OUR STARTING POINT: JOINING SOCIOLOGY OF IMMIGRATION AND SOCIOLOGY OF SCHOOLS

The schooling of migrant children (those who were born in a country other than the United States) is more commonly approached by researchers specialized in education. They are interested in school success or failure, which they assess by measuring educational achievements and the adequacy of school policies. Yet, they follow the school trajectories of migrant children by metamorphosing their nature. Once in the school, the international migrant children become students belonging to a minority group regardless his/her migratory trajectory and his/her national/regional backgrounds. In other words, children arriving from Guanajuato, Mexico, or Izabal, Guatemala, become magically equals under the same educational category: English Learner Student or Low English Proficiency student. Education researchers artificially separate different aspects of the same phenomenon: a) the arrival of foreign migrant workers including their children who are often also migrants; b) the school enrollment of international migrant children and the educators’ actions on them, and c) the changes on the school dynamics that immigrant children induce. Due to this disconnection between immigration and schooling, educational centered researches do not conceive the changes happening in schools as part of the immigration flux, nor as an influence of migrants on the institutional dynamics of the host society. The categories used in academic and public scripts show the consequences of separating migrant studies from educational research: the same child is a member of a migrant family (1.5 generation o second generation) from one point of view, and an English Language Learner (ELL) struggling in the school trying to succeed, from the other. In fact, “migrant student” is a category only considered valid in the U.S. official educational policy vocabulary when the student is a child of agricultural workers moving across the U.S. (Hamann, 2001); in that official terminology, migrant children are the one who move within the U.S. territory.

As a result of the slipping semantics, the major concern of researchers who investigate school challenges for Latino students (migrants or not) in the United States is not immigration but poverty, spatial segregation, social maladjustments, lack of teacher training, unequal school resources and budgets, language barriers, college transitions and other factors like inadequate policy making decisions that affects school achievement (Suárez-Orozco and Páez, 2002; Gándara and Contreras, 2009; Leal and Meier, 2011; Garcia, 2001; Romo and Falbo, 1996)1. In that well contextualized institutional artifice -i.e. viewing things from the vantage point of schools, and only the schools-, those researchers rarely related what is happening in the schools as part of the incorporation of immigrants into the host society.

The divorce between the study of immigrant incorporation/integration and school responses2 is even more paradoxical because the historical and political functions that schools played in the United States in the past and will continue to play in the near future: “Indeed, in the American context [last decades of XIX Century], schooling and immigration are two profoundly interconnected elements in the process of creating a nation in a society that, unlike other societies, could not draw upon common history and memory, rituals, or language toward this end…The school as a source of alternative authority…was a powerful means by which the second generation (and less frequently younger members of the first generation) came to recognize how their experience differed from that of their parents. In this sense, the school’s role was very different than other institutions such as the variously denominated churches, or the workplace with which the children of immigrants in the nineteenth century were all too familiar” (Fass, 2007, pp. 23, 28). “[During the first decades of the 20th century] Public schools and educational officials, of course, were always interested in using the classroom to inculcate American values and beliefs in the foreign-born and having them abandon their former traits and beliefs which were often perceived to be strange, often radical, and simply undesirable” (Bodnar, 1985, p. 190); “If demography is destiny, the United States is entering a perilous era [the 21st century] and seems perversely engaged in implementing policies that will greatly heighten the threat to the American future... In that new society, the largest minority group will be Latino, three times as large as the present black population… We could reasonably expect that farsighted leaders would be seeking ways and means to weave together the disparate elements of our changing population with the greatest urgency. Nowhere should this effort be more intense than in our schools. Unlike most other industrial societies, the United States has a weak system of social welfare provision…Only the schools exist as a major instrument for bringing the society together…” (Orfield, 1998, pp. 276-277).

Our purpose in this paper is to show how the schools in Dalton and Whitfield, Georgia, became central actors of the incorporation/integration process of immigrant families. In fact, the fastest, most visible, permanently debated migration’s impacts on Dalton and Whitfield communities were those that were related with to school districts. Schools were the arenas where local societies a) negotiate the most durable and legitimate internal changes they must implement to facilitate the reception and integration of immigrants, and b) imagine their future (i. e. what the host society is expecting from immigrants and their families; how much the receiving communities should change to successfully integrate new immigrants). Based on our field experience in this locale and as researchers of new destinations of Mexican immigrants in the United States, we conclude that schools are the arenas where immigrants culturally, socially, linguistically, deeply and subordinately encounter the host society’s own feelings, beliefs, wishes, fears and imaginaries (Tobin et al. 2013). In fact, we were invited primarily to come to Dalton and Whitfield because civic leaders and school officials realized they needed help in the process of preparing schools to serve newcomers (Hamann, 2003).

The school centered-scripts, as we argue in this paper, hide the inextricably web of relations of resistance, domination and accommodation that school actors build in their everyday encounters with immigrant children and parents. Instead, the school centered scripts told us a story of achievements and failures of schools’ goals, like dropout rates, math, reading and writing scores by race/ethnic categories, graduation performances, college enrollment, depriving children of their ontology (i.e. being migrants coming from Latin American countries or children born in the United States whose parents are adult migrants coming from Latin American countries).

In sum, our goal in this paper is to bring together the sociology of schools and the sociology of immigrant’s integration in order to analyze the role played by schools and educators in receiving, accommodating, and incorporating migrant children to the host society in Dalton and Whitfield. We focused on social continuities and discontinuities. Continuities are the attempts of school actors to reproduce their local and regional communities in spite of the immigration and its demographic consequences. Discontinuities are simply the opposite: those irreversible impacts and consequences that immigrants produce.

DRAMATIC TRANSFORMATION OF SCHOOL DEMOGRAPHY

The dramatic changes in enrollment experienced by the school districts of the City of Dalton (DPS) and Whitfield County (WCS) evidenced that the new composition of the student’s body was the consequence of the sudden arrival of immigrants. At that point, nobody could ignore the link between immigration and school transformation. The equation was clear: industrialists hired migrant workers; workers brought their children and enrolled them in schools. During the 1990s, immigrants arrived to the City of Dalton and Whitfield County producing a radical demographic transformation. Many of them came from Mexico and Central America sharing common backgrounds, schooling experiences and language. Some of them have had deep contact with American society in other states of the country like Texas, California, Arizona, Illinois or New York. Most of them reunified their families in Dalton/Whitfield and had the intention to settled permanently, if possible. All of those who took their children with them and came to the area enrolled them in schools.

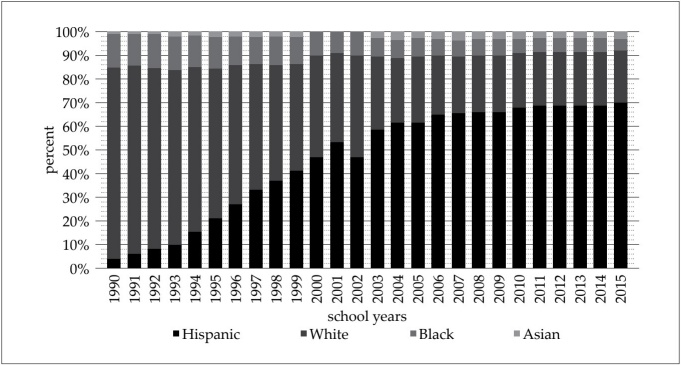

The consequences were immediately visible and seemed irreversible from the outset: in DPS whites were 80 percent of the student body in 1989; this proportion fell down until 21 percent in 2015. This radical percentage change mirrored a decline in absolute numbers: in 1990 there were 3,131 white students enrolled in DPS; by 2015, only 1,684 white pupils were registered in this school system, a result of the flight of middle-whites to area private schools that began around 2000. The percent decline in white student population was -36.4 percent from 1995 to 2015; decreasing on average -1.8 percent annually.

The opposite happened with the Latino student population. The proportion of Latino enrollment grew suddenly between 1995 and 1999 and continued to grow steadily until 2015. Today, the ethnoracial composition of the school population in DPS is much more similar to those one can observe in the school districts of several counties and cities of southern California and south Texas than the school districts of the U.S. historic South.

Roan Street elementary school (PK, KK, 1, 2) became the icon of DPS’s rapid transformation. Located on the East side of the city (the poorer one since the last decades of the XIX century), Roan Street school was dedicated to educate the youngest members of white working class white, a mission that changed around 1990. In 1985, almost 90 percent of the students at this school were classified as whites. In 1995, the presence of white students was still visible with 33 percent of the total enrolment. When we visited this school for the first time in 1997, this proportion had fallen to less than 18 percent. This decline was due to increase of the number of Latino newcomers (indeed “migrant children” and “children of migrants”) in the school and not to a reduction in the number of white children. The total school enrolment in 1995 at Roan Street school was 544 students. In 1997, it was 718.

It is worth noting that the total enrollment in DPS grew consistently since the arrival of Latino immigrants. In 1990, the city’s school district matriculated only 3,876 students. The number of students in 2000 was 5,074. The enrollment increased more than 100 percent in 25 years. In 2015, DPS enrolled 7,858 students. Undoubtedly, the Latino influx represented a demographic bonus for the school district.

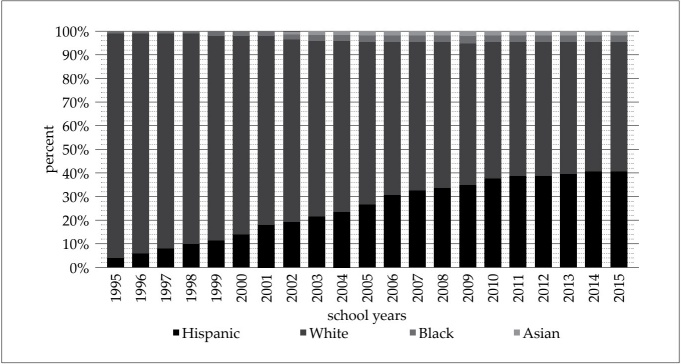

The pace of the Latino (again, “migrant children” and “children of migrants”) enrollment in WCS was slower but consistent. In this school district, only 1 % of the school population was Latino in 1990. By 1995, that proportion remained small compared with that of DPS. However, starting in 2000 the proportion of Latino students progressively increased, reaching 40 % in 2015, with white students representing slightly more than a half of total enrolment. Once again, the arrival of migrant workers with their families induced the absolute growth of the school population at WCS. In 2015, the district enrolled 13 410 students while twenty years before it had only 10 312.

Not surprisingly, the reactions of principals, school officials and teachers went from incredulity to resistance. As Julia -elementary school teacher, born in South Georgia- stated when we interviewed her in February 2010: When the influx began, it was really bad. I didn’t want to work here. To be clear, Julia did not represent the teacher’s anti-immigrant position at all; just the opposite. In fact, during our participation in The Georgia Project initiatives (see below), she was recognized by her peers for being one of the most proactive educators in trying to include and integrate Latino students. She attended twice the Summer Intensive Spanish and Mexican Culture Program offered by the Universidad de Monterrey between 1997 and 2007 (the year when federal and local funds were cut off for this kind of training programs).

Julia’s resistance was understandable if we consider that, when the demographic transformation started in Dalton, nobody had a precise idea of what multicultural education meant, or what transitional bilingual education entailed for schools and teachers, or about the role assigned to schools in integrating foreign non-English speaking students. The exception was the non-Georgian principal of Roan Street School, who had written a Ph. D. dissertation about the values and methods of bilingual education in the United States (Beard, 1996).

Paul, a school teacher in WCS and proud of being one of a few teachers in Dalton/Whitfield area who spoke languages other than English, shared his memories with us in 2010: When I first started teaching in Whitfield, there were almost no Latino children here, maybe 1 % in the late 80’s and that number was growing. It was sort of a natural interest for me because I was teaching some foreign language courses and a little bit of everything and each year I saw more and more kids coming there that were from Mexico and it was interesting to me about the whole process of learning languages, for them. I saw them struggling with no support being taught by indifferent teachers, many doing the best they could, I think. But some of them were actually hostile to them, I believe. But most of them were doing the best they could, I will give them that. None of them had Spanish. None of them had any sort of special skills to teach ESOL.

THE GEORGIA PROJECT

The Georgia Project (GP) was a partnership between two school districts experiencing dramatic changes and a Mexican private university where we were teaching sociology (Schick, 2009).3 It was an agreement between people representing southern communities suddenly altered by immigrant influxes and Mexican scholars interested in supporting Latino American immigrants and their children. It was, since the beginning, a heterodox marriage with very few chances of succeeding, as we will describe in the following sections. We tell the story of this marriage not with the purpose of assessing the achievements and failures of that binational joint venture, but to analyze -as professional, not intrusive, outsiders, with-clear-membership as members of the GP committee-, how the school dilemmas and debates were essential part of the integrating process of international migrant adults and children in Dalton. Again, for us, the schools became the doors opened for observing and analyzing while participating.

How did Georgian educators, civic leaders and school officials take the decision to go to Monterrey, Mexico? This part of the story would be uninteresting if it was a mere anecdote. But it is not the case. It is a central part of the chronicle because behind the visible actors of that partnership, there were other influent participants who explain the course of the events. When “…Georgia institutions including state government and universities failed to respond quickly to Dalton leaders’ impatient requests for assistance…” (Hamann, 1999, p. 9), they looked at the most powerful carpet industrialists in town. Dalton schools officials and civic leaders communicate to the captains of industries how the school transformations were the consequence of the decisions taken by carpet industry -and poultry plants- to hire foreign workers coming from Mexico and Central America. As this causal association between the carpet mills decisions about their workforce and the demographic changes was absolutely visible in a small industrial town, it was easy for school officials and civic leaders to show how industries were part of the “problem” as well as, perhaps, part of the solution.

That kind of interconnection between school districts and industries was not unusual in a mill town like Dalton. In fact, Dalton Public Schools’ creation, in 1886, concurred with the installation Crown Mill, the first important carpet industry in town (Thompson, 1996). Since the beginning of the school history of Dalton, there were number of interrelations between industrial owners and school officials: in 1886, “…the local leaders who were promoting Dalton’s nascent development exploited a loophole in Georgia public education law that permitted cities to establish public school systems using local taxes; they established DPS.” (Hamann, 1999, p. 129).

That sort of interrelation, typical in mill towns with paternalistic traditions (Patton, 1999), explains how the Georgian delegation arrived to the Universidad de Monterrey 110 years after the establishment of DPS. Shaw Industries had a productive joint venture with a branch of the Alfa Corporation in Monterrey, taking advantage of opportunities provided by the North American Free Trade Agreement. Since this commercial and manufacturing linkage, both industrialists of Dalton and Monterrey had frequent contacts and personal ties.

The interest of this story is that it shows the source of the binational interconnection. The GP was, in some sense, an accidental by-product of globalized industries and, also, an indicator of the capacity of big corporations to influence the making decision processes in educational institutions, both in a mill town, as Dalton, and in an industrial city (with long paternalistic traditions; Palacios and Lamanthe, 2010) as Monterrey.

THE DALTON EDUCATORS’ FOUNDATIONS: ASSIMILATION AS UNIDIRECTIONAL PROCESS

Regardless these important and powerful economic global forces, people who intervened in the design and implementation of that unorthodox educational joint venture had played their own roles and followed their own logics of action. Let’s begin with the logic of action and rationale from which the Georgian participants acted. According to Hamann (1999), the school officials and members of the Dalton Board of Education, shared the common beliefs that integration/incorporation of newcomers was a unidirectional process of assimilation based in Darwinists thesis justifying the idea of cultural progress (including certainly the ranking of inferior and superior cultures and societies). In this vein, the Georgian actors considered that the principal task of the schools was to transform newcomers, in a unidirectional way, from foreign people into productive citizens respectful of American and local values: “the structural framework within which the Georgia Project was being enacted can be further linked with the old ideas that immigration was a problem, that assimilation conducted through schooling would lead to its amelioration, and that cultures could be thought of an evolutionary and hierarchical terms.” (Hamann, 1999, p. xxv).

In more practical terms, generally, Georgian participants in the creation of the Georgia Project recognized that their community had changed since economic forces transformed its demography. They acknowledged also that those demographic changes drew several unexpected consequences they could not manage and probably they did not know how to manage. Schools were at the center of these transformations, namely, the arena where the processes of integrating newcomers would occur. Schools were viewed as being the agents of that unidirectional assimilation urgently needed by the dominant segments of the receiving society.

Based in these beliefs and diagnosis, school officials and members of the Board of Education, fully recognized they needed bilingual teachers. They needed to complement their teacher’s body. Meanwhile, they did not imagine or consider any change in the other crucial components of the educational processes like curriculum’s architecture and purposes, or methods implemented in the schools, or contents taught to students, or methodologies of designing tests and evaluations, or special training programs to local, regular and certified teachers, or new forms of pedagogical relationships, or creating new symbols for welcoming newcomers, or imaginative forms of establishing communication with parents and adult members of immigrant society. From the outset, schools were considered agents that had to remain intact in their whole conception, except for one thing: they needed bilingual teachers.

The first team of those bilingual teachers arrived from Monterrey to Dalton in 1997. Their arrival was vastly publicized in the local and most influent newspaper, in local radio stations, public and private meetings. The GP became a small but noisy symbol of some Dalton community members’ will to integrate newcomers and their children through schools. The message sent to the public was: Mexican bilingual teachers arrived in our school system to support teachers and the schooling success of Latino children.

THE INITIAL PROPOSALS OF THE SCHOLARS OF UNIVERSIDAD DE MONTERREY

As scholars based at the Universidad de Monterrey, the logic of action we followed was entirely different from the “needs” of our Georgian partners. We read carefully the first letter sent to us by the Superintendent of DPS in September 27, 1996: “I have now met with our eight school principals on two occasions to discuss the possibilities of assistance from Universidad de Monterrey…We have discussed many strategies which could assist us…All of us agree that adult bilingual assistance in the classes would be of great benefit to all concerned. By providing instruction in the native language, these students could increase their skill levels in academic subjects. Also, we could provide intensive English instruction with the ultimate goal being that of a literate bilingual student…Perhaps this program could lead to an exchange of educators. We could possibly send some of our teachers for training in Mexico. Other ideas include: instructing our teachers in the Spanish language, creating Saturday classes for children and adults (families), summer school, obtaining textbooks in Spanish and many others”. The letter pointed out not a unidirectional way of assimilating process but a two-way welcoming integration strategy for migrant workers and their families. Indeed, we saw, from this letter, school leaders transforming monolingual instruction in the schools.

Our interpretation of the first letter explains why during our first meeting in Monterrey, we proposed three new components of the inter-institutional agreement. As part of the signed accord, we suggested (as it was literally defined in the text of the Accord signed in March 1997):

A “Bilingual Education Curriculum Design Program”.

An “Intensive Spanish and Mexican Culture Program… educators from the two School Systems will spend four weeks of intensive Spanish instruction as well as immersion in cultural activities at the Universidad de Monterrey”.

Additionally, we recommended a “Parent and Industry Workplace Involvement Program: The Universidad de Monterrey will conduct a comprehensive study of the Dalton/Whitfield community to reveal detailed demographic information related to the Latino Community. The information provided by the study will be used to develop and implement the following three programs: The recognition and development of community leaders; adult biliteracy; and parent, school and industry programs”.

Those programs, in fact, were subordinated to the most important segment of the agreement, at least for our Georgian partners: “Universidad de Monterrey Teacher Assistance…students and/or graduates will be assisting educators in the two school systems…”

Hamann (1999), analyzing the components of the GP concluded: “…DPS first approached the Universidad de Monterrey only with the intent of finding bilingual teachers; the other components of the Georgia Project were all suggested by the Universidad de Monterrey” (p. 162).

VALIDATING THE MONTERREY’S SCHOLARS FOREMOST PROPOSALS

Our field notes taken during our several early visits to Dalton in 1997 attest: we found that there were no real/significant interactions between the receiving society and the group of newcomers. Even in the institutional arenas where interactions were feasible (the workplaces and the schools), the contact between both societies was limited to arrangements following subordinated relations (boss-worker, teacher-student). Therefore, both groups remained strangers to each other. Ironically, in June 1997, we wrote in our field notes: “one of the rare social spaces for inter-ethnic real interacting was the dancing night club for Mexicans and other Latinos where we could see white poor young women who seemed to have learned well to dance Mexican music”.

While working with our partners in Dalton, we had intensive, privileged, exhausting but fascinating field experiences. We visited schools, certainly, but also workplaces (several carpet mills), churches, malls, public parks, neighborhoods (for immigrants and for longer-term residents), soccer fields, restaurants (both patronized by Mexicans and by non-Mexicans), stores, hairdresser shops, bars, and just one dancing club. We talked with teachers, principals, school district officials, numerous Latino students, Catholic priests (and other ministers), industrial executives, civic leaders, restaurant owners (both Mexicans and Americans), several Latino business owners and, of course, many Mexican newcomers and members of their families. We concluded that there were no channels of meaningful interaction between immigrants and non-immigrants. Moreover, we discovered that there were no interlocutors (i.e. people who were able to go-between). Nobody could play the role of mediating between newcomers and receiving society members, because none had the expertise of knowing both worlds.

That lack of real interaction was combined with a confusion we identify since our first visits to Dalton. Civic leaders, mill executives, and school official thought -sincerely- that the Catholic priest, an energetic “Anglo” with German origins, was the legitimate interlocutor between them and the Latino community just because he was bilingual. Besides the priest, they thought of the Centro Latino, a kind of private relief organization led by a Baptist reverend from Puerto Rico. There were no interlocutors, even if they seemed to be, simply because they were not recognized at all by the migrants we met. It seemed, in consequence, that our assumptions about the needs of Dalton/Whitfield societies in order to integrate immigrants were presumably right.

The spirit of the three components we described in the former section was to train and empower multiple players able to produce significant two-way interactions. Even the role of bilingual Monterrey teachers, in the context of schools, should be, based on our findings, mediators between the school and children/parents, advocates of children, and mentors of students (explaining the rules, principles, and foundations of the American schools to them).

THE BILINGUAL TEACHERS AID PROGRAM

The Monterrey bilingual assistant teachers (also Georgia Project teachers) program started in 1997 and ended up in 2001 in DPS. That program continued in WCS until 2007 and expanded its services to other school districts of northern Georgia and one school district in South Georgia. All the teachers who participated were Mexican, bilingual, graduates from 4-year BA programs in education, linguistics or pedagogy from the most important universities in Monterrey, and most of them stayed in Georgia schools two or three years; then, they returned to Mexico. They were not integrated as regular teachers but as paraprofessionals because they lacked Georgia State certification. As paraprofessionals, they were first used as translators, and even then, they were not considered as ESL assistant teachers at all. In the schools, after a period of doubt about how to use the bilingual paraprofessionals, most became instructors working with a method of rapid teaching/learning English program known as Direct Instruction, and they did not become bilingual teachers as proposed in the original agreement.

The Mexican teachers became English instructors following an entirely scripted methodology that was presumably successful for acquiring English proficiency in a very short term. The monthly reports sent to us by the Monterrey teachers working in DPS the school years 1997-2000 described their dissatisfaction and distress because they were transformed finally into English teachers for ELL’s students (and, sometimes, for white students with learning disabilities). Their frustration was understandable, not just because they were not English native speakers, but also because of what Hamman (1999) noted: “The line of thinking claimed by Direct Instruction proponents often comes with either veiled or explicit assumptions that teachers’ expectations for students are too low and that too many teachers are not competent enough to be able to deliver an effective curriculum without careful guidance or even complete scripting.” (p. 55).

We selected from our files the most significant suggestions and concerns we discussed with our partners in Georgia. First, we pointed out that the principals did not know or knew very little about the goals of the Georgia Project. Their lack of participation explained why Monterrey teachers did not have clear ideas about their responsibilities and tasks. Hosted in the schools as paraprofessionals, they were merely substitutes of regular teachers in peripheral activities. We concluded from this that the Monterrey teachers had limited membership in the faculty body of DPS. They were not only paraprofessionals, but outsiders, foreigners who would never entirely share the membership of the receiving society.

Second, we found that the only chance Monterrey teachers had to be perceived as useful for DPS faculty was to become effective English instructors. We considered this a contradictory task with the spirit of the GP, given the fact that bilingual teachers from Monterrey were not native English speakers.

Third, we insisted using these teachers to support the most vulnerable migrant children: those who were newcomers in the United States and did not American school rules, habits, codes, and traditions. We proposed to focus on their cultural and social transitions instead of language barriers. For example, in June 2008, we pointed out: Culturally, the “snapping” of fingers (gesture permanently used in Direct Instruction methodology) is sometimes regarded as “disrespectful” by Hispanics. (Note: In Mexico, you snap only at pet dogs when you are asking them to come close to you). That was why we proposed to transform Monterrey teachers from bilingual paraprofessionals into cultural mediators -because presumably they understood the two worlds: the backgrounds of Latin American children and southern schools-. It was an invitation to distinguish diverse categories of the students labeled Hispanics, asking special attention to those who were arriving directly from Mexico or Central America to Dalton.

Fourth, we called attention several times to the fact that the most valuable skill of the teachers from Monterrey was not only that they spoke Spanish (in fact, Mexican Spanish), but also they had some expertise in Mexican schools dynamics, contents, methods of testing, and curriculum. It meant that they were able to culturally communicate better with students coming from Mexico than any other member of the school body in DPS and could play the role of mediators and advocates of newcomers.4

Considering only the valuable linguistic dexterity (they spoke Mexican Spanish), we suggested maximizing that resource as follows: The Monterrey bilingual teachers could help the Anglo teachers learn Spanish, especially basic vocabulary and phrases that would be helpful to them when communicating with Hispanic students and parents (June 1998). The Monterrey teachers may teach advanced Spanish classes for Hispanic students (June 1999). Avoid translation in the classrooms: explanations should not be given in English and then translated to Spanish for the Hispanic students who do not speak English. If this is done, they will never learn English, or will learn it at a much slower rate (June 1998). Improve vocabulary; pay attention not only to words but to concepts (March 1999).

Fifth, once we recognized, in 2000, that the schools would not be transformed themselves pushed by the GP innovative spirit of collaboration, we proposed much more modest arrangements in which the Monterrey bilingual teachers and regular teachers could participate in order to support the children of migrants. We suggested, to work “at the instructor/student interface level with the following micro-initiatives: comprehend and value the backgrounds of Mexicans students, supporting a true instructor/student interface, creating micromanagements of the mainstream curriculum, collaborating with Universidad de Monterrey Summer Institute veterans, doing bicultural accommodations, planning bilingual sessions, inducing Mexican students to seek a school success, and improve self-esteem of Mexican students”. Several Monterrey teachers and even Georgia teachers could implement those micro accommodations for the benefit of newcomer students. Working in an elementary school, one the Mexican paraprofessionals claimed a small part of school space (in fact, a small room) as a symbol of the welcoming gesture of teachers and staff for newcomers. She decorated the place with familiar school symbols for Mexican children, hanged signs in Spanish, and placed in the center of the room the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. She built a sanctuary for Latino students, a space where they could discuss in Spanish about their moments of distress at school, talk about their families, their migratory experiences, evaluate their learning progress, and clarify misunderstandings related to their integration in the school. In that sanctuary we met a child, 8 years old, who was born in Guatemala. That “Hispanic” student, in fact a Mayan boy, spoke very little Spanish. The Monterrey teacher decided to communicate with him in English while trying to learn some words in Maya. Interestingly, the principal of the school, a middle age woman who never had gone to Mexico, born in Dalton, was happy to see what the Monterrey teacher had done.

These kinds of micro-arrangements were implemented successfully in eleven schools (eight in DPS and three in WCS) where the 41 Monterrey teachers (all women) were working during the school years between 1997 to 2002. In the sphere of home/school interactions, they clearly facilitated communication between school administrators, teachers and Latino parents. They became, in every school, the point of reference for immigrant mothers and fathers. They were not just interpreters or translators. Certainly, they played such role when offering translation assistance or sending written messages in Spanish. But, simultaneously, they clearly improved classroom and school/home communication. As Hamman (1998) noted, almost a year after of the beginning of Teacher Aid Program in DPS and WCS: “It is hard to overestimate the apparent positive effects of the presence of Universidad de Monterrey-trained instructors in Dalton’s schools. In particular, I have noticed… The Monterrey instructors are frequently relied upon by teachers and administrators as information sources. As Dalton teachers try to communicate with and effectively educate Mexican immigrant students, they are significantly aided by the chance to ask a Mexican colleague…about how school is organized and conducted in Mexico and what the school experiences of Mexican students or parents may have been”.

Additionally, Monterrey teachers were often able to identify the real academic progress of LEP students -in terms comprehension of concepts, methods, particularly in math and sciences- even if students could not express this appropriately in English. They used to explain to Dalton/Whitfield teachers: “he/she understood”. These kinds of practices kept LEP students from falling behind in particularly important subjects for schools and teachers.

We also recognized, as Hamman (1998) did, that the Monterrey teachers became counselors/confidants of Latino students. Playing this role, they could help children and adolescents overcome difficult family events, harmful migratory experiences, or painful school interactions: “…it has allowed the schools to become more aware of the specific needs and circumstances of individual students (as the Monterrey teachers have served as conduits of information from Latino students to school administrators and teachers)”.

Sixth, frequently Monterrey teachers served as role-models for working-class children. Monterrey teachers showed their students, implicitly and explicitly, that they could become bilingual, biliterate, and successful in school. Particularly those who had worked in Dalton High School motivated their Latino students to be better students, finish high school and aspire to go to a college. As Hamman wrote in his personal communication to the GP committee, in 1998: “Given the recentness of Dalton’s Hispanic influx, and the concentration of Hispanic adults in Dalton in non-professional job categories, it is easy for students and teachers of all ethnic identities to absorb messages linking Hispanic ethnic identity and job prospects which do not require high school completion. By their very presence, the Monterrey instructors serve as counterexamples, challenging such an easy but mistaken belief…Also the Monterrey teachers’ professionalism and professional credentials challenge anyone’s notion that Hispanics cannot or do not become professionals.”

Last but not least, in some cases these teachers impeded the practice of using Latino students’ low proficiency in English as an indicator of low intelligence. One of the Monterrey teachers, specialized in special education -degree earned in Mexico- who spent more than five years serving the schools of WCS, summarized her contribution to the schools as follows: “my most important contribution as teacher there [WPS schools] was that I could professionally verify, in Spanish, the quality and objectivity of test’s results my American colleagues used to apply for classifying kids… often I could change incorrect decisions they were taken with boys and girls” (Monterrey teacher, personal written communication, February 2010).

NEWCOMERS IN SCHOOLS: THE FRAGMENTATION OF THE HOST SOCIETY

At the time, we started visiting Dalton and Whitfield, J. G. Keyes (1999) conducted a survey among 264 teachers of six elementary schools of DPS (out of 327 total full and part time elementary school teachers). The main goal of his work was to measure the DPS “educators’ attitudes” toward the school district’s bilingual education plans and the presence of bilingual Monterrey teachers who first arrived during the 1997-98 academic year. The data he collected from a standardized questionnaire give us an insight into the fragmentation of local teachers’ views about the arrival of children of immigrants and migrant children and the expected role of the schools in welcoming or unwelcoming them.

According to the Keyes’s survey, about one out of three DPS elementary school teachers clearly judged that bilingual education programs, multicultural perspectives, inclusion of diversity, were not the ways the school district had to adopt in order to integrate newcomers. Furthermore, 27 percent of respondents considered that bilingual education programs do not support ELL students; from their view, it delays non-English speaker students “from entering into the mainstream of life in the United States” (p. 162); also, 42 percent of the teachers did not agree with the program of hiring bilingual teachers from Mexico.

On the other side of the spectrum, almost half (49 percent) of teachers who responded the questionnaire acknowledged their society was becoming bilingual (“English and Spanish are essential in this part of the United States”). It seems like often the teachers would recognize the facts and separate them from their wishes. Ideally, school curricula, organization, materials must to remain unchanged. However, the drastic changes in the school district enrollment, by the end of the 90s, already announced the irreversible trends the schools had to contend with. It seemed also that some teachers disagreed with the implementation of two-way bilingual education strategies in his/her school while admitting that his/her community was becoming bilingual.

The survey did not allow to explore in details the reasons for the teachers’ resistance to the inclusion of languages other than English in the schools. However, some short written explanations were documented by Keyes (1999). One teacher wrote: “I feel that people who come to this country should be able to speak English. If I went to another country to live, I would learn their language and not expect them to learn mine” (p. 150). A second one explained with much more accuracy, relating multiculturalism with potential violence: “I believe in helping our Hispanics assimilate into American culture. By providing so much bilingual education and bilingual social services, we are no longer helping them assimilate we are helping them to segregate”. “If I moved to Mexico, I would expect to have to learn Spanish. If you would like to see multiculturalism at its best, then look at Bosnia. They are so focused on their differences that they cannot see anything in common, and they are killing each other as a consequence” (p. 151).

These two assimilationist teachers expressed their commitment in “integrating” the children newcomers, one of the name of nationalistic norms (one nation, one language), the other in the name of peace (no one wants to see Bosnia in the U.S. South). Their positions were far from those of the so called Citizens Against Illegal Aliens’ positions (a local organization advocating for deportation and depicting dark stories about Latino population).

In addition to teachers resisting changes in schools, we found several teachers who welcomed the backgrounds and languages of their new students. They saw this transformation as an opportunity to learn and/or improve their Spanish language skills in order to better serve their Latino students. Some others asked students to speak Spanish in class and asked these pupils teach them the language. There were even two teachers we met who invited their Latino students to speak in Spanish just to challenge their Anglo monolingual students; clearly, those teachers thought they would elicit respect and admiration for their Latino kids among their monolingual peers, making apparent that newcomers are capable of speaking in two languages.

As it is evident, teachers were divided in terms of how to educationally welcome newcomers and how to better integrate Spanish-speaking children in their schools; and more important, DPS teachers had divergent definitions about how to better integrate them. To be clear, they were divided but not opposed to serving these students. Instead, because of practical, moral, legal, religious or multiculturalist reasons, they expressed differentiated and nuanced stances about what to do in order to respond to the school demographic, cultural and linguistic changes.

Furthermore, the teachers’ positions about their Latino students were changing. Cherryl, an ESL southern DPS elementary school teacher, born in Alabama, described her own itinerary as follows: “I guess… it is unusual that I teach ESOL considering the area that I grew up in. I grew up in a small rural town in Northeast Alabama. It was a town made up of all white people. There were lots of prejudices against blacks. My first teaching job was in a majority black school. People back home could not believe that I was teaching in a black school. My last teaching experience in Alabama was at a small rural town in the valley between Sand Mountain and Lookout Mountain. This prejudiced community contained whites, blacks, and a large Hispanic culture. Teaching [there] is how I was introduced to ESL. I feel that I’ve always tried to look at the people and not the color of their skin. I had not been around many blacks until I went to college. I was not around Hispanics until I went to Collinsville” (Dalton ESOL teacher’s dairy written in 2000).

Julia, the teacher we quoted above and who stated: “When the influx began, it was really bad. I didn’t want to work here” (Dalton Public Schools) described her personal story (we interviewed her 13 years after the beginning of the GP, in February 2010): It was like that for me growing up. When I was raised up to not be prejudiced. Though my parents [born in 1945] taught me one way, they still could not get past the social stigma cause this was the early 70s when integration hit south Georgia, so it was a real hot social issue. They certainly encouraged me to have any friends I wanted and many of my friends were black, but still they never could…it really bothered my mother, and I could tell why she didn’t want to say the real reason why when I would ask if one of my black friends could spend the night over…They raised me not to be racists and they’re not, but go to that generation and they still couldn’t get past that stigma. Now of course in my generation, I had no problem with that. It matters not one bit which child comes to my house if they are a friend of my child…but it took a generation to…shake the way they were raised. I think that’s just what’s going on now with whites and Hispanics. It’s just 25 years later…That’s why I think there was a lot of cultural awareness… -my training had been at XXX University-. So if you think Dalton is backwards, you go up to XXX Kentucky and…there was nothing. My professors, I had one from Columbia [University], so he had no clue what Mexico was like [she did a minor in Spanish]. He’d never been there. And the rest were Americans who learned how to speak Spanish…A lot of my preconceptions of what a Mexican student was were stereotypical so I worked only 6 months in the schools before I did the Georgia Project so I had a lot of cultural eye openings. Realizing that, ok when a parent comes late to a parent conference they’re not being rude, this is what is acceptable for their culture….there are a lot of ways that I learned to accept my students and my families better…a lot of us who did the Georgia Project were able to come back to our grade levels and our schools and say ‘ok, this is the culture that were working with’ and I think that slowly the cultures have merged [fused] in Dalton. I think there’s a long way to go, but I think it’s the kids is where it’s starting…I know from my 13 years teaching that’s what has been the most exciting to see, was that it’s starting in the schools with the kids. (Interview, February 2010; underlying by authors).

What Julia pointed out is that integration processes have to be comprehended as intergenerational transformations, as a long and non-linear process. She cautioned us not to draw conclusions from snapshots during the process. She was aware of this, like other of our informants, as it was Susan (born in Dalton in the 40s), one of our first white Daltonian informants whose vision about the Latino influx we mentioned above. Given her long experience in the local government, Susan has a sense of history. She portrayed the process of integration as the realm of multiple doubts, encounters and transitions taking place in her own society through 2000. She witnessed how hard it was for Dalton schools to integrate African Americans during the last 60 years, even if the city had no more than 5 percent of its population classified as blacks. As we attested elsewhere, African Americans were almost invisible for the white community members (Hernández-León and Zúñiga, 2005). When black children first enrolled in integrated Dalton schools (during 60s and 70s), -Susan described- very few teachers knew what to do with them. Drawing a parallel with the integration of African Americans, she argued that (at the beginning of the XXI century) the education and integration of Latino students presented Dalton with a similar challenge. According to her, the receiving community was not ready to face the challenges involved in the sudden arrival of Latinos. The carpet industry brought the migrant workforce it needed, but when migration started, people had no idea of what to do (interview in March 2000); she remarked: the community was not expecting such a fast transformation, and social local organizations were not ready to respond to it. In her account, she told to us that it was not until 1996 when we recognized we had problems with teachers at the schools (in terms of being able and capable to teach non-English speaking immigrant students).

In a largely monolingual English-speaking, deeply religious society, such as Dalton, with a limited experience dealing with cultural diversity, we also encountered Ted, who was born and raised in Dalton. He is (was) a very religious man who recognized the changes he could develop in his K-2 school and the responsibility of professional educators to support micro and meso accommodations to welcome Latino students: I think I was the most fortunate of all y’all [he is talking to other teachers we invited and gathered in a restaurant of Dalton to discuss the evolution of schools; February 2010] because Mrs. XXX [the principal], XXX [the assistant principal], and XXX [the second assistant principal] thru XXX [the superintendent], they really took it on. They took the Georgia Project seriously. We had 4 of the first teachers come and I actually was teaching a reading program then, a Reading Recovery, in which I trained those teachers to do this. Saw them using English and Spanish, the Monterrey teachers, to teach these children how to read and began to foster wanting to learn the Spanish more to that I could relate vocabulary and reading…‘this word means this’ ‘oh, now I can take this book and go with it’. But everything started coming into place. We started getting 2 Spanish teachers. We had 4 elementary Mexican teachers there. They hired office staff. I think XXX [name of the school] was the first to hire office staff. They saw the importance of the first person who you see when you walk into the door for a parent to feel like this is a hospitable is to have someone say hello in Spanish. Luckily, XXX school has always supplied that front office, bilingual staff. For myself, I have actually taken Spanish and actually improved and I really use it daily. I have more fun having parent conference totally in Spanish now and I think the parents appreciate it (Interview 2010; underlying by authors). Ted started learning Spanish when the GP was implemented in 1997. He spent two summers in Monterrey, then one in Oaxaca, and one more in Cuernavaca.

CONCLUSIONS

Acting as participant observers and using the schools as observatories of a complex and abrupt process of integration, we discovered the ongoing web that multiple and heterogeneous actors were weaving during more than two decades of doubts, fears, trials, surprises, and achievements.

The Georgia Project served as a device that invited those involved in weaving this web -in the schools and out of the schools- to imagine, define, and act in the processes of welcoming the newest members of this southern, industrial society. Every player, like all social players, acted his/her role in constrained conditions.

School authorities recognized they were (are) facing changes they did not provoke; they suffered the consequences of decisions taken by powerful business owners in town. Their most visible challenge, then, was children talking and understanding languages other than English. They sought help from state institutions and did not find a positive and useful response. Encouraged by civic leaders, particularly an influential attorney and former congressman, school officials ventured in collaboration with a Mexican university, searched and received the funding, and advertised the heterodox project with unique traits: “The Georgia Project was not a model created somewhere else and imported to Dalton, nor was it a model that arose out of a vacuum or from the singular benevolence of community leaders. The Georgia Project was an organic Dalton/Universidad de Monterrey creation, put together in the face of rapidly changing demographics.” (Hamann, 1999, p. 181).

Schools were right in the middle of a multifaceted social transformation induced by immigration. These central institutions used important community resources to meet a new challenge and outline the future of the community. In a national context with an increasingly visible English-only movement, the social actors of Dalton and Whitfield School were (are) creative and purposeful, including those who defended the continuity of their history and local traditions.

The diverse players we encountered during these years apparently were not unmovable in their original positions. Migrants and native experienced fundamental transformations and discovered new ways to define their ever changing situations and act accordingly. Some of them acknowledge that the processes of immigration, diversity and of building new sense of community were hard, long and risky.

Certainly, immigrants were in the most subordinate position, politically and socially. They knew they had to pay their share of humiliation and segregation. However, most of them were parents of children attending the schools, workers in the local mills and taxpayers, enjoying a limited membership, which in turn gave them a chance participate in the weaving of a small part of the web.

In light of the empirical evidence and analysis of the experiences of DPS and WCS welcoming children of immigrants and migrants children, it is basically impossible to sustain the dichotomous explanation used by scholars used to explaining the integration of immigrants to host societies. This dichotomous explanation contends that host societies in industrial countries are divided into two categories: those who adhere to pro-immigrant scripts and those who hold anti-immigrant scripts (Suárez-Orozco 1998). We have argued here that in matters of schooling and education, in Dalton and Whitfield, the process of the integration was much more nuanced and complex, fragmented and contradictory.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)