-like scales, 7-12 (-14) flowers aggregated into subglobose shortly pedunculate paracladia (“heads”), c. 4 mm high and 3 mm wide; terminal parts of synflorescence branches with a moderately dense indumentum of uniseriate up to 0.6 mm long, white trichomes; axes of paracladia densely white-wooly with curved, up to 0.7 mm long uniseriate trichomes. Synflorescences of pistillate plants branched up to 2nd order with a dominant principal axis, 19 cm high, 17 cm wide, the lower 2 to 3 branches of 1st order opposite, the others shifted, all branches supported by small, dark brown scales, (1-)2-4 flowers aggregated into paracladia, 4-5 mm wide when consisting of more than 2 flowers; synflorescence branches with a moderately dense indumentum of uniseriate up to 0.5 mm long, cream-coloured trichomes; axes of paracladia densely white-wooly with 0.4-0.5 mm long uniseriate trichomes. Staminate flowers with bracts almost equaling bracteoles, these reaching less than ½ length of the tepals; bracts pale brown, scarious at base with an inconspicuous midvein, becoming membranous at margin, broadly ovate, 1.1 mm long, obtuse and usually torn in at apex, glabrous; bracteoles thinly membranous to hyaline, broadly ovate, 0.7-0.8 mm long, without midvein, obtuse and usually torn in at apex, glabrous; tepals pale brown to greenish, thinly membranous and translucent at margin and apex, outer ones narrowly ovate, 1.4 mm long, 0.7 mm wide, rounded at apex, midrib prominent in lower half, abaxial surface especially in the lower half with uniseriate, curved, 0.3-0.4 mm long white trichomes, middle and inner ones similar in texture but broadly lanceolate, 1.4 mm long, 0.5 mm wide, acute at apex, midrib prominent almost to apex, the trichomes present dorsiventrally throughout except margins; filaments 0.8 mm long (free part), very shortly fused at base (0.1 mm), appendages of androecial tube filiform-acute, 0.2 mm long, with fine papillae; rudimentary, 0.3 mm high pistils present lacking the stigma branches. Pistillate flowers with equal bracts and bracteoles, reaching to half of the length of flowers, suborbicular, 0.8-0.9 mm long, thinly membranous, pale brown, midvein inconspicuous, obtuse to truncate at apex, glabrous; tepals pale brown to greenish, scarious with a 0.1 mm wide hyaline margin, outer ones narrowly ovate, 1.2 mm long, 0.6 mm wide, obtuse at apex, with 3 prominent veins reaching almost to apex, abaxial surface with a dense indumentum of uniseriate, curved, 0.6-0.8 mm long trichomes, middle and inner ones broadly lanceolate, acute at apex, 1.2 mm long and 0.5 mm wide, similar in texture and indumentum but veins less prominent, at maturity surrounded by a dense tuft of white uniseriate trichomes arising from the pedicel of the flower, exceeding flowers by 2-2.5 times; staminodia not evident, ovary subglobose, about 0.7-0.9 mm, style conspicuous about 0.1 mm, the two stigmas narrowly linear, 0.3 mm long. Seeds egg-shaped, 1.0 mm long, pale brown, smooth.

Pollen spheroidal, 26-28.5 μm in diam., with 26-32 apertures; pores 4.5-5.0 μm in diam., all of equal size, 14-20 well delimited ektexinous bodies, composed of 1-3 (then at base confluent) cone-shaped spinules with acute tips like those on mesoporia, well separated and evenly spaced; mesoporia broadly vaulted, 3.2-5.4 μm wide, tectum punctate, with round, slightly anulopunctate perforations 80-170 nm in diam., 30-35 perforations per 10 μm2, evenly spaced, spinules cone-shaped with acute tips, 300-350 nm high, 250-300 nm in diam. at base, with 36-60 spinules per 10 μm2, evenly spaced.

Phenology. Flowering and fruiting from October to March.

Distribution and ecology. Iresine viridipallida occur in low to mid elevation (190 to 1,100 m) deciduous or rarely semi-evergreen tropical forest in the districts of Juchitán, Huajuapan, Pochutla, Tehuantepec in Oaxaca, and was also once collected in Arriaga in the western part of Chiapas (Figure 3).

Conservation status. The species has been collected between 1986 and 2006 but our own search for it has so far remained unsuccessful. There are no data about the frequency of the plant in the respective forests, nor if it can persist in disturbed or secondary forest. Field work and an examination if more recent gatherings are present in herbaria, for which the formal description in this study may help, are therefore needed to evaluate the conservation status.

Eponymy. The name is derived from the distinctly green central parts of tepals in both staminate and pistillate flowers, which otherwise appear pale brown due to the less dense indumentum compared to I. hartmanii.

Additional specimens seen. The gathering by R. Torres C. 4212 comprises staminate and pistillate specimens. The holo- and isotypes are the staminate specimen, and the pistillate specimen (B barcode B 10 1244349) can serve as paratype. All other material examined is listed in Supp. mat. 1 as it is also included in the molecular phylogenetic analysis.

Iresine velizii Borsch & Flores-Olv. sp. nov. (Figures 4, 5, 6 and 8).

Type. Guatemala, Sacatepéquez, Volcán de Acatenango, 1,950 m, 14° 32' 1.57" N 90° 50' 27.90" O, M. Veliz 12708, AC1302 (Holotype: MEXU barcode MEXU1227790; Isotype: BIGU).

Diagnosis (based on staminate plant). Iresine velizii differs from I. cassiniiformis by longer (2.1 mm), slightly obovate outer tepals that are rounded at apex (1.7-1.8 mm, and lanceolate with acute apex in I. cassiniiformis) and longer (1.4 mm, free part) stamens (0.7-0.8 mm in I. cassiniiformis). Compared to I. hartmanii and I. viridipallida the tepals are completely glabrous and lack the green to pale brown thicker central part. Cauline leaves are glabrous versus densely pubescent in I. hartmanii with slightly tufted uniseriate trichomes in I. cassiniifomis, at least on the lower surface.

Description. Treelets up to 4 m, dioecious. Stems upright, solid bark greenish brown without apparent lenticels. Leaves opposite; petiole 0.0-1.2 cm long; blades oblanceolate to obovate, 1.5-9.5 × 0.5-4.0 cm, membranous, with 3-5 pairs of lateral veins, these prominent on the lower surface, base narrowly cuneate, apex acute; glabrous to very sparsely hairy at lower surface on and close to midvein, trichomes simple up to 0.1 mm long. Synflorescences of staminate plants branched up to 3rd order with a dominant principal axis, (2-)3-8 (-12) flowers aggregated into more or less subglobose pedunculate paracladia , c. 4 mm high and 5 mm wide, condensed towards terminal parts and there often sessile; synflorescence branches with a dense indumentum of uniseriate 0.2-0.4 mm long, cream-colored trichomes; axes of paracladia densely white-wooly with curved, 0.3-0.5 mm long uniseriate trichomes.

Synflorescences of pistillate plants not known. Staminate flowers with bracts slightly shorter than bracteoles, these reaching to about 40 % of the length of the tepals; bracts dark brown, midvein visible in the lower half, membranous, broadly ovate, 0.8-0.9 mm long, acute at apex, glabrous; bracteoles thinly membranous to hyaline, broadly ovate, 1.1-1.2 mm long, without midvein, obtuse at apex, glabrous; tepals pale cream to greenish and slightly scarious in the narrow inner part (0.2 mm along each side of the midvein), thinly membranous and gradually becoming translucent at the broad margin and apex, outer ones slightly obovate and boat-shaped, 2.1 mm long, 1.2 mm wide, rounded at apex, surface glabrous, midrib prominent in lower half, middle and inner ones similar in texture but oblong, 2.0 mm long, 1.1 mm wide, obtuse to acute at apex, midrib prominent almost to apex, glabrous; filaments 1.4 mm long (free part), very shortly fused at base (0.1 mm), appendages of androecial tube filiform, 0.6-0.7 mm long, with fine papillae; rudimentary, 0.3 mm high pistils present lacking the stigma branches with a long gynophore. Pistillate flowers not known.

Pollen spheroidal, 33 μm in diam., with 34 apertures; pores 4.5-5.4 μm in diam., all of ± equal size, 10-22 not so well-delimited ektexinous bodies, well separated and irregularly spaced; mesoporia broadly vaulted to almost flat, 3.0-4.0 μm wide, tectum punctate, with perforations 60-170 nm in diam., round, with 30 perforations per 10 μm2, evenly spaced; spinules cone-shaped with acute tips, 280-300 nm high, 200-250 nm in diam. at base, with 32 spinules per 10 μm2, evenly spaced.

Phenology. Flowering and fruiting from November to March.

Distribution and ecology. Iresine velizii is known from hollows or ravines of Volcán de Acatenango at 1,950-2,100 and volcan Agua (specimen A. Molina R. 21057 in ENCB with flower buds seems to also belong to this entity). It has been collected in Quercus-Pinus forest with Calliandra sp., Carpinus sp., Garrya sp. Heliocarpus sp., Perymenium sp., Phoebe sp., Urera sp., Viburnum sp. A single specimen is also known from Chiapas (D.E. Breedlove & A.R. Smith, in ENCB) from the municipio of Cintalapa close to cerro Baul where it was collected at 1,600 m elevation in Pine-Oak-Liquidambar forest (Figure 3).

Conservation status. Recent observations are only known from Volcán de Acatenango in Guatemala (M. Veliz, pers. comm.) where it seems to form stable populations. The only known record from Mexico dates back to 1973. Field work and an examination if more recent gatherings are present in herbaria are needed to evaluate the conservation status.

Eponymy. The name honours Mario Veliz in recognition of his botanic work in Guatemala, which also yielded important specimens for the country, his contributions to the botany of Guatemala, and his collaboration in the study of the species of Iresine.

Additional specimens seen. The morphological description is based on the type specimen since the other known species are in bud stage. DNA sequence data from specimens M. Veliz 94-3524 (BIGU), M. Veliz 99-7406 (BIGU, MEXU) and D.E. Breedlove & A.R. Smith 31450 (ENCB) contributed to establishing the taxon concept at species level.

This investigation is based on a sampling of specimens that is representative in terms of geographic distribution of putative species as well as morphological variation in the group and takes the currently known specimens for the study group into account that were collected over several decades. Our results underscore that delimiting species requires a representative sampling across the range of putative species and all their close morphological allies or closest relatives, in case already known. The phylogenetic resolution obtained with a multilocus data set from the plastid and nuclear genomic compartment in addition to morphological characters and geographic data has yielded the information to develop hypotheses on how the new species could have evolved, in order to support a clear taxon concept at species level. We argue that such an integrative taxonomic approach is fundamental to make explicit hypotheses on species limits, in particular in morphologically variable species groups. In this context, molecular characters from the type specimens and their placement in the phylogeny (see González Gutiérrez et al. 2013, Flores-Olvera et al. 2016) allow to make taxa at species level testable.

However, resolution in some parts of our trees is limited. One hand, this may be explained by the nature of the ongoing speciation process including reticulate evolution and incomplete lineage sorting, and on the other by the still insufficient signal in our phylogenetic data set. It will be important that sets of character data from the same specimens can be extended in the future, including phylogenomic approaches, and also complemented by data from further specimens and other Mexican herbaria. Our results shown that in order to properly understand species limits, it is essential to sample putative taxa across their range of distribution, which can only be achieved by investigating specimens in herbaria (de Mestier et al. 2023).

Most phylogenetic and phylogenomic analyses published so far have not sampled across species’ ranges, and there may be challenges for some methods that different DNA qualities need to be included from specimens collected over decades. Nevertheless, clear hypotheses on species limits need to be based on dense sampling. On the hand, this investigation shows how important it is to place individual specimens in a phylogenetic or evolutionary context. Thus, phylogenomic analyses need to take that into account when only few specimens for putative species can be included.

The complex species diversity patterns shown here for Iresine may be typical for many Mexican and Central American plant groups, as they reflect the complexity of habitats with their paleoecological and geological history that has and is still providing constraints and opportunities for plant migration and speciation.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.3572.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)