Introduction

The family Polynoidae Kinberg, 1856 is one of the largest groups of marine annelids, and although there is some discrepancy about the generic definition for several taxa, and many synonyms were introduced without revisions, or after using a rather wide definition for genera, Polynoidae includes 12-13% of all polychaete genera, and about 8% or all polychaete species. Thus, Polynoidae would include almost 180 genera and about 900 species in some sources (Pamungkas et al., 2019), or 167 genera and 870 species (Read & Fauchald, 1924), but the most relevant feature is that the number of new taxa proposed per year is still growing (Pamungkas et al., 2019). One problem in identifying marine scaleworms is that they often break in parts, detach their elytra, or both, and this is widespread in specimens from the intertidal to abyssal depths. For this reason, many species have been described based on incomplete specimens. Further, as indicated by Barnich and Fiege (2009), as a result of a low number of taxonomic publications or revisions, for many polynoid genera “neither the respective generic nor specific identification characters have been critically evaluated.” This is further complicated because about 30% of all polynoid species are only known after the original description (Hourdez, 2024 pers. comm.).

The polynoin genera LagiscaMalmgren, 1865 and EunoeMalmgren, 1865 are very similar by having 15 pairs of elytra but final segments without elytra, notochaetae as thick as, or thicker than neurochaetae, never with pilose or capillary tips, neurochaetae without semilunar pockets, with tips uni- or bidentate, ventral cirri digitate, venter smooth (Fauchald, 1977). The main difference separating them is the type of neurochaetae; in Lagisca there are at least some bidentate ones, whereas in Eunoe all are unidentate. Pettibone (1963) regarded both, Eunoe and Lagisca as subgenera of HarmothoeKinberg, 1856. Malmgren (1865: key) separated Lagisca from Harmothoe because of the extent of dorsal cover by elytra. In Lagisca, the last segments are exposed, whereas in Harmothoe they are always covered. These 2 genera are regarded as synonyms because besides both having bidentate neurochaetae, larger specimens of Harmothoe usually have the last segments exposed (Barnich et al., 2006). However, as indicated by Fauvel (1916), the diagnostic relevance of this feature implies there are 12-19 chaetigers uncovered, as in HermadionKinberg, 1856, against a few (up to 5) in Harmothoe and other genera.

On the other hand, Eunoe also resembles HermadionKinberg, 1856, another subgenus in Harmothoe after Pettibone (1963), which is regarded as distinct by Wehe (2006). They are similar to each other by having the same number of elytra, final segments without elytra, and notochaetae as thick as, or thicker than neurochaetae. The main differences between them are that Eunoe species have less segments (40 vs. 50 or more), and neurochaetae are all unidentate in Eunoe, whereas they were regarded as uni- or bidentate in Hermadion. However, Bock et al. (2010) revised Hermadion, redefined the genus, and concluded it is monotypic, with H. magalhaensi Kinberg, 1856, as its type species. They did not provide an emended diagnosis but after their key, the diagnostic features would include body short, with up to 50 segments, prostomium without cephalic peaks, anterior eyes towards anterior margin (after figure), notochaetae with blunt tips, and neurochaetae denticulate, without semilunar pockets.

Hartman (1938) studied the holotype of Lagisca crassa and although she hesitated about its placement in EunoeMalmgren, 1865, she completed the original description, corrected some details and included illustrations for the prostomium, 1 parapodium, and tips of 1 notochaeta and 2 neurochaetae. The prostomium has the anterior eyes ventral, under anterior prostomial margin, and chaetae were depicted with better definition of their fine details; she also indicated that palps, antennae and dorsal cirri were smooth, and that aciculae are exposed. Later, Hartman (1956, 1959) listed Treadwell’s species in Eunoe and hence confirmed the new combination.

Rozbaczylo (1985) noted that 3 species of Eunoe had been recorded for Chile: E. crassa (Treadwell, 1924), E. opalinaM’Intosh, 1885, and E. rhizoicolaHartmann-Schröder, 1962. However, regarding E. crassa, after the original description, the species has been listed for Chile by Wesenberg-Lund (1962) but no additional specimens have been found.

On the other hand, Hermadion magalhaensi has more records for Chile, but only the original description (and the one for its junior synonym H. longicirratusKinberg, 1856, plus 2 figures by Fauvel [1916]) has been illustrated, with all other records only listing the species in several Chilean localities from the intertidal to 200 m water depth (Rozbaczylo, 1985).

In this contribution, we document the discovery of some specimens of Eunoe crassa (Treadwell, 1924), collected in the type locality, and deposited in the University of Miami Voss Museum of Marine Invertebrates collection. Because the specimens are well-preserved, some remarks are introduced in the diagnosis of the involved genera, and the diagnostic features are clarified, explained, and accompanied by some illustrations. We also conclude, after the study of the holotype of E. crassa, that it is a junior synonym of H. magalhaensi.

Materials and methods

During part of the cruise 23 of the USNS Eltanin, some specimens were collected in Punta Arenas, Chile. They were deposited in the University of Miami Voss Museum of Marine Invertebrates (UMML). Additional specimens for comparison of H. magalhaensi (USNM 57798) and the holotype of L. crassaTreadwell, 1924 (USNM 19101) were examined at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

Specimens were observed with stereomicroscopes. Some detached elytra, parapodia and chaetae were observed in compound microscopes. Digital photos were stacked with HeliconFocus8, and plates were prepared with PaintShopPro and Photoshop CS.

Results

Order Phyllodocida Dales, 1962

Suborder Aphroditiformia Levinsen, 1883

Family Polynoidae Kinberg, 1856

Subfamily Polynoinae Kinberg, 1856

EunoeMalmgren, 1865

EunoeMalmgren, 1865: 61 (key, diagn.); Fauvel, 1923:50; Uschakov, 1955: 147; Uschakov, 1965: 127 (diagn., key); Fauchald, 1977: 65; Barnich & Fiege, 2003: 29; Wehe. 2006: 125; Barnich & Fiege, 2010: 4. Harmothoe (Eunoe): Pettibone, 1963: 34.

Type species. Polynoe nodosaSars, 1861, by subsequent designation (Uschakov, 1955: 147; Uschakov, 1965: 128; Pettibone, 1963: 34; Jirkov, 2001: 145).

Diagnosis (slightly modified after Barnich and Fiege [2010]). Body depressed, short, with up to 50 segments; dorsum more or less covered by elytra or short posterior region uncovered. Fifteen pairs of elytra on segments 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 26, 29, and 32. Prostomium with or without distinct cephalic peaks and 3 antennae; lateral antennae inserted ventrally to median antenna. Anterior pair of eyes dorsolateral at widest part of prostomium, posterior pair dorsal near hind margin. Parapodia with elongate acicular lobes with both aciculae with tips exposed; neuropodia with a supra-acicular process. Notochaetae stout with distinct rows of spines, tips blunt. Neurochaetae more numerous and thinner, with distinct rows of spines distally and exclusively unidentate tips.

Remarks

EunoeMalmgren, 1865 includes 46 species-group names distributed along all oceans from the intertidal to abyssal depths (Read & Fauchald, 2024). Malmgren (1865) included a key to genera and the diagnostic features for Eunoe were 15 pairs of elytra, covering dorsum, less than 45 segments; lateral antennae subventral; notochaetae with transverse rows of spines; neurochaetae unidentate with tips falcate, thinner than notochaetae. The same features were completed for the diagnosis (Malmgren, 1865).

There are no keys for identifying all Eunoe species. Species have been sorted out after the position of the anterior eyes (under anterior margin vs. median prostomial area), palp surface (papillose vs. spinulose), elytral features (pigmentation, fimbriae, macrotubercles), tips of notochaetae (tapered, mucronate, elongate), tips of neurochaetae (acute, swollen), and size or extent of subdistal denticulate region (short or long). Jimi et al. (2021) described a dimorphic species, and noted that after some molecular indicators, 2 groups of species can be recognized in Eunoe.

Malmgren (1865) included 2 species in Eunoe: E. oerstedi (Fig. 3A-D, in his plate 8), a replacement name for Lepidonote (sic) scabraÖrsted, 1843, and the new combination of E. nodosa (Sars, 1861) for Polynoe nodosaSars, 1861 (Fig. 4A-D in his plate 8). The main difference between these 2 species is the type of macrotubercles because in E. nodosa they have granulose tips, whereas they are spiny in E. oerstedi. On the other hand, the replacement name, E. oerstedi was unnecessary because there was no homonymy (ICZN, 1999, Art. 52.2) or matching combinations, but it has become accepted in recent publications and redescriptions (Barnich & Fiege, 2010; Pettibone, 1954, 1963).

The generic diagnosis included above indicates that prostomium has or lacks cephalic peaks. The type species, E. nodosa (Sars, 1861) has cephalic peaks “rather inconspicuous” (Barnich & Fiege, 2010).

On the other hand, the above diagnosis, slightly modified after Barnich and Fiege (2010), leaves out the species with eyes present towards the anterior prostomial region, as in E. crassa (Treadwell, 1924), not along the widest prostomial area. Other species having anterior eyes displaced anteriorly include E. alvinellaPettibone, 1989; E. barbataMoore, 1910; E. clarkiPettibone, 1951; E. hubrechti (McIntosh, 1900); E. papillosaAmaral & Nonato, 1982; E. rhizoicolaHartmann-Schröder, 1962; E. senta (Moore, 1902); E. spinosaImajima, 1997 and E. subtruncataAnnenkova, 1937. Further, the only species having anterior eyes displaced anteriorly and directed ventrally are E. barbata, E. clarki, E. rhizoicola, E. senta, and E. spinicirris. Another alternative, which should be based upon the study of type materials, would be to transfer these species to Hermadion, but this is beyond our current objectives.

The study of the type material of Lagisca crassaTreadwell, 1924 allowed us to conclude it belongs in Hermadion, and that it is a junior synonym of H. magalhaensiKinberg, 1856, as redescribed elsewhere (Bock et al., 2010).

HermadionKinberg, 1856

HermadionKinberg, 1856: 386; Kinberg, 1858: 22; Baird, 1865: 196; Fauchald, 1977: 62, Bock et al., 2010: 46.

Type species. Hermadion magalhaensiKinberg, 1856 by subsequent designation (Hartman, 1959: 79).

Diagnosis. Body depressed, short, with up to 50 segments, posterior region without elytra. Fifteen pairs of elytra on segments 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 26, 29, and 32. Prostomium without cephalic peaks, and 3 antennae, lateral antennae inserted ventrally to median one. Anterior pair of eyes ventrolateral, posterior pair towards hind margin. Parapodia with elongate acicular lobes with acicular tips exposed; neuropodia without supracicular process. Notochaetae stout with distinct rows of spines, tips blunt. Neurochaetae thinner, with distinct rows of spines distally and only unidentate tips.

Remarks

HermadionKinberg, 1856 is currently regarded as a monotypic genus (Bock et al., 2010). If the species listed above become regarded as members of Hermadion, then the potential diagnostic features would be centered in papillation of dorsal cirri and elytral ornamentation (fimbriae, and macro- and microtubercles); however, as indicated above, revising these species is beyond our current objectives.

Hermadion magalhaensiKinberg, 1856 Figs. 1-4

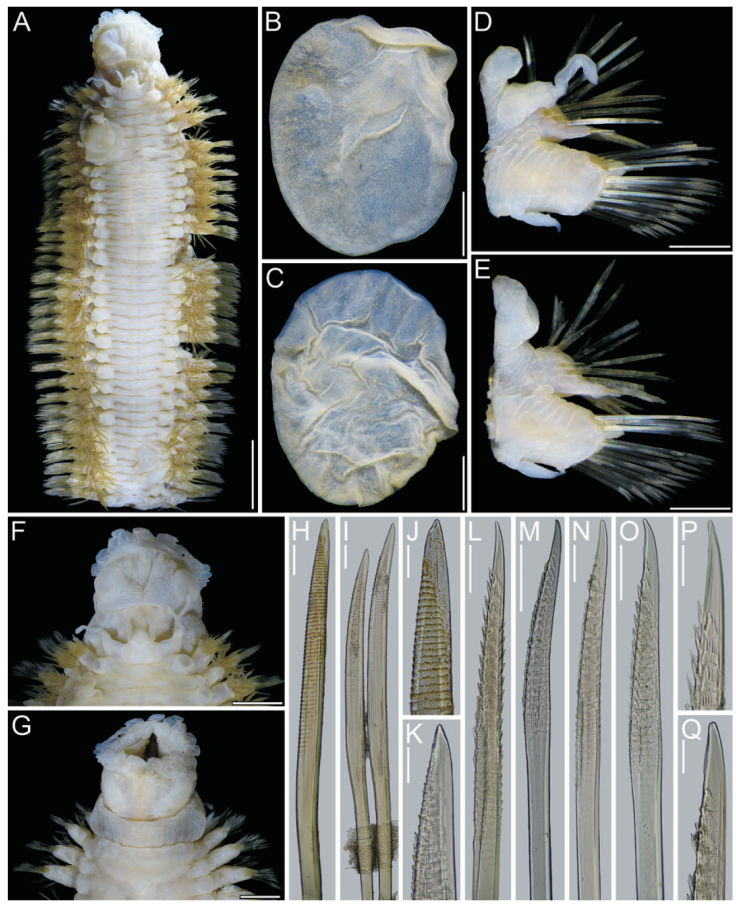

Figure 1 Hermadion magalhaensiKinberg, 1856. Holotype of Lagisca crassaTreadwell, 1924 (USNM 19101). A, Whole specimen, dorsal view; B, C, elytra from anterior segments, seen from above; D, right cirrigerous chaetiger from middle segment, posterior view; E, right elytrigerous segment from middle segment, anterior view; F, anterior end, dorsal view; G, same, ventral view; H, I, notochaetae from middle segment; J, K, tips of same; L, M, supra-acicular neurochaetae from middle segment; N, O, sub-acicular neurochaetae from middle segment; P, tip of supra-acicular neurochaeta; Q, tip of sub-acicular neurochaeta. Scale bars: A, 5 mm; B-E, 1 mm; F, G, 2 mm; H, I, L-O, 0.1 mm; J, K, P, Q, 50 μm.

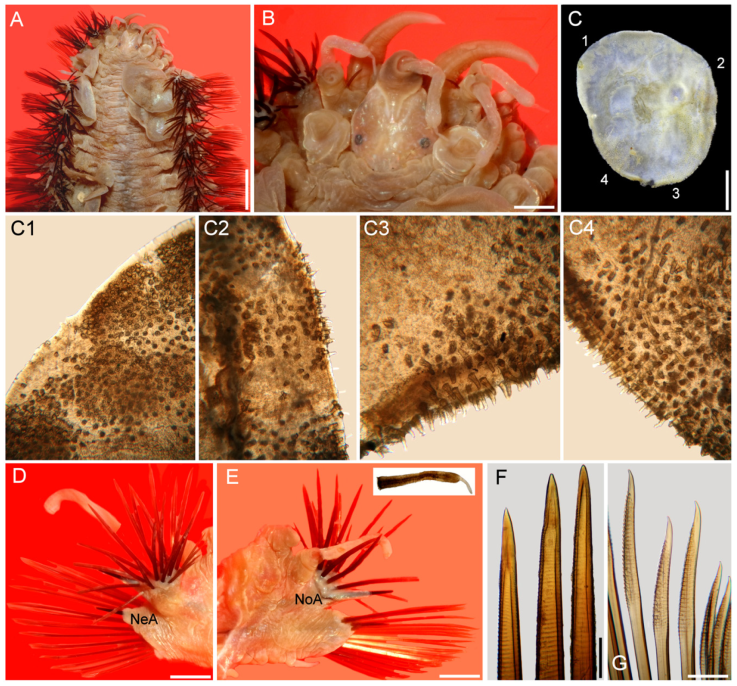

Figure 2 Hermadion magalhaensiKinberg, 1856, topotype specimen (UMML). A, Anterior región, dorsal view; B, anterior end, dorsal view; C, right elytron 6, seen from above (1- 4: sections enlarged in C1-C4); D, chaetiger 18, right parapodium, anterior view (NeA, neuracicular lobe); E, same, posterior view (inset: dorsal cirrus; NoA, notacicular lobe); F, tips of notochaetae; G, tips of neurochaetae. Scale bars: A, 2.1 mm; B, 0.6 mm; C, 1.1 mm; D, E, 1 mm; F, G, 180 µm.

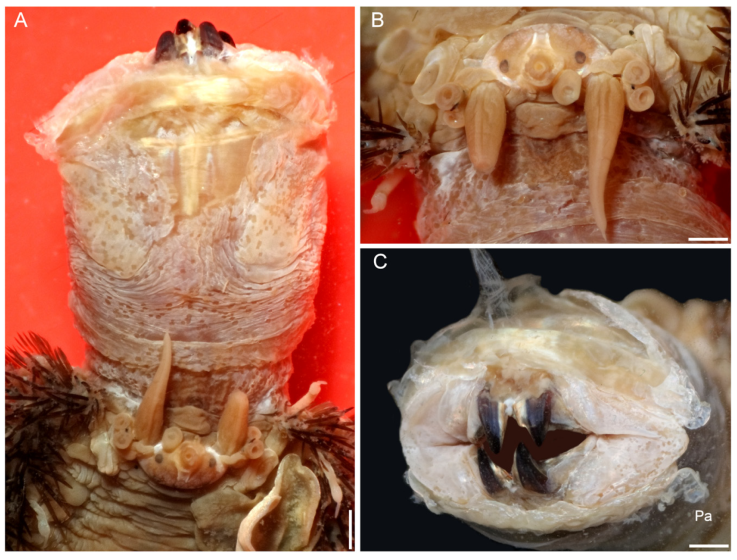

Figure 3 Hermadion magalhaensiKinberg, 1856, topotype specimen (UMML). A, Anterior región and pharynx, dorsal view; B, anterior end, frontal view; C, pharynx opening, frontal view (Pa, papilla). Scale bars: A, 1 mm; B, 0.6 mm; C, 0.9 mm.

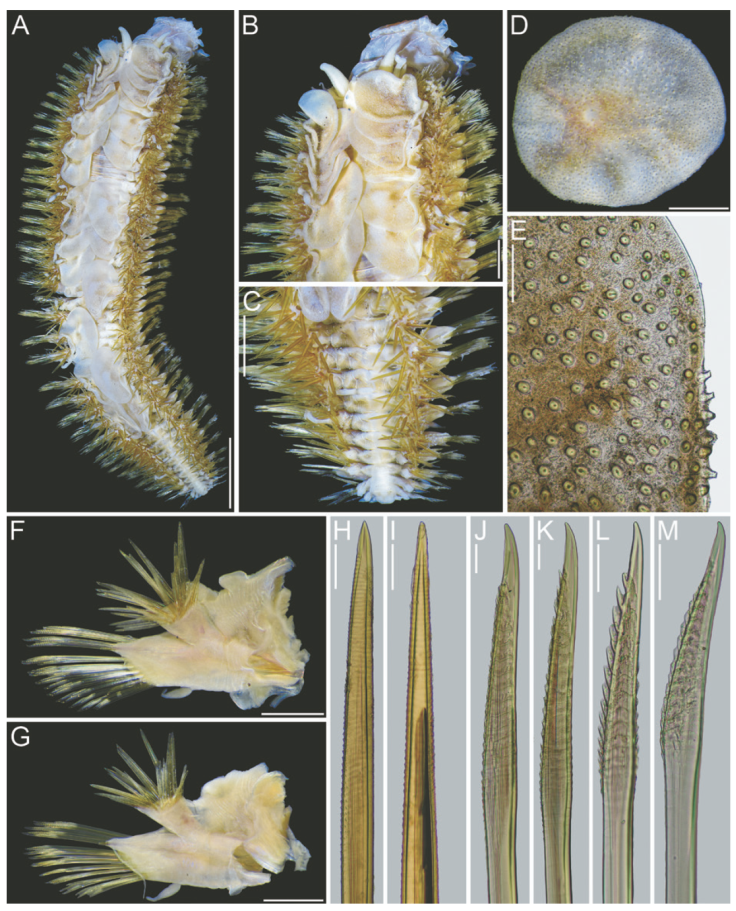

Figure 4 Hermadion magalhaensiKinberg, 1856, topotype specimen (USNM 57798). A, Whole specimen, dorsal view; B, anterior end, dorsal view; C, posterior end, dorsal view; D, right elytron from middle segment, seen from above; E, microtubercles from elytral margin; F, right cirrigerous chaetiger from middle segment, anterior view; G, right elytrigerous chaetiger from middle segment, anterior view; H, I, tips of notochaetae from middle segment; J, K, tips of supra-acicular neurochaetae from middle segment; L, M, tips of sub-acicular neurochaetae from middle segment. Scale bars: A, 3 mm; B, C, 1 mm; D, F, G, 0.5 mm; E, 0.1 mm; H-M, 50 μm.

Hermadion magalhaensiKinberg, 1856: 386; Kinberg, 1858: 22, Pl. 6, Fig. 32; Ehlers, 1897: 15-16; Gravier, 1911: 86-87; Fauvel, 1916: 423-426, Pl. 8, Figs 10, 11; Augener, 1932: 13-14; Hartman, 1964: 35-37 (diagn., syn.); Averintsev, 1972: 123; Bock et al., 2010: 50-53 (redescr., syn.).

Lagisca crassaTreadwell, 1924: 1-3, 4 figs; Wesenberg-Lund, 1962: 26 (list).

Eunoe (?) crassa: Hartman, 1938: 119-120, Fig. 38b-e.

Eunoe crassa: Hartman, 1956: 261, 265 (list); Hartman, 1959: 67 (list).

Diagnosis. Hermadion with elytra without fimbriae, surface covered by short microtubercles, round and elongate spine-like; dorsal cirri with small papillae, tips mucronate, smooth.

Taxonomic summary

Type material. Punta Arenas, Chile. Holotype of Lagisca crassaTreadwell, 1924 (USNM 19101), Punta Arenas, Chile, 1923, F.F. Felippone, coll. (depth unknown).

Additional material. Punta Arenas, Chile. Four specimens (UMML), USNS Eltanin, Cruise 23, Sta. P4-3 (53°11’ S, 70°50’ W), shore collection, by hand, 0.8-1.6 km south of commercial pier, 30 Mar. 1966, fixed in isopropyl alcohol, McSween, coll. 11 specimens (USNM 57798), Cobble Beach, Magellanes, 6 May 1965, J. Mohr, coll.

Holotype of Lagisca crassa. The holotype (USNM 19101) is posteriorly incomplete, 7.3 mm long, 2.4 mm wide, 32 segments (Fig. 1A, C). Most elytra, cephalic appendages and dorsal cirri detached, some parapodia previously dissected, pharynx everted.

Prostomium longer than wide (Fig. 4F); eyes almost faded out, anterior eyes anteroventral (Fig. 1F). Ceratophore of median antenna with a V-shaped depression; ceratostyle missing. Lateral antenna ventral, ceratophores about half as wide as median one; ceratostyles 1.5x longer than ceratophores (Fig. 1F). Palps lost.

Tentacular cirri with chaetae; cirrostyles distally incomplete, slightly longer than cirrophores (Fig. 1F). Facial tubercle not visible dorsally.

Pharynx fully exposed (Fig. 1F, G); no pigments observed, slightly expanded distally; 9 pairs of marginal papillae. Jaws dark brown (Fig. 1G), blunt tips, without accessory denticles.

Elytra pale, non-fimbriate (Fig. 1B, C), with eccentric insertions. Surface almost fully covered with microtubercles; microtubercles rounded, rod-like, or distally truncate.

Parapodia biramous from segment 2. Few dorsal cirri remain attached, all without tips (Fig. 1D). Both notacicular and neuracicular lobes projected, tips of aciculae exposed (Fig. 1D, E). Ventral cirri tapered, reaching base of neuracicular lobe (Fig. 1D, E). Nephridial lobes blunt, present from segment 9 throughout body.

Notochaetae light brown, of different sizes (Fig. 1H, I), each blunt, with series of denticles, margin finely spinulose, tips delicately bent, entire (Fig. 1J, K). Neurochaetae light brown to transparent, subdistally expanded (Fig. 1L-O), with rows of denticles leaving tip smooth (Fig. 1P, Q); tip falcate, unidentate (Fig. 1P, Q).

Posterior end lost (Fig. 1A).

Additional material. The UMML and some USNM specimens were complete, body wall brittle, most elytra detached, some cephalic appendages and dorsal cirri lost, some with some portions removed likely after predatory attacks, especially along anterior region including right parapodia (Fig. 2), or right lateral antenna (Fig. 3B). Some specimens bent laterally, others bent ventrally, 2 with pharynx exposed. Body 35-47 mm long, 9-17 mm wide, 43-47 segments. Elytra overlapping laterally leaving middorsal area exposed in some specimens (Fig. 2A), fully covering it in others (Fig. 4A, B).

Prostomium longer than wide. Eyes black, anterior eyes ventrolateral, not visible dorsally (Fig. 2B), better perceived in frontal view (Fig. 3A, B). Antennae and cirri cylindrical, tips mucronate, blunt. Median antenna with ceratophore forming a V-shaped depression, about 4 times wider than ceratostyle, ceratostyle about as long as prostomium. Lateral antennae ventral, ceratophores about half as wide as median one; ceratostyles lost. Palps thick, short, about as long as median antennae, finely papillate, but papillae not arranged in rows.

Tentacular cirri with cirrophores fused, with chaetae exposed; cirrostyles cylindrical mucronate. Facial tubercle pale, not visible dorsally, better defined after pharynx is exposed.

Elytra barely pigmented, non-fimbriate (Figs 2C, 4D), with variable amount of sediment particles. Surface covered by abundant microtubercles (Fig. 4D), small globular along anterior regions (Fig. 3C1, 2), progressively longer along posterior region, projected beyond elytral margin (Figs. 3C3, 4; 4E). Other specimens with a diffuse spot surrounding central area. Insertion area eccentric, displaced anteriorly and laterally, to the right in right elytra, to the left in left ones.

Parapodia biramous from segment 2. Dorsal cirri finely papillate, papillae not arranged in rows, tip smooth. Notopodia with dorsal cirri cylindrical, tip mucronate (Fig. 2D, E). Notacicular lobe projected, aciculae exposed (Fig. 4F, G). Neuropodia with neuropodial lobe projected, rarely with a long prechaetal subacicular lobe (Fig. 4G). Neuracicular lobe projected, aciculae exposed (Fig. 4F, G). Ventral cirri tapered, short, reaching base of neuracicular lobe. Nephridial lobes blunt, short, present from chaetiger 8-9, continued along body.

Notochaetae dark brown, abundant, roughly verticillate, each blunt, with series of denticles, margin finely spinulose, tips delicately bent, entire (Figs. 2F; 4H, I). Neurochaetae brownish, subdistally expanded, with rows of denticles leaving tip smooth; tip falcate, unidentate (Figs. 2G; 4J-M).

The pharynx is fully exposed; it is 9 mm long in a 46 mm long specimen (Fig. 3A). The outer surface looks maculate but the spots correspond with adsorbed crystals on the surface. The pharynx tube is slightly expanded distally, its margins are eroded and only the lateral papillae are left after erosion of most marginal integument (Fig. 3C); it was described with 9 pairs of marginal papillae. Jaws dark brown, tips blunt, without accessory denticles (Fig. 3C).

Posterior end tapered (Fig. 4C); pygidium with anus terminal; anal cirri short, resembling dorsal cirri.

Remarks

Hermadion magalhaensiKinberg, 1856 and H. longicirratusKinberg, 1856 were both described from the same locality and depth in Saint York Bay, Magellan Strait. The main differences between these species were that H. magalhaensi has smooth elytra, and smooth notochaetae, whereas H. longicirratus has elytra minutely tuberculate and spiny notochaetae; the former species was based on a 52 mm long specimen, whereas the latter on a 14 mm long specimen. The size difference might explain some features present in the smaller specimen and lost after abrasion in the larger specimen. However, the microtubercles in elytra might accumulate sediment and look smooth if they are not carefully cleaned. Fauvel (1916: 425) studied several specimens of different size and concluded H. magalhaensi and H. longicirratus were the same species.

Treadwell (1924) described Lagisca crassa from Punta Arenas, Chile based on an incomplete specimen, without most of its elytra, and included figures for the anterior end, 1 cirrigerous parapodium, and tips of 1 notochaetae (tapered), and 1 neurochaetae (unidentate), but no elytra were illustrated. Ceratostyles of antennae and dorsal cirrostyles were shown with a subdistal brown ring but were not subdistally expanded. The median antenna is longer than laterals, its base marks a deep V-shaped depression over prostomium, and the parapodium shows acicular lobes projected, but tips of aciculae were not emergent. The pharynx was indicated as having 9 pairs of marginal papillae, but no details of the jaws were provided.

On the other hand, what has been regarded as E. crassa and E. rhizoicolaHartmann-Schröder, 1962 are the 2 only species described and recorded from shallow water depths in Chile. The latter species was also described from Punta Arenas, with a 21 mm long specimen. These 2 species are very similar by having anterior eyes displaced anteriorly, similar types of noto- and neurochaetae, and dorsal cirri with black bands. They differ because in E. crassa the dorsal cirri have a single subdistal black band, against 2 in E. rhizoicola, and its tip is short, whereas it is longer in E. rhizoicola. The main difference is in the presence of fimbriae; there are no fimbriae in E. crassa , whereas E. rhizoicola has some short filaments along posterior margins. It is likely that E. rhizoicola is another junior synonym of H. magalhaensi because it resembles H. longicirratus in having longer dorsal cirri, but this might be a size dependent feature, becoming relatively shorter in larger specimens. Further, H. magalhaensi has been found living in Macrocystis rhizoids (Pratt, 1901), which was the habitat also for E. rhizoicola.

We think that the main reason for the confusion regarding the affinities between what was described as L. crassa and H. magalhaensi is because there were only 1 set of illustrations of the species (Kinberg, 1858), and since during many years, the proposals for new records or new species did not include the study of type or topotype specimens (Fauchald, 1989).

Distribution. Originally described from Puntarenas, Chile, in shallow depths (0-200 m), it ranges along subantarctic localities including the Falkland and Kerguelen Islands.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)