Introduction

The COVID-19 (coronavirus 2 disease) pandemic has established itself worldwide as the most significant public health challenge of the last 100 years. Although the first reports were made in adult populations, the novel SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) also affects the pediatric population, including newborns1-3.

Although children with COVID-19 generally do not present with severe symptoms, and up to 90% may be asymptomatic3-6, it is essential to investigate the behavior of the disease in this population. Based on available data, the pediatric population could play a key role in transmitting the virus, mainly due to its prolonged presence in nasal secretions and feces, which may facilitate its community dissemination in daycare centers, schools, and homes3,7,8.

No information was found on the epidemiological characteristics of patients < 18 years of age with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in Jalisco nor data on the distribution by geographic region or monthly behavior during the pandemic. Therefore, the present study aimed to analyze the spatiotemporal behavior in pediatric patients with COVID-19 in Jalisco, Mexico.

Methods

Study design, source of information, and study period

We conducted a descriptive cross-sectional study from March 1 to September 27, 2020. Data on subjects with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection registered in the state of Jalisco, Mexico, were obtained from the official website of the Ministry of Health, Jalisco, through the Sistema RADAR Jalisco (Jalisco RADAR System) platform, which is an active epidemiological system for COVID-19 detection implemented by the state government in conjunction with the University of Guadalajara. Incidence rates were calculated per 100,000 inhabitants according to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI for its Spanish acronym) latest census9.

Selection criteria

We included individuals ≤ 18 years of age, residents of Jalisco, who met the definition of a confirmed case of SARS-CoV-2 infection. A confirmed case was established as a subject of any age who 7 days prior had presented at least two of the following signs or symptoms: cough, fever, headache (in children < 5 years of age, irritability instead); and at least one of the following signs or symptoms: respiratory distress, arthralgia, muscle pain, odynophagia, rhinorrhea, conjunctivitis, chest pain. Also, a positive result in the real-time retrotranscription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2, performed in the National Network of Public Health Laboratories, which are recognized by the Institute of Epidemiological Diagnosis and Reference (InDRE for its Spanish acronym)10-12.

Study variables and definitions

HEALTH STATUS

Patient health status was divided into ambulatory (outpatient) and hospitalized (inpatient) when the confirmed case was captured.

SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION

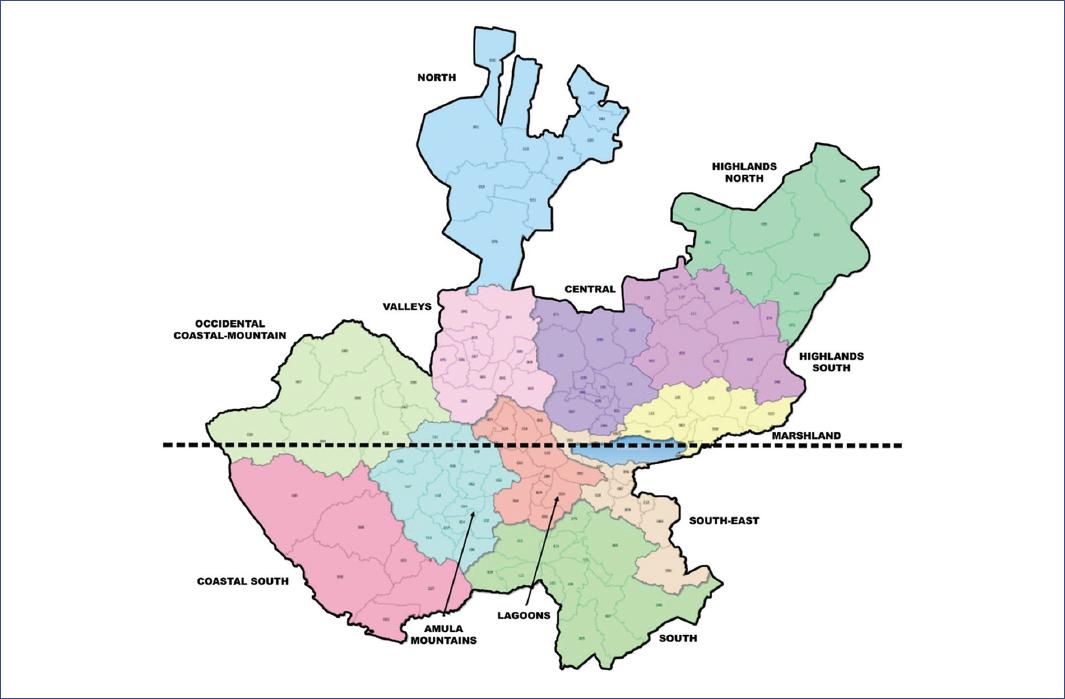

The distribution of cases in the 12 geographic regions that make up the state of Jalisco: North, Highlands North, Highlands South, Marshland, Southeast, South, Amula Mountains, Coastal South, Occidental Coastal-Mountain, Valleys, Lagoons, and Central, including 125 municipalities.

Statistical analysis

Data capture and processing were performed using Microsoft Office Excel® software 2013 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) IBM®SPSS Statistics for Windows v22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the type of distribution of the groups analyzed. Descriptive statistics were used to determine averages and percentages according to every statistical variable. The χ2 test was used to compare qualitative variables, and the Student’s t-test was used for the quantitative variables. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Temporary milestones and control measures

The first case of COVID-19 in Mexico was detected on February 27, 2020, in Mexico City. On February 28, two additional cases were confirmed, resulting in the declaration of COVID Phase 1; that is, the scenario in which the cases were imported from abroad, and there was no local contagion or spread. On March 11, the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 pandemic. On March 14, 2020, the Ministry of Public Education (Secretaría de Educación, Mexico) changed the Easter vacations and extended them to one month (from March 23 to April 20) for all educational institutions nationwide13.

Following the first local infections, the federal government declared Phase 2 on March 24. Some economic activities were suspended; large gatherings were restricted, and it was recommended to stay at home, especially for individuals > 60 years. As of March 26, all non-essential federal government activities were suspended, except those related to security, health, energy, and sanitation. Sneezing into the elbow was recommended, along with frequent hand washing and continuous cleaning and disinfecting of high-use public areas. Persons with symptoms and confirmation of COVID-19 should wear facial masks13.

Due to the evolution of confirmed cases and deaths, a national public health emergency was declared on March 30. The immediate suspension of all non-essential activities in all economic sectors of the country was proclaimed for one month (until April 30). Subsequently, due to evidence of active outbreaks and spread of the virus with more than 1000 cases, phase 3 was initiated on April 21, 2020, which brought with it measures such as the suspension of non-essential activities in the public, private, and social sectors, and the extension of the National Safe Healthy Distance Guidelines until May 3013,14.

Ethical aspects

The local Research and Ethics Committee approved the present study (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social registration number CLIS R-2020-1302-031). The study was conducted based on the Ethical Standards and Guidelines for Research Involving Human Beings established by the Declaration of Helsinki (Fortaleza, Brazil, 2013). Following good clinical practice, the confidentiality of the participants was protected: at no time were they identified by name, and they were assigned a code to protect their anonymity.

Results

From March 1 to September 27, 2020, 58,231 positive cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection were detected in Jalisco. Among them, the pediatric population corresponded to 1,515 patients (prevalence of 3%): the mean age was 12 ± 5 years (range 0-18 years), with a predominance of males (n = 768; 51%), and a higher prevalence of ambulatory patients (n = 1,427; 94%). When comparing the epidemiological characteristics and health status of the pediatric population with the adult population, we found a statistically significant difference in age (12 vs. 43 years, p = 0.001, Student t-test) and in the percentage of hospitalizations (6% vs. 14%, p = 0.001, χ2 test).

According to age distribution in individuals ≤ 18 years, we found that SARS-CoV-2 infection predominated in adolescents aged 15 to 18 years (n = 738; 49%). The prevalence gradually decreased the younger the age of the patients, so that the least affected group was infants < 1 year of age (n = 48; 3%). In this group, we found a slight predominance of the males with a male-female ratio of 1.28:1. This ratio decreased in the older age groups since both sexes were affected almost equally in the 15 to 18 years group, with a male-female ratio of 0.96:1. The percentage of ambulatory to hospitalized patients was lower in the < 1 year of age group than the 15-18 years of age group (1.4:1 vs. 45.12:1) (Table 1).

Table 1 Epidemiological characteristics of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Jalisco distributed by age (n = 58,231)

| Variable | < 1 year (n = 48) | 1-4 years (n = 156) | 5-9 years (n = 205) | 10-14 years n = 368) | 15-18 years (n = 738) | > 18 years (n = 56,716) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male, n (%) | 27 (56) | 89 (57) | 112 (55) | 178 (48) | 362 (49) | 28,923 (51) |

| Female, n (%) | 21 (44) | 67 (43) | 93 (45) | 190 (51) | 376 (51) | 27,793 (49) |

| Ratio M:F | 1.28:1 | 1.32:1 | 1.20:1 | 0.93:1 | 0.96:1 | 1.04:1 |

| Age in years | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | — | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 6.9 ± 1.4 | 12.4 ± 1.3 | 16.8 ± 1.1 | 43 ± 15 |

| Health status | ||||||

| Ambulatory, n (%) | 28 (58.3) | 140 (89.7) | 188 (91.7) | 349 (94.8) | 722 (97.8) | 48,864 (86) |

| Hospitalized, n (%) | 20 (41.6) | 16 (10.2) | 17 (8.2) | 19 (5.1) | 16 (2.1) | 7,852 (14) |

| Ratio A:H | 1.4:1 | 8.75:1 | 11.05:1 | 18.36:1 | 45.12:1 | 6.22:1 |

A, ambulatory; F, female; H, hospitalized; M, male; SD, standard deviation.

The spatial distribution of pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2 (n = 1,434; 95%) was concentrated in five geographic regions: Central (n = 1,257; 83%), Occidental Coastal-Mountain (n = 58; 4%), Highlands South (n = 50; 3%), Highlands North (n = 37; 2.4%), and Marshland (n = 32; 2.1%); the Coastal South region recorded no cases. This spatial distribution by geographic area was similar to that observed in the > 18 years age group, where four of the five regions had a higher number of cases (n = 51,350; 91%) (Table 2). When evaluating the location of the five geographic regions with the most pediatric patients, we found that they were predominately located in the northern part of Jalisco. The Northern region, which is not among the areas with the highest frequency of cases, ranked third in incidence rate, with 148 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, and is located in the northern part of Jalisco (Figure 1).

Table 2 Spatial distribution by geographical region of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Jalisco (n = 58,231)

| Number | Region | ≤ 18 years (n = 1,515) | > 18 years (n = 56,716) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Incidence rate* | n (%) | Incidence rate* | ||

| 1 | North | 12 (1) | 148 | 157 (0.2) | 1,930 |

| 2 | Highlands North | 37 (2.4) | 89 | 958 (2) | 2,293 |

| 3 | Highlands South | 50 (3) | 122 | 915 (2) | 2,224 |

| 4 | Marshland | 32 (2.1) | 94 | 1,265 (2) | 3,731 |

| 5 | Southeast | 9 (0.5) | 77 | 288 (0.5) | 2,469 |

| 6 | South | 30 (2) | 81 | 1,753 (3) | 4,715 |

| 7 | Amula Mountains | 9 (0.5) | 90 | 498 (0.8) | 5,003 |

| 8 | Coastal South | 0 (0) | 0 | 317 (0.5) | 1,775 |

| 9 | Occidental Coastal-Mountain | 58 (4) | 942 | 3,049 (5) | 49,502 |

| 10 | Valleys | 13 (1) | 34 | 909 (2) | 2,365 |

| 11 | Lagoons | 8 (0.5) | 14 | 529 (1) | 955 |

| 12 | Central | 1,257 (83) | 236 | 46,078 (81) | 8,647 |

*Incidence rate per 100,000 inhabitants.

In the < 18 years age group, four of the five geographic regions with the highest number of cases corresponded to those with the highest incidence rates: Occidental Coastal-Mountain, Central, Highlands South, and Marshland. Similarly, in the > 18 years age group, four regions with the highest frequency of cases also had the highest incidence rates: Occidental Coastal-Mountain, Central, Marshland, and South.

Figure 1 The Central, Occidental Coastal-Mountain, Highlands North, and Marshland regions (top half of the map) are among the top five locations with the highest cases in both age groups.

The greatest number of cases was concentrated in the central region, both in the pediatric (n = 1,257; 83%) and adult (n = 46,078; 81%) populations. This region had the second-highest incidence rate in the entire state: 236 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in the pediatric population and 8,647 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in the adult population; it ranked only behind the Occidental Coastal-Mountain region where incidence rates were 942 cases per 100,000 inhabitants and 49,502 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively (Table 2). Of the 12 municipalities that comprise the Central region, the five with the highest numbers of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 were Guadalajara, Zapopan, Tlaquepaque, Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, and Tonalá, where we detected 1,224 (81%) patients ≤ 18 years of age and 44,774 (79%) > 18 years (Table 3). Other municipalities with a high number of pediatric cases were Puerto Vallarta, with 53 cases (3%) and 18 cases per 100,000 inhabitants; Tepatitlán, with 30 cases (2%) and 20 cases per 100,000 inhabitants; and San Juan de los Lagos, with 18 cases (1%) and 25 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.

Table 3 Five municipalities with highest numbers of cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Jalisco distributed by age groups (n = 58,231)

| Region | ≤ 18 years (n = 1,515) | > 18 years (n = 56,716) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Incidence rate* | n (%) | Incidence rate* | |

| Guadalajara | 486 (32) | 35 | 20,851 (37) | 1,505 |

| Zapopan | 453 (30) | 31 | 13,225 (23) | 896 |

| Tlaquepaque | 112 (7) | 16 | 4,300 (7.5) | 626 |

| Tlajomulco de Zúñiga | 100 (7) | 14 | 3,267 (6) | 449 |

| Tonalá | 73 (5) | 13 | 3,131 (5.5) | 549 |

*Incidence rate per 100,000 inhabitants.

When addressing the temporal distribution of pediatric patients with COVID-19 in these five municipalities, we observed an increase in the number of cases starting in the second two-month period of the study since 17 cases were detected between March-April. In contrast, the number increased to 311 in May-June. Finally, in the last quarter of the study period, 896 cases were identified; the highest number of cases occurred in August (353 patients) (Table 4).

Table 4 Temporal behavior of the numbers of cases ≤ 18 years of age with SARS-CoV-2 infection in the five most affected municipalities in Jalisco (n = 1,224)

| Municipality | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guadalajara | 3 | 8 | 44 | 100 | 113 | 133 | 85 | 486 |

| Zapopan | 0 | 1 | 26 | 65 | 114 | 149 | 98 | 453 |

| Tlaquepaque | 1 | 1 | 16 | 14 | 40 | 24 | 16 | 112 |

| Tlajomulco | 0 | 0 | 12 | 17 | 31 | 29 | 11 | 100 |

| Tonalá | 1 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 73 |

| Total | 5 | 12 | 107 | 204 | 316 | 353 | 227 | 1,224 |

When evaluating the temporal distribution of pediatric cases according to the health measures adopted by the state government, we observed that social isolation and the suspension of in-person classes decreased the number of cases from seven to two and that the closure of non-essential commercial centers and the mandatory use of facial masks allowed a slight increase of only 19 patients in one month. In contrast, with the decrease in the strictness of these measures due to festivities or holidays, the number of cases increased exponentially: in May, after the Labor Day long weekend, the number of patients increased to 161 (eight times more than those recorded the previous month); in June, the opening of beaches, hot springs, water parks, and zoos was associated with an increase of 539 cases in the 50 days (Table 5).

Table 5 Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection distributed according to measures adopted by the government of the state of Jalisco (n = 58,231)

| Period | Actions | ≤ 18 years (n = 1,515) | > 18 years (n = 56,716) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01/03 to 13/03 | Day zero Before the onset of measures |

7 | 217 |

| 14/03 to 01/04 | March 13 Social isolation |

2 | 121 |

| March 17 Suspension of in-person classes | |||

| 2/04 to 20/04 | April 01 Closure of non-essential commercial centers |

9 | 390 |

| 21/04 to 01/05 | April 20 Obligatory use of facial masks |

10 | 359 |

| 2/05 to 31/05 | May 03 Preventive measures are decreased (long-weekend?) |

161* | 4,011** |

| 1/06 to 11/06 | June 01 Opening of non-essential businesses at 50% capacity |

87 | 4,066 |

| 12/06 to 15/06 | June 11 Declaration of Individual Responsibility |

27 | 1,439 |

| 16/06 to 20/07 | June 15 Opening of beaches |

353*** | 15,441*** |

| 21/07 to 04/08 | July 20 Opening of hot springs, water parks, zoos |

186*** | 7,683*** |

| 05/08 to 27/09 | August 06 Open cinemas and casinos |

673 | 22,989 |

*In individuals ≤ 18 years, there were 55 cases from May 2-14 and 106 from May 15-31 (14 days after the May long weekend).

**In individuals > 18 years, there were 915 cases from May 2-14 and 3,096 from May 15-31.

***The opening of beaches, hot springs, water parks, and zoos brought about 539 new cases in individuals ≤ 18 years and 23,124 new cases in those > 18 years of age.

Discussion

Research related to the epidemiological behavior of SARS-CoV-2, especially in pediatric age groups, is scarce. In our study, the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents was 3%, similar to the 3.9% reported by the Dirección de Información Epidemiológica in subjects under 20 years of age nationwide15, but higher than that reported in China—with 2% of positive cases in individuals under 19 years of age—and Italy with 1.2%3,4. However, these rates could be higher, as asymptomatic infections are known to occur in the pediatric population. In China, for example, up to 13% of virologically confirmed cases are considered to have an asymptomatic infection; that is, many children without symptoms are not evaluated4.

Regarding age at presentation, we found a mean age of 12 years. In contrast, Dong et al. found a mean age of 7 years4. Other countries also report lower mean ages than the pediatric population of Jalisco: 6 years in India, 7 years in Morocco, and 8 years in the United States16-18. While in these other countries, school-age children predominate, we found in our population that almost half of the subjects were adolescents (15-18 years of age) with a prevalence of 49%. This difference could be explained because we included ambulatory and hospitalized patients, whereas the approach in other countries considered only patients requiring hospitalization. In our study, 94% of the pediatric population was ambulatory.

Furthermore, we found a slight predominance of males (51% of cases), a lower prevalence than that reported in the pediatric population in China (56.6% males) and Mexico City (59% males). However, in both studies, the difference regarding sex was not significant4,19.

Regarding the health status of the subjects included in the present study, we found 16.2 ambulatory patients for every hospitalized one patient in the group ≤ 18 years of age, whereas this ratio diminished to 6.2 ambulatory patients for every hospitalized one patient in the group >18 years, which was a statistically significant difference. This finding supports what has already been observed: the pediatric population presents less severe clinical conditions that allow ambulatory treatment3, while the prognosis is worse in the adult population, partly due to comorbidities that make them more susceptible to developing complications and being hospitalized20.

The ratio of pediatric ambulatory patients to hospitalized patients varied among age groups. We found that most hospitalizations occurred in the < 1-year-old group, where for every 1.4 ambulatory individuals, one was hospitalized (almost a 1:1 ratio). Conversely, this ratio increased proportionally with age, so that in the 15-18 years-old group, there were 45.1 ambulatory patients for every hospitalized one.

Regarding spatial distribution, it was interesting to note that four of the five geographic regions with the highest number of cases (Central, Occidental Coastal-Mountain, Highlands North, and Marshland) are located in northern Jalisco. We do not know whether environmental conditions in these areas, such as air pollution, environmental degradation, climate, or temperature factors, may facilitate infection or modify virus survival, as mentioned in a previous publication21. In any case, this finding could be the basis for future research.

When analyzing the number of individuals with COVID-19 by geographic region, we found that most of the confirmed cases were concentrated in the Central area: 83% of patients in the pediatric population and 81% in the adult population. This is an expected finding if we consider that the Central region includes the municipalities of Guadalajara, Zapopan, Tlaquepaque, Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, and Tonalá where 81% of our pediatric patients were concentrated. These high percentages could be attributed to the higher population density than other municipalities in the state. According to the latest INEGI9 census, Guadalajara has 10,361 inhabitants/km2, while the mean population density for the state is 100 inhabitants/km2. Therefore, the higher the population density, the greater transmissibility of the virus.

The Occidental Coastal-Mountain (4%) and Highlands South (3%) regions followed the Central area in positive cases in the pediatric population. Although they do not have the population density of the Guadalajara metropolitan area, these regions include the municipalities of Puerto Vallarta, Tepatitlán de Morelos, and San Juan de los Lagos. These municipalities have a high urban concentration during part of the year due to recreational, commercial, and religious tourism22.

As expected, the number of cases increased exponentially at the onset of the community spread phase regarding the temporal distribution of cases. However, we should emphasize that the infection peaks were related to reducing sanitation measures to prevent it23. For example, between May 2 and May 14, 55 cases were confirmed in ≤ 18 years, and 915 in > 18 years; however, between May 15 and May 31, 14 days after the Labor Day holiday (May 1), rates rose to 106 cases (almost double) in < 18 years, while they tripled in those >18 years of age with 3,096 patients.

Similarly, on June 1, non-essential commercial activities returned to 50% of their standard capacity in the state of Jalisco23. Unfortunately, this opening resulted in the reporting of 5,619 new cases in the first 15 days of the month alone, when the total number of positive cases reported in March, April, and May were 5,287. Although this increase was mainly at the expense of the adult population, pediatric patients were not exempt since, in those 15 days, 114 new cases were registered; that is, 60.3% more than previously recorded in this population.

Finally, in July, following the reopening of recreational aereas23 such as beaches, hot springs, water parks, and zoos, 539 cases were recorded in <18-year-old and 23,124 in those >18 years; while in August, with the opening of cinema theatres and casinos23, the highest rates observed in our study were registered, with 673 new cases in the pediatric population and 22,989 in adults.

Due to the nature of the database contained in the Sistema RADAR Jalisco platform, this study has several limitations: the clinical presentation of the disease is unknown; the patients included belong to an anonymous database, so neither their treatments nor their results were available; there is no follow-up of the individuals included, so the clinical evolution, vital status, prognosis, and variables that may affect them are unknown; finally, the information is from a single state, so the results cannot be generalized to the rest of the country. Despite these limitations, our series is more extensive than that reported for the state of Sinaloa (51 patients)24 and for Mexico City (510 patients)19, which allows us to contribute essential data of interest that have not been published previously, and that can guide us on the epidemiological and spatiotemporal behavior of pediatric patients with COVID-19 in the state of Jalisco.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)